Abstract

Background

Voluntary medical male circumcision (MC) is safe and effective. Nevertheless, MC programs require multiple post-operative visits. In Zimbabwe, a randomized control trial (RCT) found that post-operative two-way texting (2wT) between clients and MC providers instead of in-person reviews reduced provider workload and safeguarded patient safety. A critical component of the RCT assessed usability and acceptability of 2wT among providers and clients. These findings inform scale-up of the 2wT approach to post-operative follow-up.

Methods

The RCT assigned 362 adult MC clients with cell phones into 2wT; these men responded to 13 automated daily texts supported by interactive texting or in-person follow-up, when needed. A subset of 100 texting clients filled a self-administered usability survey on day 14. 2wT acceptability was ascertained via 2wT response rates. Among 2wT providers, eight key informant interviews focused on 2wT acceptability and usability. Influences of wage and age on response rates and client-reported potential AEs were explored using linear and logistic regression models, respectively.

Results

Clients felt confident, comfortable, satisfied, and well-supported with 2wT-based follow-up; few noted texting challenges or concerns about healing. Clients felt 2wT saved them time and money. Response rates (92%) suggested 2wT acceptability. Both clients and providers felt 2wT was highly usable. Providers noted 2wT saved them time, empowered clients to engage in their healing, and closed gaps in MC service quality. For scale, providers reinforced good post-operative counseling on AEs and texting instructions. Wage and age did not influence text response rates or potential AE texts.

Conclusion

Results strongly suggest that 2wT is highly usable and acceptable for providers and patients. Men with concerns solicited provider guidance and reassurance offered via text. Providers noted that men engaged proactively in their healing. 2wT between providers and patients should be expanded for MC and considered for other short-term care contexts.

The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, trial NCT03119337, and was activated on April 18, 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03119337

Introduction

Voluntary medical male circumcision (MC) is a critical HIV prevention intervention with global support for expansion across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1–8]. Over 22 million MCs were performed across 14 sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries between 2008–2018 [9]. MC is cost-effective for HIV prevention [10–13] making investment in MC a priority across SSA [12, 14–17]. However, severe health system constraints threaten the quality and pace of MC scale-up [18–20], reducing the likelihood of meeting the ambitious global target of 5 million annual MCs in SSA [21]. Failure to reach MC targets means fewer infections averted [22, 23]. In addition, PEPFAR and UNAIDS identify scarcity of resources as a major risk factor threatening further control of the HIV epidemic [24]. New, cost-effective innovations that improve efficiency while maintaining or improving MC quality are crucial to attain HIV prevention milestones and safeguard scarce HIV epidemic control resources [25].

MC is safe and major complications are rare; thus, most follow-up visits are unnecessary [26, 27]. Adverse events (AEs) from gold-standard active surveillance [25, 28, 29] report 5–7% AEs [4, 30–32] while routine passive surveillance reports below the commonly-accepted 2% AE rate [33–37]. To ensure client safety, current global standards for high quality MC services nevertheless require at least one follow-up within 14 days [38, 39]. Post-operative guidelines in many countries, including those in Zimbabwe[40], strongly suggest three post-operative visits. However, with low AE rates, overstretched clinic staff likely waste invaluable resources conducting reviews for MC clients without complications. For clients, men healing well needlessly pay for transport, miss work, and wait for reviews. Innovations that safely target MC follow-up only for men with potential AEs would vastly reduce unnecessary visits, safeguarding critical resources for optimizing quality MC service delivery.

As a national MC implementing partner, the ZAZIC consortium, led by the University of Washington’s International Training and Education Center for Health (I-TECH) and local implementing partners, The University of Zimbabwe (UZ), Zimbabwe Association of Church-related Hospitals (ZACH), and Zimbabwe Community Health Intervention Research Project (ZiCHIRe), works in partnership with the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) to implement MC services in 13 districts [41]. Ensuring follow-up visit attendance, a routine MC program indicator, stretches scarce ZAZIC resources in an environment of few AEs: AE rates within both National and ZAZIC MC programs are less than 0.3% [33, 40]. Therefore, we implemented a randomized control trial (RCT) in two peri-urban clinics in Zimbabwe to test two-way texting (2wT) between patients and providers, allowing men healing without complication to opt-out of their routine post-operative visits. RCT design details are available [42]. Clinical results from the RCT, published previously, identified AEs among 1.88% of 2wT arm participants and 0.84% of control arm men, suggesting that 2wT could safely reduce MC follow-up visits, reduce provider workload, and serve as a proxy for active surveillance [27].

In this mixed-methods study, we aimed to explore 2wT usability and acceptability among 2wT patients and healthcare providers focusing on understanding how providers and patients interacted with the 2wT system and obtaining insights into the obstacles and facilitators of system use. High usability and acceptability of 2wT is crucial for this technology to successfully expand across Zimbabwe and the region. Usability has been defined as the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to complete a task effectively, efficiently and with satisfaction in a specified setting [43–45]. More recent usability definitions also include concepts such as learnability, encouragement for use, minimizing errors, accessible to a wide range of individuals, and easy to maintain [46, 47]. Although usability may be applied differently across contexts, for the purposes of this paper, we focus on the perceived quality of the user experience interacting with the 2wT system [48], considering both client and provider input. For acceptability, we focused on the usefulness of the system and user perceptions of the importance of system functions. In contrast with usability, acceptance should not be reported by users, but should be demonstrated via evidence that users employ the technology for the intended purposes [49, 50]. Therefore, as evidence of acceptability, we explored client interactions with the system and their perceptions of its usefulness as an alternative to in-person follow-up care.

Evidence of high usability and acceptability is consequential for MC programs in Zimbabwe and elsewhere that are considering 2wT interventions to support follow-up. If the hybrid approach to integrating computer-automated messaging with human-to-human 2wT proved highly usable and acceptable, this digital health intervention could be applied to improve care and reduce provider workload in other follow-up care contexts. We hypothesized that 2wT acceptability and usability would be high, aiding program scalability and replicability.

Theory of change

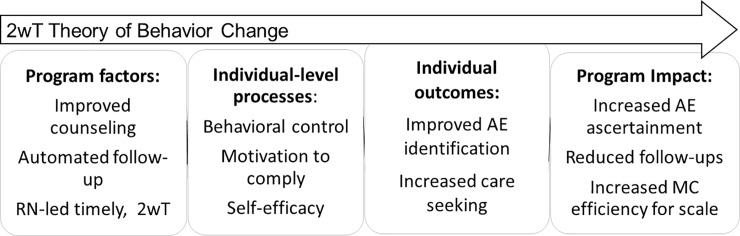

Ensuring 2wT usability and acceptability was critical to facilitating success from both provider and patient perspectives. Fig 1 maps how the 2wT intervention (program) aimed to influence individual factors (processes) in support of positive behavior change (individual outcomes) among male clients. 2wT targeted key individual-level constructs proven effective in previous HIV-related behavior change programs [51, 52]. First, 2wT providers enhanced post-operative counseling, encouraging self-efficacy to identify healthy healing [53] and control over the decision to return for in-person care if desired [54]. Then, via subsequent hybrid 2wT, providers connected with, and identified, men with potential AEs in need of provider triage and/or follow-up. These daily texts and swift individualized responses aimed to reinforce client motivation to respond [55]. Using theory to drive our intended effects, 2wT sought to empower men to correctly ascertain their healing progress and encouraged timely care seeking. We considered client engagement with the system as an indicator of usability and acceptability.

Fig 1. 2wT theory of change.

2wT theory of program (intervention) change.

2wT technology overview

The 2wT system, the backbone of the intervention, was built using the Community Health Toolkit (CHT), an open source project which supports over 25,000 health workers across dozens of digital health activities. Apps built using the CHT work with or without internet connectivity, in any language, on basic phones, smartphones, tablets, and computers [56]. Since 2010 the CHT’s core framework was shaped by a rigorous and well documented human-centered design process [57]} and is highly configurable. The overall CHT (https://communityhealthtoolkit.org/) supports the vast majority of the critical needs outlined by the WHO Classification of Digital Interventions [58]. Specifically, the 2wT system provides a model of four core WHO-promoted interventions at the patient and provider levels: 1) automated and patient-to-provider interactive messaging; 2) SMS-based triaging of clients by nurses (e.g. for referrals to care); 3) daily client monitoring via SMS; and 4) longitudinal patient records (potential AEs, AE follow up, referral confirmation) and reporting (e.g. client response rates). The 2wT features were designed to support a streamlined workflow and high quality MC services while generating data to monitor program delivery. The usability and acceptability of systems built using the CHT cannot be taken for granted; it is important that they be tested for specified purposes, with specified users, in particular use contexts.

Methods

2wT intervention

Before full study implementation, message content was pre-tested for clarity of content and understandability in both Shona and English. Texts were reduced to 140 characters to ensure complete message content on multiple phone types and cell services. A pilot of 50 men assigned to texting intervention informed in-box modifications, SMS formatting, and message delivery optimizations (timing, frequency, language preferences). Pilot experience also identified wi-fi access via an internet dongle as the most resilient to fluctuations in electricity and cell networks. Automated messages were sent daily at 8am.

Implementation details of the prospective, un-blinded RCT study were described previously [27, 42]. In brief, ZAZIC follows all MoHCC protocols based on WHO guidelines including routine surgical MC follow-up on post-surgery days 2, 7 and 42 and adverse event (AE) management [59]. All MC care was provided free to clients from MoHCC. All men in the study (both 2wT and control arms) received all routine MC surgical care and both pre- and post-operative counseling at one of two public clinics: Seke South (peri-urban) or Norton (rural). However, in lieu of routine, in-person, post-operative visits, the 2wT clients received automated daily texts from days 1–13 and were asked to respond about their healing. Study texts are shown in Table 1. Daily responses were simple: only a single-digit response was required if the man believed he was healing well (“push ‘0’ and hit send”), and no further action was taken. If a 2wT MC client responded with suspicion of an AE (“push ‘1’ and hit send”), an MC nurse interacted with the client via SMS or phone, as requested. Clients chose the language of the automated texts at enrollment (English or Shona) but could engage the nurse in text communication using a mix of languages or common texting abbreviations. Clients were asked to return to the clinic if referred or desired. Follow-up communication at any time could be initiated by a client or the nurse. Participants in both arms were asked to return to the clinic on Day 14 for a study-specific review. No incentive was provided to study participants at enrollment. In recognition that sending texts in Zimbabwe costs approximately $0.05 [60], all study participants received a $5 phone card on Day 14 in appreciation for their participation.

Table 1. 2wT scripted message content.

| Text purpose | English | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Day 0 Enrollment Confirmation | Thank you for participating in this study. | Auto |

| 8am: Days 1,3,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13 | How are you? Are you experiencing any bleeding, swelling, pus, pain, redness or wound opening? Enter 1 = Yes, 0 = No and press send | Auto |

| 8am: Day 2 | It is Day 2. Remove the bandage. Any bleeding, swelling, pus, pain, redness or wound opening? Enter 1 = Yes, 0 = No and press send | Auto |

| If Client SMS “1” to the above | Which symptoms? Bleeding, swelling, pus, pain, redness, wound opening, or something else? | Manual |

| If they say they have a suspected AE | Please return to the clinic. If you would like a healthcare provider to call you, beep us. Otherwise, text us your question here | Manual |

| If they stop responding to SMS | Please seek VMMC follow-up care at the clinic | Manual |

| 8am: Day 7 | It is Day 7. Are you experiencing any bleeding, selling, pus, pain, redness or wound opening? Enter 1 = Yes, 0 = No and press send | Auto |

| 8am: Day 13, msg 1 | Thank you for participating in the study. Please return to the clinic tomorrow for your short Day 14 visit and to receive your airtime | Auto |

| 8:02am: Day 13, msg 2 | How are you? Are you experiencing any bleeding, swelling, pus, pain, redness or wound opening? Enter 1 = Yes, 0 = No and press send | Auto |

| Day 14 | Thank you for participating. Today is Day 14. Please return to clinic today for review and to receive airtime. | Auto |

Quantitative methods

Of the 721 men in the RCT, 362 men were assigned to texting and included in this analysis. On day 14, a self-administered questionnaire was implemented with a subset of 100 of the 362 2wT MC clients (28%) to gauge satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and ascertain suggestions for intervention improvement. Responses of these 100 men were entered and frequencies explored in Excel for usability results. Data from all 362 are used to assess acceptability and usability as reflected in the system response rates and how the system was employed by the clients. Age and wage have plausible, a-priori relationships with usability and acceptability. Therefore, to determine whether the intervention was equally beneficial to all men, we explored the relationships between age and daily wage on both the number of text responses and potential AE texts among all 362 2wT texting arm men. The outcome variable, number of text responses, was a continuous measure of the number of daily texts to which a client responded, ranging from 0–13. The outcome variable, potential AE text, was a dichotomous variable defined as a client sending one or more potential adverse event responses to the daily text versus none. Both age and wage were categorized into quartiles. For daily wage, groups were: $0; 0-$5; $5-$15; and $16+. For age in years, categories were: 18–20; 21–24; 25–29; and 30 and above. We used linear regression for total text responses and logistic regression for potential AE text responses. Robust standard errors were used for all models. Coefficients and odds ratios (OR) were presented for linear and logistic regression models, respectively. Multivariate models included both wage and age variables. STATA 15.1.0 (StataCorps, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis.

Qualitative methods

We conducted brief (about 20 minutes) key informant interviews (KIIs) with eight clinicians involved in MC service delivery and 2wT-based follow-up to gauge acceptability; satisfaction; identify facilitators and barriers to program success; and ascertain suggestions for intervention improvement. Interviews were conducted at both 2wT intervention clinics: five interviews at Seke South and four at Norton. KIIs were audio recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis [61] was employed, guided by a process of open coding based on anticipated responses suggested by the KII guide. Atlas.Ti software was used to create a spreadsheet of key themes, perceived barriers, and suggested facilitators to the program from KIIs. Usability questionnaires from the subset of 100 2wT texting men also contained several open-ended questions to ascertain perceptions of system use; those results were aggregated and grouped into themes using Excel.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ) and the University of Washington, Seattle, USA, Internal Review Board. All subjects, clients and healthcare workers, received comprehensive information regarding their voluntary participation in the study and signed a written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Results

Quantitative

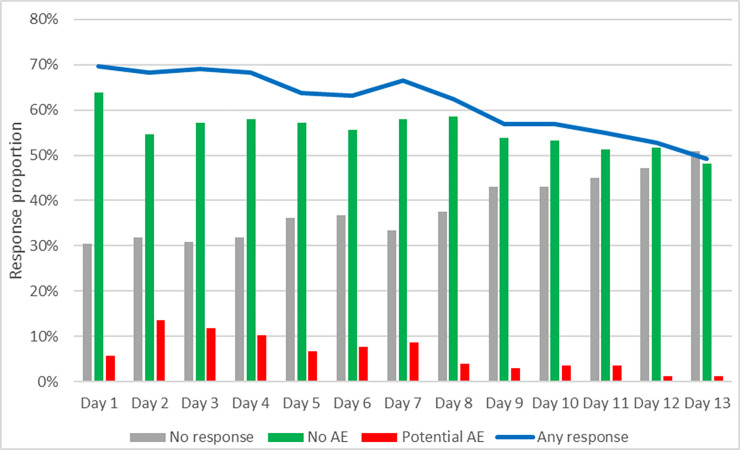

Study enrollment occurred from June 18, 2018 to February 11, 2019; follow-up ended March 13, 2019. RCT enrollment, assignment, follow-up, and analysis of clinical outcomes were previously detailed [27]. The RCT enrolled 721 men and randomized them 1:1 to intervention (2wT) and control (routine): 362 (50%) were in the 2wT arm (Table 2) and included in this analysis of usability and acceptability. More than half (57%) of the 362 men responded to their daily text when it arrived at 8am, with 86% of responses within 4 hours. Over 92% responded to at least one daily text, showing high system acceptance. Response rates varied over time: approximately 70% of men responded on Day two while half responded on Day 13. Potential AE responses peaked on Day 2 and diminished thereafter (Fig 2). The nurse had 30 phone interactions with clients: 19 “call me back” requests were responded to and 11 calls were made to the nurse, directly, with a concern. Over the course of the intervention, clients sent over 1200 free text SMS to the 2wT nurse.

Table 2. Characteristics of 2wT arm men.

| Characteristic | 2wT | Full study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 362 (%) | N = 721 | ||

| Age category (years) | |||

| 0–20 | 92 (25.4) | 207 (28.7) | |

| 21–24 | 90 (24.9) | 178 (24.7) | |

| 25–29 | 75 (20.7) | 133 (18.5) | |

| 30+ | 105 (29.0) | 203 (28.2) | |

| Site | |||

| Seke South | 300 (82.9) | 594 (82.4) | |

| Norton | 62 (17.1) | 127 (17.6) | |

| Language selected for 2wT daily message | |||

| English | 154 (42.5) | 281 (39.0) | |

| Shona | 208 (57.5) | 440 (61.0) | |

| Cell company | |||

| Econet | 321 (88.7) | 636 (88.2) | |

| Other | 41 (11.3) | 85 (11.8) | |

| Daily wage category ($USD) | |||

| 0 | 108 (29.8) | 254 (35.5) | |

| >0–5 | 86 (23.8) | 155 (21.7) | |

| >5–15 | 98 (27.1) | 179 (25.0) | |

| >15 | 70 (19.3) | 128 (17.9) | |

Fig 2. Response rates over time, by response type.

Closed-ended client survey responses suggest that most clients felt confident, comfortable, satisfied, and safe with SMS follow-up (Table 3). Few noted challenges with texting or were concerned about their wound healing without in-person review. Clients also felt that 2wT saved them time and money. As compared to alternative texting schedules, men preferred one daily text (76%), and they preferred that the text arrive in the morning (86%).

Table 3. Responses on 2wT acceptability and usability from 2wT clients.

| (N = 100) | Mean Likert score |

|---|---|

| I was clear on when to SMS, call, or return for care | 4.68 |

| I felt safe with the daily SMS | 4.63 |

| I was comfortable with this approach to MC follow-up care | 4.59 |

| I understood the SMS process well | 4.57 |

| I felt prepared to remove my bandages on Day 2 | 4.5 |

| I felt confident that I would get the care I needed at the clinic | 4.31 |

| I felt that I could come to the clinic when I wanted | 4.14 |

| I understood the signs of poor healing | 4.05 |

| I want fewer SMS | 3.05 |

| I wanted more SMS on signs of adverse events | 2.83 |

| I wanted help to remove my bandages on Day 2 | 2.73 |

| I was worried about my wound healing | 2.56 |

| I had challenges sending SMS | 2.33 |

| I had challenges receiving SMS | 1.89 |

| I wanted more in-person follow-up | 2.42 |

| I am worried about my privacy receiving these messages | 2.77 |

| No mandatory follow-up visits saved me money | 4.35 |

| No mandatory follow-up visits saved me time | 4.35 |

| I feel satisfied with the SMS follow-up | 4.61 |

| I would recommend SMS follow-up to my friends | 4.50 |

Both age and wage were associated with increased text response rates among 2wT men in univariate models (Table 4). On average, men from ages 21–24, 25–29, and 30+ sent an SMS on 2 more days than their younger peers, ages 18–20. Men with daily wages of $5-$15 or more than $15 sent an average of 1 or 2 more messages, respectively, over the follow-up period than those without income. In the multivariate model, age remained significantly associated with increased number of daily SMS responses. Although daily wage of $5-$15 compared to no income was associated with an increased likelihood of sending a potential AE message, this relationship was not significant when controlling for age in the multivariate model. Age was not associated with the likelihood of sending a potential AE text.

Table 4. Factors associated with texting response rate and potential AE texts.

| N = 362 | Total SMS responses† Coefficient (95% CI) | Potential AE text†† OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 0–20 | ref | ref | ref | Ref |

| 21–24 | 2.24*** (1.07–3.41) | 2.06*** (0.87–3.25) | 1.64 (0.90–2.98) | 1.63 (0.88–3.01) |

| 25–29 | 1.83** (0.59–3.08) | 1.49* (0.15–2.84) | 1.47 (0.79–2.76) | 1.39 (0.71–2.74) |

| 30+ | 2.38*** (1.25–3.51) | 1.91** (0.56–3.32) | 1.64 (0.92–2.92) | 1.66 (0.85–3.23) |

| Wage ($) | ||||

| 0 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 0–5 | 0.97 (-2.00–2.15) | 0.81 (-0.36–1.98) | 1.54 (0.86–2.74) | 1.48 (0.82–2.68) |

| 5–15 | 1.39* (0.26–2.53) | 0.75 (-0.47–1.98) | 1.84* (1.05–3.22) | 1.56 (0.86–2.89) |

| 15+ | 1.93** (0.71–3.15) | 1.08 (-0.32–2.38) | 1.11 (0.60–2.07) | 0.89 (0.44–1.81) |

*p<0.05

**p<0.01

***p<0.001.

† Results from linear regression.

†† Results from logistic regression.

Qualitative

2wT clients

For the open-ended responses among the 100 men who completed the usability survey on day 14, 45 responded (45%) to the question on formatting improvements; almost all responses suggested no change. Of the 42 men who responded about improved message content, the vast majority also suggested no change. However, addition of the day number (e.g., “this is the day 1 text”) was suggested while a few others noted more information on the terms, e.g., “puss,” should be explained. For the question on how to improve SMS follow-up, most responded that they liked the system as it is, but several noted that they would like to receive a call if they did not respond by text. Two men requested to be given airtime on Day 0. Overall, most men responded similarly to these participants who wrote, “messages reduce time and if there is a problem you are given time to communicate. It's just an efficient way of communicating.” Another client expressed that, “the follow-up process is good because you can do what you want and also can make a monetary saving by not visiting the clinic.”

Healthcare workers

Additional insight from the eight KIIs conducted after the completion of the full study suggested several themes to inform 2wT scale-up. Overall, the healthcare workers felt favorably towards 2wT, as men “don’t like coming for follow-up review visits.” Another KI revealed that, “in VMMC we have challenges with adult clients, they don’t come [back for reviews], the numbers are not as you would want them to be.” As a result, 2wT was welcomed by the HCWs, one of whom stated:

We are looking forward to positive results that will lessen the burden on the service provider and improve post-operative quality care on the circumcised client and avoid any AE because of the on-going communication and feedback coming from the client.

The KIs believed that 2wT reduced their overall workload. During the study, they “only did a few reviews since clients were reviewed via cellphones.” Scaling up 2wT with fewer post-operative reviews could lead to “reducing burnout on health care workers. If you don’t go for reviews it means you have enough time for other duties at the clinic.” Several clinicians echoed the opinion that that 2wT could “reduce the demand for staff to be going out and cut on costs for going to the field looking for clients when doing reviews."

KIs felt the 2wT intervention made the men partners in their healing process and “gave the patients responsibility to cater for their health.” It also gave the clinicians more confidence in their patients and “actually helped us realise that men are actually more capable of taking care of themselves.” Another KI noted that the intervention empowered men to be more vigilant in wound care.

“We used to doubt that clients could manage themselves but because of the study we realized that people were responsible for their own health… They were empowered. They become part and parcel of the programme.”

KIs also expressed several advantages specifically for clients. The KIs thought that 2wT would save men money “by reducing transports costs. And also they were not phoning which means they were only using texts which cost only 5 cents.” They also felt that clients saved time, as “most of our clients are self-employed so the time wasted in returning to the clinic was reduced which was positive to the clients as well as to the service provider.” When asked if they were concerned that men would ignore signs of AEs, one KI summed bluntly: “VMMC is a very sensitive area, men are worried about their organs. If they have got a problem they react, so there won’t be any problems that they would ignore and not seek help.”

Lastly, clinicians shared several suggestions for 2wT scale-up. First, clients need clear instructions and post-operative counseling on wound care, bandage removal, and how to text to be able to safely use 2wT. Furthermore, clients needed reminders that 2wT was not for after-hours or emergency care. Several KIs noted potential issues for more rural areas with less reliable cell network or consistent electricity. One KI emphasized the need to maintain active tracing for non-responder, as provided currently for those who do not return to care. Lastly, although few clients noted financial challenges, four KIs suggested providing airtime on Day 1.

Discussion

The results from mixed-method assessment of 2wT usability and acceptability strongly suggest that the hybrid automated/human-to-human SMS system is both acceptable and easy to use, complementing the clinical outcome data that showed 2wT between providers and clients helped ensure healthy wound healing and reduced unnecessary in-person visits [27]. The automated 2wT daily messages reminded clients of the signs of poor healing and encouraged wound observation for the most critical 13 days after MC, the period during which 95% of AEs occur [62]. Clients thought 2wT provided a similar level of reassurance as routine visits, but without the added time or money incurred from an in-person review. Clinicians believed 2wT empowered men to engage in their own healing, assuring them that their clients were capable of identifying potential problems and seeking care when they wished rather than on a mandated schedule. 2wT would not entirely replace clinical care or oversight, but could reduce the burden of unnecessary care on overstretched healthcare workers and reduce client costs while encouraging visits for those who desire or require care. 2wT’s usability and acceptability appears to have helped ensure success. There are several lessons learned for future 2wT within the MC context or other shorter-term follow-up situations that may benefit from this type of direct provider-to-patient SMS.

Although digital health interventions document challenges in retention and adherence [63], 2wT improved upon previous texting interventions in several substantial ways. First, the technology, itself, was designed with usability at the forefront. Although mobile health (mHealth) interventions are growing in popularity [64–70], many short message service (SMS)-based health promotion efforts blast pre-defined messages to many people simultaneously [71–73], removing patients’ ability to communicate back with healthcare workers [74]. By contrast, designing technology to support or augment end user skills and capabilities, as we did by enabling clients to ask questions and initiate care via SMS, is recognized as a central feature of human-centered approaches to system design [57]. Second, two-way texting with a mix of automated and human-to-human messaging optimizes for individualized content, efficiency for staff, and rapid follow up for the fraction of cases with complications, enabling interactive communication between clinicians and patients [75, 76]. Third, the short 13-day 2wT intervention maximizes client adherence, while common barriers such as phone theft, damage, and change of phone numbers [77] are minimized over the brief follow-up period. Fourth, the 2wT MC intervention implemented core characteristics of mHealth excellence, including client accessibility and acceptance; low technology costs, effective local adaptation, strong stakeholder collaboration, and government partnership for sustained impact [78]. Lastly, due to the high proportion of routine MC visits rendered moot when men confirm healing well via SMS, 2wT for MC realizes immediate gains in efficiency, unlike texting for patient education or behavior change.

The familiarity and flexibility of SMS (human-to-human messaging) likely played a role in usability and acceptability. All enrolled clients received their initial text while still in the clinic with MC healthcare providers, providing a personal connection and immediate reassurance that the texting system worked. Post-operative counseling, enhanced with emphasis on expected text responses and the healing process, likely increased client confidence in their ability to recognize and report potential AEs via SMS and act on both information and guidance provided via text. The automated daily text messages also appeared to comfort clients, helping them feel attended to without the need for an in-person visit. Few men requested calls or called the nurse directly, likely suggesting that the men felt that their needs were well met via SMS. For providers, the automated daily SMS significantly reduced the burden on the study nurse as the system, itself, handled the majority of outgoing messages. This enabled the nurse to prioritize time and communication with the clients who suspected an AE or who, for any other reason, initiated a text conversation or requested a call. By reducing the burden on the nurse, and removing the need for further communication with clients who responded with “No AE,” she was able to respond to many more clients than she would have been able to manage in person at the clinic.

This intervention increased male engagement in care, a recognized need in HIV programs. Despite the fact that men’s uptake of healthcare services is lower than that of women [79], interventions that increase male involvement in HIV-related care are absent in much of SSA. Men are less likely to enter the HIV care cascade [80, 81], especially in rural areas [82], threatening HIV prevention efforts. mHealth interventions, like 2wT, show progress in increasing male engagement with care[83, 84]. 2wT appeared acceptable, feasible, and empowering for male clients [85], successfully garnering active participation from men in post-MC healing. 2wT in Zimbabwe appears beneficial to most adult men involved in the RCT, with minimal changes in effectiveness due to income or age. Older men were more likely to respond to the texts, but this small effect does not seem programmatically meaningful. Although clients were not given airtime until day 14, response rates of almost 93% suggest that men were able and willing to pay SMS costs up front. Clients likely paid an average of $0.05 per SMS, and were asked to respond to a daily text for a minimum combined cost of $0.65, or far less if they bought text bundles. Many men exchanged further texts with the nurse, suggesting that men were able and willing to pay these SMS costs in lieu of an in-person visit that would likely require travel time, transportation, and absence from work.

The results of the quantitative and qualitative analysis suggest several key improvements for 2wT at scale. First, the nurse managing the clients urged future scale-up interventions to clarify that 2wT is not for emergency or after-hours care. This could easily be completed by an automated response recommending alternatives for seeking care after hours. Similarly, at scale more nurses would be needed to rotate responsibility for client management via the 2wT system in anticipation of client communication requests and timing; further user interface optimizations could support these programmatic changes. Moreover, most mobile network operators offer ‘reverse billed’ SMS numbers that are free to clients and paid for by the sponsoring organization; while costly for a small study, this would be viable at scale. These steps may be critical for 2wT at scale to reduce the workload on the nurse managers and ensure continuous client care.

It is also worth noting several limitations to the 2wT intervention. The majority of study clients liven in an urban setting, and it remains to be investigated whether 2wT interventions may be similarly usable among rural populations. In settings where phone ownership remains low, the efficiency gains of 2wT may be limited to a subset of the total client base. For safety and verification, our study protocol also excluded any client who did not have a phone with him at the time of enrollment and who did not receive a confirmation message from the 2wT system before leaving the clinic. 2wT at scale could opt for less strict inclusion criteria to enroll more clients and increase 2wT access; however, that could introduce patient care and verification concerns if hardware malfunctions, SIM card issues, poor electricity access, or poor cell networks jeopardized potential client contact. Consideration of these constraints or other challenges such as phone sharing were beyond the scope of the present 2wT study. Lastly, although we did not encounter high rates of refusal, there are privacy and stigma concerns among men opting for MC that affect follow-up rates. However, if men were allowed to access 2wT at any time during the healing period, without requiring 2wT enrollment at registration, 2wT could provide men with concerns an alternative pathway to access care, improving patient outcomes overall. Despite these limitations, and combined with the clinical results demonstrating safety [27], it is clear that 2wT warrants further exploration for replication and scale-up in other MC care contexts and settings.

Conclusions

Our usability and acceptability results show that post circumcision 2wT interaction for follow-up care is highly useable and acceptable for clients and healthcare professionals, contributing substantially to the successful achievement of MC program efficiencies. By designing a hybrid workflow, we were able to integrate the efficiency benefits of automated messaging with the familiarity and flexibility of human-to-human conversational texting. While our usability and acceptability findings are grounded in the clinical and operational particulars of MC, our results are largely attributable to the software and hybrid 2wT workflow rather than to a specific disease or condition, contributing to the growing applicability of 2wT in healthcare interventions in developing countries, including SSA [86–89]. Similar automated/human-to-human 2wT merits further study in other care contexts, such as childhood diseases, respiratory infections, or post-operative care that could similarly benefit from intensive, direct provider-to-client communication.

Based on our mixed-methods findings, we would emphasize four characteristics of health programs that may benefit from the hybrid automated/human-to-human workflow: 1) facility-based follow-up care is perceived as burdensome to patients and/or providers; 2) most clients heal, adhere, or otherwise succeed with routine care and standard counseling, minimizing risk; 3) clients with complications or questions are likely to be able to self-care or triage safely and effectively with the support of a remote clinician; and 4) the follow-up period is brief enough to sustain engagement and minimize obstacles due to lost phones, changed phone numbers etc. Programs with these characteristics may be more amenable to a new kind of task-shifting, in which digital tools enable clients and their care givers to be more informed, engaged, and capable of self-care in situations that otherwise might have required a visit to a health facility.

The open-source nature of our intervention should aid efforts to replicate this intervention or adapt it for other settings and care contexts. However, 2wT adaptations, replications, and advances are not without risks and not without costs. Further research on hybrid 2wT interventions across diseases and care contexts, with attention to the implementation challenges that may limit scale-up, could further establish the benefits and limitations of this new approach to digitally supported self-care in the community.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the countless contributions of the 2wT study team, Christina Mauhy, Mujinga Tshimanga, Wendy Mutepfe, and Patricia Tapiwa Gundidza, towards the success of this research study. We would also like to thank the Zimbabwe MC teams at Seke South and Norton clinics as well as Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care for their participation and collaboration on the 2wT effort. The authors would also like to thank the University of Washington / Fred Hutchinson Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program, for biostatistical support.

Data Availability

All relevant quantitative data from the client usability surveys are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files. Our complete transcripts contain data that is sensitive or includes identifying information. We also believe that the Zimbabwe MoHCC would like the confidentiality of the participants protected in accordance with the consent agreement. Due to these concerns, we are unable to make the full transcripts available to a wider audience. We will make the transcripts easily available to fellow researchers or reviewers who complete a data sharing agreement. The edited transcripts will be available on a case by case basis after reviewing all materials for any potentially identifying details. Interested researchers may contact the corresponding author, CF, at cfeld@uw.edu for copies of the transcripts. Or, researchers could also contact Jane Edelson jedelson@uw.edu, Regulatory Specialist at the UW, for access to the transcripts.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21TW010583 (CF). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56. Epub 2007/02/27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS medicine. 2005;2(11):e298 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed J, Grund J, Liu Y, Mwandi Z, Howard AA, McNairy ML, et al. Evaluation of loss-to-follow-up and post-operative adverse events in a voluntary medical male circumcision program in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebina L, Taruberekera N, Milovanovic M, Hatzold K, Mhazo M, Nhlapo C, et al. Piloting PrePex for Adult and Adolescent Male Circumcision in South Africa—Pain Is an Issue. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0138755 Epub 2015/09/26. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phili R, Abdool-Karim Q, Ngesa O. Low adverse event rates following voluntary medical male circumcision in a high HIV disease burden public sector prevention programme in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kigozi G, Musoke R, Kighoma N, Kiwanuka N, Makumbi F, Nalugoda F, et al. Safety of medical male circumcision in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men in Rakai, Uganda. Urology. 2014;83(2):294–7. Epub 2013/11/30. 10.1016/j.urology.2013.08.038 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldblum PJ, Odoyo-June E, Obiero W, Bailey RC, Combes S, Hart C, et al. Safety, effectiveness and acceptability of the PrePex device for adult male circumcision in Kenya. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e95357 Epub 2014/05/03. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS. Update: Voluntary medical male circumcision―4.1 million performed in 2018 Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019 [cited 2020 April 10]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2019/october/20191021_vmmc.

- 10.Njeuhmeli E, Forsythe S, Reed J, Opuni M, Bollinger L, Heard N, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: modeling the impact and cost of expanding male circumcision for HIV prevention in eastern and southern Africa. PLoS medicine. 2011;8(11):e1001132 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.South Africa National AIDS Council. South Africa's national strategic plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. Pretoria: South African National AIDS Council, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollinger LA, Stover J, Musuka G, Fidzani B, Moeti T, Busang L. The cost and impact of male circumcision on HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2009;12(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision For HIV Prevention In 14 Priority Countries In Eastern And Southern Africa. Geneva: WHO, 2018. July, 2018. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed JB, Njeuhmeli E, Thomas AG, Bacon MC, Bailey R, Cherutich P, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: an HIV prevention priority for PEPFAR. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2012;60(0 3):S88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGillen JB, Stover J, Klein DJ, Xaba S, Ncube G, Mhangara M, et al. The emerging health impact of voluntary medical male circumcision in Zimbabwe: An evaluation using three epidemiological models. PloS one. 2018;13(7):e0199453 10.1371/journal.pone.0199453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wamai RG, Weiss HA, Hankins C, Agot K, Karim QA, Shisana O, et al. Male circumcision is an efficacious, lasting and cost-effective strategy for combating HIV in high-prevalence AIDS epidemics. Future HIV Therapy. 2008;2(5):399–405. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geldsetzer P, Bloom DE, Humair S, Bärnighausen T. Increasing Coverage of Antiretroviral Therapy and Male Medical Circumcision in HIV Hyperendemic Countries: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran K, Njeuhmeli E, Mirelman A, Dickson K, Adamu T, Cherutich P, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: strategies for meeting the human resource needs of scale-up in southern and eastern Africa. PLoS medicine. 2011;8(11):e1001129 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. The 2018 update: Global Health Workforce Statistics. Geneva: WHO, 2018. November 6, 2019. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Njeuhmeli E, Opuni M, Schnure M, Tchuenche M, Stegman P, Gold E, et al. Scaling Up Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention for Adolescents and Young Adult Men: A Modeling Analysis of Implementation and Impact in Selected Countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;66(suppl_3):S166–S72. 10.1093/cid/cix969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. Miles to go: closing gaps breaking barriers righting injustices. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2018. Contract No.: UNAIDS/JC2924. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. A framework for voluntary medical male circumcision: effective HIV prevention and a gateway to improved adolescent boys' & men's health in Eastern and Southern Africa by 20212016 [cited 2017 July 20]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246234.

- 23.Hensen B, Taoka S, Lewis JJ, Weiss HA, Hargreaves J. Systematic review of strategies to increase men's HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(14):2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNAIDS. State of the Epidemic2019 September 19, 2019 [cited 2019 September 18, 2019]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf.

- 25.Davis SM, Hines JZ, Habel M, Grund JM, Ridzon R, Baack B, et al. Progress in voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention supported by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through 2017: longitudinal and recent cross-sectional programme data. BMJ open. 2018;8(8):e021835 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grund JM. Notes from the Field: Tetanus Cases After Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention—Eastern and Southern Africa, 2012–2015. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016;65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldacker C, Murenje V, Holeman I, Xaba S, Makunike-Chikwinya B, Korir M, et al. Reducing Provider Workload While Preserving Patient Safety: A Randomized Control Trial Using 2-Way Texting for Postoperative Follow-up in Zimbabwe's Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Program. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2020;83(1):16–23. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maponga BA, Chirundu D, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Tshimanga M, Bangure D. Evaluation of the notifiable diseases surveillance system in sanyati district, Zimbabwe, 2010–2011. The Pan African medical journal. 2014;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Country health information systems: a review of the current situation and trends: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman-Roloff A, Bailey RC, Agot K. Factors associated with the safety of voluntary medical male circumcision in Nyanza province, Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(10):773–81. Epub 2012/10/31. 10.2471/BLT.12.106112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey RC, Egesah O, Rosenberg S. Male circumcision for HIV prevention: a prospective study of complications in clinical and traditional settings in Bungoma, Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(9):669–77. Epub 2008/09/18. 10.2471/blt.08.051482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marongwe P, Gonouya P, Madoda T, Murenje V, Tshimanga M, Balachandra S, et al. Trust but verify: Is there a role for active surveillance in monitoring adverse events in Zimbabwe’s large-scale male circumcision program? PloS one. 2019;14(6):e0218137 10.1371/journal.pone.0218137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bochner AF, Feldacker C, Makunike B, Holec M, Murenje V, Stepaniak A, et al. Adverse event profile of a mature voluntary medical male circumcision programme performing PrePex and surgical procedures in Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017;(20:21394). Epub 21 February 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Progress in scaling up voluntary medical male circumcision or HIV prevention in Est and Southern Africa January-December 20122013 October 27, 2014. Available from: http://www.malecircumcision.org/country_updates/documents/Progress%20in%20scaling%20up%20VMMC_Dec2013.pdf.

- 35.Byabagambi J, Kigonya A, Lawino A, Ssensamba JT, Twinomugisha A, Karamagi-Nkolo E, et al. A Guide to Improving the Quality of Safe Male Circumcision in Uganda2015 [cited 2016 August 12]. Available from: https://www.usaidassist.org/sites/assist/files/uganda_guide_to_improving_the_quality_of_smc_a4_feb2015_ada.pdf.

- 36.Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Rech D, Doyle S, Shabangu D, Nhlapo C, et al. A model for the roll-out of comprehensive adult male circumcision services in African low-income settings of high HIV incidence: the ANRS 12126 Bophelo Pele Project. PLoS medicine. 2010;7(7):e1000309 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Voluntary medical male circumcision-southern and eastern Africa, 2010–2012. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report [Internet]. 2013 August 19, 2016; 62(47):[953 p.]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6247a3.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.World Health Organization. WHO Surgical Safety Checklist2009 February 6, 2019 February 6, 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/checklist/en/.

- 39.President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting Indicator Reference Guide. Washington DC: PEPFAR, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care. Accelerated Strategic and Operational Plan 2014–2018. Harare- Zimbabwe: 2014.

- 41.Feldacker C, Makunike-Chikwinya B, Holec M, Bochner AF, Stepaniak A, Nyanga R, et al. Implementing voluntary medical male circumcision using an innovative, integrated, health systems approach: experiences from 21 districts in Zimbabwe. Global health action. 2018;11(1):1414997 10.1080/16549716.2017.1414997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldacker C, Murenje V, Barnhart S, Xaba S, Makunike-Chikwinya B, Holeman I, et al. Reducing provider workload while preserving patient safety via a two-way texting intervention in Zimbabwe’s voluntary medical male circumcision program: study protocol for an un-blinded, prospective, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):451 10.1186/s13063-019-3470-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iso W. 9241–11. Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs). The international organization for standardization. 1998;45:9.

- 44.Abran A, Khelifi A, Suryn W, Seffah A. Usability Meanings and Interpretations in ISO Standards. Software Quality Journal. 2003;11(4):325–38. 10.1023/a:1025869312943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bevan N. International standards for HCI and usability. International journal of human-computer studies. 2001;55(4):533–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bevan N. International standards for usability should be more widely used. Journal of Usability Studies. 2009;4(3):106–13. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bevan N, Carter J, Earthy J, Geis T, Harker S, editors. New ISO standards for usability, usability reports and usability measures. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; 2016: Springer.

- 48.Borsci S, Federici S, Malizia A, De Filippis ML. Shaking the usability tree: why usability is not a dead end, and a constructive way forward. Behaviour & information technology. 2018:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science. 1989;35(8):982–1003. 10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dillon A. User acceptance of information technology. In: W K, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Factors and Ergonomics. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. Preventing AIDS: Springer; 1994. p. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS care. 2000;12(3):273–8. 10.1080/09540120050042918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology and health. 1998;13(4):623–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach: Taylor & Francis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ajzen I, Fisbbein M. Factors influencing intentions and the intention-behavior relation. Human relations. 1974;27(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jumreornvong O. New Weapon In The War Against AIDS: Your Mobile Phone. Intersect: The Stanford Journal of Science, Technology and Society. 2014;7(1). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holeman I, Kane D. Human-Centered Design for Global Health Equity. Information Technology for. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.World Health Organization. Classification of digital health interventions v1. 0: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health2018 October 1, 2019 [cited 2019 October 1, 2019]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260480/WHO-RHR-18.06-eng.pdf.

- 59.President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting Indicator Reference Guide. March 2015 ed. Washington DC: PEPFAR; 2015.

- 60.Econet. Econet Wireless Tariffs (Incl VAT) Harare, Zimbabwe2016 [cited August 2016]. Available from: https://www.econet.co.zw/services/tariffs.

- 61.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feldacker C, Bochner AF, Murenje V, Makunike-Chikwinya B, Holec M, Xaba S, et al. Timing of adverse events among voluntary medical male circumcision clients: Implications from routine service delivery in Zimbabwe. PloS one. 2018;13(9):e0203292 10.1371/journal.pone.0203292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linnemayr S, Huang H, Luoto J, Kambugu A, Thirumurthy H, Haberer JE, et al. Text messaging for improving antiretroviral therapy adherence: no effects after 1 year in a randomized controlled trial among adolescents and young adults. American journal of public health. 2017;107(12):1944–50. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2013;10(1):e1001362 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anglada‐Martinez H, Riu‐Viladoms G, Martin‐Conde M, Rovira‐Illamola M, Sotoca‐Momblona J, Codina‐Jane C. Does mHealth increase adherence to medication? Results of a systematic review. International journal of clinical practice. 2015;69(1):9–32. 10.1111/ijcp.12582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Department of Health and Human Services. Using health text messages to improve consumer health knowledge, behaviors, and outcomes: an environmental scan. 2014. URL: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/archive/healthit/txt4tots/environmentalscan.pdf [accessed 2020-05-04]. 2015.

- 67.Déglise C, Suggs LS, Odermatt P. SMS for disease control in developing countries: a systematic review of mobile health applications. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2012;18(5):273–81. 10.1258/jtt.2012.110810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devi BR, Syed-Abdul S, Kumar A, Iqbal U, Nguyen P-A, Li Y-CJ, et al. mHealth: An updated systematic review with a focus on HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis long term management using mobile phones. Computer methods and programs in Biomedicine. 2015;122(2):257–65. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeKoekkoek T, Given B, Given CW, Ridenour K, Schueller M, Spoelstra SL. mHealth SMS text messaging interventions and to promote medication adherence: an integrative review. Journal of clinical nursing. 2015;24(19–20):2722–35. 10.1111/jocn.12918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, De Walque D, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS (London, England). 2011;25(6):825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Odeny TA, Bailey RC, Bukusi EA, Simoni JM, Tapia KA, Yuhas K, et al. Effect of text messaging to deter early resumption of sexual activity after male circumcision for HIV prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014;65(2):e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Odeny TA, Bailey RC, Bukusi EA, Simoni JM, Tapia KA, Yuhas K, et al. Text Messaging to Improve Attendance at Post-Operative Clinic Visits after Adult Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e43832 10.1371/journal.pone.0043832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeRenzi B, Findlater L, Payne J, Birnbaum B, Mangilima J, Parikh T, et al. , editors. Improving community health worker performance through automated SMS. Proceedings of the fifth international conference on information and communication technologies and development; 2012: ACM. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perrier T, Dell N, DeRenzi B, Anderson R, Kinuthia J, Unger J, et al., editors. Engaging pregnant women in Kenya with a hybrid computer-human SMS communication system. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2015: ACM.

- 77.Crankshaw T, Corless IB, Giddy J, Nicholas PK, Eichbaum Q, Butler LM. Exploring the patterns of use and the feasibility of using cellular phones for clinic appointment reminders and adherence messages in an antiretroviral treatment clinic, Durban, South Africa. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2010;24(11):729–34. 10.1089/apc.2010.0146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aranda-Jan CB, Mohutsiwa-Dibe N, Loukanova S. Systematic review on what works, what does not work and why of implementation of mobile health (mHealth) projects in Africa. BMC public health. 2014;14(1):188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith J, Braunack-Mayer A, Wittert G. What do we know about men's help-seeking and health service use? 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharma M, Barnabas RV, Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men’s engagement in the HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shand T, Thomson‐de Boor H, van den Berg W, Peacock D, Pascoe L. The HIV blind spot: men and HIV testing, treatment and care in sub‐Saharan Africa. IDS Bulletin. 2014;45(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 82.McLaren ZM, Ardington C, Leibbrandt M. Distance decay and persistent health care disparities in South Africa. BMC health services research. 2014;14(1):541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.L'Engle KL, Vahdat HL, Ndakidemi E, Lasway C, Zan T. Evaluating feasibility, reach and potential impact of a text message family planning information service in Tanzania. Contraception. 2013;87(2):251–6. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perrier T, Harrington EK, Ronen K, Matemo D, Kinuthia J, John-Stewart G, et al., editors. Male partner engagement in family planning SMS conversations at Kenyan health clinics. Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies; 2018: ACM.

- 85.Murenje V, Holeman I, Tshimanga M, Korir M, Wambua B, Barnhart S, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a two-way texting intervention for post-operative follow up for voluntary medical male circumcision. 20th ICASA International Conference on AIDS and STI's in Africa; December 6, 2019; Kigali, Rwanda2019.

- 86.Martinez-Brockman J, Harari N, Pérez-Escamilla R. Lactation advice through texting can help: An analysis of intensity of engagement via two-way text messaging. Journal of health communication. 2018;23(1):40–51. 10.1080/10810730.2017.1401686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Odeny TA, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Yuhas K, Camlin CS, McClelland RS. Texting improves testing: a randomized trial of two-way SMS to increase postpartum prevention of mother-to-child transmission retention and infant HIV testing. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(15):2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Unger J, Ronen K, Perrier T, DeRenzi B, Slyker J, Drake A, et al. Short message service communication improves exclusive breastfeeding and early postpartum contraception in a low‐to middle‐income country setting: a randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2018;125(12):1620–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoeli E, Rathauser J, Bhanot SP, Kimenye MK, Mailu E, Masini E, et al. Digital Health Support in Treatment for Tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(10):986–7. 10.1056/NEJMc1806550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]