Abstract

Background:

Aggressive behaviors have increasing trend in children and adolescents all over the world. This study aimed to perform a systematic review on the association between screen time activities and aggressive behaviors.

Methods:

A systematic search was conducted through PubMed, Institute of Scientific Information (ISI), and Scopus, until 2017. Moreover, related unpublished studies (grey literature, thesis project and congress paper), considered for further data availability. Data extraction and quality assessment conducted by two independent experts.

Results:

Through searching processes, 4381 publications were found, from them. 483 papers were from PubMed database and others were from ISI/WOS (1724) and Scopus (1938). Following the excluding of non-relevant and duplicated studies, 19 studies remained for further analyzing. Findings of the present study showed that children and adolescents who share most of their time for watching of television are at greater risk for violent behaviors including physical fighting, victim and bully.

Conclusion:

This review found that children and adolescents who share most of their time for watching of television are at greater risk for violent behaviors including physical fight, victim and bully.

Keywords: Adolescents, aggressive behaviors, children, screen time

Introduction

Aggressive behaviors become an important priority in health promotion of children and adolescents all over the world. It is documented that at least 8% of children around the world are affected from bully behaviors and about 50% of them involve aggression.[1,2,3] Behavioral problems such as juvenile misbehavior, adulthood violence and criminal behavior might root from experiences of aggressive behaviors of the first years of life.[4,5]

In spite of the related investigations, there are still obvious gaps in evidence that focus on aggressive bullying behaviors and its predisposing factors. The results of studies of adolescents aggression behaviors' have discussed on different interactive factors which contributes from different domains of cognitive stimulation, emotional support and television exposure.[6,7] Recently, most of the children and adolescents spend a considerable part of their time using visual and auditory devices, including television, computer games, cell phones, tablets and personal computers.[8,9,10] Along with these situations, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that in daily program of under 2 years children, entertainment media time should be limited to 1-2 hours.

The AAP also warns about the television setting in children's bedrooms.[11] Despite of these recommendations, related investigations on daily activities of children and adolescents show that, yet most of them spend more than two hours for television watching,[12] and about 36% of 6-year-old children have televisions in their bedroom.[13]

Over the past decade, many adverse health outcomes and complications have been attributed to patterns of screen time activities.[14,15,16] Recent evidence confirmed that time spent using devices such as a computer, television or games directly raises the risk of the adverse health outcomes.[17]

Although some of published researches about relationship between aggression in children and use of visual devices show a direct relationship, there are still a few studies that present different results[6,7,15,16,18] Furthermore, there are some studies that have not been able to reach to a clear inference.

Considering the obvious gaps of required evidence for better policy making and aimed to provide the most comprehensive overview of problem, present study as a well-developed systematic review, summaries the results of published studies in scope of association of screen time activities and aggressive behaviors.

Methods

This is a systematic review on association of Screen Time (ST) and violent behaviors' in children and adolescents through which we targeted two main objectives as follow:

-

1)

Assessment of association between screen time and violent behaviors;

-

2)

Assessment of heterogeneity and finding the sources of differences.

Search strategy

To search for related resources and literature, we used more comprehensive electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed and ISI Web of Science). Moreover, related unpublished studies (grey literature, thesis project and congress paper) considered for further data availability [Table 1].

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Search strategy in PubMed/Medline |

| (“violence”[Mesh] OR “violence” [All Fields] OR “violent behaviors “ [All Fields] OR “ Assaultive Behavior “[All Fields] OR atrocitie* [All Fields]) AND (“screen time” [All Fields] OR “leisure activities”[MeSH Terms] OR leisure[Text Word] OR “Video Games”[Mesh] OR “Computer Game” [All Fields] OR “television”[MeSH Terms] OR television[Text Word] OR “personal computer” [All Fields] OR “electronic game” [All Fields] OR game* [All Fields]) AND (“Child”[Mesh] OR Child [All Fields] OR children”[All Fields] OR “Adolescent”[Mesh] OR “Adolescent”[ All Fields] OR Teen* [ All Fields] OR Youth[ All Fields]) AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms]) |

| Search strategy in ISI Web of Science |

| ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (violenc)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (violence)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“violent behaviors “)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“assaultive behavior “))) AND (((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“leisure activities”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“leisure time”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (leisure*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Video Games”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Computer Game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (television) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“personal computer”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“electronic game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (game*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (pc) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (vcd*))) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“screen time”))) |

| Search strategy in Scopus |

| (TOPIC: (violence) OR TOPIC: (violenc*) OR TOPIC: (“violent behaviors “) OR TOPIC: (“assaultive behavior “) OR TOPIC: (atrocitie*) ) AND (TOPIC: (“screen time”) OR TOPIC: (“leisure activities”) OR TOPIC: (“leisure time”) OR TOPIC: (leisure*) OR TOPIC: (“Video Games”) OR TOPIC: (“Computer Game”) OR TOPIC: (game*) OR TOPIC: (television) OR TOPIC: (“personal computer”) OR TOPIC: (“electronic game”) OR TOPIC: (VCD*) OR TOPIC: (TV)) |

| Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH Timespan=All years |

The primary keywords for developing the search strategy were including:

Violence: the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy.[19]

Screen time: time spending on watching television (TV)/VCDs, personal computer (PC), or electronic games (EG).[2,8]

Inclusion criteria

We included all of related descriptive and analytical studies (case control, cohort, cross-sectional) which were assessed the association of ST with violent behaviors in children and adolescents. There was no limitation for time of studies, time of publications and language of documents.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Quality of included documents were determined using quality assessment form which contains three main parts of; general information, sampling quality, and measurement quality. Using standardized data extraction sheet, data were extracted from eligible papers.

These processes of quality assessment and data extraction conducted by two independent researchers (Kappa statistic for agreement; 0.97). Probable discrepancy between them resolved based on third expert opinion (main investigator).

Ethical considerations

Protocol of study was approved by the ethical committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. All of the included studies would be cited in future reports and publications.

Results

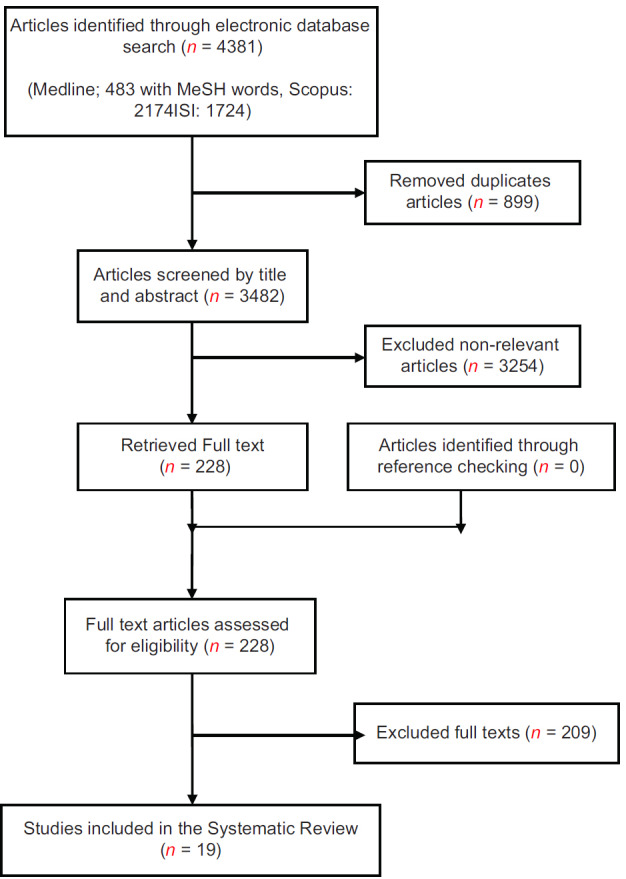

We refined data for association of screen time activities and aggressive behaviors, among children and adolescents. Through searching processes, 4381 publications were found, from them; 483 papers were from PubMed data base and other were from ISI/WOS (1724) and Scopus (1938). Following the excluding of non-relevant and duplicated studies, 19 studies remained for further analyzing [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Papers search and review flowchart for selection of primary study

All of searched documents were in English language. Considering the type of studies, 13 investigations were followed as cross-sectional surveys; 3 studies were designed as cohort studies, 2 researches were run as national longitudinal surveys and one study was a community-based longitudinal investigation. Considering the scopes of researches; 11 studied targeted the watching TV, 3 researches were conducted on playing computer, video games or using computers and 3 studies only focused on video games. Most of results confirmed that watching television is associated with bullying and violence. The characteristics of including papers and the finding and extracted results presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The characteristics of including papers and the finding and extracted results

| First author, date of publication, country | Type of study | Characteristics of participants (age, sample size, gender) | Time spent consuming media and reported frequency of violent content | Type of aggressive behaviors or violence and type of media | Main result | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marina Verlinden, 2014, Netherlands[21] | population-based cohort | 5389, boy and girl Teacher report of bullying involvement (n=3423) mean=6.8 years±3.03 months. Peer/self-report of bullying involvement (n=1176) mean=7.6 years±8.95 months |

Low= <1 hour, high>1 h, mid-low and mid high=the probabilities of watching>1 h of TV daily increased between ages 2-4 and were considerably lower at age 5 years. In Teacher report of bullying involvement group: 42% mid-low and in Peer/self-report of bullying involvement group 44.2% mid-low | Bully, Victim/TV | High television exposure class was associated with elevated risks of bullying and victimization. Also, in both teacher- and child-reported data, children in the high television exposure class were more likely to be a bully-victim (OR=2.11, 95% CI: 1.42-3.13 and OR=3.68, 95% CI: 1.75-7.74 respectively). | The association between television viewing time through ages 2-5 and bullying involvement in early elementary school is confounded by maternal and child socio-demographic characteristics. |

| Jennifer A. Manganello, 2009, US[20] | prospective cohort study | 3128 mothers, boy and girl 0.30 to 50 months (mean, 36 months) | About two-thirds (65%) of mothers reported that their index child watched more than 2 h of TV per day (mean, 3.2 [SD, 2.3]; median, 3; range, 0-24 h). After subtracting direct child TV exposure, there was an average of 5.2 hours of additional household TV use on a typical day (SD, 5.7; median, 3; range, 0-24 h) | Aggressive behavior/TV | Direct child TV exposure (β = 0.16, P 0.001) and household TV use (β = 0.09, P 0.001) were also significantly associated with childhood aggression, even when controlling for other factors. | Three-year-old children exposed to more TV, both directly and indirectly, are at increased risk for exhibiting aggressive behavior. Further research is essential to determine whether pediatric recommendations concerning TV and children should include limits for general household TV use |

| Maxine M. Denniston, 2011, GA[19] | cross-sectional | 14041 students. in grades nine through 12 | > 3 hours/day | Interpersonal violence, alcohol and drug use/watching TV and playing computer or video games | Overall, 35.4% (95% CI=33.1%-37.7%) of students reported frequent television (TV) use and 24.9% (95% CI=22.9%-27.0%) reported frequent computer/video game use. A number of risk behaviors, including involvement in physical fights and initiation of alcohol use before age 13, were significantly associated with frequent TV use or frequent computer/video game use, even after controlling for sex, race/ethnicity and grade. | Findings highlight the need for additional research to better understand the mechanisms by which electronic media exposure and health-risk behaviors are associated and for the development of strategies that seek to understand how the content and context (e.g., watching with peers, having computer in common area) of media use influence risk behaviors among youth |

| ELIF N ÖZMERT, 2011, Turkey[22] | cross-sectional survey | 581 (332 female, 249 male). 13.5±0.7 (12-16 years). | The mean duration of TV viewing was 2.32±1.77 hours/day according to parents and 2.08±1.41 hours/day according to self-report | Aggressive behavior/TV | The linear regression analysis revealed a statistically significant relation between socioeconomic status (P=0.019) and aggressive behavior score of CBCL (P=0.016) and parent reported TV viewing hours. Self-reported TV viewing for more than 2 h was significantly associated with social problem score (OR 1.17; 95% CI: 1.016-1.349; P=0.030) and having a TV in bedroom (OR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.065-2.731, P=0.026). | The linear regression analysis for family reported TV viewing hours revealed significance for socio-economic status (P=0.019) and aggressive problem score (P=0.016). Binary logistic analysis for self-reported TV viewing for more than 2 hours was associated significantly with social problem score (OR 1.17, 95 % CI 1.016-1.349; P=0.030) and having a TV in bedroom (OR 1.706, 95% CI: 1.065-2.731, P=0.026). |

| Ian Janssen, 2012, Canada[23] | prospective cohort | 9,672 Canadian youth in grades 6-10 and a 1-year longitudinal sample of 1,861 youth in grades 9-10. | The median weekly screen time values were 17 h for television, 9 h for computer, and 7 h for video games in the cross-sectional sample. The corresponding values were 16 h, 14 h, and 4.5 h for the longitudinal sample. | physical fights and/or episodes of physical bullying/watching television, playing video games, and using a computer | In the cross-sectional sample, computer use was associated with violence independent of television and video game use. Video game use was associated with violence in girls but not boys. Television use was not associated with violence after controlling for the other screen time measures. In the longitudinal sample, video game use was a significant predictor of violence after controlling for the other screen time measures. | Computer and video game use were the screen time measures most strongly related to violence in this large sample of youth. |

| EMIL G. M. 1997, Netherlands[24] | cross-sectional survey | 346 children consisted of 175 girls and 171 boys 0.7th and 8th grade from seven elementary schools mean=11.5 years | About 70% of the children played videogames at least once in the week concerned. Only 16 children (5%) had played videogames every day of the week. Of the children in our study, 3% indicated that their time playing videogames averages more than 2 hr per day. About 6% played between 1 and 2 hr per day, 14% played between 30 min and 1 hr per day, and 48% played less than 30 min per day on average | sticking out their tongues, telling lies, and fighting/video games | There was no significant relationship between the amount of time children spent on videogames and aggressive behavior. A negative relationship between time spent playing videogames and social behavior was found; however, this relationship did not appear in separate analyses for boys and girls | there was no significant relationship between judgments on the amount of aggressive behavior and the amount of time a child spent playing videogames |

| S. Liliana Escobar-Chaves, 2002, USA.[25] | cross-sectional survey | 5,831 students 49.9%males and 50.1% females’. from 11 to 16 years mean age: 13.2. | Only 5% of the students played video games four or more hours during the week, and 9% played four or more hours during the weekend. Both during the weekdays and the weekends, boys were four times more likely than girls to play four or more hours of video games. | teasing, pushing, name-calling, hitting, encouraging students to fight, kicking, threatening to hurt or hit, and getting angry easily/video games | A linear relationship was observed between the time spent playing video games and aggression scores. Higher aggression scores were significantly associated with heavier video playing for boys and girls (P<0.0001). The more students played video games, the more they fought at school (P<0.0001). | Higher aggression scores were significantly associated with heavier weekday video game playing (F (4, 5103) = 73.6, P<0.0001) as well as with heavier weekend video game playing (F (4, 5083) = 48.5, P<0.0001). |

| Mukaddes Demirok, 2012, Turkey[26] | cross-sectional survey | Four hundred : 231 male and 169 female students. ages of 15-18 (M=16.2, SD=0.90). | Thirty-one per cent (n=131) played every day, while 43% (n=180) played 3-4 days a week. Only 11.8% of students (n=49) played one day a week, 5.3% (n=23) one day a fortnight, and 4% (n=17) less than once a fortnight. | Expressing anger. These dimensions include ‘Anger Control’ (8 items, α = 0.87), ‘Anger-Out’ (8 items, α = 0.91) and ‘Anger-In’ (8 items, α = 0.90)./played computer games | The results showed that students who played computer games for 30 minutes a day reported a lower level of trait anger compared to others. They also reported less external aggression. | It was found that students who played computer games for 2-3 h a day scored higher on expressed anger than those who played for less than half an hour a day. |

| Cheryl K. Olson, 2009, USA[27] | cross-sectional survey | 1069 male and females/8th grade | not reported | Delinquent behaviors (damaging property for fun, stealing from a store, skipping school, or getting in trouble with the police) and physical aggression (hitting or beating up someone, or getting in physical fights)/‘‘computer games, video games and handheld games | Even after controlling for a variety of possible confounding variables, exposure to M-rated games remained a strongly significant predictor of engaging in bullying and physical aggression. Further, this relationship was dose-related: each additional day-per-week category of exposure to M-rated games increased the probability of bullying behavior by 45%. | M-rated game dose predicted greater risk for bullying (P<0.01) and physical fights (P<0.001), but not for delinquent behaviors or being a victim of bullies. When analyzed separately, these associations became weaker for boys and stronger for girls. |

| Jeffrey G. Johnson, 2002, USA[28] | a community-based longitudinal investigation | 707 families with a child (51% male). ages of 1 and 10, The mean age of the youths was 5.8 (SD=3) in 1975, 13.8 (SD=3) in 1983, 16.2 (SD=3) in 1985-86, 22.1 (SD=3) in 1991-93, and 30.0 (SD=3) in 2000. | from <1 h to 1 to 3 hours per day of television viewing | Assault or physical fights resulting in injury, Robbery, threats to injure someone, or weapon used to commit a crime, Any aggressive act against another person/Television viewing | Aggressive behaviors at mean age 14 were not associated with subsequent television viewing after the covariates were controlled statistically. However, youths who committed assaults or participated in fights resulting in injury at mean age 16 spent significantly more time watching television at mean age 22 than did the remainder of the youths in the sample (2=10.94; df=2; P=0.004). | There was a significant association between the amount of time spent watching television during adolescence and early adulthood and the likelihood of subsequent aggressive acts against others. |

| Oene Wiegman, 1998, Netherlands[29] | cross-sectional | 278 (144 girls and 134 boys). seventh and eighth :average age children was 11.5 | About 70 per cent of the children indicated that they played video games at least once in the week concerned. Only 17 children (6 per cent) had been playing video games every day of the week. | sticking out their tongue, telling lies and fighting/playing video games | No significant difference was found between the group of heavy players, moderate players and non-players. | No significant relationship was found between video game use in general and aggressive behavior. |

| Linda Heath, 1986, USA[30] | case - control | 93 males (48 males incarcerated for violent crimes and 45 non incarcerated). retrospective television viewing: 8, 10, and 12 years, the time of our interviews: between 18 and 25 years of age. | Inmates reported viewing an average of ten violent television programs a week, and the comparison sample of respondents reported viewing an average of eight violent shows a week. Inmates watched a mean of 33 programs per week, while the comparison group mean was 28 programs per week. The pattern of results in regard to nonviolent programming was also in this direction, with inmates reporting watching 23 programs per week, compared with 19 programs per week for the control group. |

Murder, rape, robbery , sexual or physical assault/TV | Results show that the extent of a respondent’s reported television viewing was not, in and of itself, predictive of violent criminal acts. | The television exposure variables (total viewing, violence viewing, and nonviolence viewing) enter all of the discriminant equations, but none of the equations provides particularly strong predictions of violent behavior. |

| MARK I. SINGER, 1998, USA[31] | cross-sectional | 2245 students, (50.9%were boys). mean=11±1.8 | Most students (66%) watched 3 or more hours of television per day. In addition, more than one third (36%) of students reported watching 5 or more hours of television per day. | threatening others, slapping, punching, hitting beating-up, attacking someone with a knife/TV | A linear trend was noted beginning at 1 to 2 hours, with a sharp increase between 5 to 6 hours and more than 6 hours of television viewing per day. Categories of 5 to 6 hours and lower were collapsed into a single category (0) and a point biserial correlation was calculated, resulting in a coefficient of 0.19 (P<0.00l). | children who report watching greater amounts of television per day will report higher levels of violent behaviors than children who report watching lesser amounts of television per day. |

| Vincent Busch, 2013, Netherlands.[32] | cross-sectional survey | (N=2425). Mean in years: Boys=13.7, Girls=13.9. Total=13.8. (range 11-18 years). |

Watching TV (>14h/week):boys=271 (25.9%), girls=324 (24.5%), total 595 (25.1%). Internet Use>14/week):boys=288 (27.3%), girls=340 (25.5%), total=628 (26.3%). Video Game Playing (>14/week):boys 48 (4.6%), girls=8 (0.6%), total=56 (2.3) | Bullying/Watching TV, Internet Use, Video Game Playing | Screen time was associated with bullying, being bullied. | Screen time was of significant importance to adolescent health. Behavioral interrelatedness caused significant confounding in the studied relations when behaviors were analyzed separately compared to a multi-behavioral approach, which speaks for more multi-behavioral analyses in future studies. |

| RoyaKelishadi, 2015, Iran[33] | cross-sectional | 13,486 children and adolescents (50.8% boys ). aged 6-18 years, Mean (SD) age was 12.47 (3.36) years | (>2 hrs/≤2 hrs) | physical fights, bullying and being bullied/Watching TV, Using a computer, Screen activity | The risk of physical fighting and quarrels increased by 29% (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.19-1.40) with watching TV for 0.2 hr/day, by 38% (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.21-1.57) with leisure time computer work of 0.2 h/day, and by 42% (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.28-1.58) with the total screen time of 0.2 hr/day. Watching TV or leisure time spent on a computer or total screen time of 0.2 hr/day increased the risk of bullying by 30% (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.18-1.43), 57% (1.57, 95% CI 1.34-1.85) and 62% (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.43-1.83). | Prolonged leisure time spent on screen activities is associated with violent and aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. In addition to the duration of screen time, the association is likely to be explained also by the media content. |

| Lindsay A, 2013, New Zealand[34] | cross-sectional | 5 to 15 years | more than 1 to 2 hours of television each day | antisocial behavior/TV | Excessive television viewing in childhood and adolescence is associated with increased antisocial behavior in early adulthood. The findings are consistent with a causal association and support the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation that children should watch no more than 1 to 2 h of television each day. | Young adults who had spent more time watching television during childhood and adolescence were significantly more likely to have a criminal conviction, a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, and more aggressive personality traits compared with those who viewed less television. |

| Kamila B, 2007, Maryland[35] | Prospective longitudinal study | 2707 children whose mothers completed telephone interviews at both 30 to 33 months and 5.5 years and reported television exposure at both time points. at 30-33 months and 5.5 years | Sixteen percent of parents reported that their child watched 2 hours of television daily at 30 to 33 months only, 15% reported 2 hours of television daily at 5.5 years only, and 20% reported 2 hours of television daily at both times. | aggressive behavior/Television viewing daily, including videos, and having a television in the child’s bedroom | Sustained exposure is a risk factor for behavioral problems, whereas early exposure that is subsequently reduced presents no additional risk. | Sixteen percent of parents reported their child watched 2 hours of television daily at 30 to 33 months only (early exposure) and 15% reported 2 hours of television daily at 5.5 years only (concurrent exposure). A higher percentage of parents, 20%, reported that their child watched 2 hours of television daily at both times (sustained exposure). |

| Linda S. Pagani, 2010, Michigan[36] | Prospective longitudinal study | 1314 (of 2120) children. Fourth grade (mean [SD] age, 121.83 [3.11] months). | Television exposure at 29 months was a mean (SD) of 8.82 (6.17) h for the entire week and rose to 14.85 (8.05) h per week by 53 months | Physical aggression/Television viewing | every additional hour of television exposure at 29 months corresponded to10% unit increases in victimization by classmates (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.05) | every additional hour of television exposure at 29 months corresponded to10% unit increases in victimization by classmates (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.05) |

| Frederick J. Zimmerman, 2005, Washington[37] | National Longitudinal Survey | 1266 children (Female, % 48.7).9.19±1.66 years. | Television viewing at age 4 years, h/d=3.47±3.92 | Bullies/Television viewing | Each hour of television viewed per day at age 4 years was associated with a significant odds ratio of 1.06 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.11) for subsequent bullying. | Exposure to television, has a significant impact on bullying in grade school. |

The topic of target studies were categorized as follows:

Studying association between aggressive behavior and watching TV (5 articles);

Studying association between Bullying and watching TV (6 articles);

Studying association alcohol and drug use and watching TV (2 articles);

Studying association of other behaviors and watching TV (6 articles).

Results of qualitative synthesis

-

Studying association between aggressive behaviors and watching TV

A total of 5 articles (including 2 cross-sectional and 3 prospective cohort studies) had reported the results of assessments of linear regression analysis or coronation evaluations between aggressive behavior and watching TV [Table 2]. All of these researches reported that watching TV is associated with aggressive behaviors. They mostly focused on different aspects of physical aggressive behaviors

In this regard, a prospective cohort study through 30 to 50 months (mean, 36 months) follow up of 3128 participants (mothers) cleared that 65% of children watch television for more than two hours per day. This investigation confirmed that watching television is significantly associated with childhood aggression, even when controlling for other factors[20]

Based on a cross-sectional survey on 581 (332 female, 249 male) participants with mean age of 13.5 ± 0.7 (12-16 years); the mean duration of watching TV was 2.32 ± 1.77 hours/day. In this study, there was a significant association between socio-economic status and aggressive score (P = 0.016)

Another related community-based longitudinal investigation on children show a significant association between the amounts of time spent on watching television and aggressive behaviors. The researchers emphasized on the association between watching TV and consequences, including beatings, physical violence, theft, and crime[22]

Two other prospective longitudinal study on 2707 participants with two time point of at both 30 to 33 months and 5.5 years for follow up explained that 16% of children watched TV for more than 2 hours. They finally concluded that, sustained watching TV could act as a risk factor for mental health.[29] Another prospective longitudinal study with 1314 participants shown that, one hour of watching TV lead to 10% increased risk of physical conflict with Classmate (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.05).[30]

-

Studying association between Bullying and watching TV There are 6 studies mainly concentrated on bullying and watching TV. One of them designed as cross sectional and other followed through prospective cohorts

A population-based cohort on 5389, boy and girl relied on their teachers report of bullying involvement (N = 3423) mean = 6.8 years ± 3.03 months and peer/self-report of bullying involvement (N = 1176) mean = 7.6 years ± 8.95 months. This investigation revealed that watching TV could act as a risk factor for conflict with Classmate[16]

Another cohort study on 9,672 Canadian youth shown that computer and video games associated with violent behaviors. Through this study, the average time spending for television, computer and video games were respectively 7, 9 and 7 hours/week.[38] A cross-sectional survey on 1069 male and females from 8th grade confirmed that computer games is a significant dose-related, predictor of engaging in bullying and physical aggression[39]

Other similar cross sectional study on 2425 participants confirmed this association.[26] Through another experiences, 13,486 children and adolescents (50.8% boys), aged 6-18 years, with Mean (SD) age of 12.47 (3.36) years, studied for their physical fights, bullying and being bullied and their association with watching TV, using a computer, screen activity. Based on the results, the risk of physical fighting was associated with watching TV (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.19-1.40) and computer games (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.21-1.57)[27]

Other research groups found that, in children 4 years old, each hour of watching TV could lead to increased risk for bullying and physical aggression (OR 1.06, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.11)[31]

-

Studying association alcohol and drug use and watching TV

There were two related studies in this field. Through one of them, 14041 students, in grades nine through 12, involved in a cross-sectional study. The proportion of watching TV and computer/video game were respectively; 35.4% (33.1-37.7%) and 24.9% (22.9-27.0%). Risky behavior, including involvement in physical fights and initiation of alcohol use before were significantly associated with frequent watching TV or frequent computer/video game.[18] In another study, on 346 children with mean age of 11.5 years, there was found to be no significant association between the amount of time children spent on video games and aggressive behavior.[40]

-

Studying association of other behaviors and watching TV

Through 6 remained studies, discussed on different aspects of; verbal aggressive,[23,41] angriness,[42] Murder, rape, robbery, sexual or physical assault,[24] threatening[25] and antisocial behavior[28] aggressive behaviors [Table 2].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study that examined the association of screen time and aggressive behaviors. The assessment categorized under four main line of aggressive behavior, bullying, alcohol and drug use and other behaviors. Following the excluding of non-relevant and duplicated studies, 19 studies remained for further analyzing.

Findings of present study showed that children and adolescents who share most of their time for watching of television are at greater risk for violent behaviors including; physical fighting, victim, and bully. These results consistent with previous studies that shown behavioral disorders are less common in children and adolescents who spend more time with their families and enjoy from the families supports.[19,20,21] The role of family supports in decreasing of behavioral disorders especially emphasized in children who benefitting from emotional and social support of their parents.[19,20,21] Related studies show that, more than 2 hours/day, screen time through which children engaging on watching TV or playing video games is associated with incidence, of violent behaviors.[43,44,45]

Related investigation discussed that some related components such as higher socio-economic status of families, interactive communication skills, more attention to emotional needs of children and even higher educational levels of parents could be affect as factors that reduce the risk of violent behavior in children.[7,38,46]

Considering the above, monitoring and supervising of these concern could greatly reduce the risk of violent behaviors in children and adolescents and even in their adulthood life.[40,41] Required preventive and controlling strategies should be followed by the implementation of enhanced procedures developed based on reliable evidence. These approaches also turn on the paths of evaluation of corresponding interventional programs.[40,41]

Aim to design and implementation of such interventions, on time diagnosis of behavioral disorders is important subject that must be followed through multi-dimensional diagnostic approaches.[40,41,42] Another discussed approach is screening the abused or neglected children, that could benefitting from effective coping strategies and appropriate psychological interventions.[39]

The present study benefiting from many strengths. Considering the priority of problem, we conducted a comprehensive systematic review on association screen time activity and aggressive behaviors among children and adolescents that included all available data of eligible related studies. At the same time, present investigation has some limitations.

Conclusion

This is the comprehensive systematic review on association screen time activity and aggressive behaviors among children and adolescents. Our findings suggested that children and adolescents who share most of their time for watching of television are at greater risk for violent behaviors including physical fight, victim, and bully. These evidence could be used for development of interventional programs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Glew G, Rivara F, Feudtner C. Bullying: Children hurting children. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:183–90. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-6-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jari M, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Ardalan G, Kelishadi R. A nationwide survey on the daily screen time of Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:224–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasburger VC, Wilson BJ, Jordan AB. Children, Adolescents, and the Media. Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffitt TE. Juvenile delinquency and attention deficit disorder: Boys' developmental trajectories from age 3 to age 15. Child Dev. 1990;61:893–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill KG, Howell JC, Hawkins JD, Battin-Pearson SR. Childhood risk factors for adolescent gang membership: Results from the seattle social development project. J Res Crime Delinq. 1999;36:300–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons RL, Robertson JF, Downs WR. The nature of the association between parental rejection and delinquent behavior. J Youth Adolesc. 1988;18:297–310. doi: 10.1007/BF02139043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:349–71. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai Y, Chen S, Laurson KR, Kim Y, Saint-Maurice PF, Welk GJ. The associations of youth physical activity and screen time with fatness and fitness: The 2012 NHANES National Youth Fitness Survey. PloS One. 2016;11:e0148038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greca JP, Silva DA, Loch MR. Physical activity and screen time in children and adolescents in a medium size town in the South of Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.rppede.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandercock GR, Ogunleye AA. Screen time and passive school travel as independent predictors of cardiorespiratory fitness in youth. Prev Med. 2012;54:319–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan M, Bar-on M. Media education. Pediatrics. 1999;104:341–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Certain LK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2002;109:634–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rideout VJ, Vandewater VJ, Wartella EA. Zero to Six: Electronic Media in the Lives of Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waters E. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity. A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2000;136:703–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Children's television viewing and cognitive outcomes: A longitudinal analysis of national data. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:619–25. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson DA, Christakis DA. The association between television viewing and irregular sleep schedules among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:851–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dictionary C. Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary PONS-Worterbucher, Klett Ernst Verlag GmbH. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson T. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1561–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denniston MM, Swahn MH, Hertz MF, Romero LM. Associations between electronic media use and involvement in violence, alcohol and drug use among United States high school students. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:310–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manganello J, Taylor C. Television exposure as a risk factor for aggressive behavior among 3-year-old children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1037–45. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verlinden M, Tiemeier H, Veenstra R, Mieloo CL, Jansen W, Jaddoe VW, et al. Television viewing through ages 2-5 years and bullying involvement in early elementary school. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Özmert EN, Ínce T, Pektas A, Özdemir R, Üçkardes Y. Behavioral correlates of television viewing in young adolescents in Turkey. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:229–31. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen I, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Screen time and physical violence in 10 to 16-year-old Canadian youth. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:325–31. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schie EG, Wiegman O. Children and videogames: Leisure activities, aggression, social integration, and school performance. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1997;27:1175–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escobar SL, Kelder S, Orpinas P. The relationship between violent video games, acculturation, and aggression among Latino adolescents. Biomedica. 2002;22:398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demirok M, Ozdamli F, Hursen C, Ozcinar Z, Kutguner M, Uzunboylu H. The relationship of computer games and reported anger in young people. J Psychol Couns Sch. 2012;22:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson CK, Kutner LA, Baer L, Beresin EV, Warner DE, Nicholi AM., II M-rated video games and aggressive or problem behavior among young adolescents. Appl Dev Sci. 2009;13:188–98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes EM, Kasen S, Brook JS. Television viewing and aggressive behavior during adolescence and adulthood. Science. 2002;295:2468–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1062929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiegman O, Schie EG. Video game playing and its relations with aggressive and prosocial behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 1998;37:367–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heath L, Kruttschnitt C, Ward D. Television and violent criminal behavior: Beyond the bobo doll. Violence Vict. 1986;1:177–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer MI, Slovak K, Frierson T, York P. Viewing preferences, symptoms of psychological trauma, and violent behaviors among children who watch television. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 1998;37:1041–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busch V, Ananda Manders L, Rob Josephus de Leeuw J. Screen time associated with health behaviors and outcomes in adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37:819–30. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.6.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Ardalan G, Jari M. Relationship between leisure time screen activity and aggressive and violent behaviour in Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV Study. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2015;35:305–11. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2015.1109221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson LA, McAnally HM, Hancox RJ. Childhood and adolescent television viewing and antisocial behavior in early adulthood. Pediatrics. 2013;131:439–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mistry KB, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, Borzekowski DL. Children's television exposure and behavioral and social outcomes at 5.5 years: Does timing of exposure matter? Pediatrics. 2007;120:762–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagani LS, Fitzpatrick C, Barnett TA, Dubow E. Prospective associations between early childhood television exposure and academic, psychosocial, and physical well-being by middle childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:425–31. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmerman FJ, Glew GM, Christakis DA, Katon W. Early cognitive stimulation, emotional support, and television watching as predictors of subsequent bullying among grade-school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:384–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumpfer KL, Summerhays JF. Prevention approaches to enhance resilience among high-risk youth. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2006;1094:151–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stirling J, Amaya-Jackson L. Understanding the behavioral and emotional consequences of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2008;122:667–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, Moore RE, Cohen P, Alegria M, et al. Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 1999;38:1081–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford T. Practitioner review: How can epidemiology help us plan and deliver effective child and adolescent mental health services? J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2008;49:900–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:765–94. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ. Media as a public health issue. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:445–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimes T, Bergen L. The epistemological argument against a causal relationship between media violence and sociopathic behavior among psychologically well viewers. Am Behav Sci. 2008;51:1137–54. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savage J. The role of exposure to media violence in the etiology of violent behavior: A criminologist weighs in. Am Behav Sci. 2008;51:1123–36. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shanahan L, Copeland W, Jane Costello E, Angold A. Specificity of putative psychosocial risk factors for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2008;49:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]