Abstract

Background:

Hypertension is a major cause of noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease. Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran by meta-analysis.

Methods:

The search was carried out using authentic Persian and English keywords in national and international databases including IranMedex, Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, IranDoc, Medlib, ScienceDirect, PubMed , Scopus, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar search engine without any time limitation until 2017. Heterogeneity of studies was assessed using I2 statistic . Data were analyzed using STATA 11.1.

Results:

In 66 reviewed studies with a sample of 111,406 participants, the prevalence of hypertension was 44% in Iranian patients with cardiovascular disease 67%(95%CI: 38%–49%) in women and 42% in men. The prevalence of systolic hypertension in cardiac patients was 25%, diastolic 20%, diabetes 27%, and overexposure 43%. The prevalence of hypertension was 44% in patients with coronary artery disease, 50% in myocardial infarction, 33% in aortic aneurysm, and 44% in cardiac failure.

Conclusions:

Hypertension has a higher prevalence in women with cardiovascular disease than men, and it increases with age. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction patients have the highest levels of hypertension. The prevalence of systolic hypertension in cardiac patients is higher than diastolic hypertension.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, Iran, meta-analysis

Introduction

Chronic illness has the greatest impact on psychological function, and subsequently, quality of life, self care, physical and social performance is also affected.[1,2,3] Cardiovascular diseases are the most common chronic diseases among the middle-aged that affects the quality of life.[4,5] High blood pressure is the increase in pressure from the bloodstream to the wall of the blood vessels.[6] According to the World Health Organization, hypertension is systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg.[7] If not treated, the disease causes many complications in vital organs such as the kidneys, the brain, the eyes, and the heart.[8] This study has shown that hypertension is one of the major causes of disability and mortality, and a relative reduction in blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and renal failure.[7] In fact, the higher the risk of hypertension, the greater the chance of stroke, heart attack, heart failure, and renal failure.[9] In 2000, the global prevalence of hypertension was 26.4%, and it is predicted that by 2025, about 1.54 billion adults would suffer from this disease.[10]

With a prevalence of 39%, cardiovascular diseases are the first cause of death in Iran and are the most common cause of premature death in different societies, and about 138,000 deaths are reported every year.[7,11] Considering that hypertension is a global problem, the relationship between the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension is a long-lasting relationship, and therefore, prevention and control of hypertension are considered as highly important public health goals.[12] Overall, high blood pressure is one of the most important risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) and the most common cause of heart failure. Changes in epidemiological pattern of diseases in developed and developing countries, increased life expectancy, increase in psychological stress caused by urbanization, and changes in eating habits made this disease a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease.[10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Considering that various studies in Iran reported different statistics ranging from 4%[20] to 91%[21] for the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients, the need for a meta-analysis study seems necessary.

Materials and Methods

Study protocol

The present study is a systematic review and meta-analysis study of the prevalence of hypertension in Iranian cardiovascular patients. This study was conducted based on the Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis[1] statement, which is concerned with systematic review and meta-analysis studies. Based on this protocol, all stages of the research methodology such as search, selection of studies, qualitative assessment of studies, and data extraction from the studies were conducted by two researchers independently. If there was a difference in the report of the researchers, the third researcher investigated and resolved the dispute.[22]

Search strategy

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran by reviewing existing articles from 1985 to 2017. To collect data, national and international databases including IranMedex, Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, IranDoc, Medlib, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and the Google Scholar search engine were used.

The search was carried out independently by two researchers using Persian keywords and their English equivalent (“Iran,” “Meta-analysis,” “Cardiovascular,” and “Hypertension”). For the comprehensiveness of the search, the keywords were combined using “OR” and “AND” operators, and references to all articles related to the subject were also manually examined.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The main criteria for inclusion in this study were reference to the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients. Exclusion criteria included lack of relevance to the subject, inadequate data, statistical community other than cardiac patients, and non-random sample size.

After analyzing the inclusion and exclusion criteria and determining the related studies, the methodological quality of the studies was examined by two researchers. For this purpose, the standard STROBE checklist was used.[23] This checklist consists of 22 different sections that assess various aspects of the methodology including sampling methods, variable measurement, statistical analysis, modification of confounding variables, validity and reliability specifications of the tools used, and the objectives of the study.

Study selection

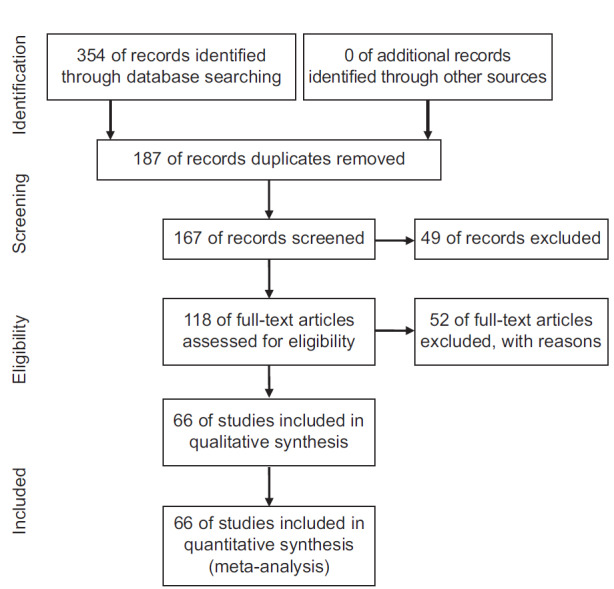

Based on the description presented in the first step, 354 possibly related articles were found on the prevalence of hypertension in cardiac patients. Out of these articles, 187 articles were removed due to duplication. Abstract of the remaining 167 articles was reviewed, and 49 other articles were omitted. The full text of 118 remaining articles was reviewed, and 52 articles were deleted due to meeting the exclusion criteria. Finally, 66 articles entered the meta-analysis process [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Diagram of the process of selecting studies for systematic review and meta-analysis

Data extraction

To reduce reporting bias and error in data collection, two researchers independently extracted data from articles and entered the data into a checklist containing the following items: name of the first author, title of study, sample size, year and place of research, the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients based on gender, the prevalence of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, prevalence of diabetes, overweight, body mass index (BMI) in cardiovascular patients, and so on.

Statistical analysis

To analyze and combine the results of various studies, the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients was considered as a binomial probability distribution, and its variance was calculated by binomial distribution in each study. Heterogeneity of studies was investigated using Q test and I[2] index. Regarding the heterogeneity of the studies, the random effect model was used to combine the results of various studies. The data were analyzed using STATA Ver. 11 and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Meta-regression model was used to examine the relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients and the sample size and year of research. The sensitivity analysis was used to determine whether omitting one study would affect the final meta-analysis result.

Results

In systematic review of studies, 66 articles with a sample size of 111,406 entered the meta-analysis process. The characteristics of the reviewed articles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specifications of the articles that entered the meta-analysis step

| (References) Author | Age | Year of study | City | Type of cardiovascular disease | Sample size | Prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular disease (%) | Prevalence of diabetes in cardiovascular disease (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24]Separham | <45 | 2006 | Isfahan | Coronary artery disease | 216 | 33.4 | - |

| [25]Tavasoli | 2-16 | 1985-2009 | Tehran | - | 9 | 88.8 | - |

| [26]Aghaei Shahsavari | 59.6 | 2004-2005 | Tabriz | Cardiovascular | 476 | --- | - |

| [27]Azizi | >3 | 1999-2001 | Tehran | Cardiovascular | 15,005 | 20.4 | 58.4 |

| [28]Saghafi | 25-64 | 2006 | Tehran | PCAD | 144 | 29.9 | 9 |

| [29]Ghaffari | 61.3 | 2008-2013 | Tabriz | Myocardial infarction | 1017 | --- | 6 |

| [30]Shirzad | >7 | 2001-2008 | Tehran | Undergone isolated coronary | 15,550 | 52.3 | - |

| [31]Masoudi kazem abad | 56.9 | 2012 | Mashhad | Coronary artery disease | 609 | 45.3 | - |

| [32]Haj Sadeghi | 59 | 2008-2009 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 123 | 57 | - |

| [33]Peyman | 62.6 | 2009 | Ilam | Cardiovascular | 60 | 56.7 | 31.2 |

| [34]Abbasalizad | 59 | 2016 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 454 | 50.4 | - |

| [35]Baharvand Ahmadi | 58.1 | 2011-2012 | Lorestan | coronary artery disease | 170 | 35.2 | - |

| [36]Bagheri | 57.2 | 2016 | Mazandaran | coronary artery disease | 238 | 62.1 | 25.2 |

| [37]Rashidi | 50-70 | 2005-2009 | Ahvaz | Aortic Aneurysm | 36 | 22.2 | - |

| [38]Zand Parsa | 61.2 | 2015 | Tehran | coronary artery disease | 414 | 54.7 | - |

| [39]Asghari | 62.7 | 2013 | Tabriz | Acute myocardial infarction | 182 | 51.6 | 27.3 |

| [40]Ostovan | 62.24 | 2011 | Shiraz | Coronary artery disease | 246 | 58.9 | - |

| [41]Montazeri | 64.83 | 2009-2010 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 100 | 84 | 41.9 |

| [42]Ahmadi | 61.2 | 2012 | Myocardial infarction | 20750 | 35.5 | 34 | |

| [43]Hashemi petrodi | 43.3 | 2014 | Sari | Myocardial infarction | 101 | 24.5 | 22.2 |

| [44]Jalal zadeh | 61.7 | 2012 | Tehran & Zanjan | Coronary artery disease | 300 | 83.7 | - |

| [45]Baharvand Ahmadi | 2011-2012 | Khorramabad | Coronary artery disease | 160 | 47 | 52 | |

| [46]peighambari | 60.45 | 2007-2012 | Tehran | Aortic valve stenosis | 407 | 41.5 | 22 |

| [47]Jouyan | 46 | 1990 | Shiraz | premature coronary artery disease | 321 | 12.5 | 30.1 |

| [48]Jahangiri | 50-70 | 2013 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 300 | --- | 17.4 |

| [49]Bakhsian-Kelarijani | 56.8 | 2003-2005 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 9709 | 40.3 | 6 |

| [50]Abbasi Tanshizi | 53.56 | 2008-2009 | Mashhad | Coronary artery disease | 128 | 29.7 | 16.6 |

| [51]Pishkar Monfared | >15 | 2006 | Sistan & Baluchestan | Coronary artery disease | 614 | 43.7 | - |

| [52]Najafipour | 15-75 | 2009-2011 | Kerman | Coronary artery disease | 5900 | 18.4 | 32.5 |

| [53]Maddah | 58 | 2010-2011 | Rasht | Coronary artery disease | 288 | 69.8 | - |

| [20]Moeini | 60-99 | 2007-2008 | Isfahan | Cardiovascular | 2063 | 4 | - |

| [54]Zand Parsa | 59.9 | 2010-2011 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 165 | 72.1 | - |

| [55]Hosseini | 57.8 | 2003-2007 | Tehran | Percutaneous coronary intervention | 195 | 63 | 43 |

| [56]Bagheri | 58.7 | 2007-2011 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 1390 | 49.5 | 45.2 |

| [57]Yarbeigi | 60.39 | 2009-2013 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 1592 | 63.5 | - |

| [58]Sadeghi | 58.9 | 2008 | Isfahan | Coronary artery disease | 125 | 36.8 | 47.3 |

| [15]Alizadeh Asl | 59.9 | 2007-2008 | East Azerbaijan | Cardiovascular | 12,031 | 43.8 | 26.4 |

| [59]Yousefi | 58.4 | 2008-2009 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 2097 | 43.9 | 36.4 |

| [60]Gholamrezanezhad | 55.3 | 2009 | Tehran | SPECT_MPI | 291 | 50.2 | 28 |

| [61]Rostami | 60.53 | 2006 | Isfahan | Coronary artery disease | 107 | 14 | 21.6 |

| [62]Eskandarian | 60.9 | 2004-2006 | Semnan | Coronary artery disease | 433 | 51 | 11.2 |

| [63]Bayani | 54.4 | 2011 | Mashhad | Cardiovascular | 238 | 37.9 | 25.2 |

| [64]Shirani | 61.7 | 2005-2006 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 2819 | 4.1 | - |

| [65]Shirani | 60.9 | 2005-2006 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 2044 | 32.2 | 3 |

| [66]Fakhrzadeh | 47.1 | 2000 | Qazvin | Coronary artery disease | 846 | 9.6 | 28.9 |

| [67]Sarrafzadegan | 59.9 | 2008 | Isfahan | Coronary artery disease | 226 | 44.5 | 12.8 |

| [68]Behboudi | 60.8 | 2008-2009 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 71 | 47.9 | - |

| [69]Naserhosseini | 57 | 2007 | Mazandaran | Coronary artery disease | 153 | 37.9 | 35.2 |

| [70]Kasaei | 56.47 | 2005-2006 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 1533 | 42 | - |

| [71]MirSharifi | 62.5 | 2005-2006 | Tehran | Patients with severe peripheral vascular disease | 54 | 38.9 | 24 |

| [72]Forouzannia | 61 | 2008-2009 | Yazd | Coronary artery disease | 923 | 47.9 | 27.8 |

| [73]Shakeri Bavil | 58.2 | 2005-2009 | Tabriz | Patients with peripheral arterial disease | 95 | 6.3 | - |

| [21]Esteghamati | 62 | 2003-2005 | Tehran | Patients with unstable angina or myocardial infarction | 514 | 91 | 10.5 |

| [74]Shahsavari Esfahani | 60 (12.5) | 2012 | Jahrom | Cardiovascular | 2392 | 48.2 | 30 |

| [75]Jalali Farhani | - | 2007 | Tehran | - | 194 | 73.6 | - |

| [76]Maleki | 60.7 | 2009-2010 | Bojnord | - | 260 | 29 | 42.8 |

| [77]Jamshidi | - | 2013 | Hamedan | Cardiovascular | 550 | --- | 11 |

| [78]Akbari | 60.75 (9.78) | 2012 | Sari | Heart surgery patients | 250 | 38 | - |

| [79]Rahnavard | 58.25 | 1395 | Tehran | Congestive heart failure | 184 | 61.4 | 22 |

| [80]Hadian | 68 | 1987-88 | Sari | Heart failure | 140 | 22.9 | - |

| [81]Danesh sani | 66.15 (1.5) | 2000-2001 | Mashhad | Heart failure | 117 | 62 | - |

| [82]Ahmadi | - | 2014 | Heart failure | 1691 | 42.7 | 21 | |

| [83]Asgharzade Haghighi | 75.01 (6.20) | 2003-2008 | Karaj | Systolic Heart Failure | 154 | 42.2 | - |

| [84]Malak | - | 2002-2003 | Semnan | Heart failure | 248 | 32.2 | 31.1 |

| [85]Hasanzade | 58.6 (10.2) | 1998-2009 | Mashhad | Coronary artery disease | 1000 | 43.5 | - |

| [86]Imani poor | - | 2003-2004 | Tehran | Coronary artery disease | 93 | 54.8 | 31 |

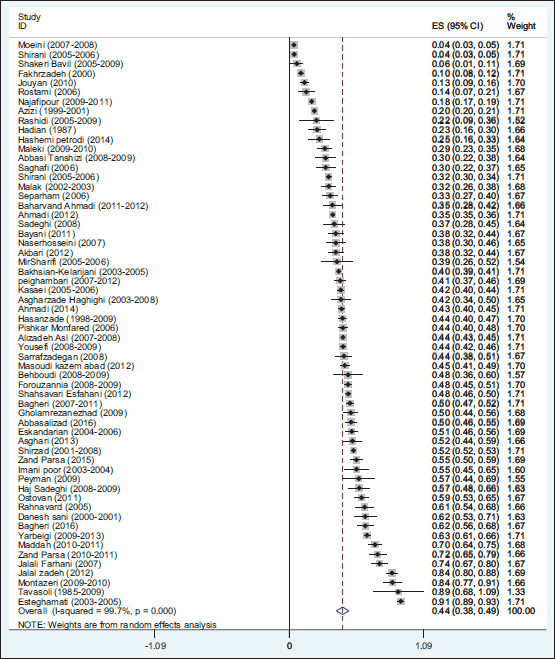

The prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran was 44% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 38%–49%) [Diagram 1]. The lowest and highest prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients were in the studies of Moeini (4%)[20] and Esteghamati (91%),[21] respectively.

Diagram 1.

The prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran and its 95% confidence interval based on the author's name and year of research according to the random effects model. The midpoint of each section shows the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in each study. The lozenge shows the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran for all studies

The prevalence of hypertension was 67% in women with cardiovascular disease (95% CI: 53%–82%) and 42% in men with cardiovascular disease (95% CI: 39%–46%).

In addition, the prevalence of systolic hypertension was 25% (95% CI: 12%–39%), the prevalence of diastolic hypertension was 20% (95% CI: 8%–31%), the prevalence of diabetes was 27% (95% CI: 23%–31%), the prevalence of overweight was 34% (95% CI: 18%–50%), and the prevalence of BMI was 33% (95% CI: 9%–57%) in cardiovascular patients [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of hypertension in patients with cardiovascular diseases in the studied subgroups

| Subgroups | Number of study | Sample size | Prevalence of hypertension (95% CI) | Minimum prevalence of hypertension (95% CI) | Maximum prevalence of hypertension (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of hypertension in women with cardiovascular diseases | 4 | 1996 | 67% (53%-82%) | 50% (47%-53%) | 76% (63%-89%) |

| Prevalence of hypertension in men with cardiovascular diseases | 4 | 2985 | 42% (38%-46%) | 39% (35%-43%) | 46% (43%-49%) |

| Prevalence of systolic hypertension in patients with cardiovascular diseases | 3 | 1326 | 25% (12%-39%) | 14% (10%-18%) | 38% (34%-42%) |

| Prevalence of diastolic hypertension in patients with cardiovascular diseases | 3 | 1326 | 20% (8%-31%) | 9% (6%-12%) | 28% (24%-32%) |

| Prevalence of diabetes in patients with cardiovascular diseases | 33 | 74251 | 27% (23%-31%) | 3% (3%-4%) | 58% (54%-63%) |

| Prevalence of overweight in patients with cardiovascular diseases | 4 | 17256 | 34% (18%-50%) | 18% (17%-19%) | 42% (38%-46%) |

The prevalence of hypertension was 44% in patients with CAD (95% CI: 37%–51%), 50% in patients with myocardial infarction (95% CI: 8%–93%), 33% in patients with aortic aneurysm (95% CI: 14%–52%), and 44% in patients with heart failure (95% CI: 34%–54%). The highest prevalence of hypertension was in patients with myocardial infarction.

In an analysis based on age group, the prevalence of hypertension was 14% in cardiovascular patients aged 40 to 49 years old (95% CI: 8%–20%), 46% in patients aged 50 to 59 years old (95% CI: 42%–49%), and 48% in patients aged 60 to 69 years old (95% CI: 37%–59%); there was only one study in the age group of 70 years old and above, and the prevalence of hypertension in other age groups was 39% (95% CI: 28%–50%). In fact, the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients has increased with increasing age.

In the analysis of the geographical regions, the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients was 49% in the north of Iran (95% CI: 42%–57%), 32% in the center (95% CI: 22%–42%), 33% in west (95% CI: 17%–49%), 43% in east (95% CI: 36%–49%), and 29% in the south (95% CI: 0%–67%) in just one study. The highest and lowest prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients was in the north and south of Iran, respectively.

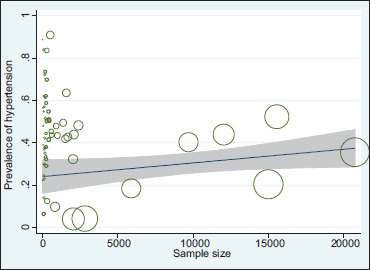

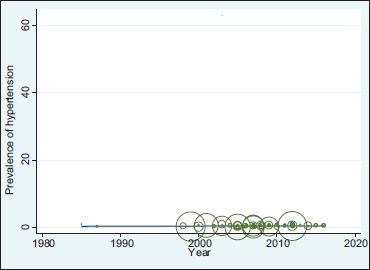

In Diagram 2, meta-regression showed no significant relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients and sample size (P = 0.271). In addition, there was no significant relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients and the year of study in Diagram 3 (P = 0.675).

Diagram 2.

Relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran and the research sample size using meta-regression

Diagram 3.

Relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran and the year of the study using meta-regression

Discussion

The prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran was 44%, which was 67% in women and 42% in men. Asmar et al. reported the prevalence of hypertension in French men and women to be 37.9 and 22.2, respectively.[87] In this study, the prevalence of hypertension in women was higher, which is consistent with the results of this study.

Across the WHO regions, the prevalence of raised blood pressure was highest in Africa, where it was 46% for both sexes combined. Both men and women have high rates of raised blood pressure in the Africa region, with prevalence rates over 40%. The lowest prevalence of raised blood pressure was in the WHO region of the Americas at 35% for both sexes. Men in this region had higher prevalence than women (39% for men and 32% for women). In all WHO regions, men have slightly higher prevalence of raised blood pressure than women. This difference was only statistically significant in the Americas and Europe.[88]

Several meta-analysis have been conducted on blood pressure in different countries, which we will mention later. Results from 23 analyses in 2016 were excluded from main analyses owing to high risks of confounding. Increased long-term variability in systolic blood pressure was associated with risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.09–1.22), cardiovascular disease mortality (1.18, 95% CI: 1.09–1.28), cardiovascular disease events (1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.30), coronary heart disease (1.10, 95% CI: 1.04–1.16), and stroke (1.15, 95% CI: 1.04–1.27). Increased mid-term and short-term variability in daytime systolic blood pressure were also associated with all-cause mortality (1.15, 95% CI: 1.06–1.26, and 1.10, 95% CI: 1.04–1.16, respectively).[89] In a research, 42 studies with 402,282 participants were included. We estimated prevalence of hypertension in Iran during 1980–2012 (I[2] = 99%). The overall pooled prevalence of hypertension was 22% (95% CI: 20.2–23.8). The prevalence of hypertension was 23.6% (95% CI: 21.1–26.1) in men and 23.5% (95% CI: 20.2–23.8) in women. In urban areas, the prevalence of hypertension was 22.1% (95% CI: 19.4–24.7(.[90] In this study, there was no difference in the prevalence of hypertension between men and women. In other research, from 100 articles in 2017 in Iran which were found in the searched references, 22 of them were finally analyzed. Among the selected final articles from 1999 to 2012, 96,689 participants participated in this study. The prevalence of hypertension was 17%. The prevalence rate of hypertension among the people aged above 20 years was between 10% and 32% and its mean was 24% (95% CI: 23%–24%).[91] As we see, the prevalence of hypertension in heart patients in Iran is higher than normal people, which is evident.

In a study, a total of 242 studies, comprising data on 1,494,609 adults from 45 countries, met our inclusion criteria. The overall prevalence of hypertension was 32.3% (95% CI: 29.4–35.3), with the Latin America and Caribbean region reporting the highest estimates (39.1%, 95% CI: 33.1–45.2).[92] In other research of a total of 1240 articles, 18 studies comprising 42,618 participants met the eligibility criteria. The overall pooled prevalence of hypertension in Pakistani adolescents was 26.34% (25.93%, 26.75%).[93] Prevalence of hypertension in Pakistani adolescents is lower than that of cardiovascular patients in Iran.

Overall prevalence of hypertension was 17%, with 21.4% in the urban population and 14.8% in the rural population.[94] Prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in India is lower than that of cardiovascular patients in Iran. Overall prevalence for hypertension in India was 29.8% (95% CI: 26.7–33.0).[95] Prevalence of hypertension in Indian populations is lower than that of cardiovascular patients in Iran. In 32 reviewed studies with a sample of 34,714 participants, the prevalence of hypertension in Iranian diabetic patients was 51% (95% CI: 43%–60%).[96] Therefore, the prevalence of hypertension in Iran is higher in patients with heart disease than in diabetic patients.

Meta-regression showed no significant relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients and the research sample size (P = 0.271); that is, in studies with larger sample sizes (larger circle), the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients increased, but this increase is not statistically significant [Diagram 2]. There was no significant relationship between the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients and the year of study (P = 0.675); according to Diagram 3, during the years 1985–2017, the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran was almost constant, but this is not statistically significant. Sensitivity analysis showed that the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients in Iran after omitting the study of Esteghamati[21] decreased to 42.66 (95% CI: 37.83%–47.50%), and after omitting the study of Moeini[20] increased to 44.18 (95% CI: 39.35%–49.01%), and these two studies are the most effective studies in the final meta-analysis.

According to a study, the prevalence of heart failure in England was 7.79%.[97] In a study among American people aged 18 to 74 years based on the definition of hypertension (hypertension over 140/90), the prevalence of hypertension was 29.2%.[98] In another study published by Vasan in Framingham in 2001, 14.7% of people with high blood pressure suffered from cardiovascular events over the course of 10 years.[99] In United States, 83.6 million people have at least one type of CAD. According to the International Center for Health Statistics, in 2012, 6.8% of people over the age of 18 in Asia had heart disease, 4.5% had CAD, and 21.2% had high blood pressure.[100] Studies in Spain show that the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure (37.6%) and diabetes (6.2%) is high.[101] In a study titled “Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children in the United States” by Barton et al., 22.3% of them had systolic and diastolic blood pressures above the 90th percentile.[102]

The limitations of the study include insufficient information in some articles, the lack of uniform distribution of studies in different regions of Iran, since only two studies were conducted in the south Iran; some studies were conducted on cardiovascular patients and healthy participants, and the prevalence of hypertension was not reported separately for each group.

The benefits of the study: This article, for the first time in Iran, studies the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients with a systematic and meta-analytic review. It also expresses the prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients, in terms of men and women, and the severity of systolic and diastolic hypertension.

Conclusions

The prevalence of hypertension in cardiovascular patients is high in Iran and is higher among women, and the problem increases with age. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction patients have the highest levels of hypertension. The prevalence of systolic blood pressure in cardiac patients is more than diastolic hypertension, and cardiac patients in the north of Iran are more likely to have hypertension than patients in other regions of Iran.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Motedayen M, Sarokhani D, Meysami A, Jouybari L, Sanagoo A. The prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients in Iran; a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephropathology. 2018;7:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Jivad N, Solati K. Effects of yoga on physiological indices, anxiety and social functioning in multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized trial. J Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR. 2016;10:VC01. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18204.7916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammadi N, HassanpourDehkordi A, NikbakhatNasrabadi A. Iranian patients with chronic hepatitis struggle to do self-care. Life Sci J. 2013;10:457–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: Comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87:235–41. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin YR, Lee IS, Lee HY. Effects of hypertension, diabetes, and/or cardiovascular disease on health-related quality of life in elderly Korean individuals: A population-based cross-sectional survey. Asian Nursing Res. 2014;8:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chobanian A, Bakris G, Black H, Cushman W, Green L, Izzo J, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines. 1999 World Health Organization. International society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999;17:151–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beygizadeh S, Zareei S, Pourahmadi M. The prevalence of hypertension and factors affecting it in Jahrom City. Pars J Med Sci (Jahrom Med J) 2009;7:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A metaanalysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirby M. NICE and hypertension. Sage. 2006;6:177–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naghavi M, Jafari N. Death Profile in 29 Province of Iran in 2005. Tehran: Iranian Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izumi Y, Matsumoto K, Ozawa Y, Kasamaki Y, Shinndo A, Ohta M, et al. Effect of age at menopause on blood pressure in postmenopausal women. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:1045–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. Hypertension epidemiology and economic burden: Refining risk assessment to lower costs. Manag Care. 2009;18:51–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karimloo M. Application of general linear models in blood pressure. Tehran Univ Med Sci. 1991;12:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alizadehasl A, Golmohammadi Z, Panjavi L, Mahmoodmoradi S, Azarfarin R. The incidence of anaemia in adult patients with cardiovascular diseases in northwest Iran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:1091–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadeghi M, Roohafza H, Sadry G, Bahonar A, Saeidi M, Asgari S, et al. Prevalence of high blood pressure and its relation with cardiovascular risk factors. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2003;26:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azizi A, Abasi M, Abdoli G. The prevalence of Hypertension and its Association with age, sex and BMI in a population being educated using community based medicine in Kermanshah. Iran J Endocrinol Metab (IJEM) 2008;10:323–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi A, Hasanzade J, Rajaei Fard A. The study of effective factors on hypertension in Koohrang city- Chaarmahal and Bakhtiyari province in 2007. Iran J Epidemiol. 2008;4:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodarzi M, Badakhsh M, Masinaei N, Abbas Zade M. Hypertension prevalence in over 18 years old. JIUMS. 2004;11:821–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moeini M, Mokhtari H, Adibi F, Lotfizadeh N, Moeini M. The prevalence of hypertension among the elderly in patients in Al-Zahra Hospital, Isfahan, Iran. ARYA Atheroscler. 2012;8:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esteghamati A, Abbasi M, Nakhjavani M, Yousefizadeh A, Amelita P, Afshar H. Prevalence of diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian population with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev J. 2015;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, Pocock S, Gøtzsche P, Vandenbroucke J. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Separham K, Shemirani H. Smoking or high blood pressure, which one is more important in premature coronary artery disease? J Isfahan Med Sch Spring. 2007;25:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavassoli A, Mirsaeid Ghazi S, Mirsaeid Ghazi A. Hypertension and cardiovascular manifestations in children and adolescents with secreting adrenal tumors. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;13:106–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghaeishahsavari M, Noroozianavval M, Veisi P, Parizad R, Samadikhah J. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with confirmed cardiovascular disease. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1358–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H, Mirmiran P, Hajipour R, Madjid M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study (phase 1) Soz Praventivmed. 2002;47:408–26. doi: 10.1007/s000380200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saghafi H, Mahmoodi M, Fakhrzadeh H, Heshmat R, Shafaee A, Larijani B. Cardiovascular risk factors in first-degree relatives of patients with premature coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol. 2006;61:607–13. doi: 10.2143/AC.61.6.2017959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghaffari S, Pourafkari L, Tajlil A, Bahmani Oskoui R, Nader N. Is female gender associated with worse outcome after ST elevation myocardial infarction? Indian Heart J. 2017;69:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirzad M, Karimi A, Dowlatshahi S, Ahmadi S, Davoodi S, Marzban M, et al. Relationship between body mass index and left main disease: The obesity paradox. Arch Med Res. 2009;40:618–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masoudi Kazemabad A, Jamialahmadi K, Moohebati M, Mojarrad M, Dehghan-Manshadi R, Forghanifard MM, et al. High frequency of Neuropeptide Y Leu7Pro polymorphism in an Iranian population and its association with coronary artery disease. Gene. 2012;496:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hajsadeghi S, Khamseh M, Larijani B, Abedin B, Vakili Zarch A, Meysamie A, et al. Bone mineral density and coronary atherosclerosis. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2011;23:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peyman H, Yaghoubi M, Zarei M, Dastgerdian F. Prevalence of anxiety disorder among cardiovascular patients in ilam province, western Iran. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbasalizad Farhangi M, AtaieJafari A, Najafi M, Sarami Foroushani G, Mohajeri Tehrani M, Jahangiry L. Gender differences in major dietary patterns and their relationship with cardio-metabolic risk factors in a year before coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery period. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:470–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baharvand Ahmadi B, Sharifi K, Namdari M. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with coronary artery disease. ARYA Atheroscler. 2016;12:201–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagheri B, Zargari M, Meshkini F, Dinarvand K, Mokhberi V, Azizi S, et al. Uric acid and coronary artery disease, two sides of a single coin: A determinant of antioxidant system or a factor in metabolic syndrome. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:27–31. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16335.7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rashidi I, Houshmand R. Prevalence, types and complications of aortic aneurysms during a five-year period in the health care centers of khuzestan, Iran. Int J Pharm Tech. 2016;8:11416–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zand Parsa A, Jahanshahi B. Is the relationship of body mass index to severity of coronary artery disease different from that of waist-to-hip ratio and severity of coronary artery disease? Cardiovasc J Afr. 2017;26:1–4. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2014-054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asghari E, Taban Sadeghi M, Parizad R, Mohammasdi Jhale N. Management of acute myocardial infarction and its effect on Women's health (Female versus Male) Int J Women's Health Reprod Sci Spring. 2014;2:207–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostovan M, Darvish N, Askarian M. The prevalence of risk factors of coronary artery disease in the patients who underwent coronary artery bypass graft, Shiraz, Iran: Suggesting a model. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:139–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montazeri M, Montazeri M, Rashidi N, Montazeri M, Montazeri M. Diagonal earlobe crease and coronary artery disease in Iranian population: A marker for evaluating coronary risk. Indian J Otol. 2014;20:208–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmadi A, Soori H, Sajjadi H, Nasri H, Mehrabi Y, Etemad K. Current status of the clinical epidemiology of myocardial infarction in men and women: A national cross-sectional study in iran? Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.151822. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.151822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashemi SMJ, Janbabai G, Hashemi Soteh SMB, Shekarriz R, Mahdavi MR, Ghaemian A, et al. Investigating factor V leiden and prothrombin G20210A gene mutation in relation with acute myocardial infarction. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalalzadeh M, Mousavinasab N, Soloki M, Miri R, Ghadiani M, Hadizadeh M. Association between metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrourol Mon. 2015;7:25560–8. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.25560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baharvand Ahmadi B, Pouria A. The prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with coronary artery disease, Lorestan province, Iran. Der Pharm Lett. 2015;7:446–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peighambari MM, Aryafar M, Mirmesdagh Y, Gholizadeh B, Hosseini S, Samiei N. Prevalence of atherosclerosis risk factors in patients with aortic stenosis. Iran Heart J. 2014;15:13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jouyan N, Saffari B, Davoudi Dehaghani E, Saliani N, Senemar S, Bahari M, et al. Association of usf1s2 variant in the upstream stimulatory factor 1 gene with premature coronary artery disease in southern population of Iran. Tehran Univ Med J. 2015;72:838–46. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jahangiri H, Norouzi AR, Dadsetan P, Sarabi G. Determine the prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors in depressed retired population. Life Sci J. 2013;10:327–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakhshian Kelarijani R, Moshkani Farahani M, Bahrami Ahmadi A. Risk factor profile and angiography findings in military and non-military patients with coronary artery disease. Iran Heart J. 2011;12:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbasi Tashnizi M, Zirak N, Heidari Bakavoli A, Tayyebi M, Moienpour A, Mirkazemi M. Atrial fibrillation after off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Iran Heart J. 2011;12:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pishkar Mofrad Z, Arbabi Sarjou A, Roudbari M, Sarani H, Hashemazahi M, Ebrahimtabass E. Coronary artery disease in critical patients of Iran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:1282–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Najafipour H, Nasri HR, Afshari M, Moazenzadeh M, Shokoohi M, Foroud A, et al. Hypertension: Diagnosis, control status and its predictors in general population aged between 15 and 75 years: A community-based study in southeastern Iran. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:999–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maddah M, Salari A, Momeni M. Iranian patients with coronary artery disease: Rural versus urban residents. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2013;6:269–71. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zandparsa A, Habashizadeh M, Moradi Farsani E, Jabbari M, Rezaei R. Relationship between renal artery stenosis and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with coronary atherosclerotic disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2012;6:84–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hosseini S, Tahvildari M, Alemzadeh Ansari M, Esteghamati AL, Lotfi Tokaldany M, Nakhjavani M. Clinical lipid control success rate before and after percutaneous coronary intervention in Iran; A single center study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:467–72. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagheri J, Sarzaeem M, Kord Valeshabad A, Bagheri A, Mandegar M. Effect of sex on early surgical outcomes of isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Turk Gogus Kalp Dama. 2014;22:534–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yaribeygi H, Taghipour H, Taghipour H. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients undergoing CABG Brief report. Tehran Univ Med J. 2014;72:570–4. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadeghi M, Heidari R, Mostanfar B, Tavassoli A, Roghani F, Yazdekhasti S. The relation between ankle-brachial index (ABI) and coronary artery disease severity and risk factors: An angiographic study. ARYA Atheroscler. 2011;7:68–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yousefi A, Madani M, Azimi H, Farshidi H. The factors relevant to the onset of vascular complications after coronary intervention in Shahid Rajaei Cardiovascular Center in Tehran, Iran. Tehran Univ Med J. 2011;69:445–50. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gholamrezanezhad A, Shirafkan A, Mirpour S, Rayatnavaz M, Alborzi A, Mogharrabi M, et al. Appropriateness of referrals for single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT-MPI) in a developing community: A comparison between 2005 and 2009 versions of ACCF/ASNC appropriateness criteria. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:1044–52. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rostami M, Mirmohammadsadeghi M, Zohrenia H. Evaluating the frequency of postoperative fever in patients with coronary artery bypass surgey. ARYA Atheroscler. 2011;7:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eskandarian R, Ghorbani R, Shiyasi M, Momeni B, Hajifathalian K, Madani M. Prognostic role of Helicobacter pylori infection in acute coronary syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23:131–5. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bayani B, Yousefi S, Bayani M, Shirmohammadi M, Alimoradi A, Falsoleiman H, et al. Depression and anxiety in a cardiovascular outpatient clinic: A descriptive study. Iran J Psychiatry. 2011;6:125–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shirani S, Shakiba M, Soleymanzadeh M, Bakhshandeh H, Esfandbod M. Ultrasonographic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in Iranian candidates for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:383–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shirani S, Shakiba M, Soleymanzadeh M, Bakhshandeh H, Esfandbod M. Ultrasonographic screening of the carotid artery in coronary artery bypass surgery. J Tehran Univ Heart Cent. 2009;4:181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fakhrzadeh H, Bandarian F, Adibi H, Samavat T, Malekafzali H, Hodjatzadeh E, et al. Coronary heart disease and associated risk factors in Qazvin: A population-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarrafzadegan N, Rezaporian P, Kaypour M, Mohseni M, Sadeghi M, Asgary S, et al. Prognostic value of infection and inflammation markers for late cardiac events in an Iranian sample. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:1246–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Behboudi F, Vakili H, Hashemi S, Hekmat M, Safi M, Namazi M. Immediate results and six-month clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with prior coronary artery bypass surgery. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2011;6:31–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nesar Hoseini V, Rasouli M. Microalbuminuria correlates with the prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease in non-diabetic patients. Cardiology J. 2009;16:142–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kassaei SA, Nozari Y. Rate of urgent coronary artery bypass grafting in elective. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) J Tehran Univ Heart Cent. 2008;3:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mirsharifi R, Karimian F, Farahmand MR, Aminian A. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in patients with severe peripheral vascular diseases. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14:117–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forouzan Nia SK, Hadadzadeh M, Mirhosseini S, Hosseini H, Abdollahi M, Yazdi M, et al. Risk factors of blood transfusion in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass. Tehran Univ Med J TUMS Publ. 2010;68:522–6. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shakeri Bavil A, Ghabili K, Daneshmand S, Nemati M, Shakeri Bavil M, Namdar H, et al. Prevalence of significant carotid artery stenosis in Iranian patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:629–32. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S23979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shahsavari Esfahani S, Nazari F, Karimyar Jahromi M, Sadeghi M. Epidemiologic study of hospitalized cardiovascular patients in Jahrom hospitals in 2012-2013. Iranian J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;2:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jalali Farhani A, Naseri M, Lal Dolat Abadi H, Arab Salmani I, Joneidi Jafari N, Teimuri M. A comparison of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in military and non-military patients who underwent angioplasty at Tehran Shahid Rajaee Hospital in the Baqiyatallah Hospitals. Mil Med. 2008;2:137–42. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maleki A, Miri M, Ghanavati R, Bayat M, Montazeri M, Rashidi N, et al. The prevalence of risk factors of coronary artery diseases in CCU ward. Nurs Dev Health. 2013;3:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jamshidi L, Seif A. Estimation of the prevalence and comparison of the risk factors of cardiovascular diseases related to metabolic syndrome and their comparison in women and men referring to the cardiology center of Hamadan, Iran, 2013. Q J Health Breeze. 2013;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Akbari H, Nikkhah A, Alizadeh A. Evaluation of acute renal failure and its associated factors in heart surgery patients in Fatima Zahra Hospital, Sari, 2012. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rahnavard Z, Zolfaghari M, Kazemnejad A, Hatamipour K. An investigation of quality of life and factors affecting it in the patients with congestive heart failure. Hayat. 2006;12:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hadian K, Mokhbery V. Assessment and identification of precipitating factors of heart failure in 140 patients in Imam Khomeini Hospital of Sari in 1997-1998. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 1999;9:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Danesh Sani S, Ghaderi F, Afzal Nia S. The prevalence and association of systolic and diastolic cardiac failure in patients with cardiac failure during acute pulmonary edema. J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2006;94:435–40. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahmadi A, Soori H, Mobasheri M, Etemad K, Khaledifar A. Heart failure, the outcomes, predictive and related factors in Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:180–8. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asgharzade Haghifgi S, Zeighami Mohamadi S. Evaluation of anemia prevalence in elderly patients with systolic heart failure in Alborz social security hospital in Karaj, Iran. Q J Nurs Midwifery Faculty. 2010;8:131–7. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malak M, Eskandarian R, Musavi S, Malak F, Babaei M, Jandaghi E, et al. Cardiac failure exacerbations in patients admitted to Fatemieh hospital in Semnan. Hormozgan Med J Spring. 2004;8:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hasanzadeh M, Sabzevari A, Vahedian M. Mortality and morbidity followed coronary artery bypass surgery. J Health Chimes. 2013;1:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Imanipour M, Bassampour S, Bahrani N. Preoperative variables associated with extubation time in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Hayat. 2006;12:5–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2008.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Asmar R, Vol S, Pannier B, Brisac A. High blood pressure and associated cardiovascular risk factors in France. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1727–32. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.WHO. Raised blood pressure. URL: https://wwwwhoint/gho/ncd/risk_factors/blood_pressure_prevalence_text/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stevens S, Wood S, Koshiaris C, Law K, Glasziou P, Stevens R, et al. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:i4098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mirzaei M, Moayedallaie S, Jabbari L, Mohammadi M. Prevalence of hypertension in Iran 1980–2012: A systematic review. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2016;11:159–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mohsenzadeh Y, Motedayen M, Hemmati F, Sayehmiri K, Sarokhani M, Sarokhani D. Investigating the prevalence rate of hypertension in Iranian men and women: A study of systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bas Res Med Sci. 2017;4:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sarki A, Nduka C, Stranges S, Kandala N, Uthman O. Prevalence of hypertension in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1959. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shah N, Shah Q, Shah A. The burden and high prevalence of hypertension in Pakistani adolescents: A meta-analysis of the published studies. Arch Public Health. 2018;76:20. doi: 10.1186/s13690-018-0265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bhadoria A, Kasar P, Toppo N, Bhadoria P, Pradhan S, Kabirpanthi V. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in Central India. J Family Community Med. 2014;21:29–38. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.128775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raghupathy A, Nanda KK, Hirab P, Hassana K, Oscar HF, Emanuele D, et al. Hypertension in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1170–7. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Motedayen M, Sarokhani D, Meysami A, Jouybari L, Sanagoo A, Hasanpour Dehkordi A. The prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients in Iran; A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephropathol. 2018;7:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brettell R, Soljak M, Cecil E, Cowie M, Tuppin P, Majeed A. Reducing heart failure admission rates in England 2004-2011 are not related to changes in primary care quality: National observational study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1335–42. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kaplan N. Clinical Hypertension. 5th ed. New York: Willim and Wilkins Company; 1990. pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vasan R. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham Heart Study: A cohort study. Lancet. 2001;325:1682–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leon A, Franklin B, Costa F, Balady GJ, Berra K, Stewart K, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2014;111:369–76. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151788.08740.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hwang Y, Jee J, Young Oh E, Choi Y, Lee M, Kim K, et al. Metabolic syndrome as a predictor of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes in Koreans. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barton A, Gilbert L, Baramee J, Granger T. Cardiovascular risk in hispanic and non- hispanic preschoolers. Nurs Res. 2006;55:172–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]