Abstract

Objective

Emerging evidence supports a role for epigenetic regulation in the pathogenesis of scleroderma (SSc). We aimed to assess the role of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a key epigenetic regulator, in fibroblast activation and fibrosis in SSc.

Methods

Dermal fibroblasts were isolated from patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) and from healthy controls. MeCP2 expression was measured by qPCR and western blot. Myofibroblast differentiation was evaluated by gel contraction assay in vitro. Fibroblast proliferation was analysed by ki67 immunofluorescence staining. A wound healing assay in vitro was used to determine fibroblast migration rates. RNA-seq was performed with and without MeCP2 knockdown in dcSSc to identify MeCP2-regulated genes. The expression of MeCP2 and its targets were modulated by siRNA or plasmid. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) using anti-MeCP2 antibody was performed to assess MeCP2 binding sites within MeCP2-regulated genes.

Results

Elevated expression of MeCP2 was detected in dcSSc fibroblasts compared with normal fibroblasts. Overexpressing MeCP2 in normal fibroblasts suppressed myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast proliferation and fibroblast migration. RNA-seq in MeCP2-deficient dcSSc fibroblasts identified MeCP2-regulated genes involved in fibrosis, including PLAU, NID2 and ADA. Plasminogen activator urokinase (PLAU) overexpression in dcSSc fibroblasts reduced myofibroblast differentiation and fibroblast migration, while nidogen-2 (NID2) knockdown promoted myofibroblast differentiation and fibroblast migration. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) depletion in dcSSc fibroblasts inhibited cell migration rates. Taken together, antifibrotic effects of MeCP2 were mediated, at least partly, through modulating PLAU, NID2 and ADA. ChIP-seq further showed that MeCP2 directly binds regulatory sequences in NID2 and PLAU gene loci.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates a novel role for MeCP2 in skin fibrosis and identifies MeCP2-regulated genes associated with fibroblast migration, myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix degradation, which can be potentially targeted for therapy in SSc.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma, SSc) is a rare autoimmune connective tissue disease characterised by complex interplays between vascular dysfunction, immunological abnormalities and fibrosis.1,2 Depending on the pattern of skin involvement, SSc is classified into two major subtypes: limited cutaneous SSc and diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc).3 Patients with dcSSc tend to have severe internal organ involvement, rapid disease development and worse prognosis.4 SSc has the highest mortality among rheumatic diseases as a consequence of progressive tissue fibrosis; however, effective antifibrotic therapies to prevent rapid disease progression or revert existing fibrosis are currently limited.5

Fibrosis, secondary to excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) components accumulation, replaces normal tissue architecture with dense and stiff connective tissue, then leads to organ failure in patients with SSc.6 Sustained fibroblast activation and differentiation into myofibroblasts, marked by increased α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression, greatly contributes to amplified fibrotic responses and pathological fibrosis. SSc fibroblasts explanted from SSc lesional skin biopsies demonstrate a persistent ‘SSc phenotype’ during their serial passage in vitro.1,6,7 They are characterised by an autocrine transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signalling loop to maintain the SSc phenotype.8 This provides the platform for our studies of SSc fibroblasts in vitro.

Recent attention has been focused on epigenetic mechanisms mediating fibroblast activation and fibrosis in SSc.9,10 Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), an epigenetic regulator binding to methylated DNA, was originally considered to repress transcription via its interactions with HDAC-Sin3 complex, but was later shown to function mainly as an activator by recruiting the transcription factor CREB1 at activated promoters.11 Thus, there are considerable complexities in the possible mechanisms by which MeCP2 might regulate gene expression. Emerging studies revealed that MeCP2 was involved in liver fibrosis12,13 and pulmonary fibrosis.14 In addition, MECP2 has been identified as a susceptibility gene associated with dcSSc,15 confirming our earlier observations identifying MECP2 as a genetic risk locus in autoimmunity.16-19

In the current study, we hypothesise that MeCP2 is involved in fibrosis in SSc by regulating fibrotic genes and altering fibroblast functions. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expression of MeCP2 in fibroblasts isolated from healthy controls or patients with dcSSc, and then probed the effects of MeCP2 on myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast proliferation and migration. Unbiased RNA-seq and ChIP-seq were used to identify genome-wide transcriptional targets of MeCP2, followed by bioinformatics analyses and functional validations of identified targets. Several novel MeCP2-regulated genes altering fibrotic properties and fibroblast functions in SSc were identified.

METHODS

Patients and controls

Patients with dcSSc and healthy controls were included in this study. All patients fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for SSc.20 The median age of patients with dcSSc is 54 years (range 25–81 years, n=24, including 19 women and 5 men), with median disease duration of 3 years. The median age of healthy individuals is 53.5 years (range 22–72 years, n=25, including 21 women and 4 men). All subjects included in this study signed a written informed consent approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan.

Cell culture

Two 4-mm-punch biopsies from clinically affected forearm skin were obtained from each patient, and the same area was biopsied in the controls. Dermal fibroblasts were isolated as previously described21 and were validated by immunofluorescence analyses with fibroblast markers (online supplementary figure S1). Briefly, following skin sample homogenisation, dermal fibroblasts were grown in 2.05 mM L-glutamine Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (Hyclone), with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells between the third and sixth passage were used in all experiments.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR

Total RNA from passage 3–6 dermal fibroblasts was isolated by the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep (Zymo Research). cDNA was prepared using verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-PCR used for quantification of the mRNA expression of genes was performed using their primers and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on ViiA V.7 Real-Time PCR System, using β-actin as an internal standard for normalisation. Duplicate measurements were performed for each sample. Primer sequences used in this study are available on request. Primers were purchased from Sigma or QIAGEN.

Western blot

Total cell extracts were prepared by scraping passage 3–6 fibroblasts into lysis buffer followed by centrifugation and protein measurement in supernatant using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 10 μg protein per sample was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. MeCP2 proteins were probed by anti-MeCP2 antibody (Cell Signaling). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or β-actin was detected by anti-GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling) or anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma Aldrich) as loading controls. Band quantification was calculated using GelQuant.NET (BiochemLab Solutions).

Gene overexpression experiments

A 0.05 μg MECP2 vector or 0.1 μg PLAU vector (OriGene; same amount of pCMV6-XL5 vector was used as control) was transfected into passage 3–6 normal or dcSSc fibroblasts using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 (for PLAU) or 72 hours (for MECP2) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Culture media were changed after 24 hours of transfection. Subsequent analyses for qPCR, gel contraction assay, wound healing migration assay or proliferation assay were performed.

Gene knockdown experiments

Passage 3–6 dcSSc dermal fibroblasts were transfected with MeCP2 small interference RNA (siRNA) or non-targeting siRNA according the manufacturer's protocols (Dharmacon). DcSSc fibroblasts were seeded at 70% confluence to 6-well or 12-well culture plates, then transfected with 150 nM (final concentration) non-targeting or MeCP2 siRNA with Transit-TKO transfection reagent (Mirus Bio) and incubated for 48 hours. Similarly, knockdown condition was optimised for AXL (75 nM), ANPEP (25 nM), NID2 (125 nM), adenosine deaminase (ADA) (100 nM), TNFA1P1 (50 nM) and NTN4 (150 nM) in passage 5–6 dcSSc fibroblasts (siRNA were all purchased from Dharmacon). All siRNA targets sequences are available on request.

Wound healing scratch assay

Scratch assay was performed to measure the effect of MeCP2 on dermal fibroblast migration.22 Fibroblasts passage 3-6 were seeded in 12-well plates to 70% confluence followed by siRNA knockdown or overexpression experiments described earlier. When they reached 95% confluence (48 hours post transfection), cells were scraped with a plastic 200 μL pipette tip then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice. Cells were then grown with 0.1% FBS cell culture medium to prevent cell proliferation. The created gaps were photographed by EVOS XL Core Cell Imaging System at 0, 24 and 48 hours after scraping. Wound repair ability was used to evaluate wound closure rate. Wound repair=100 (A – B)/A, where A is the average wound surface area at 0 hour and B is the average wound surface area at 24 hours or 48 hours. Wound surface area was measured by Image J.23

Collagen gel contraction assay

Passage 3–6 fibroblasts transfected with empty vectors/control siRNAs, or MECP2 plasmid, PLAU plasmid, or NID2 siRNAs for 48 hours, were suspended in culture media at 2×106 cells/mL. Collagen solution was made according to the cell contraction assay manual (Cell Biolabs), then a mixture of cells and collagen solution was prepared to include two parts of cell suspension and eight parts of cold collagen working solution. 0.5 mL/well of cell-collagen mixture was added into a 24-well plate. After collagen polymerisation, 1.0 mL culture medium was added atop each collagen gel lattice. Cultures were incubated for 2 days, then collagen gels were gently released from culture dishes to initiate contraction. Collagen gel contraction was monitored for 2 days. Surface area of contracted gels was measured using Image J.23 The ratio of gel surface area at 48 hours divided by gel surface area at 0 hour reflects fibroblast contractile ability.

Immunofluorescence staining

Ki67 staining was used to determine the effect of MeCP2 on fibroblast proliferation. Passage 3–6 transfected fibroblasts were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, permeabilised with ice cold methanol for 5 min at 4°C. Blocking was performed with 400 μL/well of 5% FBS plus 5% goat serum for 30 min at 37°C, followed by incubation with 200μL/well of anti-ki67 at a concentration of 1:1000 (Abcam) or IgG for 1 hour 15 min at 37°C, then washed twice with PBS. Incubation with 200 μL/well anti-rabbit fluorescent conjugated secondary antibody (5 μg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark was then performed. Fibroblasts were washed twice with PBS and coverslipped with mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Ki67 and DAPI immunofluorescence images were captured using an Olympus BX51\DP72 microscope. Ki67+ cells and total cells were counted by Image J.23 The ratio of ki67+ cell number to total cell number was used for comparing proliferation rates of fibroblasts with different treatments. Immunofluorescence staining of fibroblast markers protocol is documented in online supplementary text.

RNA sequencing

Total RNAs from passage 4–6 dcSSc fibroblasts transfected with MeCP2 siRNA or control siRNA were extracted using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research), and then were DNAse-treated using TURBO DNA-free Kit (Invitrogen) (all RIN values were >9.5). In total, 300 ng RNA were used to construct stranded mRNA-seq libraries with TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina), and then underwent 100 bp, single-end reads sequencing on Illumina Hi-Seq 2500 platform (~22M reads/sample, 10 samples per lane).

RNA-seq data analysis

Sequence reads were cleaned using trimmomatic (V.0.36),24 and then mapped to human reference genome GRCh38. p7 with STAR (V.2.5.2b).25 Raw read counts were obtained using featurecounts from Subread package (V.1.5.0p3),26 and annotated by human gencode V.25 with only uniquely aligned reads. Data normalisation and differential expression analysis (negative binomial Wald test) between MeCP2 knockdown and control groups were performed using DESeq2 (V.1.14.1)27 within R (V.3.3.2) with adjusted p value (Benjamini-Hochberg multiple test correction) threshold of 0.05. Default independent filtering was performed by DESeq2 package using the mean of normalised counts as a filter criterion.28 Genes not passing the filter threshold were assigned ‘NA’ as adjusted p values and were not included in subsequent analyses. Literature mining was used to identify genes associated with SSc (eg, genes associated with ECM remodelling, cell proliferation and migration).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed by iDeal ChIP-seq kit for Transcription Factors (Diagenode), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, passage 4–6 dermal fibroblasts from patients with dcSSc or healthy controls were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Glycine was added to quench fixation. Cells were lysed and then sonicated on Misonix ultrasonic liquid processor S-4000 for 15 cycles (30 s on/30 s off). MeCP2 antibody, previously used for ChIP-seq in olfactory epithelial tissue29 or rabbit IgG and pre-washed protein A-agarose beads, were mixed and then incubated for 4 hours at 4°C on a rotator. Then 250μL sheared chromatin was incubated with antibody-beads mixed solution at 4°C overnight under constant rotation. Also, 2.5 μL sheared chromatin was put aside as Input. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted from beads using an elution buffer at room temperature with 30 min rotation. Immunoprecipitated chromatin and input were incubated for 4 hours at 65°C to decrosslink chromatin, then DNA was purified using magnetic beads included with the kits. MeCP2 ChIP-seq and input DNA libraries were prepared by the Apollo 324 Next Generation Sample Preparation System with WaferGen reagents, then PCR amplified, cleaned up and sequenced with 50 bp, single-end reads on Illumina Hi-Seq 2500 platform (20 samples pooled together in three lanes).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Raw sequence reads were aligned to hg38 genome using Bowtie (V.2.2.4).30 Uniquely mapped reads were selected by filtering out alignments with mapping quality <23 and were used in subsequent analyses. Peak calling was performed using MACS (V.2.1.1),31 by default threshold (q-value <0.01). Peaks overlapping DAC Blacklisted Regions32 were removed. Peaks for nearest genes were annotated using Homer (V.4.9.1).33 Bigwig format pile-up files were generated from MACS outputs and visualised for signals on UCSC genome browser.

Statistical analysis

All data were derived from at least two independent experiments. The results were presented as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism V.7.03 (GraphPad Software). A Student’s t-test was used to evaluate two-group comparisons, with statistical significance set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

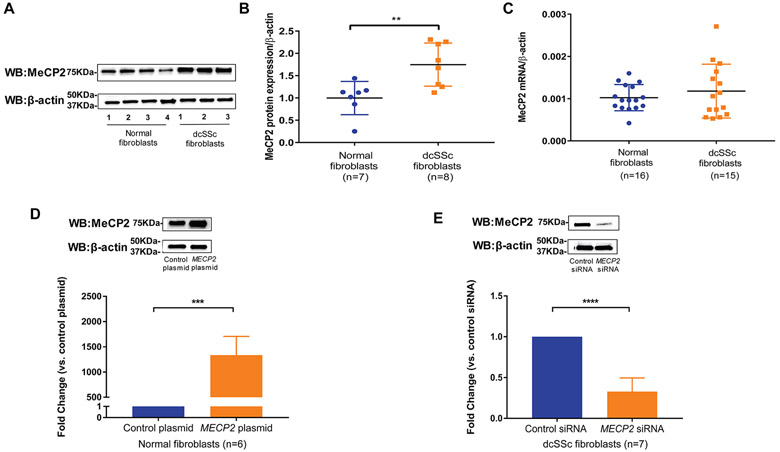

Elevated MeCP2 expression in dcSSc fibroblasts

We investigated MeCP2 expression in normal fibroblasts and dcSSc fibroblasts using qPCR and western blotting. MeCP2 expression was increased by 1.75-fold in dcSSc fibroblasts compared with normal fibroblasts at protein levels (figure 1A,B). However, no change was observed at the mRNA level for total MECP2 (figure 1C), MECP2A or MECP2B (online supplementary figure S2), suggesting that dysregulation of MeCP2 in dcSSc occurs at the post-transcriptional level. To assess effects of increased MeCP2 in dcSSc fibroblasts on skin fibrosis, we performed gain or loss of MeCP2 experiments. We first optimised conditions for overexpression or knockdown of MeCP2 in normal fibroblasts or dcSSc fibroblasts, respectively. As shown in figure 1D, transfection of 0.05μg MECP2 plasmid into normal fibroblasts for 72 hours led to overwhelming increase of MECP2 mRNA and 1.4-fold increase of MeCP2 protein level compared with negative controls. A 48-hour transfection of 150 nM MECP2 siRNA into dcSSc fibroblasts caused approximately 72% mRNA knockdown compared with non-targeting siRNA (figure 1E, lower panel). We further confirmed diminished MeCP2 expression at the protein level (figure 1E, upper panel). In subsequent experiments, we used 48-hour transfection of 150 nM MECP2 siRNA to knockdown MeCP2 in dcSSc fibroblasts and 72-hour transfection of 0.05μg MECP2 plasmid to overexpress MeCP2 in normal and dcSSc fibroblasts.

Figure 1.

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) was increased in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc) fibroblasts compared with normal fibroblasts. (A) Representative blots of MeCP2 expression in normal fibroblasts and dcSSc fibroblasts. (B) Protein expression of MeCP2 was significantly increased in dcSSc fibroblasts by 1.75-fold (p=0.0051). Values are the mean and SD from seven healthy controls and eight dcSSc patient fibroblasts. (C) Expression of MECP2 mRNA between normal fibroblasts (n=16) and dcSSc fibroblasts (n=15) was not significantly different. (D) 0.05 μg MECP2 plasmid transfection into normal fibroblasts for 72 hours successfully upregulated MeCP2 expression at both mRNA and protein levels compared with control plasmid. (E)150 nM MECP2 siRNA transfection in dcSSc fibroblasts for 48 hours resulted in an average of 72% mRNA knockdown. Diminished MeCP2 expression at the protein level was confirmed. Results are expressed as mean±SD. *p<0.05, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

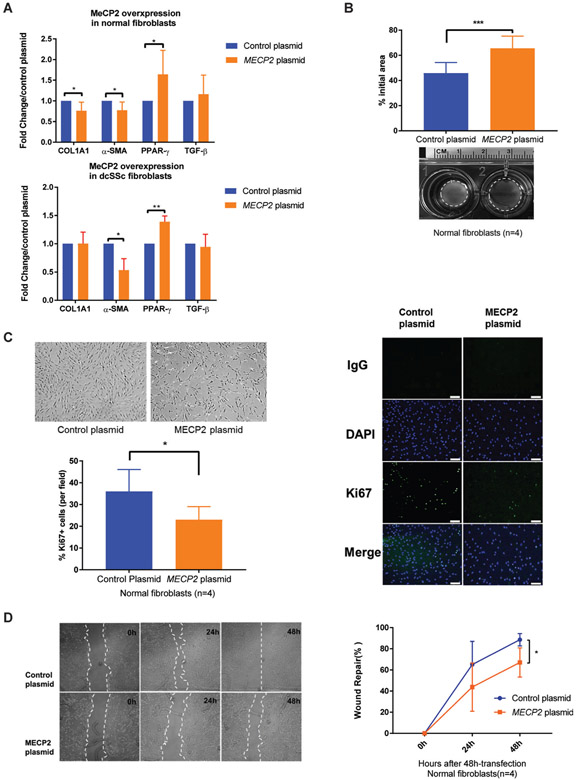

Reduced myofibroblast-like phenotype by MeCP2 overexpression

To investigate if increased expression of MeCP2 alters myofibroblast differentiation and fibrogenic properties in normal dermal fibroblasts, we overexpressed MeCP2 in normal dermal fibroblasts and measured expression levels of several well-characterised fibrogenic genes. MeCP2 overexpression significantly attenuated pro-fibrotic α-SMA and collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) mRNA expression in normal dermal fibroblasts, whereas antifibrotic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) was upregulated, and no effect was observed on TGF-β (figure 2A, upper panel). To confirm the results in dcSSc, we transfected dcSSc fibroblasts with MECP2 plasmid or MECP2 siRNA. A similar mRNA expression pattern was observed in MeCP2-overexpressing dcSSc fibroblasts (figure 2A, lower panel), indicating that reduced myofibroblast-like phenotype characteristics induced by MeCP2 overexpression is independent of stimuli secreted by dcSSc fibroblasts. Unexpectedly, mRNA expression of COL1A1, α-SMA and PPAR-γ was not significantly altered by MeCP2 knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts (data not shown), implying that other pro-fibrotic co-regulators exist for COL1A1, α-SMA and PPAR-γ.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) in fibroblasts inhibited myofibroblast differentiation, cell proliferation and migration rates. (A) Upper panel: overexpressing MeCP2 in normal fibroblasts reduced collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA expression (0.76±0.19-fold and 0.78±0.25-fold, respectively), while induced 1.50±0.23-fold increase in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) mRNA expression (n=6, p<0.05). Lower panel: overexpressing MeCP2 in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc) fibroblasts reduced α-SMA mRNA expression (0.53±0.28-fold, n=4, p=0.02), while induced 1.39±0.22-fold increase in PPAR-γ mRNA expression (n=4, p<0.01). Transforming growth factor (TGF-β) expression was not altered by MeCP2 overexpression. (B) MECP2-transfectd fibroblasts exhibited weaker contractile ability than empty vector transfected fibroblasts at 48 hours after gel stress was lifted (n=4, p<0.005). Representative images of contracted collagen gels are shown along with the quantification. (C) MECP2-transfected fibroblasts were noted to have decreased proliferation rates than negative controls. Quantification of ki67+ fibroblasts indicated that fibroblasts transfected with MECP2 plasmid exhibited attenuated proliferative capacity (n=4, p<0.01). Scale bar=100 μm. (D) MeCP2 overexpressing normal fibroblasts showed decreased cell migration rates at 0, 24 and 48 hours post scratch as quantified by wound repair (n=4, p<0.05). Results are expressed as mean ±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005. DAPI, ***4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

To provide more evidence that MeCP2 suppresses myofibroblast differentiation and functionally decreases contractile properties, we performed a collagen gel contraction assay. MeCP2 overexpression significantly reduced myofibroblast-mediated contraction of collagen gels compared with the control group. Representative images and quantified surface area of contracted gels are shown in figure 2B.

MeCP2 overexpression inhibits fibroblast proliferation and migration

We observed that MeCP2 overexpression in normal fibroblasts reduced cell proliferation rates compared with mock-transfected cells (figure 2C, upper-left panel). To validate and quantify this observation, proliferation analysis was performed using ki67 labelling (figure 2C, right panel). MeCP2-transfected fibroblasts showed a significantly reduced ki67-positive cell ratio compared with negative controls confirming decreased fibroblast proliferation with MeCP2 overexpression (figure 2C, lower-left panel).

Next, we conducted a wound scratch assay in vitro to determine if MeCP2 affects fibroblast migration. After 24 and 48 hours transfection, relatively less wound closure was seen in MeCP2 transfected normal fibroblasts compared with negative controls (figure 2D, left). Quantification of wound repair demonstrated that MeCP2 overexpressing fibroblasts had lower wound repair ability (figure 2D, right).

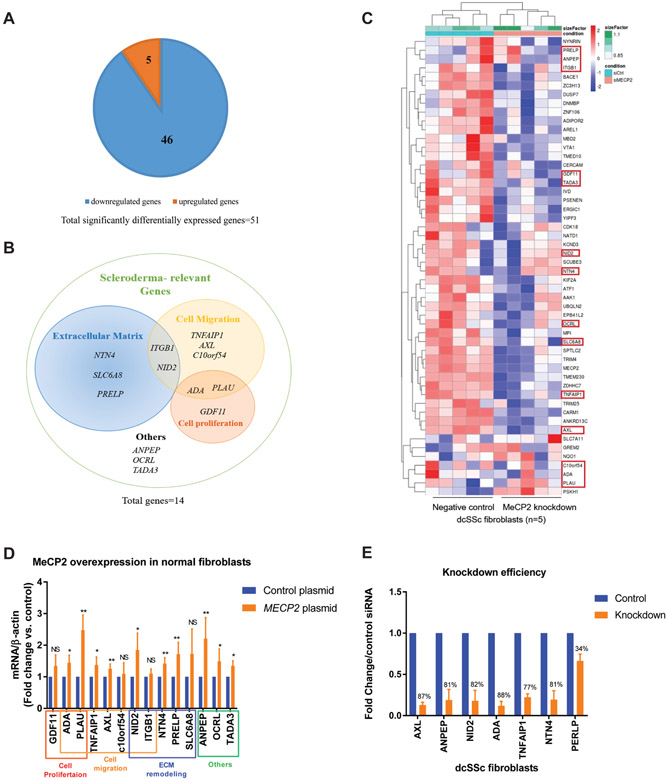

Transcriptome analysis of MeCP2-deficient dermal fibroblasts

The data above suggest that MeCP2 overexpression exerted antifibrotic effects in normal dermal fibroblasts by inhibiting myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast proliferation and fibroblast migration. To uncover antifibrotic mechanisms of MeCP2 in dcSSc fibroblasts, we examined genome-wide transcriptional changes in dcSSc fibroblasts with and without MeCP2 knockdown using RNA-seq. We identified 51 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), in addition to MECP2 downregulation as expected, with MeCP2 knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts (n=5, fold change ≥1.2 or≤0.8, adjusted p value<0.05) (figure 3A). Of those, 46 genes were downregulated with MeCP2 knockdown, indicating that MeCP2 primarily acts as a transcription activator in SSc fibroblasts, echoing the findings in other tissues indicating that MeCP2 activates the majority of genes it regulates.11

Figure 3.

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) depletion followed by RNA-seq identified targets important for extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling, cell migration and cell proliferation. (A) In total, 51 genes (in addition to MECP2) were significantly differentially expressed by MeCP2 knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts (46 downregulated and 5 upregulated). (B) Venn diagram depicting functional categories of 14 systemic sclerosis (SSc)-relevant genes identified by literature search. (C) All differentially expressed genes are shown in the heatmap, red circled genes are scleroderma-relevant genes. (D) mRNA expression of 14 SSc-relevant genes in MeCP2 overexpressing fibroblasts. Ten genes (ADA, PLAU, TNFAIP1, AXL, NID2, NTN4, PRELP, ANPEP, OCRL, TADA3) were significantly upregulated with MeCP2 overexpression. (E) Transfection of 75 nM AXL small interference RNA (siRNA), 25 nM ANPEP siRNA, 125 nM NID2 siRNA, 100 nM adenosine deaminase (ADA) siRNA, 50 nM TNFAIP1 siRNA and 150 nM NTN4 siRNA in dcSSc fibroblasts for 48 hours resulted in 87%, 81%, 82%, 88%, 77% and 81% knockdown efficiency compared with same amounts of control siRNAs, respectively. PERLP knockdown could not be achieved even with 250 nM siRNA and was excluded from subsequent functional assays. Results are expressed as mean±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005. NID2. nidogen-2; PLAU, plasminogen activator urokinase.

To identify MeCP2-regulated genes relevant to SSc, we first looked at functional annotations of all 51 DEGs using DAVID V.6.7, 34 then performed literature search for all DEGs using PubMed. Genes relevant to at least one of the following four categories were selected: genes that affect fibrotic signalling pathways, genes that affect ECM remodelling, genes that affect cell proliferation or migration and genes that have deregulated expression in fibrosis-involved diseases. Eventually, we identified 14 out of 51 DEGs to be relevant or potentially relevant to SSc, among which 5 downregulated genes (NTN4, SCL6A8, PRELP, ITGB1, NID2) were shown to be associated with ECM remodelling, 7 genes (TNFAIP1, AXL, C10or54, ITGB1, NID2, ADA, PLAU) were involved in cell adhesion/migration and 3 genes (ADA, PLAU and GDF11) were related to cell proliferation (figure 3B). Of note, 13 out of the 14 identified genes were downregulated with MeCP2 knockdown, while PLAU was upregulated (figure 3C).

We then confirmed that 9 out of 13 downregulated fibrosis-related genes identified by RNA-seq were indeed MeCP2-regulated genes as they were consistently upregulated when MeCP2 was overexpressed in normal fibroblasts (figure 3D). PLAU was upregulated when MeCP2 was either knocked down or overexpressed (figure 3C, D).

From these 10 MeCP2 potential targets, we excluded OCRL and TADA3 because their known functional roles (ie, apoptosis) in SSc were beyond the scope of our current studies in fibroblasts, then proceeded with the rest of the eight genes (ADA, PLAU, TNFAIP1, AXL, NID2, NTN4, PRELP, ANPEP) to further elucidate their roles in fibroblast functions according to their functional categories.

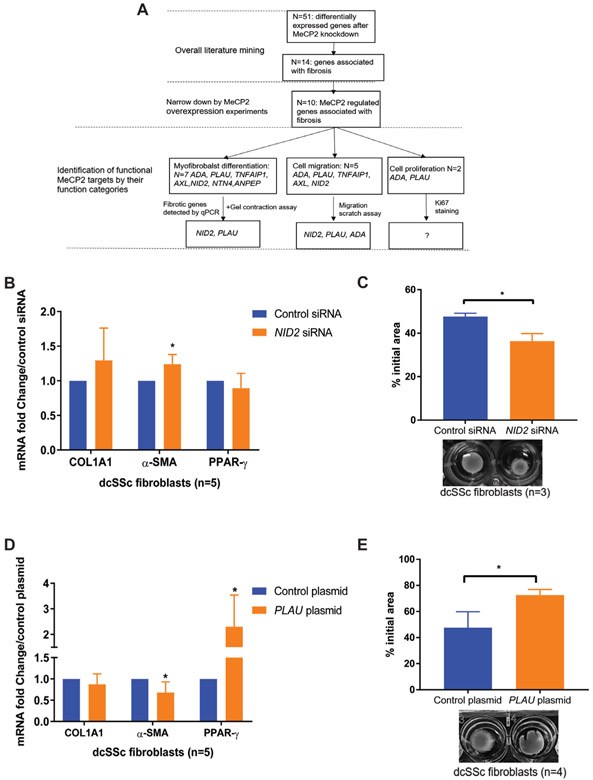

Identification of MeCP2 target genes that play functional roles in myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast migration and proliferation

We performed knockdown experiments for seven selected potential MeCP2 targets (ADA, TNFAIP1, AXL, NID2, NTN4, PRELP, ANPEP) and overexpression experiments for PLAU to determine their roles in dcSSc fibrosis individually. For knockdown experiments, at least an average 70% gene downregulation was reached for every potential target, with the exception of PRELP which we were unable to knockdown successfully and was therefore excluded from our functional studies (figure 3E).

Among all seven investigated potential MeCP2 targets, NID2 and PLAU were identified as pivotal genes in MeCP2-mediated myofibroblast differentiation (figure 4A). When NID2 was knocked down in dcSSc fibroblasts, the expression of α-SMA mRNA was moderately but significantly increased (figure 4B). In addition, NID2 knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts increased collagen gel contraction compared with control siRNA (figure 4C), suggesting NID2 knockdown stimulated myofibroblast differentiation. Similarly, overexpression of PLAU suppressed α-SMA mRNA expression, while increased PPAR-γ mRNA expression (figure 4D), and PLAU overexpressing fibroblasts exhibited weaker contractile ability than those transfected with empty vector (figure 4E). Taken together, our data suggest that NID2 and PLAU block myofibroblast formation, indicating that MeCP2-mediated inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation is, at least partly, mediated through activating NID2 and PLAU.

Figure 4.

Nidogen-2 (NID2) and plasminogen activator urokinase (PLAU) blocked myofibroblast formation. (A) A workflow illustrating bioinformatics analyses strategies for narrowing down genes involved in systemic sclerosis (SSc). (B) NID2 knockdown significantly increased (1.24±0.14-fold) α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA in diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) fibroblasts (n=5, p=0.020). (C) NID2-silenced dcSSc fibroblasts exhibited stronger contractile ability than empty vector transfected fibroblasts (n=3, p=0.021). Representative images of contracted collagen gels are shown along with the quantification. (D) Significantly decreased α-SMA mRNA expression (fold change=0.59 ± 0.22 vs control, n=5, p=0.021) and increased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) mRNA expression (fold change=2.26 ± 1.42 vs control, n=5, p=0.046) were detected in PLAU-overexpressing dcSSc fibroblasts. (E) PLAU overexpression significantly blocked myofibroblast-mediated contraction of collagen gels (n=4, p=0.029). Representative images of contracted collagen gels are shown along with the quantification. Results are expressed as mean ±SD. *p<0.05. COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1 chain; MeCP2, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2.

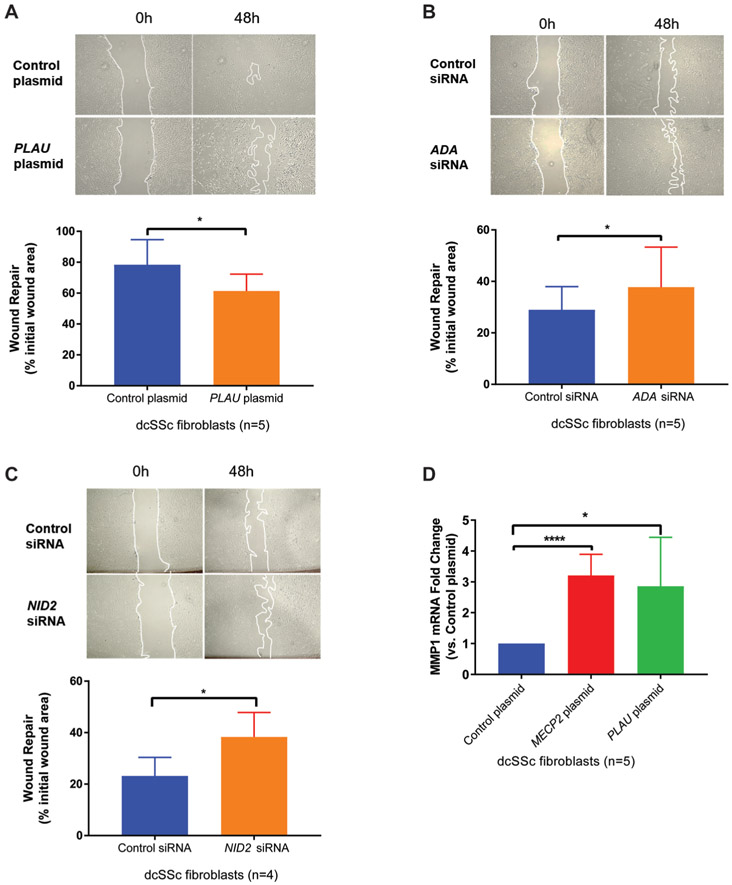

We next show that ADA, NID2 and PLAU are capable of inhibiting fibroblast migration. As shown in figure 5A, overexpressing PLAU suppressed dcSSc fibroblasts migration rates, while silencing ADA (figure 5B) and NID2 (figure 5C) significantly enhanced dcSSc fibroblast migration rates.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative images of wound closure with plasminogen activator urokinase (PLAU) overexpression in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc) fibroblasts at 0 and 48 hours post scratch. Quantification of wound healing migration assay suggested that PLAU overexpression delayed fibroblast migration (n=5, p=0.022). (B) Representative images of wound closure with adenosine deaminase (ADA) knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts at 0 and 48 hours post scratch. Quantification of wound healing migration assay suggested that ADA knockdown increased fibroblast migration (n=5, p=0.044) (C) Representative images of wound closure with nidogen-2 (NID2) knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts at 0 and 48 hours post scratch. Quantification of wound healing migration assay suggested that NID2 knockdown induced higher fibroblast migration rates (n=4, p=0.043). (D) Overexpression of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) caused 3.20±0.30-fold increase of MMP1 mRNA expression compared with control plasmid (n=5, p<0.001). Overexpression of PLAU caused 2.86±0.71-fold increase in MMP1 mRNA expression compared with control plasmid (n=5, p=0.030). Results are expressed as mean±SD. *p<0.05, ****p<0.001.

We could not identify genes mediating the fibroblast proliferation effect of MeCP2 in two cell proliferation-related MeCP2 targets. Overexpressing PLAU did not change proliferation of fibroblasts (data not shown). We could not assess cell proliferation effect of ADA because fibroblasts detached from the culture chamber used for ki67 staining and died after 24-hour ADA knockdown.

Potential ECM degradation by MeCP2-mediated PLAU activation

Since PLAU was upregulated with MeCP2 overexpression, we hypothesised that MeCP2 prevents ECM turnover through positively regulating PLAU and MMPs in dcSSc fibroblasts. As expected, MeCP2 overexpression significantly increased MMP1 mRNA (figure 5D). In addition, we show that PLAU overexpression in dcSSc fibroblasts was able to increase MMP1 mRNA expression (figure 5D). Collectively, these data indicate that MeCP2 could promote ECM degradation by overexpressing PLAU and PLAU-mediated MMP1.

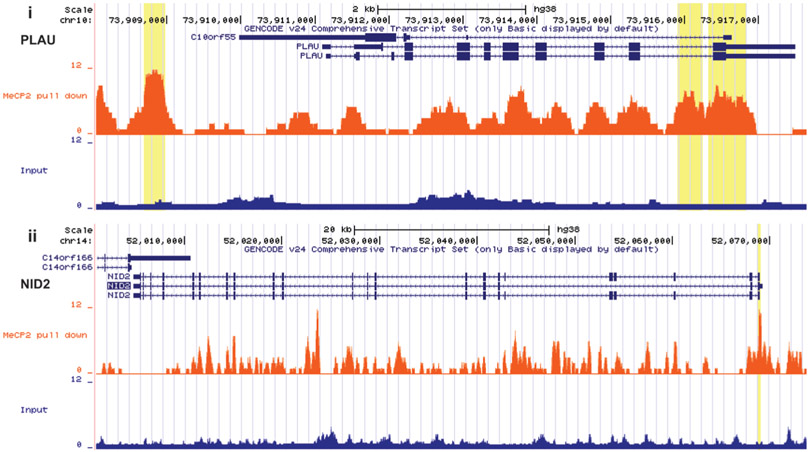

MeCP2 binding is enriched at NID2 and PLAU in dermal fibroblasts

To determine if the identified MeCP2-regulated genes in dermal fibroblasts are directly regulated by MeCP2, we mapped genome-wide MeCP2 binding sites in a dermal fibroblast sample from a healthy control. Possible chromatin-shearing biases were controlled by Input library from the same chromatin sample used for MeCP2 bound DNA pulldown. Significant peaks can be visualized in NID2 and PLAU on UCSC genome browser (figure 6), suggesting MeCP2 directly regulates NID2 and PLAU. Indeed, 6 out of 10 relevant MeCP2 target genes we identified in fibroblasts show significant MeCP2 binding enrichments (online supplementary table 1).

Figure 6.

Genome browser tracks show MeCP2 binding peaks in normal fibroblasts (orange) in PLAU (i) and NID2 (ii). Significant peak regions relative to input control (blue) are highlighted in yellow. NID2, nidogen-2; PLAU, plasminogen activator urokinase.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we clearly show MeCP2 as a novel antifibrotic epigenetic regulator in dcSSc. MeCP2, which was elevated in dcSSc fibroblasts, has inhibitory effects on myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast migration and fibroblast proliferation. Non-biased RNA-seq was employed to evaluate transcription alterations after MeCP2 knockdown in dcSSc fibroblasts, and a set of genes dysregulated by MeCP2 and related to fibrosis were identified. RNA profiles from fibroblasts after MeCP2 overexpression and depletion indicated that MeCP2 not only modulates well-known fibrosis-related genes, like COL1A1, α-SMA and PPAR-γ, but also targeted additional genes participating in myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast migration and fibroblast proliferation. NID2, PLAU and ADA were shown to be antifibrotic mediators of MeCP2 through functional studies.

In agreement with findings reported by Wang et al,35 we demonstrated that MeCP2 was significantly elevated in dcSSc fibroblasts compared with normal fibroblasts. Recent observations of the role MeCP2 in fibrosis were reported in hepatic stellate cells and lung fibroblasts derived from animal models with chronic CCl4-induced liver injury12 and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis14, respectively. Our studies are the first to report the role of MeCP2 in fibrosis in human dermal fibroblasts from patients with dcSSc. Interestingly, the data generated from animal models showed that MeCP2 upregulated α-SMA expression in lung fibroblasts14 and decreased PPAR-γ in a liver fibrosis animal model.12 Our data in human dcSSc fibroblasts indicate that MeCP2 attenuates pro-fibrotic responses, and that MeCP2 overexpression alters biological functions important in fibrosis, through antifibrotic MeCP2 target genes we identified and validated using functional studies. Therefore, our data suggest that increased MeCP2 in dcSSc fibroblasts might be a defence mechanism to counteract the pro-fibrotic nature of the disease in the early stages of dcSSc. COL1A1, α-SMA and PPAR-γ were responsive to MeCP2 regulation in normal fibroblasts, but they might also be co-regulated by other pro-fibrotic factors (eg, TGF-β), which exert prominent influence on dcSSc fibroblasts to maintain the ‘SSc phenotype’ compared with normal fibroblasts. COL1A1 expression was attenuated with MeCP2 overexpression in normal fibroblasts but not in dcSSc fibroblasts, indicating that the effects of MeCP2 on COL1A1 might be neutralised by other pro-fibrotic regulators amplified in dcSSc fibroblasts. A reduction in α-SMA and increase of PPAR-γ expression were observed with MeCP2 overexpression. Neither was significantly altered after MeCP2 knockdown. Plasminogen activator urokinase (PLAU), an antifibrotic enzyme dampening α-SMA mRNA levels and stimulating PPAR-γ mRNA expression in dcSSc fibroblasts, was upregulated both with MeCP2 overexpression and knockdown. Therefore, we postulate that PLAU activation in MeCP2-deficient fibroblasts may antagonise effects of MeCP2 knockdown on α-SMA and PPAR-γ gene expression.

By coupling RNA-seq with functional assays, not only were fibrotic genes like COL1A1, α-SMA and PPAR-γ confirmed as MeCP2-regulated genes, but also novel targets like PLAU, NID2 and ADA were identified as potential mediators in the antifibrotic effects of MeCP2. PLAU encodes a secreted serine protease urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) that converts plasminogen to plasmin, which is the important component of the extracellular protease system.36 Plasmin was linked to antifibrotic properties by directly degrading ECM proteins, such as fibronectin,37 and also activating MMPs that degrade the ECM proteins. In addition, PLAU plays a pivotal role in the cell migration and proliferation via direct binding to its receptor PLAUR or indirect binding to α–8/ β–1 integrin.38,39 Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, an inhibitor of uPA, mediates a variety of functions involved in fibrosis of different organs including lung, liver, kidney, as well as cardiovascular system.40,41 In our study, PLAU overexpression reduced pro-fibrotic properties, including downregulation of COL1A1 and α-SMA, upregulation of PPAR-γ and MMP1, and resulted in inhibitory effects on myofibroblast differentiation and cell migration in dcSSc fibroblasts. Urokinase is used as a thrombolytic agent and a possible therapeutic role in SSc is suggested by our findings, indicating a possible protective effect of PLAU in SSc fibrosis.

Nidogen-2 (NID2) encodes a secretory protein also known as osteonidogen, which is one of the key components of the basement membrane that stabilises the ECM network.42,43 It is a cell-adhesion molecule that binds collagens I and IV and laminin and may be involved in maintaining the structure of the basement membrane.44 In our study, NID2-depleted dcSSc fibroblasts exhibit increased α-SMA expression, contractility and migration ability, suggesting that NID2, a direct MeCP2 target, plays antifibrotic roles in dcSSc fibroblasts. Further experiments to understand the mechanisms of how these functions were modulated are warranted.

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) regulates levels of adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine in tissues and cells.45 ADA binds to the cell surface by means of either CD26, or adenosine receptors A1 or A2B.46 Some studies demonstrated that adenosine and its receptors may promote fibrosis in skin and liver fibrosis models, but inhibit fibrosis in cardiac tissues.47-49 In addition, lower serum level of ADA was reported in patients with cystic fibrosis.50 Mice lacking ADA accumulated 10-fold higher adenosine levels and underwent diffuse dermal fibrosis.48,49 Although we did not detect a change in collagen production after ADA knockdown, our data suggest a complementary antifibrotic role of ADA, as ADA silencing in dermal dcSSc fibroblasts promoted fibroblast migration. Pegademase bovine is the enzyme replacement drug in ADA-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency disease.51 Explorations unravelling mechanisms and the therapeutic effect of pegademase bovine in SSc would be of interest.

Limitations of our study include a focus on dermal fibroblasts isolated from patients with dcSSc and healthy controls, and therefore, whether MeCP2 dysregulation also plays a role in lung fibroblasts or other cell types involved in the pathogenesis of SSc, such as endothelial cells or immune cells, remains unknown. In addition, our studies were limited to in vitro experiments, and validation in in vivo models of fibrosis are warranted.

In summary, our results collectively imply that MeCP2 overexpression acts as protective mechanism against skin fibrosis in early dcSSc and that exploiting this mechanism might provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention in this disease. Several canonical and novel fibrotic genes regulated by MeCP2 were identified and functionally characterised. Drugs or compounds modulating MeCP2 expression or targeting these MeCP2-regulated genes might provide attractive new strategies to prevent the progression of fibrosis in scleroderma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health grant number R01AI097134 to Dr Sawalha. Dr Khanna is supported by NIH (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) grant number K24AR063120.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. Clin Invest 2007;117:557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017;390:1685–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wirz EG, Jaeger VK, Allanore Y, et al. Incidence and predictors of cutaneous manifestations during the early course of systemic sclerosis: a 10-year longitudinal study from the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1989–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1809–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Varga J. Understanding fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: shifting paradigms, emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011. ;8:42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbloom J, Castro SV, Jimenez SA. Narrative review: fibrotic diseases: cellular and molecular mechanisms and novel therapies. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ihn H, Yamane K, Kubo M, et al. Blockade of endogenous transforming growth factor beta signaling prevents up-regulated collagen synthesis in scleroderma fibroblasts: association with increased expression of transforming growth factor beta receptors. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altorok N, Kahaleh B. Epigenetics and systemic sclerosis. Semin Immunopathol 2015;37:453–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsou PS, Sawalha AH. Unfolding the pathogenesis of scleroderma through genomics and epigenomics. J Autoimmun 2017;83:73–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 2008;320:1224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann J, Chu DC, Maxwell A, et al. MeCP2 controls an epigenetic pathway that promotes myofibroblast transdifferentiation and fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2010;138:705–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bian EB, Huang C, Wang H, et al. The role of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 in liver fibrosis. Toxicology 2013;309:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu B, Gharaee-Kermani M, Wu Z, et al. Essential role of MeCP2 in the regulation of myofibroblast differentiation during pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2011;178:1500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmona FD, Cénit MC, Diaz-Gallo LM, et al. New insight on the Xq28 association with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:2032–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawalha AH, Webb R, Han S, et al. Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One 2008;3:e1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb R, Wren JD, Jeffries M, et al. Variants within MECP2, a key transcription regulator, are associated with increased susceptibility to lupus and differential gene expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1076–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koelsch KA, Webb R, Jeffries M, et al. Functional characterization of the MECP2/IRAK1 lupus risk haplotype in human T cells and a human MECP2 transgenic mouse. J Autoimmun 2013;41:168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawalha AH. Overexpression of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 and autoimmunity: evidence from MECP2 duplication syndrome, lupus, MECP2 transgenic and Mecp2 deficient mice. Lupus 2013;22:870–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altorok N, Tsou PS, Coit P, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in dermal fibroblasts from patients with diffuse and limited systemic sclerosis reveals common and subset-specific DNA methylation aberrancies. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1612–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc 2007;2:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017;18:529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014;30:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bourgon R, Gentleman R, Huber W. Independent filtering increases detection power for high-throughput experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:9546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rube HT, Lee W, Hejna M, et al. Sequence features accurately predict genome-wide MeCP2 binding in vivo. Nat Commun 2016;7:11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012;9:357–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 2008;9:R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012;489:57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 2010;38:576–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang daW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Fan PS, Kahaleh B. Association between enhanced type I collagen expression and epigenetic repression of the FLI1 gene in scleroderma fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myöhänen H, Vaheri A. Regulation and interactions in the activation of cell-associated plasminogen. Cell Mol Life Sci 2004;61:2840–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnefoy A, Legrand C. Proteolysis of subendothelial adhesive glycoproteins (fibronectin, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor) by plasmin, leukocyte cathepsin G, and elastase. Thromb Res 2000;98:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blasi F, Sidenius N. The urokinase receptor: focused cell surface proteolysis, cell adhesion and signaling. FEBS Lett 2010;584:1923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith HW, Marshall CJ. Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010;11:23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu F, Lagares D, Choi KM, et al. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015;308:L344–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flevaris P, Vaughan D. The Role of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor Type-1 in Fibrosis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2017;43:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohfeldt E, Sasaki T, Göhring W, et al. Nidogen-2: a new basement membrane protein with diverse binding properties. J Mol Biol 1998;282:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miosge N, Holzhausen S, Zelent C, et al. Nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 are found in basement membranes during human embryonic development. Histochem J 2001;33:523–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox JW, Mayer U, Nischt R, et al. Recombinant nidogen consists of three globular domains and mediates binding of laminin to collagen type IV.Embo J 1991;10:3137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cristalli G, Costanzi S, Lambertucci C, et al. Adenosine deaminase: functional implications and different classes of inhibitors. Med Res Rev 2001;21:105–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pacheco R, Martinez-Navio JM, Lejeune M, et al. CD26, adenosine deaminase, and adenosine receptors mediate costimulatory signals in the immunological synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:9583–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chunn JL, Mohsenin A, Young HW, et al. Partially adenosine deaminase-deficient mice develop pulmonary fibrosis in association with adenosine elevations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cronstein BN. Adenosine receptors and fibrosis: a translational review. F1000 Biol Rep 2011;3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan ES, Fernandez P, Merchant AA, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors in diffuse dermal fibrosis: pathogenic role in human dermal fibroblasts and in a murine model of scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2632–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farahmand F, Tajdini P, Falahi G, et al. Evaluation of Serum Adenosine Deaminase in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in an Iranian Referral Hospital. Iran J Pediatr 2016;26:e2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Booth C, Gaspar HB. Pegademase bovine (PEG-ADA) for the treatment of infants and children with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Biologics 2009;3:349–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.