Abstract

Despite the negative health consequences associated with smoking, most smokers find it difficult to quit. This is especially true for smokers with elevated social anxiety. One factor that may play a role in maintaining smoking with elevated anxiety is false safety behavior (FSB), behaviors geared toward decreasing anxiety short-term but that maintain or increase anxiety long-term. The present study tested whether FSB explained the relation of social anxiety severity with smoking among 71 current smokers. Avoidance-related FSB was the only type of FSB related to cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and it was robustly related to more CPD. Further, social anxiety was related to CPD indirectly via FSB-Avoidance. Findings suggest that more frequent use of avoidance behaviors to manage anxiety may maintain smoking and may partially explain the high rates of smoking among those with elevated social anxiety. Thus, FSB may be a promising target in smoking cessation interventions, especially among those with elevated social anxiety.

Keywords: anxiety, smokers, cigarettes, avoidance

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of death and disability in the United States (U.S.), contributing to over 440,000 deaths each year (National Center for Health Statistics, 2004). Over 40% of the 48 million Americans make a serious cessation attempt each year, but less than 5% of them quit (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2002). The health risks of smoking increase significantly with duration and amount smoked per day (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1988).

Consistent with the often ‘social nature’ of smoking, social anxiety is positively related to poorer smoking outcomes; yet, little attention has been paid to the relation between smoking and social anxiety. To illustrate, socially anxious smokers are more likely to be daily smokers than less socially anxious smokers (Buckner & Vinci, 2013) and those with social anxiety disorder (SAD) demonstrate greater likelihood of nicotine dependence and heavy smoking compared to individuals without SAD (Cougle, Zvolensky, Fitch, & Sachs-Ericsson, 2010). In fact, in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, over half of persons with SAD used nicotine and one-third suffer from nicotine dependence (Grant et al., 2005). Among treatment-seeking smokers, those with SAD report greater nicotine dependence (Piper, Cook, Schlam, Jorenby, & Baker, 2011) and SAD is associated with a greater number of failed quit attempts (Cougle et al., 2010). Social anxiety appears to be a risk factor for nicotine dependence (Sonntag, Wittchen, Höfler, Kessler, & Stein, 2000), although there may also be a reciprocal relation between social anxiety and nicotine dependence given that smoking is associated with a greater risk of subsequently developing SAD (Mojtabai & Crum, 2013). Notably, even subclinical social anxiety is prospectively related to more severe nicotine dependence (Sonntag et al., 2000). Further, social anxiety remains related to negative smoking outcomes after controlling for other relevant factors (e.g., depression, other anxiety conditions, other substance use disorder; Cougle et al., 2010; Sonntag et al., 2000).

Negative affect (NA) and maladaptive attempts to manage NA (e.g., smoking to manage affect rather than using more adaptive strategies) appear implicated in this relation. For example, among treatment-seeking smokers, social anxiety was robustly related to NA reduction expectancies for smoking (Buckner, Zvolensky, Jeffries, & Schmidt, 2014) and indirectly related to severity of nicotine dependence via NA reduction expectancies (Buckner, Farris, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2014). Additionally, social anxiety was related to more smoking to cope and greater number of cigarettes than participants estimated they would need to smoke to feel comfortable in social situations (N. L. Watson, VanderVeen, Cohen, DeMarree, & Morrell, 2012).

False safety behaviors (FSB) are behaviors used to decrease anxiety in response to phobic stimuli (i.e., false threats) and are highly utilized by individuals across anxiety conditions because they often temporarily alleviate anxiety (e.g., avoiding a situation that engenders fear; Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, & Preston, 2012). Yet, repeated use of such behaviors can contribute to the maintenance of heightened anxiety symptoms (Hope, Durrheim, d’Espaignet, & Dalton, 2006; Salkovskis, Clark, & Hackmann, 1991) due to failure to obtain evidence to disconfirm maladaptive beliefs about the actual danger posed by phobic stimuli (see Foa & Kozak, 1986). FSB is associated with, but distinct from, other anxiety-related constructs (e.g., worry, panic, social anxiety; Buckner, Zvolensky, Ecker, et al., 2017). The use of FSB among socially anxious individuals is related to greater anxiety (Clark & Wells, 1995; Piccirillo, Dryman, & Heimberg, 2016), poorer performance (Piccirillo et al., 2016), less favorable evaluation from others (Piccirillo et al., 2016), less desire for future social interaction by others (Piccirillo et al., 2016), and diminished treatment effects (Clark & Wells, 1995; Piccirillo et al., 2016). Thus, socially anxious smokers may be vulnerable to engaging in maladaptive attempts to manage NA that include, but are not limited to, smoking to manage affect. Reliance on such strategies at the exclusion of more adaptive coping strategies may increase their vulnerability to smoking and other negative smoking-related outcomes. Although no studies have tested the relation of FSB in the social anxiety-smoking link, indirect evidence highlights that FSB may play an important role. First, smokers report smoking to cope with NA (e.g., Battista et al., 2008; Buckner, Farris, et al., 2014; Leyro, Zvolensky, Vujanovic, & Bernstein, 2008; Zvolensky, Bonn-Miller, Bernstein, & Marshall, 2006). Second, FSB is robustly related to other substance variables (cannabis-related problems; Buckner, Zvolensky, Businelle, & Gallagher, 2017). Third, anxiety symptom severity is indirectly (via FSB frequency) related to severity of other substance use outcomes (cannabis problem severity; Buckner, Zvolensky, Ecker, et al., 2017).

The current study tested whether FSB would be related to greater smoking among smokers generally (regardless of social anxiety). Additionally, we tested whether FSB would be related to smoking after controlling for social anxiety, depression, and other relevant variables. Finally, we tested whether social anxiety would be indirectly related to greater smoking via FSB. Hypotheses were tested in a non-treatment-seeking sample of undergraduates given that most smokers do not seek smoking cessation treatment (Fiore et al., 1990; Hughes, Marcy, & Naud, 2009) and smoking rates tend to peak at this age (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2017).

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited through the psychology participant pool from Louisiana State University. Of the 1,059 students who completed study questions, 72 endorsed smoking. Of those, 1 was excluded for possibly invalid responses (described below). The final sample of 71 was predominately female (73.2%), with a mean age of 20.17, and the racial/ethnic composition was 2.8% non-Hispanic African American, 2.8% American Indian/Native American, 2.8% Asian American, 2.8% Hispanic Caucasian, 87.3% Non-Hispanic Caucasian, and 1.4% multiracial. Mean number of cigarettes per day (CPD) was 3.3 (SD = 4.6); among daily smokers (66.2%), the mean CPD was 5.0 (SD = 4.9). Nearly half (46.5%) endorsed past-month cannabis use and 25.4% endorsed clinically elevated social anxiety using an empirically supported clinical cut-score (34; Heimberg, Mueller, Holt, Hope, & Liebowitz, 1992) on the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (Mattick & Clarke, 1998).

The current study is a secondary analysis of a larger study on college substance use (e.g., Buckner, Lemke, & Walukevich, 2017). The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study and participants provided informed consent prior to data collection. Participants completed measures using surveymonkey.com and received research credit for study completion.

Measures

The Safety Aid Scale (SAS; Korte & Schmidt, 2014) assessed use of FSB while feeling nervous/anxious on a Likert-type scale from 0 (never or rarely) to 4 (almost always). The SAS has 6 subscales: FSB-Mental (8 items; e.g., Scanning the situation for an exit; α = .79), FSB-Avoidance (18 items; e.g., Avoiding social situations; α = .93), FSB-Reassurance Seeking/Over-preparation/Checking (27 items; e.g., Re-checking already-completed tasks; α = .93), FSB-Body Sensations: (13 items; e.g., Avoiding caffeine; α = .82), FSB-Companions (7 items; e.g., Relying on a companion for shopping; α = .79), and FSB-Substances (e.g., Carrying medications even if you don’t typically use them). The FSB-Substances scale typically has 9 items, including 2 concerning smoking. We removed the smoking items to prevent overlap with our dependent variable. The SAS also demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in prior work (Buckner, Zvolensky, Ecker, et al., 2017; Korte & Schmidt, 2014) and in the current sample (α = .97).

Smoking was assessed by asking “Do you smoke tobacco?” (yes or no). Those that endorsed smoking were asked, “How many cigarettes do you smoke per day on average?” To assess marijuana use frequency, participants were asked “On average, how often have you used marijuana in the past month?” with responses ranging from 0 (None) to 10 (21 or more times a week; Buckner, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2007). To assess drinking frequency, participants were asked “How often did you drink during the last month?” Participants responded using a scale from 0 (I did not drink at all) to 6 (Once a day or more; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985).

The Social Phobia Scale (SPS) and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) were used to assess trait social anxiety. The SPS and the SIAS each consist of 20 items that assess social anxiety from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The SPS and SIAS are companion measures and when used together, provide a relatively comprehensive assessment of social anxiety (e.g., fear of scrutiny in performance situations and anxiety related to social interaction in groups). To illustrate, the SPS has participants rate statements such as, “I become anxious if I have to write in front of other people,” whereas a statement on the SIAS is, “I have difficulty making eye-contact with others.” These measures have demonstrated good internal consistency in both community and undergraduate samples and have shown to be specific for social anxiety compared with other forms of anxiety (i.e., trait anxiety; Brown et al., 1997). The SIAS (α = .95) and the SPS (α = .95) demonstrated excellent internal consistencies in the current sample.

The depression subscale of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; D. Watson et al., 2007) assessed the degree to which one has experienced depression (e.g., “I felt inadequate”) in the past two weeks from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). This scale has good psychometric properties (D. Watson et al., 2007). The IDAS demonstrated excellent internal consistency in our sample (α = .91).

Four questions from the Infrequency Scale (Chapman & Chapman, 1983) were used to identify responders who provided random or grossly invalid responses. As in prior online studies (e.g., Cohen, Iglesias, & Minor, 2009), individuals who endorsed three or more items would be excluded.

Data analytic strategy

First, bivariate correlations were conducted to examine relations among study variables. Second, a hierarchical linear regression model tested the robustness of the relation between FSB and smoking. Predictor variables were: Step 1: gender, cannabis frequency, depression, and social anxiety given the relations of these variables to smoking and/or FSB (Buckner & Vinci, 2013; Buckner, Zvolensky, Businelle, et al., 2017); and Step 2: FSB (per Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

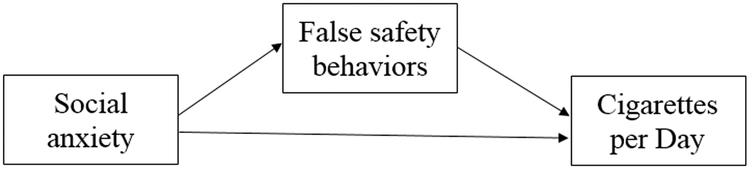

Third, we tested whether social anxiety was indirectly related to CPD via FSB (Figure 1) using PROCESS, a conditional process modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2018). All specific and conditional indirect effects were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses with 10,000 resamples from which a 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated. Although mediational models are ideally tested using prospective data, theoretically driven indirect effects models can be tested cross-sectionally to provide an initial test of the nature of the relations among variables (Hayes, 2013, 2018).

Figure 1.

Proposed mediation model of the indirect effect of social anxiety on cigarettes per day via frequency of false safety behavior use.

Analyses were conducted using a continuous measure of social anxiety given that social anxiety tends to be on a continuum and individuals scoring higher on this continuum report more smoking (e.g., Buckner & Vinci, 2013). To test whether results generalize to those with clinically elevated social anxiety, the indirect effects model was also conducted among individuals with clinically elevated or high social anxiety group (HSA; n = 24) who scored at or above the empirically supported clinical cutoff-scores of 34 for the SIAS and 24 for the SPS (Heimberg et al., 1992) compared to participants with normative or lower social anxiety (LSA; n = 23) who endorsed below the community sample means (Heimberg et al., 1992).

Results

Descriptive data and correlations

All but one participant (98.6%) reported using FSB to manage anxiety. The mean number of FSB used was 43.5 (SD = 18.2; range: 0–80). Bivariate correlations among study variables appear in Table 1. Of the FSB types, CPD was significantly correlated only with FSB-Avoidance. Social anxiety was significantly correlated with CPD and with FSB-Avoidance.

Table 1.

Descriptives and Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cigarettes per day | |||||||||||

| 2. Cannabis use frequency | .07 | ||||||||||

| 3. Drinking frequency | .11 | −.05 | |||||||||

| 4. Social anxiety | .25* | .04 | −.06 | ||||||||

| 5. Depression | .13 | .05 | .23 | .45** | |||||||

| 6. FSB-Mental | .10 | −.12 | .14 | .52** | .40** | ||||||

| 7. FSB-Avoid | .33** | −.10 | .20 | .65** | .57** | .68** | |||||

| 8. FSB-Reassurance | .19 | −.08 | .21 | .51** | .56** | .73** | .86** | ||||

| 9. FSB-Body sensations | .17 | .01 | .09 | .26* | .51** | .58** | .68** | .80** | |||

| 10. FSB-Companions | .06 | −.10 | .18 | .35** | .35** | .39** | .57** | .64** | .61** | ||

| 11. FSB-Substances | .10 | −.10 | .28* | .07 | .55** | .41** | .63** | .71** | .72** | .48** | |

| M (SD) | 3.28 (4.59) | 2.34 (3.38) | 2.92 (.93) | 43.10 (30.27) | 46.27 (13.66) | 1.67 (.79) | 1.09 (.81) | 1.12 (.70) | .76 (.60) | .97 (.80) | .86 (.77) |

Note: FSB = False safety behavior.

p < .05

p < .01

Robustness of the FSB-CPD relation

Results from the hierarchical linear regression testing the robustness of the relation between FSB-Avoidance and CPD appear in Table 2. Covariates were not significantly related to CPD. Avoidance-related FSB significantly accounted for an additional 5.9% of the variance in CPD.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Linear Regression Predicting Cigarettes Per Day (CPD).

| ∆R2 | ∆F | b | SD | B | t | p | sr2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Covariates | .08 | 1.08 | .61 | |||||

| Gender | .92 | 1.24 | 0.09 | 0.74 | .46 | .01 | ||

| Cannabis frequency | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.52 | .61 | .00 | ||

| Drinking frequency | −2.0 | .45 | −.06 | −.45 | .65 | .00 | ||

| Depression | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.47 | .87 | .03 | ||

| Social anxiety | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 1.50 | .14 | .00 | ||

| Step 2: FSB-Avoid | .06 | 4.36 | .01 | |||||

| FSB-Avoid | 2.02 | 0.97 | 0.36 | 2.09 | .04 | .06 |

Indirect effects

The full model with social anxiety and FSB-Avoidance1 significantly accounted for the variance in CPD, R2 = .11, F(2, 68) = 4.13, p = .020. Regarding direct effects, results of bootstrap analyses were consistent with those in Table 1 (social anxiety was related to FSB-Avoidance and CPD) and Table 2. FSB-Avoidance remained significantly related to CPD after accounting for variance attributable to social anxiety (Table 3). The indirect effect of social anxiety on CPD via avoidance-related FSB was estimated; greater social anxiety symptom severity was indirectly related to CPD via avoidance-related FSB, b = 0.03, SE = .02, 95% CI [.004, .090].

Table 3.

Bootstrap Analyses among Study Variables.

| b | SE | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = FSB-Avoidance | |||||

| Social anxiety | .02 | .00 | 7.09 | <.001 | [.01, .02] |

| DV = Cigarettes per Day | |||||

| Social anxiety | .01 | .02 | .23 | .819 | [−.04, .05] |

| FSB – avoidance | 2.02 | 0.97 | 2.09 | .041 | [.09, 3.95] |

Note: FSB = False safety behavior, DV = dependent variable.

With social anxiety group status (HSA vs LSA) as the independent variable, the full model also significantly accounted for the variance in CPD, R2 = .15, F(2, 46) = 4.12, p = .023. Social anxiety group was related to more FSB-Avoidance, b = 1.04, SE = .22, p < .001, 95% CI [.60, 1.48], but was no longer related to CPD after accounting for variance attributable to FSB-Avoidance, b = 1.01, SE = 1.64, p = .539, 95% CI [−2.29, 4.31]. The indirect effect model was significant, b = 1.82, SE = 1.40, 95% CI [.27, 5.36], suggesting that social anxiety group was related to CPD indirectly via FSB-Avoidance.

Discussion

This is the first known study to test whether smokers use FSB. Results indicated that nearly all smokers use FSB, but they use several different types of FSB, indicating that regardless of trait social anxiety levels, smokers overall engage in these maladaptive attempts to regulate anxiety. Further, FSB focused on avoidance was robustly related to CPD even after controlling for variance attributable to social anxiety, depression, gender, and cannabis use frequency (Abelson, 1985). Third, although social anxiety was related to CPD in the entire and clinical analogue samples, it was no longer related after accounting for FSB-Avoidance and social anxiety was indirectly related to CPD via avoidance-related FSB, suggesting that avoidance-related behaviors may play an especially important role in smoking among smokers with elevated social anxiety.

That avoidance-related FSB uniquely and robustly related to CPD is consistent with growing recognition that avoidance behaviors are robustly related to smoking outcomes (e.g., Farris, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2015). Avoidance-related FSB may contribute to smoking due to tendency to engage in maladaptive attempts to regulate anxiety and associated NA. Interestingly, results suggest that other types of FSB were not related to more CPD. Although future work is necessary to delineate reasons why avoidance-related FBS were related to CPD whereas others were not, it may be that some types of FBS (e.g., FSB-bodily sensations) were not related to CPD given the nature of smoking (e.g., physiological effects of smoking on bodily sensations).

Findings from our mediational analyses highlight the potentially causal role of avoidance-related FSB among smokers in smoking with elevated social anxiety (Hayes, 2018). Specifically, social anxiety was related to more FSB-avoidance which was related to more CPD. The specificity of FSB-avoidance as a putative mediator in the relation of social anxiety and smoking may be due in part to the nature of social anxiety itself. Social anxiety is characterized by avoidance of anxiety-provoking situations characterized by possible scrutiny or endurance of such situations with extreme distress. It may be that those individuals who endure anxiety-provoking situations utilize more adaptive strategies to manage their anxiety and associcated distress whereas those that engage in more avoidance also use other maladaptive strategies such as smoking. This is somewhat consistent with findings that more social avoidance (but not social anxiety) is related to increases in craving to smoke following exposure to emotional and substance-related cues (N. L. Watson et al., 2012) and that social avoidance (but not social anxiety) is robustly linked to other substance-related problems (Buckner, Heimberg, & Schmidt, 2011).

Findings have clinical implications. Given that nearly all smokers in our study used FSB, smokers may benefit from learning more adaptive ways to manage anxiety and associated NA. FSB use is malleable (Blakey & Abramowitz, 2016) and may therefore be a promising target in smoking cessation interventions, especially among those with elevated anxiety. Given that FSB-Avoidance was the only FSB related to CPD, it is noteworthy that cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) result in reduction of avoidance behaviors among individuals with social anxiety disorder (e.g., Aderka, McLean, Huppert, Davidson, & Foa, 2013; Hedman et al., 2013) and that reductions in avoidance are related to better smoking cessation outcomes (Farris et al., 2015). Thus, individuals with or without SAD may benefit from specifically targeting avoidance FSB via using CBT strategies during smoking cessation treatment.

The present study has several limitations that can inform future directions in this area. First, the study was cross-sectional, providing an important first test of these relations (Hayes, 2013); prospective research will be an important next step. Second, future work could benefit from multi-method approaches (e.g., biological verification of smoking). Third, participants were primarily White female undergraduates and replication with more diverse samples is necessary. Fourth, the sample was comprised of individuals who were not seeking smoking cessation treatment and future work is necessary to test whether results generalize to smoking cessation patients. Fifth, analyses concerned social anxiety because it is the most common anxiety condition among young adults (Kessler et al., 2005) and it is robustly and perhaps uniquely related to smoking (Sonntag et al., 2000). However, future work testing whether other types of anxiety are indirectly related to smoking via avoidance-related FSB is warranted. Further, an important next step will be to further delineate the ways in which avoidance as a FSB is related to smoking. For example, do these individuals choose to stay home and smoke rather than attend anxiety-provoking situations? Do they smoke during anxiety-providing situations in an attempt to manage physiological symptoms of arousal? Additionally, future work is necessary to test whether CBT results in decreases in FSB-related avoidance and whether such decreases are related to better smoking cessation outcomes.

Overall, findings provide initial empirical evidence that avoidance-related FSB are related to more CPD. Further, these behaviors may play an important role in the relation between social anxiety and smoking (Buckner, Farris, et al., 2014; Piper et al., 2011; N. L. Watson et al., 2012). Future work is needed to delineate the ways in which avoidance plays a role in smoking and to test the utility of the clinical implications listed above in informing efforts to prevent and treatment smoking among individuals generally and high-risk individuals such as those with social anxiety specifically.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided in part by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) located in Rockville, MD (R34DA031937). Funding was awarded to Dr. Julia Buckner. NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The full model with FSB-Avoidance, social anxiety, and covariates (gender, cannabis frequency, drinking frequency, depression) did not significantly predict CPD, R2 = .14, F (6, 64) = 1.67, p = .1422. Thus, the indirect effect model was run without the covariates.

References

- Abelson RP (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97(1), 129–133. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aderka IM, McLean CP, Huppert JD, Davidson JRT, & Foa EB (2013). Fear, avoidance and physiological symptoms during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(7), 352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista SR, Stewart SH, Fulton HG, Steeves D, Darredeau C, & Gavric D (2008). A further investigation of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to smoking motives. Addictive Behaviors, 33(11), 1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey SM, & Abramowitz JS (2016). The effects of safety behaviors during exposure therapy for anxiety: Critical analysis from an inhibitory learning perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, & Barlow DH (1997). Validation of the social interaction anxiety scale and the social phobia scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 9(1), 21–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.1.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2007). Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addictive Behaviors, 32(10), 2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, & Zvolensky MJ (2014). Direct and indirect relations of social anxiety on nicotine dependence and cessation problems: Multiple mediator analyses. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 16, 807–814. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Heimberg RG, & Schmidt NB (2011). Social anxiety and marijuana-related problems: The role of social avoidance. Addictive Behaviors, 36(1–2), 129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Lemke AW, & Walukevich KA (2017). Cannabis use and suicidal ideation: Test of the utility of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Psychiatry Research, 253, 256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, & Vinci C (2013). Smoking and social anxiety: The roles of gender and smoking motives. Addictive Behaviors, 38(8), 2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Businelle MS, & Gallagher MW (2017). Direct and indirect effects of false safety behaviors on cannabis use and related problems. The American Journal on Addictions. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Ecker AH, Jeffries ER, Lemke AW, Dean KE, … Gallagher MW (2017). Anxiety and cannabis-related problem severity among dually diagnosed outpatients: The impact of false safety behaviors. Addictive Behaviors, 70, 49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Jeffries ER, & Schmidt NB (2014). Robust impact of social anxiety in relation to coping motives and expectancies, barriers to quitting, and cessation-related problems. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 341–347. doi: 10.1037/a0037206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2002). Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2000. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5129a3.htm

- Chapman LJ, & Chapman JP (1983). Infrequency Scale. Unpublished test. Madison, WI:. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, & Wells A (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia In Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, & Schneider FR (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (Vol. 41, pp. 69–93). New York, NY US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Iglesias B, & Minor KS (2009). The neurocognitive underpinnings of diminished expressivity in schizotypy: what the voice reveals. Schizophrenia Research, 109(1–3), 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, & Cohen P (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Zvolensky MJ, Fitch KE, & Sachs-Ericsson N (2010). The role of comorbidity in explaining the associations between anxiety disorders and smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 12(4), 355–364. doi:doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2015). Smoking-specific experiential avoidance cognition: Explanatory relevance to pre- and post-cessation nicotine withdrawal, craving, and negative affect. Addictive Behaviors, 44, 58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Giovino GA, Hatziandreu EJ, Newcomb PA, … Davis RM (1990). Methods used to quit smoking in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263(20), 2760–2765. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440200064024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Kozak MJ (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20–35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, … Huang B (2005). The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(11), 1351–1361. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199507000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E, Mörtberg E, Hesser H, Clark DM, Lekander M, Andersson E, & Ljótsson B (2013). Mediators in psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: Individual cognitive therapy compared to cognitive behavioral group therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(10), 696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Mueller GP, Holt CS, Hope DA, & Liebowitz MR (1992). Assessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Behavior Therapy, 23(1), 53–73. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80308-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope K, Durrheim DN, d’Espaignet ET, & Dalton C (2006). Syndromic Surveillance: is it a useful tool for local outbreak detection? Journal Of Epidemiology And Community Health, 60(5), 374–375. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.035337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Marcy TW, & Naud S (2009). Interest in treatments to stop smoking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(1), 18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte K, & Schmidt NB (2014). Development and initial validation of the safety aid scale Paper presented at the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, & Bernstein A (2008). Anxiety sensitivity and smoking motives and outcome expectancies among adult daily smokers: Replication and extension. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 10(6), 985–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, & Clarke JC (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, & Crum RM (2013). Cigarette smoking and onset of mood and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), 1656–1665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.300911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2004). Health, United States, 2004 with Chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Government Printing Office. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccirillo ML, Dryman MT, & Heimberg RG (2016). Safety behaviors in adults with social anxiety: Review and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, Jorenby DE, & Baker TB (2011). Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: Relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction, 106(2), 418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03173.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM, Clark DM, & Hackmann A (1991). Treatment of panic attacks using cognitive therapy without exposure or breathing retraining. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29(2), 161–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(91)90044-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Pusser AT, Woolaway-Bickel K, & Preston JL (2012). Randomized controlled trial of False Safety Behavior Elimination Therapy (F-SET): A unified cognitive behavioral treatment for anxiety psychopathology. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 518–532. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag H, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Kessler RC, & Stein MB (2000). Are social fears and DSM-IV social anxiety disorder associated with smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents and young adults? European Psychiatry, 15(1), 67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00209-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health. (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (1988). The health consequences of smoking: Nicotine addiction - a report of the Surgeon General Rep. No. Publication No. (CDC 88–8406). Retrieved from Rockville, MD: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22014 [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, … Stuart S (2007). Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS). Psychological Assessment, 19(3), 253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NL, VanderVeen JW, Cohen LM, DeMarree KG, & Morrell HER (2012). Examining the interrelationships between social anxiety, smoking to cope, and cigarette craving. Addictive Behaviors, 37(8), 986–989. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bonn-Miller M, Bernstein A, & Marshall E (2006). Anxiety sensitivity and abstinence duration to smoking. Journal of Mental Health, 15(6), 659–670. doi: 10.1080/09638230600998888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]