Abstract

Pembrolizumab is a long-awaited drug for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. It is an immune checkpoint inhibitor, which has been shown to trigger new autoimmune disorders. We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced myasthenia gravis that occurred in an 84-year-old Japanese female with metastatic urothelial carcinoma in multiple organs. She developed right ptosis 3 days after the second pembrolizumab treatment. Although prednisolone was administered, her symptoms did not change and dysphagia appeared. She needed the steroid pulse therapy for treatment eventually. On the other hand, 9 weeks after the first pembrolizumab treatment, reductions in the sizes of liver and adrenal metastases was observed. However, unfortunately, the severe immune-related adverse events did not allow her to continue the administration of pembrolizumab for the treatment of multiple metastatic urothelial carcinoma. To our knowledge, this is the first case of myasthenia gravis associated with pembrolizumab treatment against metastatic urothelial carcinoma. In this case, a relationship between immune-related adverse events associated with myasthenia gravis and tumor responses to pembrolizumab was suspected, because marked reductions in the sizes of some metastatic lesions were observed after the administration of only two courses of pembrolizumab.

Keywords: Myasthenia gravis, Pembrolizumab, Immune-related adverse events, Anti-PD-1 antibody, Metastatic urothelial carcinoma

Background

Metastatic urothelial carcinoma (UC) is responsive to CDDP-based systemic chemotherapy with an initial response rate of 50–70%, however, eventually progresses with a median progression-free survival duration of only 7.4 months. For a long time no standard second line treatment for metastatic UC has been developed [1, 2]. In 2017, pembrolizumab, an anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (anti-PD-1) monoclonal antibody, was eventually approved for the treatment of metastatic UC. After approval, urologists experience immune-related adverse events (irAE) due to the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody.

Although the anti-PD-1 antibody also induces severe but rare immune-related side effects such as neurologic, endocrinologic or dermatologic disorders, the incidence of myasthenia gravis (MG) secondary to anti-PD-1 antibody therapy is extremely rare. MG is an autoimmune disease of the neuromuscular junction caused by antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) or muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), and leads to weakness and fatigue of skeletal muscle. Most MG patients require immune suppressive therapies such as corticosteroids, pyridostigmine bromide and intravenous immunoglobulin with long-term management. It has been reported that MG onset occurred in the early phase after anti-PD-1 treatment with rapid progression [3]. Here, we describe the first case of new onset myasthenia gravis in a patient treated with pembrolizumab for metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Case presentation

An 84-year-old Japanese female with metastatic UC developed right ptosis 3 days after the second administration of 200 mg pembrolizumab. She also had progressive fatigable weakness and was unable to walk by herself. She had no previous history of neuromuscular disorders.

Fourteen months before onset of her right ptosis, she was diagnosed with muscle invasive bladder cancer and underwent total cystectomy and bilateral ureterocutaneostomy after the administration of two courses of neoadjuvant GC chemotherapy. Twelve months after surgery, a follow-up CT scan showed multiple mediastinal lymph node swellings, multiple liver and lung metastases, and bilateral adrenal masses (Fig. 1a). Biopsy of the liver mass confirmed the histological type of UC. GC chemotherapy was initiated, but subsequently stopped after one course due to disease progression. The administration of 200 mg pembrolizumab was started 25 days before the onset of ptosis. Neurological examination revealed right ptosis, dropped head, and weakness of the lower extremities. Edrophonium test and ice pack test did not confirm the improvement of ptosis. Laboratory findings showed an elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) level of 828 IU/L, however, anti-AChR and, anti-MuSK antibodies were negative. Although repetitive stimulation showed no decrement, needle electromyography revealed myopathic changes. Muscle MR-image of the neck showed an atrophic paraspinal muscle, but not high intensity signals. In addition, we performed single fiber electromyography and detected the expansion of jitter. Finally, further serological investigation detected the positivity of anti-titin antibody, one of anti-striational antibodies, in her serum.

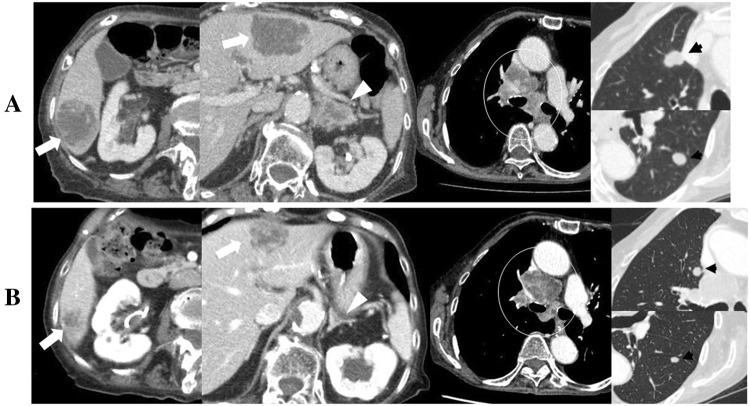

Fig. 1.

CT scan findings a before and b 9 weeks after the first administration of 200 mg pembrolizumab showing multiple liver (white arrow) and adrenal metastases (white arrow head), mediastinal lymph node swelling (white circle), and lung metastases (black arrows)

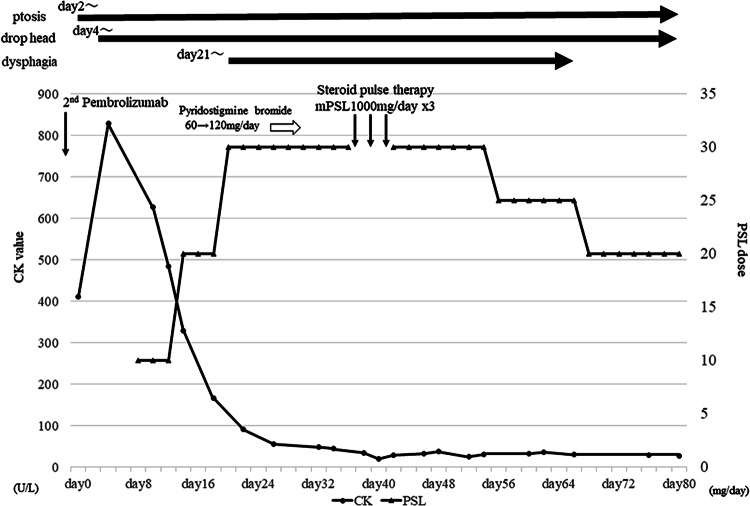

Based on clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed as MG with myositis associated with pembrolizumab. Figure 2 shows the clinical course of her symptoms, the detail of MG treatment and laboratory data of the CK value. Prednisolone was administered at 10 mg/day, and the dose was then increased to 30 mg/day. Although CK levels immediately normalized after the treatment, her symptoms did not change and dysphagia appeared. The administration of pyridostigmine bromide was initiated, but subsequently discontinued because of severe digestive symptoms. Dysphagia progressed and the insertion of a gastric tube was necessary (MG foundation of America class: IVb). The patient started 3 days of steroid pulse therapy (1000 mg/day) followed by oral prednisolone at a dose of 30 mg. After steroid pulse therapy, dysphagia and dropped head slowly improved. She was discharged 45 days after steroid pulse therapy with 20 mg/day of prednisolone. Due to the severity of the irAE, we could neither re-start the administration of pembrolizumab nor treat with a third line regimen such as taxane-based chemotherapy.

Fig. 2.

Schema showing the clinical course of the patient’s symptoms, the detail of MG treatment and laboratory data of the CK value. CK creatine kinase, PSL prednisolone, mPSL methylprednisolone

The patient only received two courses of pembrolizumab and a CT scan 5 weeks after the first pembrolizumab treatment showed slight reductions in the sizes of all metastatic lesions. A CT scan 9 weeks after the first pembrolizumab treatment revealed further reductions in the sizes of liver and adrenal metastases, no changes in lung metastases, and increases in mediastinal lymph node swellings (Fig. 1b). A CT scan 13 weeks after the first pembrolizumab treatment showed that the sizes of some liver and lung metastases began to increase and those of mediastinal lymph node swellings continued to increase, whereas those of bilateral adrenal metastases continued to decrease.

Conclusions and discussion

Pembrolizumab is a long-awaited drug for the treatment of metastatic UC. It is an immune checkpoint inhibitor, which has been shown to trigger new autoimmune disorders. The 2019 EAU guideline and 2019 NCCN guideline state that pembrolizumab is a preferred regimen for patients exhibiting disease progression during or after platinum-based combination chemotherapy for metastatic UC. On the other hand, the occurrence of irAE due to the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody needs to be carefully considered.

Suzuki et al. previously reported that MG cases accounted for 0.12% of 9869 Japanese cancer patients treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab [3]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related MG in a patient with metastatic UC. To date, 13 cases of pembrolizumab-related MG have been reported in other types of cancers, 3 of which died due to pembrolizumab-related MG [4–6]. Only two cases were treatable with oral corticosteroids alone. In most cases, not only oral corticosteroids, but also steroid pulse therapy and/or intravenous immunoglobulin and even plasma exchange were necessary for the treatment of MG. These findings revealed that anti-PD-1 antibody-related MG was not a frequent side effect, but may be severe if occurred. In the present case, we initially hesitated to use high-dose steroids due to the advanced age of the patient. However, her symptoms progressed and she eventually needed steroid pulse therapy.

The relationship between the occurrence of irAE and anti-cancer efficacy has recently been reported in various types of cancer patients treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody. Previous studies reported that among patients with non-small lung cancer [7, 8] or melanoma [9], those who developed irAE after anti-PD-1 antibody therapy showed more favorable therapeutic efficacy than those who did not develop the irAE. Of the ten case reports on pembrolizumab-related MG described above, an imaging study to evaluate therapeutic efficacy was performed on six cases, showing partial responses in two, stable disease in two, and disease progression in two [10–14]. In the present case, the possibly of a relationship between irAE associated with MG and tumor responses to pembrolizumab was suspected, because marked reductions in the sizes of some liver metastases and bilateral adrenal metastases were observed after the administration of only two courses of pembrolizumab. Unfortunately, the severe irAE associated with MG did not allow us to continue the administration of pembrolizumab for the treatment of multiple UC metastases.

Funding

There was no funding for this paper.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Eiji Kikuchi received honoraria from ONO, KISSEI, ASKA, NIPPON SHINYAKU, TAIHO, TAKEDA, MSD, PHISER, Astra Zeneca, Astellas, Chugai, and research funding from MSD, NIPPON KAYAKU, Astellas, ONO, Chugai, TAKEDA, TAIHO, Astra Zeneca. Mototsugu Oya received honoraria from MSD. Nozomi Hayakawa and Shigeaki Suzuki have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

We obtained written informed consent from patient’s next of kin (her son), because she had already dead.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kubota Y, Nakaigawa N, The Committee for Establishment of the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Bladder Cancer and the Japanese Urological Association Essential content of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for bladder cancer: the Japanese Urological Association 2015 update. Int J Urol. 2016;23:640–645. doi: 10.1111/iju.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer : results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068–3077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki S, Ishikawa N, Konoeda F, et al. Nivolumab-related myasthenia gravis with myositis and myocarditis in Japan. Neurology. 2017;89:1127–1134. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alnahhas I, Wong J. A case of new-onset antibody-positive myasthenia gravis in a patient treated with pembrolizumab for melanoma. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55:E25–E26. doi: 10.1002/mus.25496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.March KL, Samarin MJ, Sodhi A, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced myasthenia gravis: a fatal case report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24:146–149. doi: 10.1177/1078155216687389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earl DE, Loochtan AI, Bedlack RS. Refractory myasthenia gravis exacerbation triggered by pembrolizumab. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57:E120–121. doi: 10.1002/mus.26021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato K, Akamatsu H, Murakami E, et al. Correlation between immune-related adverse events and efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2018;115:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, et al. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:583–589. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, et al. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:886–894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen BH, Kuo J, Budiman A, et al. Two cases of clinical myasthenia gravis associated with pembrolizumab use in responding melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:152–154. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau KH, Kumar A, Yang IH, et al. Exacerbation of myasthenia gravis in a patient with melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54:157–161. doi: 10.1002/mus.25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh SY, Shin SH, Kim MK, et al. Emergence of myasthenia gravis with myositis in a patient treated with pembrolizumab for thymic cancer. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14:115–117. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez NL, Puwanant A, Lu A, et al. Myasthenia triggered by immune checkpoint inhibitors: new case and literature review. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27:266–268. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmer L, Goldinger SM, Hofmann L, et al. Neurological, respiratory, musculoskeletal, cardiac and ocular side effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:210–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]