Abstract

Standard therapy for metastatic small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP) remains undefined. We have effectively treated relapsed SCCP with amrubicin. A 72-year-old patient, diagnosed with T4N1M0 prostate cancer, started hormonal therapy in May 2012, elsewhere, and his prostate-specific antigen levels remained low. However, pulmonary and hepatic metastases occurred; high neuron-specific enolase levels suggested SCCP, which was confirmed by repeated biopsy at our institution. In October 2016, chemotherapy with irinotecan and cisplatin was initiated for metastases to the lung, liver, and left pelvic lymph nodes, and partial response (PR) was achieved. After six cycles, brain metastases occurred. After ten cycles, his pro-gastrin-releasing peptide levels increased suddenly, and brain and hepatic metastases enlarged. Amrubicin was started in December 2016 and seven cycles were safely completed, with PR and markedly reduced brain metastasis volume, until his pneumonitis-related death in June 2017. Amrubicin may be an effective second-line chemotherapy option for SCCP.

Keywords: Amrubicin, Prostate, Relapse, Small cell carcinoma, Brain metastases

Introduction

Small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP) is a rare entity, first reported by Wenk et al. in 1977 [1, 2], and is an extremely aggressive type of prostate carcinoma [3]. The cumulative number of patients with SCCP is small and the standard therapy for metastatic SCCP has not yet been established. Hence, patients with SCCP have been treated with regimens patterned after those for small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC). Herein, we report a case of SCCP treated with amrubicin as a second-line chemotherapy, resulting in the shrinkage of the patient’s brain metastases.

Case report

A 68-year-old man visited a clinic because of urinary retention in March 2012. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was as high as 23.34 ng/mL. Prostate cancer, at stage B2 cT2cN0M0 (Gleason score, 5 + 4 = 9), was diagnosed and radical prostatectomy was attempted, but was impossible due to deep rectal invasion. The patient had metastases to the bilateral obturator lymph nodes. The postoperative staging was cT4N1M0. He started complete androgen blockade and his PSA levels remained at 1–2 ng/mL. However, pulmonary and hepatic metastases occurred, and a high level of neuron-specific enolase (NSE: normal limit, < 16.3 ng/mL) was identified.

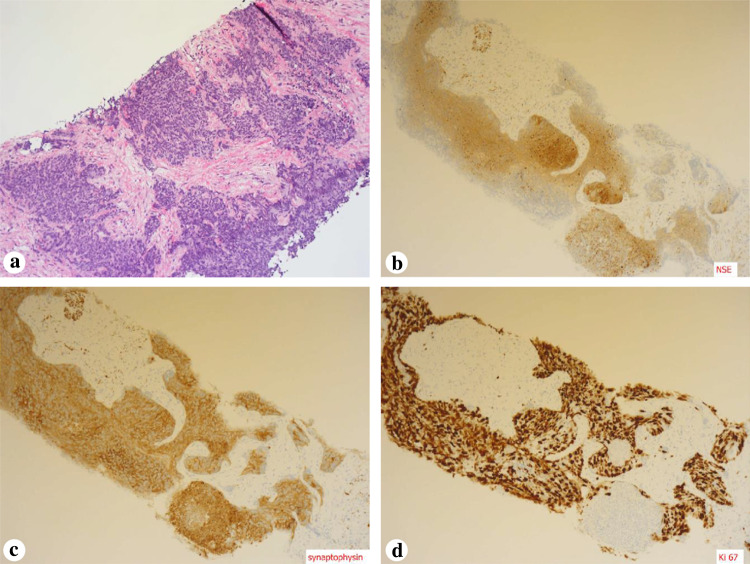

In October 2015, he was referred to our department because of suspected SCCP. On presentation, his NSE and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP: normal limit, < 81.0 pg/mL) levels were high (76.6 ng/mL and 2832.9 pg/mL, respectively), while his PSA level was low (1.19 ng/mL). Metastases to the lung, liver, and pelvic lymph nodes and enlargement of the local prostatic lesion were detected. Repeated biopsy of the prostate was performed, and small cell carcinoma was found in all ten biopsy specimens, mixed with adenocarcinoma in six specimens. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining for NSE and synaptophysin; the percentage of Ki-67 antigen-positive cells was 90% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical findings a Small cell carcinoma is revealed by hematoxylin–eosin stain of a prostate biopsy sample. b Immunohistochemistry demonstrates positive staining for neuron-specific enolase (NSE). c Immunohistochemistry demonstrates positive staining for synaptophysin. d Immunohistochemistry demonstrates positive staining for Ki 67

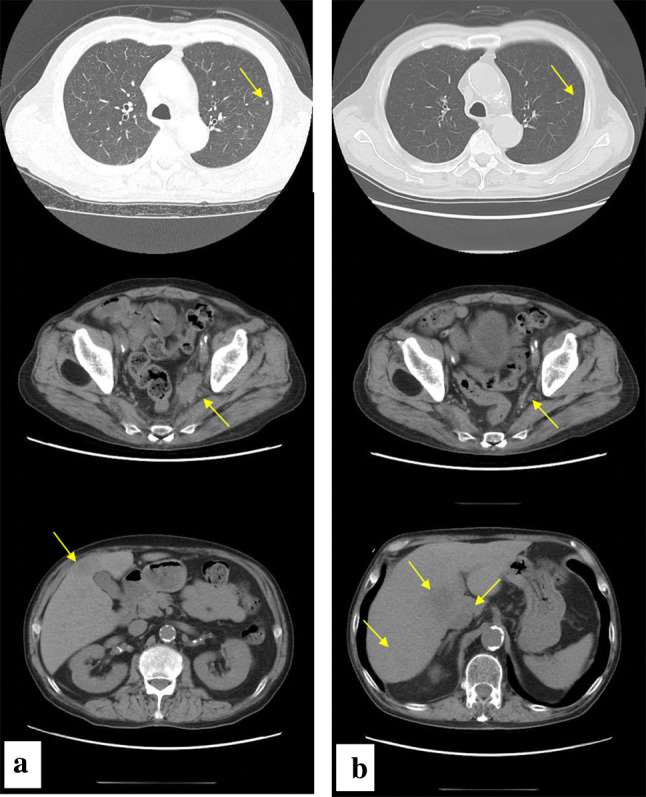

From October 2015, chemotherapy with irinotecan (CPT-11) at 60 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 and cisplatin (CDDP) at 60 mg/m2 on day 1 was introduced. After two cycles, the pulmonary and hepatic metastases disappeared and metastases to the pelvic lymph nodes were reduced in size; thus, partial response (PR) was achieved. However, ProGRP levels increased and multiple brain metastases were found after six cycles. After completion of ten cycles (Fig. 2), a sharp elevation of ProGRP and NSE levels and enlargement of the multiple brain metastases and hepatic metastasis were detected.

Fig. 2.

Neck ~ pelvic computed tomography before (a) and after (b) chemotherapy with irinotecan and cisplatin; Pulmonary metastases (arrows) disappeared. Metastases to pelvic lymph nodes (arrows) were reduced in size. Hepatic metastases (arrows) increased in number and size

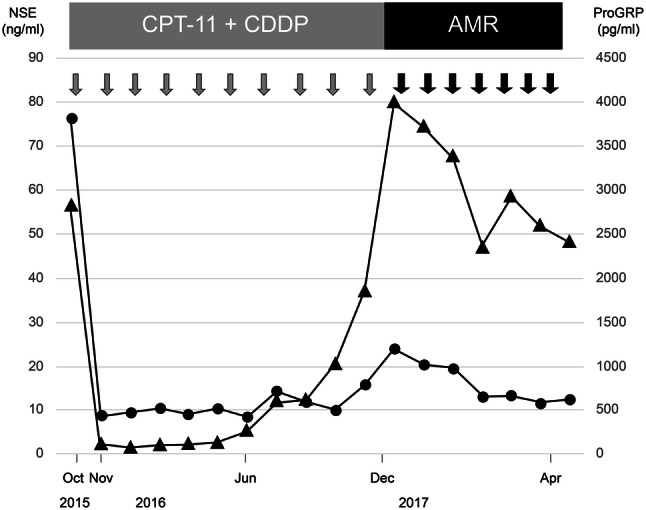

As second-line chemotherapy, amrubicin (AMR) was administered at 40 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, and 3. From December 2016, seven cycles in total were administered, and the multiple brain metastases shrank markedly; thus, a PR was achieved (Fig. 3). An adverse reaction (grade 4 neutropenia, according to the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria [version 4]) occurred on days 12 and 13, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was administered; febrile neutropenia did not develop. The other adverse reactions included grade 2 thrombocytopenia (on day 13) and grade 1 diarrhea (on days 9–14). He died in June 2017, due to pneumonitis, 6 months after initiation of AMR. His clinical course is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Gadolinium-enhanced brain magnetic resonance images before (a) and after (b) chemotherapy with amrubicin; Multiple brain metastases (arrows) were markedly shrunk

Fig. 4.

Clinical course of chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP), including trends in tumor marker plasma levels, i.e., neuron-specific enolase (NSE; circles) and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP; triangles)

Discussion

SCCP is a rare entity and accounts for 0.5–2% of primary prostate tumors [2]. It is reportedly identified in 20% of autopsy cases of castration-resistant prostate cancer [4]. Prostate biopsy is essential for a definite diagnosis of SCCP, which is confirmed by the histology; positive staining for markers such as NSE and synaptophysin on immunohistology assists in confirming the diagnosis of SCCP. Serum markers, such as NSE and ProGRP, are also useful for confirming the diagnosis and their levels reflect the tumor burden and disease progression [5]. SCCP is histologically classified into three types: (a) pure SCC, (b) a mixed type comprising adenocarcinoma and SCC, and (c) development of SCCP during treatment of adenocarcinoma [6]. The present case was classified as type (c). The prognosis of SCCP is poor, with a median survival time of 5–17.5 months [2]. Chemotherapy is indicated for metastatic SCCP, but no standard treatment regimen has been established to date [7]. Chemotherapy for SCCP should be modeled after that used for SCLC (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] guidelines for treatment of prostate cancer, version 3, 2016). In the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of SCLC (version 2, 2017), AMR is described as one of the effective agents in patients with relapsed or refractory SCLC. AMR is a relatively new anthracycline agent used for treatment of lung cancer, and became commercially available in Japan in 2002. AMR is reported to be highly effective in patients with relapsed SCLC in particular [8]. The total dose of AMR is not limited, since AMR, unlike other anthracycline agents has no cumulative dose-dependent cardiotoxicity [9]. Long-term administration of AMR is possible with appropriate management of adverse reactions to the drug, including myelosuppression and diarrhea.

At present, the treatment options for relapsed SCCP following cisplatin (carboplatin) plus etoposide or irinotecan are chemotherapy with AMR and radiation therapy. Yumiba summarized of 2nd line chemotherapy regimen with SCCP: two cases of irinotecan plus cisplatin (mean response period: 0 months), one case of etoposide plus carboplatin (mean response period: 5 months), three cases of amrubicin (mean response period: 2 months), and two cases of docetaxel (data not shown) [10]. AMR was the only regimen reported as the 2nd regimen alone. Table 1 shows a summary of reports of AMR treatment of SCCP [5, 11–13]. AMR was administrated as 2nd line regimen, except No.3 case. The best overall rating were SD or more. On the other hand, radiation therapy was reported in a case report that prostate tumors shrank remarkably [2]. Radiation therapy may be considered if the prostate tumors grow and local control of urination is required even in metastatic cases.

Table 1.

Case with SCCP treated with AMR

| No. | Author | Year | Age | Findings before therapy with AMR | Chemotherapy line | Administration cycle of AMR | Best overall rating (RECIST) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSA (ng/ml) | NSE (ng/ml) | Pro GRP (pg/ml) | |||||||

| 1 | Kageyama | 2006 | 65 | – | 50 | 110 | 3 | 1 | Stable disease |

| 2 | Kageyama | 2006 | 73 | 0.6 | 52 | 23 | 2 | 2 | Stable disease |

| 3 | Katou | 2008 | 23 | 1.38 | 37 | – | 1 | 1 | Partial response |

| 4 | Asai | 2014 | 76 | 0.01 | – | – | 2 | 8 | Partial response |

| 5 | Hirai | 2015 | 69 | 0.22 | 16.3 | 578 | 2 | 12 | Stable disease |

| 6 | Case | 2018 | 72 | 2.17 | 24.2 | 3996.2 | 2 | 7 | Partial response |

In previous reports on the use of AMR in the first three cases of SCCP, the administration period was as short as 1–2 cycles, due to poor performance status [5] and diarrhea [11]. On the other hand, our patient received a relatively long-term administration of AMR (seven cycles) without experiencing serious adverse events. Additionally, the brain metastases shrank during the administration of AMR. This may be explained by the ability of AMR to cross the blood–brain barrier and to be distributed in the cerebrum and cerebellum at almost the same concentration as that in the blood. In Japan, medical insurance does not cover AMR for the treatment of prostate cancer. Thus, we obtained the approval for the use of AMR in patients with SCCP from the Chemotherapy Committee of our hospital and obtained informed consent from the patients before implementing AMR treatment.

AMR may be an effective treatment option as a second-line chemotherapy for SCCP. It is important to evaluate the efficacy and safety of AMR in patients with SCCP in a large case series.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wenk RE, Bhagavan BS, Levy R, et al. Ectopic ACTH, prostatic oat cell carcinoma, and marked hypernatremia. Cancer. 1977;40:773–778. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197708)40:2<773::AID-CNCR2820400226>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anker CJ, Dechet C, Isaac JC, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1168–1171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmgren JS, Karavadia SS, Wakefield MR. Unusual and underappreciated: small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:22–29. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka M, Suzuki Y, Takaoka K, et al. Progression of prostate cancer to neuroendocrine cell tumor. Int J Urol. 2001;8:431–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kageyama S, Narita M, Kim CJ, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three patients and a prognostic analysis of cases reported in Japan. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2006;52:809–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yashi M, Terauchi F, Nukui A, et al. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma as a variant form of prostate cancer recurrence: a case report and short literature review. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadal R, Schweizer M, Kryvenko ON, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;1:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YH, Mishima M. Second-line chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higashiguchi M, Suzuki H, Hirashima T, et al. Long-term amrubicin chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1423–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yumiba S, Asakura T, Okada T, et al. Etoposide and carboplatin effective for treatment of small cell carcinoma of prostate : a report of two cases. Hinyoukika Kiyo. 2016;62(12):639–645. doi: 10.14989/ActaUrolJap_62_12_639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katou M, Soga N, Onishi T, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate treated with amrubicin. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:169–172. doi: 10.1007/s10147-007-0702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asai S, Sakatani T, Mizuno K, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate effectively treated by chemotherapy: a report of two cases. Nishinihon J Urol. 2014;76:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirai M, Konishi T, Saito K, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate: a case report of relative long-term survival. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;106:280–284. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol.106.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]