Abstract

Thalidomide, originally developed as a sedative drug, causes multiple defects due to severe teratogenicity, but it has been re-purposed for treating multiple myeloma, and derivatives such as lenalidomide and pomalidomide have been developed for treating blood cancers. Although the molecular mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives remained poorly understood until recently, we identified cereblon (CRBN), a primary direct target of thalidomide, using ferrite glycidyl methacrylate (FG) beads. CRBN is a ligand-dependent substrate receptor of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex cullin-RING ligase 4 (CRL4CRBN). When a ligand such as thalidomide binds to CRBN, it recognizes various ‘neosubstrates’ depending on the shape of the ligand. CRL4CRBN binds many neosubstrates in the presence of various ligands. CRBN has been utilized in a novel protein knockdown technology named proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs). Heterobifunctional molecules such as dBET1 are being developed to specifically degrade proteins of interest. Herein, we review recent advances in CRBN research.

Keywords: thalidomide, lenalidomide, immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs), cereblon, ubiquitin, proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs)

Introduction

In 1954, thalidomide (Fig. 1A) was developed as a sedative hypnotic drug by the German pharmaceutical company Grunenthal. No remarkable toxicity was detected when tested on rodents, and thalidomide was sold to more than 40 countries. However, in the early 1960s, McBride and Lenz independently reported that thalidomide is highly teratogenic. When pregnant women take thalidomide, newborn infants suffer severe developmental defects such as phocomelia and small ear. Although this drug was withdrawn from the market, researchers continued studying its mechanism of action and activity.1–3)

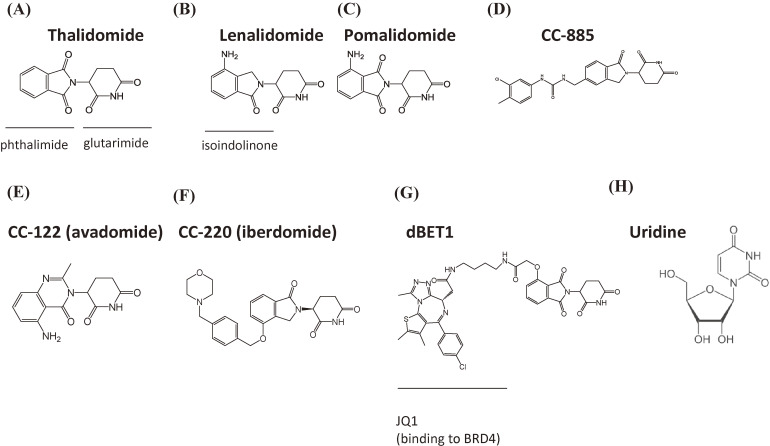

Figure 1.

Structure of CRBN-binding drugs. (A) Thalidomide. (B) Lenalidomide. (C) Pomalidomide. (D) CC-885. (E) CC-122. (F) CC-220. (G) dBET1, composed of JQ1 (a BRD4 inhibitor) and thalidomide. (H) Uridine.

In 1965, an Israeli physician found that thalidomide is effective for treating erythema nodosum leprosum, a specific type of leprosy resulting in painful skin lesions.4) During the 1980s and early 1990s, thalidomide was found to be an effective treatment for certain autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and chronic graft versus host disease,5–7) and thalidomide decreases tumor necrosis factor-α production.8,9) In 1994, thalidomide was shown to inhibit angiogenesis,10) and in 1999, thalidomide was demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of multiple myeloma.11) The use of thalidomide for treating erythema nodosum leprosum and multiple myeloma was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the U.S. in 1998 and 2006, respectively. In Japan, the use of thalidomide for the treatment of multiple myeloma was approved in 2008. Because thalidomide is associated with serious teratogenicity, its use is strictly controlled by the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS) program in the U.S. and the Thalidomide Education and Risk Management System (TERMS) in Japan.12,13) Thalidomide represents one of the most successful cases of drug repositioning.

Recently, several thalidomide derivatives have been developed as immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs).14,15) Among these, lenalidomide and pomalidomide have potent anti-cancer activity (Fig. 1B and 1C), both drugs exert clinically beneficial effects against multiple myeloma, and they have already been approved by the U.S. and Japan. Lenalidomide also possesses therapeutic activity for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome (5q-), mantle cell lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.16–22)

The effects of thalidomide are pleiotropic, hence there are believed to be numerous molecular targets of this drug. The direct target of thalidomide was not known until recently due to technical limitations. However, our group developed new affinity matrices (styrene glycidyl methacrylate [SG] and ferrite glycidyl methacrylate [FG] beads) for isolating drug-binding proteins.23,24) Using FG beads, in 2010 we identified cereblon (CRBN) as the sole direct target responsible for thalidomide teratogenicity.25) Various researchers have subsequently investigated the role of CRBN in the effects of thalidomide. CRBN is now considered a primary direct target for both the anti-cancer activity and teratogenicity of thalidomide.26,27)

CRBN forms a cullin-really interesting new gene (RING) ligase-4 (CRL4) ubiquitin ligase (E3) complex with damage-specific DNA-binding protein 1 (DDB1), Cullin 4 (Cul4), and Regulator of cullins-1 (Roc1).25,28,29) When thalidomide or its derivatives bind to CRBN, CRBN can recognize drug-dependent ‘neosubstrates’ for subsequent ubiquitination and protein degradation. Substrate selectivity is dependent on the structure of CRBN-binding compounds,26,30) and novel medicines that target CRBN are being eagerly sought. In particular, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) have been developed using CRBN, and this technology is attracting the attention of researchers and the pharmaceutical industry.31,32)

In this review, we summarize the molecular mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives. In addition, we introduce various applications of thalidomide-like compounds, with particular emphasis on CRBN approaches.

Development of drug target deconvolution

Identifying the direct target proteins of small chemical ligands such as pharmaceutical drugs is called target deconvolution. There are several methods for achieving target deconvolution, including affinity purification using ligand-immobilized affinity matrices, photoaffinity labeling, cellular thermal shift assay, activity-based protein profiling, and drug affinity responsive target stability analysis.33) Among these, we employed affinity purification and have been developing new affinity matrices for more than 30 years. Agarose is conventionally used as an affinity matrix, and in 1986 Tjian and colleagues identified transcription factor Sp1, which binds to a specific DNA sequence, using DNA-immobilized agarose beads.34) This ground-breaking discovery demonstrated the power of the purification technique for isolating ligand-specific binding proteins. However, numerous non-specific proteins tend to interact with hydrophobic compounds present in this matrix, including the hydrophobic thalidomide, and this is partially why target deconvolution failed for a long time for this molecule. Therefore, we developed non-porous, physically stable matrices that were small and highly dispersive, with surfaces that tend not to bind proteins non-specifically, and it is easy to modify the reactive groups for drug fixation because these stable matrices are tolerant to organic solvents. The smaller size of these beads results in a larger surface area, which is advantageous.

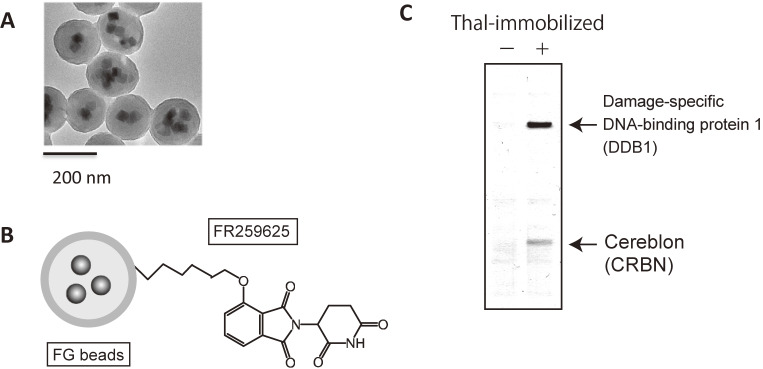

We first developed SG beads, the core of which is composed of copolymers of styrene and glycidyl methacrylate forms an outer coating. These beads have a diameter of ∼200 nm, can form a single-bead dispersion in water, and can be collected by centrifugation.23) We next developed FG beads (Fig. 2A),24) which were similar to SG beads, but the core was composed of ferrite (Fe3O4) nanocrystals surrounded by copolymers of styrene and glycidyl methacrylate. Magnetic separation is possible using FG beads, which avoids centrifugation, and non-specific background is also reduced using affinity purification. SG and FG beads are currently produced by Tamagawa Seiki Co., Ltd, and they are commercially available. We used these beads for isolating various target proteins of pharmaceutical drugs and other bioactive metabolites.35–45)

Figure 2.

Affinity purification technique using FG beads. (A) Electron microscopy image of FG beads. (B) Schematic representation of FG beads. (C) Affinity purification of cereblon and DDB1 from human cell extracts using FG beads.

Identification of a primary direct target of thalidomide using FG beads

Thalidomide is composed of two parts: a phthalimide ring and a glutarimide ring. We synthesized thalidomide derivative FR259625, which has a carboxylic acid group, and covalently attached it through this group to amino groups on FG beads (Fig. 2B). Using the resulting thalidomide-immobilized FG beads, we attempted to isolate target proteins from various cell extracts (Fig. 2C), and managed to purify two proteins with molecular weights of ∼55 kDa and ∼127 kDa. The smaller and larger proteins were identified as CRBN and DDB1, respectively. Using recombinant proteins purified from insect cells, we found that CRBN binds directly to thalidomide, while DDB1 binds directly to CRBN and interacts indirectly with thalidomide.

CRBN is a 441 or 442 amino acid protein that is evolutionally conserved from plants to humans and is associated with intellectual disability.46) Although the biochemical functions of CRBN are largely unknown, identification of DDB1 provided an important clue, because DDB1 was originally identified as a DNA repair factor that forms a heterodimer with DDB2.47,48) However, as mentioned above, this protein is now known to be an adaptor protein of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4.28) From yeasts to humans, intracellular protein levels are precisely regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, in which the E3 enzyme catalyzes the transfer of polyubiquitin chains from the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (E2) component to target proteins, thereby targeting them for degradation by the proteasome.49) CRL forms the largest E3 family, with over 700 types.50) The classification of CRLs is based on the type of Cullin protein, of which at least seven types (Cul1, Cul2, Cul3, Cul4A, Cul4B, Cul5, and Cul7) are known. Cullin proteins bind to Roc1 to form the catalytic core of CRL. CRL4 consists of four proteins (Roc1, Cul4 4A or 4B, DDB1), and a substrate receptor. DDB1 is an adaptor protein that connects the substrate receptor to the N-terminus of Cul4 (Cul4A or Cul4B) to form a substrate recruitment core that recognizes specific target proteins for ubiquitination and degradation. There are many known substrate receptors, known as DDB1- and Cul4-associating factors, including DDB2 and CDT2.29,48,51) DDB2 recognizes the DNA repair factor Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C, while CDT2 recognizes the Chromatin licensing and DNA replication factor 1.52,53) We found that CRBN competes with DDB2 for binding to DDB1, and CRBN is auto-ubiquitinated along with DDB2.54) Notably, the auto-ubiquitination of CRBN is inhibited by thalidomide. Therefore, we concluded that CRBN is a novel substrate receptor of CRL4 and a biochemical target of thalidomide.

CRBN is crucial for thalidomide teratogenicity

Rodents are resistant to thalidomide; therefore, we used zebrafish as a model animal to investigate whether CRBN is involved in thalidomide teratogenicity. Zebrafish have transparent bodies, their embryos grow rapidly, and they are used widely in pharmaco-toxicological studies.55) It is possible to observe the pectoral fin within 3 days after fertilization, and ectopic expression can also be studied by mRNA injection. Thalidomide induces serious developmental defects in the fins and ears of other thalidomide-sensitive animals, and the zebrafish CRBN homolog zCRBN binds to both DDB1 and thalidomide.25) To investigate whether CRBN is a genuine target for thalidomide teratogenicity, we constructed a thalidomide binding-deficient CRBN mutant, in which both Y384 and W386 were replaced with alanine, which can form the CRL4 complex. We then demonstrated that zebrafish embryos expressing this mutant are resistant to thalidomide treatment.

In limb and fin development, fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) has been shown to be essential,56,57) and a previous report found that thalidomide downregulates the expression of FGF8 in rabbits.58) We confirmed that FGF8 expression is downregulated by thalidomide treatment in zebrafish, and downregulation is reversed by ectopic expression of a thalidomide binding-deficient Y384A and W386A CRBN mutant. Finally, we used chicks and confirmed that the teratogenic pathway is evolutionary conserved in different species. Treatment with thalidomide retarded the growth of limbs in chicks, and drug binding-deficient mutants abolished the limb defects. Therefore, we concluded that CRBN is a primary target for thalidomide teratogenicity.25)

Identification of CRBN was an important discovery in the field of thalidomide research. Many researchers subsequently began analyzing the function of CRBN, but several important questions remain: (1) Is CRBN involved in the therapeutic effects of thalidomide? (2) What are the substrates of CRBN? (3) What is the protein structure of CRBN, and how is this related to function? (4) Why are rodents resistant to thalidomide?

CRBN is required for the therapeutic effects of thalidomide and its derivatives

Researchers, including our group, first investigated whether CRBN is associated with the therapeutic effects of thalidomide. Pomalidomide is a thalidomide derivative with an amino substituent at the four position of the phthalimide ring (Fig. 1C). Lenalidomide is similar to pomalidomide but lacks a carbonyl group (Fig. 1B), and this compound was found to decrease IRF4 expression and cause growth defects in myeloma cells before CRBN was identified.59) The relationship between the anti-myeloma effects and CRBN is intriguing. Stewart and colleagues showed that RNA interference-mediated knockdown of CRBN confers IMiD resistance to myeloma cells.60) Furthermore, a pomalidomide-resistant myeloma cell type was shown to lack CRBN expression.60) Our group and others have shown that CRBN binds not only to thalidomide but also to lenalidomide and pomalidomide, and CRBN binds more strongly to these two derivatives than thalidomide. It was confirmed that IMiD treatment downregulated the expression of IRF4, an essential survival factor, resulting in antiproliferative effects in myeloma.61) Therefore, it was concluded that CRBN is required for the anti-myeloma effects of thalidomide and IMiDs.

Identifying CRBN substrates was the next priority, and two research groups independently showed that lenalidomide induces the degradation of transcription factors Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 (Ikaros) and Ikaros family zinc finger protein 3 (Aiolos) mediated by CRL4CRBN.62,63) Ebert and colleagues rediscovered CRBN as a primary direct target of lenalidomide using drug-immobilized affinity chromatography,62) and both groups found that lenalidomide confers CRBN with the ability to recognize Ikaros and Aiolos as neosubstrates. Ikaros and Aiolos belong to the Ikaros family of proteins involved in lymphocyte differentiation. Other Ikaros family proteins, such as Helios and Eos, are not degraded by lenalidomide, and Ikaros and Aiolos are important for IRF4 expression. Expression of CRBN-binding deficient mutants of Ikaros or Aiolos suppressed the antiproliferative effect of lenalidomide in myeloma cells. Therefore, it was concluded that breakdown of Ikaros and Aiolos drives the anti-myeloma effects of lenalidomide. Celgene and our group have since demonstrated that pomalidomide also degrades Ikaros and Aiolos, and breakdown of these neosubstrates upregulates interleukin 2 expression in T-cells.64)

Among thalidomide and its derivatives, only lenalidomide was effective for myelodysplastic syndrome 5q-, a disorder of hematopoietic cells caused by a lack of the long arm of one copy of chromosome 5. Ebert and colleagues found that casein kinase 1 alpha (CK1α), the gene product of CSNK1A, is a lenalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN neosubstrate.65) The CSNK1A gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5. In 5q- cells, CK1α expression levels are lower than in wild-type cells, and lenalidomide effectively decreases CK1α in 5q- cells.

By contrast, thalidomide and pomalidomide have little effect on CK1α. It was shown that breakdown of CK1α mediated by CRL4CRBN activates p53, resulting in antiproliferative effects on 5q- cells.65) This work not only elucidated the molecular basis of the therapeutic effect of lenalidomide on myelodysplastic syndrome 5q- but also suggested that substrate recognition by CRBN is dependent on the structure of CRBN-binding ligands.

Recently, Celgene developed a new CRBN-binding compound CC-885 (Fig. 1D). The structure of CC-885 is similar to that of lenalidomide, but the compound possesses an extended urea and methyl-chloro-phenyl group. Phenotypic screening using more than 100 cell lines showed that CC-885 induces growth defects in various cells, and those derived from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are susceptible to CC-885 treatment. Classical IMiDs such as lenalidomide and pomalidomide are not effective for AML. Therefore, CC-885 represents a new class of CRBN-based anti-AML drugs. AML cells lacking the CRBN gene following editing by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) are insensitive to CC-885, suggesting that the anti-AML effect of this drug is likely to be CRBN-dependent. We identified G1 to S phase transition 1/eukaryotic release factor 1 (GSPT1/eRF3a) as a new neosubstrate of CRL4CRBN in the presence of CC-885 using a coimmunoprecipitation assay.66) GSPT1/eRF3a is a translation termination factor that forms a protein complex with eRF1 and PABP1, and eRF1 binds directly to stop codons.67) GSPT1 is evolutionarily conserved from yeast to human, and lack of GSPT1 leads to G1 arrest.68) Our group and Celgene demonstrated that AML cells expressing CRBN binding-deficient GSPT1 mutants are resistant to CC-885.66) Therefore, we concluded that CC-885 drives the anti-AML effects via breakdown of GSPT1. The effect of CC-885 is based on the degradation of translation termination factors and is not limited to immunomodulation. Therefore, CRBN-binding compounds are now called Cereblon E3 ligase modulators (CELMoDs).30,69) Several CRBN-binding compounds have been reported to induce the breakdown of GSPT1,70,71) and CC-90009, a derivative of CC-885 developed by Celgene, is expected to be clinically effective for treating AML.72)

Recent advances in proteomic analyses have enabled researchers to identify CRBN neosubstrates more efficiently, and many (e.g., ZFP91) have been identified in the presence of CELMoDs.73,74)

Two new CELMoDs, CC-122 (avadomide) and CC-220 (iberdomide), are currently under clinical analysis (Fig. 1E, 1F). Avadomide is effective for the treatment of multiple myeloma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), whereas iberdomide is effective for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).75–81) DLBCL is a malignant type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma derived from B-cells,82) and SLE is an autoimmune disease that causes severe joint pain and fatigue.83) The neosubstrates of CRBN that are responsible for DLBCL and SLE are still unidentified, and identifying them may provide important clues for developing new CELMoDs targeting these diseases.

Structural analysis of CRBN

After the identification of CRBN as a direct target of thalidomide, structural biology research on the precise 3D structure of CRBN has been carried out, and two groups independently determined X-ray crystal structures in 2014.84,85) Thoma and colleagues determined the structure of the chick CRBN-DDB1 complex with thalidomide, and the Celgene group and our group determined the human CRBN-DDB1 structure with lenalidomide. CRBN possesses at least two domains: an N-terminal LON-like domain spanning residues 76–318, which interacts with DDB1, and a thalidomide-binding domain (TBD) spanning residues 319–428. DDB1 possesses three β-propeller (BP) domains (BPA, BPB, and BPC).86) CRBN residues 191–197 also interact with BPC of DDB1, and known substrate receptors such as DDB2 also interact with BPC of DDB1.87) In addition, CRBN residues 221–248 form helices that interact with BPA of DDB1. To the best of our knowledge, CRBN is the first substrate receptor known to bind BPA. TBD has a C4 zinc finger comprising four cysteines (C323, C326, C391, and C394) and a thalidomide pocket composed of three tryptophans (W380, W386, and W400) called the Tri-Trp pocket. The glutarimide moiety is sufficient for binding to the Tri-Trp pocket. The functional significance of the C4 zinc finger motif remains unclear, but it is noteworthy that a recent report showed that the C391R mutant is associated with intellectual disability.88)

In 2016, two groups independently reported the 3D structure of the CRBN/DDB1-ligand-neosusbtrate complex; Thoma and colleagues determined the CRBN/DDB1-lenalidomide-CK1α complex structure,89) and the Celgene group and our group determined the CRBN/DDB1-CC-885-GSPT1 complex structure.66) Two studies revealed that CELMoDs function as a molecular glue between CRBN and neosubstrates, and there is a β-hairpin loop containing a specific glycine in neosubstrates. The glycine (G40 of CK1α, G575 of GSPT1) is essential for the binding of drugs to CRBN. To interact with GSPT1, the extended urea and methyl-chloro-phenyl group of CC-885 is essential, which explains why classical IMiDs do not induce the interaction between CRBN and GSPT1. In 2018, the Thoma group reported the structure of CRBN bound to pomalidomide, and a structural degron C2H2 zinc finger (ZF) motif of Ikaros or ZNF692.74) Ikaros and ZNF692 have a β-hairpin loop that is similar to the surface turn structure of GSPT1 and CK1α. This study revealed the critical amino acid (Q147) of Ikaros that binds to an amino group of pomalidomide.

Thalidomide has a chiral center, hence there are two optical isomers, and it was proposed that (R)-thalidomide has desirable activity whereas (S)-thalidomide has teratogenic activity. However, it was difficult to scrutinize this hypothesis because each isomer is easily racemized (half-life, ∼10 h) in physiological conditions.90) The discovery of CRBN enabled us to verify the proposal using multiple approaches. We conducted structural biological and biochemical studies of (S)- and (R)-enantiomers of thalidomide bound to CRBN.91) X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed that although the (S)-enantiomer binds CRBN in a ‘relaxed’ form that was similar to the free form in water, the conformation of the (R)-enantiomer was twisted during CRBN binding to avoid steric clashes, resulting in a difference in binding activity. The binding affinity of (S)-thalidomide to CRBN was 6- to 10-fold stronger than that of the (R)-enantiomer, and the (S)-enantiomer was a more potent inhibitor of CRBN auto-ubiquitination and more effectively recruited Ikaros to CRBN. Furthermore, we investigated which of the isomers caused thalidomide teratogenicity using zebrafish, and (S)-thalidomide was found to be a potent teratogen, but the (R)-isomer had weaker activity. We concluded that (S)-thalidomide preferentially binds to CRBN, resulting in both therapeutic and teratogenic effects, and (R)-thalidomide is rapidly racemized, and thereby increases the supply of the (S)-enantiomer.

Molecular mechanisms of CRBN-based thalidomide teratogenicity

As described above, our understanding of the mechanism of the therapeutic effects of thalidomide has advanced considerably, but our knowledge of the mechanism of the teratogenic effects remains insufficient. Several cell lines are available for conducting biochemical analyses of myelomas, but it is difficult to adopt such approaches when analyzing developing limbs and ears.

Additionally, when pregnant women take thalidomide during the sensitive period from 20 to 36 days after fertilization, it causes multiple developmental defects to their unborn children, such as limbs that are shorter or completely absent, and malformation of the ears, eyes, and other body parts.92,93) This indicates that thalidomide embryopathy develops in a time- and organ-specific manner, implying multiple actions of thalidomide.

One study found that myeloid ecotropic integration site 2 (MEIS2) is a natural substrate of CRL4CRBN in the absence of CELMoDs.84) MEIS2 is a transcription factor involved in human cardiac and limb development, and ectopic expression inhibits limb outgrowth.84) Thalidomide causes accumulation of MEIS2, suggesting that thalidomide-induced limb deformities are mediated by MEIS2, at least partly. In another study, thalidomide and its derivatives de-stabilized the CD147-MCT1 complex, resulting in multiple effects for these drugs,94) and knockdown of CD147 inhibited fin outgrowth in zebrafish.

Two groups in 2018 independently reported that spalt-like transcription factor 4 (SALL4), a C2H2 zinc finger-containing transcription factor, is likely associated with thalidomide teratogenicity.95,96) The Fischer group performed mass spectrometric analysis of thalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN neosubstrates from human embryonic stem cells and identified SALL4. Meanwhile, Celgene demonstrated that thalidomide treatment of pregnant rabbits downregulated SALL4 in embryos.96) Some mutations of SALL4 are known to be associated with congenital developmental defects such as Duane–Radial–Ray syndrome and Holt–Oran syndrome.97,98) Because these syndromes partly overlap with thalidomide embryopathy,99) SALL4 may be a neosubstrate involved in thalidomide teratogenicity. However, whether thalidomide teratogenicity occurs in animals expressing non-degradable SALL4 has not been determined, hence further analyses of SALL4 and thalidomide are needed.

Our group recently revealed that gene products of TP63 (p63) are involved in ear and limb defects induced by thalidomide.100) The p63 protein belongs to the well-characterized p53 family of tumor suppressors.101)

Aside from its function as a tumor suppressor, p63 plays an important role in limb development. Mutations of the p63 gene cause ectodermal dysplasia and cleft lip/palate syndrome, as well as acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth syndrome.102) There are several isoforms of p63, among which ΔNp63α is essential for limb development, whereas TAp63 is important for cochlea and heart development.103–105) It was found that both ΔNp63 and TAp63 are neosubstrates of thalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN, and thalidomide induced the degradation of ΔNp63, resulting in fin defects mediated through downregulation of FGF8. Degradation of TAp63 induced by thalidomide led to small ear and downregulation of Atoh1, a transcription factor responsible for cochlea development and hearing in zebrafish.105,106) Both thalidomide effects were reversed by the expression of non-degradable mutants ΔNp63 G506A or Tap63 G600A. Therefore, we concluded that p63 proteins are associated with thalidomide teratogenicity.

Although p63-related syndromes such as ectodermal dysplasia and cleft lip/palate syndrome and acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth syndrome, and thalidomide-induced birth defects display a range of clinically overlapping phenotypes, such as limb deformities and hearing impairment, there are certain differences between these disorders. Additional neosubstrates and related factors may explain the discrepancy. In one mouse study, p63-deficient mice exhibited severe limb defects that were reminiscent of thalidomide-induced amelia.103) However, the severely truncated forelimbs of p63-deficient mice were different from the phenotypes commonly seen in p63 syndrome patients such as ectrodactyly, suggesting that the level of residual p63 activity affects the phenotypic severity of the limbs. Further investigations on large mammals such as rabbits or primates expressing non-degradable neosubstrates are clearly needed.

Species-specific effects of thalidomide and its derivatives

Why rodents are resistant to thalidomide is a long-standing question. Of note, thalidomide has neither teratogenic nor therapeutic effects in mice and rats, even though the sequence identity of CRBN between humans and mice is very high (95%). Recently, several groups including ours obtained critical clues for elucidating the species-specific effects of thalidomide. In mouse CRBN, E377 and V388 of human CRBN are replaced with V380 and I391, respectively. Although Ikaros and Aiolos are not decreased by IMiDs such as lenalidomide in wild-type mouse cells, these proteins are degraded in mouse cells expressing human CRBN or the CRBN I391V mutant.65,85) Structural analyses revealed that substitution of V388 with isoleucine leads to steric clashes.65,89) Two groups independently reported transgenic mice expressing CRBN I391V mutants that were susceptible to lenalidomide and pomalidomide.107,108) However, no apparent limb and ear defects occurred in litters when the ‘humanized’ mice were treated with thalidomide, and mouse SALL4 proteins were not degraded by thalidomide in humanized mouse cells. The effects of thalidomide on mouse p63 have not been reported, and expression of not only humanized CRBN but also several humanized neosubstrates may be required to demonstrate thalidomide teratogenicity in rodents. Regarding CC-885, E377 but not V388 is important for inducing GSPT1 degradation.66) Based on the structure of the CRBN-CC-885-GSPT1 complex, the urea part of CC-885 binds to E377. Therefore, it is not surprising that substituting valine at position 388 in CRBN disrupts interactions with CC-885 and GSPT1. Although further investigations are needed, one of the critical reasons for the species-specific effects of thalidomide is subtle amino acid differences between CRBN in different species.

CRBN-based PROTACs

Advances in CRBN analysis have contributed to the development of new protein knockdown technologies32) that can degrade a protein of interest using chemical compounds. In 2001, one group proposed the PROTAC technique,109) and although the first attempt suffered from certain difficulties, improvements have been made subsequently. For example, utilization of ligands of von Hippel Lindau, a substrate receptor of CRL2, achieved the degradation of several proteins of interest such as estrogen receptors. In 2015, Bradner and colleagues developed new heterobifunctional compounds composed of thalidomide and the bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) inhibitor JQ1.110) One of the heterobifunctional molecules, dBET1, is readily degraded by BRD4 in cells expressing CRBN (Fig. 1G). Numerous CRBN-based PROTAC molecules have now been developed for the degradation of various proteins including breakpoint cluster region-abelsonmurine leukemia viral oncogene homolog, Tau, sirtuin 2, viral proteins, and others.111–116) Very recently, one group synthesized CRBN-based PROTAC molecules targeting Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) G12C,117) the degradation of which is beneficial because this KRAS mutation is partly responsible for pancreatic cancers and lung cancers. In reporter cell systems, green fluorescent protein-fused KRAS G12C was successfully degraded by this molecule, but degradation of endogenous KRAS G12C failed in pancreatic cancers.117) Although there are many problems remaining to be solved during PROTAC development, this field will very likely advance in the next few years.118)

Aside from drug development, PROTAC technology can be utilized for basic biology, including analysis of transcription, which is divided into initiation, elongation, and termination. The initiation step of transcription was initially considered the most important, but the elongation step is also critical and can be rate-limiting.119,120) More than 20 years ago, our group identified DRB-sensitivity inducing factor (DSIF) and negative elongation factor as critical transcription elongation factors.121,122) Phosphorylation of DSIF and RNAPI (a subunit of RNA polymerase II) mediated by cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) accelerates transcription elongation, resulting in mRNA production.123,124) BRD4 is also a transcription elongation factor that is believed to recruit CDK9 to DSIF.125) However, protein knockdown using dBET compounds revealed that loss of BRD4 does not directly affect localization of CDK9. Thus, protein knockdown approaches are effective tools for understanding the machinery of biological reactions more deeply.126)

Concluding remarks

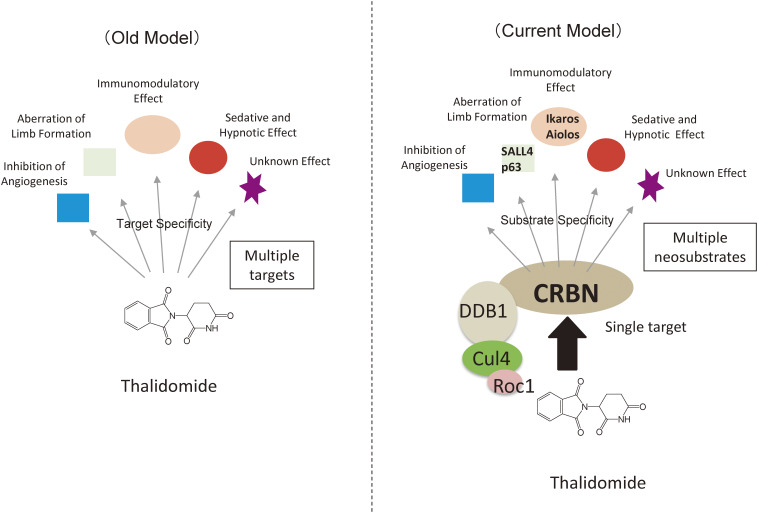

Our discovery of CRBN using the affinity bead technique has enhanced our understanding of the mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives. Researchers originally postulated that thalidomide has multiple target molecules, but most effects of these drugs are dependent on a sole protein, namely CRBN (Fig. 3). Thalidomide and its derivatives have a negligible effect on cells lacking the CRBN gene. However, when a ligand binds to CRBN, the protein is able to recognize many neosubstrates. The therapeutic effect for multiple myeloma is probably based on the degradation of Ikaros and Aiolos, whereas the teratogenic effect is likely to be based on the degradation of SALL4 and p63. New derivatives including PROTAC molecules have been developed, but a new screening system is needed to exclude the possibility that degradation of teratogenic neosubstrates, such as SALL4 and p63, is induced.

Figure 3.

Proposed thalidomide mechanisms of action. Previously, it was thought that thalidomide has multiple targets, resulting in pleiotropic effects. However, it is now believed that thalidomide has a sole target (CRBN). Binding of IMiDs to CRL4CRBN causes breakdown of multiple neosubstrates such as Ikaros and SALL4, resulting in various effects.

Recent studies have shown that degradation of Ikaros and Aiolos is required for the specific E2 enzyme UBE2D3 and the ubiquitin building protein UBE2G1.127,128) The precise regulation of the E3 activity of CRL4CRBN is beginning to be understood.

As mentioned above, the TBD of CRBN is evolutionary highly conserved. The Tri-Trp pocket may bind natural ligands, because recent work showed that uridine (Fig. 1H) and related compounds can bind the Tri-Trp pocket.129,130) However, the physiological significance of such binding remains unknown. Indeed, the functions of CRBN in the ‘absence’ of thalidomide or other ligands is still unclear. Although the development of new medicines targeting CRBN has been the main focus, investigating the basic physiological functions of CRBN is also an attractive field that may open up a completely new area of biological interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (Grant number 17H06112 to H.H., 17H04213 to T.I., and 18H05502 to T.I.). This work was also supported by PRESTO and JST JPMJPR1531 (to T.I.).

Abbreviations

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- BP

β-propeller

- BRD4

bromodomain-containing protein4

- Cas9

CRISPR-associated protein9

- CDK9

cyclin-dependent kinase 9

- CELMoD

Cereblon E3 ligase modulator

- CK1α

casein kinase 1 alpha

- CRBN

cereblon

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- CRL4

cullin-RING ligase-4

- Cul4A

Cullin-4A

- DDB1

damage-specific DNA-binding protein1

- DLBCL

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- DSIF

DRB-sensitivity inducing factor

- E2

ubiquitin conjugating enzyme

- E3

ubiquitin ligase

- eRF3a

eukaryotic release factor1a

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FG

ferrite glycidyl methacrylate

- FGF8

fibroblast growth factor8

- GSPT1

G1 to S phase transition 1

- IMiDs

immunomodulatory imide drugs

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MEIS2

myeloid ecotropic integration site 2

- PROTACs

proteolysis targeting chimeras

- RING

really interesting new gene

- Roc1

Regulator of cullins-1

- SALL4

spalt-like transcription factor4

- SG

styrene glycidyl methacrylate

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TBD

thalidomide-binding domain

Biographies

Profile

Takumi Ito was born in Hokkaido, Japan. He received his BSc in 2004, MEng in 2006, and PhD in Engineering in 2010 from the Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Tokyo Institute of Technology. From 2006 to 2008, he was a JSPS research fellow, and between 2008 and 2012 he was a researcher at the Integrated Research Institute of Tokyo Institute of Technology. From 2012 to 2013, he became an Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology at Tokyo Institute of Technology. Between 2013 and 2016, he was an Assistant Professor at the Department of Nanoparticle Translational Research of Tokyo Medical University, and in 2016, he became an Associate Professor at the same institution. He was a PRESTO researcher from 2015 to 2019. He is now a member of the Department of Chemical Biology of Tokyo Medical University. His current research interests are target isolation of chemical compounds and functional analysis of cereblon, a direct target of thalidomide. He received the Tejima Memorial Research Award in 2011, the Inoue Research Award for Young Scientists in 2012, and the Sassa Memorial Award in 2017.

Hiroshi Handa was born in Oita Prefecture in 1946. He graduated from Keio University School of Medicine in 1972, and received his MD and PhD from Keio University Graduate School of Medicine in 1976. He was appointed as an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo in 1976. He then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1978 to 1980. He was appointed as an Associate Professor at the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo in 1984, and moved to the University of Tokyo as an Associate Professor in 1987. He was appointed as a Professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1991. Since 2012, he has been a Professor at Tokyo Medical University and an Emeritus Professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology. He has successfully completed several government-funded research projects as a project leader. His notable achievements include the discovery of the negative transcription elongation factors, DRB sensitivity-inducing factor and negative elongation factor, which bind to RNA polymerase II and regulate the rate of transcription elongation, including promoter proximal pausing. He also identified cereblon (CRBN) as the target of thalidomide teratogenicity, using the original affinity nanobead technology that he developed, and further demonstrated the involvement of CRBN in the anticancer effects of thalidomide, and the mechanisms of the main and side effects of thalidomide and its derivatives. These findings then subsequently led to the development of novel drugs, including CRBN E3 ligase modulators and CRBN-based proteolysis targeting chimeras. He has received several awards for his accomplishments, including the Kitasato Award and the Shimadzu Award.

References

- 1).McBride W.G. (1977) Thalidomide embryopathy. Teratology 16, 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Franks M.E., Macpherson G.R., Figg W.D. (2004) Thalidomide. Lancet 363, 1802–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Melchert M., List A. (2007) The thalidomide saga. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Sheskin J. (1965) Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 6, 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Gutierrez-Rodriguez O. (1984) Thalidomide. A promising new treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 27, 1118–1121.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Vogelsang G.B., Hess A.D., Santos G.W. (1988) Thalidomide for treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 3, 393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Vogelsang G.B., Farmer E.R., Hess A.D., Altamonte V., Beschorner W.E., Jabs D.A., et al. (1992) Thalidomide for the treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 326, 1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Sampaio E.P., Sarno E.N., Galilly R., Cohn Z.A., Kaplan G. (1991) Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 173, 699–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Moreira A.L., Sampaio E.P., Zmuidzinas A., Frindt P., Smith K.A., Kaplan G. (1993) Thalidomide exerts its inhibitory action on tumor necrosis factor alpha by enhancing mRNA degradation. J. Exp. Med. 177, 1675–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).D’Amato R.J., Loughnan M.S., Flynn E., Folkman J. (1994) Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 4082–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Singhal S., Mehta J., Desikan R., Ayers D., Roberson P., Eddlemon P., et al. (1999) Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1565–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Zeldis J.B., Williams B.A., Thomas S.D., Elsayed M.E. (1999) S.T.E.P.S.: A comprehensive program for controlling and monitoring access to thalidomide. Clin. Ther. 21, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Ooba N., Sato T., Watanabe H., Kubota K. (2010) Resolving a double standard for risk management of thalidomide: An evaluation of two different risk management programmes in Japan. Drug Saf. 33, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Muller G.W., Chen R., Huang S.Y., Corral L.G., Wong L.M., Patterson R.T., et al. (1999) Amino-substituted thalidomide analogs: Potent inhibitors of TNF-α production. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 1625–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Bartlett J.B., Dredge K., Dalgleish A.G. (2004) The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).List A., Kurtin S., Roe D.J., Buresh A., Mahadevan D., Fuchs D., et al. (2005) Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).List A., Dewald G., Bennett J., Giagounidis A., Raza A., Feldman E., et al. (2006) Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Dimopoulos M., Spencer A., Attal M., Prince H.M., Harousseau J.L., Dmoszynska A., et al. (2007) Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2123–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Habermann T.M., Lossos I.S., Justice G., Vose J.M., Wiernik P.H., McBride K., et al. (2009) Lenalidomide oral monotherapy produces a high response rate in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 145, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Ruan J., Martin P., Shah B., Schuster S.J., Smith S.M., Furman R.R., et al. (2015) Lenalidomide plus Rituximab as initial treatment for mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1835–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Ramsay A.G., Clear A.J., Kelly G., Fatah R., Matthews J., Macdougall F., et al. (2009) Follicular lymphoma cells induce T-cell immunologic synapse dysfunction that can be repaired with lenalidomide: Implications for the tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. Blood 114, 4713–4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Morschhauser F., Fowler N.H., Feugier P., Bouabdallah R., Tilly H., Palomba M.L., et al. (2018) Rituximab plus lenalidomide in advanced untreated follicular lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Shimizu N., Sugimoto K., Tang J., Nishi T., Sato I., Hiramoto M., et al. (2000) High-performance affinity beads for identifying drug receptors. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 877–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Nishio K., Masaike Y., Ikeda M., Narimatsu H., Gokon N., Tsubouchi S., et al. (2008) Development of novel magnetic nano-carriers for high-performance affinity purification. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 64, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Ito T., Ando H., Suzuki T., Ogura T., Hotta K., Imamura Y., et al. (2010) Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science 327, 1345–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Ito T., Handa H. (2015) Myeloid disease: Another action of a thalidomide derivative. Nature 523, 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Asatsuma-Okumura T., Ito T., Handa H. (2019) Molecular mechanisms of cereblon-based drugs. Pharmacol. Ther. 202, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Petroski M.D., Deshaies R.J. (2005) Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Angers S., Li T., Yi X., MacCoss M.J., Moon R.T., Zheng N. (2006) Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1-CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature 443, 590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Chamberlain P.P., Cathers B.E. (2019) Cereblon modulators: Low molecular weight inducers of protein degradation. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 31, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Deshaies R.J. (2015) Protein degradation: Prime time for PROTACs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 634–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Lai A.C., Crews C.M. (2016) Induced protein degradation: An emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Kubota K., Funabashi M., Ogura Y. (2019) Target deconvolution from phenotype-based drug discovery by using chemical proteomics approaches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1867, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Briggs M.R., Kadonaga J.T., Bell S.P., Tjian R. (1986) Purification and biochemical characterization of the promoter-specific transcription factor, Sp1. Science 234, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Uga H., Kuramori C., Ohta A., Tsuboi Y., Tanaka H., Hatakeyama M., et al. (2006) A new mechanism of methotrexate action revealed by target screening with affinity beads. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Kabe Y., Ohmori M., Shinouchi K., Tsuboi Y., Hirao S., Azuma M., et al. (2006) Porphyrin accumulation in mitochondria is mediated by 2-oxoglutarate carrier. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31729–31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Iizumi Y., Sagara H., Kabe Y., Azuma M., Kume K., Ogawa M., et al. (2007) The enteropathogenic E. coli effector EspB facilitates microvillus effacing and antiphagocytosis by inhibiting myosin function. Cell Host Microbe 2, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Yoshida M., Kabe Y., Wada T., Asai A., Handa H. (2008) A new mechanism of 6-((2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-7H-indeno(2,1-c)quinolin-7-one dihydrochloride (TAS-103) action discovered by target screening with drug-immobilized affinity beads. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Azuma M., Kabe Y., Kuramori C., Kondo M., Yamaguchi Y., Handa H. (2008) Adenine nucleotide translocator transports haem precursors into mitochondria. PLoS One 3, e3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Kuramori C., Hase Y., Hoshikawa K., Watanabe K., Nishi T., Hishiki T., et al. (2009) Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate targets glycogen debranching enzyme and affects glycogen metabolism in rat testis. Toxicol. Sci. 109, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Kume K., Iizumi Y., Shimada M., Ito Y., Kishi T., Yamaguchi Y., et al. (2010) Role of N-end rule ubiquitin ligases UBR1 and UBR2 in regulating the leucine-mTOR signaling pathway. Genes Cells 15, 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Ito Y., Ito T., Karasawa S., Enomoto T., Nashimoto A., Hase Y., et al. (2012) Identification of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) as a novel target of bisphenol A. PLoS One 7, e50481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Sakamoto S., Hatakeyama M., Ito T., Handa H. (2012) Tools and methodologies capable of isolating and identifying a target molecule for a bioactive compound. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 1990–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Karasawa S., Azuma M., Kasama T., Sakamoto S., Kabe Y., Imai T., et al. (2013) Vitamin K2 covalently binds to Bak and induces Bak-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 83, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Kabe Y., Nakane T., Koike I., Yamamoto T., Sugiura Y., Harada E., et al. (2016) Haem-dependent dimerization of PGRMC1/Sigma-2 receptor facilitates cancer proliferation and chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 7, 11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Higgins J.J., Pucilowska J., Lombardi R.Q., Rooney J.P. (2004) A mutation in a novel ATP-dependent Lon protease gene in a kindred with mild mental retardation. Neurology 63, 1927–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Wittschieben B.O., Wood R.D. (2003) DDB complexities. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2, 1065–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Iovine B., Iannella M.L., Bevilacqua M.A. (2011) Damage-specific DNA binding protein 1 (DDB1): A protein with a wide range of functions. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 1664–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Pickart C.M. (2004) Back to the future with ubiquitin. Cell 116, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Hotton S.K., Callis J. (2008) Regulation of cullin RING ligases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 467–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Lee J., Zhou P. (2007) DCAFs, the missing link of the CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 26, 775–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Sugasawa K., Okuda Y., Saijo M., Nishi R., Matsuda N., Chu G., et al. (2005) UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex. Cell 121, 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Jin J., Arias E.E., Chen J., Harper J.W., Walter J.C. (2006) A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol. Cell 23, 709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Groisman R., Polanowska J., Kuraoka I., Sawada J., Saijo M., Drapkin R., et al. (2003) The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell 113, 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Lieschke G.J., Currie P.D. (2007) Animal models of human disease: Zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 353–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Lewandoski M., Sun X., Martin G.R. (2000) Fgf8 signalling from the AER is essential for normal limb development. Nat. Genet. 26, 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57).Moon A.M., Capecchi M.R. (2000) Fgf8 is required for outgrowth and patterning of the limbs. Nat. Genet. 26, 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58).Hansen J.M., Gong S.G., Philbert M., Harris C. (2002) Misregulation of gene expression in the redox-sensitive NF-kappab-dependent limb outgrowth pathway by thalidomide. Dev. Dyn. 225, 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59).Lopez-Girona A., Heintel D., Zhang L.H., Mendy D., Gaidarova S., Brady H., et al. (2011) Lenalidomide downregulates the cell survival factor, interferon regulatory factor-4, providing a potential mechanistic link for predicting response. Br. J. Haematol. 154, 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60).Zhu Y.X., Braggio E., Shi C.X., Bruins L.A., Schmidt J.E., Van Wier S., et al. (2011) Cereblon expression is required for the antimyeloma activity of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Blood 118, 4771–4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Lopez-Girona A., Mendy D., Ito T., Miller K., Gandhi A.K., Kang J., et al. (2012) Cereblon is a direct protein target for immunomodulatory and antiproliferative activities of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Leukemia 26, 2326–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62).Kronke J., Udeshi N.D., Narla A., Grauman P., Hurst S.N., McConkey M., et al. (2014) Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science 343, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63).Lu G., Middleton R.E., Sun H., Naniong M., Ott C.J., Mitsiades C.S., et al. (2014) The myeloma drug lenalidomide promotes the cereblon-dependent destruction of Ikaros proteins. Science 343, 305–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64).Gandhi A.K., Kang J., Havens C.G., Conklin T., Ning Y., Wu L., et al. (2014) Immunomodulatory agents lenalidomide and pomalidomide co-stimulate T cells by inducing degradation of T cell repressors Ikaros and Aiolos via modulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4CRBN. Br. J. Haematol. 164, 811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65).Kronke J., Fink E.C., Hollenbach P.W., MacBeth K.J., Hurst S.N., Udeshi N.D., et al. (2015) Lenalidomide induces ubiquitination and degradation of CK1α in del(5q) MDS. Nature 523, 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66).Matyskiela M.E., Lu G., Ito T., Pagarigan B., Lu C.C., Miller K., et al. (2016) A novel cereblon modulator recruits GSPT1 to the CRL4CRBN ubiquitin ligase. Nature 535, 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67).Cheng Z., Saito K., Pisarev A.V., Wada M., Pisareva V.P., Pestova T.V., et al. (2009) Structural insights into eRF3 and stop codon recognition by eRF1. Genes Dev. 23, 1106–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68).Kikuchi Y., Shimatake H., Kikuchi A. (1988) A yeast gene required for the G1-to-S transition encodes a protein containing an A-kinase target site and GTPase domain. EMBO J. 7, 1175–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69).Chamberlain P.P., Hamann L.G. (2019) Development of targeted protein degradation therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70).Hansen J.D., Condroski K., Correa M., Muller G., Man H.W., Ruchelman A., et al. (2018) Protein degradation via CRL4CRBN ubiquitin ligase: Discovery and structure-activity relationships of novel glutarimide analogs that promote degradation of Aiolos and/or GSPT1. J. Med. Chem. 61, 492–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71).Ishoey M., Chorn S., Singh N., Jaeger M.G., Brand M., Paulk J., et al. (2018) Translation termination factor GSPT1 is a phenotypically relevant off-target of heterobifunctional phthalimide degraders. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72).Lu G., Surka C., Lu C.C., Jang I.S., Wang K., Rolfe M. (2019) Elucidating the mechanism of action of CC-90009, a novel cereblon E3 ligase modulator, in AML via genome-wide CRISPR screen. Blood 134 (Suppl. 1), 405. [Google Scholar]

- 73).An J., Ponthier C.M., Sack R., Seebacher J., Stadler M.B., Donovan K.A., et al. (2017) pSILAC mass spectrometry reveals ZFP91 as IMiD-dependent substrate of the CRL4CRBN ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Commun. 8, 15398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74).Sievers Q.L., Petzold G., Bunker R.D., Renneville A., Slabicki M., Liddicoat B.J., et al. (2018) Defining the human C2H2 zinc finger degrome targeted by thalidomide analogs through CRBN. Science 362, eaat0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75).Hagner P.R., Man H.W., Fontanillo C., Wang M., Couto S., Breider M., et al. (2015) CC-122, a pleiotropic pathway modifier, mimics an interferon response and has antitumor activity in DLBCL. Blood 126, 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76).Cubillos-Zapata C., Cordoba R., Avendano-Ortiz J., Lopez-Collazo E. (2017) Thalidomide analog CC-122 induces a refractory state in monocytes from patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 58, 1999–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77).Rasco D.W., Papadopoulos K.P., Pourdehnad M., Gandhi A.K., Hagner P.R., Li Y., et al. (2019) A first-in-human study of novel cereblon modulator avadomide (CC-122) in advanced malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78).Carpio C., Bouabdallah R., Ysebaert L., Sancho J.M., Salles G.A., Cordoba R., et al. (2020) Avadomide monotherapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL: Safety, efficacy, and a predictive gene classifier. Blood 135, 996–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79).Matyskiela M.E., Zhang W., Man H.W., Muller G., Khambatta G., Baculi F., et al. (2018) A cereblon modulator (CC-220) with improved degradation of Ikaros and Aiolos. J. Med. Chem. 61, 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80).Schafer P.H., Ye Y., Wu L., Kosek J., Ringheim G., Yang Z., et al. (2018) Cereblon modulator iberdomide induces degradation of the transcription factors Ikaros and Aiolos: Immunomodulation in healthy volunteers and relevance to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 1516–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81).Bjorklund C.C., Kang J., Amatangelo M., Polonskaia A., Katz M., Chiu H., et al. (2020) Iberdomide (CC-220) is a potent cereblon E3 ligase modulator with antitumor and immunostimulatory activities in lenalidomide- and pomalidomide-resistant multiple myeloma cells with dysregulated CRBN. Leukemia 34, 1197–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82).Tilly H., Gomes da Silva M., Vitolo U., Jack A., Meignan M., Lopez-Guillermo A., et al. (2015) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 26 (Suppl. 5), v116–v125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83).Pons-Estel G.J., Ugarte-Gil M.F., Alarcon G.S. (2017) Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 13, 799–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84).Fischer E.S., Bohm K., Lydeard J.R., Yang H., Stadler M.B., Cavadini S., et al. (2014) Structure of the DDB1-CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase in complex with thalidomide. Nature 512, 49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85).Chamberlain P.P., Lopez-Girona A., Miller K., Carmel G., Pagarigan B., Chie-Leon B., et al. (2014) Structure of the human Cereblon-DDB1-lenalidomide complex reveals basis for responsiveness to thalidomide analogs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86).Li T., Chen X., Garbutt K.C., Zhou P., Zheng N. (2006) Structure of DDB1 in complex with a paramyxovirus V protein: Viral hijack of a propeller cluster in ubiquitin ligase. Cell 124, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87).Scrima A., Konickova R., Czyzewski B.K., Kawasaki Y., Jeffrey P.D., Groisman R., et al. (2008) Structural basis of UV DNA-damage recognition by the DDB1-DDB2 complex. Cell 135, 1213–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88).Sheereen A., Alaamery M., Bawazeer S., Al Yafee Y., Massadeh S., Eyaid W. (2017) A missense mutation in the CRBN gene that segregates with intellectual disability and self-mutilating behaviour in a consanguineous Saudi family. J. Med. Genet. 54, 236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89).Petzold G., Fischer E.S., Thoma N.H. (2016) Structural basis of lenalidomide-induced CK1α degradation by the CRL4CRBN ubiquitin ligase. Nature 532, 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90).Nishimura K., Hashimoto Y., Iwasaki S. (1994) (S)-form of α-methyl-N(α)-phthalimidoglutarimide, but not its (R)-form, enhanced phorbol ester-induced tumor necrosis factor-α production by human leukemia cell HL-60: Implication of optical resolution of thalidomidal effects. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 42, 1157–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91).Mori T., Ito T., Liu S., Ando H., Sakamoto S., Yamaguchi Y., et al. (2018) Structural basis of thalidomide enantiomer binding to cereblon. Sci. Rep. 8, 1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92).Vargesson N. (2009) Thalidomide-induced limb defects: Resolving a 50-year-old puzzle. Bioessays 31, 1327–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93).Vargesson N. (2015) Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 105, 140–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94).Eichner R., Heider M., Fernandez-Saiz V., van Bebber F., Garz A.K., Lemeer S., et al. (2016) Immunomodulatory drugs disrupt the cereblon-CD147-MCT1 axis to exert antitumor activity and teratogenicity. Nat. Med. 22, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95).Donovan K.A., An J., Nowak R.P., Yuan J.C., Fink E.C., Berry B.C., et al. (2018) Thalidomide promotes degradation of SALL4, a transcription factor implicated in Duane Radial Ray syndrome. Elife 7, e38430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96).Matyskiela M.E., Couto S., Zheng X., Lu G., Hui J., Stamp K., et al. (2018) SALL4 mediates teratogenicity as a thalidomide-dependent cereblon substrate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97).Al-Baradie R., Yamada K., St. Hilaire C., Chan W.M., Andrews C., McIntosh N., et al. (2002) Duane radial ray syndrome (Okihiro syndrome) maps to 20q13 and results from mutations in SALL4, a new member of the SAL family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1195–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98).Kohlhase J., Heinrich M., Schubert L., Liebers M., Kispert A., Laccone F., et al. (2002) Okihiro syndrome is caused by SALL4 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2979–2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99).Kohlhase J., Holmes L.B. (2004) Mutations in SALL4 in malformed father and daughter postulated previously due to reflect mutagenesis by thalidomide. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 70, 550–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100).Asatsuma-Okumura T., Ando H., De Simone M., Yamamoto J., Sato T., Shimizu N., et al. (2019) p63 is a cereblon substrate involved in thalidomide teratogenicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 1077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101).Yang A., Kaghad M., Caput D., McKeon F. (2002) On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 18, 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102).Rinne T., Hamel B., van Bokhoven H., Brunner H.G. (2006) Pattern of p63 mutations and their phenotypes—Update. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 140, 1396–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103).Mills A.A., Zheng B., Wang X.J., Vogel H., Roop D.R., Bradley A. (1999) p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398, 708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104).Rouleau M., Medawar A., Hamon L., Shivtiel S., Wolchinsky Z., Zhou H., et al. (2011) TAp63 is important for cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells and heart development. Stem Cells 29, 1672–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105).Terrinoni A., Serra V., Bruno E., Strasser A., Valente E., Flores E.R., et al. (2013) Role of p63 and the Notch pathway in cochlea development and sensorineural deafness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 7300–7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106).Millimaki B.B., Sweet E.M., Dhason M.S., Riley B.B. (2007) Zebrafish atoh1 genes: Classic proneural activity in the inner ear and regulation by Fgf and Notch. Development 134, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107).Fink E.C., McConkey M., Adams D.N., Haldar S.D., Kennedy J.A., Guirguis A.A., et al. (2018) CrbnI391V is sufficient to confer in vivo sensitivity to thalidomide and its derivatives in mice. Blood 132, 1535–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108).Gemechu Y., Millrine D., Hashimoto S., Prakash J., Sanchenkova K., Metwally H., et al. (2018) Humanized cereblon mice revealed two distinct therapeutic pathways of immunomodulatory drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 11802–11807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109).Sakamoto K.M., Kim K.B., Kumagai A., Mercurio F., Crews C.M., Deshaies R.J. (2001) Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1–Cullin–F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8554–8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110).Winter G.E., Buckley D.L., Paulk J., Roberts J.M., Souza A., Dhe-Paganon S., et al. (2015) Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science 348, 1376–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111).Lai A.C., Toure M., Hellerschmied D., Salami J., Jaime-Figueroa S., Ko E., et al. (2016) Modular PROTAC design for the degradation of oncogenic BCR-ABL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 807–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112).Robb C.M., Contreras J.I., Kour S., Taylor M.A., Abid M., Sonawane Y.A., et al. (2017) Chemically induced degradation of CDK9 by a proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC). Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 53, 7577–7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113).Olson C.M., Jiang B., Erb M.A., Liang Y., Doctor Z.M., Zhang Z., et al. (2018) Pharmacological perturbation of CDK9 using selective CDK9 inhibition or degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114).Schiedel M., Herp D., Hammelmann S., Swyter S., Lehotzky A., Robaa D., et al. (2018) Chemically induced degradation of sirtuin 2 (Sirt2) by a proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) based on sirtuin rearranging ligands (SirReals). J. Med. Chem. 61, 482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115).de Wispelaere M., Du G., Donovan K.A., Zhang T., Eleuteri N.A., Yuan J.C., et al. (2019) Small molecule degraders of the hepatitis C virus protease reduce susceptibility to resistance mutations. Nat. Commun. 10, 3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116).Silva M.C., Ferguson F.M., Cai Q., Donovan K.A., Nandi G., Patnaik D., et al. (2019) Targeted degradation of aberrant tau in frontotemporal dementia patient-derived neuronal cell models. Elife 8, e45457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117).Zeng M., Xiong Y., Safaee N., Nowak R.P., Donovan K.A., Yuan C.J., et al. (2020) Exploring targeted degradation strategy for oncogenic KRAS(G12C). Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 19–31.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118).Chamberlain P.P., D’Agostino L.A., Ellis J.M., Hansen J.D., Matyskiela M.E., McDonald J.J., et al. (2019) Evolution of cereblon-mediated protein degradation as a therapeutic modality. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1592–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119).Krumm A., Hickey L.B., Groudine M. (1995) Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II defines a general rate-limiting step after transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 9, 559–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120).Adelman K., Lis J.T. (2012) Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: Emerging roles in metazoans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 720–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121).Wada T., Takagi T., Yamaguchi Y., Ferdous A., Imai T., Hirose S., et al. (1998) DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 12, 343–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122).Yamaguchi Y., Takagi T., Wada T., Yano K., Furuya A., Sugimoto S., et al. (1999) NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell 97, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123).Marshall N.F., Price D.H. (1995) Purification of P-TEFb, a transcription factor required for the transition into productive elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12335–12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124).Yamada T., Yamaguchi Y., Inukai N., Okamoto S., Mura T., Handa H. (2006) P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-terminal repeats is critical for processive transcription elongation. Mol. Cell 21, 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125).Patel M.C., Debrosse M., Smith M., Dey A., Huynh W., Sarai N., et al. (2013) BRD4 coordinates recruitment of pause release factor P-TEFb and the pausing complex NELF/DSIF to regulate transcription elongation of interferon-stimulated genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2497–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126).Winter G.E., Mayer A., Buckley D.L., Erb M.A., Roderick J.E., Vittori S., et al. (2017) BET bromodomain proteins function as master transcription elongation factors independent of CDK9 recruitment. Mol. Cell 67, 5–18.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127).Lu G., Weng S., Matyskiela M., Zheng X., Fang W., Wood S., et al. (2018) UBE2G1 governs the destruction of cereblon neomorphic substrates. Elife 7, e40958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128).Sievers Q.L., Gasser J.A., Cowley G.S., Fischer E.S., Ebert B.L. (2018) Genome-wide screen identifies cullin-RING ligase machinery required for lenalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN activity. Blood 132, 1293–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129).Hartmann M.D., Boichenko I., Coles M., Zanini F., Lupas A.N., Hernandez Alvarez B. (2014) Thalidomide mimics uridine binding to an aromatic cage in cereblon. J. Struct. Biol. 188, 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130).Boichenko I., Bar K., Deiss S., Heim C., Albrecht R., Lupas A.N., et al. (2018) Chemical ligand space of cereblon. ACS Omega 3, 11163–11171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]