Abstract

Reflexivity has emerged as a key concept in the field of health promotion (HP). Yet it remains unclear how diverse forms of reflexivity are specifically relevant to HP concerns, and how these “reflexivities” are interconnected. We argue that frameworks are needed to support more systematic integration of reflexivity in HP training and practice. In this article, we propose a typology of reflexivity in HP to facilitate the understanding of reflexivity in professional training. Drawing from key theories and models of reflexivity, this typology proposes three reflexive positions (ideal-types) with specific purposes for HP: reflexivity in, on, and underlying action. This article illustrates our typology’s ideal-types with vignettes collected from HP actors working with reflexivity in North America and Europe. We suggest that our typology constitutes a conceptual device to organize and discuss a variety of experiences of engaging with reflexivity for HP. We propose the typology may support integrating reflexivity as a key feature in training a future cadre of health promoters and as a means for building a responsible HP practice.

Keywords: reflexivity, health promotion, ideal-types, reflexive practice, training

Introduction

Reflexivity in Health Promotion

Over the past decade, reflexivity has emerged as a key concept for the field of health promotion (HP) as evidenced by a growing body of literature on reflexivity in the field (Bisset et al., 2017; Boutilier & Mason, 2017; Fleming, 2007; Issitt, 2003; Johnson & MacDougall, 2007; Potvin & McQueen, 2007; Tremblay et al., 2014; Tretheway et al., 2015). Reflexivity has been examined and hailed as a means of developing alternative modes of thinking about HP and of engaging in HP research and practice with the aim of addressing a broad range of issues that have been deemed central to the field by the Ottawa Charter, such as social inequities, social justice, power dynamics, globalized health concerns, and the advancement of context-driven and settings-based interventions (Caplan, 1993; Eakin et al., 1996; Kickbusch, 2007; Shareck et al., 2013; Tretheway et al., 2015). Given the explicit call from within the field of HP to examine these issues as well as the assumptions and politics underlying HP to develop new perspectives for action (Kickbusch, 2007), reflexivity appears increasingly relevant for HP (Tretheway et al., 2015). However, despite its growing popularity and promise, it remains unclear how reflexivity can be conceptualized in relationship to HP concerns, and how it can become integrated into HP training.

Drawing on major works on reflexivity (Boud et al., 1985; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992; Boutilier & Mason, 2017; Mezirow, 1990; Schön, 1991), we developed a shared understanding to agree on a broad definition of reflexivity as

an intentional intellectual activity in which individuals explore or examine a situation, an issue, or object on the basis of their past experiences, to develop new understandings that will ultimately influence their actions or in which they critically analyze the field of action as a whole. (Tremblay et al., 2014, p. 539)

In this article, we employ action as an inclusive term for the range of activities carried out by HP actors, including research, intervention, evaluation, practice, or policymaking. Since reflexivity is defined both according to its links to practice and to broader critical examinations of the field, it holds promise for guiding our thinking to better adapt to complex and contextually situated health issues and unexpected situations of HP practice that cannot be anticipated in formal training (Kickbusch, 2007). HP actors face increasingly complex health challenges, resulting from numerous contemporary concerns, including the globalization of health problems and their determinants (Labonte et al., 2011), unanticipated and undesirable consequences of interventions (Allen-Scott et al., 2014) and the continuous modification of social practices by the very knowledge they produce (Potvin & McQueen, 2007). Already in the early 2000s, Issitt (2003) argued that health promoters ought to draw on reflexivity “to evaluate the possibilities and limitations of their own values and actions in relation to the ‘macro’ political context in which they are operating, and the challenges they face personally and professionally in tackling health inequities” (p. 175). Kickbusch (2007) has also suggested that engaging with reflexivity in health research and action may be critical, especially in a world in which there are increasing “options, choices and insecurity” (p. 152) regarding health and in which traditional “knowledge no longer means certitude” (p. 153). The inclusion of reflexivity in HP thus has potential to improve contemporary HP research and action (i.e., anti-oppressive health practices) and could be a means to highlight power relationships within HP interventions (Fleming, 2007; Kippax & Kinder, 2002; Labonte, 1994; Tremblay et al., 2014), thereby fostering the type of change to which HP was originally committed (Eakin et al., 1996; Issitt, 2003).

Why We Need a Framework for Reflexivity in HP Training

Despite broad recognition that reflexivity is important for the field of HP, how to develop and foster frameworks for integrating and engaging different forms of reflexivity as part of HP training remains largely unexplored (Mann et al., 2009; Tremblay et al., 2014). For instance, HP actors do not have a common vocabulary or conceptual apparatus specific to the field that can be used to think and talk about their reflexive endeavors as integral to their work. As such, discussions and instances of engaging in reflexivity within the field of HP are somewhat dispersed and draw on quite disparate conceptualizations of reflection and reflexivity. In addition, frameworks of reflexivity proposed in the field are still nascent and create confusion by considering reflexivity as a means to achieve health equity in HP action rather than an end in itself (Guichard et al., 2019; Masuda et al., 2014; Tremblay et al., 2014). This dispersion also results in difficulty introducing and integrating reflexivity into HP training.

While some recent attempts have been made to concretely link HP core competencies to reflexivity (Wigginton et al., 2019), we argue that new approaches and tools are needed to support a more systematic integration and coherent discussion of the role and uses of reflexivity in HP training and practice. Rather than advocating for one model of reflexivity or making hard distinctions between the different “reflexivities”, we think that these different forms of reflexivity can be placed within a continuum of reflexivity for HP. In this article, we propose a typology-based tool to assist the understanding of reflexivity in HP training. Borrowing from key theories and models of reflexivity, this framework articulates coherently three different reflexive positions and their purposes for HP training and practice, while emphasizing their inherent connectedness. To position this framework concretely within HP practice, we propose that reflexivity should be discussed in relationship to foundational documents of the field, such as the Ottawa Charter, in order to facilitate the integration of reflexivity in HP training and professional education. Furthermore, to facilitate its use, we have developed a set of question as prompts for each of the three reflexive positions to create a starting point for integrating reflexivity in HP practice.

Ideal-Types Of Reflexivity In Health Promotion

With the aforementioned definition as our starting point, our integrated typology for reflexive experiences in HP differentiates three broad reflexive exercises in which HP actors’ experiences can be positioned. Concretely, we call these reflexivities “ideal-types,” which represent syntheses of multidisciplinary perspectives on reflexivity (see Table 1). We consider the ideal-types as mileposts in the landscape of reflexivity where HP actors may consider situating their work, and as conceptual tools that can be used to discuss and compare experiences of reflexivity in different HP contexts. As such, the ideal-types are not intended to correspond to strict categories of empirical realities, but when applied to experiences they can elicit reflection and discussion on their main characteristics, and evoke consideration about the fuzziness (or fluidity) between them. The ideal-types are organized according to an actor’s position, proximity, and perspective in terms of her or his relationship to HP action.

Table 1.

Typology: Three Ideal-Types of Reflexivity in HP

| Types | Definitions | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Reflexivity in actiona | The actor(s) examine(s) experiences and situations in their own action(s), and make(s) adjustments while in the midst of “doing” the action. This entails an effort to create meaning or make sense of the action being conducted. Being reflexive in action allows actors to mobilize knowledge emerging during action. | - What am I learning about this

practice/phenomenon/population right now, and how

might this learning affect or shape the next steps

of the action being undertaken? - How can I/we integrate this new knowledge and adjust the action to better suit/adapt to an evolving situation? |

| Reflexivity on actiona | The actor(s) examine(s) action(s) after experiences and situations have taken place. This entails reflection on how the action was designed and implemented, and on the methods and strategies used to carry out the action. Being reflexive on action allows for actors to produce knowledge emerging from action and for future action. | - What could I/we have done

differently? ○ In hindsight, how well was the health promotion action suited to the needs and context of the situation/population in terms of strategy, design, and implementation? ○ Did the health promotion action permit achieving the expected results? ○ Were there unexpected effects? ○ With the experience and knowledge gained, what would I/we do differently to better take the situation, the population and their history, perspectives, needs, and experiences into account in the design and implementation? |

| Reflexivity underlying actiona | The actor(s) critically question(s) the premises of the field of action including the power dynamics, the political and cultural values, and any other underlying assumptions. Being reflexive about what is underlying action may be part of a larger systemic change process that creates awareness about the field of action at large and encourages alternative perspectives for action and for evaluation. | - What values, beliefs, and assumptions underlie

my/our action, and more generally, the work done

in the field of HP in this

setting/context? - What power structures might this kind of practice/action be creating, supporting, or modifying? - What forms of knowledge does this practice/action draw on and give validity to, and inversely, what forms of knowledge might it be invalidating or marginalizing? |

“Action” is an inclusive term for the range of activities carried out by health promotion actors including research, intervention, evaluation, practice, or policy.

The first ideal-type, reflexivity in action, relates to the reflexive process during the action being undertaken, wherein practitioners and researchers engage in reflection while in the process of “doing” the action and adjust their practices accordingly. Reflexivity in action, as similarly outlined by Schön (1991) for educational practice, occurs when the practitioner “reflects on the phenomenon before him, and on the prior understandings . . . which serves to generate both a new understanding of the phenomenon and a change in the situation” (p. 68). With this in mind, reflexivity in action linked to professional practice, can occur from various vantage points within HP action (practice and research); but it is always linked to the adjustment of practices that are taking place at a given moment. Guiding question prompts for this ideal-type include the following: (a) What am I learning about this practice/phenomenon/population right now, and how might this learning affect or shape the next steps of the action being undertaken? (b) How can I/we integrate this new knowledge and adjust the action to better suit/adapt to an evolving situation?

The second ideal-type, reflexivity on action, is a form of reflexivity that entails stepping back and questioning one’s own (or a group’s) concrete actions once completed. At this level, reflexivity occurs after a particular action has been carried out, and when there is some temporal distance between the actor(s) and the action. This reflexivity distinguishes itself by having the pragmatic or mechanistic elements of the action as its focus. It emphasizes a critical reflection about the design and implementation of an action, and on the methods and strategies applied for carrying out the action. Reflexivity on action lies at the border between the first and the third ideal-types. Overall, this kind of “post-action” reflexivity is focused on the technical improvement of practices. In the words of Teekman (2000), this kind of reflexivity focuses “on learning, on the development of practice knowing/knowledge” (p. 1127). A first broad question for this ideal-type might include the following: (a) What could I/we have done differently? Other subquestions would include (b) In hindsight, how well was the HP action suited to the needs and context of the situation/population in terms of strategy, design and implementation? (c) Did the HP action permit achieving the expected results? (d) Were there any unexpected effects? (e) With the experience and knowledge gained, what would I/we do differently to better take the situation, the population and their history, perspectives, needs, and experiences into account in the design and implementation?

The third ideal-type, reflexivity underlying action, has a distinctly broader scope, and entails a critical questioning of the premises of the action and the field of action as a whole. This reflexivity involves questioning the power dynamics that are implicit in a field of action, or highlighting the assumptions that underlie a field of research, or examining various influences that shape the objects of interest to these fields (i.e., health). Bolam and Chamberlain (2003) (who call this “dark reflexivity”) suggest it involves “interrogating practice at a deeper level” (p. 217) including the analysis of practice for its assumptions, questioning the interests being served and the knowledge drawn on, and examining how practices shape knowledge as well as the discipline. This necessarily involves the “consideration of the power, politics and ethics underlying practice” (p. 217). Guiding questions for this ideal-type could include the following: (a) What values, beliefs, and assumptions underlie my/our action, and more generally, the work done in the field of HP in this setting/context? (b) What power structures might this kind of practice/action be creating, supporting, or modifying? (c) What forms of knowledge does this practice/action draw on and give validity to, and inversely, what forms of knowledge might it be invalidating or marginalizing? This kind of questioning may also help health promoters analyze possible consequences, both positive and negative, of disrupting the current course of HP practice.

Does the typology resonate with health promoters?

We sought to find out if the typology developed resonates with health promoters. In 2016, the authors identified and invited three health promoters (NB, MHR, and MW) who had experience using reflexivity in their work to contribute examples from their research/practice. We asked them to use a narrative style to briefly describe a specific experience in which they engaged with reflexivity in the context of their work (we call these vignettes). To facilitate the process, we provided them with the typology and a question-based template relating to the use of reflexivity in HP (see Supplemental Appendix 1 available online). Our goal was to see if the typology was relevant and useful for organizing and discussing health promoters’ experiences of reflexivity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Vignettes of Experiences With Reflexivity From Three Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers

| 1 (NB) | Before doing a master’s degree in community

health, I worked as a nurse in a local health

organization. Even though the organization’s

mandate included health promotion, it was

particularly difficult for professionals to

integrate health promotion into their practice,

given that the daily schedule was overloaded with

individual appointments. Reflecting back on this

situation, I realized that we were working in an

environment where the organizational culture was

mostly focused on providing clinical care, and

that the supply of health services were more

reactive, defined by demand, without necessarily

anticipating the population’s needs. I also

realized that professionals had little

understanding of the importance of acting on the

social determinants of health. After becoming a professional in a regional public health department, I continued to reflect on the conditions that would support the integration of health promotion into the practices of my former colleagues in local health organizations. The triggering event that allowed me to think about a concrete solution for this problem was a meeting with the executive director of a community primary care center, who wondered whether there was a real possibility to support health promotion practice in his organization. I realized then that challenges for integrating health promotion into the health system were more organizational, requiring the implementation of a different structure of training that would, apart from enhancing the health professionals’ competencies, also modify organizational conditions of practice. I started reading about practice change processes, professional development, adult education/learning, and reflexivity. Through my reading, it became clear to me that to achieve this shift in practice, we would need to create a space for collective reflection allowing professionals to question their practices and their organizational environment, to better understand health promotion and how to implement health promotion practice. Prompted by this, I developed a professional development program, the Health Promotion Laboratory, targeting public health professionals from local health and social services centers. This professional development project aims to support multidisciplinary teams of local centers in planning new health promotion interventions, building on a collaborative learning, participatory and reflective approach. Throughout the Health Promotion Laboratory processes, teams are encouraged to revisit their individual and preventive care practices from a health promotion perspective and a social determinants of health angle. For instance, a team from the education sector, whose members have long focused on the individual management of school dropout, has now collectively developed (with community partners) an intervention to foster student retention at school. |

| 2 (MHR) | As part of my PhD research I conducted ethnographic fieldwork with health promoters in the City of Copenhagen (see, e.g., Rod, 2015). Among other things, I followed the implementation of a program that sought to involve parents of teenagers in preventing (or at least postponing) the onset of alcohol use. One of the aims of the fieldwork was to tease out the moral and ethical dimensions of alcohol prevention and, at several occasions, I engaged in discussions with health promoters in order to stimulate reflexivity about these issues. During these discussions I presented a framework for reflexivity concerning the ideas and assumptions underlying professional practices. The basic idea was that specific health promotion policies and interventions are bound to answer the question “How should one live?” in particular ways that are rarely made transparent and explicit. Inspired by Lakoff and Collier (2004), I asked health promoters to consider three dimensions of this question: (i) The “how”: i.e. reflexivity concerning the specific techniques that are used to promote health and induce change in people’s lives. (ii) The “should”: i.e. teasing out implicit norms and values. And (iii) The “one”: i.e. addressing the implicit assumptions about the target group. The discussions showed that the health promoters did not always agree about basic underlying ideas and premises of their work. Thus, the value of the framework (and perhaps of reflexivity more generally) was not to enable consistent interpretations and clear conclusions, but rather to highlight inherent ambiguities in health promotion practice. E.g., the alcohol prevention program promoted the idea that parents should adopt a restrictive stance towards the alcohol use of all children below the age of 16 and should refrain from entering into negotiations on this issue. In contrast, some health promoters had adopted a more open and flexible stance towards the alcohol use of their own children, because they felt that it was more important to nurture trust and to take stock of the individual child’s maturity level. At a more general level, this example highlights a potential contradiction between the generalized advice and knowledge claims that are made in health promotion programs and the situated nature of personal relations with which such programs interfere. |

| 3 (MW) | A team of researchers developed an approach to

promote reflexive practice in health promotion and

prevention in Germany called Participatory Quality

Development (PQD) [PQD Handbook http://www.pq-hiv.de/en]. At the core

of PQD is the critical reflection on the power

dynamics in developing and implementing

interventions, specifically advocating for the

participation of community members and

non-professional actors. We conduct various

activities, such as workshops, to promote a

culture of reflexivity among communities of

practice. In one workshop, a social worker described a drop-in neighborhood center for mothers with young children located in a poorer district in a large German city. The center’s purpose was to strengthen the bond between new mothers and their children, and thus prevent later involvement of child protection or family services. This included addressing several well-being and health related topics. Very few mothers were using the center, so the staff began to reflect on why. They decided to work with a university to conduct a qualitative study of the mothers to understand their needs. The study revealed several issues, particularly the need to be relieved periodically of childcare responsibilities. The social worker described how she and her colleagues struggled with this issue, as their mandate from the local authority was to promote the mother-child bonding. In the workshop, we critically examined the assumptions behind the center, particularly the focus on bonding, implying that the mothers were deficient in this area. A service was proposed without first finding out what the mothers needed; they were objects of an intervention and not partners in promoting health. The problem and the solution were formulated based on expert knowledge, excluding lived experience. During the discussion, the social worker became irritated, saying that her organization was not certified to provide childcare, and that they would need more staff and possibly different facilities. She then suggested that they could potentially justify the additional service if, during childcare, the mothers would agree to participate in childrearing training. The other workshop participants—who were predominantly women, many of whom also mothers—questioned the reasoning of the social worker. They argued that the need to be relieved of childcare responsibilities is common among mothers. Whereas, middle class mothers can use well-resourced networks of other parents; mothers in poorer neighborhoods tend to be in networks whose members are overburdened with their own lives. Also, middle class mothers are not seen categorically as having deficits, unlike the mothers in the district under question. Instead of working with the mothers to problem-solve about childcare issues to give them more free time, the social worker assumed that she needed to provide another service, reinforcing the client role of the mothers. The reflexive dialogue at the workshop resulted in the participants becoming aware of how the logic of service provision can objectify “target groups,” preventing them from being seen as competent partners and real-life experts in the development of services. |

The three vignettes (see Table 3) offer different illustrations of how the conceptual categories (i.e., ideal-types) of the typology can be used to interpret and describe the experiences of reflexivity.

Table 3.

Illustrations of Ideal-Types in the Vignettes

| Vignettes | Ideals-Types Identified in Each Vignette |

|---|---|

| Vignette 1 (NB) |

Reflexivity on

action The professional used reflexivity to investigate how the general orientation of the services provided by her organization prevented her from accomplishing her full mandate. She later built on her learning and experience to identify and develop a concrete solution to deal with this problem. Reflexivity underlying action The professional also used reflexivity to question the structures and the practice conditions of the current system, resulting in a proposition to modify them. |

| Vignette 2 (MHR) |

Reflexivity underlying

action Reflexivity was mainly used by this researcher to critically question the premise of alcohol prevention practices in the context of a specific health promotion program, “teasing out the moral and ethical dimensions of alcohol prevention” more broadly. By questioning the political and cultural values/assumptions that “underlie” this health promotion program, the researcher highlighted inherent ambiguities within health promotion knowledge and practices, and its contradictions with the situated experiences of those for whom the programs are created. |

| Vignette 3 (MW) |

Reflexivity in action In a workshop with practitioners and a researcher, engaging reflexivity allowed participants to recognize that a maternal drop-in center located in a low-income neighborhood was not reaching its target population (mothers). Reflexivity on action Reflexivity was used to explore the relevance and the rationale of the service provided, with respect to the center’s mission (improving mother–child bonding early to reduce subsequent recourse to child protection and family services). Reflexivity underlying action Reflexivity also allowed actors to challenge the assumption that the mothers were inadequately bonding with their children. It uncovered how service provision logic can objectify target groups, as well as some contradictory assumptions about mothers’ needs and the center’s vision. |

In the first vignette (NB), the professional realized that her daily workload, as well as the general orientation of the services provided by her organization, prevented her from accomplishing her full mandate. She reflected on her work situation, which differed both from her expectations and from policy requirements, in order to identify what prevented her from carrying out all the functions attached to her position. We identified this as reflexivity on action. She did not question or critique the mandate and purpose of her job (which would have been reflexivity underlying action), rather, she tried to understand why she could not act as expected by her professional system. Taking on an administrative position later in her career, and still juggling with the paradox of not being able to carry out the functions related to her position, she used the knowledge she gained from her previous experiences to identify and develop a concrete solution for this problem (again, reflexivity on action). Throughout this process, she was drawn to investigate the fundamental reasons why integrating HP into the health system was difficult, and concluded that the reasons were structural and that the problem had to be formulated differently. She questioned the structures and the practice conditions of the current system, resulting in a proposition to modify these by creating a collective space for health professionals to reflect on and improve their practices, and experiment with new ones (reflexivity underlying action).

The second vignette (MHR) centrally illustrates the ideal-type of reflexivity underlying action, given that the main aim of this researcher’s project was to critically question the premise of alcohol prevention, and the implementation of an HP program on which he was conducting his ethnographic research. He describes the aim of his work as “teasing out the moral and ethical dimensions of alcohol prevention.” Identifying, or exposing, the moral and ethical dimensions of a HP program involves precisely the questioning of the political and cultural values or assumptions that “underlie” HP work, the kind of questioning that defines for us reflexivity underlying action. This reflexivity underlying action, engaged in this case by the researcher himself, is part of larger systemic change creating awareness about the field of action at large and encouraging alternative perspectives. As the author of this vignette highlights, the goal of his work was not to streamline thinking or enable consistent interpretations or conclusions about the action, but rather to highlight inherent ambiguities in HP practice and its contradictions with the situated experiences of those for whom these programs are created. The author of this vignette also challenged health promoters working within the alcohol prevention program. He introduced his critique into the project through discussions with health promoters with an intention to stimulate, or at least encourage, their own processes of reflexivity on action and reflexivity underlying action, and as such, the project interweaves both ideal-types in its reflexive process.

The third vignette (MW) presents an account of reflexivity from the perspective of a researcher using Participatory Quality Development workshops to promote reflexive practice in HP. During one workshop, a social worker voiced concern that few mothers were coming to the drop-in center located in a low-income neighborhood, whose mission was to strengthen the bond between mothers and their children. This reflexivity in action within her team led to the development of a qualitative research project on mothers’ needs. The study found that mothers needed occasional time off from child care (rather than child-rearing training), but the social worker found that this need was contrary to the center’s mission. Thus, reflexivity on action was engaged through group discussions (i.e., questioning the center’s mission of improving mother–child bonding to reduce subsequent recourse to child protection and family services) and was further deepened through reflexivity underlying action at a broader level of questioning social inequalities for mothers (i.e., challenging the assumption that some mothers were inadequate in bonding with their children). In this vignette, the discussions between the social worker and other workshop participants regarding the mission of the center and the needs of the mothers displays the dynamic fluidity between all three types of reflexivity, thus demonstrating the complex interactions between them. The practitioners were confronted with their assumptions as professionals about the logic of service provision and their assumptions as middle-class women about motherhood, child care, stress, and time management. The reflexive dialogue during the workshop resulted in the participants becoming aware of how the logic of service provision can objectify “target groups,” disenfranchising the mothers from being partners in developing services that would value their knowledge, experience, and needs.

Discussion

The typology can be used to organize, describe, and discuss HP actors’ experiences with reflexivity, which may be particularly useful for HP training. Instilling continuous learning and development of skills, such as reflexivity, in training is viewed as crucial to prepare responsible health professionals (Mann et al., 2009). The vignettes highlighted two important ways in which the typology can be used in training, and these are discussed below.

First, the vignettes illustrate that the three ideal-types are relevant descriptors of a continuum of positions HP actors can take in relation to what they do and how they can learn from these different positions. Reflexivity in action describes an immediacy of reflection, signaling feedback to instantly readjust a problematic professional situation during an action. This kind of reflexivity allows for solving problems at hand, without questioning the causes of the problem, how it has been conceived or its implications. Reflexivity on action describes the HP actor’s engagement with more complex questions about the problem and its solution once the action is completed. This allows actors to develop new models of action from a complex, unexpected situation of practice and to integrate this learning into future action. In these cases, improvement is considered in relationship to already formulated goals and problem. For instance, we see reflexivity on action in the first vignette, wherein the HP professional confronted a problematic situation by first identifying its cause, by then exploring potential avenues of action and by framing an initial solution that fit within the limits of her professional system. As such, this kind of reflexivity focuses post hoc on the use of action strategies, but without necessarily challenging the aim of the action or its underlying premises. In contrast, engaging in reflexivity underlying action allows HP researchers and practitioners to question the wider HP assumptions about health, the premises on which the problem has been defined, as well as the moral and ethical implications of HP actions and practice. For instance, we see reflexivity underlying action mostly in the second and third vignettes, with examples of researchers and practitioners questioning the emphasis on individual choices, the norms and values promoted by HP interventions, or the implicit beliefs of HP actors. Reflexivity underlying action should necessarily take into consideration the perspectives of various population as well as the assumptions that health promoters themselves make as part of their programs in order to critically address the power imbalance and potential bias underlying the promotion and definition of health and healthy behaviors of others that is absent of contextualization. Although the relevance of engaging in various forms of reflexivity is a priori acknowledged within HP, engaging in reflexive critique of the field is rare. As Tretheway et al. (2015) argue, while HP practitioners “consider critical values and principles to be intrinsic to their work, they are often not made explicit or realized in practice” (p. 216). However, fostering this kind of critical stance in future generations of HP practitioners is essential for a moral and responsible evolution of the field.

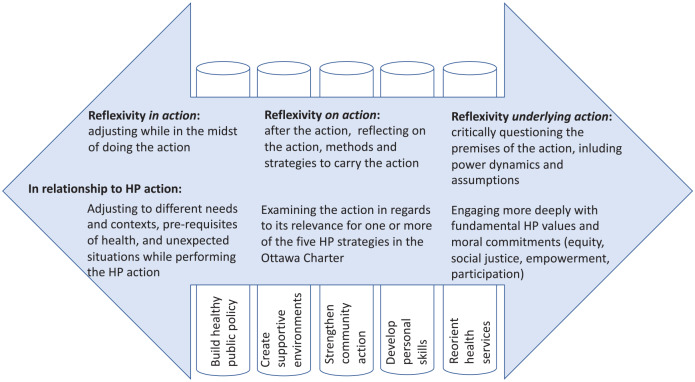

Second, the three ideal-types are relevant abstractions to accommodate contemplation of the numerous kinds of action in which students in HP will eventually engage as practitioners. Positioning an experience within the typology requires the identification and definition of what HP action involves. This is important because action itself is at the core of any HP work. HP initiates, supports, and sustains social change processes and interventions (programs and policies) at various levels with several strategies that have been outlined in the Ottawa Charter (World Health Organization, 1986). The charter emphasizes fundamental principles and values for the field of HP (i.e., equity, social justice, empowerment, participation) as well as five main strategies for HP: (a) building healthy public policy, (b) creating supportive environments, (c) strengthening community actions, (d) developing personal skills, and (e) reorienting health services. Our three ideal-types of reflexivity address different levels of the Ottawa Charter action strategies and may be used to facilitate their integration and application within HP practice. For instance, while reflexivity in action refers to adjustments made in the midst of performing an action (e.g., adapting a health promoter’s discourse to stakeholders’ literacy), reflexivity on action could be related to examining the action in regards to its alignment with/relevance for one of the five strategies of HP action (e.g., fostering the development of stakeholders’ literacy skills). Reflexivity underlying action, for its part, could be likened to engaging with fundamental HP values and moral commitments regarding the action (e.g., questioning the systems and dynamics that have contributed to the stakeholders’ levels of literacy and how HP practice partakes in or counters this). By superimposing our typology on this seminal document for HP, we aim to encourage a coherent and integrated understanding of reflexivity across different kinds of HP action (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Continuum of Reflexivity in Health Promotion (HP)

While reflexivity is recognized as an important learning objective for HP training (Boutilier & Mason, 2017; Caplan, 1993; Eakin et al., 1996; Kickbusch, 2007; Tretheway et al., 2015), guidelines and frameworks as to how to facilitate the understanding and acquisition of this skill in the pedagogical literature for HP are scarce. Reflexivity is a complex concept for students and early career professionals in HP, and the particularities of the concept also complicate the development of reflexive skills in students. For instance, there are a multitude of equivocal concepts of reflexivity coexisting in the health sciences all having different purposes, and making a coherent understanding challenging (Fleming, 2007). Indeed, the breadth of reflexivity’s purpose can be a barrier in training since there is often ambiguity of the educator’s goals with regard to the use of reflexivity (Chaffey et al., 2012). Although learning about reflexivity can be an empowering experience for HP practitioners, its consequences are challenging for them because it can lead to a raised awareness of tensions in their practice and ambivalence toward the organizational structures and institutional rules in which they are bound (Jacobs, 2008).

Acknowledging that reflexivity has been neglected as a key competency in HP training, Wigginton et al. (2019) outline a course they developed concretely linking HP core competencies to different forms of reflexivity—“reflection on” and “reflecting about” practice. Along similar lines of thinking, our typology clarifies three types of reflexivity with different purposes and processes within HP practice, which we believe can be useful for better integrating reflexivity into HP courses. Furthermore, being reflexive involves stepping back from experience, which trainees have little experience with at such an early stage of their career. While our typology does not substitute experience that students will eventually gain, it might help in circumscribing particular level of objects (strategies, values, and principles) of reflexivity within the field.

It is for these reasons that we consider the typology as useful for HP training because it offers three meaningful categories to help trainees understand and integrate reflexivity as a key competency to develop in HP research and practice. We think the typology can be useful to organize discussions about reflexivity in various settings and locations, not prescriptively or as a guide, but as a shared language to reflect on experiences. Specifically, the typology may be useful in graduate and postgraduate public health and HP training that aims to foster reflexive practices among trainees when thinking about their experiences in internships or research projects. Within all HP research and practice, but perhaps particularly when integrating a reflexive stance into one’s work, it is also critical to consider the historical, political, and social contexts of the population being addressed and to understand how their specific perspectives might affect and shape the HP practice itself. This form of stepping back can be encouraged by some of the question prompts integrated into the three ideal-types.

Conclusion

Despite the growing recognition of reflexivity’s significance for HP research and practice, frameworks to support the integration of this concept into training for the field of HP are lacking. We synthesized existing theories and frameworks of reflexivity into a typology for HP, acknowledging HP as “a field of action” within public health (McQueen, 2001), in which various kinds of actors (researchers, professionals, policymakers, citizens, and communities) engage with complementary and contested values in, on, and underlying their work at many levels and in different contexts (Potvin & Jones, 2011). This organizing framework has the potential to be a useful tool for training in HP that brings an overarching structure under which the multiple existing theories, models, and classifications of reflexivity from other fields and disciplines can be included in a synergistic way for HP students, trainees, and professionals to learn about reflexivity. We envision the typology as a companion to the Ottawa Charter for training in contemporary HP because learning about HP action strategies should be inseparable from learning about reflexivity to question one’s own actions to achieve HP goals within a system (in and on) as well as to question the system itself and the goals of HP (underlying). We think that the typology can be a device to bridge conversations about reflexivity across different training curricula, communities of practice, and traditions in the field of HP.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, HPP912407_suppl_mat for Reflexivity in Health Promotion: A Typology for Training by Stephanie A. Alexander, Catherine M. Jones, Marie-Claude Tremblay, Nicole Beaudet, Morten Hulvej Rod and Michael T. Wright in Health Promotion Practice

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Louise Potvin and Katherine Frohlich for their feedback on an early version of this article in 2017. We would like to thank all the participants of the IUHPE conference workshop on reflexivity in health promotion in Thailand in 2013 for their active participation in small groups where we introduced the first iteration of this work. Finally, we would also like to acknowledge the work of Selma Chipenda Dansokho for her detailed edit of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Stephanie A. Alexander is now at Fondation d’entreprise MGEN pour la santé publique, Paris, France.

M-CT is funded by a Research Scholar award (Junior 1) from the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (no. 268417). SA acknowledges funding from AXA Research France and a SSHRC post-doctoral fellowship.

CMJ was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research from 2013-2016 (no. CGV127503).

ORCID iDs: Stephanie A. Alexander  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0445-0116

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0445-0116

Marie-Claude Tremblay  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4965-2515

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4965-2515

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online at https://journals.sagepub.com/home/hpp/.

References

- Allen-Scott L. K., Hatfield J. M., McIntyre L. (2014). A scoping review of unintended harm associated with public health interventions: Towards a typology and an understanding of underlying factors. International Journal of Public Health, 59(1), 3-14. 10.1007/s00038-013-0526-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisset S., Tremblay M. C., Wright M. T., Poland B., Frohlich K. L. (2017). Can reflexivity be learned? An experience with tobacco control practitioners in Canada. Health Promotion International, 32(1), 167-176. 10.1093/heapro/dav080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam B., Chamberlain K. (2003). Professionalization and reflexivity in critical health psychology practice. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(2), 215-218. 10.1177/1359105303008002661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boud D., Keogh R., Walker D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P., Wacquant L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier M., Mason R. (2017). The reflexive practitioner in health promotion: From reflection to reflexivity. In Rootman I., Pederson A., Frohlich K. L., Dupéré S. (Eds.), Health promotion in Canada. New perspectives on theory, practice, policy, and research (4th ed., pp. 328-342). Canadian Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R. (1993). The importance of social theory for health promotion: From description to reflexivity. Health Promotion International, 8(2), 147-157. 10.1093/heapro/8.2.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffey L. J., de Leeuw E. J., Finnigan G. A. (2012). Facilitating students’ reflective practice in a medical course: Literature review. Education for Health, 25(3), 198-203. 10.4103/1357-6283.109787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin J., Robertson A., Poland B., Coburn D., Edwards R. (1996). Towards a critical social science perspective on health promotion research. Health Promotion International, 11(2), 157-165. 10.1093/heapro/11.2.157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P. (2007). Reflection a neglected art in health promotion. Health Education Research, 22(5), 658-664. 10.1093/her/cyl129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guichard A., Tardieu É., Nour K., Lafontaine G., Ridde V. (2019). Adapting a health equity tool to meet professional needs (Québec, Canada). Health Promotion International, 34(6), e71-e83. 10.1093/heapro/day047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issitt M. (2003). Reflecting on reflective practice for professional education and development in health promotion. Health Education Journal, 62(2), 173-188. 10.1177/001789690306200210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs G. C. (2008). The development of critical being? Reflection and reflexivity in an action learning programme for health promotion practitioners in the Netherlands. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 5(3), 221-235. 10.1080/14767330802461306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., MacDougall C. (2007). Reflective practice. In Keleher H., NacDougall C., Murphy B. (Eds.), Understanding health promotion (pp. 244-251). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. (2007). Health governance: The health society. In McQueen D. V., Kickbusch I., Potvin L., Pelikan J. M., Balbo L., Abel T. (Eds.), Health and modernity. The role of theory in health promotion (pp. 144-161). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S., Kinder P. (2002). Reflexive practice: The relationship between social research and health promotion in HIV prevention. Sex Education, 2(2), 91-104. 10.1080/14681810220144855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R. (1994). Health promotion and empowerment: Reflections on professional practice. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 253-268. 10.1177/109019819402100209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R., Mohindra K., Schrecker T. (2011). The growing impact of globalization for health and public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 263-283. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff A., Collier S. J. (2004). Ethics and the anthropology of modern reason. Anthropological Theory, 4(4), 419-434. [Google Scholar]

- Mann K., Gordon J., MacLeod A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 595-621. 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda J., Zupancic T., Crighton E., Muhajarine N., Phipps E. (2014). Equity-focused knowledge translation: A framework for “reasonable action” on health inequities. 59(3), 457-464. 10.1007/s00038-013-0520-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen D. V. (2001). Strengthening the evidence base for health promotion. Health Promotion International, 16(3), 261-268. 10.1093/heapro/16.3.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin L., Jones C. M. (2011). Twenty-five years after the Ottawa Charter: The critical role of health promotion for public health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 102, 244-248. 10.1007/BF03404041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin L., McQueen D. V. (2007). Modernity, public health, and health promotion. In McQueen D. V., Kickbusch I., Potvin L., Pelikan J. M., Balbo L., Abel T. (Eds.), Health and modernity. The role of theory in health promotion (pp. 12-20). Springer; 10.1007/978-0-387-37759-9_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schön D. A. (1991). The reflective practitioner: How health professionals think in action. Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Shareck M., Frohlich K. L., Poland B. (2013). Reducing social inequities in health through settings-related interventions: A conceptual framework. Global Health Promotion, 20(2), 39-52. 10.1177/1757975913486686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teekman B. (2000). Exploring reflective thinking in nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(5), 1125-1135. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay M.-C., Richard L., Brousselle A., Beaudet N. (2014). Learning reflexively from a health promotion professional development program in Canada. Health Promotion International, 29(3), 538-548. 10.1093/heapro/dat062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretheway R., Taylor J., O’Hara L., Percival N. (2015). A missing ethical competency? A review of critical reflection in health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 26(3), 216-221. 10.1071/HE15047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton B., Fjeldsoe B., Mutch A., Lawler S. (2019). Creating reflexive health promotion practitioners: Our process of integrating reflexivity in the development of a health promotion course. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 5(1), 75-78. 10.1177/2373379918766379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1986, November 21). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Switzerland: First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, Canada http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, HPP912407_suppl_mat for Reflexivity in Health Promotion: A Typology for Training by Stephanie A. Alexander, Catherine M. Jones, Marie-Claude Tremblay, Nicole Beaudet, Morten Hulvej Rod and Michael T. Wright in Health Promotion Practice