INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a global health emergency creating unprecedented social, political, and economic crises. First noted in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has infected more than 5.1 million people in 216 countries as of May 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). It was formally declared a pandemic in March 2020 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Unlike other coronavirus strains, this highly contagious disease has resulted in significant morbidity and mortality with severity ranging from asymptomatic carriers to critical illness, rapid decompensation, and death. Health care infrastructure was faced with extraordinary challenges to provide care for the mass influx of infected patients. This response revealed scarcities of critical resources required to treat these patients while ensuring staff safety.

Background

The state of Michigan documented its first case of COVID-19 on March 10, with the number of cases quickly escalating to over 16,000 in the next 3 weeks, creating a state of emergency and prompting a stay-at-home order on March 23 (Whitmer, 2020b). Four Detroit-area counties, namely, Washtenaw, Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb comprised approximately 71% of Michigan's COVID-19 cases as of early May (State of Michigan, 2020). Detroit-area hospitals were tasked with mobilizing institutional resources, including personnel, personal protective equipment (PPE), and the necessary medical supplies required to provide care for the surge of COVID-19 patients.

A large academic medical center, located approximately 70 kilometers outside of Detroit, postponed elective surgeries, shifted outpatient clinics to telemedicine visits, and limited outside hospital transfers to only COVID-19 positive patients. On March 24, this academic medical center opened a dedicated COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) as phase one of the pandemic response. Ultimately, ICU bed capacity increased by 74 adult beds for a total of 181 ICU beds.

Expanding ICU bed capacity identified a need for additional care providers. This strain was felt across the state, resulting in Executive Order 2020–30, which suspended restrictions in the scope of practice, supervision, and delegation to nurse practitioners (NPs) professionally employed and responding to increase their facility's response to the pandemic (Whitmer, 2020a). The order permitted NPs “to provide medical services appropriate to the professional's education, training, and experience, without physician supervision and without criminal, civil, or administrative penalty related to a lack of such supervision” (Whitmer, 2020a, para. 9). To meet the challenge of the frontline provider deficit, pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs), with experience in the management of acute and critically ill patients, were a valuable resource to the COVID-19 ICU. As a result, emergency credentialing privileges were granted to a group of PNPs who were then deployed to the COVID-19 ICU as frontline providers. This group of PNPs, equipped with evolving global and institutional COVID-19 standards of care and adult critical care guidelines, combined with support from adult critical care medicine faculty, provided frontline care to critically ill COVID-19 patients.

SUMMARY OF PROVIDER DEPLOYMENT TO THE COVID-19 ICU

An initial call for volunteers to staff the COVID-19 ICU was sent to inpatient advanced practice providers (APPs), including NPs, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and physician assistants. With surgeries postponed and the stay-at-home order in effect, many areas of the hospital experienced low patient census, thus allowing for APPs to redeploy to the COVID-19 ICU. Once deployed, most of the APPs committed to a period in the COVID-19 ICU, only returning to their home unit once they fulfilled this commitment or if their home unit required their return for other patient care needs. Following deployment, an email survey was sent to all APPs who worked in the COVID-19 ICU regarding their background, education, usual scope of practice, and overall experience during deployment.

The survey results depicted varied backgrounds and levels of experience of the APPs who worked in the COVID-19 ICU. Of those deployed, 28.5% were PNPs from pediatric critical care, and 11.9% were PNPs from pediatric acute care. Certified registered nurse anesthetists accounted for 40.5% of the APPs; 2.4% were adult NPs, deployed from adult critical care. The remaining 16.7% were a mix of physician assistants and NPs, originally based in adult acute care units. Of all APPs, 35.7% had been in practice for over 8 years. Over half, 66.7% of APPs reported responsibilities in the COVID-19 ICU were beyond their typical scope of practice. Of the PNPs, 80% routinely managed ventilators and vasoactive medications before deployment.

Educational resources were shared via cloud computing and were frequently updated as information evolved. This information included literature pertaining to COVID-19 treatment, PPE, unit workflow, and COVID-19 ICU orientation guidelines. Given the diverse backgrounds of the APPs, standardized protocols were put in place to guide nearly all facets of patient care. Protocol topics included sedation, ventilator management strategies, resuscitation and hemodynamic support, nutrition plans, tracheostomy guidelines, and venous thromboembolism management. PNPs were provided 4 hr of orientation to the COVID-19 ICU. Upon survey, 80% of PNPs described their perception of preparedness ranging from neutral to definitely prepared.

COVID-19 ICU PATIENT POPULATION

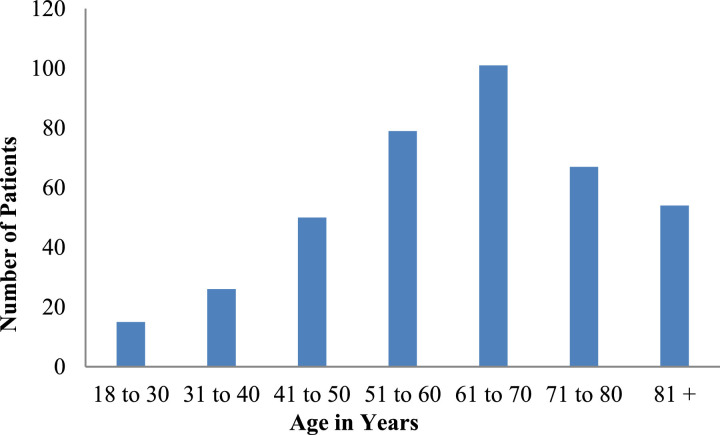

Data were collected from the University of Michigan Health System's Data Direct Bank from March 1, 2020, to May 1, 2020. During this time, there were 392 COVID-19 positive patients admitted; Figure 1 graphs the age distribution of all admitted patients. Of the admitted patients, 218 were ICU status, 82 of whom were female, and 136 were male, with an average age of 60.1 years and 59.8 years, respectively. The most common comorbidities were hypertension, disorders of electrolyte and fluid balance, diabetes, obesity, cardiac arrhythmia, renal failure, chronic pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure.

FIGURE 1.

Age distribution of COVID-19 patients.

(This figure appears in color online at www.jpedhc.org.)

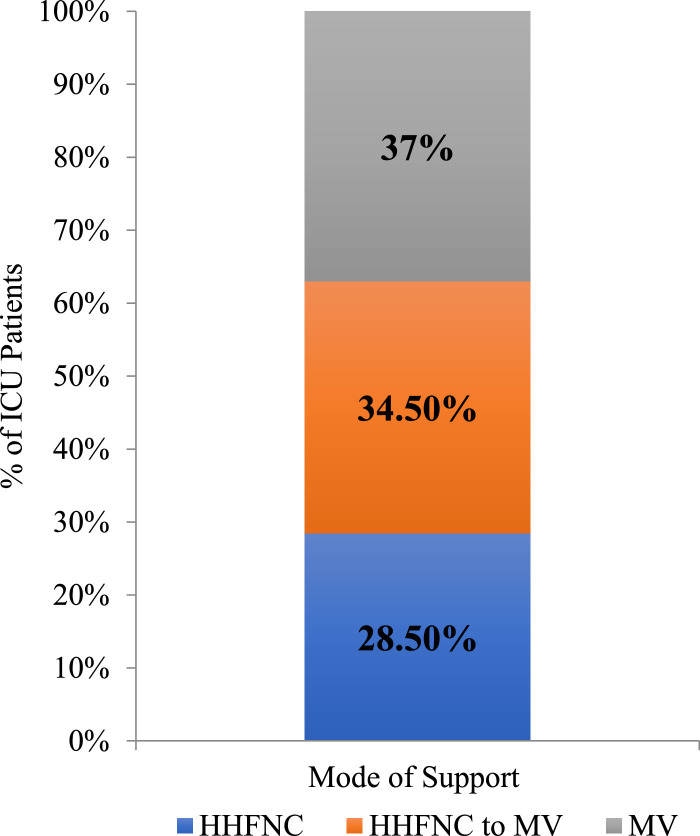

All ICU patients required respiratory support; Figure 2 demonstrates the mode of respiratory support used: high flow nasal cannula, high flow nasal cannula with escalation to mechanical ventilation, or mechanical ventilation. The average ventilator days for patients discharged as “alive” was 8.8 days, for patients discharged as “deceased” or “to hospice” was 10.4 days, and for those discharged as “undetermined” was 19.6 days. Undetermined accounts for patients who fall outside the dates of data collection. Continuous renal replacement therapy was required in 19% of ICU patients and 5% of patients qualified for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, based on institutional criteria specific to COVID-19.

FIGURE 2.

Respiratory support required during COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) admission. HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; MV, mechanical ventilation.

(This figure appears in color online at www.jpedhc.org.)

TEAM STRUCTURE AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The COVID-19 ICU care teams were multidisciplinary and consisted of members from a variety of backgrounds and experiences. Standardized roles and responsibilities were developed to support staff in an environment of rapidly changing work processes and standards of care, with special attention to staff safety.

Acknowledging potential staffing shortages, provider teams were organized using a hybrid of a tiered staffing strategy adapted by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. In this model, the shortage of adult intensivists requires the support of other physicians and APPs to meet patient care needs (Halpern & Tan, 2020). Most notably, APPs who have both critical care training and experience are utilized to directly augment the critical care physician leading the care team (Halpern & Tan, 2020). The COVID-19 ICU team included an attending physician, a critical care medicine fellow, and two to four APPs. One side of the COVID-19 ICU was staffed by adult critical care medicine faculty, and the other side was staffed by pediatric critical care medicine faculty, with adult critical care medicine faculty readily available for consultation and/or present for daily rounds. In addition, a combination of critical and acute care nurses, and a respiratory therapist, were assigned to groups of patients. The daily rounding team also included a pharmacist and infectious disease consultant, with other subspecialty consultants available as needed.

APPs were frontline providers, responsible for the care of four to six patients on the day shift and up to 10 patients on the night shift. Shifts were 12 hr long, and APPs were usually scheduled in stretches of days in a row to ensure patient continuity.

The Table describes the specific responsibilities of providers on the care team. One provider, usually the attending or APP, conducted daily patient physical examinations. The most experienced provider available performed the procedures, to promote efficiency and reduce the time and number of providers exposed. Accordingly, anesthesia providers performed intubations.

TABLE.

Provider team responsibilities in COVID-19 ICU

| Provider | Provider Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Attending | Primary decision maker; primary contact for frontline providers and fellow; review and approve admissions; daily physical examination;a sign notes and bill procedures |

| Fellow | Bed management; assist with admissions and decompensating patients; procedures including lines, point-of-care ultrasounds; attend twice daily safety rounds; general awareness of unit acuity |

| Frontline provider (APP) | Knowledge of medical details; presentation on rounds; formulate daily plan of care; evaluate and adjust plan of care as needed; place orders; write admission and daily progress notes; communication with patients’ families; first contact for nurse and respiratory therapist; procedures including lines, point-of-care ultrasounds |

Note. APP, advanced practice providers.

Discussed and routinely performed by one provider.

LESSONS LEARNED

As pediatric providers deployed to a COVID-19 ICU, lessons learned extend beyond the pathophysiology and pharmacology unique to the adult and geriatric population. PNPs adapted to a new unit, learned to identify variations in nursing background among new colleagues, and practiced with an extended scope of practice. These were not without challenges, including workflow, communication, and emotional burdens unique to pandemic medicine.

The daily realities of the COVID-19 ICU were outside of every provider's typical prepandemic workflow. In preparation for work in the COVID-19 ICU, a 4-hr orientation to the unit and patient population was provided. The remainder of education was a self-driven review of evolving guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19. The brevity of this orientation provoked fear and anxiety; however, education and clinical experience as NPs provided the skills to adapt to this unforeseen change in practice.

In typical practice, colleagues are familiar and have established rapport; as such, team members can adapt to complement the expertise of individuals. Upon deployment to the COVID-19 ICU, not only were PNPs faced with a new environment and patient population, each day they joined a new team with different members. Each team member's strengths and weaknesses were unknown. This was a systematic flaw based on circumstances beyond individual control.

An unexpected but pleasant outcome of working with a group of unfamiliar colleagues was the convivial spirit. In a situation plagued with unknowns, there was an abundance of well-intentioned people doing their best to provide the most comprehensive care in their power. Common themes throughout the COVID-19 ICU were kindness, support, and understanding, all while working together to meet the needs of critically ill patients.

The team's focus expanded beyond individual patient care to include overall global health. Efforts to limit provider exposure and preserve PPE altered the flow of patient care and required unconventional communication methods when face-to-face communication was not possible. This approach often required PNPs to be outside of patient rooms, peering through windows to communicate with the team inside via phone or walkie-talkie. In an effort to limit exposure of all team members, PNPs coordinated with bedside staff and adjusted the plans of care based on timing of room re-entry. Likewise, the timing of laboratory collections, ventilator changes, and patient repositioning was more fluid than usual; at times, the PNPs performed these tasks themselves.

Interactions with patients’ families were also disrupted; visitation by family and friends of patients was not permitted to minimize exposure of both visitors and staff. Patients’ families were updated regularly via phone; without in-person interactions, there was a loss of intimacy, especially when sharing bad news. This approach proved challenging, as it is difficult to deliver bad news when families were not present to witness the patient's condition. Media coverage surrounding COVID-19 exacerbated communication barriers with families, as public information was not always accurate and was frequently changing; thus, providers spent a lot of time educating patients’ families and debunking misinformation.

The emotional hardship endured throughout this pandemic was one of the most challenging aspects, affecting every clinician. Most of the PNPs felt their work in the COVID-19 ICU was both more stressful and emotionally challenging than their typical work. While caring deeply for the patients, PNPs often felt helpless in the face of their care. All the while, providers were concerned about their own health and risk of contracting COVID-19, as well as spreading the virus to their families. This concern resulted in decontamination practices and even isolation or self-quarantine. Despite the circumstances, the PNPs returned day after day to serve on the frontlines of the pandemic.

At the beginning of the pandemic, 80% of the PNPs voluntarily deployed to work in the COVID-19 ICU, and 20% were assigned on behalf of their home units. Nevertheless, upon completion of deployment, 73.3% of PNPs stated they would “definitely” volunteer for redeployment in the case of a COVID-19 resurgence, and 13.3% stated they “probably” would.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

PNPs were vital to the provision of care during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating their value in future pandemic planning. Their successful deployment to a COVID-19 ICU provided an opportunity to examine processes and resulting outcomes. For future situations requiring rapid deployment of providers, it is recommended that education is streamlined, team roles and responsibilities are well defined, state and institutional support are elicited, and provider health is prioritized.

As previously mentioned, orientation was minimal and often self-directed. To deploy PNPs to an adult ICU, education and preparation are paramount. PNPs should be provided with a concise orientation to workflow processes, rounding practices, and patient care protocols. A repository for resources should be established using an online platform to collect and disperse resources in real-time. Resources should also include adult critical care order sets, lectures, webinars, evidence-based protocols, and medication research trials. PNPs should be held responsible for ongoing re-education to stay informed of practice changes.

The success of a rapid deployment included temporary state expansion of the NP scope of practice and institutional emergency privileges. These processes were necessary to permit PNPs to practice to their full scope and ability in the provision of care to an overwhelming number of COVID-19 ICU patients. Therefore, in future pandemic planning, we recommend early state-level expansion of the scope of practice and for institutions to establish a process for rapid credentialing to support the expanded scope of practice.

Finally, there is a monumental toll on mental health during a pandemic, making it essential that self-care not only be practiced but also prioritized. Health care providers are vulnerable to psychological distress related to patient care, and quarantine or isolation required because of this work (Torales, O'Higgins, Castaldelli-Maia, & Ventriglio, 2020; Wu, Styra, & Gold, 2020). An institutional mechanism to provide mental health support to staff needs to be available and shared broadly; staff health is essential to ensure ongoing patient care needs are met (Wu et al., 2020). Palliative care and social work teams should be utilized to assist PNPs with the management of patient and family grief and clarifying goals of care, thus helping to off-load this emotionally draining work. Furthermore, when possible, staffing models should cluster days of service to allow for stretches of days off to allow for providers’ emotional and physical recovery.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed healthcare infrastructure, revealing imperfections in the medical system and scarcities of all resources necessary for the delivery of patient care. Providers were an identified scarce resource, leaving open opportunities for PNPs to rise to the challenge and fill this void. Practicing on the front lines required flexibility; it was emotionally draining and difficult work. Despite the adversities, PNPs were resilient and vital to the successful institutional pandemic response, thus reinforcing their role in future pandemic planning.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Michigan Medicine PNPs who deployed to the COVID-19 ICU during the pandemic, including Louise Callow, Courtney Cherniak, Tara Egnor, Chelsea Honstain, Kimberly Kellogg, Laura Meeker, Max Pizzo, Blythe Pollack, Christine Renke, Janella Reske, Stephanie Robell, Kayleigh Schwartz, Stacey Sears, Kimberly Siebert, Natalie Sinicropi, and Rebecca Tompkins. We also recognize the other APPs and critical members of the multidisciplinary team who worked alongside us. We are grateful for the support of the pediatric and adult critical care faculty who provided education and guidance throughout our experience. Thank you to Dr. Christopher Fung, who assisted with patient data collection. Finally, we thank Andrea Kline-Tilford, who encouraged us to document this experience so other PNPs may learn from it.

Biographies

Christine Renke, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Louise Callow, Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Nurse Practitioner, Congenital Heart Center, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Tara Egnor, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Chelsea Honstain, Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, Stem Cell Transplant, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Kimberly Kellogg, Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Nurse Practitioner, Congenital Heart Center, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Blythe Pollack, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Janella Reske, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Stephanie Robell, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Natalie Sinicropi, Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Nurse Practitioner, Congenital Heart Center, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html#covid19-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern N.A., Tan K.S. 2020. United States resource availability for COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.sccm.org/Disaster/COVID19. [Google Scholar]

- State of Michigan . 2020. Coronavirus Michigan data. Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/coronavirus/0,9753,7-406-98163_98173–,00.html. [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66:317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer G. 2020. Executive order 2020-30 (COVID-19) Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90705-523481–,00.html. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer G. 2020. Executive order 2020-42 (COVID-19) Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90705-525182–,00.html. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.E., Styra R., Gold W.L. Mitigating the psychological effects of COVID-19 on health care workers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192:E459–E460. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]