Abstract

Objective

To evaluate urology applicants’ opinions about the interview process during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and Methods

An anonymous survey was emailed to applicants to our institution from the 2019 and 2020 urology matches prior to issuance of professional organization guidelines. The survey inquired about attitudes toward the residency interview process in the era of COVID-19 and which interview elements could be replicated virtually. Descriptive statistics were utilized.

Results

Eighty percent of urology applicants from the 2019 and 2020 matches received our survey. One hundred fifty-six people (24% of recipients) responded. Thirty-four percent preferred virtual interviews, while 41% in-person interviews at each program, and 25% regional/centralized interviews. Sixty-four percent said that interactions with residents (pre/postinterview social and informal time) were the most important interview day component and 81% said it could not be replicated virtually. Conversely, 81% believed faculty interviews could be replicated virtually. Eighty-seven percent believed that city visits could not be accomplished virtually. A plurality felt that away rotations and second-looks should be allowed (both 45%).

Comment

Applicants feel that faculty interviews can be replicated virtually, while resident interactions cannot. Steps such as a low-stakes second looks after programs submit rank lists (potentially extending this window) and small virtual encounters with residents could ease applicant concerns.

Conclusion

Applicants have concerns about changes to the match processes. Programs can adopt virtual best practices to address these issues.

The application process for the 2021 urology residency match will occur during the novel-coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.1 To slow the spread of the virus, governments and medical centers have restricted nonessential travel and gatherings.1 However, the residency application process has traditionally involved significant travel and gatherings, from visiting subinternships to interviews to social events.2

Subinternships have great educational value and allow applicants to much more closely assess individual programs and display their knowledge, work ethic, and personality. Subinternships also allow applicants to obtain letters of recommendation, which are often considered the single most important variable in an application.4 The information obtained from subinternships has a major impact on the rank lists of applicants and residency programs.4 , 5

In the 2020 urology residency match, the average student applied to 74 programs and interviewed at 13 different programs.6 Most residency interviews include a pre or postinterview social event and a full day of tours, informational talks, lunches, and casual down time with the current residents. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to extend into interview season and have a major impact on applicants’ ability and willingness to travel and socialize at residency programs across the country.

In light of the ongoing pandemic, the electronic residency application service will delay the release of applications from the standard mid-September date to October 21, 2020.7 Additionally, the coalition of physician accountability has recommended that programs limit away rotations and in-person interviews as much as possible.8 The Association of Amrican Medical Colleges (AAMC) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) issued a joint statement on May 14, which “strongly encourages” programs to conduct virtual interviews.3 , 9 The Society of Academic Urologists (SAU) now also strongly discourages away rotations and in-person interviews and has delayed the match until early February.10 Unfortunately, many of the executive decisions and recommendations are being made with limited input from the key stakeholders: the applicants. We present our findings from a survey of the applicants to the 2019 and 2020 American Urological Association (AUA) Residency Matches on their experiences and how they would organize the application process in the COVID-19 era. Of note, this survey was conducted prior to the SAU issuing its guidance on the interview season.

METHODS

On May 4, 2020, we emailed an anonymous, de-identified, 30-question, multiple-choice survey to all 666 applicants to our institution for the 2019 and 2020 urology residency matches (80% of applicants nationally). We sent reminder emails to applicants who had not yet completed the survey on May 11 and May 16, and we closed the survey on May 18. The email included a brief description of the study and a link to the survey (RedCap electronic questionnaire), and recipients were informed that participation was optional and anonymous. The survey (Appendix 1) inquired about their experiences with residency applications and their current attitudes towards the match process in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Descriptive statistical analyses were done with R software. The University of Texas Southwestern Institutional Review Board deemed this survey study exempt from review.

RESULTS

Of 666 applicants to urology from the 2019 and 2020 urology matches, 653 received our survey (80% of total applicants). Of the 653 survey recipients, 156 (24%) completed the survey (Table 1 for baseline characteristics). The majority of respondents (85, 54%) will be starting their urology internships in 2020, while 50 (32%) started their urology internships in 2019, and 17 (11%) are reapplying for the 2021 Match.

Table 1.

Survey participants demographics

| Total Applicants in 2019 and 2020 Urology match | 830 |

| Total applicants to our institution | 666 |

| Total applicants receiving survey email | 653 |

| Total complete surveys | 156 |

| Age (average ±SD) | 28 (±2.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 96 (64%) |

| Female | 51 (34%) |

| Other | 1 (0.7%) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (1.3%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 101 (65%) |

| Asian | 23 (15%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 18 (12%) |

| African-American/Black | 6 (4%) |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.6%) |

| Other | 8 (5%) |

| Prefer not to say | 6 (4%) |

| Plans for 2020 | |

| Starting urology residency | 85 (55%) |

| Reapplying to urology residency | 17 (11%) |

| Current urology resident | 50 (32%) |

| Other | 4 (2.6%) |

| Number who did a second look | 9 (5.8%) |

Away Rotations

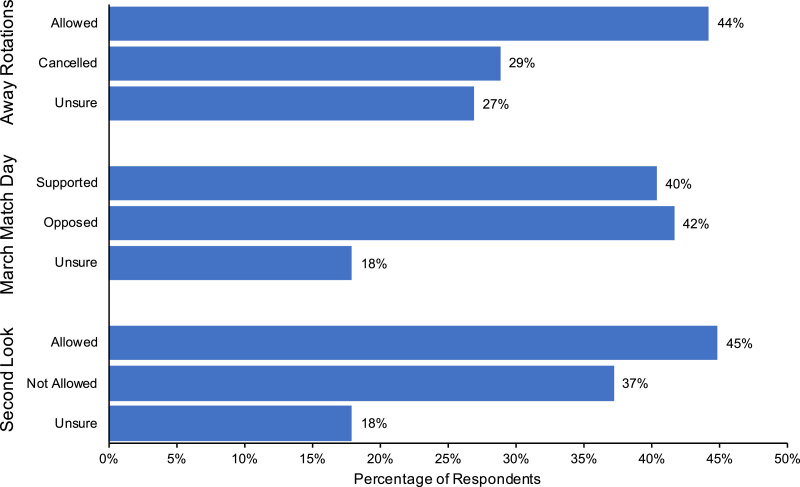

When asked about away rotations, 45 (29%) responded that they should be cancelled, while 69 (44%) said they should be allowed, and 42 (27%) were unsure.

Interview Day

When asked about interviews, only 53 (34%) preferred virtual interviews, while 64 (41%) preferred traditional in-person interviews at each program, and 39 (25%) supported regional or centralized interviews. Most respondents (100, 64%) reported that interactions with residents were the most important component of their interview day; alternative responses included faculty interviews (38, 25%), visiting the site location (12, 8%), resident interviews (4, 3%), and informative talks (2, 1%).

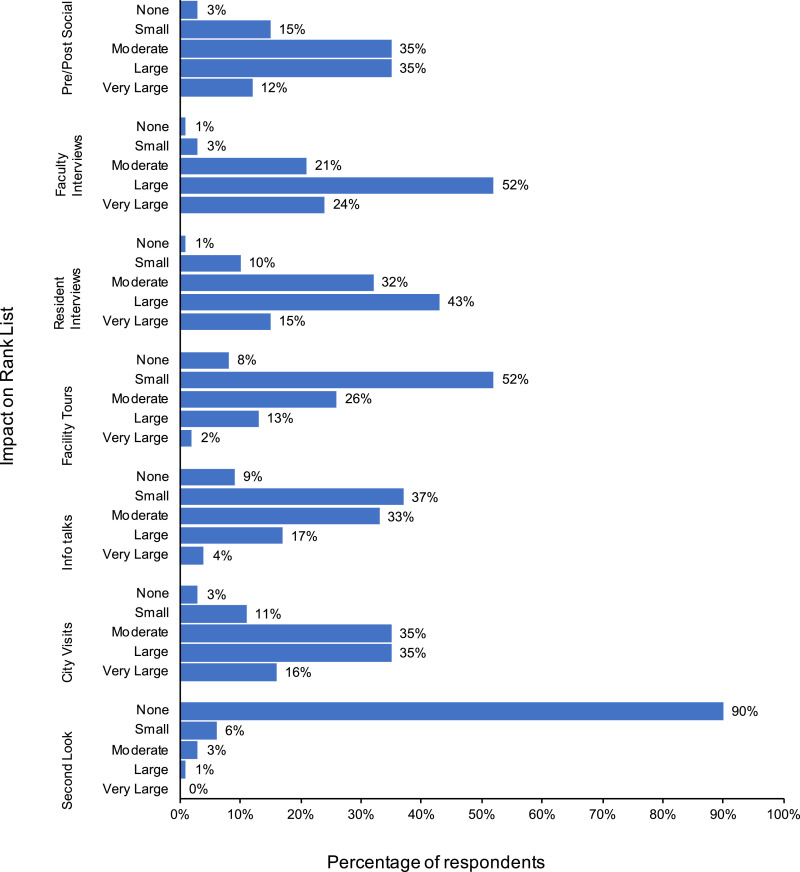

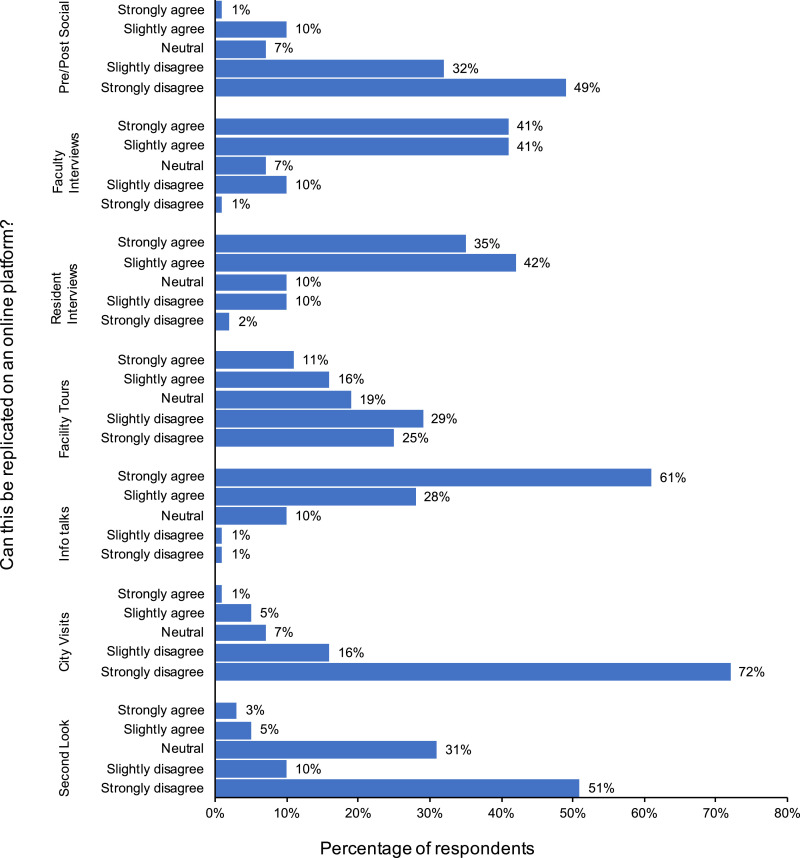

Pre/Postinterview Socials

With regards to the pre/post interview socials, 71 (46%) of respondents reported that the social events had a large or very large impact on their rank lists, while 54 (35%) reported a moderate impact, and 29 (18%) reported a small impact or no impact. One hundred twenty-six (81%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that the socials could be replicated on an online platform, while 11 (7%) were neutral, and 18 (12%) agreed or strongly agreed. Of the online video platforms, group video conferences were the one most commonly thought to be able to replicate a social (41, 26%), followed by scheduled one-on-one video conferences (27, 17%), and online games, such as Uno or Mario Kart, with residents (26, 17%).

Faculty Interviews

When asked about faculty interviews, 118 (76%) reported that they had a large or very large impact on their rank list, while 32 (21%) reported a moderate impact, and 5 (3%) reported a small impact or no impact. Interestingly, 127 (81%) agreed or strongly agreed that faculty interviews could be replicated on an online platform, while 10 (6%) were neutral, and 18 (12%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. The online platform thought to most effectively recreate faculty interviews was one-on-one video conferences (139, 89%), followed by group video conferences (7, 5%).

Resident Interviews

When asked about resident interviews, 89 (57%) reported that they had a large or very large impact on their rank list, while 49 (32%) reported a moderate impact, and 16 (10%) reported a small impact or no impact. One hundred nineteen (76%) agreed or strongly agreed that resident interviews could be replicated in an online platform, while 16 (10%) were neutral, and 19 (12%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. The online platform thought to most effectively recreate resident interviews was one-on-one video conferences (95, 61%), followed by group video conferences (47, 30%).

Facility Tours

When asked about facility tours, 23 (15%) reported that they had a large or very large impact on their rank list, while 40 (26%) reported a moderate impact, and 92 (59%) reported a small impact or no impact. Only 42 (27%) agreed or strongly agreed that facility tours could be replicated in an online platform, while 29 (19%) were neutral, and 83 (53%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. Premade videos were thought to the best online platform to recreate facility tours (107, 69%), followed by live-streamed videos (25, 16%).

Informative Talks

When asked about informative talks, 32 (21%) reported that they had a large or very large impact on their rank list, while 51 (33%) reported a moderate impact, and 72 (46%) reported a small impact or no impact. The vast majority (137, 88%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that informative talks could be replicated in an online platform, while 15 (10%) were neutral, and 2 (1%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. Interestingly, live-stream videos were thought to be slightly better than premade videos for informational talks (86, 55% vs 69, 44%).

City Visits

When asked about visiting the city of the program, 80 (51%) reported that they had a large or very large impact on their rank list, while 54 (35%) reported a moderate impact, and 21 (14%) reported a small impact or no impact. Only 8 (5%) agreed or strongly agreed that a city visit could be replicated in an online platform, while 11 (7%) were neutral and 136 (87%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. A premade video was thought to be better than a live-stream video to replicate a city tour (65, 42% vs 4, 3%).

Second Looks

If interviews were to be virtual, 70 (45%) of respondents would want in-person second looks to be allowed, while 58 (37%) would not want them to be allowed, and 28 (18%) were unsure. Notably, only 9 applicants (6%) actually went on second looks during their application cycles.

Match Day

When asked about moving Match Day to March to align with other specialties through the National Residency Match Program (NRMP), 65 (42%) opposed the idea, 63 (40%) supported it, and 28 (18%) were unsure.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to collect data regarding the application process in the COVID-19 era with the intention of extrapolating guiding principles and recommendations for the upcoming interview season. We found that, with knowledge of the COVID-19 era and the application process, respondents were split regarding whether or not subinternships should be allowed, and most applicants would prefer in-person interviews over virtual interviews. These finding appears to be driven by the importance of resident-applicant interaction and, to a lesser extent, urology applicants’ desire to visit the city in which they could potentially spend 5 or 6 years of their lives. While away rotations and in-person interviews most likely will not be allowed this year, there is still much uncertainty in terms of how to best replicate each component of the application process virtually. This study can serve as a guide for residency programs based on the input of applicants.

Visiting subinternships factor into this complicated picture in a number of different ways. According to the crowd-sourced data compiled by urology applicants over the past 3 matches, approximately 1 of 3 applicants matched into a nonhome program in which they spent time as a visiting subintern. Pagano et al. demonstrated that an honors grade on a subinternship was a predictor of matching into Urology.13 Similarly, a survey of program directors demonstrated that 87% said that completing an away rotation at their institution was an important factor in assessing the applicant.4 These authors also noted the importance of letters of recommendation, which are traditionally obtained during visiting rotations. In light of the findings that visiting subinternships significantly influence match outcomes, it is not entirely surprising that more respondents felt that visiting subinternships should not be cancelled (45%) than should (28%). The likely lack of in-person visiting subinternships in 2020 may inhibit applicants’ ability to assess programs and vice versa.

Applicants view the opportunity to have in-depth exposure to a program through subinternships as enormously beneficial, with good reason. It will be important for programs to find a way to salvage aspects of the subinternship experience, possibly through virtual visiting experiences, as this is extremely valuable to the candidates. We applaud the residency programs have already developed a system to allow medical students from other programs to give virtual grand rounds. While this is an important aspect of the visiting subinternship, it cannot replace the experience of working directly with residents and faculty in the operating rooms, wards, and clinics. While the SAU and individual programs are researching more holistic virtual subinternships, it is unclear the exact role they will play in the 2020-2021 match cycle. We propose that medical students be allowed to spend multiple months rotating at their home programs to allow them to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, personality, and growth over time and at least secure meaningful letters of recommendation. We would further encourage programs to be mindful of the ways in which lack of subinternship opportunities affect candidates when making interview and ranking decisions.

Our finding that the most important aspect of the interview process for applicants (64%) is resident-applicant interaction comports with previously reported survey results.2 , 5 What distinguishes this aspect of the interview process is the notion that these cannot be replicated virtually. Eighty-one percent of respondents disagreed with the sentiment that the pre/postinterview social event with residents could be simulated through virtual means, including informal platforms such as online games. Our study found that group video conferences would most closely replicate resident socials. A number of commenters noted that this could best be accomplished in smaller groups of 3-4 residents. We believe this to make intuitive sense and to represent a best practice, as a virtual meeting of a larger number of residents (eg, >10) could be intimidating and chaotic for applicants and not allow time for meaningful discussion. Given that only virtual interviews are likely to be permitted, greater efforts to allow interactions with current residents in a nonstressful environment, perhaps even outside of the interview day, should be explored.

Faculty interviews were found to be the second most important aspect of the interview process. Unlike resident interactions, however, 81% of urology applicants believe that this process can be replicated virtually. The vast majority (89%) of these respondents felt that scheduled one-on-one videoconference interviews would be the best medium for this portion of the interview.

Survey respondents were less optimistic about the ability of online platforms to replicate the experience of visiting a city. Eighty-six percent said that in-person visits had a moderate, large, or very large impact on their rank list and a large majority (87%) said this could not be replicated virtually. Prior analysis has shown that 95% of residency applicants stated that the geographic location of a residency affected their program preferences.11 A survey of the 2016 AUA Match applicants found that geography was among the most important factors applicants considered when evaluating a program.5 A recent analysis of the 2018-2019 match demonstrated that 65% of applicants matched at a program outside of the region of their medical school.12 It is possible that the interview process introduces some applicants to geographic locations that they may not have previously seen or considered. The impact of this void on applicants’ choices will likely be significant. Our study found that prerecorded videos would most closely replicate in-person city visits. Residency programs should invest sufficient time to create resources such as this that give accurate representations of their cities, including housing options.

As for informational talks, we recommend live-streamed talks based on a majority of our survey responses. While a large number of respondents were amenable to premade information sessions, it is possible that the interactive elements could make the experience more authentic for the applicants. (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 )

Figure 1.

Applicant views on away rotations, March match day, and second looks for the upcoming 2020-2021 match application cycle. (Color version available online.)

Figure 2.

Impact of various aspects of application cycle on applicants’ rank lists. (Color version available online.)

Figure 3.

Applicant views on if certain aspects of the application cycle can be replicated on an online platform. (Color version available online.)

The attitudes regarding second looks were polarized in the COVID-19 era. Despite the fact that second looks have been discouraged by SAU-AUA guidelines,14 45% of respondents thought that second looks should be allowed (10% felt it should be allowed and encouraged in the COVID-19 era) vs 37% who felt that they should not be allowed. Of note, only 6% of these applicants had done a second look during their application cycles. It is possible that the respondents believe that interviews are likely to be conducted virtually and they believe second looks could supplement that process. The question of second looks generated the most comments, with a number of respondents noting expense and equity issues. One commenter noted that second looks “put those who cannot afford them at a disadvantage and would make everyone feel like they have to do them.” Another noted that “it's still a burden for those who have neither the time, money, or immune system to support travel during an already uncertain time.” Other commenters noted that interviewees could feel pressured to visit sites to demonstrate interest, thus potentially offsetting any benefits of virtual interviewing. The most common objection expressed to second looks is the perceived advantage conferred by visiting a program. Several respondents noted the public health risk of allowing this form of travel.

We believe a low-stakes, second look could be reasonable under certain circumstances in the COVID-19 era, given our respondents’ preferences. What is critical, however, is the clear separation of this process from the match process itself. One way this could be accomplished is by having programs submit rank lists before applicants and having an extended length of time between submission of program and candidate list submission. If state travel restrictions ease as case counts decline and institutions allow visitors, it would be reasonable to extend the duration of this time period for the purpose of second-look contact, based on our findings. This period could be deemed a “second-look window” and be the only period of time in which postinterview contact and visitation are allowed. This would eliminate the primary perceived advantage to second looks, an increased chance of matching at a program, and remove any incentive for applicants to visit other than to inform their own preferences, should they deem the risk of travel acceptable. This solution would also solve the issue of city visits not being easily replicated virtually. We recognize that this potential solution is not entirely without equity issues associated with cost and geographic origin of candidates, as travel from some regions of the country to others is currently banned. This would give some candidates access to greater information about their potential landing spots than others.

This study has a number of important strengths. It is the first study in the COVID-19 era evaluating urology applicants’ attitudes toward the interview process. The overall number of respondents is sufficient to derive a meaningful understanding of attitudes toward the process. Additionally, the survey population is uniquely positioned to answer these questions, as they have the benefit of being the 2 classes for whom the process is most recent, but unlike new applicants for the upcoming cycle, these respondents have a detailed knowledge about the process of residency interviews.

The converse perspective, that those surveyed are not the direct stakeholders for the upcoming interview cycle, is a valid critique of our study. We sought to obtain meaningful and generalizable data quickly to guide decisions in this rapidly evolving environment. Seeking out applying medical students would have significantly delayed our findings and possibly have left us with a selection bias, as the applicant cohort has not yet been firmly delineated.

Given current realities, we recognize that, in spite of attitudes favoring in-person interviews, the entire process will be virtual this upcoming year. Thus, it is incumbent on programs to be sensitive to this perspective and make extraordinary efforts to accommodate requests for information and informal, low-stakes interactions with residents in the program.

CONCLUSION

In the COVID-19 era, urology applicants feel that faculty interviews can be replicated virtually, while resident interactions, which are the most important driver of applicant rank lists, cannot. Given there will not be in-person subinternships, steps such as a low-stakes, post rank-list submission by programs “second-look window” (prior to applicant list submission) and small virtual encounters with residents could alleviate applicant concerns about the 2020-2021 interview cycle.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.072.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khouri RJ. The applicants’ perspective on the urology residency match process. Urol Pract. 2019;6:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of American Medical Colleges. Coronavirus and The VLSO Program. Available at:https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/coronavirus-covid-19-and-vslo-program/. Accessed May 17, 2020

- 4.Weissbart SJ, Stock JA, Wein AJ. Program directors’ criteria for selection into urology residency. Urology. 2015;85:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebastchi AH, Khouri RK, McLaren ID, et al. The urology applicant: an analysis of contemporary urology residency candidates. Urology. 2018;115:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association AU. Urology Residency Match Statistics.

- 7.Electronic Residency Application Service. ERAS 2021 Residency Timeline; 2020. Available at: https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/article/eras-timeline-md-residency/. Accessed May 17, 2020

- 8.The Coalition for Physician Accountability's Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021 Moving Across Institutions for Post Graduate Training . U.S. Osteopathic, and Non-U.S. Medical School Applicants; 2020. Final Report and Recommendations for Medical Education Institutions of LCME-Accredited. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of American Medical Colleges. Conducting Interviews During the Coronavirus Pandemic.; 2020. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/conducting-interviews-during-coronavirus-pandemic. Accessed May 17, 2020

- 10.Society of Academic Urologists. Issues Addressing Applicants & Training Program During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available at:https://sauweb.org/about/announcements/coalition-of-physician-accountability-recommendati.aspx. Accessed May 17, 2020

- 11.Nuthalapaty FS, Jackson JR, Owen J. The influence of quality-of-life, academic, and workplace factors on residency program selection. Acad Med. 2004;79:417–425. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anwar T, Wakefield M, Murray KS. The role of geography in the AUA residency match. J Urol. 2020;203:1070–1071. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagano J, Cooper K, McKiernan J, Badalato G. Outcome analysis of factors impacting the urology residency match. Urol Pract. 2016;3:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Society of Academic Urologists. Residency Match Process Policy and Guidelines; 2020. Available at: https://sauweb.org/resources/resident-match-process.aspx. Accessed May 17, 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.