Abstract

Objective:

Previous research indicates a potential relationship between rurality and suicide, indicating that those living in rural areas may be at increased risk of suicide. This relationship has not been reviewed systematically. This study aims to determine whether those living in rural areas are more likely to complete or attempt suicide.

Method:

This systematic review and meta-analysis included observational studies based on people living in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Data sources included PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar from January 2006 to December 2017. Studies must have compared rural and urban suicide or suicide attempts. Nonprimary research articles were excluded.

Results:

A total of 6,259 studies were identified and 53 were included. Results indicate that males living in rural areas are more likely to complete suicide than their urban counterparts (RR = 1.41, 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.64, I 2 = 96%). Females in rural areas are not significantly more likely to complete suicide (RR = 1.16, 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.37, I 2 = 79%). Among studies that only reported combined estimates, rural individuals are more likely to complete suicide (RR = 1.22, 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.33, I 2 = 98%). There is no association found between rurality and suicide attempts (RR = 0.93, 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.19, I 2 = 85%).

Conclusions:

Those living in rural areas are more likely to complete suicide, with some studies indicating that only rural males are more likely to complete suicide; these findings are relatively consistent across all four countries. Public health initiatives should aim to overcome geographic variation in completed suicide, with a particular focus on rural males.

Keywords: suicide, rural, suicide attempt, systematic review

Abstract

Objectif :

La recherche antérieure suggère une relation potentielle entre la ruralité et le suicide, indiquant que les personnes habitant en milieu rural peuvent être à risque accru de suicide. Cette relation n’a pas été examinée systématiquement. La présente étude vise à déterminer si les personnes en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de compléter ou de tenter un suicide.

Méthode :

Cette revue systématique et cette méta-analyse comportaient des études par observation basées sur des personnes habitant le Canada, les États-Unis, le Royaume-Uni et l’Australie. Les sources des données étaient notamment PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, et Google Scholar de janvier 2006 à décembre 2017. Les études doivent avoir comparé le suicide rural et urbain ou les tentatives de suicide. Les articles de recherche non primaire étaient exclus.

Résultats :

Nous avons identifié 6,259 études et 53 ont été incluses. Les résultats indiquent que les hommes vivant en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de compléter un suicide que leurs homologues urbains (RR = 1.41 [IC à 95% = 1.21 à 1,64, I 2 = 96%]). Les femmes en milieu rural ne sont pas significativement plus susceptibles de compléter un suicide (RR = 1.16 [IC à 95% = 0.98 à 1.37, I 2 = 79%]). Parmi les études qui ne rapportaient que des estimations combinées, les personnes en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de compléter un suicide (RR = 1.22 [IC à 95% = 1.11 à 1.33, I 2 = 98%]). Aucune association n’a été constatée entre la ruralité et les tentatives de suicide (RR = 0.93 [IC à 95% = 0.73 à 1.19, I 2 = 85%]).

Conclusions :

Les personnes vivant en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de compléter un suicide, certaines études indiquant que seuls les hommes en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de compléter un suicide. Ces résultats sont relativement constants dans les quatre pays. Les initiatives de santé publique devraient tendre à surmonter la variation géographique du suicide complété, en mettant l’accent sur les hommes en milieu rural.

Introduction

Over 800,000 people die from suicide worldwide each year.1 For every completed suicide, there are many more suicide attempts. Differences in suicide rates across the rural–urban continuum have been observed in studies across many countries including Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom (UK).2–7 The reason for this rural–urban disparity is unknown, but several theories have been proposed such as physical and social isolation, access to firearms, decreased access to mental health and other health services, attitudes or stigma toward mental illness and help-seeking behaviors, and misclassification of cause of death.2,3,8 The association between rurality and suicide has not been systematically reviewed to date.

The primary objectives of this review are to determine (1) whether those living in rural areas are more likely to complete suicide than those living in more urban areas and (2) whether those living in rural areas are more likely to attempt suicide than those living in more urban areas. It is hypothesized that those living in rural areas are more likely to complete suicide and attempt suicide than those living in more urban areas. The secondary objectives of this review are to determine (1) whether, among those who attempt or complete suicide, individuals living in rural areas are more or less likely to seek help from general practitioners and mental health practitioners; (2) whether, among those who attempt or complete suicide, individuals living in rural areas are more or less likely to have a diagnosis of mental illness; and (3) finally, whether suicide methods differ between those living in rural and urban populations. It is hypothesized that those living in rural areas are less likely to seek help, less likely to have a diagnosis of mental illness prior to suicide, and more likely to use firearms methods than those living in more urban areas.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis. The study population consists of people living in high-income English-speaking countries, determined by the country’s official or national language. High-income countries (defined as ranking within the top 10 countries based on gross domestic product)9 were selected because, although global rates of suicide are decreasing, suicide rates are increasing among some of these English-speaking high-income countries, particularly the United States.10,11 These countries have similar demographics, having all experienced a post–World War II baby boom, and currently have aging populations.12 Previous literature suggests that cultural norms affect suicide rates in urban versus rural settings, and this review aims to focus on a more homogenous subset of countries.7,13 National language was selected as an inclusion criteria because culture and language are known to be inseparable and intimately connected.14

Both published and unpublished literature were included in the search; there were no language restrictions. Publications were restricted to those published from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2017.

The exposure of interest is living in a rural area. Common definitions of rurality are based on population density, distance to urban centers, and distance to health-care services.3,6,15,16 Primary outcomes are completed suicide and attempted suicide. These outcomes may occur at any point in time following the occurrence of the exposure (i.e., moving to or living in a rural area). Secondary outcomes are help-seeking behavior, mental illness detection, and suicide methods. Help-seeking behavior is defined as seeking help from a physician or specialist prior to suicide or suicide attempt. Mental illness detection is defined as having any mental health–related diagnosis (including substance use disorders) captured prior to suicide or suicide attempt. Methods of suicide included any categorization of suicide method, including poisoning, hanging, and firearms.

All types of observational studies including both prospective and retrospective cohort designs, case control, and cross-sectional studies were included in the review. Nonprimary research articles such as letters, reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, and commentaries were excluded. Conference abstracts and articles written in languages other than English were eligible for inclusion.

The databases searched were PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. Search terms included “suicide(s)(al),” “self harm,” “self mutilation,” “automutilation,” “rural(ity),” “frontier,” “farm(s),” “agriculture(al),” adding similar terms together with the “OR” or “AND” operators. Medical subject headings terms of the above search terms were also used if a database used similar indexing terms. The search interface was Ovid. Google Scholar was used to find gray literature.

Data Analysis

The study selection procedure was to first remove all duplicates and then screen all citations that resulted from the combination of search terms. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or that met exclusion criteria were excluded. A second researcher applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen a random selection of 500 of the titles and abstracts in order to validate the selection process resulting in an agreement score (κ statistic) of 0.81, which is considered to be strong.17 Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Next, full text articles were reviewed. All criteria were assessed, and a single failed eligibility criterion resulted in exclusion. Subsequently, data extraction was done, where a second researcher performed the data extraction for a minimum of 10% of the total number of included studies to ensure that extraction was acceptable. Data included study characteristics (e.g., study population) and point estimates.

Planned subgroup analyses included analysis by definition of rurality (studies that use a definition that accounted for population density vs. those that did not and those that accounted for distance to urban centers vs. those that did not). Subgroup analyses were also planned based on publication year and risk of bias.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing bias in observational studies.18,19 This scale uses a star system that assesses selection and comparability of study groups and exposure and outcome ascertainment. The highest score attainable is 9 stars, indicating the lowest risk of bias. Risk of bias is summarized for each study’s primary outcome across all domains of bias, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook.20 The risk of bias tool does not asses bias across the entire study but only for the urban–rural comparison for suicide or suicide attempts.

The synthesis includes both a narrative review and a meta-analysis conducted by Review Manager Version 5.3 by outcome and by country. Only studies that report an effect estimate with confidence intervals or standard error were included in the meta-analyses, and the exposure measure for rurality had to be categorical or binary. The generic inverse variance method was used because most studies report rate ratios and do not report dichotomous outcomes.20 This method assigns a weight to the relative study estimate (e.g., the relative rate) that is equal to the inverse of the variance of the effect estimate. The analysis model selected is the random effects model because it is not assumed that there is one true effect size.21 For each study, the most recent effect estimate comparing the most rural to the most urban is used. Odds ratios were interpreted as risk ratios for the purposes of the meta-analysis because the outcomes of interest are rare. This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO: CRD42016049310.

Results

Literature Search

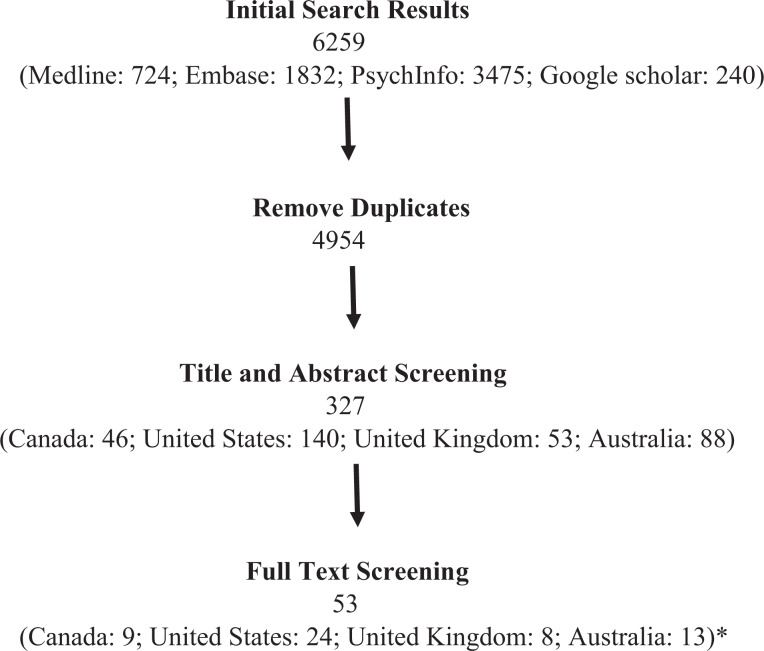

The initial search terms resulted in 6,259 citations, and 4,954 citations after removing duplicates (Figure 1). Following the primary screening of titles and abstracts, 327 articles were reviewed in full text. Following the secondary review of full text articles, 53 studies were found to be consistent with the aims of this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Search Results. *Two papers include analyses for both Canada and Australia.

Outcome: Completed Suicide

Of the studies included in the final review, 36 studies examined completed suicide by rural versus urban status (Supplemental Table 1). Of these, 30 studies suggest that those living in rural areas have a higher risk of completed suicide, with 12 of these indicating that only rural males have an increased risk of suicide. Only 6 studies do not show increased risk of completed suicide with increasing rurality. Three of these studies are from Canada, while the other three are from each of the other countries. Two of these studies indicate that urban individuals have a higher risk. Of these two, one examines only oxycodone-related suicides.

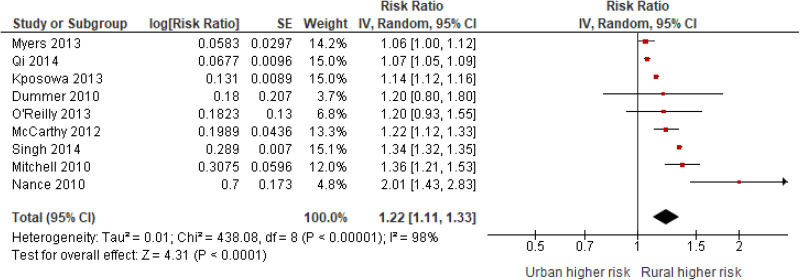

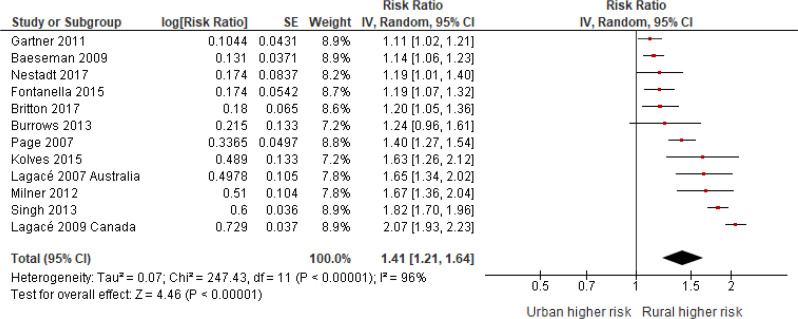

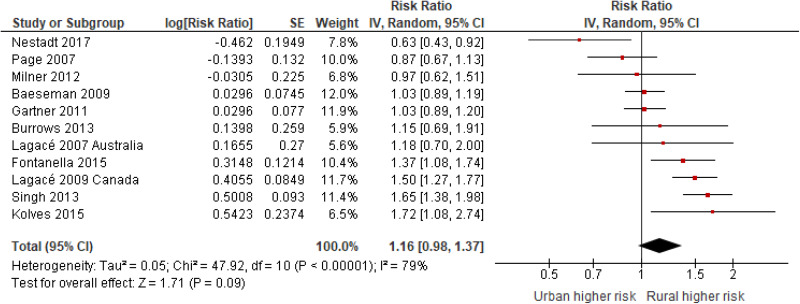

The meta-analysis (Figure 2) indicates that among those studies which report suicide for the entire population (male and female combined), suicide is higher among rural populations (RR = 1.22, 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.33, I 2 = 96%). Among those that report estimates for males, rural males are more likely to complete suicide than urban males (RR = 1.41, 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.64, I 2 = 98%; Figure 3). Among those that report estimates for females, rural females are not significantly more likely to complete suicide than urban females (RR = 1.16, 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.33, I 2 = 79%; Figure 4). Findings appear to be relatively consistent across countries (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 2.

Completed suicide by urban–rural status (general population).

Figure 3.

Completed suicide by urban–rural status (males).

Figure 4.

Completed suicide by urban–rural status (females).

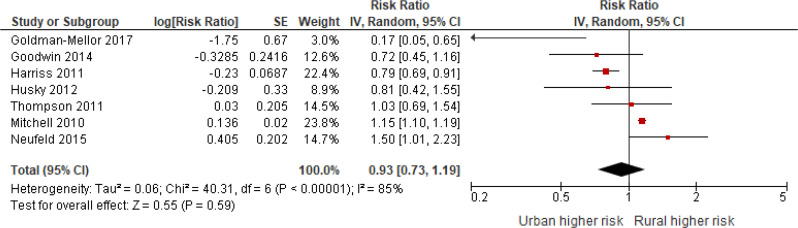

Outcome: Suicide Attempt

Of the studies included in this review, 11 studies examine suicide attempts by rural–urban status (Supplemental Table 2). Of these, 3 suggest that rural areas have higher rates of suicide attempts, and 1 suggests that only rural females have higher rates. Three studies indicate that urban dwellers have a higher risk of suicide attempts, while four studies do not indicate that there are rural–urban differences. The meta-analysis indicates that there are no differences between rural and urban areas in terms of suicide attempts (RR = 0.93, 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.19, I 2 = 85%; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Suicide attempt by urban–rural status.

Secondary Outcomes

Six of the eight studies examine help-seeking behavior prior to completed suicide rather than prior to a suicide attempt (Supplemental Table 3). Findings are mixed, with 4 studies indicating that rural individuals are less likely to seek help, and 4 studies indicating no significant differences.

Six studies examine mental illness diagnoses prior to suicide (Supplemental Table 4). Three studies from the United States and Canada indicate that rural individuals are less likely to have a prior diagnosis. The 2 studies from the UK have mixed results, and the 1 study from Australia indicates that those living in rural areas are more likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis.

The 10 of 11 studies that examine suicide methods indicate that those living in rural areas are more likely to use firearms than those living in urban areas (Supplemental Table 5). There is also some evidence to suggest that rural dwellers may be more likely to use hanging and significantly less likely to use poisoning.

Subgroup Analyses

Risk of bias assessment scores range from 1 to 8 stars of a possible 9 stars (Supplemental Table 7). A subanalysis that excludes studies with a score of 5 or less did not change the results of the meta-analysis for any of the outcomes. A comparison of studies that do and do not include population density and those that do and do not include distance to urban centers in the definition of rurality did not show different results for any of the outcomes. When comparing studies that were published in 2013 and later with those published prior, the significance and direction of all associations remained the same.

Discussion

Overall, the results suggest that rurality is associated with increased risk of completed suicide. Furthermore, the results suggest that sex may be an effect modifier of this association, with rural males being at greater risk of suicide than urban males, while females may be at a similar risk, regardless of residence. Results also indicate no significant relationship between rurality and suicide attempts, although this may vary by country. These findings are in agreement with previous narrative literature reviews by Hirsch et al., which suggest suicide rates may be higher among rural people in these countries.6,7 However, these reviews did not find a potential interaction by sex, where males may be at an increased risk.

The rural–urban differences may be a result of lack of access to health care. There is some evidence in this review that those living in rural areas may be less likely to seek help and less likely to have a mental health–related diagnosis, which occurs in the context of health service use. Those living in rural areas may be less likely to seek help due to distance to care or stigma. Findings also indicate that those living in rural areas are more likely to use firearms, which is a more lethal means of suicide, and possibly less likely to use poisoning, which is a less lethal means.22 This may also be partially mediating the relationship between rurality and completed suicide.

One possible reason for the sex effect modification is less access to formal mental health care in rural areas. This lack of access may be more detrimental to males in rural areas because emotionally supportive relationships are substantially more protective against major depression for women than for men.23 Another potential explanation is that males in rural areas are likely to be employed in occupations such as farming or forestry, which are associated with higher risk of suicide.24 Further research examining both suicide and suicide attempts by sex could help clarify this relationship.

This study has several limitations. First, is that some studies only examine suicide among specific subsets of the general population, resulting in high heterogeneity among studies. For example, of the 2 studies using a Canadian population which examined rural–urban suicide attempts, the 2 study populations were students ages 12 to 17 and adults over the age of 60 living in a home care setting.25,26 There was a high degree of heterogeneity between studies. Furthermore, the definition of rurality differs among studies, and this also introduces heterogeneity. Therefore, while this study can give a general direction in which this association lies, the final effect estimates should be interpreted with caution. Forest plots are helpful visual indicators of the general trends across studies. Second, potential confounders are addressed differently across studies, and there is a high possibility of unmeasured residual confounding. A third limitation is that there were few studies that examined secondary outcomes by rural–urban status. No studies examined whether these indicators of care mediate the relationship between rurality and suicide. These outcomes should be examined more focally with adjustment for confounders and exploration of potential effect modifiers such as sex.

This study also has strengths. By examining suicide across 4 countries, a large number of studies were included in the meta-analysis, increasing the power of the findings. Second, this review identified a number of limitations of the existing research on this topic. For example, Australia, Canada, and the UK each have 2 or fewer studies that examine rural–urban differences in suicide attempts, and most of these are for smaller subpopulation (e.g., youth). Further research is needed to clarify this association. Many studies use older data that may not reflect the current relationship between rurality and suicide outcomes. For example, the most recently published data on completed suicide in Canada by urban–rural status use data that were collected from 2000 to 2005, while the most recent study on suicide across all ages uses data from 1986 to 1996.27,28 Future research should use more recent data as this would help inform policy and lead to solutions that are most relevant.

It is important to consider how public health initiatives and clinical practice can be used to reduce this rural–urban disparity. Our systematic review shows that those living in rural areas are at increased risk of suicide in comparison to their urban counterparts and that this association is particularly strong among males. Family physicians and psychiatrists practicing in rural areas or in urban areas with rural catchment areas should be aware of this important risk factor when assessing their patients’ overall risk of suicide. Medical professionals involved in education should be aware of this risk factor when educating family physicians in rural communities as well as gatekeepers in rural communities (e.g., teachers, police officers, spiritual leaders). Public health campaigns focused on suicide prevention that currently only target urban areas should consider how they can reach rural populations as well.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that rurality is associated with completed suicide and that rural males have a higher likelihood of dying by suicide compared to urban males. Future research should always consider sex as a potential effect modifier of the association between rurality and suicide-related outcomes. Potential mediators of this disparity must be examined to determine why these differences exist and to help formulate targeted interventions and policies to reduce suicide among those living in rural areas.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary_tables_revised_clean for Rurality and Risk of Suicide Attempts and Death by Suicide among People Living in Four English-speaking High-income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Rebecca Barry, Jürgen Rehm, Claire de Oliveira, Peter Gozdyra and Paul Kurdyak in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Omer Syed Muhammad Hasan and Bethany R. Chrystoja for acting as second reviewers.

Footnotes

Data Availability: All data were collected from publicly available sources.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The first author was personally funded by the CIHR Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, and other funding was provided by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

ORCID iD: Rebecca Barry, MSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6647-2703

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6647-2703

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. The World Health Organization. Suicide; 2018. [accessed 2018 Nov 7]. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- 2. Searles VB, Valley MA, Hedegaard H, Betz ME. Suicides in urban and rural counties in the United States, 2006-2008. Crisis. 2014;35(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fontanella CA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Phillips GS, et al. Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996-2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):466–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Judd F, Cooper A-M, Fraser C, Davis J. Rural suicide—people or place effects? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(3):208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCarthy M. Youth suicide rate in rural US is nearly double that of urban areas, study finds (editorial). BMJ. 2015;350:h1376–h1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsirsch JK. A review of the literature on rural suicide: risk and protective factors, incidence, and prevention. Crisis. 2006;27(4):189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirsch JK, Cukrowicz KC. Suicide in rural areas: an updated review of the literature. J Rural Ment Heal. 2014;38(2):65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson H, Judd F, Komiti A, et al. Mental health problems in rural contexts: What are the barriers to seeking help from professional providers? Aust Psychol. 2007;42(9):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Phelps G, Crabtree S. Worldwide, median household income about $10,000. Gallup. 2013;3(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Case A, Deaton A. Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Pap Econ Act. 2017;2017:397–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(241):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Bavel J, Reher DS. The baby boom and its causes: what we know and what we need to know. Popul Dev Rev. 2013;39(2):257–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu P, Huang X, Tsang AKT, et al. Developing a matrix model of rural suicide prevention. Int J Ment Health. 2011;40(4):28–49. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang W. The relationship between culture and language. ELT J. 2000;54(4):328–334. doi:10.1093/elt/54.4.328. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Rev. 2000;67(2):33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yip PSF, Callanan C, Yuen HP. Urban/rural and gender differentials in suicide rates: East and West. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(1-3):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses; 2012. [accessed 2018 Dec 14]. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 19. Patra J, Bhatia M, Suraweera W, et al. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]; 2011. [accessed 2016 July 12]. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 21. Michael B, Hedges L, Rothstein H. Meta-analysis: fixed effect vs. random effects; 2007. [accessed 2018 Nov 20]. https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/M-a_f_e_v_r_e_sv.pdf.

- 22. Elnour AA, Harrison J. Lethality of suicide methods. Inj Prev. 2008;14(1):39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kendler K, Myers J, Prescott C. Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD. Suicide by occupation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(6):409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bethell J, Bondy SJ, Lou W, Guttman A, Rhodes AE. Emergency department presentations for self-harm among Ontario youth. Can J Public Health. 2013;104(2):124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neufeld E, Hirdes P, Perlman M, Rabinowitz T. A longitudinal examination of rural status and suicide risk. Healthc Manage Forum. 2015;28(4):129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ostry AS. The mortality gap between urban and rural Canadians: a gendered analysis. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(4):1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lagacé C, Desmeules M, Pong RE, Heng D. Non-communicable disease and injury-related mortality in rural and urban places of residence. Can J Public Heal. 2007;98(Suppl 1):S62–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary_tables_revised_clean for Rurality and Risk of Suicide Attempts and Death by Suicide among People Living in Four English-speaking High-income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Rebecca Barry, Jürgen Rehm, Claire de Oliveira, Peter Gozdyra and Paul Kurdyak in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry