Abstract

The acidic microenvironments of tumor tissue and cells provide an opportunity for the development of pH-responsive drug delivery systems in cancer therapy. In this work, we designed a calcium carbonate (CaCO3)-core-crosslinked nanoparticle of methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(l-glutamic acid) through mineralization for intracellular delivery of doxorubicin (DOX), referred to as CaNP/DOX. CaNP/DOX exhibited high drug loading capability, uniform nanoparticle size, and pH-dependent DOX release. In the meantime, the enhanced cell uptake, superior cytotoxicity toward mouse osteosarcoma K7 cells, extended circulation half-life, and improved accumulation of DOX in K7 allograft tumor from CaNP/DOX were also demonstrated. More interestingly, CaNP/DOX displayed improved antitumor effect and reduced side effects against the K7 osteosarcoma-allografted mouse model and the 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mouse model. Given the superior properties of Ca-mineralized polypeptide nanoparticle for intracellular drug delivery, the smart drug delivery system showed strong competitiveness in clinical chemotherapy of cancers.

Keywords: Polypeptide, Calcium mineralization, Controlled drug release, pH-responsiveness, Osteosarcoma chemotherapy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A doxorubicin-loaded calcium carbonate-crosslinked polypeptide nanoparticle (CaNP/DOX) is prepared by mineralization.

-

•

CaNP/DOX with high drug-loading efficiency and uniform nanoparticle size is developed for intracellular drug delivery in osteosarcoma chemotherapy.

-

•

CaNP/DOX exhibits prolonged circulation half-life and upregulated intratumoral accumulation.

-

•

CaNP/DOX shows enhanced antitumor efficacy and reduced side effects toward subcutaneous and orthotopic osteosarcoma models in mice.

-

•

CaNP/DOX demonstrates great potential in the clinical chemotherapy of various cancers.

1. Introduction

Tumors are characterized by the mad growth of internal malformed blood vessels and severe hypoxia in tissues and cells [1]. In this situation, tumor cells acquire energy via the glycolysis pathway, which leads to massive production and accumulation of lactic acid and the formation of the acidic tumor microenvironment [1,2]. Taking advantage of this tumor-specific property, researchers have developed diverse pH-responsive drug delivery systems based on organic, inorganic, or hybrid nanomaterials to improve the delivery of antitumor drugs in the tumor site with the enhanced efficacy and reduced systemic toxicity [3].

Polymer nanocarriers, as a typical kind of organic nanomaterials, play a vital role in tumor-targeted drug delivery, owing to their unique properties, such as excellent biocompatibility, various chemical structures and functions, and facile modification [4]. Generally, there are mainly two kinds of tumor acidity-sensitive drug delivery nanoplatforms prepared from polymers with exposed protonatable−deprotonizable groups [5] or pH-trigged linkages [6]. The protonatable groups in the acidic tumor microenvironments include amino [7], imidazolyl [8], sulfonamide [9], and carboxyl groups [10]. The protonation of the functional groups induces the swelling or shrinking of nanocarriers and accelerates the payload release when exposed to the acidic intratumoral or intracellular medium [11]. The acid-labile chemical bonds, such as vinyl ether [12], benzoic imine [13], β-carboxylic amides [14], and acetal bond [15], are cleaved in the acidic microenvironments of the tumor tissue or cells and promoting the release of loaded drugs.

The pH-sensitive inorganic nanomaterials have also been widely studied as controlled drug delivery vehicles to the tumor tissue or cells, including calcium phosphate (CaP) [16] and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) [17], because of their superior property of acidity-triggered disintegration. More recently, the hybrid nanomaterials combining organic and inorganic components have received increasing attention as benefit their combination advantages [18]. For example, Mao et al. prepared CaCO3-crosslinked methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(l-glutamic acid) (mPEG-b-PGA) micelle for delivery of macrophage colony-stimulating factor, which showed significant antitumor effect through the immune pathway [19]. Xie and colleagues developed a composite nanoparticle of PEG-grafted carboxymethyl chitosan and CaP by nanoprecipitation and nanomineralization, enabling siRNA to be transported safely in vivo and silencing tumor-promoting gene effectively [20]. In addition, Ding and coworkers developed the doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded hyaluronate-CaCO3 hybrid nanoparticle using a “green” method, which proved to be capable of rapidly releasing DOX in the acidic tumor microenvironment and exhibited excellent antitumor efficacy [21].

Among diverse hybrid nanomaterials, the organic−inorganic hybrid nanoparticles based on the CaP/CaCO3 mineralization of various polymers have unique advantages as follows: (1) The nanoparticles are small in size, well dispersed in the median, and have the ability to deliver both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [22]; (2) The nanoplatforms are stable at physiological pH and sensitive to the acidic microenvironments of tumor tissue and cells, decomposing to Ca2+ and carbon dioxide (CO2) in acidic environments and alleviating the local acidic conditions simultaneously [23]; (3) The nanosystems exhibit outstanding biocompatibility and biodegradability, which are excreted easily from the human body [24].

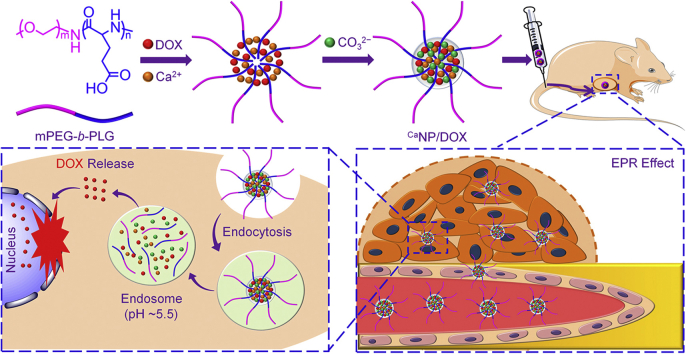

In this work, a Ca-mineralized mPEG-b-PGA nanoparticle (CaNP/DOX) with high loading efficiency and uniform size was developed to controlled release DOX in response to low pH in the cancer cells, as shown in Scheme 1. The physicochemical properties, cell internalization and toxicity, and metabolism and tumor inhibition in vivo of CaNP/DOX were characterized, and the results demonstrated its great promising in osteosarcoma chemotherapy.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration for fabrication, circulation in vivo, intratumoral accumulation, and pH-triggered intracellular drug release of CaNP/DOX.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

mPEG (number-average molecular weight (Mn) = 5,000 Da) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, P. R. China). The amino-terminated mPEG (mPEG-NH2) and γ-benzyl-l-glutamate N-carboxyanhydride (BLG NCA) were synthesized on the basis of our previous work [25]. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX·HCl) was purchased from Beijing Huafeng United Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, P. R. China). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were bought from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). Methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, P. R. China). Ki-67 and p53 antibodies were purchased from Abcam Company (Cambridge, UK). The purified deionized water was prepared by the Milli-Q plus system (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA, USA). All the other solvents and reagents were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, P. R. China).

2.2. Preparation of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX

mPEG-b-PGA was synthesized according to our previous reports [26]. A dialysis technique made NP/DOX. In detail, thoroughly mix mPEG-b-PGA (100.0 mg) was thoroughly dissolved in 4.0 mL of deionized water at pH 8.0. Next DOX solution (10.0 mg, 2.0 mL) was added, and, the mixed solution was stirred under dark condition for 12 h. Unloaded drugs were excluded by the dialysis technique (molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) = 3,500 Da) for one day. NP/DOX was gained by lyophilization in a condition without light.

CaNP/DOX was prepared based on CaCO3 mineralization of the core of mPEG-b-PGA micelle [27]. Concretely, mPEG-b-PGA (100.0 mg) was dissolved in deionized water (4.0 mL) for 1 h. The pH of the obtained liquid was maintained at 8.0. Then, 2.0 mL of calcium nitrate (Ca(NO3)2) aqueous solution (17.03 mg, 0.73 mmol) was added with stirred ceaselessly (800 rpm) for 2 h. It was then mixed with DOX solution (10.0 mg, 2.0 mL) in darkness and kept stirring at 25 °C for 2 h. After that, 2.0 mL of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution (15.29 mg, 0.73 mmol) was trickled into the mixture. The molar concentration ratio of [Glu−]/[Ca2+]/[CO32−] was determined as 3:1:1. The agitation time of the mixed solution was extended to 12 h. The dialysis method (MWCO = 7,000 Da) was used in the subsequent operation to separate the unbound material. The dialysate was replaced every 4 h until the dialysate was colorless. The sample to be lyophilized was filtered and dispensed into a beaker. After lyophilization, the obtained final product was CaNP/DOX. The drug loading content (DLC) and drug loading efficiency (DLE) equations were calculated as our previous work [21].

2.3. Cell culture

The murine osteosarcoma K7 cell line and the human osteosarcoma 143B cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA). K7 cells and 143B cells were cultured DMEM supplemented with 10% (V/V) fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (50 IU mL−1), and streptomycin (50 IU mL−1) at 37 °C in 5% (V/V) carbon dioxide (CO2).

2.4. Flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy observation

The FITC-marked nanoparticles were carried out to K7 cells. 2 × 105 K7 cells per well were seeded in 6-well plate and incubated for 24 h, and then the original medium was replaced with free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX solution in DMEM at a final DOX concentration of 10.0 μg mL−1. The cells in the control group were treated with PBS. For flow cytometry (FCM) detection, the cells were further cultured at 37 °C for 2, 6, or 12 h, and then washed three times with PBS. The remaining cells were suspended in PBS and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were removed, and the cells were washed with PBS for removing the background fluorescence in the medium. The K7 cells were resuspended with 500.0 μL of PBS. Data were analyzed by a flow cytometer (FCM Beckman, California, USA). For confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) assay, after being incubated with DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX for 2, 6, or 12 h, the cells were washed and fixed with 4% (W/V) formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. And then, the cell nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue) for 3 min. The cell localization was visualized under an LSM 780 CLSM (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with 10× eyepieces and 20× objectives.

2.5. Establishment of orthotopic osteosarcoma model

4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories (Beijing, China). All animals were kept following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all experiments about the animals were permitted by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University. To establish an orthotopic osteosarcoma model, 20.0 μL of cell suspension containing 2.0 × 106 143B cells was injected into the right tibial bone marrow cavity of mouse. The first treatment was implemented when the volume of the tumor region was approaching 200 mm3. Free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX were injected by tail vein at consistently DOX dose (5.0 mg (kg BW)−1) on day 0, 4, 8, and 12. The control group was treated with PBS. The growth of osteosarcoma was recorded until four days after the last treatment. The volume of the orthotopic osteosarcoma region was calculated concerning Equation (1).

| (1) |

AP represented the value measured at the apex of the knee joint, and L represented the value measured along the longitudinal axis of the tibia.

2.6. Micro-CT scan

The sample of orthotopic osteosarcoma was fixed on a suitable stage, and the omnidirectional scanning was started after closing the device door. The rotation speed of the stage was adjusted to 0.6° per second. After the scan, CTvox software (Bruker Co.) was used for 3D reconstruction, and bone parameters were analyzed by CTAn software finally (Bruker Co.).

2.7. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis

The mice were sacrificed on the second day after the last intravenous (i.v.) injection. The tumor and main organs (i.e., the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were separated, fixed in 4% (W/V) PBS-buffered paraformaldehyde overnight, and then embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into slices for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical analysis (Ki-67, p53). The histopathological and immunohistochemical changes were detected by a microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Optical Apparatus Co., Ardmore, PA, USA) and subsequently analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Fabrication and characterizations of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX

mPEG-b-PGA was synthesized by the ring-opening polymerization of BLG NCA with mPEG-NH2 as a macromolecular initiator and then deprotection of the benzyl group in trifluoroacetic acid. The chemical structure was confirmed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectrum. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, the peaks of 3.74 (a) and 4.67 (b) ppm were attributed to the mPEG backbone (−CH2CH2−) and –C(O)CH(CH2−)NH− of PGA, respectively. Peaks of 2.00–2.14 (c) and 2.49 (d) ppm represented −(C(O))(NH)CHCH2CH2C(O)− and −(C(O))(NH)CHCH2CH2C(O)− on the GA side chain.

For NP/DOX, DOX was loaded into the polymer core through electrostatic interaction between the carboxyl group of the PGA segment and the amino group in DOX. Furthermore, the intermolecular hydrophobic interaction promoted the formation of NP/DOX with a PEG shell. The DLC and DLE of NP/DOX were 11.9 and 47.6 wt%, respectively.

CaNP/DOX was prepared by the CaCO3 mineralization of the core of mPEG-b-PGA micelle. The negatively charged PGA segment was in favor of Ca-mineralization because of the electrostatic interaction between Ca2+ and anionic GA moiety [28]. Then CO32− was added to induce multilayer ionic supersaturating around PGA segment, triggering the formation of CaCO3 mineral by accumulation of mineralized species [21]. The PEG segment served as a hydrophilic shell to enhance colloidal stability and protect the hydrophobic drug during the blood circulation. For the ideal formation of Ca-mineralized mPEG-b-PGA nanoparticle, the molar ratio of Glu−:Ca2+:CO32− was controlled to be 3:1:1, and in this case, the uncontrolled formation of CaCO3 mineral could be prevented. Then, DOX, a widely used antineoplastic agent, was loaded into the core of CaNP/DOX. The DLC and DLE of CaNP/DOX were 14.6 and 52.3 wt%, respectively, which were slightly higher compared with that of NP/DOX due to the mineralization of CaCO3. Subsequently, 3.0 mg CaNP/DOX was dissolved in 10.0 mL deionized water, the Ca2+ concentration in CaNP/DOX was 6.16 ppm by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assay (ICP-MS, Xseries II, Thermo Scientific, USA). Thus, the proportion of calcium in CaNP/DOX was 2.05 wt %, which proved the successful preparation of Ca-mineralized nanoparticle.

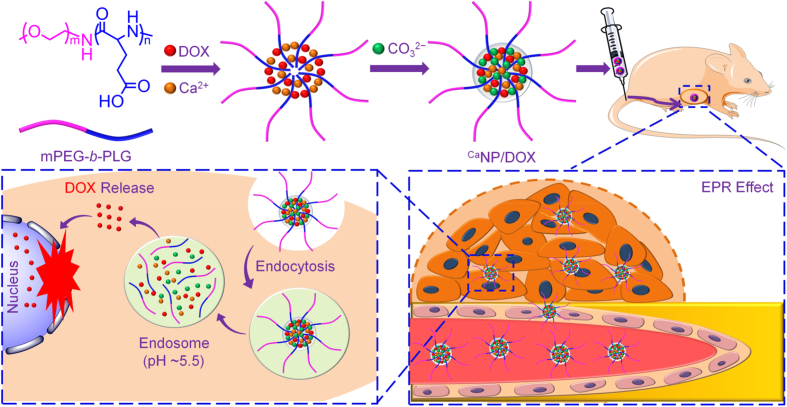

The morphologies of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX were studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Both NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX were spherical, with average diameters of 124.4 ± 7.9 and 150.3 ± 8.6 nm, respectively (Fig. 1A − B). The mean hydrodynamic radii (Rhs) of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX were detected to be 80.1 ± 4.4 and 103.0 ± 7.5 nm in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by dynamic light scattering (DLS), respectively (Fig. 1C). CaNP/DOX had a larger size than NP/DOX because of the presence of CaCO3 mineral in CaNP/DOX.

Fig. 1.

Solution properties of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX. (A, B) Typical TEM microimages of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX. (C) Rhs of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX. (D) Time- and pH-dependent DOX release behaviors of CaNP/DOX in PBS at pH 5.5, 6.8, and 7.4, 37 °C.

3.2. In vitro release of CaNP/DOX

The in vitro drug release behaviors of CaNP/DOX were evaluated in PBS of pH 7.4 (physiologic conditions), pH 6.8 (intratumoral microenvironment), and pH 5.5 (intracellular microenvironment). As shown in Fig. 1D, CaNP/DOX released only 24.1% of loaded DOX at pH 7.4 after 72 h. On the contrary, 76.2% and 47.2% of DOX were released from CaNP/DOX at pH 5.5 and 6.8, respectively, which is related to the decomposition of CaCO3 mineral in acidic conditions. This pH-triggered CaNP/DOX platform was demonstrated promising application for clinical osteosarcoma chemotherapy.

3.3. In vitro cell internalization and proliferation inhibition

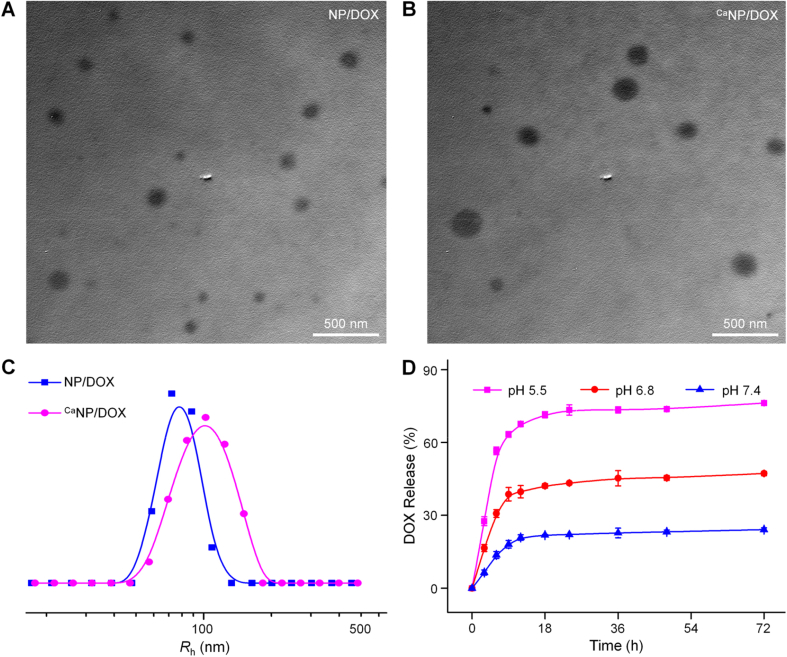

Cell uptake of DOX-loaded nanoparticles was a prerequisite for intracellular DOX delivery. The FITC-labeled nanoparticle (NP-FITC) was used to observe the internalization of NP-FITC/DOX, CaNP-FITC/DOX, and free DOX by FCM and CLSM against K7 cells.

FCM was utilized to measure the cell uptake through the semi-quantitative calculation of relative geometrical mean fluorescence intensity (GMFI) [29,30]. Fig. 2A − B showed cell internalization of various DOX formulations at different times, and the DOX concentration was set at 10.0 μg mL−1. After 2 h, the DOX uptake was highest in the free DOX group compared with the other two groups. The higher cell uptake of free DOX was achieved via a diffusion approach. Cell endocytosis induced the cell uptake of nanoparticles in a short-term incubation, which was related to the sizes. At 6 h, the intracellular accumulation of DOX in the NP-FITC/DOX and CaNP-FITC/DOX groups gradually increased. This result indicated that more drug-loaded nanoparticles released DOX with increased time. The order of cell uptake of DOX at 12 h was changed to CaNP-FITC/DOX > NP-FITC/DOX > free DOX, which should be attributed to intracellular acidity-responsive DOX release by the mineralization of CaCO3. The FITC fluorescence intensity of drug-loaded nanoparticles was also assayed by FCM (Fig. 2C − D). The uptake of NP-FITC/DOX was superior to CaNP-FITC/DOX at 2 h because the diameter of NP-FITC/DOX was smaller than that of CaNP-FITC/DOX, which promoted the cell endocytosis of NP-FITC/DOX. With the prolongation of time, the cell uptake of CaNP-FITC/DOX was gradually increased while NP-FITC/DOX did not show significant uptake at 6 h. Interestingly, the uptake of CaNP-FITC/DOX was higher than NP-FITC/DOX at 12 h. The results indicated that CaNP-FITC/DOX exhibited superiority for cell uptake in a long-term incubation, which should be attributed to intracellular acidity-responsive sustained DOX release by the mineralization of CaCO3.

Fig. 2.

Cell uptake and cytotoxicity.(A,C) FCM profiles of (A) DOX and (C) NP-FITC fluorescence intensity toward K7 cells incubated with PBS, free DOX, NP-FITC/DOX, or CaNP-FITC/DOX. (B,D) The Relative GMFIs for (B) DOX and (D) NP-FITC. (E) In vitro inhibition efficacies and (F) IC50s of free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX against K7 cells after incubation for 48 h at pH 7.4. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

For the CLSM assay, three DOX formulations were incubated with K7 cells to evaluate the intracellular release of DOX. After fixed time incubation, the K7 cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). CLSM observed the fluorescent images of cells with visualized red fluorescence of released DOX, and the results were consistent with those of FCM, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

After 2 h co-incubation, the DOX was found to accumulate in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Compared with free DOX and NP-FITC/DOX, CaNP-FITC/DOX showed weaker red fluorescence in the nucleus (Fig. S2A, Supplementary data). The results should be attributed to the slow DOX release from CaNP-FITC/DOX compared with the non-mineralized one. With the extension of time, the sustained DOX release from NP-FITC/DOX and CaNP-FITC/DOX was confirmed by the enhanced DOX fluorescence intensity at 6 h (Fig. S2B, Supplementary data). However, for a long-term incubation period, e.g., 12 h, much more DOX had been released from CaNP-FITC/DOX than that from NP-FITC/DOX into the perinucleus and nucleus regions of cells (Fig. S2C, Supplementary data). The effective cell uptake in the long-term and the intracellular selective DOX release of CaNP-FITC/DOX prompted the applications in cancer therapy.

The cytotoxicity of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX on osteosarcoma cells was evaluated in vitro by MTT assay. From Fig. 2E, NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX with DOX concentrations from 0.08 to 5.0 μg mL−1 exhibited obvious inhibition efficacy toward the proliferation of K7 cells compared to free DOX at 48 h. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) can be precisely calculated as a quantitative index of inhibition efficacy [31]. The IC50 of free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX were 0.25, 0.17, and 0.15 μg mL−1 after 48 h of incubation, respectively (Fig. 2F). Compared with NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX, the minimum proliferation inhibition of free DOX was attributed to the quick effluxion of free DOX from osteosarcoma cells. Compared with NP/DOX, the significantly pH-responsive DOX release endowed CaNP/DOX with obviously decreased IC50.

3.4. In vivo pharmacokinetics and biodistribution

The plasma pharmacokinetic curves of free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX were assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). From Fig. 3A, the disappearance of three DOX formulations in blood circulation displayed in a double exponential manner. After i.v. injection, the DOX concentration of the three groups in the plasma gradually decreased. To be specific, the maximum concentrations (Cmax) of the free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX groups were 5.0, 7.5, and 10.2 mg mL−1, separately. By calculating the proportion from 0 to the end time (AUC0-t) in concentration-time curve, the result showed that free DOX (4.4 h mg mL−1) < NP/DOX (12.1 h mg mL)−1) < CaNP/DOX (26.6 h mg mL−1). In the CaNP/DOX group, the slowest decrease of DOX level in the blood and a significant increase in systemic circulation time compared to those of the other two groups were observed, which is likely because the mineralization of CaCO3 increased the stability of the nanoparticles and inhibited DOX leakage during in vivo circulation.

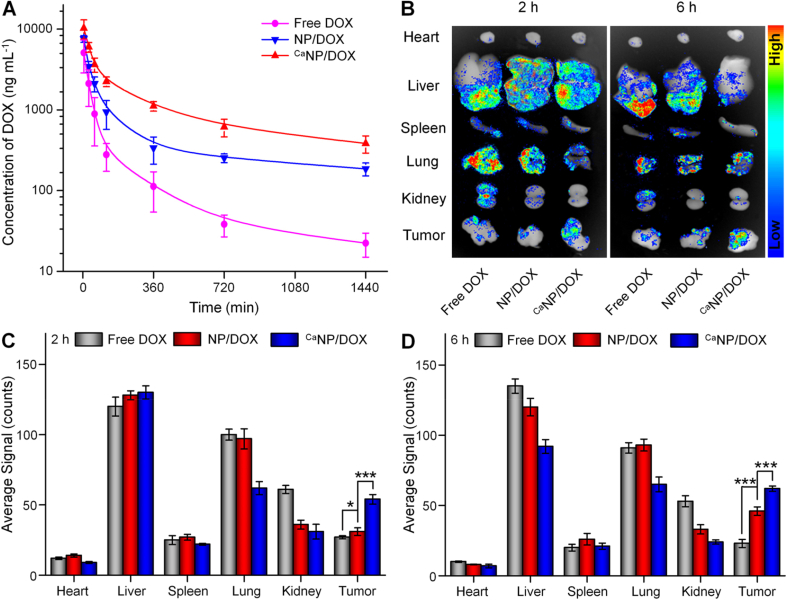

Fig. 3.

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of DOX formulations in vivo. (A) In vivo DOX pharmacokinetics after i.v. injection of free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX in to Sprague-Dawley rat. (B) DOX fluorescent images representing tissue distribution of DOX. (C, D) Average semiquantitative signals of major organs and tumor after i.v. injection to K7 osteosarcoma-allografted BALB/c mouse for (C) 2 or (D) 6 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

The ex vivo biodistribution was investigated to further assess the drug efficacy and side effects of DOX-loaded nanoparticles. Fig. 3B showed a fluorescent image of ex vivo osteosarcoma and major organs at 2 and 6 h after i.v. injection of different DOX formulations. As shown in Fig. 3C − D, the average signals of organs and tumors were semi-quantitatively analyzed. After i.v. injection 2 h, the free DOX showed considerable fluorescence signals in the liver and lung, demonstrating that it was mostly caught and metabolized in these two organs. CaNP/DOX exhibited the lowest DOX fluorescence signal in the lung and kidney, and highest signal in the tumor. The results were related to the enhanced permeability and retention effect of CaNP/DOX, as well as the pH-triggered DOX release at the intratumoral microenvironment. With the prolongation of treatment time to 6 h, DOX fluorescence signals in the tumor of free DOX group reduced to a minimum. However, the intratumoral DOX fluorescence signals in the CaNP/DOX group rose to a maximum, benefitting from the contribution of CaCO3 mineralization.

3.5. In vivo antitumor efficacy and security

The antitumor efficacy was investigated on the K7 osteosarcoma-allografted model. When the size of osteosarcoma was about 50 mm3, the mice were treated with free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX at the 5.0 mg (kg BW)−1 equivalent DOX dose. Then the control group was given the equal volume of PBS. The tumor volume and weight were accurately measured at the fixed time interval.

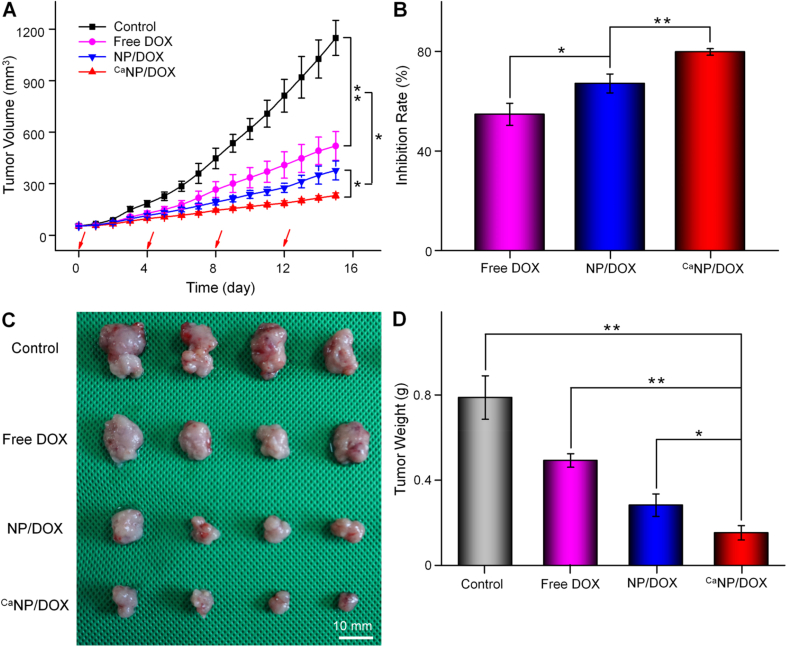

From Fig. 4A, tumor volume of the PBS group grew faster than that in the other groups, was about 1148.4 ± 102.1 mm3 when the experiment was completed. The progression of osteosarcoma was blocked in all groups except for the control one. The order of antitumor efficacy was CaNP/DOX > NP/DOX > free DOX. The tumor suppression rate of free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX after all treatments were 54.7%, 67.1%, and 79.8%, respectively (Fig. 4B). CaNP/DOX exhibited the greatest antitumor efficacy attributed to the selective DOX release and suitable particle size. The images and weights of tumors were shown in Fig. 4C − D, which visually and quantitatively confirmed the antitumor efficacy. The CaNP/DOX group had the strongest inhibitory effect on tumor growth, resulting from excellent selective DOX release in the intratumoral acidic microenvironment.

Fig. 4.

Tumor inhibition in vivo. (A) Tumor volume and (B) tumor inhibition rate of K7 osteosarcoma-allografted mouse after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). (C) Photos and (D) tumor weights of excised tumors after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX at 15 days post-treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

To evaluate the toxicity caused by DOX, the weight losses in all treatment groups were investigated. From Supplementary Fig. S3, the mouse lost 26% weight within 16 days after the i.v. injection of free DOX. However, the loss of body weight in the other groups was not noticeable. The slight weight loss of the NP/DOX, CaNP/DOX, and control groups may be attributed to the satisfied tumor-derived disturbed appetite [32]. Therefore, CaNP/DOX exhibited effective tumor growth inhibition and low systemic toxicity, indicating that it was a potential preparation for osteosarcoma therapy.

To adequately detect the safety of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX in osteosarcoma treatment, pathological analysis of mouse hearts at the end of the study was performed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, myocardial fiber rupture, edema, and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes occurred after the injection of free DOX. Myocardial damage was reduced after the injection of NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX. However, the cardiac tissue lesions in the CaNP/DOX group were the lightest compared to the other groups, which indicated that CaNP/DOX exhibited significantly decreased DOX-induced toxicity to healthy tissue and could provide a safe clinical osteosarcoma treatment.

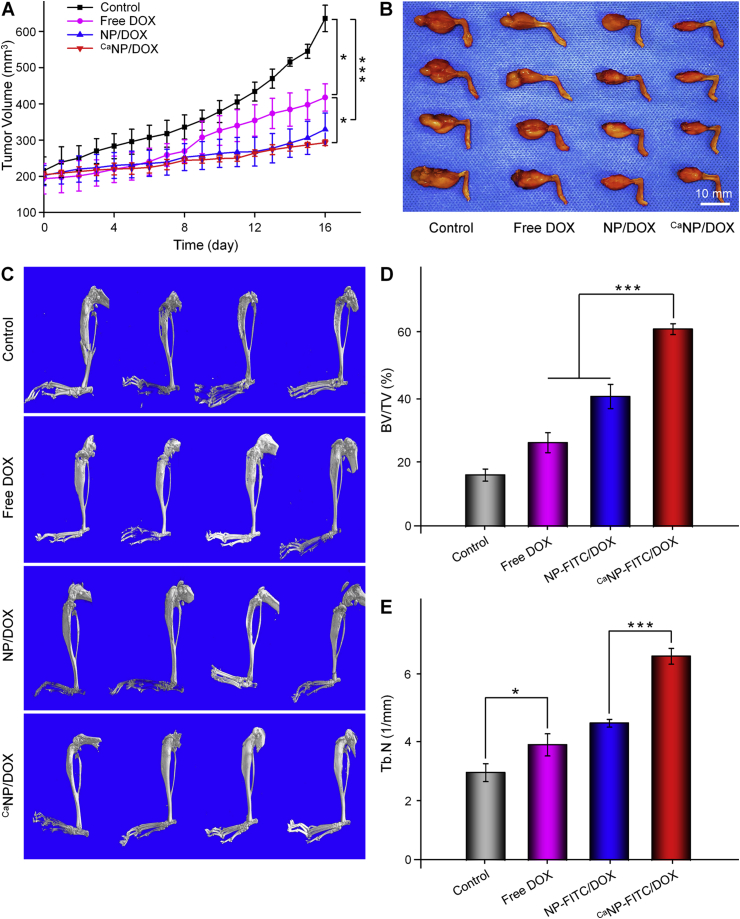

In vivo antitumor efficacies of various DOX formulations were then investigated on the 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mouse model. Compared with the other groups, the CaNP/DOX group showed the best antitumor efficacy. After sacrifice, the tumor region volumes of NP/DOX, free DOX, and control were 329.7 ± 44.7, 417.5 ± 37.7, and 635.7 ± 36.5 mm3, respectively (Fig. 5A). However, the tumor region volume of CaNP/DOX group was 292.6 ± 7.8 mm3, which was significantly smaller than that in the other three groups (Fig. 5B). The mouse tibiofibular osteosarcoma was removed and analyzed by micro-CT scan and 3D reconstruction. As shown in Fig. 5C, the 3D reconstructed images showed that the proximal tibia and distal femur of the control group had the most apparent bone destruction. However, in the CaNP/DOX group, mild bone destruction was observed, indicating that CaNP/DOX could significantly reduce bone destruction of osteosarcoma comparing with the other groups. The site of bone destruction in the 3D reconstructed image was considered to be the regions of interest (ROIs), and CTAn software is used to analyze the bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) and the trabecular number (Tb. N) (Fig. 5D − E). For BV/TV, the CaNP/DOX group was about 3.80, 2.34, and 1.51 times higher than that in control, free DOX, and NP/DOX groups, respectively. The Tb. N in the CaNP/DOX group was highest in all groups, indicating the its tremendous potential in inhibition of bone destruction.

Fig. 5.

In vivo antitumor effect and anti-bone destruction effect against 143B osteosarcoma-bearing BALB/c mouse model. (A) Tumor region volumes and (B) photos of tibial primary osteosarcoma tumors. (C) 3D reconstructed image of tibia performed using micro-CT of 143B osteosarcoma-bearing BALB/c mouse after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX. (D) Bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) and (E) trabecular number (Tb. N) in the regions of interest (ROI) of mouse. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

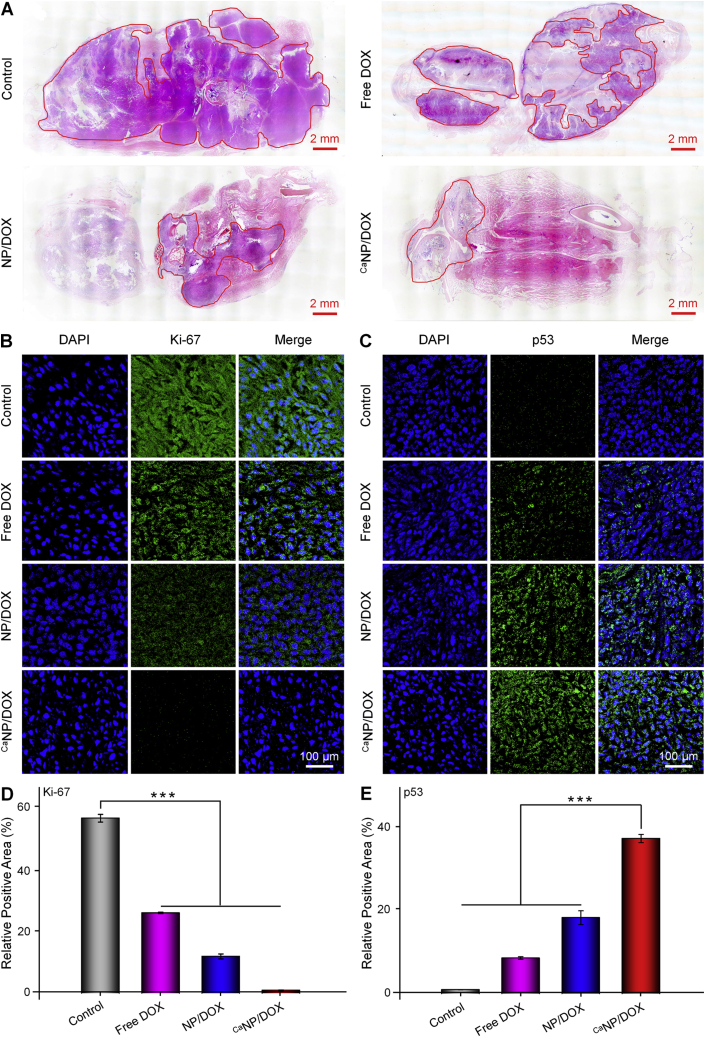

To further investigate the antitumor effect, the tibiofibular osteosarcoma of mouse was removed for decalcification. Decalcification was complete when the needle passes easily through the bone and then sectioned for histopathological and immunofluorometric analysis. As shown by the H&E staining image (Fig. 6A), the area circled by the red line was the detected tumor tissue. The tumor infiltration area of CaNP/DOX group was significantly smaller than the other groups. Ki-67 and p53 were detected by immunohistochemistry to assess the proliferation and apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells, respectively. The expression of Ki-67 was minimal in the CaNP/DOX group, indicating the osteosarcoma grew slowest after treatment (Fig. 6B). The appearance of p53 represents cell death or perpetual suppression of cell growth [33]. The CaNP/DOX group had the most vigorous fluorescence intensity of p53, which indicated that CaNP/DOX caused the most severe apoptosis in the tissue of osteosarcoma (Fig. 6C). Then the immunofluorescent images were semi-quantitatively analyzed, and the signal of Ki-67 in the control group were 2.17, 4.76, and 16.65 times of those of the free DOX, NP/DOX, and CaNP/DOX groups, respectively (Fig. 6D). Moreover, the signal of p53 in the CaNP/DOX group was 4.34 times higher than that of the free DOX group (Fig. 6E). According to the above data, it can be proved that CaNP/DOX exhibited more effective treatment of osteosarcoma.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of tumor growth toward 143B osteosarcoma-bearing BALB/c mouse model. (A) Histopathological (H&E) analysis of tumor from 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mouse after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX. (B, C) Immunofluorometric analysis (Ki-67, p53) of tumor sections from 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mouse after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX. (D, E) Relative Ki-67 and p53 positive areas of tumor sections. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

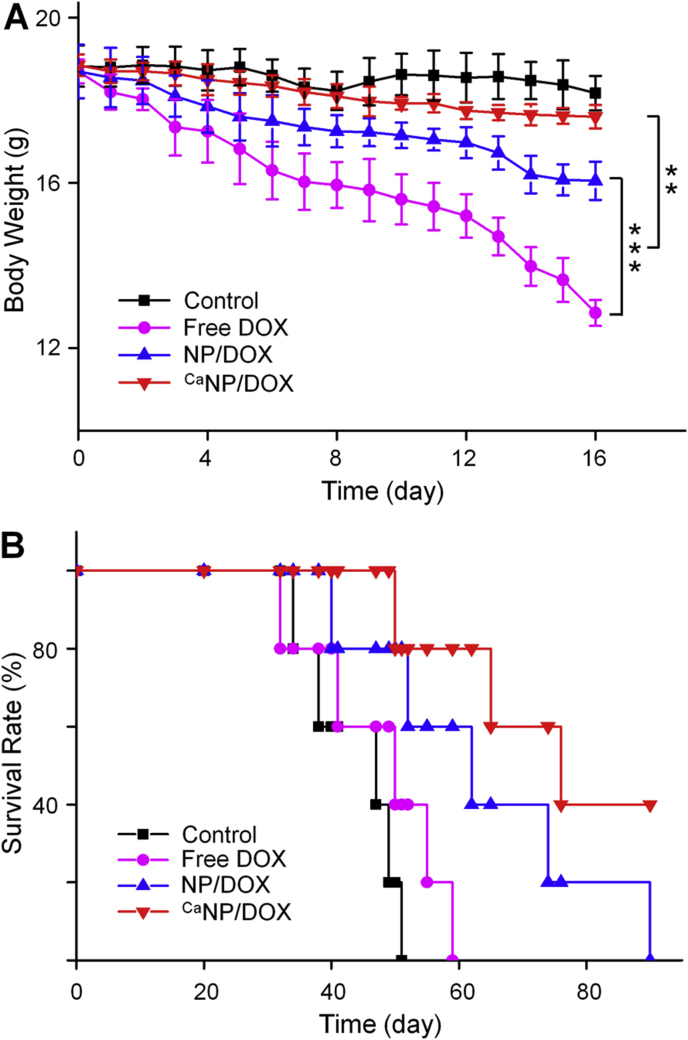

Moreover, to further investigate the in vivo safety, the body weight of 143B osteosarcoma-bearing mouse was also monitored during treatment (Fig. 7A). The phenomenon of weight loss occurred in all tumor-bearing mouse during treatment. Mice in the CaNP/DOX and control groups lost only 6.6% and 3.5% of their body weight over time. However, free DOX and NP/DOX exhibited 31.3% and 14.2% weight loss. Free DOX brought severe weight decline because of the adverse reaction. The weight loss after PBS treatment was associated with tumor-induced cachexia. The survival rate of each group of mouse was shown in Fig. 7B. Mice injected with NP/DOX and CaNP/DOX revealed a significantly prolonged survival term, especially for CaNP/DOX. This result indicated that CaNP/DOX showed excellent performance in reducing systematic toxicity.

Fig. 7.

In vivo safety. (A) Body weights and (B) survival rates of 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mice after treatment with PBS, free DOX, NP/DOX, or CaNP/DOX. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

In summary, CaNP/DOX exhibited satisfactory antitumor efficacy and a negligible side effect. All the results indicated that CaNP/DOX is an excellent potential candidate for osteosarcoma treatment.

4. Conclusion

A Ca-mineralized DOX-loaded polypeptide nanoparticle (CaNP/DOX) was successfully developed for osteosarcoma chemotherapy. Relative to free DOX and NP/DOX, CaNP/DOX platform could enhance tumor accumulation, implement intracellular selective drug release, upregulate antitumor activity, and improve safety to K7 osteosarcoma-allografted and 143B orthotopic osteosarcoma mouse model. Therefore, with efficient drug loading, enhanced tumor accumulation, and reduced side effect, CaNP/DOX offers a potential antitumor drug delivery platform for osteosarcoma therapy.

Credit author statement

The authors declare that this manuscript has not been published previously, and that it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All the authors have confirmed the submission of this manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ke Li: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Di Li: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Li Zhao: Validation, Writing - review & editing. Yonghe Chang: Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft. Yi Zhang: Methodology, Data curation. Yan Cui: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Zhiyu Zhang: Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51803006), the Scientific Development Program of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 20170541058), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2019M650297).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.04.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mura S., Nicolas J., Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat. Mater. 2013;12(11):991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai Y., Xu C., Sun X., Chen X. Nanoparticle design strategies for enhanced anticancer therapy by exploiting the tumour microenvironment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46(12):3830–3852. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00592f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang Z., Liu Y., Feng X., Ding J. Functional polypeptide nanogels. J. Funct. Polym. 2019;32(1):13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y., Wang F., Li M., Yu Z., Qi R., Ding J., Zhang Z., Chen X.J.A.S. Self-stabilized hyaluronate nanogel for intracellular codelivery of doxorubicin and cisplatin to osteosarcoma. Adv. Sci. 2018;5(5):1700821. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanamala M., Wilson W.R., Yang M.M., Palmer B.D., Wu Z.M. Mechanisms and biomaterials in pH-responsive tumour targeted drug delivery: A review. Biomaterials. 2016;85:152–167. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun T.M., Wang Y.C., Wang F., Du J.Z., Mao C.Q., Sun C.Y., Tang R.Z., Liu Y., Zhu J., Zhu Y.H., Yang X.Z., Wang J. Cancer stem cell therapy using doxorubicin conjugated to gold nanoparticles via hydrazone bonds. Biomaterials. 2014;35(2):836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang C.Y., Yang Y.Q., Huang T.X., Zhao B., Guo X.D., Wang J.F., Zhang L.J. Self-assembled pH-responsive mPEG-b-(PLA-co-PAE) block copolymer micelles for anticancer drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33(26):6273–6283. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H., Zhu L., Torchilin V.P. pH-sensitive poly(histidine)-PEG/DSPE-PEG co-polymer micelles for cytosolic drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2013;34(4):1213–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang H.C., Bae Y.H. Co-delivery of small interfering RNA and plasmid DNA using a polymeric vector incorporating endosomolytic oligomeric sulfonamide. Biomaterials. 2011;32(21):4914–4924. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj I., Singhal R. Poly(glutamic acid) – an emerging biopolymer of commercial interest. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102(10):5551–5561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X., Liu P., Song Q., Gong N., Yang L., Wu W.D. Surface charge-reversible polyelectrolyte complex nanoparticles for hepatoma-targeting delivery of doxorubicin. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3(30):6185–6193. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00600g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H.K., Van den Bossche J., Hyun S.H., Thompson D.H. Acid-triggered release via dePEGylation of fusogenic liposomes mediated by heterobifunctional phenyl-substituted vinyl ethers with tunable pH-sensitivity. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23(10):2071–2077. doi: 10.1021/bc300266y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C., Wang G.T., Wang Z.Q., Zhang X. A pH-responsive superamphiphile based on dynamic covalent bonds. Chem. Eur J. 2011;17(12):3322–3325. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng H.Z., Liu J.J., Zhao X.F., Zhang Y.M., Liu J.F., Xu S.X., Deng L.D., Dong A.J., Zhang J.H. PEG-b-PCL copolymer micelles with the ability of pH-controlled negative-to-positive charge reversal for intracellular delivery of doxorubicin. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(11):4281–4292. doi: 10.1021/bm501290t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu C., Zhu L., Qiu F., Wang D., Su Y., Zhu X., Yan D. Facile PEGylation of Boltorn® H40 for pH-responsive drug carriers. Polymer. 2013;54(8):2020–2027. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittella F., Miyata K., Maeda Y., Suma T., Watanabe S., Chen Q., Christie R.J., Osada K., Nishiyama N., Kataoka K. Pancreatic cancer therapy by systemic administration of VEGF siRNA contained in calcium phosphate/charge-conversional polymer hybrid nanoparticles. J. Controlled Release. 2012;161(3):868–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong Z., Feng L., Zhu W., Sun X., Gao M., Zhao H., Chao Y., Liu Z. CaCO3 nanoparticles as an ultra-sensitive tumor-pH-responsive nanoplatform enabling real-time drug release monitoring and cancer combination therapy. Biomaterials. 2016;110:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu L.D., Chen Y., Lin H., Du W.X., Chen H.G., Shi J.L. Ultrasmall mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles: morphology modulations and redox-responsive biodegradability for tumor-specific drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2018;161:292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao K.R., Cong X.X., Feng L.Z., Chen H.M., Wang J.L., Wu C.X., Liu K., Xiao C.S., Yang Y.G., Sun T.M. Intratumoral delivery of M-CSF by calcium crosslinked polymer micelles enhances cancer immunotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7(7):2769–2776. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00226j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Y., Qiao H.Z., Su Z.G., Chen M.L., Ping Q.N., Sun M.J. PEGylated carboxymethyl chitosan/calcium phosphate hybrid anionic nanoparticles mediated hTERT siRNA delivery for anticancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35(27):7978–7991. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., Cai L., Li D., Lao Y.-H., Liu D., Li M., Ding J., Chen X. Tumor microenvironment-responsive hyaluronate-calcium carbonate hybrid nanoparticle enables effective chemotherapy for primary and advanced osteosarcomas. Nano Res. 2018;11(9):4806–4822. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parakhonskiy B.V., Haase A., Antolini R. Sub-micrometer vaterite containers: synthesis, substance loading, and release. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51(5):1195–1197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Som A., Raliya R., Tian L., Akers W., Ippolito J.E., Singamaneni S., Biswas P., Achilefu S. Monodispersed calcium carbonate nanoparticles modulate local pH and inhibit tumor growth in vivo. Nanoscale. 2016;8(25):12639–12647. doi: 10.1039/c5nr06162h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu C.Y., Yan Y.F., Tan J.C., Yang D.H., Jia X.J., Wang L., Xu Y.S., Cao S., Sun S.T. Biodegradable nanoparticles of polyacrylic acid-stabilized amorphous CaCO3 for tunable pH-responsive drug delivery and enhanced tumor inhibition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29(24) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding J., Zhuang X., Xiao C., Cheng Y., Zhao L., He C., Tang Z., Chen X. Preparation of photo-cross-linked pH-responsive polypeptide nanogels as potential carriers for controlled drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21(30):11383–11391. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding J.X., Xu W.G., Zhang Y., Sun D.K., Xiao C.S., Liu D.H., Zhu X.J., Chen X.S. Self-reinforced endocytoses of smart polypeptide nanogels for “on-demand” drug delivery. J. Controlled Release. 2013;172(2):444–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min K.H., Min H.S., Lee H.J., Park D.J., Yhee J.Y., Kim K., Kwon I.C., Jeong S.Y., Silvestre O.F., Chen X., Hwang Y.S., Kim E.C., Lee S.C. pH-controlled gas-generating mineralized nanoparticles: a theranostic agent for ultrasound imaging and therapy of cancers. ACS Nano. 2015;9(1):134–145. doi: 10.1021/nn506210a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Z.L., Feng L.Z., Zhu W.W., Sun X.Q., Gao M., Zhao H., Chao Y., Liu Z. CaCO3 nanoparticles as an ultra-sensitive tumor-pH-responsive nanoplatform enabling real-time drug release monitoring and cancer combination therapy. Biomaterials. 2016;110:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng X.R., Ding J.X., Gref R., Chen X.S. Poly(β-cyclodextrin)-mediated polylactide-cholesterol stereocomplex micelles for controlled drug delivery. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017;35(6):693–699. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun C.Y., Zhang B.B., Zhou J.Y. Light-activated drug release from a hyaluronic acid targeted nanoconjugate for cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2019;7(31):4843–4853. doi: 10.1039/c9tb01115c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding J., Li C., Zhang Y., Xu W., Wang J., Chen X. Chirality-mediated polypeptide micelles for regulated drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2015;11:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnen H., Lin S., Kuffner T., Brown D.A., Tsai V.W.W., Bauskin A.R., Wu L., Pankhurst G., Jiang L., Junankar S., Hunter M., Fairlie W.D., Lee N.J., Enriquez R.F., Baldock P.A., Corey E., Apple F.S., Murakami M.M., Lin E.J., Wang C., During M.J., Sainsbury A., Herzog H., Breit S.N. Tumor-induced anorexia and weight loss are mediated by the TGF-β superfamily cytokine MIC-1. Nat. Med. 2007;13(11):1333–1340. doi: 10.1038/nm1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flore K., Labuschagne C.F., Vousden K.H. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16(7):393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrm4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.