Abstract

COVID-19 disproportionately affects the poor and vulnerable. Community health workers are poised to play a pivotal role in fighting the pandemic, especially in countries with less resilient health systems. Drawing from practitioner expertise across four WHO regions, this article outlines the targeted actions needed at different stages of the pandemic to achieve the following goals: (1) PROTECT healthcare workers, (2) INTERRUPT the virus, (3) MAINTAIN existing healthcare services while surging their capacity, and (4) SHIELD the most vulnerable from socioeconomic shocks. While decisive action must be taken now to blunt the impact of the pandemic in countries likely to be hit the hardest, many of the investments in the supply chain, compensation, dedicated supervision, continuous training and performance management necessary for rapid community response in a pandemic are the same as those required to achieve universal healthcare and prevent the next epidemic.

Keywords: health systems, health policy, public health

Summary box.

Community health workers (CHWs) are poised to play a pivotal role in fighting the pandemic, especially in low-income countries with vulnerable health systems.

The COVID-19 response must build on existing platforms, infrastructure and relationships wherever possible; the focus should be on supporting the Ministries of Health and regional authorities as they lead coordinated responses.

Immediate investment in community health systems will help achieve the following goals: PROTECT healthcare workers, INTERRUPT the virus, MAINTAIN existing healthcare services while surging their capacity, and SHIELD the most vulnerable from socioeconomic shocks.

Achieving these goals will require targeted actions at different stages of the pandemic. These actions are delineated in the article.

Many of the investments in the supply chain, compensation, dedicated supervision, continuous training and performance management necessary for rapid community response in a pandemic are the same as those required to achieve universal health care and prevent the next epidemic.

Introduction

Over 823 626 cases of COVID-19 have been reported worldwide as of 1 April 2020, including cases in over 75 low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 COVID-19 disproportionately affects the poor and vulnerable2: sharp increases in COVID-19 case loads will overwhelm health systems in countries already facing shortages of health workers and supplies. With millions of lives at stake, decisive action must be taken now to blunt the impact of the pandemic in countries likely to be hit the hardest.3

Investment is needed at all levels of the health system, and community health workers (CHWs) are poised to play a pivotal role in fighting the pandemic, especially in low-income countries with vulnerable health systems. CHWs that are equipped, trained and supported as part of a well-functioning health system can help keep the pandemic in check.

The Community Health Impact Coalition (CHIC)4 is a network of health practitioners working in over 30 countries that exists to accelerate the uptake of high-impact community health systems design. Its members have developed and supported high-quality community health programmes with governments and communities across the globe, through multiple outbreaks and epidemics.

Given that in a pandemic speed is of the essence, this paper was generated in less than 72 hours using an adapted nominal group technique (NGT). NGT is an organisational planning technique5 that involves four phases: (1) nominal/silent phase: participants individually write their responses to a defined question without discussion; (2) item generation phase: participants take turns sharing their responses, and each response is recorded as a succinct idea without being discussed; (3) discussion/clarification phase: participants ask clarifying questions and delineate the pros/cons of each idea; and (4) voting phase: participants assign ranks to the items. This approach was chosen as it is comprehensive, quick and of low cost.6 It was adapted in the following ways: given that participants were distributed across multiple continents and 12 time zones, phases 1 and 2 took place entirely asynchronously—responses were collected on a shared drive. The discussion phase took place over a 24-hour period, first asynchronously (participants asked and answered questions in a shared word processing document) and subsequently in a video meeting. The final voting phase took place during an additional video meeting. Selection of participants was opportunistic: any health practitioner from the CHIC network was invited to participate.

This paper is intended to advocate for rapid action in response to the evolving COVID-19 pandemic, providing an initial modifiable roadmap to funders, non-governmental organisations and Ministries of Health alike.

Priorities

The COVID-19 response must build on existing platforms, infrastructure and relationships wherever possible. Maximum leverage and minimum duplication will allow greater short-term success and long-term sustainability.

Our primary focus is supporting the Ministries of Health and regional authorities as they lead coordinated responses. This means integrating all front-line health workers, including CHWs, in the design and implementation of the response.

Immediate investment in community health systems will help achieve the following goals:

PROTECT healthcare workers.

INTERRUPT the virus.

MAINTAIN existing healthcare services while surging their capacity.

SHIELD the most vulnerable from socioeconomic shocks.

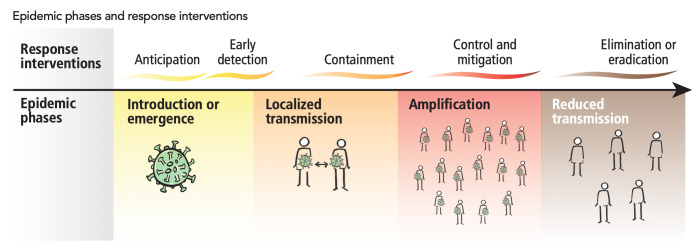

Achieving these goals will require targeted actions at different stages of the pandemic (table 1, figure 1).

Table 1.

What’s needed now and next by epidemic phases

| Now | Next |

| Anticipation/early detection/containment | Control/elimination |

| PROTECT health workers. | |

|

|

| INTERRUPT the virus. | |

|

|

| MAINTAIN health services while surging their capacity. | |

|

|

| SHIELD the vulnerable. | |

|

|

CHW, community health workers; LMICs, low-income and middle-income countries; PPE, personal protective equipment; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

Figure 1.

Epidemic phases and response interventions.24

PROTECT healthcare workers

Professionalised, proactive CHWs are particularly well placed to build on the foundations of trust they have already established, and to communicate and implement new and rapidly evolving community-level response measures. But to do this, they must be protected.

In Lombardy, Italy, the infection rate is 12 times higher for health workers than for the general population.7 In India, CHWs—the vast majority of whom are women—are conducting contact tracing with neither masks nor hand sanitiser.8 When health workers contract COVID-19, it not only depletes morale, it also depletes our ability to fight the virus.

The need to protect front-line health workers is particularly relevant in places with the worst health workforce shortages: Africa has 3% of the world’s health workforce but nearly a quarter of the world’s burden of disease.9 These shortages are even more pronounced in rural areas, which makes protecting CHWs not only a moral obligation but a strategic one as well.

Global shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) risk exacerbating existing inequalities, with high-income countries stockpiling supplies and hoarding global manufacturing capacity at the expense of others. CHWs must be included in COVID-19 PPE quantification estimates.

Now

Coordinate with partners and invest to rapidly produce, deploy and restock PPE. The WHO’s COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund is working to ensure front-line health workers can keep safe and keep serving. Responsive logistics systems already used for sample transport and last mile medicines distribution can track and deliver PPE to the community level, if supplies are adequate and communication systems exist to quickly identify gaps.

Ensure CHWs are included in PPE projections. Not all estimates take CHWs into account; corrective investment will likely be required. Data on CHW numbers, services and distribution exist to inform these plans.

Next

Work with governments to pay CHWs for supplemental hours. This is particularly relevant for part-time or currently unpaid CHWs and those without guaranteed paid sick leave. Where it is deemed feasible, equitable and preferable by CHWs, mobile payments can be used. Given the risk posed by COVID-19 to CHWs and the disruption of their workflows, money currently earmarked for performance-based incentives should be reallocated to cover routine salaries or stipends for all active health workers (box 1).

Box 1. PROTECT: tracking impact.

Percentage of personal protective equipment supply needs met.

Number of health workers infected.

Percentage of community health workers’ salaries or stipends paid on time.

INTERRUPT the virus

Despite the suggestions of some world leaders, the virus cannot be ‘left to run its course’. This approach would be a death sentence for millions of vulnerable people.10 We must, instead, rapidly scale up testing, bringing it as close as possible to people’s homes. As doctors in Italy have recently noted, an epidemic requires a change from hospital-centred towards community-centred care.11 Supporting CHWs to lead widespread testing, contact tracing, isolation and quarantine will be key to slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Two diagnostic tests currently exist. The current, WHO-approved testing method is polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which detects the genetic code of the novel coronavirus through a nasal swab, oral swab or sputum. It requires advanced laboratory capability that often does not exist in countries with limited preparedness and response resources. An emerging alternative option is the rapid diagnostic test (RDT), which returns results in 15 minutes and can be conducted in the field.12

While RDTs are simpler than PCR, the tests do not deliver or conduct themselves. Healthcare teams must be rapidly expanded, equipped and trained to deliver preventive, diagnostic and management services for COVID-19 (table 2).

Table 2.

Roles of CHWs to INTERRUPT the COVID-19 epidemic25

| Prevent |

|

| Detect* |

|

| Respond |

|

*Mobilising CHWs to test, contact-trace and isolate cases is the strategy best placed to control the epidemic. In the absence of PPE and RDTs, however, CHWs should adopt an information provision strategy rather than a testing-focused strategy. Workflows should be modified to allow for the provision of patient care in a safe manner via phone or from a safe distance.

CHW, community health workers; PPE, personal protective equipment; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

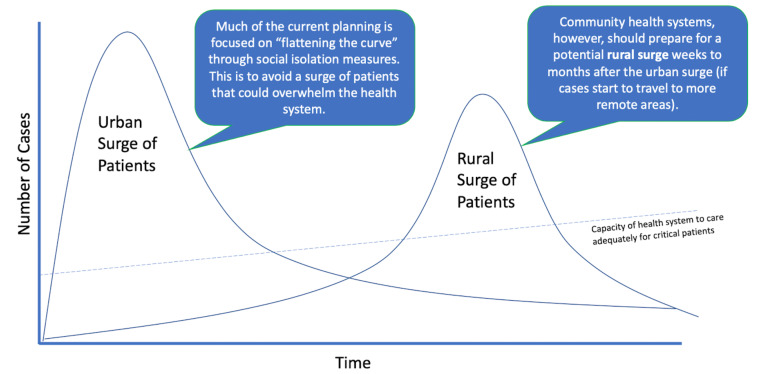

Extensive coordination is needed to mobilise private and public sector channels to distribute COVID-19 tests and supplies to highest need areas. Since supply is unlikely to meet demand, these efforts need to be informed by data-driven models that account for capacity, morbidity and mortality risk, and risk of COVID-19 spread in vulnerable areas over time (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timing of potential spread in vulnerable areas, from urban to rural.

Now

Standardise and endorse a protocol for CHWs responding to COVID-19.

Engage with governments on the approach for training existing community health teams to prevent, detect and respond. This includes expanding community event-based surveillance modules to incorporate COVID-19 and using mHealth and e-learning tools to accelerate uptake and provide accreditation.13 It is imperative that CHWs demonstrate mastery of infection control skills to keep themselves safe and control the epidemic. Existing digital technologies can support training reinforcement, practice, point-of-care test procedures and clinical guidance, and remote supervision.14

Quantify demand and procure RDTs and other COVID-19 supplies (reagents, swabs). Rapidly deploy these in countries on the brink of their own epidemic. Support governments to fast-track product registration and importation approvals, as well as coordinate distribution.

Next

Continue to invest in ongoing training for community health teams. COVID-19 case definitions, protocols and social distancing policies are expected to change frequently. Consequently, CHW training on COVID-19 needs to be continuous. Consider adaptable, cost-effective ways of sharing information and updates with CHWs (text messages, mobile applications, phone trees, 24-hour support phone number) (box 2).

Box 2. INTERRUPT: tracking impact.

Number of rapid tests deployed.

Percentage of stockouts reported.

Percentage of community health workers trained to prevent, detect and respond.

Number of cases identified (suspect + confirmed/probable).

Number of cases outside established contact lists.

MAINTAIN existing health services while surging their capacity

During times of crisis, essential health services often decline, which can ultimately kill more people than the pandemic itself.15 One of the greatest dangers of a pandemic is interrupting care for other conditions by overwhelming already under-resourced health systems. For example, during the Ebola epidemic, access to healthcare services fell by half, dramatically increasing deaths from malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.16 The vulnerable bore the brunt of the pandemic: childhood immunisations were significantly reduced and, in some areas, the number of pregnant women delivering in health facilities decreased by more than 80%.16

In many countries, health workforce availability remains less than 10% of what is needed to deliver essential primary healthcare services.17 We must continue to provide and expand free, high-quality healthcare for all through investment in stronger health systems—supporting community health teams will be key to ensuring this continuity of care (box 3).18

Box 3. Roles of community health workers to MAINTAIN and surge existing services25.

Sustain routine primary healthcare services, for example, vaccinations and integrated community case management of young children with malaria, pneumonia or diarrhoea.26

Codesign workflow modifications necessary to continue primary healthcare delivery while being responsive to changing pandemic conditions and patient and health worker safety.

Introduce safe means of requesting and accessing care in the event of community-level COVID-19 spread.

Postpone non-essential services to alleviate capacity constraints on existing health workforce.20

Monitor patients for clinical deterioration and support rapid referral of individuals who require hospitalisation, reinforcing links between the health system and communities.

Harness digital technology to receive requests for care, proactively check in with families, follow up with patients, assess symptoms and establish care plans.

Support preparation of health systems and communities for the eventual introduction of still-in-development COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, including outreach to high-risk groups.29

Implement or support disinfection of high-risk surfaces in communities using appropriate infection prevention and control supplies and procedures.

Investments in the national supply chain will be required for new capabilities and surge capacity. Supply chains in many low-income countries are structured for predictable long-term demand, not rapidly changing product requirements. Many countries lack end-to-end visibility into their supply chains, especially at the rural health facility and community levels. Managing routine needs, while layering on additional demand for PPE, test kits and COVID-19 treatment and equipment, will strain even the stronger supply chains in LMICs.19

Moreover, until RDTs are available, testing logistics will require routine, scheduled sample transport networks, such as those already in place in many countries to support community-based HIV programmes. These networks must be equipped for surge capacity to top up inventory of essential supplies or shift inventory between locations, as well as meet the increased need for vehicles, motorbikes, and personnel to transport test samples.

Now

Encourage governments to designate CHWs as essential workers to avoid interruption of essential and life-saving care.

Invest in the national supply chain to quantify demand and coordinate distribution of essential commodities and surge supplies (eg, oxygen, fuel ventilators and outdoor fever tents).

Next

Optimise staffing ratios at all levels of community health system to promote continuity of care. Frequent supportive supervision may be needed, given how rapidly the pandemic and its attendant protocols, procedures and problems will evolve. CHWs facing considerable vulnerability and stress will need more support from supervisors during this period (box 4).

Box 4. MAINTAIN: tracking impact.

Number of interruptions to primary healthcare (PHC) services.

Percentage of pregnant women delivering in health facilities.

Number of assessments of children under 5.

SHIELD the most vulnerable from socioeconomic shocks

COVID-19 will disproportionately affect the poor and vulnerable, worsening prevailing inequalities.20 Strong social support is critical for effective outbreak control.21 Many low-income countries, however, will simply not have the resources to cushion the pandemic’s economic blow. CHWs can help by supporting their communities in several ways (box 5).

Box 5. Roles of community health workers to SHIELD the vulnerable25.

Support self-isolation and monitor patients in the community while ensuring delivery of food, social and medical support.

Combat misinformation, fear and mistrust by acting as a bridge to the formal health system and national authorities. Inspire positive behaviour change and collective action.

Identify and educate at-risk populations (elderly, immunocompromised, those with underlying conditions) to reduce their exposure to COVID-19.

Quarantine is a distinct challenge for many of the communities we serve, where individuals often do not have the resources to effectively self-quarantine. This includes private space for social distancing, the flexibility to stop work and potentially forgo income, and soap, water and hand sanitisers. Vulnerable communities need to be supported by trained, supervised, equipped and protected front-line providers, including CHWs, as part of an effective COVID-19 response.

Now

Support immediate cash injections at the household level and the creation of neighbourhood plans to protect the most vulnerable. Eliminate point-of-care user fees for COVID-19 testing, treatment and care where these exist.

Work with governments and funding partners to ensure that CHW budgets incorporate holistic support, including food supplementation, access to clean water, and mental health and psychosocial support.

Next

Issue a call to multilaterals, regional development banks and national governments to establish economic recovery initiatives to reinvigorate the local economy and support financial recovery for impacted households and businesses.

Invest in surveillance of emerging disease hotspots, which are more concentrated in lower-latitude developing countries. Current emerging infectious disease surveillance and investigation are poorly allocated, with the majority of the globe’s resources focused on places from where the next important emerging pathogen is least likely to originate.22 WHO should consider CHWs as part of the communicable disease surveillance response team (box 6).

Box 6. SHIELD: tracking impact.

Percentage of households receiving immediate cash injections.

Number of countries with funding secured for long-term economic recovery.

Conclusion

An effective response to COVID-19 requires strong coordination across multiple sectors, guided by strong leadership at all levels of the health system. Community-based efforts should be integrated with existing health system infrastructure and aligned with plans and protocols endorsed by the Ministries of Health and regional authorities.

Isolated investments in CHWs for COVID-19 will not work. While strategic investments at all levels of the health system are needed, there are steps we can take now to protect CHWs and communities on the front lines of this pandemic. These steps include mobilising the following:

Appropriate PPE for CHWs and front-line providers.

Rapid test kits for use outside the clinic.

Medicines and equipment for treatment at community and facility levels.

Digital tools for information sharing, communication, training, surveillance and decision support.

COVID-19 reminds us of the urgent need for strong health systems that can provide essential services while protecting against emerging pandemic threats. The investments in the supply chain, compensation, dedicated supervision, continuous training and performance management23 necessary for rapid community response in a pandemic are the same as those required to achieve universal health coverage and prevent the next epidemic. Strengthening high-quality healthcare delivery systems will save lives, not just during COVID-19, but always.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drmballard, @esbancroft, @joshnesbit, @isaacholeman, @ashlaurenrogers

Contributors: EB and MB conceptualised the project. MB drafted the work. All authors made substantial contributions to the drafting of the work, contributing various sections and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ [Accessed 25 Mar 2020].

- 2.Walton D. Coronavirus will disproportionately affect the poor & vulnerable, 2020. Available: https://medium.com/build-health-international/coronavirus-will-disproportionately-affect-the-poor-vulnerable-76606f9a9eb2

- 3.Vermund S, Collins C. Remembering America’s global connections in the time of coronavirus, 2020. Available: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/remembering-americas-global-connections-time-coronavirus

- 4.Community Health Impact Coalition Available: www.chwimpact.org

- 5.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J Appl Behav Sci 1971;7:466–92. 10.1177/002188637100700404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson F, Soanes L. The development of clinical competencies for use on a paediatric oncology nursing course using a nominal group technique. J Clin Nurs 2000;9:459–69. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A, et al. At the epicenter of the Covid-19Pandemic and humanitarian Crisesin Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Delivery 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha N. India’s first line of defense against the coronavirus is an army of 900,000 women without masks or hand sanitizer, 2020. Available: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nishitajha/india-coronavirus-cases-ashas

- 9.Maddison AR, Schlech WF. Will universal access to antiretroviral therapy ever be possible? The health care worker challenge. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2010;21:e64–9. 10.1155/2010/432306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson N, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand, 2020. Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A. At the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Delivery 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partners in Health , 2020. Available: https://www.pih.org/article/video-dr-kj-seung-explains-rapid-testing-coronavirus

- 13.Ballard M, Schwarz R. Employing practitioner expertise in optimizing community healthcare systems. Healthc 2019;7:100334. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballard M, Montgomery P. Systematic review of interventions for improving the performance of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014216. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plucinski MM, Guilavogui T, Sidikiba S, et al. Effect of the Ebola-virus-disease epidemic on malaria case management in Guinea, 2014: a cross-sectional survey of health facilities. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:1017–23. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00061-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parpia AS, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Wenzel NS, et al. Effects of response to 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak on deaths from malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis, West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:433–41. 10.3201/eid2203.150977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030, 2016. Available: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/pub_globstrathrh-2030/en/

- 18.Partners in Health PIH's emergency coronavirus response, 2020. Available: https://www.pih.org/article/pihs-emergency-coronavirus-response

- 19.World Health Organization Disease commodity package - novel Coronavirus (nCoV), 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/disease-commodity-package-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)

- 20.Dahab M, van Zandvoort K, Flasche S, et al. COVID-19 control in low-income settings and displaced populations: what can realistically be done? 2020. Available: https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres/health-humanitarian-crises-centre/news/102976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Partners in Health Dr. Paul Farmer Urges “Merciful and Humane” COVID Responses; 2020. https://www.pih.org/article/globe-op-ed-dr-paul-farmer-urges-merciful-and-humane-covid-responses

- 22.Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008;451:990–3. 10.1038/nature06536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1397–404. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30482-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Managing epidemics: key facts about major deadly diseases, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/managing-epidemics-interactive.pdf

- 25.Wiah O, Subah M, Varpilah B, et al. Prevent, detect, respond: how community health workers can help in the fight against COVID-19. BMJ Opinion 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyce M, Katz R. Community health workers and pandemic preparedness: current and prospective roles, 2020. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00062/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Medic Mobile Demo of CHT COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test APP for community health workers, 2020. You tube. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3iqlMmt3eU

- 28.de Vries DH, Rwemisisi JT, Musinguzi LK, et al. The first mile: community experience of outbreak control during an Ebola outbreak in Luwero district, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2016;16:161. 10.1186/s12889-016-2852-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization Strengthening primary health care through community health workers: investment case and financing recommendations, 2015. Available: https://www.who.int/hrh/news/2015/CHW-Financing-FINAL-July-15-2015.pdf