The biosynthesis of fungal natural products is highly regulated not only in terms of transcription and translation but also regarding the cellular localization of the biosynthetic pathway. In all eukaryotes, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in the production of organelles, which are subject to cellular traffic or secretion. Here, we show that in Fusarium verticillioides, early steps in fumonisin production take place in the ER, together with ceramide biosynthesis, which is targeted by the mycotoxin. A first level of self-protection is given by the presence of a FUM cluster-encoded ceramide synthase, Fum18, hitherto uncharacterized. In addition, the final fumonisin biosynthetic step occurs in the cytosol and is thereby spatially separate from the fungal ceramide synthases. We suggest that these strategies help the fungus to avoid self-poisoning during mycotoxin production.

KEYWORDS: Fusarium, fumonisin B1, ceramide synthase, ABC transporter, metabolite compartmentalization

ABSTRACT

Fumonisin (FB) mycotoxins produced by species of the genus Fusarium detrimentally affect human and animal health upon consumption, due to the inhibition of ceramide synthase. In the present work, we set out to identify mechanisms of self-protection employed by the FB1 producer Fusarium verticillioides. FB1 biosynthesis was shown to be compartmentalized, and two cluster-encoded self-protection mechanisms were identified. First, the ATP-binding cassette transporter Fum19 acts as a repressor of the FUM gene cluster. Appropriately, FUM19 deletion and overexpression increased and decreased, respectively, the levels of intracellular and secreted FB1. Second, the cluster genes FUM17 and FUM18 were shown to be two of five ceramide synthase homologs in Fusarium verticillioides, grouping into the two clades CS-I and CS-II in a phylogenetic analysis. The ability of FUM18 to fully complement the yeast ceramide synthase null mutant LAG1/LAC1 demonstrated its functionality, while coexpression of FUM17 and CER3 partially complemented, likely via heterodimer formation. Cell viability assays revealed that Fum18 contributes to the fungal self-protection against FB1 and increases resistance by providing FUM cluster-encoded ceramide synthase activity.

INTRODUCTION

Filamentous fungi produce numerous secondary metabolites that are, per definition, not required for growth or development, as is the case for primary metabolites. Instead, secondary metabolites confer an advantage to producing fungi under specific environmental conditions, oftentimes mediating intra- and interspecies communication, pathogenicity, and defense against physical damage or competitors (1, 2). Mycotoxins are fungal secondary metabolites that are toxic to animals and accumulate in crops, but they often exhibit toxicity to other eukaryotes, including fungi (3, 4). This raises the question: how do fungi protect themselves from the mycotoxins they produce? In fungi, genes directly involved in the biosynthesis of a secondary metabolite are generally located next to one another in biosynthetic gene clusters (5). Such clusters often comprise one or more genes that confer self-protection against the toxic product of the cluster. Mechanisms of self-protection include (i) duplicated or resistant targets, generally enzymes of primary metabolism; (ii) detoxification by biotransformation to less harmful derivatives; and (iii) specific transporters that secrete toxins from the cytosol (6).

Among the most studied fungal mycotoxins are fumonisins of the B series (FBs), secondary metabolites produced by Fusarium and Aspergillus species (7). The predominant FB producer Fusarium verticillioides is the most prevalent fungus associated with contamination of corn and corn-derived products worldwide, and the consumption of FB-containing food and feed has been correlated with a number of human and animal diseases (8, 9). FB are polyketide-derived aminopentol compounds with two tricarballylic esters (10, 11), and particularly the analog FB1 (Fig. 1) is an efficient inhibitor of ceramide synthase, a key enzyme in sphingolipid biosynthesis (12). Appropriately, FB1 competes reversibly with both sphinganine and acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) in the ceramide synthase active site (13). During plant infection, or after consumption of contaminated food and feed, inhibition of ceramide synthase results in the accumulation of free sphingoid bases, primarily sphinganine (9, 14, 15). Toxicity is attributed to apoptotic processes initiated in response to sphingoid base accumulation rather than reduced sphingolipid biosynthesis (16).

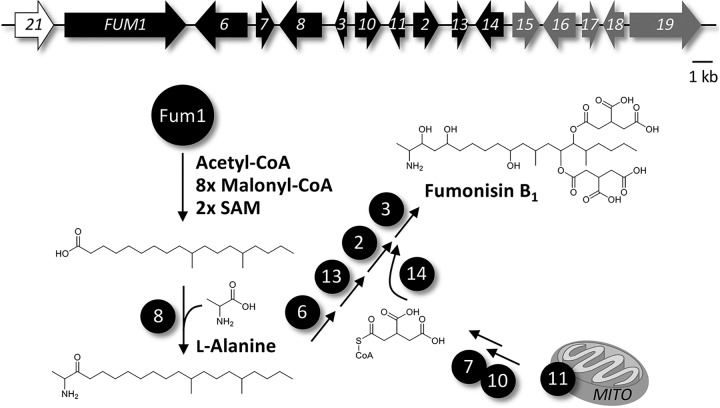

FIG 1.

Fumonisin (FUM) biosynthetic gene cluster, and proposed biosynthetic pathway toward fumonisin B1 (FB1). Genes encoding FB1 biosynthetic enzymes are depicted in black. FUM21 (white) encodes the cluster-specific transcription factor, while the coregulated cluster genes FUM15 to FUM19 (gray) do not participate in FB1 biosynthesis.

Complex sphingolipids consist of a ceramide backbone, i.e., sphingosine attached to a fatty acid (C14 to C26) in an amide linkage, with a polar headgroup (17). They are essential components of eukaryotic cellular membranes, which are involved in maintaining proper membrane structure and anchoring membrane-associated proteins. Sphingolipid biosynthesis is compartmentalized: the first steps take place in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), while complex sphingolipids are produced in the Golgi apparatus (18). As indicated, precursors/degradation products of sphingolipids act as second messengers, therefore, sphingolipid metabolism is tightly controlled (16). Thus, when applied in a targeted manner, sphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitors can serve as treatment against severe human diseases, e.g., cancer, Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes, that are (among other defects) correlated with a deregulated sphingolipid metabolism (17, 19, 20).

In F. verticillioides, the FB biosynthetic gene cluster (FUM) includes 16 genes: FUM1 to FUM3, FUM6 to FUM8, FUM10, FUM11, FUM13 to FUM19, and FUM21 (11, 21). FB biosynthesis is initiated when the polyketide synthase Fum1 catalyzes synthesis of an octadecanoic acid precursor, which then undergoes condensation with l-alanine, a reaction catalyzed by the aminotransferase Fum8 (Fig. 1). The cluster encodes a tricarboxylate transporter, Fum11, likely functioning as a mitochondrial carrier protein and providing the substrate for Fum7 and Fum10 to produce CoA-activated tricarballylic acid. Two of these molecules are attached to the polyketide backbone by Fum14, while the final biosynthetic step is performed by the dioxygenase Fum3 (22). In addition, the cluster encodes a transcriptional regulator, Fum21, belonging to the GAL4-like Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor family (21). Despite all of the functional analyses of FUM cluster genes, the functions of FUM15 to FUM19 remain unclear (11). Also, the mechanism that protects F. verticillioides ceramide synthases from the inhibitory effect of FB has not yet been elucidated. While FB1 has antifungal activity, in particular against FB nonproducers, F. verticillioides was more resistant to externally added FB1 (23). Knowledge of this process has potential to provide new insights into methods to block FB production in crops and thereby improve food safety.

The similarity of Fum17 and Fum18 to ceramide synthases and of Fum19 to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters suggests a role for these proteins in FB self-protection (11). In the present work, we demonstrate that Fum19 is involved in FUM cluster regulation, acting as a repressor of biosynthesis. Point mutations of the identified ATP-binding domains indicated that ATP hydrolysis and possibly transport are required for Fum19 activity. Moreover, confocal microscopy showed that the aminotransferase Fum8 colocalizes with Fum17, Fum18, and the fungal ceramide synthase Cer1 in ER-derived vesicles. The results presented here show that Fum18 constitutes a FUM cluster-encoded ceramide synthase as an additional toxin-targeted enzyme, which contributes to ceramide biosynthesis and thereby decreases self-poisoning.

RESULTS

The ABC transporter Fum19 acts as a repressor of the FUM gene cluster.

In order to analyze the influence of FUM17, FUM18, and FUM19 on FB biosynthesis and fungal self-protection, we generated single deletion mutants in F. verticillioides strain M-3125. We also generated both double FUM17/18 and triple FUM17-19 deletion mutants to test for functional redundancy. Because FB1 is the FB analog produced in greatest abundance by F. verticillioides, i.e., FB1 constitutes approximately 80% of total FB (11), we used it as a marker for FB production. FB1 production was quantified in shaking cultures by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC-HRMS). The identity of the chromatographic peak corresponding to FB1 was verified by comparison with an FB1 reference (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material).

Chemical analyses of FB1. (A) HPLC-HRMS comparison of FB1 produced by the F. verticillioides WT with the chemical standard. (B) Extracted ion chromatograms for m/z = 722.3957 ± 5 ppm and measured accurate masses. (C) Intracellular accumulation of FB1 in Δfum17-19, Δfum19, and OE::FUM19 mutants. Extracts from washed mycelium were analyzed via HPLC-HRMS. (D) The fungal biomasses of FUM17, FUM18, and FUM19 mutants were determined after freeze-drying the harvested mycelium. Indicated strains were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln shaking culture for 7 days. FB1 production and biomass of the WT were arbitrarily set to 100%, respectively. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). For statistical analysis, the mutants were compared to the WT using the Student t test (*, P < 0.05). Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB (104.7KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

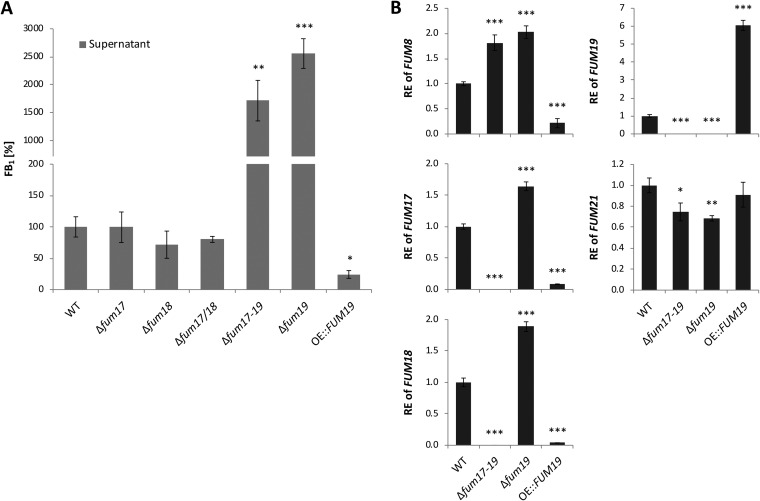

Single and double deletion of FUM17 and FUM18 did not affect FB1 production (Fig. 2A), confirming previously reported results (11). However, deletion of FUM19, in both wild-type (WT) and Δfum17/18 backgrounds, resulted in significant overproduction of FB1 in the supernatant as well as in the extracted mycelium (Fig. 2A; Fig. S1C). In contrast, FUM19 overexpression resulted in a significant reduction in FB1 production (Fig. 2A; Fig. S1C). Despite elevated FB1 levels in Δfum19 mutants, fungal biomass was not decreased compared to the WT (Fig. S1D). The overall production of FB1 correlated very well with FUM cluster gene expression. Indeed, the Δfum19 mutant exhibited elevated expression of FUM17 and FUM18, as well as FUM8, which served as a marker for FUM genes encoding FB biosynthetic enzymes (Fig. 2B). Together, these results indicated that FUM19 negatively impacts expression of other FUM cluster genes, which in turn indicated a repressive role of Fum19 in FB biosynthesis.

FIG 2.

FB1 production and FUM gene expression in FUM17, FUM18, and FUM19 mutants. (A) FB1 was relatively quantified in shaking cultures. Indicated strains were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln for 7 days, and cell-free culture fluids were analyzed via HPLC-HRMS. The production level of the WT was arbitrarily set to 100%. The data are mean values ± standard deviation (n = 3). (B) After 2 days of cultivation, the relative expression (RE) was determined by qRT-PCR. The WT gene expression was arbitrarily set to 1. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). For statistical analysis, the mutants were compared with the WT using the Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

We hypothesized that this regulatory role of Fum19 may be linked to its ability to bind and transport FB1 at the expense of ATP. In order to test whether ATP hydrolysis is required for this regulatory role, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of the two putative Fum19 ATP-binding domains (Fig. 3A). The domains were identified by comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of Fum19 to the ATP-binding domain of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium histidine permease, HisP, which has been structurally resolved and thoroughly analyzed with respect to structure-function relationships (24, 25). The comparison led to identification of two sets of amino acids (K631/K1260 and D743/D1397) predicted to be critical for binding of ATP to Fum19 (25). In an attempt to disable ATP-binding and thereby block the presumed transport function of Fum19, we introduced two sets of point mutations into cloned FUM19 that were designed to replace the K631/K1260 (FUM19Kmut) or D743/D1397 (FUM19Dmut) residues in the Fum19 protein (Fig. 3A; Fig. S2A). In locus exchange of Δfum19 with the WT gene, FUM19C, restored FB1 production to close to WT levels (Fig. 3B). However, exchange with either FUM19Kmut or FUM19Dmut did not complement the Δfum19 phenotype (Fig. 3B). We confirmed that FUM19 expression was comparable for all complemented strains (Fig. S2B). These experiments suggested that ATP hydrolysis, and possibly transport, are tightly coupled to the regulatory role of Fum19. However, because extracellular FB1 accumulated upon deletion or point mutation of FUM19, we can hypothesize that either F. verticillioides harbors additional FB1 exporters or that the molecule is able to passively cross the plasma membrane.

FIG 3.

Deletion and point-mutation of FUM19 upregulates the FUM cluster. (A) Schematic representation of the two sets of point mutations inserted into the ATP-binding domains (ATP BD) of FUM19. (B) The indicated strains were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln shaking culture for 7 days and analyzed by HPLC-HRMS. Culture fluids were measured directly, while metabolite extraction from washed mycelium was performed for intracellular FB1 levels. The production level of the WT was arbitrarily set to 100%. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). (C) After 2 days of cultivation, relative expression (RE) was determined by qRT-PCR. The WT gene expression was arbitrarily set to 1. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). For statistical analysis, strains were compared as indicated using the Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

FUM19 point mutation and FB1 feeding of FUM19 and FUM21 mutants. (A) The two ATP-binding domains of Fum19 were identified by comparison to the respective domain of HisP (UniProtKB P02915). Identical amino acids are highlighted in gray, and residues chosen for point mutation are marked. (B) Expression analysis of FUM19 point-mutated strains, grown in an ICI/6 mM Gln shaking culture for 2 days. (C) For FB1 feeding, the indicated strains were grown in an ICI/6 mM Gln shaking culture for 1 or 2 days prior to the addition of water (untreated) or 10 μg/ml FB1 for 2 h. The relative expression (RE) was determined by qRT-PCR, and WT gene expression (2 days) was arbitrarily set to 1. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). For statistical analysis, treated and untreated samples were compared using the Student t test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.1 MB (141.6KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Fum17 and Fum18 are partially regulated by Fum21.

Expression analysis via quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of FUM19 deletion and overexpression strains revealed that the cluster-specific transcription factor gene FUM21 was not coordinately up- or downregulated, respectively (Fig. 2B). This suggested that the negative feedback mediated by Fum19 does not occur via FUM21 repression on a transcriptional level.

To investigate this further, we deleted FUM21 in the WT and Δfum19 mutant strains of F. verticillioides. In both genetic backgrounds, the deletion completely abolished FB1 production, confirming that Fum21 is essential for biosynthesis (Fig. 3B). However, in contrast to FUM8, FUM17 and FUM18 expression was only partially under the control of Fum21, as their expression was induced in ∆fum19/∆fum21 double mutants (Fig. 3C). It is noteworthy that this expression occurred in the complete absence of FB1 production, highlighting that cluster activation in the Δfum19 background is not a consequence of intracellular accumulation of FB1. Nonetheless, addition of exogenous FB1 induced expression of FUM8, FUM17, FUM18, and FUM19, but not FUM21, in the WT background (Fig. S2C). Upregulation of FUM8, FUM17, and FUM18 by the addition of FB1 was independent of the presence of a functional FUM19 but largely dependent on the presence of a functional FUM21 (Fig. S2C).

Taken together, these experiments revealed complex and intertwined regulation mechanisms of the FUM gene cluster: FUM19 repressed FUM cluster genes in the WT background, whereas deletion of FUM19 strongly upregulated FB1 production. FUM21 was essential for FB1 production, and both FUM8 and FUM19 were tightly regulated by the transcription factor. In contrast, expression of FUM17 and FUM18 could still be induced in the Δfum21 background.

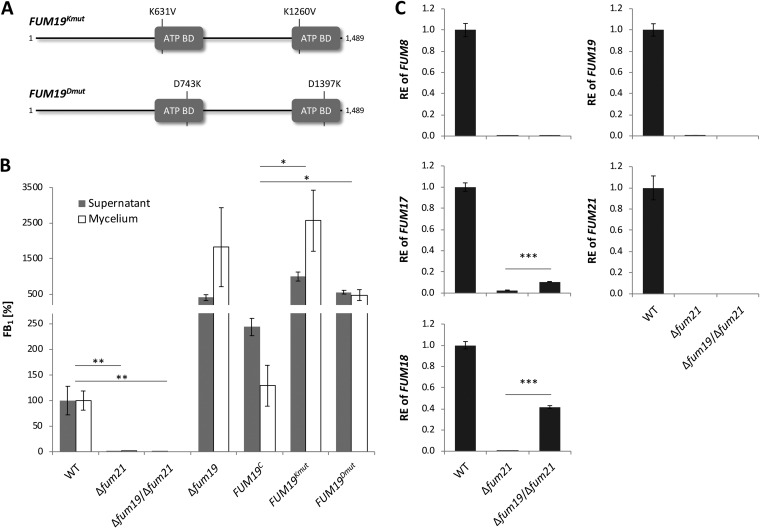

Phylogenetic relationships of Fum17 and Fum18 to other fungal ceramide synthases.

An analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of Fum17 and Fum18 revealed that both proteins have a TRAM/LAG1/CLN8 (TLC) protein domain (IPR006634), a domain that is present in all eukaryotic ceramide synthases described to date (26). To gain insight in the relationships of Fum17 and Fum18 to other fungal ceramide synthases, we inferred a phylogenetic tree using alignments of predicted amino acid sequences retrieved by BLAST analysis of selected genome sequences at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)-GenBank and Joint Genome Institute. Because Fusarium is a member of the phylum Ascomycotina (class Sordariomycetes), most sequences were retrieved from other ascomycetous fungi, including species in classes Dothideomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Leotiomycetes, Pezizomycetes, Saccharomycetes, and Sordariomycetes. We also retrieved sequences from five species in phylum Basidiomycotina. In the resulting phylogenetic tree, fungal ceramide synthases were resolved into two major clades, designated CS-I and CS-II (Fig. 4). Most species of the Ascomycotina and Basidiomycotina included in this analysis had at least one ceramide synthase in each of the major clades. However, the LAG1 and LAC1 genes from yeast species were an exception to this; LAG1 and LAC1 were both resolved within clade CS-I and were relatively closely related to one another. Fusarium species with the FUM cluster had three ceramide synthase genes (CER1, CER2, and CER3) located outside the cluster, in addition to the cluster genes FUM17 and FUM18. FUM17 homologs from Fusarium fujikuroi and Fusarium proliferatum were excluded from the analysis because the gene was pseudogenized in these species. In the tree, FUM17 and CER1 (FVEG_06971) were resolved within clade CS-I, while FUM18, CER2 (FVEG_12887), and CER3 (FVEG_15375) were resolved in clade CS-II (Fig. 4). Fusarium solani was unique in that it had a fourth non-FUM-cluster ceramide synthase gene that was resolved within clade CS-I and that was relatively distantly related to other Fusarium genes, but instead was most closely related to homologs in the sordariomycete species Gaeumannomyces tritici and Pyricularia oryzae (Fig. 4). Conclusively, phylogenetic analysis revealed that Fum17 and Fum18 are closely related to fungal ceramide synthases.

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing two major clades (CS-I and CS-II) of fungal ceramide synthases and the positions of Fum17 and Fum18 within the clades. The tree was inferred by maximum-likelihood analysis of alignments of predicted amino acid sequences of selected ceramide synthases from the ascomycete classes Dothideomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Leotiomycetes, Pezizomycetes, Saccharomycetes and Sordariomycetes. Sequences of five basidiomycete species were also included in the analysis, and the tree was rooted with rat and human sequences. Accession numbers for protein sequences are indicated after species names. Joint Genome Institute accession numbers are preceded by JGI; all other accessions are from NCBI/GenBank. In the Fum17 and Fum18 clades, the five-digit numbers after some of the Fusarium species names are NRRL strain designation. The genome sequences of these are present in GenBank, but they are not annotated. Numbers near branches are bootstrap values based on 1,000 pseudoreplicates. Values of <70 are not considered to be significant and therefore are not shown.

Fum17, Fum18, Fum8, and Cer1 colocalize in ER-derived vesicles.

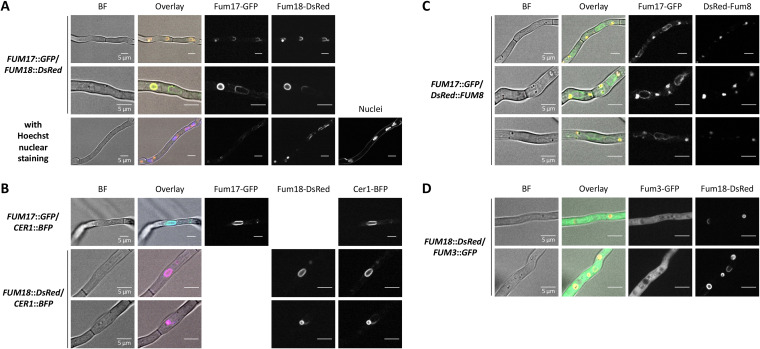

Next, we performed localization studies by confocal microscopy of Fum17 and Fum18, C-terminally fused to green and red fluorescent proteins (GFP/DsRed), respectively. We made sure that the fluorescent proteins did not give signals when excited with inappropriate wavelengths (Fig. S3). Fum17-GFP and Fum18-DsRed were shown to colocalize with each other in the perinuclear ER, and their localization around the nuclei was verified by nuclear visualization, i.e., staining with the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342. In addition, they colocalized in the membrane of small/medium-sized vesicles (ca. 1 to 2 μm) which were independent of the nuclei (Fig. 5A). Full colocalization of both proteins with one of the three ceramide synthase homologs, Cer1 fused to blue fluorescent protein (BFP), confirmed their presence in the perinuclear ER and in ER-derived vesicles (Fig. 5B). The presence of DsRed-Fum8 (N-terminal fusion) in the vesicles, but not in the perinuclear ER, revealed that early FB biosynthesis takes place in these compartments (Fig. 5C). Intriguingly, the final FB biosynthetic step performed by the dioxygenase Fum3 takes place in the cytoplasm, as shown by C-terminal GFP fusion (Fig. 5D). In summary, these results strongly indicated that biosynthesis of both sphingolipids and inhibitors thereof partially overlap, while the final biosynthetic step is separate from Fum17, Fum18, and Cer1.

FIG 5.

Fum3, Fum8, Fum17, Fum18, and Cer1 localization in F. verticillioides. Confocal microscopy for localization of Fum17-GFP and Fum18-DsRed (A), Cer1-BFP (B), DsRed-Fum8 (C), and Fum3-GFP (D). Conidia were inoculated in ICI/6 mM Gln and grown as a standing culture overnight. The indicated double mutants were analyzed for GFP, DsRed, and/or BFP fluorescence. The cells were untreated, except when indicated (nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 in panel A). Shown are individual channels in black/white, bright-field (BF) images and an overlay with the BF in color.

Confocal microscopy for localization of Fum17-GFP and Fum18-DsRed. Conidia were inoculated in ICI/6 mM Gln and grown as a standing culture overnight. The indicated strains were analyzed for GFP, DsRed, and BFP fluorescence. Shown are individual channels in black/white, bright-field (BF) images and an overlay with BF in color. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.8 MB (818.6KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

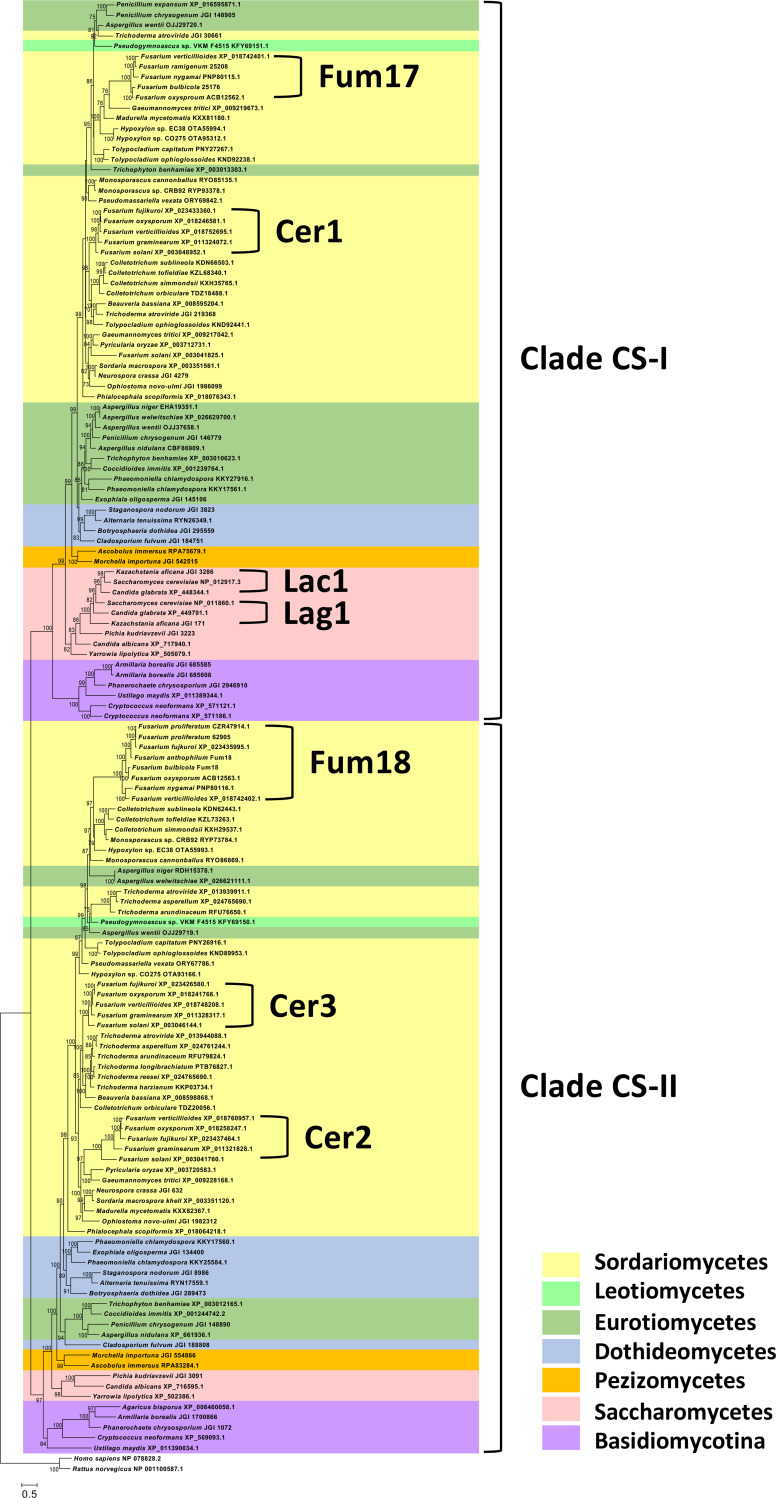

Fum18 is a functional ceramide synthase.

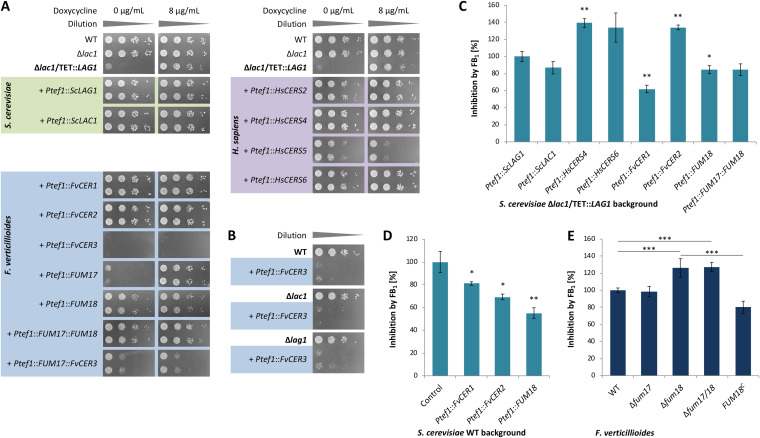

In order to investigate whether Fum17 and Fum18 function as ceramide synthases, we established a yeast complementation assay. As indicated above, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome encodes two paralogs of clade CS-I with redundant function, Lag1 and Lac1. LAG1/LAC1 double deletion mutants are nonviable or very slow growing (27, 28). Therefore, we constructed a conditional null mutant, in which LAG1 is under the control of the inducible TETON promoter (29) in the Δlac1 background. The resulting strain could grow only in the presence of doxycycline (Fig. 6A). As shown, the two S. cerevisiae ceramide synthase genes, either LAG1 or LAC1, could rescue the lethal phenotype when expressed from a plasmid under the control of the constitutive TEF1 promoter (Ptef1) (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Yeast complementation and resazurin cell viability assays for analyzing ceramide synthase functionality and inhibition, respectively. (A) The conditionally lethal strain S. cerevisiae Δlac1/TET::LAG1 was complemented with yeast (green), F. verticillioides (blue) and human (violet) ceramide synthase homologs. Complementation of the null mutant was evaluated in the absence of inducer (0 μg/ml doxycycline) after 2 days on SD–Ura (n = 2). (B) Plasmid Ptef1::FvCER3 was introduced into S. cerevisiae WT, Δlac1, and Δlag1 backgrounds. (C to E) Resazurin assay with S. cerevisiae Δlac1/TET::LAG1 strains (500 μg/ml FB1) (C), S. cerevisiae WT strains (500 μg/ml FB1) (D), and F. verticillioides FUM17/18 mutants (250 μg/ml FB1) (E). Growth curves used for the calculations are shown in Fig. S4. In each case, inhibition of the control strain was arbitrarily set to 100%. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). For statistical analysis, strains were compared as indicated or with the control using the Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Resazurin cell viability assays. (A) Plasmid-harboring S. cerevisiae Δlac1/TET::LAG1 strains were grown in SD–Ura without doxycycline for 24 h. (B) Plasmid-harboring S. cerevisiae WT strains were grown in SD–Ura for 24 h. (C) F. verticillioides WT and FUM17/18 mutants were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln for 21 h. Fluorescence was detected every 30 min. Each strain was incubated under the addition of water (untreated) or FB1 as indicated. To account for medium- and compound-related variations, measurements of each sample were normalized against its lowest starting value. The data are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). Download FIG S4, PDF file, 0.2 MB (253.8KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

We expressed the five F. verticillioides TLC domain proteins (CER1, CER2, CER3, FUM17, and FUM18) in the Δlac1/TET::LAG1 background. As shown, expression of CER1, CER2, or FUM18 fully complemented the S. cerevisiae null mutant in the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 6A). In contrast, FUM17 and CER3 did not complement the mutant, and the expression of CER3 was even toxic for S. cerevisiae (Fig. 6A and B). Intriguingly, expression of a bicistronic FUM17::CER3 construct partially complemented Δlac1/TET::LAG1 in the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 6A). This suggested that Cer3 is able to form nonfunctional heterodimers with both Lag1 and Lac1, while it can functionally dimerize with Fum17. These data indicated that the FUM gene cluster encodes a functional ceramide synthase, Fum18, while Fum17 can potentially contribute to ceramide biosynthesis by interaction with Cer3.

Fum18 contributes to resistance against FB1.

In order to test whether Fum18, Cer1, and Cer2 are insensitive to FB1, we established a resazurin cell viability assay for S. cerevisiae and Fusarium strains generated during this study. The blue nonfluorescent dye resazurin is reduced to its pink highly fluorescent derivative resorufin, and this turnover is proportional to respiration processes in living cells, including fungi (30, 31). In a previous study, real-time monitoring of bacterial growth revealed that fluorescence was proportional to cell density, allowing the assay to be used to compare treatments that differ in effect on growth (32). We adapted this protocol for S. cerevisiae and F. verticillioides strains exposed to FB1, where the difference in fluorescence maxima between nontreated and FB1-treated cells represented the growth-inhibitory effect for a given strain and was independent of the growth rate (Fig. S4). Both fungi exhibit an intrinsic tolerance to FB1; therefore, relatively high concentrations of FB1 (250 to 500 μg/ml) were used in experiments to observe differences in inhibition (Fig. 6C to E).

In order to include human ceramide synthases in the susceptibility tests, CERS2, CERS4, CERS5, and CERS6 were amplified from cDNA of the colon cancer cell line HT29-MTX (33). Sequence analysis of the cDNA identified a previously unreported insertion in CERS6 that resulted in a frameshift and early termination, producing a predicted protein of 349 rather than 384 amino acids (K334 → KVLVILTCFYSTGVQG). Although these human ceramide synthases harbor a homeobox (HOX) domain (IPR001356) and thereby differ structurally from the fungal homologs, CERS2/CERS4/CERS6 fully, and CERS5 partially complemented Δlac1/TET::LAG1 (Fig. 6A).

We first analyzed Δlac1/TET::LAG1 strains complemented with either one of the fungal or human ceramide synthase genes and grown in the absence of inducer (Fig. S4A). Compared to yeast Lag1 and Lac1, human CERS4 and CERS6 were more strongly inhibited by FB1 (500 μg/ml), although the difference for CERS6 was not significant (Fig. 6C). Among the F. verticillioides homologs, Cer2 was more strongly inhibited than Cer1 and Fum18. Coexpression of FUM17 and FUM18 did not further increase tolerance to FB1, suggesting that they do not cooperate in FB1 resistance (Fig. 6C). Based on this result, we can assume that Fum18 is not an intrinsically more resistant ceramide synthase variant but that it contributes to fungal self-protection by providing additional cluster-encoded ceramide synthase activity. To confirm this assumption, we expressed CER1, CER2, and FUM18 in WT S. cerevisiae to generate strains with a third ceramide synthase gene in addition to LAG1 and LAC1. The results of growth assays indicated that heterologous expression of any of these F. verticillioides genes significantly increased tolerance of S. cerevisiae to FB1 (Fig. 6D; Fig. S4B). The finding for CER2 was surprising given that initial assessment indicated that Cer2 was less tolerant to FB1 than Cer1 and Fum18 (Fig. 6C).

Finally, we examined germinating conidia of the Δfum17, Δfum18, and Δfum17/18 mutant and WT strains of F. verticillioides in the presence or absence of FB1 (250 μg/ml). Young hyphae of the single and double deletion mutants of FUM18 were more susceptible to FB1, which could be complemented by reintroduction of the full-length gene in the Δfum18 background (Fig. 6E; Fig. S4C). In summary, Fum18 is a functional ceramide synthase which confers additional cluster-encoded enzymatic activity, and thereby fungal self-protection against the produced ceramide synthase inhibitor FB1.

DISCUSSION

The biosynthesis of fungal secondary metabolites is highly regulated not only in terms of cluster gene expression but also concerning the spatial organization of the encoded enzymes. Like all eukaryotes, fungal cells contain small organelles and vesicles able to embed enzymes and potentially compartmentalize biosynthetic pathways. This mechanism has several advantages: (i) it concentrates enzymes in a smaller space, improving multienzymatic catalysis; (ii) it reduces cross-reactions with other biosynthetic pathways; and (iii) in the case of production of mycotoxins, it may protect cells from self-poisoning (34).

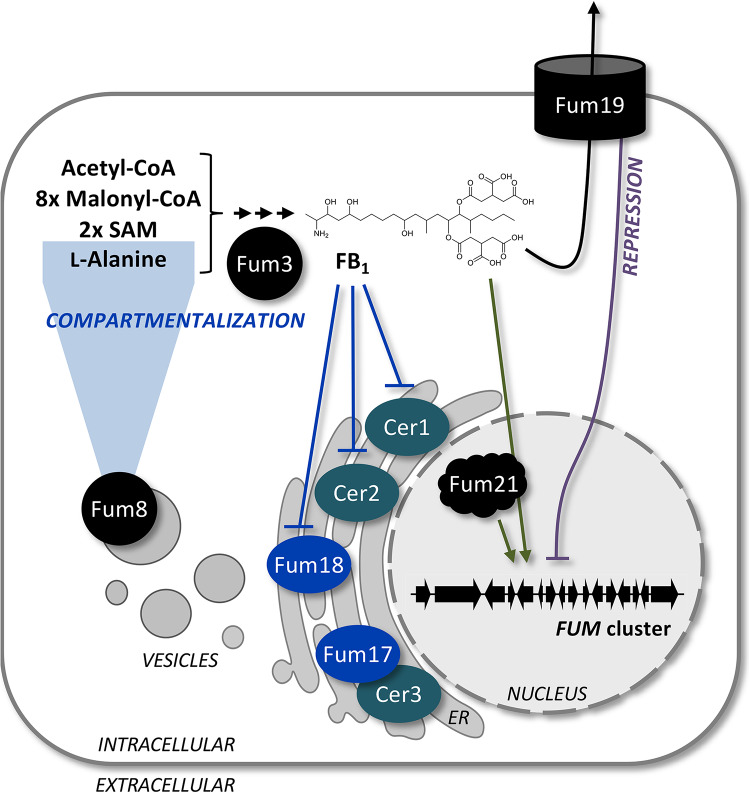

In the present study, we identified highly sophisticated compartmentalization, regulation and self-protection mechanisms, which ensure tightly controlled levels of the ceramide synthase inhibitor FB1 in F. verticillioides. Compartmentalization of FB biosynthesis makes sense for two reasons. First, compartmentalization allows for spatially restricted and thereby controlled biosynthesis. The early FB pathway enzyme Fum8 was localized to ER-derived vesicles (Fig. 7), and indeed the duplicated target enzyme, the ceramide synthase Fum18, was found to colocalize with Cer1 in these vesicles. It is noteworthy that ceramide biosynthesis likely occurs on the perinuclear ER (35), which was nearly completely devoid of Fum8. Second, the last biosynthetic step, performed by Fum3, was localized to the cytoplasm, revealing that the most potent compound FB1 is separate from the fungal ceramide synthases (36). Appropriately, this compartmentalization strategy likely helps to prevent self-poisoning.

FIG 7.

Compartmentalization and self-protection strategies of the FB1 producer F. verticillioides. Fum8 is localized to ER-derived vesicles, in which also Fum17, Fum18, and Cer1 are found, while Fum3 is cytoplasmic. Fum18 is a functional ceramide synthase required for self-protection by providing additional enzymatic activity and thereby supporting Cer1 and Cer2. Fum17 could contribute to self-protection by forming a functional heterodimer with Cer3. The ABC transporter Fum19 is formally a repressor of the FUM gene cluster. This was supported by the fact that FB1 feeding triggered cluster gene expression, an effect which was mainly dependent on the cluster-specific transcription factor Fum21.

Although Fum19 was not shown to be essential for FB1 export, the results reported here indicate that this ABC transporter has an important role in the regulation of expression of FUM cluster genes and thereby self-protection. This was supported by several lines of evidence. Deletion (in two different backgrounds) and overexpression of FUM19 induced and reduced, respectively, the expression of other FUM genes, which is consistent with a role as repressor for Fum19 (Fig. 7). An earlier study on F. verticillioides Δfum19 reported a slight increase in FB1 and a significant decrease in its direct precursor FB3, indicating a shift toward the final product and thereby an upregulation of the biosynthetic pathway (11). We suggest that FB1 production in the WT background was not at its maximum under our cultivation conditions (fully synthetic 1-week culture), so that a more drastic increase could be observed for Δfum19. Noteworthy, FUM19 overexpression and a detailed analysis of intra- and extracellular FB1 levels had not been performed. On a transcriptional level, FUM19 deletion in the Δfum21 background resulted in derepression of the resistance gene FUM18 (and FUM17), indicating a regulatory circuit that directly targets FUM gene expression in the complete absence of either Fum21 or the final product FB1. Taken together, this indicates that Fum19 is involved in a negative-feedback loop to moderate FB1 levels, while Fum19 dysfunction, here mimicked by gene deletion and point mutations, gives a cue to upregulate expression of FUM cluster genes.

Point mutations of FUM19 confirmed that ATP hydrolysis and thereby possibly transport are tightly linked to its function, although final proof that Fum19 is a true exporter is still lacking. At this point, it cannot be excluded that ATP sensing is (one of) the vital role(s) of Fum19. Nevertheless, these data are consistent with earlier reports, in which deletion of the associated ABC transporter gene resulted in an upregulated secondary metabolite biosynthesis, i.e., of gibepyrone and beauvericin in F. fujikuroi and of sirodesmin in Leptosphaeria maculans (37–39). Noteworthy, the beauvericin ABC transporter Bea3 was successfully localized to the plasma membrane, although it was not essential for secretion (38). This implies either that these mycotoxins may passively cross the plasma membrane or that additional cluster-independent exporters are responsible for their secretion. As an example, redundancy of exporters has been observed for cercosporin in Cercospora nicotianae: although the gene cluster encodes a transporter of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), two exporters outside of the cluster were required for self-protection (40, 41). Interestingly, cluster upregulation upon deletion seems to be specific to ABC transporter genes, while the loss of MFS transporters has been mainly correlated with a downregulation of the cluster (41, 42).

Because the results from our analysis of FUM19 function provided new insights into FB biosynthesis, we decided to reassess the functions of FUM17 and FUM18. In the present study, we demonstrated that Fum18 can function as a ceramide synthase on its own and that it contributes to FB self-protection by providing supplementary ceramide synthase activity (Fig. 7). FB1 inhibited growth of FUM18 deletion mutants during spore germination, but not when produced at a later stage in liquid cultures, since fungal biomass of FUM18 mutants was not reduced compared to the WT. Indeed, it has been suggested that inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism is likely to be more disturbing for actively growing cells (16, 36), i.e., during spore germination in this case. In addition, Fum17 could contribute to FB self-protection by forming a heterodimer with Cer3. The later point is supported by the fact that homo- and heterodimers of Lag1/Lac1 have been reported for yeast ceramide synthase complexes (43).

The expression of additional ceramide synthase genes to decrease the toxic effect of sphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitors seems to be conserved. In this regard, FB1 and AAL-toxin display a highly similar chemical structure, and their biosynthesis is conferred by homologous gene clusters (44, 45). The F. fujikuroi FUM cluster and the Alternaria alternata AAL-toxin cluster harbor a FUM18 homolog but lack a functional FUM17 (45, 46). Alt7 of the AAL-toxin cluster was suggested to be a ceramide synthase homolog, although direct functional tests have not been reported (45). However, prior to that, it was shown that resistance in tomato to AAL-toxin-producing isolates of A. alternata was mediated by the plant ceramide synthase Asc-1. Tomato Asc-1 prevented programmed cell death which was otherwise induced upon disruption of sphingolipid biosynthesis by AAL-toxin (47, 48). Therefore, the presence of an additional target enzyme is a successful resistance strategy for both the plant and the fungal side.

The present study revealed that filamentous fungi have at least two ceramide synthase genes. Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that they group into two distinct clades (CS-I and CS-II) and that within a given species, one is a member of CS-I and the other is a member of CS-II. Fusarium spp. and FB-producing Fusarium spp. can have three and (up to) five homologs, respectively. The phylogenetic relationships of FUM17 and FUM18 and their presence in the FUM cluster mirror the relationships and presence of two ceramide synthase genes in fungal genomes. The nesting of FUM17 and FUM18 within clades of sordariomycete genes suggests that they did not evolve from Fusarium genes, but instead evolved from genes in a sordariomycete ancestor. On a biochemical level, evidence suggests that fungal clade CS-I ceramide synthases provide precursors for glycosylinositol phosphorylceramide-type complex sphingolipids, while clade CS-II enzymes feed the glucosylceramide pool (49, 50). Deletion of Fusarium graminearum BAR1, the FvCER3 ortholog, resulted in complete loss of glucosylceramide biosynthesis (51). Although Cer3 was not functional on its own in the yeast complementation assay, this does not exclude its functionality in F. verticillioides in vivo. It remains to be elucidated whether Cer2 and Fum18 homologs also contribute to the glucosylceramide pool in FB-producing Fusarium spp.

The yeast ceramide synthase assay developed in this study could be used to test novel (chemical) derivatives of sphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitors for improved or more specific ceramide synthase inactivation. The six human enzymes exhibit specificity with respect to carbon-chain length of fatty acyl-CoAs that they can use as the substrates (18). As a result, modification of FB1 to mimic CoA precursors of a specific chain length has potential as a strategy to inhibit one ceramide synthase without affecting others. Targeting individual human enzymes would have powerful therapeutic applications, such as specifically inactivating CERS6 upregulated during development of multiple sclerosis (17). In addition, the disruption of fungal sphingolipid metabolism has been suggested as an efficient antifungal strategy (50).

In summary, we presented a comprehensive analysis of compartmentalization strategies and cluster-encoded self-protection mechanisms involved in FB biosynthesis in F. verticillioides. The final step in FB biosynthesis, performed by the dioxygenase Fum3, was localized to the cytoplasm and does thereby not colocalize with fungal ceramide biosynthesis in the ER. In ER-derived membrane structures, Fum18 was shown to protect the fungal ceramide synthases Cer1 and Cer2 by providing FUM cluster-encoded ceramide synthase activity. In addition, the ABC transporter Fum19 indirectly contributes to self-protection by modulating FB levels through its effects on expression of FUM cluster genes. These findings provide insight into FB self-protection in fungi and point to novel methods for ceramide synthase-related drug discovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

F. verticillioides media and growth conditions.

F. verticillioides M-3125 (52) was used as parental strain for the analysis of the FUM gene cluster (FVEG_00315 to FVEG_00329) (11, 21, 22). General maintenance of fungal strains was performed on solidified complete medium (53). For the cultivation of strains in liquid culture, 100 ml of Darken preculture (54) in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks was inoculated with a piece of mycelium and shaken for 3 days at 180 rpm and 28°C. Then, 250 μl of the preculture was transferred to 100 ml of synthetic ICI medium (Imperial Chemical Industries, Ltd., London, UK) (55) supplemented with 6 mM glutamine (Gln) and then shaken under the same conditions for 2 or 7 days for gene expression or FB1 analyses, respectively.

Plasmid constructions.

Vector assembly was achieved with yeast recombinational cloning (56, 57). Deletion vectors harbored ∼1 kb upstream and downstream flanks of the gene of interest, as well as a deletion cassette. Flanks were amplified using proofreading polymerase, primer pairs 5F/5R and 3F/3R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), as well as F. verticillioides genomic DNA (gDNA). FUM17, FUM18 and FUM19 were deleted by exchange with the hygromycin B resistance gene under the control of A. nidulans PgpdA; for that purpose, hphR was amplified from pUC-hph (58) with hph_F/hph_R. Furthermore, deletion of FUM21 was achieved with the nourseothricin resistance gene under the control of A. nidulans PtrpC, and natR was amplified from pZPnat1 (GenBank accession no. AY631958.1) with nat1_F/nat1_R. S. cerevisiae BY4741 (Euroscarf, Oberursel, Germany) was transformed with the obtained fragments, as well as with the XbaI/HindIII-digested shuttle vector pYES2 (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), yielding the deletion constructs (Fig. S5 to S7).

Verification of FUM17 and FUM18 single mutants by diagnostic PCR and Southern blot. (A) Deletion of FUM17 via homologous recombination with the hygromycin B resistance cassette (hphR). Diagnostic PCR verified the correct recombination of 5′ and 3′ flanks, and the absence of WT gene for three independent transformants. Genomic DNA of transformants and WT was digested with EcoRI, and the 3′ flank was applied for probing. (B) Deletion of FUM18 via homologous recombination with hphR. Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI, and the 5′ flank was applied for probing. (C) Complementation of Δfum18 with the full-length gene and nourseothricin resistance cassette (natR). Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI, and the 5′ flank was applied for probing. FUM18C T9 showed an ectopic integration and was not chosen for further analyses. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 1.8 MB (1.9MB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

For in locus complementation of FUM18 and FUM19 (Fig. S5C and S7A), the full-length genes, including 5′ upstream sequences, were amplified with the primers fum18_5F/fum18_compl_R and fum19_5F/fum19_compl_R (Table S1), respectively. For the generation of FUM19Kmut, the primer combinations fum19_5F/fum19_K631V_R, fum19_K631V_F/fum19_K1260V_R, and fum19_K1260V_F/fum19_compl_R were used. For FUM19Dmut, PCRs with the following primer pairs were performed: fum19_5F/fum19_D743K_R, fum19_D743K_F/fum19_D1397_R, and fum19_D1397K_F/fum19_compl_R. The nourseothricin resistance cassette, including TtrpC, was amplified from pZPnat1 with nat1_F/nat1_TtrpC_R. Furthermore, 3′ flanks of both genes were generated with fum18_compl_3F/fum18_3R and fum19_compl_3F/fum19_3R. As indicated above, complementation vectors were assembled by homologous recombination with the doubly digested plasmid backbone pYES2.

Primers used in this study. Introduced overhangs required for yeast recombinational cloning are underlined. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB (116KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

FUM19 overexpression was achieved by fusing the first 1.2 kb of the gene to the constitutive A. nidulans promoter PoliC. To this end, the insert was amplified with OE_fum19_F/OE_fum19_R (Table S1) and was cloned into NcoI/NotI-digested pNDH-OGG (57). FUM17::GFP was cloned under the control of the constitutive F. fujikuroi promoter Pgln1 by using the primer pair OE_fum17_F/fum17_GFP_R and the NcoI-digested vector backbone pNAH-GGT (37, 57). Similarly, FUM18::DsRed fusion driven by PoliC was achieved with the primer pair OE_fum18_F/fum18_DsRed_R and NcoI-digested pNDN-ODT (57). CER1::BFP fusion was obtained by amplifying the gene of interest with OE_cer1_F/cer1_BFP_R, PgpdA from pUC-hph with PgpdA_F/PgpdA_R, BFP from EBFP2-N1 (a gift from Michael Davidson, Addgene plasmid 54595) with BFP_F/BFP_Tgluc_R or BFP_F/BFP_Ttub_R, and subsequent cloning of these fragments into SpeI/NotI-restricted pNDH-OGG (hphR and Tgluc) or pNDN-ODT (natR and Ttub). DsRed::FUM8 under the control of PoliC was generated by using the primers fum8_DsRed_F/fum8_Ttub_R and pNDN-ODT linearized with NotI. Finally, FUM3::GFP under the control of PoliC was cloned using the primers OE_fum3_F/fum3_GFP_R and NcoI-digested pNDH-OGG. These F. verticillioides overexpression vectors can be found in Fig. S8A.

Promoter exchange of S. cerevisiae LAG1 with the inducible TETON promoter (Fig. S9) started out by amplifying upstream and (intragenic) downstream sequences with the primer pairs lag1_5F/lag1_5R and lag1_3F/lag1_3R (Table S1), respectively, based on BY4741 gDNA. The histidine HIS3 marker gene, including promoter and terminator sequences, was generated with his3_Prom_TET_F/his3_Term_R from gDNA of a prototrophic S. cerevisiae strain (Jena Microbial Research Collection, accession no. STI25222). TETON (59) was amplified with TET_F/TET_R, and the complete vector was assembled under the use of doubly digested pYES2 as indicated above.

Finally, ceramide synthase yeast complementation vectors were constructed (Fig. S9A) by amplification of the inserts with the primer combination Tef1_F/Cyc1T_R (Table S1) based on F. verticillioides cDNA, S. cerevisiae gDNA, or human HT29-MTX (33) cDNA. Coexpression of two genes from the same promoter was achieved by inserting the viral 2A sequence in between, yielding one large polycistronic mRNA that gives individual proteins upon cotranslational cleavage (59). To this end, double-stranded DNA was gained from the 2A_F/2A_R primer combination (Table S1) via boiling and subsequent annealing at room temperature. The ceramide synthase genes were expressed under the control of the constitutive yeast promoter Ptef1 by cloning the obtained fragments into the SmaI/PvuII-digested vector backbone pYES2::Ptef1 (59). All of the above-described expression vectors were verified by sequencing using primers listed in Table S1.

F. verticillioides transformation and analysis of transformants.

Protoplast transformation of F. verticillioides was carried out as described elsewhere (60). Transformants were selected on plates with 200 μg/ml hygromycin B (InvivoGen Europe, Toulouse, France) and/or 200 μg/ml nourseothricin (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany). Linear deletion and complementation constructs were transformed. Deletion fragments and FUM18C were amplified from the assembled vectors with primers 5F/3R (Table S1). For FUM19 complementation and point mutation, 40 μg of each vector was linearized with SpeI prior to transformation. Homologous recombination of the flanks and absence of untransformed nuclei were tested by diagnostic PCR, while Southern blot experiments excluded additional ectopic integration events. It was made sure that complemented strains were only able to grow on nourseothricin (complementation phenotype) but were unable to grow on hygromycin B (deletion phenotype). Two to four independent transformants were verified for Δfum17 (Fig. S5A), Δfum18 (Fig. S5B), FUM18C (Fig. S5C), Δfum17/18 (Fig. S6A), Δfum17-19 (Fig. S6B), Δfum19, FUM19C, FUM19Kmut, and FUM19Dmut (Fig. S7A), and Δfum21 and Δfum19/Δfum21 (Fig. S7B) mutants.

Verification of Δfum17/18 double and Δfum17-19 triple mutants by diagnostic PCR and Southern blot. (A) Deletion of FUM17/18 via homologous recombination with the hygromycin B resistance cassette (hphR). Diagnostic PCR verified the correct recombination of 5′ and 3′ flanks, and the absence of WT signal for three independent transformants. Genomic DNA of transformants and WT was digested with SalI, and the 3′ flank was applied for probing. Δfum17/18 T7 showed an ectopic integration and was not chosen for further analyses. (B) Deletion of FUM17-19 via homologous recombination with hphR. Genomic DNA was digested with SalI, and the 5′ flank was applied for probing. Δfum17-19 T4 showed an ectopic integration and was not chosen for further analyses. Download FIG S6, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Verification of FUM19 and FUM21 mutants by diagnostic PCR and Southern blot. (A) Deletion of FUM19 via homologous recombination with the hygromycin B resistance cassette (hphR) and subsequent complementation with the full-length (point-mutated) gene and nourseothricin resistance cassette (natR). Diagnostic PCR verified the correct recombination of 5′ and 3′ flanks, and the absence of untransformed nuclei for four independent Δfum19, FUM19C, FUM19Kmut, and FUM19Dmut mutants, respectively. Genomic DNA of transformants and WT was digested with BglII, and the 5′ flank was applied for probing. Δfum19 T29 showed an ectopic integration and was not chosen for further analyses. (B) Deletion of FUM21 in the WT and Δfum19 backgrounds via homologous recombination with natR. Genomic DNA was digested with XbaI, and the 5′ flank was applied for probing. Download FIG S7, PDF file, 2.8 MB (2.9MB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Verification of F. verticillioides overexpression strains by diagnostic PCR. (A) Vectors for constitutive expression of the first 1.2 kb of FUM19 (PoliC), as well as full-length fusion genes FUM17::GFP (Pgln1), FUM18::DsRed (PoliC), CER1::BFP (PgpdA), DsRed::FUM8 (PoliC), and FUM3::GFP (PoliC). (B to I) Diagnostic PCR verified the in locus integration of circular pOE::FUM191.2 kb, giving full-length FUM19, as well as the ectopic integration of the other circular vectors, yielding indicated single and double mutants. The tested PCR signals were absent in the WT control. Download FIG S8, PDF file, 1.9 MB (1.9MB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Ceramide synthase complemented yeast strains. (A) S. cerevisiae, F. verticillioides, and human ceramide synthase genes were expressed under control of the constitutive yeast promoter Ptef1. pYES2::Ptef1 was used for cloning and served as empty vector control. (B) Promoter exchange of S. cerevisiae LAG1 using the inducible TETON promoter and HIS3 marker gene. (C) S. cerevisiae Δlac1/TET::LAG1 strains, harboring the respective Ptef1 ceramide synthase plasmids (PCR Ptef1-Tcyc1), showed correct recombination of TET::LAG1 5′ flank, and absence of LAC1 WT signal (see Fig. 6A and C). (D) S. cerevisiae WT, Δlac1, and Δlag1 strains harboring Ptef1::FvCER3 (see Fig. 6B). (E) S. cerevisiae WT strain harboring Ptef1::FvCER1, Ptef1::FvCER2, and Ptef1::FUM18 (see Fig. 6D). Download FIG S9, PDF file, 2.1 MB (2.2MB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Furthermore, 20 to 40 μg of each circular vector was transformed to achieve overexpression of FUM19 as well as expression of tagged FUM17, FUM18, CER1, FUM8, and FUM3. Homologous integration of the vector to gain full-length FUM19 was verified for three independent OE::FUM19 mutants (Fig. S8B). In addition, diagnostic PCR verified the ectopic integration in two to three independent single or double mutants: OE::FUM17::GFP (Fig. S8C, E, F, and H), OE::FUM18::DsRed (Fig. S8D, E, and G), OE::CER1::BFP (Fig. S8F and G) OE::DsRed::FUM8 (Fig. S8H), and OE::FUM3::GFP (Fig. S8I).

Expression analysis via qRT-PCR.

Fungal strains were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln for 2 days, prior to harvest and lyophilization. RNA was isolated from ground mycelium under the use of TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Next, 1.5 μg of RNA was DNase I treated and transcribed into cDNA with a ProtoScript II first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt/Main, Germany) and included oligo(dT) primers according to the standard protocol. For qRT-PCR, MyTaq HS Mix (Biocat, Heidelberg, Germany) was used in combination with 5% (vol/vol) EvaGreen Dye (Biotium, Fremont, CA) and black nontranslucent plates (Applied Biosystems standard; 4titude, Ltd., Berlin, Germany). Reactions were run in an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 real-time PCR system and analyzed with QuantStudio design and analysis software (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). Expression of the genes of interest, as well as of the three constitutively expressed reference genes (FVEG_11477 encoding ubiquitin, FVEG_02524 encoding actin, FVEG_09003 encoding a GDP-mannose transporter) (37), was determined in triplicate with primers listed in Table S1. The annealing temperature was set to 60°C, and primer efficiencies were between 90 and 110%. Relative expression was calculated with the ΔΔCT method (61).

FB1 analysis via HPLC-HRMS.

For FB1 analysis, the strains were grown in ICI/6 mM Gln for 7 days. The supernatant was separated from the mycelium by filtration through Miracloth (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany), and then culture fluids were fully cleared by centrifugation and mixed with 1:1 (vol/vol) methanol and 1% (vol/vol) naringenin as an internal standard (1 mg/ml in methanol; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) to give 1 ml. For extraction of FB1 from washed and lyophilized mycelium, 0.1 g was extracted with 1.5 ml of ethyl acetate-methanol-dichlormethane (3:2:1, vol/vol) by vigorous shaking for 2 h (37). Then, 1 ml was evaporated to dryness, taken up in 1 ml of methanol with 1% (vol/vol) naringenin, and subjected to HPLC-HRMS after filtration through 0.2-μm PTFE filters (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany).

HPLC-HRMS measurements were conducted on a Thermo Fisher Q ExactivePlus hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer with an electrospray ion source operating in negative ionization mode with a full scan range of 100 to 1,000 m/z in combination with an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). The system was equipped with a Kinetex C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.5 μm, 100 Å; Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). The following elution gradient was used (solvent A, H2O plus 0.1% [vol/vol] HCOOH; solvent B, acetonitrile plus 0.1% [vol/vol] HCOOH): 5% B for 0.5 min, 5 to 97% B in 11.5 min, and 97% B for 3 min; flow rate of 0.3 ml/min; injection of 10 μl; and column oven at 40°C. Raw liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry data were analyzed using XCalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific). FB1 peak areas were normalized against the internal standard to account for variability between runs. FB1 levels were related to the dry weight of the cultures, which were performed in biological triplicate.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Homologs of ceramide synthase genes were retrieved by BLASTp and/or BLASTx analyses (62) of fungal genome sequence databases at NCBI and the Joint Genome Institute. Initially, the S. cerevisiae LAG1 and LAC1 genes and F. verticillioides FUM17, FUM18, CER1, CER2, and CER3 genes were used as query sequences. Subsequently, sequences from other fungal species were used to ensure that we obtained ceramide synthase sequences from diverse fungi. In some cases, gene sequences were manually annotated to correct obvious errors in automated predictions of translation start and stop sites and intron splice sites. Using BLAST, we retrieved the predicted amino acid sequences for 141 genes. We also retrieved a single homolog from both rat and human to use as an outgroup. The amino acid sequences were aligned with the MUSCLE algorithm as implemented in the program MEGA7 (63). The resulting alignment was then subjected to tree building analysis using the maximum-likelihood method as implemented in the program IQ-Tree (version 1.6.9) with ultrafast bootstrapping (64). The resulting tree was viewed and formatted with MEGA7.

Confocal microscopy.

Fungal hyphae were grown from 104 conidia in 300 μl of ICI/6 mM Gln as adherent cultures in ibidi dishes (ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany) at 30°C for 16 h. For nuclear staining, NucBlue Live ReadyProbes reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All microscopy experiments were performed on an Axio Observer Spinning Disc confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with the 63× or 100× oil objectives and analyzed with ZEN 2.6 software. Fluorescent stains and proteins were excited using the 405-, 488-, and 561-nm laser lines. Postprocessing of the images for brightness adjustments was done in ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov).

Yeast complementation assay.

The generated Δlac1/TET::LAG1 conditional null mutant was transformed with the ceramide synthase-containing complementation plasmids (Fig. S9A), and positive colonies were selected on synthetic defined medium lacking uracil (SD-Ura) plus 8 μg/ml doxycycline hyclate (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany). The empty vector pYES2::Ptef1 served as the control, as well as the progenitor S. cerevisiae BY4741 and Δlac1 strains (Euroscarf, Oberursel, Germany). At least two independent transformants were tested per strain, and verification of all strains by diagnostic PCR is summarized in Fig. S9C. For the drop assay, an overnight culture was prepared in 5 ml of SD–Ura plus 8 μg/ml doxycycline, which was shaken at 180 rpm and 30°C. Then, 10 μl of a 1:10 dilution series in water was spotted onto SD–Ura plates with or without doxycycline, starting with an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Growth was evaluated after 2 days at 30°C.

Resazurin cell viability assay.

FB1 growth inhibition of ceramide synthase-complemented yeast strains and F. verticillioides spores was evaluated via monitoring the reduction of resazurin to fluorescent resorufin every 30 min for up to 24 h. The experiments were conducted in a CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) with sterile black 96-well plates (BRANDplates; VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). Incubation was performed with SD–Ura at 30°C for yeast cells, while Fusarium spores were grown in the presence of ICI/6 mM Gln at 28°C. Each well contained 150 μl: 10 μl cells in medium (yeast, OD600 = 0.01; Fusarium, 5 × 104 spores/ml final concentration), 10 μl of FB1 in water (250 to 500 μg/ml final concentration; Biomol, Hamburg, Germany; lot 0542168) or 10 μl of water as control, and 1.5 μl of 0.002% (wt/vol) resazurin sodium salt in water (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany), adjusted to the final volume with medium. Resorufin was measured at the following wavelengths: excitation at 570 nm and emission at 615 nm (as previously performed) (30). Controls without cells did not show an increase in fluorescence. Measurements were done in biological triplicate, and fluorescence measurements of each sample were normalized against its lowest starting value. Growth inhibition was calculated by comparing fluorescence maxima between treated and nontreated samples (Fig. S4).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniela Hildebrandt for excellent technical assistance. Furthermore, we are grateful to Maria Joanna Niemiec and Ilse Jacobsen (Microbial Immunology, HKI Jena, Germany) for kindly providing HT29-MTX cell cultures.

This study was supported by the Leibniz Research Cluster in the frame of the BMBF Strategic Process Biotechnology 2020+ and by a grant of the European Social Fund ESF Europe for Thuringia projects SphinX and MiQWi.

We declare there are no competing interests. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author contributions were as follows: conceptualization, S.J. and V.V.; methodology, S.J., J.R., S.H., and V.V.; investigation, S.J., I.F., K.J., J.R., and F.H.; phylogeny, R.H.P.; writing (original draft), S.J.; writing (editing), R.H.P., F.H., and V.V.; writing (review), all authors; funding acquisition, R.H.P., F.H., and V.V.; and supervision, S.J. and V.V.

Footnotes

Citation Janevska S, Ferling I, Jojić K, Rautschek J, Hoefgen S, Proctor RH, Hillmann F, Valiante V. 2020. Self-protection against the sphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitor fumonisin B1 is conferred by a FUM cluster-encoded ceramide synthase. mBio 11:e00455-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00455-20.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venkatesh N, Keller NP. 2019. Mycotoxins in conversation with bacteria and fungi. Front Microbiol 10:403. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Netzker T, Fischer J, Weber J, Mattern DJ, König CC, Valiante V, Schroeckh V, Brakhage AA. 2015. Microbial communication leading to the activation of silent fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Front Microbiol 6:299. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Díaz C, Rahjoo V, Sulyok M, Ghionna V, Martín-Vicente A, Capilla J, Di Pietro A, López-Berges MS. 2018. Fusaric acid contributes to virulence of Fusarium oxysporum on plant and mammalian hosts. Mol Plant Pathol 19:440–453. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Studt L, Janevska S, Niehaus E, Burkhardt I, Arndt B, Sieber CMK, Humpf H, Dickschat JS, Tudzynski B. 2016. Two separate key enzymes and two pathway-specific transcription factors are involved in fusaric acid biosynthesis in Fusarium fujikuroi. Environ Microbiol 18:936–956. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nützmann H, Scazzocchio C, Osbourn A. 2018. Metabolic gene clusters in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet 52:159–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller NP. 2015. Translating biosynthetic gene clusters into fungal armor and weaponry. Nat Chem Biol 11:671–677. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khaldi N, Wolfe KH. 2011. Evolutionary origins of the fumonisin secondary metabolite gene cluster in Fusarium verticillioides and Aspergillus niger. Int J Evol Biol 2011:423821. doi: 10.4061/2011/423821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockmann-Juvala H, Savolainen K. 2008. A review of the toxic effects and mechanisms of action of fumonisin B1. Hum Exp Toxicol 27:799–809. doi: 10.1177/0960327108099525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riley RT, Wang E, Schroeder JJ, Smith ER, Plattner RD, Abbas H, Yoo HS, Merrill AH. 1996. Evidence for disruption of sphingolipid metabolism as a contributing factor in the toxicity and carcinogenicity of fumonisins. Nat Toxins 4:3–15. doi: 10.1002/19960401nt2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezuidenhout SC, Gelderblom WCA, Gorst-Allman CP, Horak RM, Marasas WFO, Spiteller G, Vleggaar R. 1988. Structure elucidation of the fumonisins, mycotoxins from Fusarium moniliforme. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun (Camb) 1988:743–745. doi: 10.1039/c39880000743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor RH, Brown DW, Plattner RD, Desjardins AE. 2003. Coexpression of 15 contiguous genes delineates a fumonisin biosynthetic gene cluster in Gibberella moniliformis. Fungal Genet Biol 38:237–249. doi: 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00525-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang E, Norred WP, Bacon CW, Riley RT, Merrill AH Jr.. 1991. Inhibition of sphingolipid biosynthesis by fumonisins: implications for diseases associated with Fusarium moniliforme. J Biol Chem 266:14486–14490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrill AH Jr, van Echten G, Wang E, Sandhoff K. 1993. Fumonisin B1 inhibits sphingosine (sphinganine) N-acyltransferase and de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in cultured neurons in situ. J Biol Chem 268:27299–27306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang E, Ross PF, Wilson TM, Riley RT, Merrill AH. 1992. Increases in serum sphingosine and sphinganine and decreases in complex sphingolipids in ponies given feed containing fumonisins, mycotoxins produced by Fusarium moniliforme. J Nutr 122:1706–1716. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.8.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbas HK, Tanaka T, Duke SO, Porter JK, Wray EM, Hodges L, Sessions AE, Wang E, Merrill AH, Riley RT. 1994. Fumonisin- and AAL-toxin-induced disruption of sphingolipid metabolism with accumulation of free sphingoid bases. Plant Physiol 106:1085–1093. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrill AH Jr, Sullards MC, Wang E, Voss KA, Riley RT. 2001. Sphingolipid metabolism: roles in signal transduction and disruption by fumonisins. Environ Health Perspect 109:283–289. doi: 10.2307/3435020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J, Park W, Futerman AH. 2014. Ceramide synthases as potential targets for therapeutic intervention in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1841:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tidhar R, Futerman AH. 2013. The complexity of sphingolipid biosynthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:2511–2518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narayan S, Head SR, Gilmartin TJ, Dean B, Thomas EA. 2009. Evidence for disruption of sphingolipid metabolism in schizophrenia. J Neurosci Res 87:278–288. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He X, Huang Y, Li B, Gong C, Schuchman EH. 2010. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 31:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DW, Butchko RAE, Busman M, Proctor RH. 2007. The Fusarium verticillioides FUM gene cluster encodes a Zn(II)2Cys6 protein that affects FUM gene expression and fumonisin production. Eukaryot Cell 6:1210–1218. doi: 10.1128/EC.00400-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butchko RAE, Plattner RD, Proctor RH. 2006. Deletion analysis of FUM genes involved in tricarballylic ester formation during fumonisin biosynthesis. J Agric Food Chem 54:9398–9404. doi: 10.1021/jf0617869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyser Z, Vismer HF, Klaasen JA, Snijman PW, Marasas WF. 1999. The antifungal effect of fumonisin B1 on Fusarium and other fungal species. S Afr J Sci 95:455–458. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung L, Wang IX, Nikaido K, Liu P, Ames GF, Kim S. 1998. Crystal structure of the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC transporter. Nature 396:703–707. doi: 10.1038/25393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shyamala V, Baichwal V, Beall E, Ames GF. 1991. Structure-function analysis of the histidine permease and comparison with cystic fibrosis mutations. J Biol Chem 266:18714–18719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winter E, Ponting CP. 2002. TRAM, LAG1 and CLN8: members of a novel family of lipid-sensing domains? Trends Biochem Sci 27:381–383. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barz WP, Walter P. 1999. Two endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane proteins that facilitate ER-to-Golgi transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. Mol Biol Cell 10:1043–1059. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang JC, Kirchman PA, Zagulski M, Hunt J, Jazwinski SM. 1998. Homologs of the yeast longevity gene LAG1 in Caenorhabditis elegans and human. Genome Res 8:1259–1272. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer V, Wanka F, van Gent J, Arentshorst M, van den Hondel C, Ram A. 2011. Fungal gene expression on demand: an inducible, tunable, and metabolism-independent expression system for Aspergillus niger. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2975–2983. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02740-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monteiro MC, De La Cruz M, Cantizani J, Moreno C, Tormo JR, Mellado E, De Lucas JR, Asensio F, Valiante V, Brakhage AA, Latgé J, Genilloud O, Vicente F. 2012. A new approach to drug discovery: high-throughput screening of microbial natural extracts against Aspergillus fumigatus using resazurin. J Biomol Screen 17:542–549. doi: 10.1177/1087057111433459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Brien J, Wilson I, Orton T, Pognan F. 2000. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem 267:5421–5426. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariscal A, Lopez-Gigosos RM, Carnero-Varo M, Fernandez-Crehuet J. 2009. Fluorescent assay based on resazurin for detection of activity of disinfectants against bacterial biofilm. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:773–783. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1879-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesuffleur T, Barbat A, Dussaulx E, Zweibaum A. 1990. Growth adaptation to methotrexate of HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells is associated with their ability to differentiate into columnar absorptive and mucus-secreting cells. Cancer Res 50:6334–6343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim FY, Keller NP. 2014. Spatial and temporal control of fungal natural product synthesis. Nat Prod Rep 31:1277–1286. doi: 10.1039/c4np00083h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanada K, Kumagai K, Tomishige N, Kawano M. 2007. CERT and intracellular trafficking of ceramide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1771:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmelz EM, Dombrink-Kurtzman MA, Roberts PC, Kozutsumi Y, Kawasaki T, Merrill AH. 1998. Induction of apoptosis by fumonisin B1 in HT29 cells is mediated by the accumulation of endogenous free sphingoid bases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 148:252–260. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janevska S, Arndt B, Niehaus E, Burkhardt I, Rösler SM, Brock NL, Humpf H, Dickschat JS, Tudzynski B. 2016. Gibepyrone biosynthesis in the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi is facilitated by a small polyketide synthase gene cluster. J Biol Chem 291:27403–27420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.753053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niehaus E, Studt L, von Bargen KW, Kummer W, Humpf H, Reuter G, Tudzynski B. 2016. Sound of silence: the beauvericin cluster in Fusarium fujikuroi is controlled by cluster-specific and global regulators mediated by H3K27 modification. Environ Microbiol 18:4282–4302. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gardiner DM, Jarvis RS, Howlett BJ. 2005. The ABC transporter gene in the sirodesmin biosynthetic gene cluster of Leptosphaeria maculans is not essential for sirodesmin production but facilitates self-protection. Fungal Genet Biol 42:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amnuaykanjanasin A, Daub ME. 2009. The ABC transporter ATR1 is necessary for efflux of the toxin cercosporin in the fungus Cercospora nicotianae. Fungal Genet Biol 46:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choquer M, Lee M, Bau H, Chung K. 2007. Deletion of a MFS transporter-like gene in Cercospora nicotianae reduces cercosporin toxin accumulation and fungal virulence. FEBS Lett 581:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiemann P, Willmann A, Straeten M, Kleigrewe K, Beyer M, Humpf H, Tudzynski B. 2009. Biosynthesis of the red pigment bikaverin in Fusarium fujikuroi: genes, their function and regulation. Mol Microbiol 72:931–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallée B, Riezman H. 2005. Lip1p: a novel subunit of acyl-CoA ceramide synthase. EMBO J 24:730–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuge T, Harimoto Y, Akimitsu K, Ohtani K, Kodama M, Akagi Y, Egusa M, Yamamoto M, Otani H. 2013. Host-selective toxins produced by the plant pathogenic fungus Alternaria alternata. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:44–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kheder AA, Akagis Y, Tsuge T, Kodama M. 2012. Functional analysis of the ceramide synthase gene ALT7, a homolog of the disease resistance gene Asc1, in the plant pathogen Alternaria alternata. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 01:001. doi: 10.4172/2157-7471.S2-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rösler SM, Sieber CMK, Humpf H, Tudzynski B. 2016. Interplay between pathway-specific and global regulation of the fumonisin gene cluster in the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:5869–5882. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spassieva SD, Markham JE, Hille J. 2002. The plant disease resistance gene Asc-1 prevents disruption of sphingolipid metabolism during AAL-toxin-induced programmed cell death. Plant J 32:561–572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandwagt BF, Mesbah LA, Takken FLW, Laurent PL, Kneppers TJA, Hille J, Nijkamp H. 2000. A longevity assurance gene homolog of tomato mediates resistance to Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici toxins and fumonisin B1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:4961–4966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S, Du L, Yuen G, Harris SD. 2006. Distinct ceramide synthases regulate polarized growth in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Biol Cell 17:1218–1227. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-06-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandes CM, Goldman GH, Del Poeta M. 2018. Biological roles played by sphingolipids in dimorphic and filamentous fungi. mBio 9:e00642-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00642-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rittenour WR, Chen M, Cahoon EB, Harris SD. 2011. Control of glucosylceramide production and morphogenesis by the Bar1 ceramide synthase in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS One 6:e19385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leslie JF, Doe FJ, Plattner RD, Shackelford DD, Jonz J. 1992. Fumonisin B1 production and vegetative compatibility of strains from Gibberella fujikuroi mating population “A” (Fusarium moniliforme). Mycopathologia 117:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00497277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontecorvo G, Roper JA, Hemmons LM, Macdonald KD, Bufton AWJ. 1953. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet 5:141–238. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Darken MA, Jensen AL, Shu P. 1959. Production of gibberellic acid by fermentation. Appl Microbiol 7:301–303. doi: 10.1128/AEM.7.5.301-303.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geissman TA, Verbiscar AJ, Phinney BO, Cragg G. 1966. Studies on the biosynthesis of gibberellins from (–)-kaurenoic acid in cultures of Gibberella fujikuroi. Phytochemistry 5:933–947. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)82790-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colot HV, Park G, Turner GE, Ringelberg C, Crew CM, Litvinkova L, Weiss RL, Borkovich KA, Dunlap JC. 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:10352–10357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schumacher J. 2012. Tools for Botrytis cinerea: new expression vectors make the gray mold fungus more accessible to cell biology approaches. Fungal Genet Biol 49:483–497. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liebmann B, Müller M, Braun A, Brakhage AA. 2004. The cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A network regulates development and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun 72:5193–5203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5193-5203.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoefgen S, Lin J, Fricke J, Stroe MC, Mattern DJ, Kufs JE, Hortschansky P, Brakhage AA, Hoffmeister D, Valiante V. 2018. Facile assembly and fluorescence-based screening method for heterologous expression of biosynthetic pathways in fungi. Metab Eng 48:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tudzynski B, Homann V, Feng B, Marzluf GA. 1999. Isolation, characterization and disruption of the areA nitrogen regulatory gene of Gibberella fujikuroi. Mol Gen Genet 261:106–114. doi: 10.1007/s004380050947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Z, Schäffer AA, Miller W, Madden TL, Lipman DJ, Koonin EV, Altschul SF. 1998. Protein sequence similarity searches using patterns as seeds. Nucleic Acids Res 26:3986–3990. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials