Microbiome-associated bacteria can have diverse effects on health of their hosts, yet the genetic and molecular bases of these effects have largely remained elusive. This work demonstrates that a novel bacterial locus can modulate systemic plant immunity. Additionally, this work demonstrates that growth-promoting strains may have unanticipated consequences for plant immunity, and this is critical to consider when the plant microbiome is being engineered for agronomic improvement.

KEYWORDS: rhizosphere, microbiome, induced systemic susceptibility, Pseudomonas, Arabidopsis

ABSTRACT

Plant root-associated microbes promote plant growth and elicit induced systemic resistance (ISR) to foliar pathogens. In an attempt to find novel growth-promoting and ISR-inducing strains, we previously identified strains of root-associated Pseudomonas spp. that promote plant growth but unexpectedly elicited induced systemic susceptibility (ISS) rather than ISR to foliar pathogens. Here, we demonstrate that the ISS-inducing phenotype is common among root-associated Pseudomonas spp. Using comparative genomics, we identified a single Pseudomonas fluorescens locus that is unique to ISS strains. We generated a clean deletion of the 11-gene ISS locus and found that it is necessary for the ISS phenotype. Although the functions of the predicted genes in the locus are not apparent based on similarity to genes of known function, the ISS locus is present in diverse bacteria, and a subset of the genes were previously implicated in pathogenesis in animals. Collectively, these data show that a single bacterial locus contributes to modulation of systemic plant immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Plant growth promotion by beneficial microbes has long been of interest because of the potential to improve crop yields. Individual root-associated microbial strains can promote plant growth by facilitating nutrient uptake, producing plant hormones, or improving resilience to both abiotic and biotic stresses (1). In some cases, single bacterial loci underlie beneficial effects of microbes on plants, while other traits appear to be complex and polygenic.

Pseudomonas fluorescens and related species are a model for beneficial host-associated microbes due to their genetic tractability and robust host association across diverse eukaryotic hosts. Direct plant growth promotion (PGP) by Pseudomonas spp. can be mediated by bacterial production of the phytohormone auxin (2) or by the expression of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase, which metabolizes plant-derived ethylene (1, 3). Indirect PGP through antimicrobial activity and pathogen suppression has been attributed to production of the antibiotic 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) (4). However, the molecular basis of many traits, such as induced systemic resistance (ISR), has remained elusive, and multiple distinct bacterial traits, including production of siderophores, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and salicylic acid, have all been implicated (5).

We previously reported two Pseudomonas spp. that elicit induced systemic susceptibility (ISS) on Arabidopsis and can promote growth under nutrient-limiting conditions (6, 7). These Pseudomonas strains suppress a subset of salicylic acid (SA)-dependent responses and promote resistance to herbivores (7). Although it is possible that ISS-inducing strains contain multiple genetic loci that affect plant growth and pathogen resistance, we hypothesized that a single bacterial trait may be responsible for both the growth and immunity phenotypes of ISS strains. Growth and immunity have a reciprocal relationship in plants, leading to growth-defense tradeoffs to the extent that plant stunting has been used as a proxy for autoimmunity (8). As a result, we hypothesized that suppression of plant immunity by Pseudomonas strains that trigger ISS may be a consequence of PGP activity. The genomes of ISS strains do not contain genes for the ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate) deaminase enzyme prevalent in other Pseudomonas PGP strains (3); thus, we hypothesized that there may be a distinct mechanism of growth promotion in these strains.

Because of the high density of sampling and genome sequencing within P. fluorescens and related species, we reasoned that if ISS is an overlooked consequence of growth promotion, then (i) we should be able to identify additional ISS strains by sampling known PGP strains and additional root-associated strains, and (ii) assuming that a single unique locus was responsible, a comparative genomics approach should reveal the underlying genetic basis of ISS.

Here, we report that ISS is relatively common among Pseudomonas strains within the P. fluorescens species complex. We identified new ISS isolates, including previously described PGP or environmental isolates and new isolates from Arabidopsis roots. Using comparative genomics, we identified a single bacterial locus that is unique to Pseudomonas ISS strains. We show that the putative ISS locus is necessary to elicit ISS. While the function of genes in the locus remains elusive, a subset have previously been implicated in pathogenesis, and we found that the locus contributes to rhizosphere growth. Collectively, these data indicate that a single microbial locus contributes to a systemic immune response in a plant host.

RESULTS

ISS is a common feature of growth-promoting Pseudomonas spp.

We previously reported that two strains of Pseudomonas (CH229 and CH267) elicit induced systemic susceptibility (ISS) to the foliar pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 under conditions where a well-characterized ISR strain (Pseudomonas simiae WCS417 [9]) conferred resistance to P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (6, 7). To the best of our knowledge, descriptions of Pseudomonas-elicited ISS against bacterial pathogens are limited to Pseudomonas sp. strains CH229 and CH267, which were independently isolated from the rhizospheres of wild Arabidopsis plants in Massachusetts (USA). We reasoned that if ISS is common among Arabidopsis-associated Pseudomonas spp., we would be able to identify additional ISS strains from roots of Arabidopsis plants growing at distinct sites.

We isolated 25 new fluorescent pseudomonads from wild-growing Arabidopsis plants from additional sites in Massachusetts and in Vancouver, Canada. We generated ∼800-bp sequences of a region of the 16S rRNA gene where strains CH229 and CH267 are 99.5% identical, but each has only <96% identity to the well-characterized ISR strain WCS417. Reasoning that new ISS strains would be closely related to CH267 and CH229, we selected 3 new isolates (1 from Massachusetts [CH235] and 2 from British Columbia [PB101 and PB106]) that were >97% identical to CH267 by 16S rRNA sequencing and another 3 (from British Columbia; PB100, PB105, and PB120) that were <97% identical to CH229 and CH267 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We tested these 6 new rhizosphere Pseudomonas isolates for their ability to trigger ISS.

Correlation matrix of 16S rRNA similarity of new Pseudomonas isolates from the Arabidopsis rhizosphere. Isolates were selected based on similarity (>97% identical by partial 16S rRNA) to CH267 (CH235, PB101, and PB106) or distance (<97% identity by partial 16S rRNA) to CH267 (PB120, PB100, PB105). Isolates from the rhizosphere of Arabidopsis plants growing in Massachusetts, USA (*), or British Columbia, Canada (#). Download FIG S1, EPS file, 2.1 MB (2.2MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

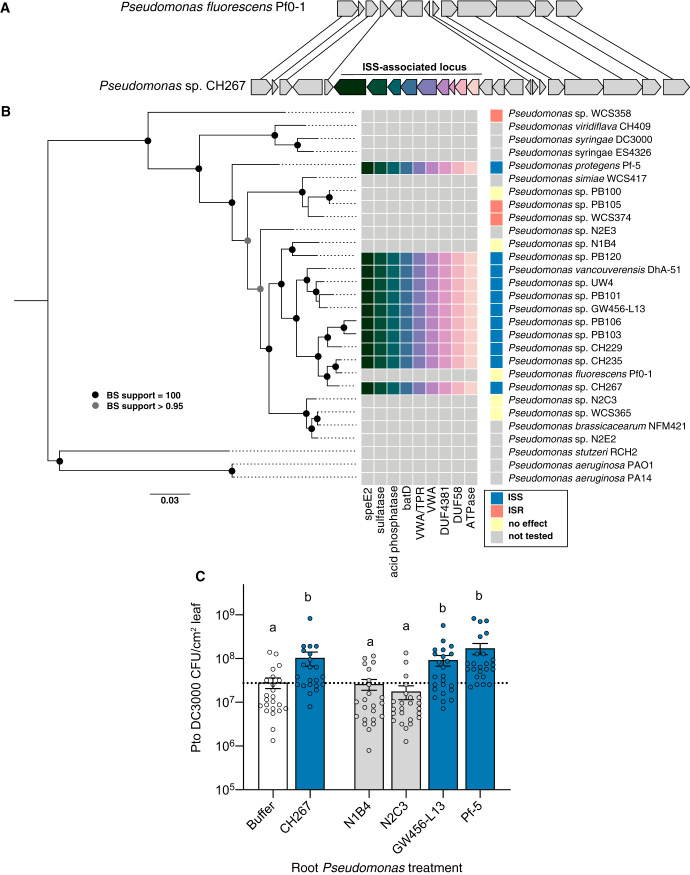

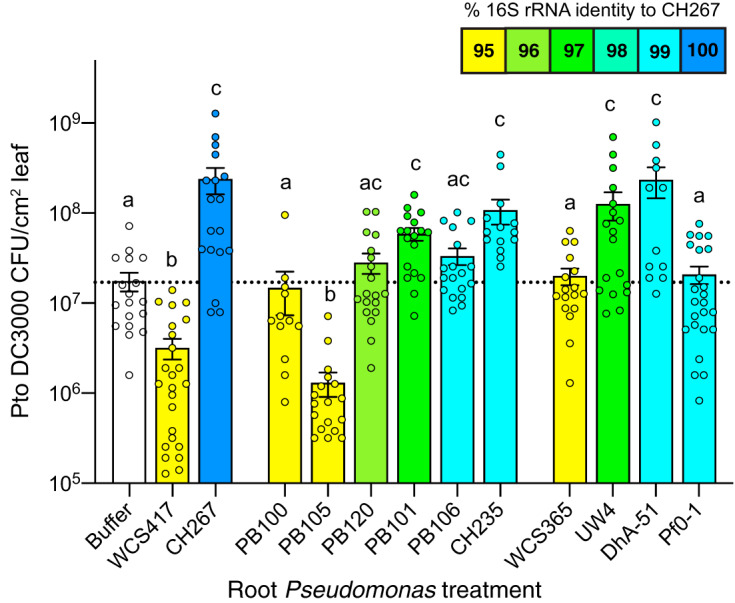

Consistent with the hypothesis that ISS may be common among closely related PGP Pseudomonas strains, we found that 2 of the 3 strains that were most closely related to CH267 (CH235 and PB101) elicited ISS (Fig. 1). Two strains with <96% identity to CH267 failed to trigger ISS: PB105 triggered ISR, and PB100 had no effect on systemic defenses (Fig. 1). PB106 and PB120 consistently enhanced susceptibility in all experiments, but to a more moderate degree (P < 0.1). Collectively, these data indicate that the ability to elicit ISS on Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 may be a common feature among some, but not all, closely related strains of Pseudomonas spp. isolated from the Arabidopsis rhizosphere.

FIG 1.

Induced systemic susceptibility (ISS) is common among closely related strains of Pseudomonas spp. Isolates of Pseudomonas were tested for their ability to modulate systemic defenses; bars are colored to indicate percent relatedness to CH267 by partial 16S rRNA sequence, as indicated in the key. Data are averages for 3 to 5 biological replicates, with 2 leaves from each of 3 plants (n = 6) per experiment. Means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) are shown. Letters designate levels of significance (P < 0.05) by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests.

Because ISS seemed restricted to strains that were closely related to CH267, we obtained several additional isolates with similar 16S rRNA sequences, including Pseudomonas sp. strain UW4, Pseudomonas sp. strain Pf0-1, and Pseudomonas vancouverensis strain DhA-51. We also tested a growth-promoting strain, Pseudomonas sp. strain WCS365, that is more distantly related and to our knowledge has not been tested for ISR/ISS (Table 1). We found that UW4 and DhA-51 elicited ISS, while Pf0-1 and WCS365 did not (Fig. 1). Pseudomonas sp. strains UW4 (10) and WCS365 are well-characterized growth-promoting strains. Pseudomonas sp. strain Pf0-1 (11) is an environmental isolate. Pseudomonas vancouverensis strain DhA-51 is also an environmental isolate (12) and was previously shown to be closely related to Pf0-1 (13). Because DhA-51 is an environmental isolate that triggers ISS, these data show that the ability to trigger ISS is not specific to rhizosphere isolates.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Genus and species | Source | Location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH267 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Cambridge, MA, USA | 6 |

| CH235 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Carlisle, MA, USA | 6 |

| CH229 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Carlisle, MA, USA | 6 |

| PB100 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Vancouver, BC, Canada | This study |

| PB101 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Vancouver, BC, Canada | This study |

| PB105 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Vancouver, BC, Canada | This study |

| PB106 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Vancouver, BC, Canada | This study |

| PB120 | Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis rhizosphere | Eastham, MA, USA | This study |

| WCS417 | P. simiae | Wheat rhizosphere | Netherlands | 30 |

| UW4 | Pseudomonas sp. | Reeds | Waterloo, ON, Canada | 10 |

| Pf0-1 | Pseudomonas sp. | Environmental soil | 11 | |

| DhA-51 | P. vancouverensis | Environmental soil | Vancouver, BC, Canada | 12 |

| WCS365 | Pseudomonas sp. | Tomato rhizosphere | Netherlands | 31 |

| Pf-5 | Pseudomonas sp. | Cotton rhizosphere | College Station, TX, USA | 32 |

| GW456-L13 | P. fluorescens | Groundwater | Oakridge, TN, USA | 33 |

| FW300-N1B4 | P. fluorescens | Groundwater | Oakridge, TN, USA | 33 |

| FW300-N2C3 | P. fluorescens | Groundwater | Oakridge, TN, USA | 33 |

To gain insights into the distinguishing features of ISS strains, we sequenced the genomes of the 6 new isolates (CH235, PB100, PB101, PB105, PB106, and PB120) from Arabidopsis roots as well as P. vancouverensis DhA-51 (UW4, WCS365, CH267, and CH229 had been sequenced previously). Whole-genome sequencing was used to assemble draft genomes (see Materials and Methods). We generated a phylogenetic tree using 122 conserved genes as described previously (7, 14). We found that all ISS strains are closely related to one another and fall within a monophyletic group which corresponds to the Pseudomonas koreensis, P. jessenii, and P. mandelii subgroups of P. fluorescens identified in a recent phylogenomic survey of Pseudomonas spp. (Fig. 2B) (15). However, not every isolate in this clade is an ISS strain; notably, Pf0-1, which has no effect on systemic immunity despite being closely related to CH229, is not an ISS strain. We reasoned that the absence of the ISS phenotype in Pf0-1 should facilitate the use of comparative genomics by allowing us to separate the phylogenetic signature from the phenotypic signature of ISS strains.

FIG 2.

The presence of a genomic island is predictive of the ISS phenotype. (A) A genomic island identified through comparative genomics is present in the ISS strains CH229, CH235, CH267, and UW4 and absent in Pf0-1 (no effect on systemic defense) and WCS417 (ISR strain). (B) Phylogenetic tree based on 122 core Pseudomonas genes. Genome sequencing of new strains shows that the island is present in strains that enhance susceptibility but not in those that trigger ISR or have no effect. (C) Two strains with the island (GW456-L13 and Pf-5) and two without (N1B4 and N2C3) were tested for ISS/ISR. Only those with the island significantly enhanced susceptibility. Data are averages for 3 biological replicates, with 2 leaves from each of 4 plants (n = 8) per experiment. Means ± SEM are shown. Letters indicate P < 0.05 by ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test.

Eleven genes in a single genomic locus are unique to ISS strains and predict ISS.

To identify the potential genetic basis of the ISS phenotype, we used a previously described database of orthologous genes for Pseudomonas spp. (14) to identify genes that are present in ISS strains (CH229, CH235, CH267, and UW4) but are absent in the closely related strain that has no effect on systemic defenses (Pf0-1). We used only the ISS strains with the most robust phenotypes for this analysis. We identified 29 predicted protein-coding genes that were absent in Pf0-1 but present in all of the other strains. Of these, 12 were small (<100 amino acids [aa]) hypothetical proteins. The remaining 17 predicted protein-coding genes were prioritized for further analysis and are shown in Table S1. Intriguingly, 11 of the 17 ISS unique genes are found in a single genomic locus.

Unique loci identified in comparative genomics. The genome content of 4 ISS strains (CH267, CH235, UW4, and CH229) was compared with that of the closely related non-ISS strain Pf0-1. Seventeen predicted protein-coding genes were identified. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (11.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

We surveyed the genomes of other Pseudomonas strains tested for ISS to determine if the presence of the 17 genes identified by our comparative genomics approach correlated with the ISS phenotype. We found that the 11 clustered genes were present in ISS strains (DhA-51 and PB101) and the strains with intermediate phenotypes (PB120 and PB106) but were absent in the non-ISS strains WCS365, WCS417, and PB105 (Fig. S2). The remaining 6 genes were all present in WCS365 and/or other non-ISS strains (Fig. S2). We chose to focus on the 11 ISS-unique genes (referred to here as “ISS locus”) for further study.

Distribution of loci identified by comparative genomics ISS loci across Pseudomonas strains. Comparative genomics between ISS strains UW4, CH229, CH235, and CH267 (black arrows) and non-ISS strain Pf0-1 (red arrow) identified 17 predicted protein-coding genes of >100 aa that were absent in Pf0-1 and present in strains that induce ISS. Eleven of these genes were found in a single genomic locus (box) and were absent in the non-ISS strain WCS365. Download FIG S2, EPS file, 1.7 MB (1.7MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

We found that the 11 genes in the ISS locus are found at a single genomic locus in all 4 of the ISS strains (Fig. 2A; also, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The flanking regions are conserved in the non-ISS strain Pf0-1 (Fig. 2A), indicating a recent insertion or deletion event. Within this locus, there is a single gene that is conserved in Pf0-1 in addition to two genes that are unique to each individual strain, suggesting multiple changes to this genomic region in recent evolutionary history. While all 11 genes are within the same genomic region in the ISS strains, the variability of this locus between closely related strains suggests that it may be rapidly evolving.

The ISS locus is highly variable between closely related strains. The 11 genes in the ISS locus are present in the ISS strains Pf0-1, CH235, CH267, and CH299 but absent in Pf0-1. Genes in the ISS locus are colored as in the key at the bottom of the figure and in Fig. 2. Conserved genes not unique to the ISS strains are colored similarly among strains; genes in gray are not conserved between strains at this locus. In CH229, Pf0-1, and CH267 the genes flanking the ISS locus are conserved in the same orientation, suggesting a recent insertion or deletion event. Download FIG S3, EPS file, 1.2 MB (1.3MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

We surveyed the genomes of sequenced isolates available in our collection for the presence of the ISS locus. We found a number of closely related strains from various environmental sources that contained the ISS locus, as well as a more distantly related strain (Pf-5) (Fig. 2B). We tested 2 strains that contain the ISS locus (Pf-5 and GW456-L13) as well as 2 that do not (FW300-N1B4 and FW300-N2C3) and found that the presence of the ISS locus correlated with the ISS phenotype, including the distantly related strain Pf-5 (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these data show that the presence of the 11 candidate genes in the ISS locus identified by our comparative genomics approach is predictive of the ISS phenotype.

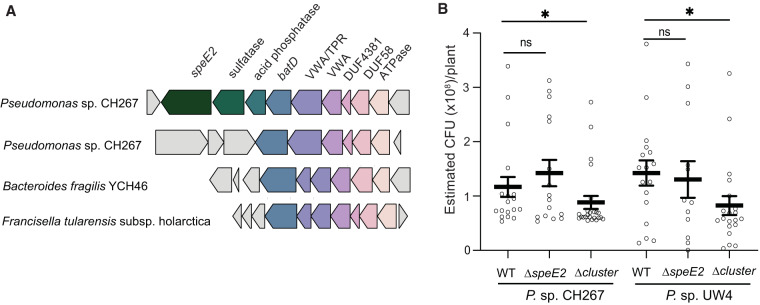

The ISS locus is necessary for ISS.

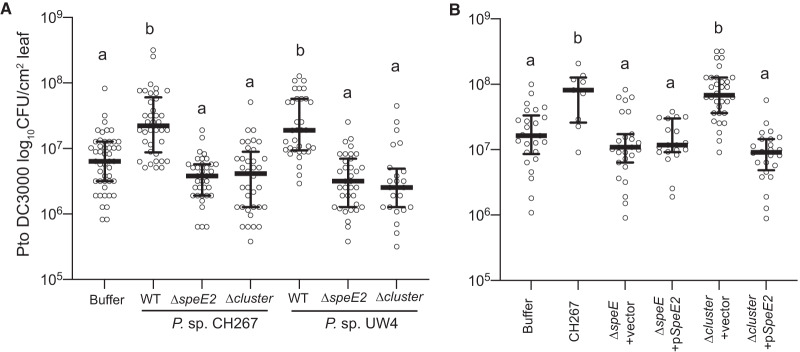

To test if the ISS locus is necessary for ISS strains to induce systemic susceptibility, we deleted the entire 15-kb locus, including the region spanning the 11 genes identified in our initial comparative genomics screen in strains CH267 and UW4 (Fig. 2A). We tested these deletion mutants for their ability to induce systemic susceptibility and found that deletion of the entire 11-gene locus (ΔISSlocus) resulted in a loss of the ISS phenotype in both CH267 and UW4 (Fig. 3A). This indicates that the ISS locus is necessary for ISS.

FIG 3.

The ISS locus and speE2 gene are necessary for ISS. (A) The speE2 gene and the entire 11-gene locus were deleted from CH267 and UW4. (B) Expression of speE2 from a plasmid is sufficient to complement the CH267 ∆speE2 mutant but not the ∆ISSlocus mutant. (A and B) Data are averages for 3 biological replicates, with 2 leaves from each of 4 plants (n = 8) per experiment. Means ± SEM are shown. Letters indicate P < 0.05 by ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD.

The functions of the majority of the genes in the ISS locus are not apparent based on similarity to genes of known function. A predicted 2,544-bp gene was annotated in the CH267 genome and others as speE2 due to the similarity of the predicted C terminus to that of the well-characterized spermidine synthase gene speE1 (PputUW4_02826 and CP336_12795 in UW4 and CH267, respectively). CH267 speE2 has similarity to the characterized spermidine synthase gene speE in P. aeruginosa (25% predicted amino acid identity to P. aeruginosa PA1687 [16]). A second speE-like gene in the genomes of UW4 and CH267, annotated as speE1, is outside the ISS locus (PputUW4_03691 and CP336_28780 in UW4 and CH267, respectively) and is highly similar to the P. aeruginosa speE gene (∼84.0% predicted amino acid identity) (16).

To test if the speE2 gene is necessary for ISS, we also constructed an in-frame deletion of just the speE2 gene in both CH267 and UW4. We found that deletion of speE2 abolished the ISS phenotype in both CH267 and UW4 (Fig. 3A). To determine if speE2 is the only gene within the ISS locus that is necessary for induction of ISS, we generated a complementation plasmid where the CH267 speE2 gene is expressed under the control of the lac promoter (plac-speE2). We introduced this plasmid into the ΔspeE2 deletion and ΔISSlocus deletions in CH267. While plac-speE2 complemented the CH267 ΔspeE2 deletion, it failed to complement the ΔISSlocus deletion (Fig. 3B), indicating that speE2 is not the only gene within the ISS locus that is required for ISS.

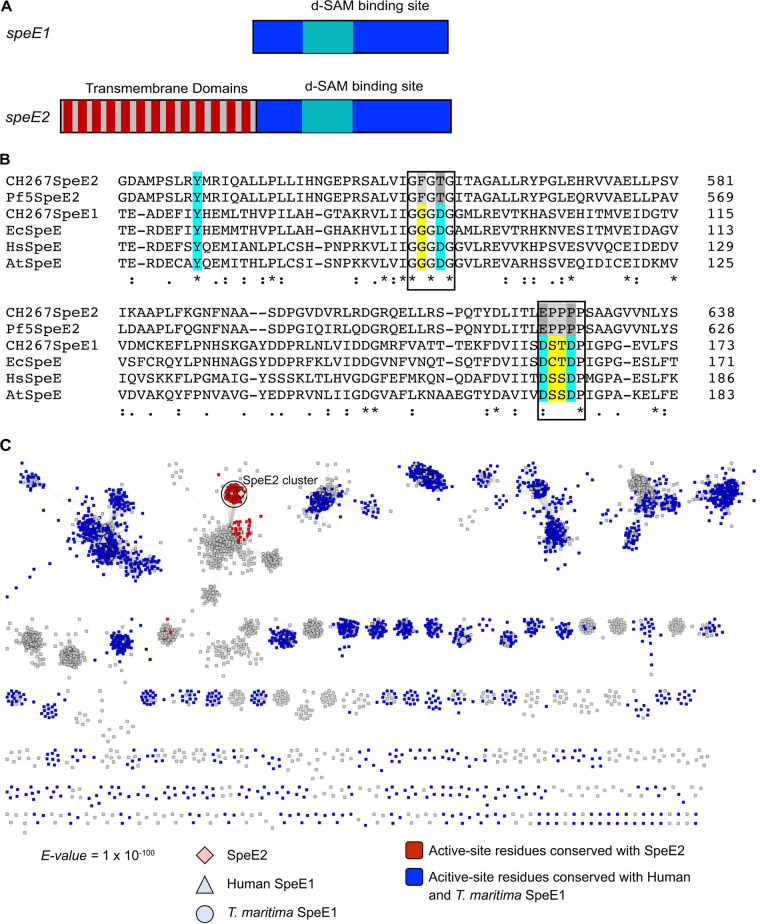

Because deletion of speE2 in CH267 and UW4 results in the specific loss of the ISS phenotype, the speE1 and speE2 genes are not functionally redundant. speE1 and speE2 differ in length and predicted structure (Fig. 4A). speE1 encodes a predicted 384-amino-acid protein and contains a predicted polyamine synthase domain with a predicted decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dSAM) binding motif. speE2 encodes a protein predicted to have 847 amino acids. Similar to speE1, the C terminus of the speE2 product contains a predicted dSAM-binding domain; however, the product of speE2 contains predicted transmembrane domains at its N terminus (Fig. 4A). Spermidine synthases generate spermidine by transferring the aminopropyl group of dSAM to putrescine. Previous structural and mutagenesis analysis on human and Thermatoga maritima SpeE1 enzymes revealed common residues important for catalysis (D276, D279, D201, and Y177 in human SpeE1 and the corresponding residues D173, D176, D101, and Y76 in T. maritima SpeE1) (17, 18). The catalytic mechanism was proposed to be initiated by the deprotonation of the putrescine amino group by the conserved aspartic acid D276 or D173 with the aid of the side chains of D201 or D101 and Y177 or Y76 as well as the main-chain carbonyl of L277 or S174, setting up a nucleophilic attack on dSAM. In addition, residue D279 or D176 is thought to play a role in substrate binding (17, 18).

FIG 4.

speE2 is different from characterized spermidine synthase genes. (A) The genome of CH267 contains two speE homologues. Both contain predicted dSAM binding domains and a spermidine synthase domain. Only SpeE2 contains predicted N-terminal transmembrane domains. (B) Multiple-sequence alignment of predicted amino acid sequence of CH267 SpeE2 and the relatively distantly related Pf-5 SpeE2 gene along with SpeE1-like proteins from CH267, E. coli, Homo sapiens, and Arabidopsis thaliana. Although the catalytic (blue) and binding site (yellow) residues are conserved in all SpeE1 homologues, both SpeE2 genes have changes in these regions (gray). (C) Sequence similarity network (SSN) of SpeE2 and protein sequences found with the PFAM domain code PF17284. Sequences that have the conserved residues D201/D101, D276/D173, and D279/D176 similar to the human and T. maritima SpeE1 are blue, while sequences that had conserved residues T556, E624, and P627 similar to SpeE2 are red. Clusters with only 1 sequence were removed for simplicity.

To determine if SpeE2 has the potential to be a spermidine synthase, we performed an amino acid sequence alignment to see if the catalytic residues from classic spermidine synthases are conserved in SpeE2. We found that although the tyrosine residue is conserved, SpeE2 consists of different residues at the corresponding aspartic acid positions. The proposed catalytic residue D276 or D173 in the human and T. maritima enzymes corresponds to E624 in SpeE2, while residues D201 or D101 and D279 or D176 have been converted to T556 and P627 (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we generated a sequence similarity network for SpeE2 with enzymes found in the PF17284 protein family and found that SpeE2 belongs to a distinct cluster away from any functionally characterized enzymes (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the SpeE2 active-site residue substitutions are almost completely conserved within and unique to the SpeE2 cluster (Fig. 4C), suggesting that while Pseudomonas sp. strain CH267 SpeE2 is unlikely to act as a spermidine synthase, it may have a distinct function.

Additional roles for the ISS locus in host interactions.

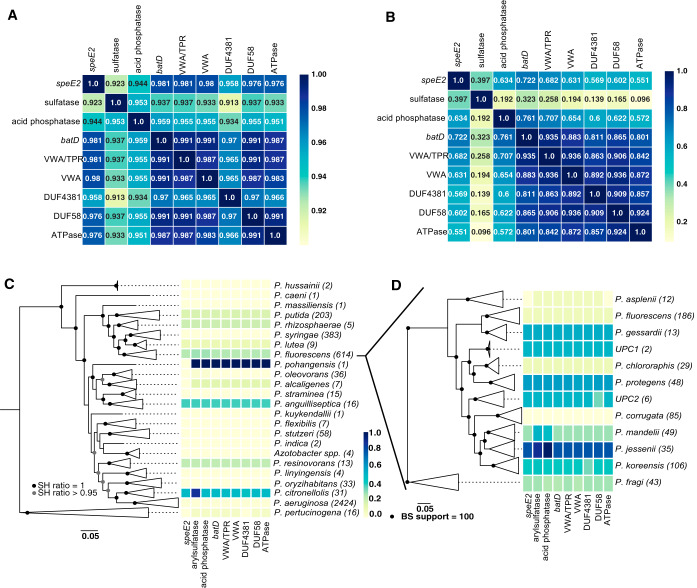

While speE2 is necessary for ISS, the failure of ΔspeE2 to complement the 11-gene ISS locus deletion (Fig. 3C) indicates that at least one other gene in the ISS locus is likely required for ISS. We tested whether speE2 is always associated with the same larger locus across the genus Pseudomonas. When we analyzed our entire computational data set of >3,800 genomes from across Pseudomonas, we found that there was a strong correlation for the presence or absence of 9 of 11 genes (r > 0.9) (Fig. 5A). Moreover, these 9 co-occurring genes were frequently found in the same genomic region, as there were moderate to strong correlations for 9 of the 11 genes co-occurring in the same 50-kb genomic region (Fig. 5B). From a phylogenomic standpoint, we found that these genes were broadly distributed throughout the genus Pseudomonas and co-occurred even in taxonomic groups far outside the P. fluorescens clade (Fig. 5C). Within the P. fluorescens clade, the ISS locus genes are frequently found in some clades, such as the P. koreensis and P. jessenii clades, which contain most of our isolates (Fig. 5D). However, some clades are missing these genes entirely, such as the plant-associated Pseudomonas corrugata clade (Fig. 5D). Together, these genomic data indicate that despite their polyphyletic distribution among divergent clades of Pseudomonas spp., the genes in the ISS locus likely participate in conserved or similar functions.

FIG 5.

Nine genes in the ISS locus nearly always co-occur and are present across the genus Pseudomonas. (A) Correlation coefficient matrix for 9 genes in the ISS locus across all 3,886 Pseudomonas genomes in the comparative genomics database. (B) Correlation coefficient matrix for the 9 ISS genes across every 50-kb genomic region that contains at least one of the 9 genes. (C) Distribution of the 9 ISS genes across subclades of the Pseudomonas genus. (D) Distribution of the 9 ISS genes within subclades of the P. fluorescens group.

Within the 9 genes that have a high frequency of co-occurrence, we identified a 6-gene predicted operon in the ISS locus with identical domain structure and organization that is involved in stress resistance and virulence in Francisella tularensis (19) (Fig. 6A). Another similar operon is associated with aerotolerance and virulence in Bacteroides fragilis (20). Returning to our comparative genomics database, we found that these 6 genes constitute an operon that is broadly conserved in the Pseudomonas clade and is paralogous to the 6-gene operon in the ISS locus (Fig. 6A). This raises the possibility that these six genes within the ISS locus contribute to host-bacterial interactions across diverse bacterial taxa and both plant and animal hosts (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

A conserved subset of genes in the ISS locus contribute to virulence and host association in mammalian pathogens and in Pseudomonas spp. (A) Of the 11 genes in the ISS locus, 6 are contained within a paralogous operon that is present in CH267 and most other Pseudomonas spp. An operon with a similar configuration is also present in mammalian pathogens and has been implicated in virulence. (B) The ISS locus, but not the speE2 gene, promotes rhizosphere colonization. We tested the ΔISSlocus and ΔspeE2 mutant in CH267 and UW4 using a 48-well plate-based rhizosphere colonization assay. Data shown are from 5 days postinoculation. *, P < 0.05 between mutants in a genetic background by ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test; ns, not significant.

To test if the ISS locus is required for Pseudomonas to grow in the Arabidopsis rhizosphere, we tested the UW4 and CH267 ΔISSlocus and ΔspeE2 mutants for rhizosphere growth. We transformed the wild-type and mutant CH267 and UW4 strains with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmid and used a previously described 48-well plate assay to quantify bacterial growth in the rhizosphere (6). Under these conditions, we observed a significant decrease in rhizosphere growth of ΔISSlocus mutants in both the UW4 and CH267 backgrounds (Fig. 6B). We found no decrease in rhizosphere colonization by ΔspeE2 mutants in either the CH267 or UW4 genetic background (Fig. 6B). Together, these data indicate that the ISS locus contributes to growth in the rhizosphere; however, the ΔspeE2 mutant has a loss of ISS while retaining normal rhizosphere growth, indicating a dual role in both rhizosphere colonization and ISS for this genetic locus.

DISCUSSION

Plant root-associated (“rhizosphere”) microbes perform a diversity of functions that benefit their plant hosts, including nutrient uptake and defense. Functional characterization of individual plant-associated bacterial and fungal strains of potential agronomic importance (i.e., growth promoters or nitrogen fixers) is widespread (5). However, closely related strains of bacteria can have very distinct effects on plant growth and defense (13), and these effects can be dependent on environmental context (1). The lack of known correlations between microbial genotype and potential effects on plant hosts presents a challenge when one is attempting to infer the effect that a microbe may have on its plant host from sequence identity alone.

Our use of comparative genomics and isolate phenotyping to identify the genetic basis of a complex microbial-derived trait indicates that this is an effective approach to identifying important microbial traits to improve plant health. For comparative genomics to be effective, traits should be controlled by single or limited genomic loci, and phylogeny should not be predictive of function. In this case, a close relative of ISS strains, Pseudomonas sp. strain Pf0-1 (>99% identical by full-length 16S rRNA to the ISS strains), does not affect systemic defenses (Fig. 1), which allowed us to use comparative genomics to identify the underlying basis. We previously used this approach to find the genomic basis of a pathogenic phenotype within a clade of commensals (14). It has been previously observed that phylogeny is not predictive of function for ISR strains (13), suggesting that comparative genomics may be appropriate to find the basis of additional plant-associated traits.

We found that the ISS locus contains genes involved in both triggering ISS and promoting rhizosphere colonization. Loss of the entire locus results in a loss of ISS and a decrease in growth in the rhizosphere; however, loss of speE2 impairs ISS but not rhizosphere growth, suggesting that there may be multiple plant association functions encoded in this locus. The functions of the speE2 gene and other genes within the ISS locus are not readily apparent from similarity of their products to previously characterized enzymes. As spermidine and other polyamines should directly enhance plant resistance through generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (21), it is possible that the speE2 enzyme converts spermidine or another polyamine to a non-defense-inducing molecule. The highly conserved nature of the portions of speE2-like genes encoding active-site residues suggests a novel function in this enzyme.

While enhancement of systemic susceptibility is not an obviously agronomically useful plant trait, several ISS strains promote growth and enhance resistance to insect pests (6, 7). Using ISS strains might be beneficial for crops where insects are the primary pressure on crop productivity. However, the ubiquity of ISS elicited by plant growth-promoting strains illustrates the complexity of host-microbe interactions and should be considered when the microbiome is being engineered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth conditions.

For all experiments, plants were grown in Jiffy-7 peat pellets (Jiffy Products) under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at 22°C. Seeds were surface sterilized by washing with 70% ethanol for 2 min followed by 5 min in 10% bleach and 3 washes in sterile water. Seeds were stored at 4°C until use. Unless otherwise indicated, seeds were sowed in peat pellets (Jiffy-7) and placed in a growth chamber with 12-h days and 75 μM cool white fluorescent lights at 23°C.

Bacterial growth and 16S rRNA sequencing.

Pseudomonas strains were cultured in LB or King’s B at 28°C. New Pseudomonas strains were isolated from the roots of wild-grown Arabidopsis plants in eastern Massachusetts and British Columbia as previously described (6). New Pseudomonas isolates were preliminary identified based on fluorescence on King’s B and confirmed by 16S rRNA sequencing.

ISS assays.

ISS and ISR assays were performed as described elsewhere (7, 22). Briefly, Pseudomonas rhizosphere isolates were grown at 28°C in LB medium. For inoculation of plant roots for ISR and ISS assays, overnight cultures were pelleted, washed with 10 mM MgSO4 and resuspended to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.02. Jiffy pellets were inoculated 9 days after seed germination with 2 ml of the appropriate bacterial strains at a final OD600 of 0.02 (5 × 105 CFU/g Jiffy pellet). For infections, the leaves of 5-week-old plants were infiltrated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 at an OD600 of 0.0002 (starting inoculum, ∼103 CFU/cm2 leaf tissue). Plants were maintained under low light (<75 μM) and high humidity for 48 h. Leaf punches were harvested, ground, and plated to determine CFU counts.

16S rRNA sequencing, bacterial genome sequencing, assembly, and phylogenomics.

Bacterial DNA preparations were made using Qiagen Purgene kit A. 16S rRNA was amplified using 8F and 1391R and sequenced using 907R. Bacterial genomic library preparation and genome sequencing were performed as previously described (7). Briefly, bacterial DNA was isolated using Qiagen Purgene kit A and sonicated into ∼500-bp fragments. Library construction was performed as previously described (7). Each genomic sample was individually indexed, pooled, and sequenced using MiSeq V3 paired-end 300-bp reads. After barcode splitting, approximately 500,000 to 1 million reads were used for each sample to assemble draft genomes of the Pseudomonas strains CH235, PB100, PB101, PB105, PB106, and PB120 and P. vancouverensis DhA-51. Genome assembly was carried out as previously described (7).

Phylogenomic tree building.

To generate the 29-taxon species tree used in Fig. 2B and Fig. 4E, we made use of an alignment of 122 single-copy genes we previously found to be conserved in all Pseudomonas strains (14). From this amino acid alignment, we extracted 40,000 positions, ignoring sites where >20% of the taxa had gaps. Using RAxMLv8.2.9, we inferred 20 independent trees under the JTT substitution model using empirical amino acid frequencies and selected the one with the highest likelihood. Support values were calculated through 100 independent bootstrap replicates under the same parameters.

To build the 3,886-taxon phylogeny of the Pseudomonas genus in Fig. 5C and Fig. S1, the same 122-gene alignment was used. For computational feasibility, the alignment was randomly subsampled to 10,000 amino acid positions, again ignoring sites that were highly gapped (>20%). FastTree v2.1.9 was used to build the phylogeny using default parameters. The phylogeny was rooted to a clade of Pseudomonas identified as an outgroup to all other Pseudomonas spp. as previously described (14). To more easily visualize this tree, we collapsed monophyletic clades with strong support (as determined by FastTree’s local Shimodaira-Hasegawa test) that correspond with major taxonomic divisions identified by Hesse et al. (15).

To build the tree for the Pseudomonas fluorescens subclade seen in Fig. 5D and Fig. S2, we identified 1,873 orthologs specific to the P. fluorescens clade found in >99% of all strains in the clade and then aligned them all to the hidden Markov models generated by PyParanoid using hmmalign, prior to concatenation. This alignment had 581,023 amino acid positions, which we trimmed to 575,629 positions after masking sites with >10% of taxa with gaps. From this alignment, we randomly subsampled 120,000 sites for our final phylogenomic data set. Using RAxMLv8.2.9, we inferred 20 independent trees in the JTT substitution model using empirical amino acid frequencies and selected the one with the highest likelihood. Support values were calculated through 100 independent bootstrap replicates under the same parameters.

Comparative genomics.

Comparative genomics analyses were performed by using a previously described framework for identifying PyParanoid pipeline and the database we built for over 3,800 genomes of Pseudomonas spp. Briefly, we had previously used PyParanoid to identify 24,066 discrete groups of homologous proteins which covered >94% of the genes in the original database. Using these homolog groups, we annotated each protein-coding sequence in the newly sequenced genomes and merged the resulting data with the existing database, generating presence-absence data for each of the 24,066 groups for 3,886 total Pseudomonas genomes.

To identify the groups associated with induction of systemic susceptibility, we compared the presence-absence data for 4 strains with ISS activity (Pseudomonas strains CH229, CH235, CH267, and UW-4) and 1 strain with no activity (Pseudomonas strain Pf0-1). We initially suspected that ISS activity was due to the presence of a gene or pathway (i.e., not the absence of a gene) and thus initially focused on genes present only in Pf0-1. We identified 29 groups that were present in the 4 ISS strains but not in Pf0-1.

To obtain the correlation coefficients in Fig. 4D and Fig. 5A, we coded group presence or absence as a binary variable and calculated Pearson coefficients across all 3,886 genomes. To calculate the correlation coefficients in Fig. 5B, we split the genomic database into 50-kb contiguous regions and assessed group presence or absence within each region. Because this data set is heavily zero inflated, we ignored regions that had none of the 11 groups, taking the Pearson coefficient of the 11 genes over the remaining regions.

Initial annotation of the ISS groups was based on generic annotations from GenBank. Further annotation of the 11 groups specific to the ISS locus was carried out using the TMHMM v2.0 server, the SignalP 4.1 server, and a local Pfam search using the Pfam-A database from Pfam v31.0. To identify homologous genes in the genomes of Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica and Bacteroides fragilis YCH46, we relied on locus tags reported in the literature, which we confirmed using annotation based on another Pfam-A domain search.

Deletion of the speE2 gene and 11-gene ISS locus.

Deletions in strains CH267 and UW4 were constructed by a two-step allelic exchange as described elsewhere (23). The flanking regions directly upstream and downstream of the 11-gene ISS locus or the speE2 gene were amplified and joined by overlapping PCR using genomic DNA as the template and primers listed in Table 2. Following digestion, the product was ligated into the pEXG2 suicide vector that contains the sacB gene for counterselection on sucrose (24). The recombinant plasmid was then transformed into calcium-competent Escherichia coli DH5α by heat shock. After confirmation of correct insertion by PCR and sequencing, the plasmid was transformed into WM3064 (25). Conjugation of the plasmid into CH267 and UW4 from WM3064 was performed by biparental mating on King’s B medium supplemented with diaminopimelic acid, and transconjugants were selected using 10 μg/ml gentamicin and 15 μg/ml nalidixic acid. The second recombination, leading to plasmid and target DNA excision, was selected for by using sucrose counterselection. Gene deletions in CH267 and UW4 were confirmed by PCR amplification of the flanking regions with primers listed in Table 2, agarose gel electrophoresis, and Sanger sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to generate the mutant Pseudomonas strains analyzed in this study

| Strain | Primer type | Primer name | Restriction site | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH267 ΔISSlocus | Upstream forward | CH409 | HindIII | AAAAAGCTTAGTCGCAACCTCGCCTCGACTGAC |

| Upstream reverse | CH410 | AAACGGGCGGGAGCAGCACTTGG | ||

| Downstream forward | CH411 | CACTGACTCCGCTTATTGTTTTGTGTC | ||

| Downstream reverse | CH412 | EcoRI | AAAGAATTCTTCACGCCGCCGCAGGATGTC | |

| Upstream confirmation | PB401 | CGCTATGACCTGGGCCGCAACGAA | ||

| Downstream confirmation | PB402 | CCGACGCCGACCATGAGCGAAA | ||

| CH267 ΔspeE | Upstream forward | CH413a | HindIII | AAAAAGCTTGCTCCAGCAAAACCGTCGCTCCA |

| Upstream reverse | CH414a | CTCTCGTCATCCGATCATTCCCACGCGG | ||

| Downstream forward | CH415 | GAATGATTGTTCCCATGCATAGCGTGG | ||

| Downstream reverse | CH416a | EcoRI | AAAGAATTCCCGGGCTCGACTGGTTCCCGA | |

| Upstream confirmation | PB403 | CTACAGCCAACTCAAGGAGGCCAA | ||

| Downstream confirmation | PB404 | CGGGTGAGGTCTCGAACGAGATGT | ||

| UW4 ΔISSlocus | Upstream forward | CH401 | HindIII | AAAAAGCTTACGCCTCGGCCATCGGTGTACC |

| Upstream reverse | CH402 | GAAAGGCTCCTGCAGAAGATCGAAC | ||

| Downstream forward | CH403 | GTAACACCTCCAAACGTTCCGGGAT | ||

| Downstream reverse | CH404 | EcoRI | AAAGAATTCAACGCACCTGCACATCGGCTGCG | |

| Upstream confirmation | PB405 | GGGTCATGTCCCTGACCAGCA | ||

| Downstream confirmation | PB406 | GGGTCGAATTCCGTGTCGCCAA | ||

| UW4 ΔspeE | Upstream forward | CH405 | HindIII | AAAAAGCTTGAGCCGATTGAGCTGGATGCGG |

| Upstream reverse | CH406 | TACGACTTCCATGGTCCAGGTGCG | ||

| Downstream forward | CH407 | TCGGGGGGCTGGCTCAAAGG | ||

| Downstream reverse | CH408 | EcoRI | AAAGAATTCACGAGTCGGCGCTCAAACGCG | |

| Upstream confirmation | PB407 | CGCGAACCTGTGGACCAGCGAGTT | ||

| Downstream confirmation | PB408 | CGCGAACCGCGCTGCAAGAA | ||

| plac-speE2 | Upstream forward | speE_up2 | HindIII | AAAAAGCTTCCACGCTATGCATGGGAACAA |

| Downstream reverse | speE_down1 | BamHI | AAAGGATCCGGATGACGAGAGTCACTGC | |

| Confirmation primer 1 | PB409 | GGGCGTGTCGAATACCGGCGA | ||

| Confirmation primer 2 | PB410 | GCGCGGCTCGCCGTT | ||

| Confirmation primer 3 | PB411 | CGCCGCCGGCGATGGA |

Complementation of the speE2 gene.

The speE2 gene was amplified by PCR using CH267 genomic DNA as the template, as well as the primers listed in Table 2. Following restriction digestion, the ∼2.6-kb insert was ligated into the pBBR1MCS-2 vector at the multiple-cloning site located downstream of a lac promoter. Ligation mixture was then introduced into E. coli DH5α by heat shock, and transformants were selected using LB medium supplemented with 25 to 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The presence of the correct insert was confirmed by PCR, restriction digestion, and Sanger sequencing. pBBR1-MCS2::placZ-speE2CDS plasmids were maintained in E. coli DH5α λpir with 25 μg/ml of kanamycin. To construct a conjugating strain, calcium-competent E. coli WM3064 was first transformed with pBBR1-MCS2::placZ-speE2CDS or pBBR1-MCS2 by heat shock. To conjugate Pseudomonas sp. strain CH267, 1 ml of overnight cultures of Pseudomonas sp. strain CH267 and E. coli WM3064 carrying the appropriate plasmids were washed twice and resuspended with 0.5 ml of 100 mM MgCl2. The resuspended Pseudomonas sp. strain CH267 was mixed with E. coli WM3064 strains at a 1:2 ratio. Six 25-μl mating spots were placed on LB plates supplemented with 0.3 mM diaminopimelic acid (DAP). The mating spots were allowed to dry before incubation at 28°C for 4 h. The mating spots were then scraped off and resuspended in 1 ml of 100 mM MgCl2. A 100-μl portion of the suspension was plated on LB-kanamycin. Colonies were restreaked to confirm antibiotic resistance.

Multiple-sequence alignment and SSN generation.

Multiple-sequence alignment was performed with Clustal Omega (26). The sequence similarity network (SSN) was created using the enzyme function initiative (EFI-EST) web tool (27) by inputting the SpeE2 amino acid sequence with the amino acid sequences from the spermidine synthase tetramerization domain with the code PF17284 using UniRef90 seed sequences instead of the whole family. Sequences with fewer than 100 amino acids were also excluded, resulting in a total of 6,523 sequences. An alignment score threshold or E value cutoff of 10−100 was used to generate the SSN, which was visualized using Cytoscape (28).

Rhizosphere colonization assay.

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown in 48-well plates and rhizosphere growth of bacteria was quantified as previously described (6). Briefly, Arabidopsis seeds were placed individually in 48-well clear-bottom plates with the roots submerged in hydroponic medium (300 μl 0.5× MS [Murashige and Skoog] medium plus 2% sucrose). The medium was replaced with 270 μl 0.5× MS medium with no sucrose on day 10, and plants were inoculated with 30 μl bacteria at an OD600 of 0.0002 (final OD600, 0.00002; ∼1,000 cells per well) on day 12. Plants were inoculated with wild-type Pseudomonas CH267 or UW4 containing plasmid pSMC21 (pTac-GFP) (29). Fluorescence was measured with a SpectraMax i3x fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices) (481 nm/515 nm, excitation/emission) 5 days postinoculation. A standard curve relating fluorescence to OD was generated to estimate the number of CFU per well (OD600 = 1 = 5 × 108 CFU/ml).

Data availability.

Data for the Whole Genome Shotgun project have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession numbers RRZJ00000000 (CH235), RRZK00000000 (DhA-51), RWIM00000000 (PB106), RWIN00000000 (PB120), RWIO00000000 (PB105), RWIQ00000000 (PB100), and RWIR00000000 (PB101). The versions described in this paper are versions RRZJ01000000 (CH235), RRZK01000000 (DhA-51), RWIM01000000 (PB106), RWIN01000000 (PB120), RWIO01000000 (PB105), RWIQ01000000 (PB100), and RWIR01000000 (PB101).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant (NSERC-RGPIN-2016-04121) and a Seeding Food Innovation grant from George Weston Ltd. awarded to C.H.H. Additional support came from a Life Sciences Research Foundation Fellowship from the Simons Foundation awarded to R.A.M., a fellowship from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation awarded to Y.S., a Chinese Graduate Scholarship Council award to Y.L., and an NSERC CGS-M award to Z.L.

C.H.H., R.A.M., and P.B. designed experiments. P.B., Y.S., Y.L., and C.H.H. performed experiments. C.H.H., R.A.M., and Z.L. analyzed data, and R.A.M. performed genome assembly, annotation, phylogenetic analysis, and comparative genomics. M.A.H. and K.S.R. performed bioinformatic analyses of speE2 function. C.H.H., P.B., and R.A.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all the other authors.

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Citation Beskrovnaya P, Melnyk RA, Liu Z, Liu Y, Higgins MA, Song Y, Ryan KS, Haney CH. 2020. Comparative genomics identified a genetic locus in plant-associated Pseudomonas spp. that is necessary for induced systemic susceptibility. mBio 11:e00575-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00575-20.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Bouffaud M-L, Touraine B, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Muller D, Legendre L, Wisniewski-Dyé F, Prigent-Combaret C. 2013. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front Plant Sci 4:356. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaepen S, Vanderleyden J, Remans R. 2007. Indole-3-acetic acid in microbial and microorganism-plant signaling. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31:425–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glick BR. 2005. Modulation of plant ethylene levels by the bacterial enzyme ACC deaminase. FEMS Microbiol Lett 251:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangera MG, Thomashow LS. 1999. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster for synthesis of the polyketide antibiotic 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2-87. J Bacteriol 181:3155–3163. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.10.3155-3163.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieterse CMJ, de Jonge R, Berendsen RL. 2016. The soil-borne supremacy. Trends Plant Sci 21:171–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haney CH, Samuel BS, Bush J, Ausubel FM. 2015. Associations with rhizosphere bacteria can confer an adaptive advantage to plants. Nat Plants 1:15051. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haney CH, Wiesmann CL, Shapiro LR, Melnyk RA, O'Sullivan LR, Khorasani S, Xiao L, Han J, Bush J, Carrillo J, Pierce NE, Ausubel FM. 2018. Rhizosphere-associated Pseudomonas induce systemic resistance to herbivores at the cost of susceptibility to bacterial pathogens. Mol Ecol 27:1833–1847. doi: 10.1111/mec.14400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huot B, Yao J, Montgomery BL, He SY. 2014. Growth-defense tradeoffs in plants: a balancing act to optimize fitness. Mol Plant 7:1267–1287. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Wees SCM, Pieterse CMJ, Trijssenaar A, Van 't Westende YAM, Hartog F, Van Loon LC. 1997. Differential induction of systemic resistance in Arabidopsis by biocontrol bacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 10:716–724. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah S, Li J, Moffatt BA, Glick BR. 1998. Isolation and characterization of ACC deaminase genes from two different plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Can J Microbiol 44:833–843. doi: 10.1139/w98-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compeau G, Al-Achi BJ, Platsouka E, Levy SB. 1988. Survival of rifampin-resistant mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida in soil systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:2432–2438. doi: 10.1128/AEM.54.10.2432-2438.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohn WW, Wilson AE, Bicho P, Moore E. 1999. Physiological and phylogenetic diversity of bacteria growing on resin acids. Syst Appl Microbiol 22:68–78. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berendsen RL, van Verk MC, Stringlis IA, Zamioudis C, Tommassen J, Pieterse CMJ, Bakker P. 2015. Unearthing the genomes of plant-beneficial Pseudomonas model strains WCS358, WCS374 and WCS417. BMC Genomics 16:539. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1632-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melnyk RA, Hossain SS, Haney CH. 2019. Convergent gain and loss of genomic islands drive lifestyle changes in plant-associated Pseudomonas. ISME J 13:1575–1588. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesse C, Schulz F, Bull CT, Shaffer BT, Yan Q, Shapiro N, Hassan KA, Varghese N, Elbourne LDH, Paulsen IT, Kyrpides N, Woyke T, Loper JE. 2018. Genome-based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environ Microbiol 20:2142–2159. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu C-D, Itoh Y, Nakada Y, Jiang Y. 2002. Functional analysis and regulation of the divergent spuABCDEFGH-spuI operons for polyamine uptake and utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 184:3765–3773. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.14.3765-3773.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H, Min J, Zeng H, McCloskey DE, Ikeguchi Y, Loppnau P, Michael AJ, Pegg AE, Plotnikov AN. 2008. Crystal structure of human spermine synthase: implications of substrate binding and catalytic mechanism. J Biol Chem 283:16135–16146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710323200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu H, Min J, Ikeguchi Y, Zeng H, Dong A, Loppnau P, Pegg AE, Plotnikov AN. 2007. Structure and mechanism of spermidine synthases. Biochemistry 46:8331–8339. doi: 10.1021/bi602498k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieppedale J, Sobral D, Dupuis M, Dubail I, Klimentova J, Stulik J, Postic G, Frapy E, Meibom KL, Barel M, Charbit A. 2011. Identification of a putative chaperone involved in stress resistance and virulence in Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun 79:1428–1439. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01012-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang YP, Dallas MM, Malamy MH. 1999. Characterization of the BatI (Bacteroides aerotolerance) operon in Bacteroides fragilis: isolation of a B. fragilis mutant with reduced aerotolerance and impaired growth in in vivo model systems. Mol Microbiol 32:139–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neill EM, Mucyn TS, Patteson JB, Finkel OM, Chung E-H, Baccile JA, Massolo E, Schroeder FC, Dangl JL, Li B. 2018. Phevamine A, a small molecule that suppresses plant immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E9514–E9522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803779115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cecchini N, Song Y, Roychoudhry S, Greenberg J, Haney C. 2019. An improved bioassay to study Arabidopsis induced systemic resistance (ISR) against bacterial pathogens and insect pests. Bio Protoc 9:e3236. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Beskrovnaya P, Melnyk RA, Hossain SS, Khorasani S, O’Sullivan LR, Wiesmann CL, Bush J, Richard JD, Haney CH. 2018. A genome-wide screen identifies genes in rhizosphere-associated Pseudomonas required to evade plant defenses. mBio 9:e00433-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00433-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rietsch A, Vallet-Gely I, Dove SL, Mekalanos JJ. 2005. ExsE, a secreted regulator of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:8006–8011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503005102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madeira F, Park YM, Lee J, Buso N, Gur T, Madhusoodanan N, Basutkar P, Tivey ARN, Potter SC, Finn RD, Lopez R. 2019. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47:W636–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, Imker HJ, Sadkhin B, Slater DR, Whalen KL. 2015. Enzyme function initiative-enzyme similarity tool (EFI-EST): a web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim Biophys Acta 1854:1019–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. 2003. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloemberg GV, O'Toole GA, Lugtenberg BJJ, Kolter R. 1997. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for Pseudomonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:4543–4551. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.11.4543-4551.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamers JG, Schippers B, Geels FP. 1988. Soil-borne diseases of wheat in the Netherlands and results of seed bacterization with pseudomonads against Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, associated with disease resistance, p 134–139. In Jorna ML, Slootmaker LAJ (ed), Cereal breeding related to integrated cereal production. Proceedings of the conference of the Cereal Section of EUCARPIA. Pudoc, Wageningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geels FP, Schippers B. 1983. Selection of antagonistic fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. and their root colonization and persistence following treatment of seed potatoes. J Phytopathol 108:193–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1983.tb00579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell CR, Stipanovic RD. 1979. Control of Rhizoctonia solani on cotton seedlings with Pseudomonas fluorescens and with an antibiotic produced by the bacterium. Phytopathology 69:480–482. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price MN, Wetmore KM, Waters RJ, Callaghan M, Ray J, Liu H, Kuehl JV, Melnyk RA, Lamson JS, Suh Y, Carlson HK, Esquivel Z, Sadeeshkumar H, Chakraborty R, Zane GM, Rubin BE, Wall JD, Visel A, Bristow J, Blow MJ, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer AM. 2018. Mutant phenotypes for thousands of bacterial genes of unknown function. Nature 557:503–509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation matrix of 16S rRNA similarity of new Pseudomonas isolates from the Arabidopsis rhizosphere. Isolates were selected based on similarity (>97% identical by partial 16S rRNA) to CH267 (CH235, PB101, and PB106) or distance (<97% identity by partial 16S rRNA) to CH267 (PB120, PB100, PB105). Isolates from the rhizosphere of Arabidopsis plants growing in Massachusetts, USA (*), or British Columbia, Canada (#). Download FIG S1, EPS file, 2.1 MB (2.2MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unique loci identified in comparative genomics. The genome content of 4 ISS strains (CH267, CH235, UW4, and CH229) was compared with that of the closely related non-ISS strain Pf0-1. Seventeen predicted protein-coding genes were identified. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (11.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Distribution of loci identified by comparative genomics ISS loci across Pseudomonas strains. Comparative genomics between ISS strains UW4, CH229, CH235, and CH267 (black arrows) and non-ISS strain Pf0-1 (red arrow) identified 17 predicted protein-coding genes of >100 aa that were absent in Pf0-1 and present in strains that induce ISS. Eleven of these genes were found in a single genomic locus (box) and were absent in the non-ISS strain WCS365. Download FIG S2, EPS file, 1.7 MB (1.7MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The ISS locus is highly variable between closely related strains. The 11 genes in the ISS locus are present in the ISS strains Pf0-1, CH235, CH267, and CH299 but absent in Pf0-1. Genes in the ISS locus are colored as in the key at the bottom of the figure and in Fig. 2. Conserved genes not unique to the ISS strains are colored similarly among strains; genes in gray are not conserved between strains at this locus. In CH229, Pf0-1, and CH267 the genes flanking the ISS locus are conserved in the same orientation, suggesting a recent insertion or deletion event. Download FIG S3, EPS file, 1.2 MB (1.3MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2020 Beskrovnaya et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Data Availability Statement

Data for the Whole Genome Shotgun project have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession numbers RRZJ00000000 (CH235), RRZK00000000 (DhA-51), RWIM00000000 (PB106), RWIN00000000 (PB120), RWIO00000000 (PB105), RWIQ00000000 (PB100), and RWIR00000000 (PB101). The versions described in this paper are versions RRZJ01000000 (CH235), RRZK01000000 (DhA-51), RWIM01000000 (PB106), RWIN01000000 (PB120), RWIO01000000 (PB105), RWIQ01000000 (PB100), and RWIR01000000 (PB101).