Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is a reminder that insufficient income security in periods of ill health leads to economic hardship for individuals and hampers disease control efforts as people struggle to stay home when sick or advised to observe quarantine. Evidence on income security during periods of ill health is growing but has not previously been reviewed as a full body of work concerning low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). We performed a scoping review to map the range, features, coverage, protective effects and equity of policies that aim to provide income security for adults whose ill health prevents them from participating in gainful work. A total of 134 studies were included, providing data from 95% of LMICs. However, data across the majority of these countries were severely limited. Collectively the included studies demonstrate that coverage of contributory income-security schemes is low, especially for informal and low-income workers. Meanwhile, non-contributory schemes targeting low-income groups are often not explicitly designed to provide income support in periods of ill health, they can be difficult to access and rarely provide sufficient income support to cover the needs of eligible recipients. While identifying an urgent need for more research on illness-related income security in LMICs, this review concludes that scaling up and diversifying the range of income security interventions is crucial for improving coverage and equity. To achieve these outcomes, illness-related income protection must receive greater recognition in health policy and health financing circles, expanding our understanding of financial hardship beyond direct medical costs.

Keywords: health policy, public health

Key questions.

What is already known?

Financial protection through reduction of out-of-pocket medical expenditures is already a prominent element of universal health coverage (UHC) within Sustainable Development Goal 3. However, UHC does not include mechanisms to compensate for income loss due to ill health.

Income security during periods of ill health is severely under-researched, especially in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

What are the new findings?

This scoping review demonstrates that while most LMICs have policies in place for income security during periods of ill health, effective coverage is very low and existing schemes often exclude those who have the greatest need.

There are several prominent access barriers, particularly for those with short-term to medium-term illnesses who are not in the formal workforce. However, firm conclusions about coverage, equity and effects cannot be drawn due to the dearth of published studies on the topic.

What do the new findings imply?

Income security during periods of ill health needs to become a more prominent part of global health research and action.

With income security contributing to better health outcomes, illness-related social protection needs to be integrated into health policies beyond UHC, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of indirect medical costs.

Introduction

The advent of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has placed holistic, multisectoral development strategies in mainstream policy-making spaces.1 Correspondingly, this shift has breathed fresh life into the field of public health by emphasising the range of social, economic, environmental and cultural determinants of health.2 Of these, poverty is both a determinant and consequence of ill health.3 As such, SDG 3 ‘Good Health and Well-being’ aims to reduce a range of adverse health outcomes and the associated financial burden of them, primarily through the realisation of Universal Health Coverage (UHC).1 4 5 However, while UHC has the potential to minimise impoverishment due to high out-of-pocket healthcare costs, it does not inherently protect against income loss for individuals who cannot participate in gainful work due to ill health.6–9 This relationship has become apparent in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen a staggering number of illness-related unpaid leaves of absence.10 Of the population who are affected, many do not have access to social safety nets, leaving them vulnerable to poor health and poverty.10

Indeed, a cursory exploration of the SDGs and broader policies from WHO demonstrates a lack of analysis on income loss due to short-term and long-term illness.6 9 11 Further, despite WHO’s leading role in The Coalition of the Social Protection Floor Initiative,11 a decade has passed since their last publication on income security and health.12 As such, this study aims to refocus the attention on this topic, by consolidating the range of existing policies and practices which protect income during periods of ill health, specifically in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Defining income security

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) guidelines, income security denotes ‘adequate income, either earned or in the form of social security and other benefits (which also) encompasses the level of income (absolute and relative to needs), assurance of receipt, and expectation of current and future income, both during working life and in old age or disability retirement’.13 Expanding on this definition, the ILO highlights that income security requires a ‘replacement of income which has been lost temporarily as a result of injury, disability or sickness’, among other reasons.14

Defining ill health

While seemingly straightforward, the language surrounding income-reducing health conditions is vague and inconsistent.15 Indeed, the above definition of income security references ‘injury, disability or sickness’, all of which can be non-discrete and, by definition, overlap.12 15 The term ‘ill health’ is used in this study as an umbrella descriptor for these terms and is defined as: ‘a condition of inferior health in which some disease or impairment of function is present’.16

Further, periods of ill health can lead to income loss when impaired function reduces ability to participate in gainful work, or when opportunity to work is lost for other health-related reasons, such as limitations caused by infectious disease legislation6 or when work time is lost due to healthcare utilisation. Therefore, within the context of this study, the term ‘ill health’ specifically refers to any condition, short or long term, which reduces a person’s ability to participate in gainful work. This definition is constructed on principles of the of the 2001 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model, which accounts for medical, social, environmental and individual perspectives on health.17–19

The health benefits of income security during periods of ill health

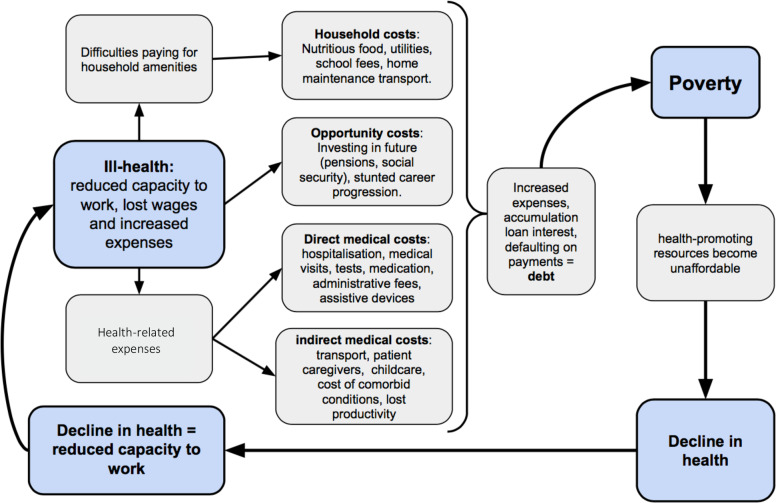

Income loss during periods of ill health can greatly reduce an individual’s resilience to health shocks. First, income loss can reduce access to healthcare by diminishing financial capacity to cover health-related expenses.20–22 Second, income loss can increase future health vulnerability for the individual and the household by hindering a nutritionally balanced diet,23 maintaining healthy living conditions12 and sustaining adequate resources for household dependents (figure 1) 21 24. While UHC can reduce these costs, it does not eliminate insecurity.8–10 Income security has the potential to complement UHC in improving the efficacy of healthcare interventions by helping people pay for costs associated with repeat health visits, prescriptions and assistive devices. This ensures that their condition can be treated effectively and may prevent a more severe illness from developing.25 26 It can also reduce the need to return to work when sick (presenteeism), promoting recovery, while also reducing the risk of transmitting infectious diseases.6 25 Moreover, a stable income allows the maintenance of healthy living conditions, helping to maintain the social, mental and physical health of the household.27 28

Figure 1.

Diagram to show the direct and indirect costs of ill health which facilitate a spiral of decline in health and income. Adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead.3

Delivering income security

Formal income security schemes range in design and vary within different economic, social and political contexts. Broadly, these interventions can be divided into two categories; contributory and non-contributory.

Contributory schemes

Contributory schemes require payment as a prerequisite to receiving support, either in the form of labour hours or monetary contributions.29 Schemes may be provided through private insurance companies, or by employers who may be legally obligated.25 29 30 Further, many income security schemes exist in collaboration with the individual, the employer and the government. These quasi-public schemes, referred to as ‘social insurance’, require contributions from the worker's payroll, the employer and the state, to create a fund which can be accessed if an individual cannot participate in gainful employment.29 31 32 Employers’ liability to continue to pay salary during sick leave ("sick-pay") can be an alternative or complement. Lastly, microfinance can serve as a form of contributory scheme, but are rarely designed specifically for the purpose of income security in periods of ill health.

Non-contributory schemes

Non-contributory schemes do not require formal contributions towards an insurance fund and are typically financed by governments or non-governmental organisations.29 These schemes can be means tested or non-means tested. In means-tested schemes, only recipients with a certain income are eligible. Non-means tested schemes, on the other hand, can be accessed by anyone, regardless of income (universal schemes), and instead depend on a predetermined category, such as disability (categorical schemes).29 These are most commonly delivered as conditional cash transfers (CCTs) or unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) schemes.29

The difference between CCTs and UCTs refers to the responsibility placed on the recipient.33 CCTs offer cash payments to households with the expectation that they comply with certain requirements, such as school enrolment or health check-ups.32–34 UCTs, however, do not require anything in return.35 Several studies have reported that the conditions associated with CCTs were impractical for people who are experiencing ill health, resulting in considerably lower enrolment rates for people with disabilities.36 37 As a result of these findings, CCTs were not included in this study.

Study purpose

This study aimed to map the range, features, coverage, protective effects and equity of formal policies in LMICs, which provide income security for adults whose ill health prevents them from participating in gainful work. Accordingly, the following specific research questions were addressed:

What are the key features of income protection schemes for individuals experiencing ill health in LMICs?

How effective are income protection schemes in LMICs in guarding against financial insecurity during periods of ill health?

How equitable are income protection schemes in LMICs, in terms of the level of coverage in different populations?

Methods

A scoping review was conducted, which included all relevant literature on social protection and income security in LMICs. This method was chosen owing to the exploratory, broad and heterogeneous nature of the topic at hand.38 The final scoping protocol was informed by The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual.39 The final design was cross referenced with the more concise Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist to ensure that all reporting requirements have been met.40

Search strategy

Searches were conducted of PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL, Global Health, ProQuest and EconBiz. The search included all full-text sources that discussed sickness and disability-specific income security, with the exception of CCTs. Further, the eligibility criteria specifically included articles published in English between 2009 and 2019, including grey literature. Relevant words related to ‘income security’, ‘ill health’ and ‘LMICs’ were grouped by theme, using the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’, to build the final search strategy (online supplementary box 1).

bmjgh-2020-002425supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Selection of search results

Owing to the lack of consensus surrounding the terminology for income security during periods of ill health, and the heterogeneity of the policies that exist across geographical locations, the search strategy deliberately allowed for a wide range of search results. The selection process began by scanning through the titles and abstracts of the results to determine if they met the eligibility criteria. All results meeting the eligibility criteria were entered into Mendeley. Finally, the full text of each record was appraised, and ineligible records were excluded.

Data extraction and charting of results

Data from the included papers were charted into a table where the specific characteristics of each study were recorded. These characteristics included: authorship, year of publication, study design, study location, study objectives, study population, type of intervention, name of intervention and major findings. On completion of this step, the reference lists of all eligible articles were checked to determine if any relevant papers were missed. After a review of the titles, abstracts and then full-text review, papers that met the eligibility criteria were included.

Critical appraisal

This study did not employ a systematic critical appraisal of each study. Instead, unqualified remarks were noted during the charting process. Identifying unqualified and misreported information is integral in mapping the extent of literature in this field and understanding if and how certain discourses surrounding social protection are (re)produced in academia.41–43

Synthesis of results

Following the charting process, the data were synthesised using an inductive content analysis approach. This involved an appraisal of each study’s main findings to then stratify into a series of themes and subthemes (see online supplementary table 1). This process also allowed for the identification of overlapping connections between themes. The volume of quantitative data was too small to analyse using statistical methods, but a discussion of descriptive quantitative results was included in the final analysis.

bmjgh-2020-002425supp002.pdf (130.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Involvement of patients and public was not relevant in this research since it was a literature review.

Results

Study inclusion and characteristics

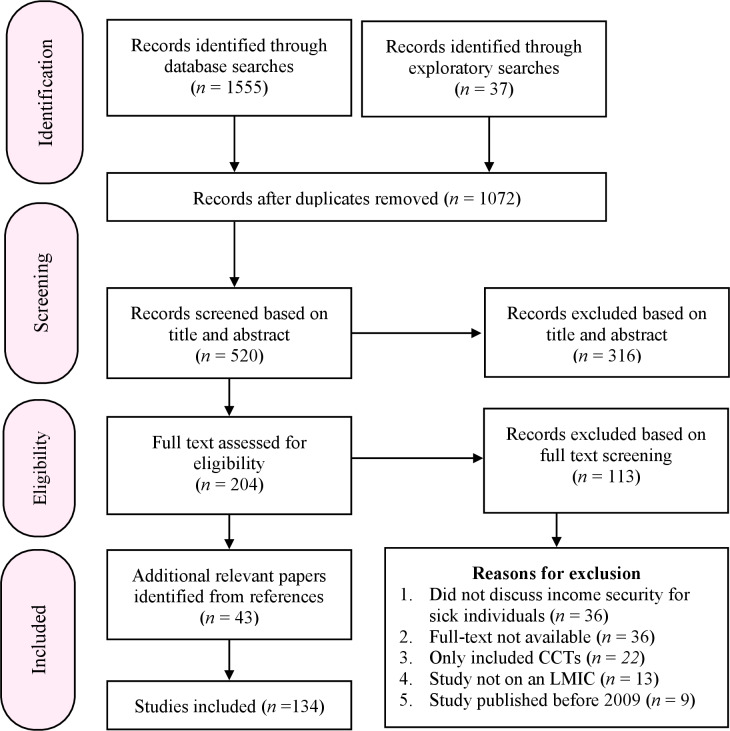

Of the 1592 records identified in the searches, 91 studies were deemed relevant for the purpose of this study. A further 43 records were identified from the references. Together, a total of 134 studies were included in this review (figure 2). Included studies are summarised in online supplementary table 1. Studies are enumerated by study types, location, target populations and type of schemes in online supplementary table 2. The 134 studies contained data on 131 countries, out of a total 138 LMIC countries (95%). However, data for 62 of these countries were provided from one single source, the ILO World Social Protection Report (2017). Only 76 countries were represented in the remaining studies. Overall, upper-middle-income countries gained the most extensive coverage, followed by lower-middle-income countries and low-income countries (online supplementary table 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram to show each stage of the scoping search process, adapted from the PRISMA statement by Liberati et al.44 CCT, conditional cash transfer; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; LMIC, low-income and middle-income countries

Conceptualising ill health

The included studies demonstrate a lack of practical consensus on what constitutes ‘too ill to work’,45 particularly when considering short-term illnesses. While 11 studies loosely described policies for short-term illnesses, none described what specifically constituted a short-term illness. Three studies addressed the length of time that an individual could receive payments,25 46 47 yet failed to elaborate on what happens if their illness exceeds the timeframe. Long-term illnesses were more clearly defined, with studies collectively demonstrating a general shift towards using the ICF model when determining the eligibility of applicants.48–50 However, 27 studies showed that degrees of incapacity remain challenging to categorise objectively, stating that criteria were often inconsistent and unclear.22 51

Legal protections against illness-induced poverty

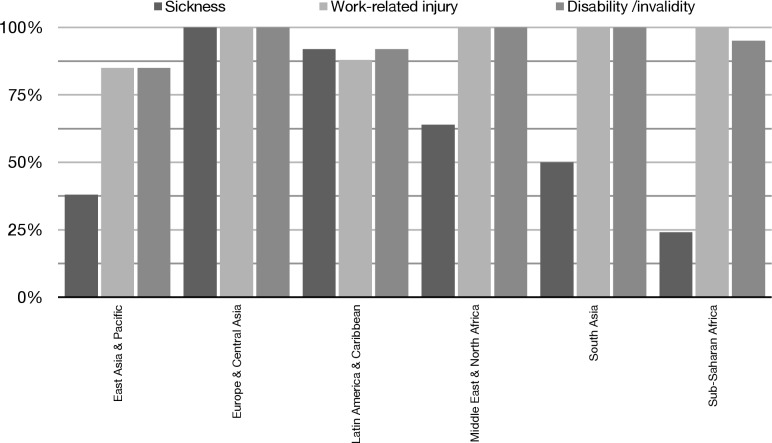

The majority of LMICs have policies stipulating varying levels of illness-related income protection for sickness, work-related injury or disability.14 However, comprehensive legal protection, which encompasses all three of these protections, is only available in 47% of LMICs.14 In addition, the regional distribution of legal protections varies significantly (figure 3). While all forms of protection are legally mandated in all European and Central Asian countries, only 17% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa offer the same scope of legal coverage.14 Legal coverage is consistently low across most of Asia, the Pacific and Africa,14 and does not reflect actual coverage. For instance, population coverage of injury compensation and ‘severe’ disability benefits range between 4.8%–100% and 0.1%–100%, respectively.14 Insufficient financing, ineffective legal enforcement, inadequate health assessments, social inequalities, exclusion of informal workers, a lack of political will and ineffective monitoring or measurement tools were reported as contributing factors towards gaps in coverage.14 52–58

Figure 3.

Percentage of countries offering legally mandated sickness, injury and disability payments (stratified by region). Source: ILO14. ILO, International Labour Organization.

Contributory schemes: social insurance

Features of social insurance

The delivery of legally mandated income protection is most commonly delivered through compulsory social insurance.14 29 However, the level of protection varies significantly across LMICs, both in terms of the benefits offered and the scope of legal coverage.14 For instance, 30% of countries do not offer injury compensation through social insurance. Further, there are discrepancies in coverage even in countries where injury compensation is grounded in national legislation.14 Enforcement of social insurance regulations is inadequate in many LMICs and rarely extend to protect those working in small companies or in the informal economy (table 1).59–6

Table 1.

Factors which facilitate exclusion in social insurance

| Requirements | Implications | Country |

| A legally binding, long-term employment contract | Informal workers are more likely to have a short-term contract or no contract at all. | China,62 Vietnam63 64; Sao Tome and Principe,65 South Africa27; Thailand66 |

| Contributions towards social insurance must be made consistently, over a minimum time period (eg, 3+months) | Informal labour involves short term and sporadic work which generates an inconsistent level of income. | Bosnia and Herzegovina67; Thailand,66 Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Morocco25; |

| Legally binding obligations only required from (or monitored in) formal sector industries. | Informal workers are not offered a chance to participate in social insurance by their employers if there is no legal incentive to do so. | India,68 Vietnam,63 China,62 Thailand,66 Colombia69 |

The protective capacity of social insurance

Little data has been identified on the amount paid to people who are sick, injured or have a disability, or if these benefits meet basic needs. Six studies discussed the level of pay, stating that replacement rates vary between ‘lump sums’ and 100% of wages.25 46 47 54 70 Four studies highlighted issues of non-compliance, demonstrating that legal provision does not necessarily reflect real benefits.59–61 71 Lastly, no data were provided on whether social insurance payments met basic needs.

A second factor influencing the protective capacity of social insurance pertains to the length of time that benefits are available for. Only two studies report this feature, explaining that payments can span anywhere from a maximum of 7 days to 2 years.14 25 Additional sources are less clear in defining a time frame, using vague descriptions such as ‘until working capacity is covered'.46 Following this, however, there is no information on the support given to those whose illness persists after their insurance entitlements expire.

The degree of equity in social insurance schemes

Results highlight large disparities in the populations that are adequately covered by social insurance. For instance, Dias et al52 assert that low-income claimants in Brazil face greater difficulties in obtaining the support that they are entitled to.52 Injury insurance claimants in Colombia were reported to have claims rejected if the aetiology of their injury was not correctly identified.69 Additionally, Thailand’s system offers greater financial support to those who are able to contribute more towards their insurance, while those who contribute less are only entitled to a small lump sum payment, in place of a sustained income.53 Further, four studies report that employees must have contributed a certain number of work hours, within a specific timeframe, in order to meet the qualifying conditions.

While there are differences in entitlements for those who do have legal access to social insurance, there are even greater disparities between those who are, and are not, included in social insurance schemes. More specifically, those who are employed informally often face structural barriers which inhibit access to social insurance. Further, migrant workers and people with disabilities are more likely to engage in informal work and thus face higher levels of exclusion from social insurance.14 27 72–74

Finally, five studies discuss the availability of voluntary insurance schemes for informal workers.14 62 66 75 76 However, uptake of these schemes remains low among those in informal employment.76 This is largely attributed to a lack of awareness of these schemes and the difficulties in raising a surplus income to pay for insurance.53 66 77

Contributory schemes: microfinance

The features of microfinance

Nine studies discussed microfinance schemes which specifically include people who are sick or have a disability in their targeting criteria.45 75 78–84 The aim of these schemes is to provide low-interest loans to promote income generating activities for those who cannot participate in full-time employment but still have the capacity to generate an income.84 Recipients can choose how their loan is spent, empowering people to start their own business and produce a sustainable income.

The protective capacity of microfinance

All included studies viewed microfinance favourably, identifying it as an effective tool in protecting income during periods of ill health. Three studies reported that access to credit through microfinance schemes was able to smooth consumption in labour-contained households that experienced health shocks.45 75 83 Further, microfinance was shown to empower people with disabilities, both economically and socially.79–81 These populations were provided with greater levels of financial autonomy and reported greater levels of self-worth.79

The degree of equity of microfinance

From a policy perspective, the design of microfinance schemes aims to expand financial protection to under-represented groups, particularly those with low income, disabilities or who work in informal employment.84 However, the lack of data on coverage creates difficulty in assessing whether the aims of microfinance translate into practice.83 While results demonstrate the overall positive impacts of microfinance, other studies highlight several factors which contribute towards the exclusion of people with disabilities.79 82 Exclusionary outcomes result from self-exclusion due to a lack of self-confidence; exclusion by others involved in group lending; exclusion by staff who provide loans; exclusion by design which prioritises higher educated and higher-income individuals; and physical or informational barriers.82 Beisland and Mersland suggest improving the design of microfinance schemes, introducing more flexibility to loan conditions and repayment plans.85 However, microfinance schemes may not be accessible for those with severe impairments.

Non-contributory schemes: UCTs

Features of UCTs

The UCT schemes identified in this review can be divided into two categories: means-tested and non-means-tested schemes (online supplementary figure 1). A total of 91 studies identified 70 individual UCTs schemes across 54 countries, finding that 31 (44%) of these schemes targeted general poverty alleviation using a means-tested approach, with disability as a proxy for vulnerability. Meanwhile, the remaining 39 (56%) of schemes were tailored specifically for people with disabilities (online supplementary table 1). A second difference between UCT schemes pertains to the types of assessments used. Drawing from the data found in this review, the majority of non-means-tested schemes used healthcare workers to determine an applicant’s eligibility. Means-tested schemes generally relied on decentralised assessment protocols, using local community members to determine the eligible individuals and households in the community (online supplementary table 1).

The protective capacity of UCTs

UCTs were reported to reduce financial pressure on households, which in turn, reduced stress levels and improved food security and access to household amenities (table 2). However, the level of payment was consistently reported to be inadequate in meeting the full needs of individuals and their households (table 2). Furthermore, disability claimants can lose their benefits once their health improve, increasing the risk of falling back into poverty. This, in turn, could trigger a relapse in their health condition. As such, studies indicate that UCTs could encourage dependency and fail to lift people out of chronic poverty (table 2).

Table 2.

Benefits and limitations of UCT schemes

| Benefits | Outcome | Country |

| Increase ability to pay for household amenities | South Africa22 27 86 87; Ethiopia88 | |

| Reduction in stress levels | Malawi89; Zambia90 91; Mozambique, Yemen, Palestine92 | |

| Increase access to a nutritionally complete diet | South Africa23 93; Malawi24 Ethiopia88 | |

| Improved health status | South Africa22 23; Zambia94 Malawi95 | |

| An improvement in self-worth and independence | Zambia92 94 South Africa96 Yemen97 | |

| Limitations | Reversal of health outcomes if UCTs are rescinded | South Africa22 23 93 98 |

| Long-term recipients find difficulties in securing employment UCTs are recinded | South Africa99 | |

| Funds insufficient in reducing vulnerability, including meeting both healthcare, nutrition and household needs | South Africa,22 23 27 86 100–102 Zambia94 China,103 104 Peru36 Malawi,105 Vietnam106 | |

| Inability to save a surplus income creates long term dependency on UCTs | South Africa86 96 99 102 107–110 Brazil77 111 112; Malawi51 | |

| Majority of schemes include pre-existing poverty in the eligibility criteria and do not protect those who are vulnerable to poverty | Multiple (see 113–115) | |

| Funding levels do not recognise the nuance of different illnesses and the range of their respective costs. | Palestine116 |

UCTs, unconditional cash transfers.

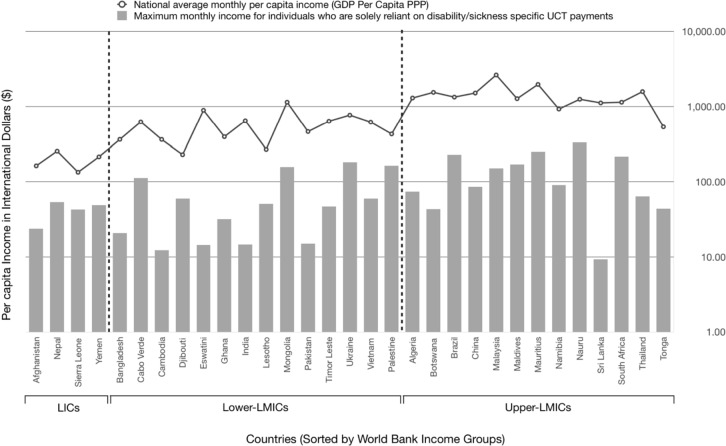

Equity in UCT schemes

When comparing the entitlements afforded to UCT recipients to the income of the average population, those who receive UCTs receive an income 10 times lower than the average per capita income (figure 4). Furthermore, there are significant variations in equity within populations who cannot work due to ill health. Severe disability benefits cover from as little as 0.1% up to 100% of the population who have disabilities. More significantly, however, the ILO does not have sufficient data on disability benefits in 73% of LMICs, and an absence of data on those with less severe disabilities.14 There are many factors which contribute towards poor coverage within populations, and primarily stem from the incorrect inclusion or exclusion of people who experience ill health (online supplementary table 3).

Figure 4.

Maximum amount of disability/sickness benefits available to eligible unconditional cash transfer (UCT) recipients per month, compared with the National average monthly per capita income (GDP per capita PPP) in selected low-income and middle-income countries (presented using a logarithmic scale). Sources: Brazil, India,118; Ukraine119; West bank & Gaza116; Yemen;97 other: Africa114; Asia & Pacific115; conversion resources.120 121LICs, low-income countries; MICs, middle-income countries; GDP, gross domestic product; PPP, purchasing power parity

Inclusion errors

Seven studies provided results on inclusion errors, which is a phenomenon whereby income support is provided to individuals who are not eligible for the scheme.20 104 122–126 Mitra109 reported a 34% inclusion error rate in South Africa, attributing this to the wrongful inclusion of persons without disabilities during the assessment process.109 Two studies report that some healthcare workers believe that they encounter large numbers of people who fabricate or exaggerate symptoms.122 127 Inconsistencies in welfare targeting were also identified in China, India and Pakistan. These errors are attributed to social factors, with the authors asserting that ‘well-connected’ applicants are more likely to win favour with politicians and community welfare assessors.123–126

Exclusion errors

Exclusion errors featured more prominently in the results of this review, with 46 studies discussing the circumstances in cases where eligible individuals were not in receipt of income support (online supplementary table 3). Sixty-one studies identified that 24 factors, reported in 29 countries, contributed towards high exclusion errors (online supplementary table 3). These errors were attributed to stigma, costs in applying for income protection, failures in the assessment process and the complexity of applying. Further, structural barriers also contributed toward exclusion errors, including problems of underfunding, poorly organised administration, corruption and the systemic exclusion of marginalised groups (online supplementary table 3).

Moral hazard

Individuals may be less likely to safeguard against risks when protected from their consequences.128 129 Several studies speculate that recipients of South Africa’s Disability Grant alter their behaviour when insured, leading to moral hazard. One study hypothesised that financial support impacted adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), leading people to ‘stay sick’ in order to receive an income.98 However, Woolgar and Mayers23 found that recipients would remain adherent to ART despite the risk of losing a grant.22 23 Additionally, Møller’s investigation of this ‘perverse incentive’ for youth to contract tuberculosis was inconclusive.96 Lastly, respondents in South Africa stated that finding work was considered preferable to receiving a social grant,107 112 with Goudge and Ngoma93 adding that, while people can get sick after losing the grant, poverty and malnourishment may instead be the cause of ex-recipients' deterioration in health.93

Discussion

Despite significant gaps in data, the results of this review provide an overview of the range of policies that exist in LMICs, and their potential benefits. However, a significant number of limitations remain. Indeed, while a number of weaknesses are associated with specific policies, the patterns and themes uncovered in this review provide a collective insight into the landscape of social protection and reveal systemic barriers that inhibit the efficacy and equity of protective interventions.

Protective capacity of income security

There is very limited evidence on whether income support in its present form meets the needs of the claimant.125 Research on UCTs and microfinance has garnered the most research, indicating strengths and weaknesses in the level of income support provided. Nine studies on 10 countries reported that UCT programmes were underfunded and resulted in inadequate support and long delays in payments (online supplementary table 3). Studies on microfinance demonstrated that it can protect against financial shocks.81 83 However, this draws on a small sample of nine studies, and cannot be reflective of all schemes.

Research on sickness benefits, injury compensation and general social insurance is even more inconclusive, largely owing to the absence of data on the subject. While the ILO present data on legal coverage, little is known on the level of payments that are made, and whether payments meet the level of need. Indeed, the ILO concede that there is no effective monitoring in place to see for example if injured workers are effectively compensated by their employers.14 Additionally, data on the minimum legal entitlements for workers do not assess whether these entitlements can sufficiently cover household expenses. Ultimately, therefore, further research is needed to understand the sufficiency of protective measures relating to sickness benefits, injury compensation, social insurance in general and UCTs.

Equity in income security

Beginning from a policy perspective, the eligibility criteria establishes a fragmented picture, leaving gaps in coverage for those in need. For instance, those suffering from short-term illnesses are heavily reliant on social insurance schemes, yet those who are informally employed cannot always access these privileges. Herein lies the first gap, which separates the short-term health entitlements of those with and without basic workers′ rights.

Building on this, the distinction between short-term and long-term illness seems to have been universally ignored in policy-making spaces, leaving an absence of any universal standard that defines these states of being. This conclusion does not mean to negate the value of the ICF model,19 yet, in practice, the fragmented nature of income security policies has ruptured the spectrum on which ill health occurs, boxing short-term and long-term illnesses into separate, yet blurred, policy spaces.

This is most evident in the context of UCTs, which primarily aim to protect the most vulnerable in society. However, this review has shown the application process of obtaining income support can be a slow, confusing and time-consuming process, with conflicting interpretations made by healthcare professionals on who is eligible for support.108 127 As such, the second gap occurs. Those who have short-term illnesses, work informally, are typically poorer and in greater need of income support, are, in practice, ineligible for UCTs owing to the time it takes to apply. Within this time, they may have recovered from their illness but are left burdened financially, owing to lost wages in the time it has taken to recover.

The third gap pertains exclusively to long-term illnesses, which in many contexts, remains equally fragmented. For instance, some UCTs require a minimum length of time before a person is deemed to have a disability, regardless of their medical diagnosis.14 47 Other schemes have what is effectively an ‘expiry date’ whereby individuals lose their welfare entitlements after a certain number of years.66 Further, many countries exclude potential recipients, either on the basis of the type of illness or the severity.14 36 114 115 130 Lastly, of the 70 UCT schemes identified in this review, 49 (70%) stipulated that a claimant with a disability must already live in poverty (online supplementary material 1; 113–115 131 132). Here again, gaps emerge, with people experiencing a moderate degree of incapacity and those vulnerable to poverty, being excluded from income security schemes. Consequently, several studies highlight the importance of diversifying income security programmes, to offer a range of income-supporting and income-generating options, which meet the needs of a broader pool of recipients.22 23 99 133 134

This study presents several limitations. First, by excluding studies that are not published in English, this study cannot claim to include all relevant literature on this topic. Second, manually reviewing the data increases the risk of human error, meaning that relevant literature may have been overlooked.39 The use of a formalised scoping review aimed to mitigate this risk and the iterative nature of a scoping review allows for the expansion of the search parameters. Although this investigation has included non-peer-reviewed studies, any unqualified statements have been noted and compared with similar studies, to illustrate inconsistencies. Lastly, the data extracted from this body of research derive from a variety of contexts. Therefore, the data in this review are not standardised in nature, nor can individual studies provide exact answers to our research questions. Instead, this review provides an exploratory overview of the landscape of income security, using the body of literature as a whole to highlight the main themes, patterns and gaps within social protection research.

Conclusion

This review marks a first step towards synthesising information on income security for individuals in LMICs who experience ill health. In doing so, it has identified significant inequalities in the level of income support and coverage across and within LMICs, specifically in regard to sickness benefits, injury compensation, social insurance, microfinance and UCTs.14 This review demonstrates the need for a greater understanding of the circumstances of those who cannot work due to ill heath, to improve the equity and coverage of income security in LMICs.

The small number of studies in LMICs is in itself a significant finding, showing that the topic has received very limited attention in countries where it is of major importance. Moving forward, further research is crucial in contributing towards a better understanding of how to reach the SDGs, particularly goals 1, 3, 8 and 10, which advocate for the eradication of poverty, good health and well-being, decent work and reduced inequalities.1 More specifically, further investigation into coverage, protective effects, equity and operational challenges must involve the study of all forms of sickness-related income loss and account for the changing landscape of global health and labour market transition.135 In order to foster intersectoral approaches for financial risk protection for people struck by ill health, research on income security needs to become a more visible part of the UHC research and policy agenda. Without valuable input from the health sector, the true understanding of illness-related costs and the corresponding scalability, equity and fiscal space to develop protective interventions will remain limited.

Ultimately, more research in this field could inform a number of evidence-based interventions, including better enforcement of labour regulations, improving access to social insurance, developing more diverse or integrated contributory and non-contributory schemes, and improving rehabilitation and work opportunities for people with disabilities.99 119 In turn, greater understanding of these topics will better inform spending decisions to improve financial sustainability and institutional capacity.136 In doing so, further research and recognition may ultimately elevate the role of income security and generate equitable policies which can serve a universally protective and productive function.137 138

Footnotes

Handling editor: Soumitra S Bhuyan

Contributors: All authors conceptualised the paper. JT performed the search and data extraction and analysed the data with assistance from KV, GH and KL. JT wrote the first draft. All authors contributed the finalisation of the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors are members of the Health and Social Protection Action Research & Knowledge Sharing network (SPARKS), an international interdisciplinary research network. SPARKS’ multisectoral team characterises and evaluates the direct and indirect effects of social protection strategies on health, economic and wider outcomes.

Funding: Funding for this research was received from the Swedish Research Council (2018–05174).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1.United Nations Final list of proposed sustainable Development Goal indicators [online]. United Nations, 2016: 2–25. (accessed 5 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Rio political Declaration social determinants of health. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Levelling up (Part 2): a discussion paper on European strategies for tackling social inequities in health. Studies on social and economic determinants of population health. 1, 2006: 2–124. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:817–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Together on the road to universal health coverage: A call to action [online. WHO Press, 2017. (accessed 28 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lönnroth K, Tessier L, Hensing G, et al. Income security in times of ill health – the next frontier of the SDGs. BMJ Global Health 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neelsen S, Limwattananon S, O'Donnell O, et al. Universal health coverage: a (social insurance) job half done? World Dev 2019;113:246–58. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiel-Adlung X. Revisiting policies to achieve progress towards universal health coverage in low-income countries: Realizing the pay-offs of national social protection floors. Int Soc Secur Rev 2013;66:145–70. 10.1111/issr.12022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lönnroth K, Glaziou P, Weil D, et al. Beyond UHC: monitoring health and social protection coverage in the context of tuberculosis care and prevention. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001693 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran BP, Hensing G, Thorpe J, et al. Income security during public health emergencies: the COVID-19 poverty trap in Vietnam. BMJ Global Health 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ILO & WHO Social Protection Floor Initiative Manual and Strategic Framework for joint UN Country Operations: the sixth initiative of the CEB on the global financial economic crisis and its impact on the work of the UN system. ILO & WHO: Geneva, 2009: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:817–908. 10.2471/blt.07.049403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ILO Economic security for a better world [online]. International Labour Organization, 2004. (accessed 29 January 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.ILO World social protection report 2017-2019: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals [online]. International Labour Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikman A, Marklund S, Alexanderson K. Illness, disease, and sickness absence: an empirical test of differences between concepts of ill health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:450–4. 10.1136/jech.2004.025346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster M. Medical Definition of ill-health [online]. Merriam Webster Incorporated: 2–19. (accessed 12 January 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrell-Carrio F, Schuman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. The Annals of Family Medicine 2004;2:576–82. 10.1370/afm.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham L, Moodley J, Ismail Z, et al. Poverty and disability in South Africa, research report 2014, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health ICF. WHO. : Geneva, 2002: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banks LM, Kuper H, Polack S. Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:2189996 10.1371/journal.pone.0189996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesliuc E, Pop L, Grosh M, et al. Income support for the poorest: A review of experience in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The World Bank, : Washington DC, 2014: 11–195. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Paoli M, Mills E, Grønningsæter A. The ARV roll out and the disability grant: a South African dilemma? J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15:6–10. 10.1186/1758-2652-15-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolgar HL, Mayers PM. The perceived benefit of the disability grant for persons living with HIV in an informal settlement community in the Western Cape, South Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2014;25:589–602. 10.1016/j.jana.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller C, Tsoka MG. ARVs and cash too: caring and supporting people living with HIV/AIDS with the Malawi social cash transfer. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:204–10. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiel-Adlung X, Sandner L. Paid sick leave: incidence, patterns and expenditure in times of crisis. International labour organization. Working paper No.27, 2010: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ICRC Cash transfer programming in armed conflict: the ICRC’s experience [online]. International Committee of the Red Cross, 2019. (accessed 9 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham L, Moodley J, Selipsky L. The disability–poverty nexus and the case for a capabilities approach: evidence from Johannesburg, South Africa. Disabil Soc 2013;28:324–37. 10.1080/09687599.2012.710011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benzeval M, Bond L, Campbell M, et al. How does money influence health? Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2015:2–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Labour Organization Introduction: Social Transfers [online]. International Labour Organisation, 2018. (accessed 1 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrientos A, Hinojosa-Valencia L. A review of social protection in Latin America. Brooks World Poverty Institute: Manchester, 2009: 2–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camacho A, Conover E, Hoyos A. Effects of Colombia’s Social Protection System on Workers’ Choice between Formal and Informal Employment. The World Bank. Working Paper, 2013: 6564. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slater R. Cash transfers, social protection and poverty reduction. overseas development Institute. Working paper, 2011: 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doetinchem O, Xu K, Carrin G. Technical briefs for policymakers no.1: Conditional cash transfers - what’s in it for health? WHO Press 2008:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO Conditional cash transfers and nutritional status [online], 2019. (Accessed 12 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pega F, Walter S, Liu SY, et al. Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;21:CD011135 10.1002/14651858.CD011135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernabe-Ortiz A, Diez-Canseco F, Vasquez A, et al. Inclusion of persons with disabilities in systems of social protection: a population-based survey and case–control study in Peru. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011300–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuper H, Walsham M, Myamba F, et al. Social protection for people with disabilities in Tanzania: a mixed methods study. Oxford Development Studies 2016;44:441–57. 10.1080/13600818.2016.1213228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Joanna Briggs Institute The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015: 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foucault M. The Order of Discourse : Young R, Untying the text: a Post-Structuralist reader. Boston Massachusetts: Routledge Ltd, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmqvist G. Perspectives on inequality and social protection, Ph.D Thesis in Peace and Development Research, School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg. Gothenburg. Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitra S, Palmer M, Mont D, et al. Can households cope with health shocks in Vietnam? Health Econ 2016;25:888–907. 10.1002/hec.3196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toseva E, Stoyanova R, Turnovska T. Economic costs due to workers’ sick leave at wastewater treatment plants in Bulgaria. Med Pr 2018;69:129–41. 10.13075/mp.5893.00577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozkan UR. Welfare regime change - or lack of change - in unemployment compensation. Int J Soc Welf 2016;25:126–35. 10.1111/ijsw.12171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costa NR, Marcelino AM, Duarte CMR, et al. Social protection for people with disabilities in Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2016;21:3037–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siano AK, Ribeiro LC, Ribeiro MS. Concession of sickness benefit to social security beneficiaries due to mental disorders. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 2011;33:323–31. 10.1590/S1516-44462011000400004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simões T, Passalini P, Fuller R. Public social security burden of musculoskeletal diseases in Brasil- descriptive study 2018;64:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller CM, Tsoka M, Reichert K. Targeting cash to Malawi's Ultra-Poor: a mixed methods evaluation. Development Policy Review 2010;28:481–502. 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00493.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dias EC, Oliveira RPde, Machado JH, et al. Employment conditions and health inequities: a case study of Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2011;27:2452–60. 10.1590/S0102-311X2011001200016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.ILO Domestic workers in Thailand: their situation, challenges and the way forwards. ILO office for East Asia, Bangkok, 2010: 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 54.ILO Social protection assessment based national dialogue: towards a nationally defined social protection floor in Thailand. ILO, Bangkok, 2013: 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- 55.ILO & IFC Better work Haiti: 17th synthesis report under hope II legislation, 2018. a. (accessed 4 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmad N, Aggarwal K. Health shock, catastrophic expenditure and its consequences on welfare of the household engaged in informal sector. J Public Health 2017;25:611–24. 10.1007/s10389-017-0829-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang JIN, Qian J, Wen Z. Social protection for the informal sector in urban China: institutional constraints and self-selection behaviour. J Soc Policy 2018;47:335–57. 10.1017/S0047279417000563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khanal D. Social Security/ social protection in Nepal situation analysis. Kathmandu: ILO Country Office for Nepal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.ILO & IFC Better work Vietnam: Garment industry 8th compliance synthesis report. Geneva: ILO & IFC, 2015. (accessed 4 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 60.ILO & IFC Better Work Cambodia. Geneva: ILO & IFC, 2018. b. (accessed 4 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.ILO & IFC Better Work Bangladesh: An industry & compliance review. Geneva: ILO & IFC, 2019. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solinger DJ, Hu Y. Welfare, Wealth and Poverty in Urban China: The Dibao and Its Differential Disbursement. China Q 2012;211:741–64. 10.1017/S0305741012000835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trifković N. Spillover effects of international standards: working conditions in the Vietnamese SMEs. World Dev 2017;97:79–101. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Banks LM, Walsham M, Minh HV, et al. Access to social protection among people with disabilities: evidence from Viet Nam. Int Soc Secur Rev 2019;72:59–82. 10.1111/issr.12195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriques CU, Bialoborska M. Organization and representation of informal workers in São Tomé and Príncipe: state agency and sectoral informal alternatives. African Studies Quarterly 2017;17:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kongtip P, Nankongnab N, Chaikittiporn LW, et al. Informal workers in Thailand: occupational health and social security disparities. New Solutions 2015;25:189–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bošnjak N. Problems of the pension and disability insurance system in Bosnia and Herzegovina and possible directions of its reform. Eur J Multidisciplin Stud 2016;1:186–94. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Naagarajan R. Social security of informal sector workers in Coimbatore district, Tamil Nadu. Indian J Labour Econ 2010;53:360–80. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buitrago Echeverri MT, Abadía-Barrero CE, Granja Palacios C. Work-Related illness, work-related accidents, and lack of social security in Colombia. Soc Sci Med 2017;187:118–25. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ceritoğlu E. The impact of labour income risk on household saving decisions in turkey. Rev Econ Househ 2013;11:109–29. 10.1007/s11150-011-9137-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kabir H, Maple M, Usher K, et al. Health vulnerabilities of readymade garment (RMG) workers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:70 10.1186/s12889-019-6388-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng Z, Nielsen I, Smyth R. Access to social insurance in urban China: a comparative study of rural–urban and urban–urban migrants in Beijing. Habitat Int 2014;41:243–52. 10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao Q, Yang S, Li S. Labor contracts and social insurance participation among migrant workers in China. China Economic Review 2012;23:1195–205. 10.1016/j.chieco.2012.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.RNSF Extending coverage: social protection and the informal economy. experiences and ideas from researchers and practitioners. research, network and support facility, ARS Progetti, Rome; Lattanzio Avisory, Milan; and AGRER Brussels, 2017: 5–162. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tangcharoensathien V, Pitayarangsarit S, Patcharanarumol W, et al. Promoting universal financial protection: how the Thai universal coverage scheme was designed to ensure equity. Health Res Policy Sys 2013;11:1–9. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferreira FHG, Robalino D. Social protection in Latin America: achievements and limitations (working paper 5305). New York: World Bank, 2010: 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jaccoud LdeB, Mesquita ACS, Paiva ABde. Bpc: from security advances to the risk of social security reform. Cien Saude Colet 2017;22:3499–504. 10.1590/1413-812320172211.22412017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linnemayr S, Buzaalirwa L, Balya J, et al. A microfinance program targeting people living with HIV in Uganda: client characteristics and program impact. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2017;16:254–60. 10.1177/2325957416667485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cramm JM, Paauwe M, Finkenflügel H. Facilitators and hindrances in the experiences of Ugandans with and without disabilities when seeking access to microcredit schemes. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:2166–76. 10.3109/09638288.2012.681004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Government of Malawi Review of the Malawi national social support programme: a stakeholder driven review of the design and implementation of the Malawi national social support programme. Lilongwe, Malawi, 2016: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grugel J, Riggirozzi P. New directions in welfare: rights-based social policies in post-neoliberal Latin America. Third World Q 2018;39:527–43. 10.1080/01436597.2017.1392084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mersland R, Bwire FN, Mukasa G. Access to mainstream microfinance services for persons with Dis- abilities—lessons learned from Uganda. Disability Studies Quarterly 2009;29. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Isoto RE, Sam AG, Kraybill DS. Uninsured health shocks and agricultural productivity among rural households: the mitigating role of Micro-credit. J Dev Stud 2017;53:2050–66. 10.1080/00220388.2016.1262027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Government of Rwanda Vision 2020 Umurenge programme: annual report 2009/10. Kigali, Rwanda, 2011: 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beisland LA, Mersland R. Exploring microfinance clients with disabilities: a case study of an Ecuadorian microbank. J Dev Stud 2017;53:1929–43. 10.1080/00220388.2016.1265946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goudge J, Russell S, Gilson L, et al. Illness-Related impoverishment in rural South Africa: why does social protection work for some households but not others? J Int Dev 2009;21:231–51. 10.1002/jid.1550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steinert JI, Cluver L, Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. Relationships between poverty and AIDS illness in South Africa: an investigation of urban and rural households in KwaZulu-Natal. Glob Public Health 2017;12:1183–99. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1187191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rispel LC, De Sousa CADP, Molomo BG. Can social inclusion policies reduce health inequalities in sub-saharan Africa? - A rapid policy appraisal. J Health Popul Nutr 2009;27:492–504. 10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Angeles G, de Hoop J, Handa S, et al. Government of Malawi's unconditional cash transfer improves youth mental health. Soc Sci Med 2019;225:108–19. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Handa S, Natali L, Seidenfeld D, et al. Can unconditional cash transfers raise long-term living standards? Evidence from Zambia. J Dev Econ 2018;133:42–65. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hjelm L, Handa S, de Hoop J, et al. Poverty and perceived stress: evidence from two unconditional cash transfer programs in Zambia. Soc Sci Med 2017;177:110–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Samuels F, Stavropoulou M. ‘Being Able to Breathe Again’: The Effects of Cash Transfer Programmes on Psychosocial Wellbeing. J Dev Stud 2016;52:1099–114. 10.1080/00220388.2015.1134773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Goudge J, Ngoma B. Exploring antiretroviral treatment adherence in an urban setting in South Africa. J Public Health Policy 2011;32:S52–64. 10.1057/jphp.2011.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schneider M, Waliuya W, Munsanje J, et al. Reflections on including disability in social protection programmes. IDS Bull 2011;42:38–44. 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00271.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Owusu-Addo E, Renzaho AMN, Smith BJ. The impact of cash transfers on social determinants of health and health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:675–96. 10.1093/heapol/czy020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Møller V. Strengthening Intergenerational Solidarity in South Africa: Closing the Gaps in the Social Security System for Unemployed Youth—A Case Study of the “Perverse Incentive”. J Intergener Relatsh 2010;8:145–60. 10.1080/15350771003745114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bagash Transforming cash transfers: beneficiary and community perspectives on the social welfare fund in Yemen 2012.

- 98.Azia IN, Mukumbang FC, Van Wyk B. Barriers to adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a regional hospital in Vredenburg, Western Cape, South Africa. South Afr J HIV Med 2016;17:1–8. 10.4102/sajhivmed.v17i1.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Engelbrecht M, Lorenzo T. Exploring the tensions of sustaining economic empowerment of persons with disabilities through open labour market employment in the Cape Metropole. South African J Occupation Ther 2010;40:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gender GB. Rights and the disability grant in South Africa. Dev South Afr 2009;26:369–82. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hussey M, MacLachlan M, Mji G. Barriers to the implementation of the health and rehabilitation articles of the United nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities in South Africa. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:117–9. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Plagerson S, Patel L, Hochfeld T, et al. Social policy in South Africa: Navigating the route to social development. World Dev 2019;113:1–9. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gao Q, Garfinkel I, Zhai F. Anti-poverty effectiveness of the minimum living standard assistance policy in urban China. Rev Income Wealth 2009;55:630–55. 10.1111/j.1475-4991.2009.00334.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Golan J, Sicular T, Umapathi N. Unconditional cash transfers in China: who benefits from the rural minimum living standard guarantee (Dibao) program? World Dev 2017;93:316–36. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brugh K, Angeles G, Mvula P, et al. Impacts of the Malawi social cash transfer program on household food and nutrition security. Food Policy 2018;76:19–32. 10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Palmer M, Groce N, Mont D, et al. The economic lives of people with disabilities in Vietnam. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133623–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Adams F, de Witt P, Franzsen D, et al. Livelihoods of youths with and without disabilities in peri-urban South Africa. South African J Occupation Ther 2014;44:509–19. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Phaswana-Mafuya N, Peltzer K, Petros G. Disability grant for people living with HIV/AIDS in the eastern Cape of South Africa. Soc Work Health Care 2009;48:533–50. 10.1080/00981380802595156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mitra S. Disability cash transfers in the context of poverty and unemployment: the case of South Africa. World Dev 2010;38:1692–709. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wright SCD. Persons living on a disability grant in Mpumalanga Province: an insider perspective. Curationis 2015;38:1–7. 10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Duarte CMR, Marcelino MA, Boccolini CS, et al. Social protection and public policy for vulnerable populations: an assessment of the continuous cash benefit program of welfare in Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 2017;22:3512–26. 10.1590/1413-812320172211.22092017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Neves-Silva P, Prais FG, Silveira AM. The inclusion of disabled persons in the labor market in Belo horizonte, Brazil: scenario and perspective. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2015;20:2549–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Burr L, Salimo P. The political economy of social protection in Mozambique. ESID working paper No.103. Manchester UK: University of Manchester, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cirillo C, Tebaldi R. Social protection in Africa: inventory of Non-contributory programmes 2016. (accessed 5 May 2019).

- 115.Tebaldi R, Cama T, Gwavuya S, et al. Social protection in Asia and the Pacific: Inventory of non-contributory programmes. pp.18–255. [online] 2019. (accessed 5 May 2019).

- 116.Abu Hamad B, Pavanello S. Transforming cash transfers: beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian national cash transfer programme. Part 1: the case ofthe Gaza strip. London Overseas Development Institute 2012:1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Palmer M. Social protection and disability: a call for action. Oxford Development Studies 2013;41:139–54. 10.1080/13600818.2012.746295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gooding K, Marriot A. Including persons with disabilities in social cash transfer programmes in developing countries. J Int Dev 2009;21:685–98. 10.1002/jid.1597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Melnyk OG. State support of people with disabilities in Ukraine. Scientific Bulletin of Polssia 2016;4:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 120.World Bank Gdp per capita, ppp (current international $), 2018. b. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD [Accessed 9 March 2019].

- 121.World Bank Ppp conversion factor, private consumption (LCU per international dollar), 2018. c. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PRVT.PP [Accessed 9 March 2019].

- 122.Kelly G. Patient agency and contested notions of disability in social assistance applications in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2017;175:109–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Haseeb M, Vyborny K. Imposing institutions: evidence from cash transfer reform in Pakistan. centre for the study of African economies, University of Oxford 2016.

- 124.Mishra AK, Kar A. Are targeted unconditional cash transfers effective? Evidence from a poor region in India. Soc Indic Res 2017;130:819–43. 10.1007/s11205-015-1187-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nguyen MTN, Chen M. The caring state? on rural welfare governance in post-reform Vietnam and China. Ethics and Social Welfare 2017;11:230–47. 10.1080/17496535.2017.1300307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sarwar MB. The political economy of cash transfer programmes in Brazil, Pakistan and the Philippines When do governments ‘leave no one behind’? ODI 2018;543:7–36. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Figueredo R, Damas FB. Psychiatric legal investigation for sickness benefits due to disability at the Brazilian federal social security special court in Florianópolis, capital city of the state of SANTA Catarina, southern Brazil. Trends in Psychiatry & Psychotherapy 2015;32:82–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Einav L, Finkelstein A. Moral hazard in health insurance: what we know and how we know it. J Eur Econ Assoc 2018;16:957–82. 10.1093/jeea/jvy017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Khan J, Rehnberg C. Perceived job security and sickness absence: a study on moral hazard. Eur J Health Econ 2009;10:421–8. 10.1007/s10198-009-0146-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Carpenter S, Slater R, Mallet R. Social protection and basic services in fragile and conflict-affected situations. secure Livelihoods research Consortium 2012. Contract No.:8.

- 131.Ortiz I, Schmitt V, De L. Social protection floors: volume 1: universal schemes. Geneva: ILO, 2016: 107–61. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Drucza K. Social protection Policymaking in Nepal. J Soc Res Pol 2015;6:33–5. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Govender V, Fried J, Birch S, et al. Disability grant: a precarious lifeline for HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:1–10. 10.1186/s12913-015-0870-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Preotesi M. Groups and needs: response of the social protection system in nowadays Romania. Revista de Cercetare is Intervene sociala 2016;55:139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 135.ILO Work for a Brighter Future - Global Commission on the Future of Work. 71 Geneva: ILO, 2019: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Niño-Zarazúa M, Barrientos A, Hickey S, et al. Social protection in sub-Saharan Africa: getting the politics right. World Dev 2012;40:163–76. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ocampo JA, Gómez-Arteaga N. Social protection systems in Latin America: an assessment (working paper No.52). Geneva: ILO, 2016: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tillin L, Duckett J. The politics of social policy: welfare expansion in Brazil, China, India and South Africa in comparative perspective. Commonw Comp Polit 2017;55:253–77. 10.1080/14662043.2017.1327925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kongshøj K. The Chinese dream of a more progressive welfare state: progress and challenges. Fudan J Hum Soc Sci 2015;8:571–83. 10.1007/s40647-015-0100-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Khan F, Amatya B, Avirmed B, et al. Who global disability action plan: the Mongolian perspective. J Rehab Med 2018;50:358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Opoku MP, Nketsia W, Agyei-Okyere E, et al. Extending social protection to persons with disabilities: exploring the accessibility and the impact of the disability fund on the lives of persons with disabilities in Ghana. Glob Soc Policy 2019;19:225–45. 10.1177/1468018118818275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.ILO Review of the Malawi National Social Support Programme: A stakeholder driven review of the design and implementation of the Malawi National Social Support Programme (2012-2016) [online] 2016:5–58.

- 143.Vaitsman J, Lobato LVC. Continuous cash benefit (BCP) for disabled individuals: access barriers and intersectoral gap. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2017;22:3527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jones N, Shaheen M. Transforming cash transfers: beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian national cash transfer programme. Part 2: the case of the West bank. London Overseas Development Institute 2012:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Androniceanu A. Improving citizens satisfaction concerning the social welfare services at urban level. Theoretical & Empirical Researches in Urban Management 2017;12:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Costa NdoR. Street-level bureaucracy and social policy in Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 2017;22:3505–14. 10.1590/1413-812320172211.19952017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.NPC Assessment of social security allowance in Nepal. Singh Durbar, Kathamandu, Nepal: National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Selvester K, Fidalgo L, Taimo N. Transforming cash transfers: beneficiary and community perspectives on base social subsidy programme in Mozambique. London overseas development Institute 2012:1–53.

- 149.Holmes R, Uphadaya S. The role of cash transfers in post-conflict Nepal. London: London Overseas Development Institute, 2009: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chichaya TF, Joubert RWE, Ann McColl M. Analysing disability policy in Namibia: an occupational justice perspective. Afr J Disabil 2018. a;7:a1401. 10.4102/ajod.v7i0.401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Chichaya TF. Voices on disability in Namibia: evidence for entrenching occupational justice in disability policy formation. Scandinavian J Occupation Ther 2018. b;19:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shumba TW, Moodley I. Implementation of disability policy framework in Namibia: a qualitative study. S Afr J Physiother 2018. a;74:a400. 10.4102/sajp.v74i1.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Shumba TW, Moodley I. Review of policy and legislative framework for disability services in Namibia. S Afr J Physiother 2018. b;74:a339. 10.4102/sajp.v74i1.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hanass-Hancock J, McKenzie TC. People with disabilities and income-related social protection measures in South Africa: where is the gap? Afr J Disabil 2017;6:1–11. 10.4102/ajod.v6i0.300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Roth M, Toma S. The plight of Romanian social protection: addressing the vulnerabilities and well-being in Romanian Roma families. The Int J Human Rights 2014;18:714–34. 10.1080/13642987.2014.944813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Banks LM, Mearkle R, Mactaggart I, et al. Disability and social protection programmes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Oxford Development Studies 2017;45:223–39. 10.1080/13600818.2016.1142960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Chinyoka I. Poverty, changing political regimes, and social cash transfers in Zimbabwe, 1980-2016. Working paper 2017/88. Tokyo: United Nations University, 2017: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Cecchini S, Filgueria F, Robles C. Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: a comparative review 2014:1–47.

- 159.Devereux European report on development: building social protection systems in southern Africa. Brighton: Centre for Social Protection, Institute of Development Studies, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Kwok SM, Tam D, Hanes R. An exploratory study into social welfare policies and social service delivery models for people with disabilities in China. Global Social Welfare 2018;5:155–65. 10.1007/s40609-016-0077-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Hanass-Hancock J, Nene S, Deghaye N, et al. ‘These are not luxuries, it is essential for access to life’: Disability related out-of-pocket costs as a driver of economic vulnerability in South Africa. Afr J Disabil 2017;6:1–10. 10.4102/ajod.v6i0.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Slater R. Cash transfers, social protection and poverty reduction. overseas development Institute 2011:5–34. Working Paper.

- 163.Mathende LT, Nhapi TG. The nexus of globalisation and global South social policy crafting: some Zimbabwean perspectives. J Pan Afr Stud 2018;12:499–515. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Huang Y, Guo F. Welfare programme participation and the wellbeing of Non-local rural migrants in metropolitan China: a social exclusion perspective. Soc Indic Res 2017;132:63–85. 10.1007/s11205-016-1329-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Lui J, Lui K, Huang Y. Transferring from the poor to the rich: examining regressive redistribution in Chinese social insurance programmes. Inte J Soc Wel 2016;25:199–210. [Google Scholar]

- 166.Jensen OC, Lucero-Prisno DE, Haarløv E, et al. Social security for seafarers globally. Int Marit Health 2013;64:33–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Bonnet F, Cichon M, Galian C, et al. Analysis of the Viet Nam national social protection strategy (2011– 2020) in the context of social protection floors objectives. A rapid assessment 2012. Working paper. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2020-002425supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002425supp002.pdf (130.2KB, pdf)