Abstract

Although graphene-based biosensors provid extreme sensitivity for the detection of atoms, gases, and biomolecules, the specificity of graphene biosensors to the target molecules requires surface decoration of graphene with bifunctional linkers such pyrene derivatives. Here, we demonstrate that the pyrene functionalization influences graphene’s electrical properties by yielding partial formation of bilayer graphene which was confirmed by Raman 2D spectrum. Based on this observation, we introduce quadratic fit analysis of the nonlinear electrical behavior of pyrene-functionalized graphene near the Dirac point. Compared to the conventional linear fit analysis of the transconductance at a distance from the Dirac point, the quadratic fit analysis of the nonlinear transconductance near the Dirac point increased the overall protein detection sensitivity by a factor of 5. Furthermore, we show that both pyrene linkers and gating voltage near the Dirac point play critical roles in sensitive and reliable detection of proteins’ biological activities with the graphene biosensors.

Keywords: graphene, Dirac point, transconductance, biosensors, lysozyme activity

Introduction

Graphene has been identified as one of the most attractive materials over the last few decades.1-4 It has shown great promise in many applications including electronics,5 energy storage,6 and sensor systems7 because of its unique physical, chemical, electrical, and mechanical properties. In particular, graphene-based field effect transistors (FETs) have been widely developed and suggested as attractive platforms for rapid and accurate detectors.8 For example, graphene FETs are used for detecting individual atoms,9-10 gases,11 chemicals,8 and small biomolecules including proteins12-19 and disease biomarkers.20 Additionally, recent studies demonstrated that the integration of graphene FETs with microfluidic systems provides the potential of portable, point-of-care devices for the quantitative detection and identification of cancer in its early stages.21-22

The operation of graphene FETs as biosensors was characterized by measuring several sensing parameters: (1) the Dirac point VCNP which is a charge neutral Fermi energy position and a measure of charge doping in graphene; (2) the charge carrier mobility μ which is a quantity describing how easily charge carriers move through the graphene channel; and (3) the gate voltage Vg dependent transconductance gm (= ∂I/∂Vg) which describes the total scattering of charge carriers in graphene. Adsorbates on graphene contribute to both doping of charge carriers in graphene and inducing charge carrier scattering, causing changes in VCNP and gm. Of these parameters, the variation of VCNP is sensitive enough to detect a single atomic adsorption per 1000 carbon atoms in graphene.10 Also, the electrical polarity and concentration of adsorbates on graphene determine the relationship between the electrical current I and the gate voltage Vg.9-10, 23-24

Despite graphene’s extraordinary sensitivity to adsorbates, nonspecific adsorption has been pointed out as a drawback for sensing specific target molecules. To enhance the specificity of graphene-based sensing, surface conjugation methods with bifunctional linker molecules have been introduced,8, 25-26 where one end of the linkers, such as aromatic molecules, strongly adheres to graphene via π – π interaction, and the other end, such as a carboxylic group, allows specific biochemical reactions with the target molecules. For example, pyrene phosphoramidite and pyrene butyric acid have been used to detect biomolecules and cancer biomarkers.20, 26-27

Although functionalization approaches enhance the specificity of the graphene FETs, the linker molecules influence the overall sensor sensitivity.20, 28-29 The structural similarity between graphene and aromatic pyrene and the π – π bonding between them modify the linear relationship between the current and gate voltage I(Vg) to nonlinear, implying that the transconductance gm no longer remains constant at all gate voltages. This observation suggests the partial formation of bilayer graphene (BLG) with the pyrene linkers. Indeed, graphene biosensors functionalized with pyrene derivatives revealed the electronic characteristics of BLG such as nonlinear I(Vg) behaviors far from the Dirac point and the broadened VCNP area.20, 29 Thus, conventional I(Vg) analysis using the linear fit method needs to be reexamined, in order to understand the sensing mechanisms and enhance both sensitivity and reliability of the graphene FETs functionalized with the pyrene linkers.

Here, we describe quadratic fit analysis near the Dirac point of graphene FETs functionalized with pyrene-maleimide linker molecules. Both Raman spectroscopy and electronic characteristics of the functionalized graphene revealed the partial formation of BLG. The quadratic analysis model enabled us to reliably fit BLG’s nonlinear transconductance near the Dirac point and increased the detection sensitivity by a factor of 5, as compared to the conventional linear analysis model. In addition, we present the remarkable roles of the pyrene linkers in preserving enzymatic activities of target proteins and the importance of the gating voltage near the Dirac point for detecting the protein activities.

Results and Discussion

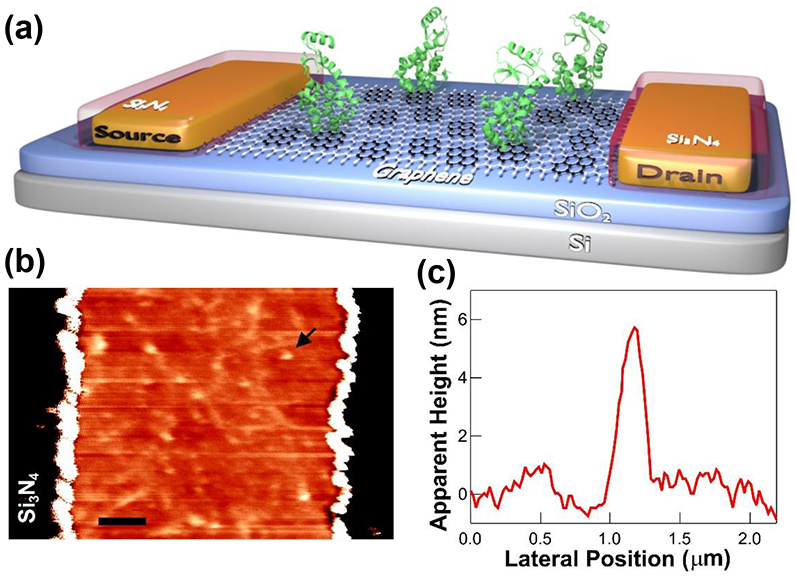

A schematic diagram of the graphene FETs is depicted in Figure 1a, in which a single layer of graphene (colored white) grown by chemical vapor deposition was connected to two metal terminals. A small bias of 100 mV was applied between the source and drain terminals, and then the source-drain current I was continuously recorded by varying gate bias Vg between drain and counter Pt electrode in a buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.5) solution. AFM images after functionalizing with the linker and lysozyme incubation show individual lysozymes covalently conjugated to pyrene-maleimide molecules (Figure 1b).25, 30 Lysozyme is 5 ~ 7 nm in height (Figure 1c), which is easily distinguishable when attached to graphene.

Figure 1.

Graphene field effect biosensors. (a) A schematic diagram of a graphene FET, where a layer of graphene, pyrene linkers, and lysozymes are colored in white, black, and green, respectively. (b) AFM image of a graphene device after bioconjugation with lysozymes (1 hr) through the linker molecules (The scale bar is 1 um). (c) AFM height profile of a single lysozyme (arrow in (b)).

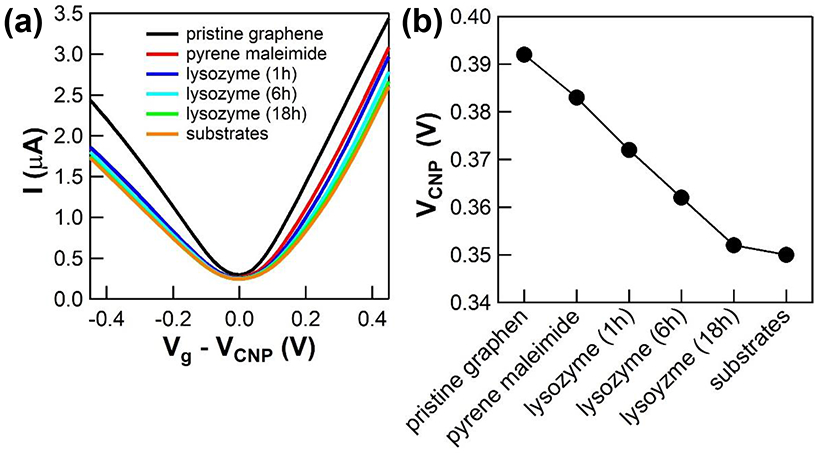

In ambient conditions, the average VCNP, μ, and two terminal resistance of the graphene FETs were 21.78 V ± 2.67 V, 4945 cm2/Vs ± 2000 cm2/Vs, and 5.945 kΩ ± 1.838 kΩ, respectively, indicating very high quality graphene with high consistency. Figure 2a shows the typical gate voltage dependence of the measured current I(Vg) of the liquid gated graphene FETs, demonstrating bipolar charge carriers around VCNP, where gm changes from negative (hole) to positive (electron). The I(Vg) curves show a significant shift of VCNP and gm at the subsequent functionalization of the linker molecules and bioconjugation of lysozyme steps.

Figure 2.

Electrical properties of the graphene FETs. (a) Representative I(Vg) curves of the pristine graphene FET and their shift induced by the functionalization of pyrene linkers and the bioconjugation of lysozyme with time. (b) The variation of VCNP due to the linker functionalization and protein bioconjugation steps, demonstrating the charge doping effects by the linker and lysozyme molecules.

The variation of VCNP values as a result of functionalization and bioconjugation is plotted in Figure 2b. When the pyrene linkers were functionalized, VCNP dropped ~ 10 mV, and additional conjugation of lysozyme further decreased VCNP values. It is known that aromatic molecules noncovalently functionalized on low dimensional carbon materials including carbon nanotubes and graphene donate their π electrons to the conduction band of the materials.20, 31-32 It is also reported that lysozyme is positively charged (+ 7e),33 and therefore the proximity of lysozyme dopes graphene with additional electrons. Thus, the decreased VCNP values are attributed to the charge gating effect of the attached linker molecules and lysozymes. However, the decrease of VCNP is not proportional to the incubation time of lysozymes (Note that Figure 2b is not scaled with time). Instead, the rate of overall charge gating by additional lysozymes decreases because of less accessible pyrene linkers and blocking by existing lysozymes. While the variation of VCNP shows no specificity to pyrene linkers and lysozyme, it could be used as a measure of charge doping in graphene, which could compliment other sensing parameters including transconductance associated with the scattering of charge carriers for the precise detection of target molecules using graphene FETs.

In addition to VCNP, changes in gm was examined after the linker functionalization and lysozyme conjugation. Initially, gm was extracted from the I(Vg) curves in Figure 2a by the linear fit model. Figure 3a shows the linear best-fit to the I(Vg) curve at a distance from VCNP and a short interval of ∣Vg - VCNP∣ from 0.15 V to 0.30 V, where the linear behaviors are associated with the Coulomb scattering of charge carriers.9-10, 34 However, the I(Vg) curve around VCNP (∣Vg - VCNP∣ < 0.15 V) is significantly off from the fit because of the charge transport mechanism associated with holes and electrons puddle around VCNP.34-35 Such trends were consistent throughout all functionalization and bioconjugation steps (Figures S1 - S2).

Figure 3.

The linear model of the I(Vg) curve. (a) The linear approximation fits well with both the negative (red line) and positive (blue line) slopes of the I(Vg) curve at a distance from VCNP. (b) The slope (±gm) obtained from the liner fit shows gradual changes in the pyrene functionalization and protein bioconjugation steps.

Changes in gm extracted from the linear fit show the overall decrease of < 30 % after functionalization and bioconjugation, though the absolute values of gm were slightly different due to the asymmetric I(Vg) (Figure 3b). The pyrene functionalization on graphene significantly reduced both ±gm values by 36 ~ 79 % of the overall gm changes, implying the strong scattering of charge carriers in graphene with the pyrene linkers. In contrast, lysozyme conjugation shows less effect on gm because charge carriers in graphene experience less scattering by the Coulomb interaction with lysozymes attached through the linkers at a distance from the graphene surface.

Although the linear fit model provides a useful parameter gm for biosensing, obtaining gm values are limited to the linear region of I(Vg) curves. Besides, the broadened the VCNP area along with lowered VCNP values and the nonlinear behavior of I(Vg) curves at a distance from VCNP by the pyrene functionalization process narrow window of the linear region and therefore make it difficult to consistently analyze gm with the linear fit model (Figures S3). In addition, sensing Vg at a distance from VCNP leads to two potential issues. First, the higher Vg could create unwanted electrochemical reactions such as water hydrolysis and oxidation of metal electrodes. Second, the noise incurred by pristine graphene in a solution increases as ∣Vg - VCNP∣ is increases.36

To address these issues, we investigated the nonlinear electrical properties of pyrene-functionalized graphene around VCNP. Considering that pyrene has the same atomic structure as graphene, it is reasonable to assume that single layer graphene (SLG) transformed to partial bilayer graphene (BLG) during the pyrene-maleimide functionalization process. To probe partial BLG formation, Raman spectra were obtained with the graphene FETs before and after functionalization of the pyrene linker molecules. The Raman spectrum of pristine graphene (Figure 4a) revealed a sharp single 2D peak with full width at half maximum (FWHM) < 30 cm−1, which is a standard SLG signal.37-38 However, the pyrene functionalization to graphene caused significant changes in the Raman spectrum (Figure 4b). The 2D peak deconvoluted into four sub Lorentzian peaks (blue curves), which increased the width of the 2D peak about 150 %. Such characteristics in Raman spectrum are the signature of BLG.39 Therefore, we concluded that the pyrene functionalization partially transforms pristine SLG to BLG.

Figure 4.

Raman spectra of the graphene FETs. (a) Raman spectrum of pristine graphene (black dot), showing a single 2D Lorentzian peak (red curve). (b) Raman spectrum of the same graphene after the functionalization of the pyrene linkers. The 2D peak was substantially broadened, and deconvoluted into four sub Lorentzian peaks (blue curve), indicating formation of BLG.

Because of different energy band structures, the electrical properties of BLG are much different from those of SLG. In BLG, the I(Vg) curves at a distance from VCNP are nonlinear depending on charge carrier concentration, i.e., I ~ Vgα (1 < α < 1.5), where α depends on charged impurity concentration.40-41 Therefore, gm extracted from the linear fit relying on the Vg and its fitting intervals is not a good parameter to describe sensing capability in BLG. To deal with such nonlinearity, we introduce a new sensing parameter based on the quadratic fit analysis of I(Vg), which is sensitive to disorders in BLG.

The conductivity σ of highly disordered BLG at the Fermi energy ε is described by42

| (1) |

where gν and gs are the valley and spin degeneracies, e is the elementary charge, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, εtrig is the trigonal wrapping energy, and Γ is the strength of disorder, respectively. Using the small ε approximation near VCNP, i.e., arctan(∣ε∣/Γ) ~ ∣ε∣/Γ, σ can be written as

| (2) |

From Ohm’s law, I through graphene is given by

| (3) |

where W and L are width and length of graphene, respectively, and Vsd is the source-drain bias voltage. Substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (3) gives

| (4) |

where m* is the effective mass. Thus, we obtain

| (5) |

where, and , respectively.

Equation (5) represents the quadratic relationship between I and Vg, in which slope b is inversely proportional to the adsorption of molecules (i.e., b ∝ 1/Γ2).42-43 Therefore, b (≡ gm(2)) could be a good sensing parameter for the BLG FETs.

The I(Vg) curves around VCNP were analyzed with the quadratic model to obtain gm(2). Upon functionalization of graphene with the pyrene linkers, the VCNP area became broadened and I(Vg) curves at a distance from VCNP became nonlinear as shown in Figure 2a. Thus, the I(Vg) curves fit perfectly by the Eq. (5) at the interval of Vg - VCNP from −0.1 V to 0.1 V (Figures 5a and S4 – S5), indicating partial formation of BLG. As a result, the gm(2) value was substantially decreased from 32.36 μS/V to 20.48 μS/V, which was 69 % of the overall Δgm(2) during the entire processes. The gm(2) values were further decreased by conjugation of lysozymes (Figure 5b and S6), which agrees with the fact that gm(2) is inversely proportional to disorders including charged impurities on BLG.42 Therefore, gm(2) is less sensitive to lysozyme conjugation than pyrene functionalization. The overall detection sensitivity obtained from gm(2) during the entire processes from pyrene functionalization to substrate introduction was increased by factor of 5, as compared to that of gm. Taken together, gm(2) can serve as a promising sensing parameter for the reliable detection of biomolecules in the graphene FETs.

Figure 5.

The nonlinear model of the I(Vg) curve. (a) The quadratic approximation perfectly fits with the I(Vg) curve around VCNP area. (b) The fitting parameter (gm(2)) obtained from the nonlinear model shows significant changes corresponding to the linker functionalization and protein bioconjugation steps.

Finally, we discuss the importance of the pyrene linkers and the gating voltage near the Dirac point to the detection of protein activities and functions. In this work, we have used a model enzyme lysozyme because it has shown excellent stability, consistent activity, and well defined conformational motions (~ 8 Å) during the hydrolysis of its substrates for a long period of measured time (Figure S7).30 Additionally, lysozyme provides a single thiol for conjugation to the pyrene-linked maleimide. ∆I(t) of lysozyme conjugated devices in the buffer solution was monitored by varying Vg. Figure 6a shows the typical ∆I(t) of the devices monitored at Vg = VCNP in the absence of the peptidoglycan substrates. After introducing the substrates in the buffer solution, ∆I(t) exhibited stochastic spikes above the mean baseline current (Figure 6b). Such ∆I(t) fluctuation is a signature of the hinge-bending motion of lysozyme processing its substrates, which has been well characterized by previous single lysozyme studies.25, 44 Although ∆I(t) fluctuations were not quantitatively determined like single molecule measurements, independent periodic motions of individual lysozymes contribute to the spikes in ∆I(t). Thus, the spikes can be ascribed to the lysozyme’s charge gating effects on the charge carriers in graphene.

Figure 6.

Monitoring lysozyme activities. (a) I(t) measurements of lysozyme conjugated graphene FETs without the peptidoglycan substrates. (b) I(t) measurements of the same device after introducing the substrates, revealing stochastic current spikes. (c) Histogram of ΔI(t) obtained at Vg = VCNP in the absence of the substrates (black dots), showing a Gaussian distribution (red curve). (d) After introducing the substrates, ΔI(t) histogram obtained at Vg = VCNP shows an extra peak (blue curve) caused by substrate-induced conformational changes of lysozyme from open to closed states. (e) Histogram of ΔI(t) obtained at Vg = 0.3 V demonstrates a wide noise distribution (σ = 5.88 nA) compared to that of ΔI(t) histogram obtained at Vg = VCNP (σ = 5.06 nA). (f) After introducing the substrates, the ΔI(t) histogram obtained at Vg = 0.3 V was broadened with two sub Gaussian distributions. However, those distributions were substantially overlapped due to the additional intrinsic noise at Vg = 0.3 V.

This conclusion is further supported by control measurements performed with the devices that were incubated with lysozymes in the absence of the linker molecules. The randomly and nonspecifically attached lysozymes on graphene did not yield any meaningful ∆I(t) spikes in the presence of the substrates (Figure S8), but demonstrated random signals similar to Figure 5a. These results emphasize that the linker molecules play a significant role in properly conjugating proteins as well as preserving their biological activities on the graphene FETs.45

To evaluate the distribution of the spike signals, histograms of ∆I(t) at the Dirac point and far from the Dirac point were generated from more than 120 s recordings. In the absence of the substrates, the ∆I(t) histogram fits well to a Gaussian distribution with a single deviation σ, indicating the random fluctuations of lysozymes (Figure 6c and 6e). When the substrates were introduced, the histogram was skewed, resulting in two Gaussian peaks associated with lysozyme’s open and closed conformations (Figure 6d and 6f). Of those, the Gaussian fit to the minor shoulder peak was resulted from the spikes of the higher current induced by substrate-induced, mechanical motions of lysozymes. Such observations indicate that pyrene linker molecules allow not only lysozyme detection but also enzymatic activities of lysozyme.

Next, ∆I(t) measurements were performed Vg (= 0.3 V) at a distance from VCNP. Similar to the Vg = VCNP case, the ∆I(t) histogram without the substrates produced a single Gaussian noise characteristic (Figure 6e). However, the noise deviation σ was increased by 16 %, indicating wider distribution of the device noise at a distance from VCNP.36 In the presence of the substrates, two peaks appeared due to the lysozyme actions (Figure 6f). Although ∆I between the two states remained almost the same, the deviation of each state, σ1 and σ2, compared to σ1 and σ2 in Figure 6d, was increased by 29 % and 54 % respectively. Such increased σ1 and σ2 substantially broaden both distributions, making them almost indistinguishable. These results highlight the importance of selecting Vg to detect protein activities and increase the detection sensitivity of the graphene FETs.

Conclusions

The results presented here provide an effective and sensitive method for biomolecule detection using graphene FETs when graphene is functionalized with the pyrene derivative linker molecules. The surface functionalization partially transformed the graphene structure from SLG to BLG, resulting in a nonlinear behavior of transconductance. We demonstrated that the new sensing parameter gm(2) determined by the quadratic fit model around VCNP can serve as a promising and alternative parameter for biomolecule detection with high sensitivity. Additionally, we showed that the pyrene linkers and the gating voltage near the Dirac point play important roles in the detection of target biomolecules and the preservation of their biological functions.

Experimental Section

Protein expression and purification.

A pseudo wild-type T4 lysozyme mutant (C54T/C97A/S90C) was synthesized via site-directed mutagenesis and expressed from Escherichia coli cells as previously described.30, 46 The purity of the expressed mutant was confirmed with gel-electrophoresis. The secondary structure of the mutant was confirmed with Circular Dichroism. The mutant was also confirmed to be functionally active with the commercial activity kit (Micrococcus lysodeikticus, ATCC No. 4698, Sigma-Aldrich), showing similar catalytic efficiency as compared to the wild-type protein.

Device fabrication.

Graphene was grown via chemical vapor deposition, and graphene field effect transistors were fabricated via optical and electron beam lithography as described previously.47-48 The graphene in the devices was covered by gold thin films to protect from ambient molecules. Prior to use, the films were etched by soaking in gold etchant (Gold Etchant Type TFA, TRANSENE Company, Inc.) for 5 minutes followed by sonication in acetone. Individual devices were electrically probed and imaged by atomic force microscopy to verify that the graphene is free of particulates.

Device functionalization.

Fresh graphene biosensors were functionalized using a bifunctional linker, pyrene-maleimide. The pyrene functionality adheres to the surface of graphene strongly via π – π stacking. The maleimide group can form stable thioether bonds with the free thiol of a cysteine sidechain in the protein. A solution of N-(1-pyrenyl)maleimide (Sigma Aldrich) in ethanol (1 mM) was prepared. Devices were soaked in solution for 30 min without agitation, and then washed with ethanol and de-ionized water for 5 min to remove excess pyrene-maleimide.

Protein conjugation.

A solution of T4 lysozyme (5.4 μM) prepared as described above in the buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.5) was used for bioconjugation. At room temperature, pyrene-maleimide-derivatized devices were soaked in the lysozyme solution up to 18 hours in a sealed container. Following conjugation, devices were stored in the buffer and neither dried nor imaged until the completion of measurements.

Device measurements.

All electronic measurements were performed with the active portion of the device submerged in the buffer solution. The potential of the electrolyte was controlled using Pt counter and pseudo-reference electrodes, and swept between −500 mV and 500 mV vs. Pt using a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter. The source-drain bias was held at 100 mV. A Keithley 428 preamplifier operating at 106 ~ 106 V/A gain was used to measure the source-drain current of the device. Data was collected for at least 300 s for each measurement condition. The analysis has been performed using a 10-Hz, digital low pass filter to ΔI(t) from I(t).

Raman spectroscopy.

Raman spectra of pristine graphene and pyrene-maleimide functionalized graphene FET devices were acquired using 533 nm excitation laser (Horiba). The spectra were obtained from 10 points in both devices.

AFM imaging.

The devices were imaged using a commercial atomic force microscope (NT-MDT NTEGRA). Prior to the imaging, the devices were dried by flowing nitrogen gas for 5 min. The semi-contact mode AFM measurements were performed under ambient conditions with AFM probes of resonant frequency 150 – 300 kHz (Budget sensors). The images were flattened to eliminate the background noise and tilt from the surface using all unmasked portion of scan lines to calculate individual least-square fit polynomials for each line.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported financially by the NIH/NIGMS under Award Number R15GM122063 and P20GM109024 and NSF/ND EPSCoR DDA and Seed awards.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Additional linear and nonlinear fit data, AFM images of the devices, enzyme activity assay, and control electronic measurements of the devices

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Yu X; Cheng H; Zhang M; Zhao Y; Qu L; Shi G Graphene-based smart materials. Nature Reviews Materials 2017, 2 (9), 17046, DOI: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Geim AK; Novoselov KS The rise of graphene. Nat Mater 2007, 6 (3), 183–191, DOI: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Geim AK Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science 2009, 324 (5934), 1530, DOI: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shao Y; Wang J; Wu H; Liu J; Aksay IA; Lin Y Graphene Based Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors: A Review. Electroanalysis 2010, 22 (10), 1027–1036, DOI: 10.1002/elan.200900571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Jessen BS; Gammelgaard L; Thomsen MR; Mackenzie DMA; Thomsen JD; Caridad JM; Duegaard E; Watanabe K; Taniguchi T; Booth TJ; Pedersen TG; Jauho A-P; Bøggild P Lithographic band structure engineering of graphene. Nature Nanotechnology 2019, 14 (4), 340–346, DOI: 10.1038/s41565-019-0376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Stoller MD; Park S; Zhu Y; An J; Ruoff RS Graphene-Based Ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8 (10), 3498–3502, DOI: 10.1021/nl802558y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Drndić M Sequencing with graphene pores. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9 (10), 743–743, DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2014.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Jiang S; Cheng R; Wang X; Xue T; Liu Y; Nel A; Huang Y; Duan X Real-time electrical detection of nitric oxide in biological systems with sub-nanomolar sensitivity. Nature Communications 2013, 4 (1), 2225, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen JH; Jang C; Adam S; Fuhrer MS; Williams ED; Ishigami M Charged-impurity scattering in graphene. Nat Phys 2008, 4 (5), 377–381, DOI: 10.1038/nphys935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Woo S; Hemmatiyan S; Morrison TD; Rathnayaka KDD; Lyuksyutov IF; Naugle DG Temperature-dependent transport properties of graphene decorated by alkali metal adatoms (Li, K). Appl Phys Lett 2017, 111 (26), 263502, DOI: Artn 263502 10.1063/1.5001080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Schedin F; Geim AK; Morozov SV; Hill EW; Blake P; Katsnelson MI; Novoselov KS Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nat Mater 2007, 6 (9), 652–655, DOI: 10.1038/nmat1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chung C; Kim Y-K; Shin D; Ryoo S-R; Hong BH; Min D-H Biomedical Applications of Graphene and Graphene Oxide. Accounts Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (10), 2211–2224, DOI: 10.1021/ar300159f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Beminger T; Bliem C; Piccinini E; Azzaroni O; Knoll W Cascading reaction of arginase and urease on a graphene-based FET for ultrasensitive, real-time detection of arginine. Biosens Bioelectron 2018, 115, 104–110, DOI: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Fenoy GE; Marmisolle WA; Azzaroni O; Knoll W Acetylcholine biosensor based on the electrochemical functionalization of graphene field-effect transistors. Biosens Bioelectron 2020, 148, DOI: ARTN 111796 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Piecinini E; Bliem C; Reiner-Rozman C; Battaglini F; Azzaroni O; Knoll W Enzyme-polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies on reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors for biosensing applications. Biosens Bioelectron 2017, 92, 661–667, DOI: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sohn IY; Kim DJ; Jung JH; Yoon OJ; Thanh TN; Quang TT; Lee NE pH sensing characteristics and biosensing application of solution-gated reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors. Biosens Bioelectron 2013, 45, 70–76, DOI: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Xu SC; Jiang SZ; Zhang C; Yue WW; Zou Y; Wang GY; Liu HL; Zhang XM; Li MZ; Zhu ZS; Wang JH Ultrasensitive label-free detection of DNA hybridization by sapphire-based graphene field-effect transistor biosensor. Appl Surf Sci 2018, 427, 1114–1119, DOI: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Xu SC; Zhan J; Man BY; Jiang SZ; Yue WW; Gao SB; Guo CG; Liu HP; Li ZH; Wang JH; Zhou YQ Real-time reliable determination of binding kinetics of DNA hybridization using a multi-channel graphene biosensor. Nature Communications 2017, 8, DOI: ARTN 14902 10.1038/ncomms14902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Xu SC; Zhang C; Jiang SZ; Hu GD; Li XY; Zou Y; Liu HP; Li J; Li ZH; Wang XX; Li MZ; Wang JH Graphene foam field-effect transistor for ultra-sensitive label-free detection of ATP. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 2019, 284, 125–133, DOI: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.12.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gao N; Gao T; Yang X; Dai XC; Zhou W; Zhang AQ; Lieber CM Specific detection of biomolecules in physiological solutions using graphene transistor biosensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113 (51), 14633–14638, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1625010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ono T; Kanai Y; Inoue K; Watanabe Y; Nakakita S -i.; Kawahara, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Matsumoto, K. Electrical Biosensing at Physiological Ionic Strength Using Graphene Field-Effect Transistor in Femtoliter Microdroplet. Nano Lett. 2019, 19 (6), 4004–4009, DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kovalska E; Lesongeur P; Hogan BT; Baldycheva A Multi-layer graphene as a selective detector for future lung cancer biosensing platforms. Nanoscale 2019, 11 (5), 2476–2483, DOI: 10.1039/C8NR08405J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Novoselov KS; Geim AK; Morozov SV; Jiang D; Zhang Y; Dubonos SV; Grigorieva IV; Firsov AA Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306 (5696), 666–669, DOI: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Woo SO; Teizer W Effects of electron beam induced Redox processes on the electronic transport in graphene field effect transistors. Carbon 2015, 93, 693–701, DOI: 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.05.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Choi YK; Moody IS; Sims PC; Hunt SR; Corso BL; Perez I; Weiss GA; Collins PG Single-Molecule Lysozyme Dynamics Monitored by an Electronic Circuit. Science 2012, 335 (6066), 319–324, DOI: 10.1126/science.1214824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Georgakilas V; Tiwari JN; Kemp KC; Perman JA; Bourlinos AB; Kim KS; Zboril R Noncovalent Functionalization of Graphene and Graphene Oxide for Energy Materials, Biosensing, Catalytic, and Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev 2016, 116 (9), 5464–5519, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wu G; Dai Z; Tang X; Lin Z; Lo PK; Meyyappan M; Lai KWC Graphene Field-Effect Transistors for the Sensitive and Selective Detection of Escherichia coli Using Pyrene-Tagged DNA Aptamer. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2017, 6 (19), 1700736, DOI: 10.1002/adhm.201700736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Goldsmith BR; Locascio L; Gao YN; Lerner M; Walker A; Lerner J; Kyaw J; Shue A; Afsahi S; Pan D; Nokes J; Barron F Digital Biosensing by Foundry-Fabricated Graphene Sensors. Sci Rep-Uk 2019, 9, 434, DOI: ARTN 434 10.1038/s41598-019-38700-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Andoy NM; Filipiak MS; Vetter D; Gutierrez-Sanz O; Tarasov A Graphene-Based Electronic Immunosensor with Femtomolar Detection Limit in Whole Serum. Adv Mater Technol-Us 2018, 3 (12), 1800186, DOI: ARTN 1800186 10.1002/admt.201800186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Choi Y; Moody IS; Sims PC; Hunt SR; Corso BL; Seitz DE; Blaszcazk LC; Collins PG; Weiss GA Single-Molecule Dynamics of Lysozyme Processing Distinguishes Linear and Cross-Linked Peptidoglycan Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (4), 2032–2035, DOI: 10.1021/ja211540z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lu J; Nagase S; Zhang X; Wang D; Ni M; Maeda Y; Wakahara T; Nakahodo T; Tsuchiya T; Akasaka T; Gao Z; Yu D; Ye H; Mei WN; Zhou Y Selective Interaction of Large or Charge-Transfer Aromatic Molecules with Metallic Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes: Critical Role of the Molecular Size and Orientation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (15), 5114–5118, DOI: 10.1021/ja058214+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zhao J; Lu JP; Han J; Yang C-K Noncovalent functionalization of carbon nanotubes by aromatic organic molecules. Appl. Phys. Lett 2003, 82 (21), 3746–3748, DOI: 10.1063/1.1577381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Prisbrey L; Schneider G; Minot E Modeling the Electrostatic Signature of Single Enzyme Activity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114 (9), 3330–3333, DOI: 10.1021/jp910946v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Adam S; Hwang EH; Galitski VM; Das Sarma S A self-consistent theory for graphene transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2007, 104 (47), 18392–18397, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0704772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Martin J; Akerman N; Ulbricht G; Lohmann T; Smet JH; von Klitzing K; Yacoby A Observation of electron–hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nat Phys 2008, 4 (2), 144–148, DOI: 10.1038/nphys781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Fu W; Feng L; Panaitov G; Kireev D; Mayer D; Offenhäusser A; Krause H-J Biosensing near the neutrality point of graphene. Science Advances 2017, 3 (10), e1701247, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1701247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Woo SO; Teizer W The effect of electron induced hydrogenation of graphene on its electrical transport properties. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 103 (4), 041603, DOI: Artn 041603 10.1063/1.4816475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ferrari AC; Meyer JC; Scardaci V; Casiraghi C; Lazzeri M; Mauri F; Piscanec S; Jiang D; Novoselov KS; Roth S; Geim AK Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys Rev Lett 2006, 97 (18), 187401 DOI: ARTN 187401 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.187401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Morozov SV; Novoselov KS; Katsnelson MI; Schedin F; Elias DC; Jaszczak JA; Geim AK Giant intrinsic carrier mobilities in graphene and its bilayer. Phys Rev Lett 2008, 100 (1), 016602 DOI: ARTN 016602 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.016602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Adam S; Das Sarma S Boltzmann transport and residual conductivity in bilayer graphene. Phys Rev B 2008, 77 (11), 115436 DOI: ARTN 115436 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.115436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Woo SO; Yudhistira I; Hemmatiyan S; Morrison TD; Rathnayaka KDD; Naugle DG Transport properties of bilayer graphene decorated by K adatoms in the framework of Thomas-Fermi screening. Phys Rev B 2019, 99 (8), 085416, DOI: ARTN 085416 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.085416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Koshino M Electronic transport in bilayer graphene. New J Phys 2009, 11, 095010, DOI: Artn 095010 10.1088/1367-2630/11/9/095010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).McCann E; Koshino M The electronic properties of bilayer graphene. Rep Prog Phys 2013, 76 (5), 056503, DOI: Artn 056503 10.1088/0034-4885/76/5/056503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lu HP Single-Molecule Protein Interaction Conformational Dynamics. Curr. Pharm. Biotechno 2009, 10 (5), 522–531, DOI: 10.2174/138920109788922119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Alava T; Mann JA; Theodore C; Benitez JJ; Dichtel WR; Parpia JM; Craighead HG Control of the Graphene-Protein Interface Is Required To Preserve Adsorbed Protein Function. Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (5), 2754–2759, DOI: 10.1021/ac303268z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Yang Z; Jiménez-Osés G; López CJ; Bridges MD; Houk KN; Hubbell WL Long-Range Distance Measurements in Proteins at Physiological Temperatures Using Saturation Recovery EPR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (43), 15356–15365, DOI: 10.1021/ja5083206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lerner MB; Pan D; Gao Y; Locascio LE; Lee K-Y; Nokes J; Afsahi S; Lerner JD; Walker A; Collins PG; Oegema K; Barron F; Goldsmith BR Large scale commercial fabrication of high quality graphene-based assays for biomolecule detection. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem 2017, 239, 1261–1267, DOI: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Goldsmith BR; Locascio L; Gao Y; Lerner M; Walker A; Lerner J; Kyaw J; Shue A; Afsahi S; Pan D; Nokes J; Barron F Digital Biosensing by Foundry-Fabricated Graphene Sensors. Scientific Reports 2019, 9 (1), 434, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-38700-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.