Abstract

Germline mutations of DNA double-strand break (DSB) response and repair genes that drive tumorigenesis could be a major cause of prostate cancer (PCa) heritability. In this study, we demonstrated the role of novel exonuclease 5 (EXO5) gene in androgen-induced double strand breaks repair via homology-directed repair pathway and prostate tumorigenesis. Using whole-exome sequencing of samples from 20 PCa families, with three or more siblings diagnosed with metastatic PCa, we identified mutations in 31 genes involved in DSB response and repair. Among them, the L151P mutation in the exonuclease 5 (EXO5) gene was present in all affected siblings in three PCa families. We found two other EXO5 SNPs significantly associated with risk of PCa in cases-controls study from databases of genotype and phenotype (dbGaP), which are in linkage disequilibrium (D’=1) with Exo5 L151P found in PCa family. The L151 residue is conserved across diverse species and its mutation is deleterious for protein functions, as demonstrated by our bioinformatics analyses. The L151P mutation impairs the DNA repair function of EXO5 due to loss of nuclease activity, as well as failure of nuclear localization. CRISPR elimination of EXO5 in a PCa cell line impaired homology-directed recombination repair (HDR) and caused androgen-induced genomic instability, as indicated by frequent occurrence of the oncogenic fusion transcript TMPRSS2-ERG. Genetic and functional validation of the EXO5 mutations indicated that EXO5 is a risk gene for prostate tumorigenesis, likely due to its functions in HDR.

Keywords: Androgen signaling, DNA damage response and repair, Exonuclease 5, Prostate cancer, Whole-exome sequencing

Introduction

Double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) are the most deleterious type of DNA lesion in cells (1). If they are not repaired immediately, DSBs cause large-scale genomic instability, which increases cancer susceptibility by disrupting tumor suppressor genes or generating oncogenic fusions (2–4). DSB repair is carried out by either of two dedicated pathways in cells: homology-directed repair (HDR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Several factors, including cell cycle check point and DNA repair activation genes, determine which pathway is used for repair (5). Moreover, functional deficiency in HDR genes caused by germline mutations, such as mutations in the ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) gene, promotes NHEJ for DSB repair, leading to chromosomal translocations (6). DNA end resection, which is carried out by exonucleases that generate single-stranded DNA for HDR, is a key step contributing to repair pathway choice (5,7). The nucleases MRE11, DNA2, and exonuclease 1 (EXO1) have established roles in end resection for HDR (8,9). Another nuclease, EXD2, has recently been identified as involved in the end resection process (10). Mutations in these nucleases can reduce HDR efficiency, leading cells to favor the NHEJ pathway. Because repair by NHEJ does not involve a template DNA strand, it is an error-prone process that causes mutations, translocations, and genomic instability (11).

Prostate tissue is constantly exposed to androgen-induced topoisomerase IIb (TOP2)-mediated DSBs to resolve DNA catenanes during active transcription of androgen receptor target genes (12,13). During the process, TOP2 becomes covalently bound to the 5’ DNA end of the break and forms TOP2-DNA cleavage complex intermediates (Top2cc). Given the frequency of these events in prostate cells, inefficient or failed removal of Top2cc leads to the generation of complex or blocked DSB ends with associated Top2cc lesions. The protein-linked DSB ends generated by androgen signaling in prostate epithelial cells possess additional interference for normal DSB repair (13). Although it is known that DNA ends with bulky protein adducts are channeled exclusively to end resection processes (7), the nucleases required for those processes have not been defined. However, recent studies have suggested roles for ATM and MRE11 in accurately repairing TOP2 cross-linked DSBs and preventing genomic instability (14,15).

We posit that the genomic instability resulting from disruption to DSB repair processes may contribute to prostate tumorigenesis. Indeed, in prostate cancer, chromosomal translocation events occur when androgen signaling, along with reduced HDR efficiency, induces illegitimate DSB repair in the genomic regions that encode transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and ETS family transcription factors (13). These fusion transcripts are found in > 50% of PCa patients and are associated with cancer aggressiveness and PCa-specific mortality (16).

In this study, using whole-exome sequencing of 20 PCa families, in which three or more siblings were diagnosed with metastatic PCa, we identified mutations in 31 key components of the DSB response and repair pathways that were shared among three siblings in at least one families. Among the 31 mutated genes, a leucine to proline mutation (L151P) in EXO5 gene was most frequently observed and was present in all affected siblings from three different families. EXO5 has been identified as a nuclear DNA damage repair gene that possesses an iron–sulfur (Fe4S4) cluster and 5’ and 3’ bi-directional exonuclease activity. In response to DNA damage, EXO5 localizes to the nucleus, where it forms DNA repair foci and repairs inter-strand cross-links (17). Our experimental data indicate that the L151P mutation results in loss of EXO5 nuclease activity and nuclear localization ability. CRISPR-Cas9 deletion of EXO5 in LNCaP PCa cell lines led to reduced HDR efficiency and greater frequency of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, which promote prostate tumorigenesis.

Results

Identification of a cluster of DNA DSB repair gene variations and the EXO5 L151P variant in PCa

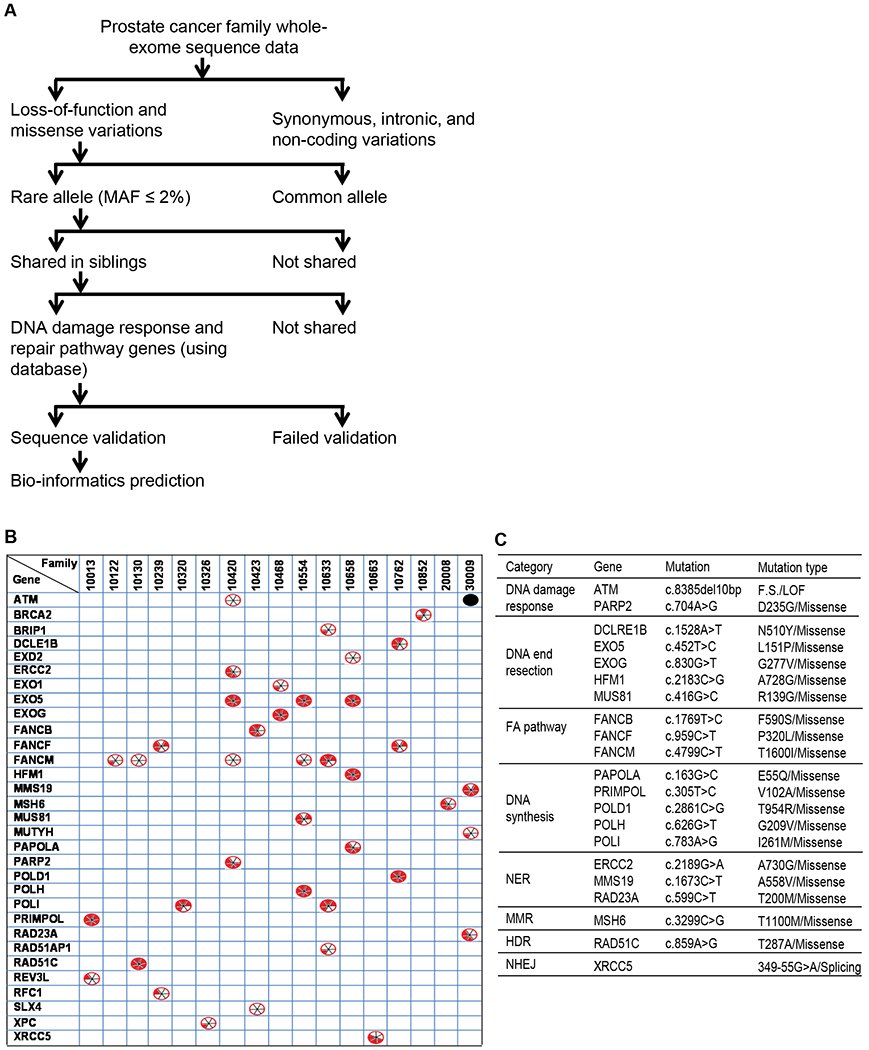

Whole-exome sequencing was performed on genomic DNA from the peripheral blood of 64 individuals with PCa, representing 20 families that had three or more brothers with PCa. All affected individuals and their families were of European ancestry. To identify deleterious genetic variations with increased penetrance of the risk allele in PCa, we developed the following approach to systematically filter mutations (Fig. 1A): 1) We selected variants that produced a high to moderate impact on gene function. High-impact variations included insertions or deletions, frame-shift changes, and splicing site variants that lead to loss of gene function. Moderate impact variations included missense mutations. 2) Among those variants, we selected those that are less frequently present in the normal population (i.e., no PCa) and that had a minor allele frequency ≤ 2%, based on 1000 Genomes Project data. 3) We selected variants that were shared by all affected siblings within at least one PCa family. 4) We then used the DAVID online bioinformatics resource (18) and DNA repair genes databases (19–21) to select DNA repair pathway genes. 5) Mutations were validated using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Table 1). 6) We predicted the pathogenicity of the mutations using six online available bioinformatics tools: Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) (22), Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2) (23), a likelihood ratio test (LRT) (24), MutationTaster (25), MutationAssessor (26), and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) (27).

Figure 1.

DNA damage response and repair gene mutations shared among members of PCa families and their predicted risk effects. (A) Flow chart showing the various criteria used to narrow down the mutations of interest and identify rare mutations likely to be pathogenic. (B) List of 31 DNA repair genes that are mutated in all PCa patients in one or more families (among 17 of the 20 PCa families studied). The black dot ( ) indicates an insertion-deletion mutation. The divided circles (

) indicates an insertion-deletion mutation. The divided circles ( ) indicate missense mutations. Red sectors indicate that the mutations were predicted to have deleterious effects on gene function according to in silico analyses using one of six programs: 1. SIFT; 2. PolyPhen-2; 3. LRT; 4. MutationTaster; 5.MutationAssessor; 6. CADD. For details see the Materials and Methods section. (C) Functional categorization of the genes mutated in PCa families into eight major groups.

) indicate missense mutations. Red sectors indicate that the mutations were predicted to have deleterious effects on gene function according to in silico analyses using one of six programs: 1. SIFT; 2. PolyPhen-2; 3. LRT; 4. MutationTaster; 5.MutationAssessor; 6. CADD. For details see the Materials and Methods section. (C) Functional categorization of the genes mutated in PCa families into eight major groups.

We thus identified 31 rare mutations in key components of the DSB response and repair pathways that were shared among three siblings at least in one of the 20 families (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 2). Among the 31 mutated DNA repair genes, we considered 21 to be potentially deleterious because they were predicted to be deleterious using three or more in silico analyses. The genes harboring potentially deleterious mutations were categorized into the following eight functional groups: DNA damage response, nucleases and helicases involved in DNA end resection, Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, DNA synthesis, nucleotide excision repair (NER), mismatch repair (MMR), HDR, and NHEJ (Fig. 1C). Among these mutations, the most frequent was a leucine to proline mutation (L151P) in the EXO5 gene, which was present in all affected siblings of three different families (Fig. 2A). All six bioinformatics tools used predicted the EXO5 L151P mutation to be deleterious (Fig. 2B). Hence, we further explored the functions of the EXO5 gene and the L151P mutation in prostate tumorigenesis.

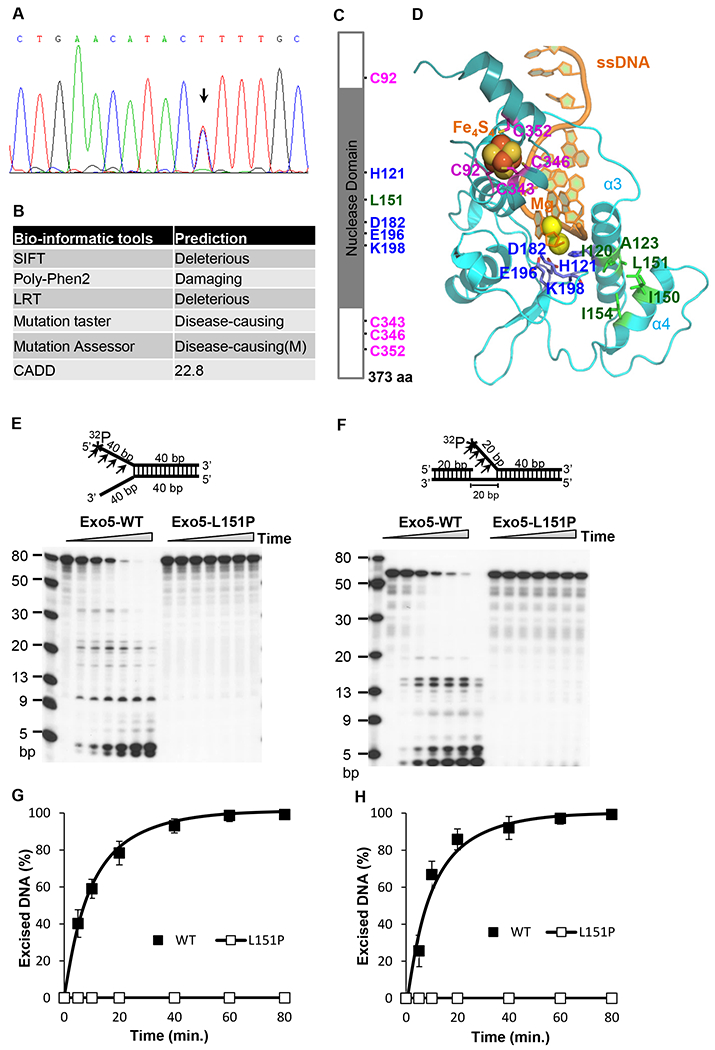

Figure 2.

Predicted structure and function of EXO5 and EXO5-L151P. (A) Validation of EXO5 L151P variation (c.452 T>C; arrow) using the Sanger sequencing method. (B) Deleterious effects of the EXO5 L151P mutation on gene function, as predicted by in silico analysis using six different bio-informatics tools. M: Moderate. A mutation with a CADD score greater 20 (top 1% of relative deleterious variants) is considered deleterious. (C) Schematic of the EXO5 protein, showing the L151P mutation in the nuclease domain. Four conserved cysteine residues (C92, C343, C363, and C352) for Fe4S4 cluster binding and four residues (H121, D182, E196, and K198) require to stabilize α-helixes 3 and 4 (α3 and α4) for the nuclease function of EXO5. (D) The EXO5 homology model. The two catalytic metal Mgs are fixed by H121, D182, E196. The Fe4S4 cluster is chelated by four cysteine residues (C92, C343, C346, C352). Hydrophobic interaction residues (I120/A123 and L151/I150/I154) stabilize the interaction between the two α-helixes (α3 and α4, respectively). (E) Nuclease activity profiles of wild-type and L151P EXO5 using a 5’ 32P-labeled (*) fork-head DNA substrate (80 bp). A reaction mixture containing 0.5 pmol of DNA substrate was incubated at 37°C for 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 min and resolved on a 7 M urea-15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands of excised DNA were visualized using autoradiography. (F) Nuclease activity profiles of wild-type and L151P EXO5 using a 5’ 32P-labeled (*) single-flap DNA substrate (60 bp). A reaction mixture containing 0.5 pmol of DNA substrate was incubated at 37°C for 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 min and resolved on a 7 M urea-15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands were visualized using autoradiography. (G) The quantification of mean excision frequency ± standard deviation of the DNA substrate in Figure 2E from three independent experiments. (H) The quantification of mean excision frequency ± standard deviation of the DNA substrate of Figure 2F from three independent experiments.

To further explore the possibility of EXO5 mutations in conferring PCa susceptibility, we analyzed data from PCa case-control studies submitted to the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP). In this study 505219 genome-wide SNPs were genotyped in a total of 2507 total samples (1591 PCa patients and 916 healthy controls). Association analysis using PLINK tools (28) showed that two out of three EXO5 SNPs studied in this population were significantly associated with risk of PCa (rs12068587: P = 2.43x10−14, odds ratio = 1.57; rs11208299: P = 4.30x10−13, odds ratio = 1.53) (Table 1). These two EXO5 SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium (D’=1) with the L151P mutation, according to our analysis of genomic data from a European population (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, a truncating somatic mutation in the EXO5 gene (I150Tfs*32) was also reported in prostate adenocarcinoma in a previous study (29,30). However, to date, the role of EXO5 in the repair of DSBs generated during hormone-induced cancer initiation is not clear.

Table 1:

EXO5 SNP frequency in a PCa case-control analysis of data from the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes.

| SNP | Chr | Base paira | Allele 1 | AF_Caseb | AF_Controlc | Allele 2 | P-valued | OR(95% CI)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3795347 | 1 | 40974156 | G | 0.2388 | 0.2407 | A | 0.8808 | 0.98(0.86-1.13) |

| rs12068587 | 1 | 40974799 | A | 0.4912 | 0.3799 | G | 2.43E-14 | 1.57(1.40-1.77) |

| rs11208299 | 1 | 40980731 | C | 0.5009 | 0.3949 | A | 4.30E-13 | 1.53(1.36-1.73) |

Human genome assembly GRCh37.p13/hg19

Allele frequency in PCa patients

Allele frequency in healthy controls

Chi-square P-value

Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval

The L151P mutation results in complete loss of the nuclease activity of EXO5

A homology-based model of the 3D structure of the EXO5 N-terminus was downloaded from the SWISS-MODEL Repository (31), and a C-terminal model (including the Fe4S4 cluster, two catalytic Mg++ atoms, and the single-stranded DNA) was built from structural alignment using mouse DNA2 (Protein Data Bank ID: 5EAN) as a template (Fig. 2C, D). The homology model of EXO5 correctly reproduced the protein structure, with four conserved cysteines (C92/C343/C346/C352) that chelate with the Fe4S4 cluster. Moreover, we were able to demonstrate that four additional residues (H121/D182/E196/K198) coordinate the two catalytic Mg++ atoms. All these residues are conserved across various species (Supplementary Fig. 2). As displayed in Figure 2D, L151 is the central residue of helix α4 (amino acids 145–157), which interacts with helix α3 (amino acids 112–131) via hydrophobic interactions between I150/L151/I154 and I120/A123. The L151 residue is also conserved across species. The α4 helix is important for protecting the catalytic metals by shielding the α3 helix, which includes the H121 chelation residue. When L151 is replaced by a proline, thus losing the bulky hydrophobic side-chain of leucine, the α3/α4 helical bundle is destabilized and separated. Thus, the substitution destabilizes the interaction between H121 and the catalytic metals, potentially resulting in loss of nuclease activity. The separation of the α3/α4 helical bundle due to the L151P mutation may also affect the translocation of EXO5 through the nuclear membrane.

We thus tested the impact of the L151P mutation of EXO5 on its nuclease activity. We expressed FLAG-tagged wild-type and L151P EXO5 in HEK293T cells and purified the proteins using anti-FLAG antibodies attached to M2-magnetic beads (Supplementary Fig. 3). We assessed the in vitro ability of the wild-type and mutant proteins to excise single-stranded DNA using a 5’ 32P-labeled 80-nucleotide fork-like double-stranded DNA substrate, similar to the substrate used in previous studies (17). As expected, the wild-type EXO5 catalyzed excision of single-stranded DNA from the labeled substrate, whereas the L151P mutation abolished this nuclease activity (Fig. 2E, G). To assess the in vitro DNA end resection activity of EXO5, we designed another DNA substrate in which the endonuclease activity of MRN creates a nick upstream of a double-stranded DNA break and a helicase displaces the DNA so that it is accessible to exonucleases. This step is necessary and required for long-distance DNA end resection during HDR. Using this substrate, similar to previous results, we found that wild-type EXO5 could catalyze cleavage of single-stranded DNA from the substrate, whereas the L151P mutant lacked such activity (Fig. 2F, H).

The L151P mutation impairs EXO5 nuclear localization

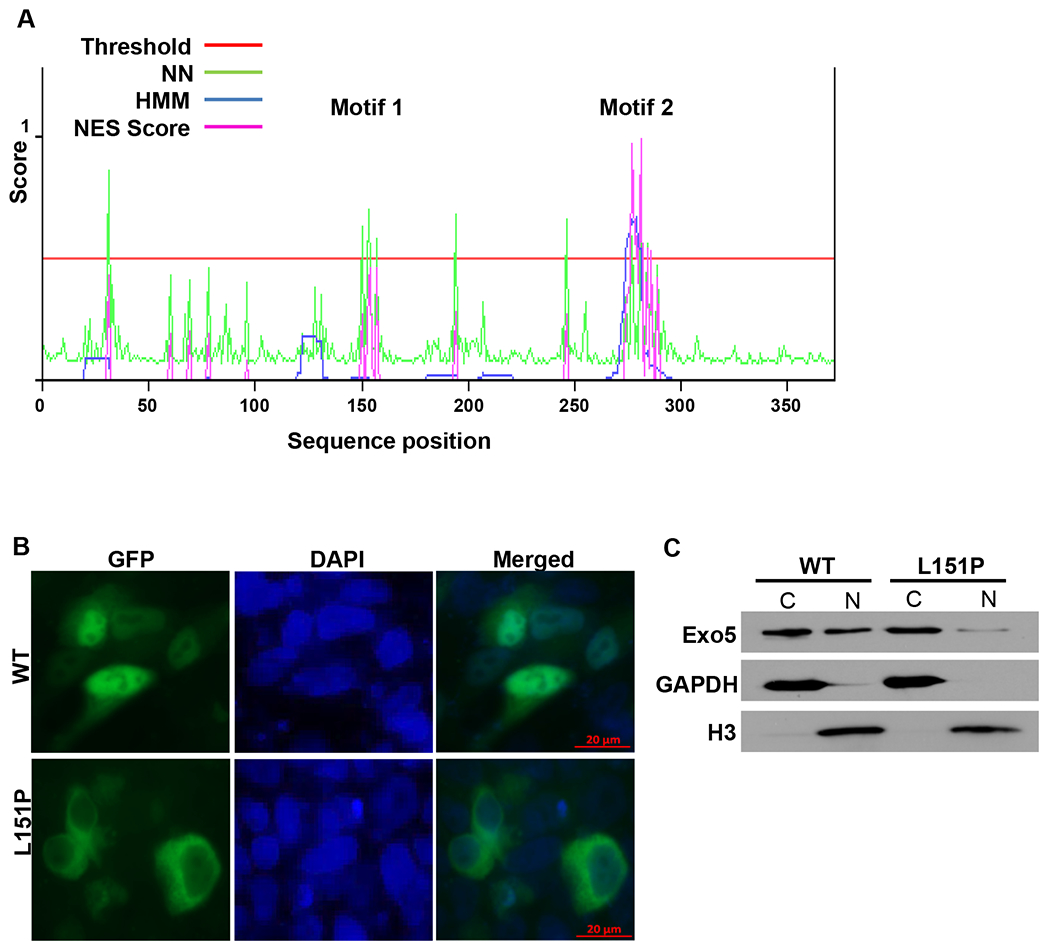

The localization of EXO5 to DNA repair foci in the nucleus is an essential step during DNA damage repair (17). Here, we tested if the EXO5 L151P mutation affects its nuclear localization and DNA repair functions. Using the online NetNES 1.1 Server tool, the full-length amino acid sequence of EXO5, and an artificial neural network (ANN) value cut-off of 0.5, we searched for nuclear localization or export signals (NLS/NES) in EXO5 (Fig. 3A) (32). This analysis identified two motifs as leucine-rich NESs: the sequence ILLLIPTLQ (amino acids 150–158) and the sequence LSLTLSDLPVIDI (amino acids 277–290). The NES exports the protein out of the nucleus; however, wild-type EXO5 localizes to the nucleus for its function, indicating that the NES in EXO5 is inactive or hidden inside the protein structure.

Figure 3.

The EXO5 L151P mutation disrupts the NES and localization of EXO5 to the nucleus. (A) NES scores for the full-length amino acid sequence of EXO5, as determined using the NetNES 1.1 Server tool. The tool uses neural networks (NN) and hidden Markov models (HMM) in a prediction algorithm. A threshold value of 0.5 was selected for NES prediction. Predicted NES motifs were ILLLIPTLQ (Motif 1, amino acids 150–158) and LSLTLSDLPVIDI (Motif 2, amino acids 277–289). (B) Immunofluorescence images of LNCaP cells transiently transfected with GFP-fused wild-type (WT) and L151P EXO5. Cells were counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei. (C) Western blot analysis of GFP-fused wild-type (WT) and L151P EXO5 expression using anti-GFP antibodies in cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions of LNCaP cells transiently transfected as described in Figure 3B. GAPDH and Histone H3 are shown as loading controls for the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

To test if the L151P mutation affects the NES and the localization of EXO5 to the nucleus, we generated plasmids containing wild-type or mutant EXO5 gene cloned downstream of the GFP gene. We then transfected LNCaP cells with these plasmids, and examined the localization of wild-type and L151P GFP-EXO5. Consistent with a previous study (17), we found that the EXO5 protein localized mostly to the nucleus but was also present in the cytosol. However, the L151P substitution abrogated its localization to the nucleus, as indicated by the presence of GFP fluorescence only in the cytosol (Fig. 3B). The mutation likely exposes the NES, which exports the protein out of the nucleus. These results were confirmed by Western blot analyses of purified cytosolic and nuclear fractions from the transfected LNCaP cells, using anti-GFP antibodies to detect GFP-fused EXO5 (Fig. 3C). The results of the Western blot analyses indicate that more than 98% of the protein was exported to the cytosol.

Loss of EXO5 gene impairs androgen-induced DSB repair and induces genomic instability

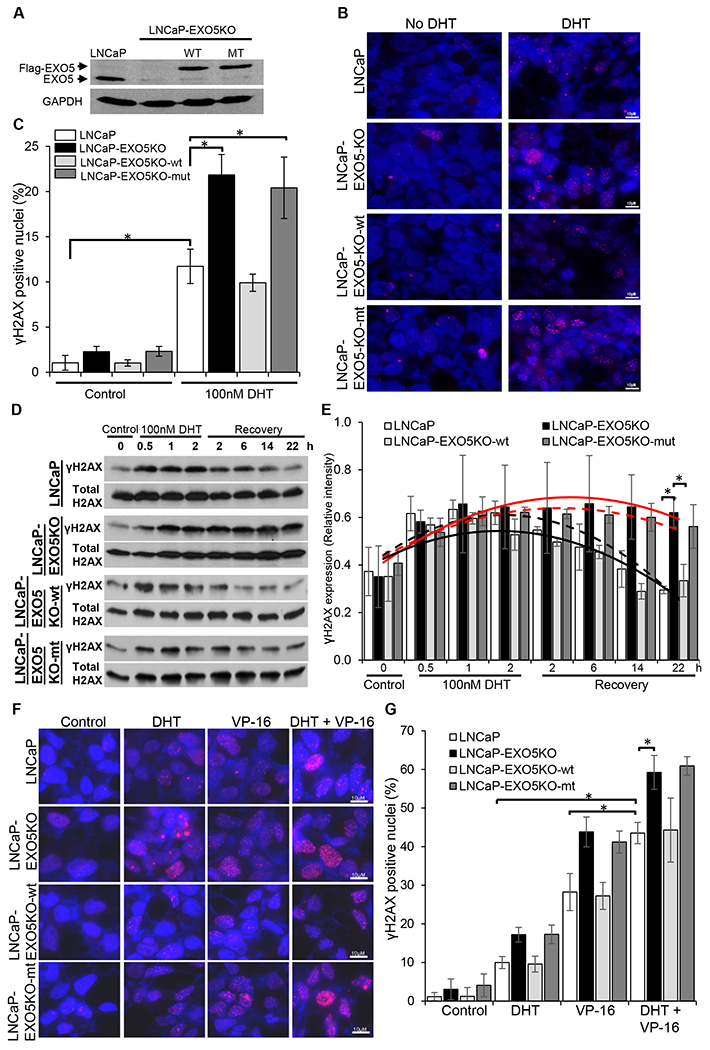

Androgen receptor signaling promotes DSBs in androgen-sensitive PCa cell lines (12,13). We tested whether loss of EXO5 function in the androgen-sensitive LNCaP cell line contributes to androgen-induced DSBs and genomic instability. To do this, we generated an EXO5 knockout LNCaP cell line using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Supplementary Table 2) (33). Disruption of the EXO5 coding region was confirmed by sequencing the target region (Supplementary Fig. 4) and assessing protein expression (Fig. 4A). We tested the sensitivity of both the parental and nuclease-defective LNCaP cells to treatment with the androgen hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which increases the expression of prostate specific antigen (PSA) (Supplementary Fig. 5). We found that DHT (100 nM, 2 h) promotes DSBs in LNCaP cells, as detected using γH2AX foci as a read-out for the DNA damage response. There were significantly more γH2AX-positive nuclei among nuclease-defective LNCaP cells than among parental LNCaP cells after DHT treatment (Fig. 4B, C). We then explored the effect of the EXO5 mutation on DNA damage repair by overexpressing the wild-type and mutant EXO5 protein in the EXO5 knockout cell line (Fig. 4A). EXO5 knockout cells that overexpressed wild-type EXO5 had similar numbers of γH2AX-positive nuclei compared to parental LNCaP cells after DHT treatment, suggesting similar amounts of DNA damage in the two lines. However, EXO5 knockout cells that overexpressed L151P mutant EXO5 were not rescued from DNA damage and had greater numbers of γH2AX-positive nuclei compared to the parental LNCaP cells after DHT treatment (Fig. 4B, C). Further, time-course assays for γH2AX levels in an immunoblotting (Fig. 4D, E) and foci numbers in immunofluorescence experiments (Supplementary Fig. 6), showed increase of γH2AX in the parental LNCaP cells after DHT treatment (2h) and gradually decreased over 24 h of recovery. In contrast, levels of γH2AX remained high in EXO5 knockout cells, even after 24 h of recovery. Overexpression of only wild-type EXO5, not L151P EXO5, in LNCaP-EXO5KO cells gradually decreases γH2AX levels after DHT treatment over 24 h of recovery. These results suggest that EXO5 is involved in the DNA damage response to androgen-induced DSBs in PCa cells and specifically, that the loss of EXO5 function leads to accumulation of DNA damage due to unrepaired DSBs and contributes to genomic instability.

Figure 4.

Knockout of EXO5 promotes DHT-induced DNA damage in androgen-sensitive PCa cells. (A) Western blot analysis of endogenous EXO5 and overexpressed FLAG-tagged wild-type (WT) and mutant (MT) EXO5 in an LNCaP EXO5 knockout (KO) cell line. (B) Immunofluorescence images of DHT-treated (100 nM, 2 h) parental LNCaP and LNCaP-EXO5KO cells, overexpressing WT or MT EXO5, stained for γH2AX. (C) The quantification of γH2AX-positive nuclei (5 or more foci present in the nucleus) per field in cells transfected and treated as described in Figure 4B. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation of three fields per experiments from 3 independent experiments. *P< 0.05. (D) Time-course assay of γH2AX expression using western blot analysis of cell lysate from LNCaP and LNCaP-EXO5-KO cells, overexpressing WT or MT EXO5, untreated and after DHT treatment (100 nM, 2 h) or recovery (incubation in media without DHT) for the indicated times. (E) The quantification of mean band intensity ± standard deviation, indicating phospho-γH2AX expression, in three independent experiments, as represented in Figure 4D. *P < 0.05. Black solid line: LNCaP cells, Red solid line: LNCaP-EXO5KO cells. Black dash line: LNCaP-EXO5KO-wt cells, Red dash line: LNCaP-EXO5KO-mut cells. (F) Immunofluorescence images of parental LNCaP, EXO5-KO, and WT EXO5-overexpressing EXO5-KO cells after treatment with DHT (100 nM, 2 h) and/or the TOP2 inhibitor VP-16 (10μM, 30 min), stained for γH2AX. (G) The quantification of γH2AX-positive nuclei (10 or more foci present in nucleus) per field in LNCaP, EXO5-KO, and WT EXO5-overexpressing EXO5-KO cells treated as described in Figure 4F. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation of three fields per experiments from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Under androgen stress, inhibition of TOP2, an enzyme that catalyzes transient DSB formation to resolve topological DNA constraints, can produce prolonged DSBs (12). We explored the role of EXO5 in inducing DNA damage upon combined treatment with the androgen hormone DHT and the TOP2 inhibitor VP-16. The combined treatment of LNCaP parental cells with DHT (100 nM, 2 h) and VP-16 (10μM, 30 min) induced DNA damage that was significantly greater than that observed upon treatment with DHT or VP-16 alone (Fig. 4F, G). EXO5 knockout LNCaP cells treated with DHT and VP-16 had significantly more γH2AX-positive nuclei, as compared to parental LNCaP cells that received the same treatment (Fig. 4F, G). Overexpression of wild-type EXO5 in nuclease-deficient cells reduced DNA damage after treatment with DHT and/or VP-16 to levels similar to those of parental cells after the same treatments. To further confirm the role of EXO5 in DHT and/or VP-16 induced DNA damage repair, we used another androgen sensitive cell line, LAPC4, and generated EXO5 knockout using CRISPR-Cas9 technique (Supplementary Fig. 7A). We observed similar results that LAPC4-EXO5KO cells treated with DHT and/or VP-16 had significantly more γH2AX-positive nuclei, as compared to parental LAPC4 cells that received the same treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7B, C). These results showed that androgen signaling promotes TOP2-mediated DSBs and that loss of EXO5 function significantly reduces the cellular capacity to repair bulky protein-bound DSBs.

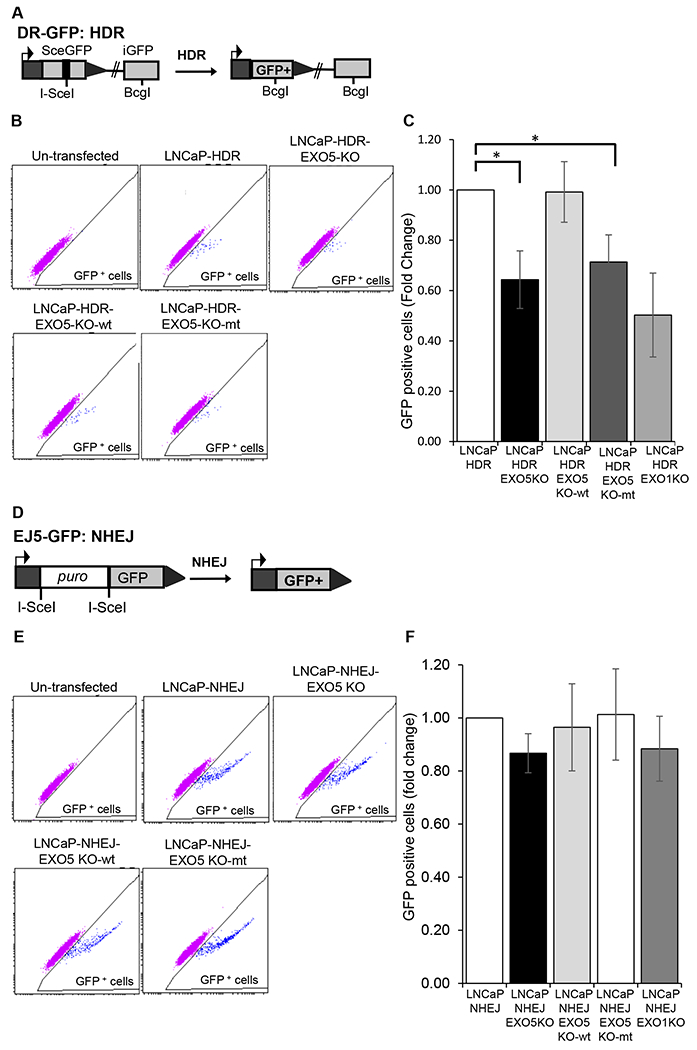

EXO5 plays an important role in HDR

We explored the role of EXO5 in HDR by using cellular I-SceI/GFP reporter-based HDR (DR-GFP) and NHEJ (EJ5-GFP) assays (34). The DR-GFP and EJ5-GFP reporters were stably integrated into LNCaP cells as described previously (6). The DR-GFP reporter comprises an open reading frame of GFP that is disrupted by an I-SceI restriction site (SceGFP) and a downstream homology template (iGFP). The I-SceI endonuclease induces DSBs in the upstream SceGFP cassette, which is followed by HDR that uses the downstream iGFP to prime nascent DNA synthesis and restore the GFP cassette (Fig. 5A). The EJ5-GFP reporter comprises an open reading frame of GFP that is disrupted by a puromycin resistance gene (Fig. 5D). The puromycin resistance gene is flanked by two I-SceI restriction sites. I-SceI endonuclease digestion leads to removal of the puromycin resistance gene, and the two ends of the GFP gene are joined through NHEJ. We also knocked out the EXO5 and EXO1 genes using the CRISPR-Cas9 system in the stable LNCaP-HDR and LNCaP-NHEJ cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 4 and 8). Using these reporter assays, we observed that knockout of the EXO5 gene in LNCaP-HDR cells significantly reduced their HDR efficiency compared to that of the parental cell line, as indicated by fewer GFP-positive cells according to flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 5B, C and Supplementary Fig. 9A). Reduction of HDR efficiency in LNCaP-HDR-EXO5KO cells was rescued by overexpressing wildtype EXO5 but not the mutant EXO5. We saw similar results in EXO1 knockout cells (Supplementary Fig. 9A), which is consistent with previous results showing that EXO1 knockout reduces HDR efficiency (35,36). However, knockout of the EXO5 gene in the LNCaP-NHEJ cell line, similar to knockout of EXO1 (37), did not significantly change NHEJ repair efficiency compared to that of the parental LNCaP-NHEJ cell line (Fig. 5E, F, and Supplementary Fig. 9B). Reduction in HDR efficiency of EXO5-deficient LNCaP-HDR cells was rescued by overexpressing wildtype EXO5 but not the mutant EXO5.

Figure 5.

EXO5 is required for HDR of DSBs. (A) I-SceI-based GFP reporter cassette for the DR-GFP HDR assay. (B) Representative flow cytometry profile of untransfected and I-SceI-transfected LNCaP cells containing HDR GFP reporter cassettes (LNCaP-HDR). Cells showing green fluorescence greater than autofluorescence were gated to determine the percentage of GFP+ cells. Knockout of the EXO5 gene in LNCaP-HDR cells (LNCaP-HDR-EXO5KO) significantly reduced HDR efficiency, and overexpression of wild-type (WT) EXO5 restored HDR efficiency. (C) The quantification of mean ± standard deviation of GFP+ cells in at least three independent transfections, as represented in Figure 5B. *P < 0.05. (D) I-SceI-based GFP reporter cassette for the EJ5-GFP NHEJ repair assay. (E) Representative flow cytometry profile of untransfected and I-SceI-transfected cells containing NHEJ GFP reporter cassettes (LNCaP-NHEJ). Cells showing green fluorescence greater than autofluorescence were gated to determine the percentage of GFP+ cells. Knockout of the EXO5 gene in LNCaP-NHEJ cells (LNCaP-HDR-EXO5KO) did not reduce NHEJ repair efficiency. (F) The quantification of mean ± standard deviation of GFP+ cells in at least three independent transfections, as represented in Figure 5E. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests. *P < 0.05.

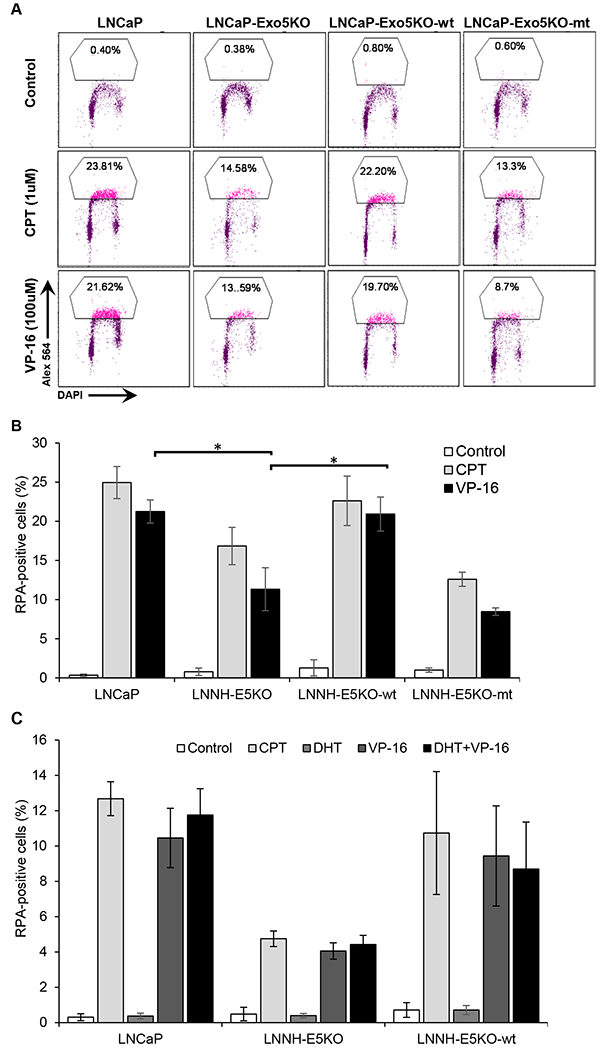

Loss of EXO5 function reduces DNA end resection for HDR

DNA end resection, which is a key step for the choice between HDR and NHEJ repair pathways, generates single-stranded DNA for strand invasion and homology-mediated DSB repair (5,7). In order to study the role of EXO5 in end resection, we performed a flow cytometry-based assay, involving the detection of chromatin-bound single-stranded DNA binding protein RPA (38). EXO5-deficient LNCaP cells treated with the topoisomerase I inhibitor Camptothecin (CPT, 1 μM, 1 h) and TOP2 inhibitor VP-16 (100 μM, 1 h) exhibited significantly less chromatin-bound RPA than similarly treated LNCaP parental cells (Fig. 6 A, B). Reduction of chromatin-bound RPA in EXO5-deficient LNCaP cells was rescued by overexpressing wildtype EXO5. Further, we explored the role of EXO5 in DNA end resection upon combined treatment with DHT and VP-16. The combined treatment of LNCaP parental cells resulted in slightly increase in chromatin-bound RPA level than treatment with VP-16 alone (Fig. 6C). EXO5 knockout LNCaP cells treated with DHT and/or VP-16 had significantly less chromatin-bound RPA compared to parental LNCaP cells that received the same treatments. Reduction of chromatin-bound RPA in EXO5-deficient LNCaP cells was rescued by overexpressing wildtype EXO5. These results showed that EXO5 is involved in DNA end resection necessary for the repair of androgen-induced TOP2-mediated DSBs and that the loss of EXO5 function likely impairs the HDR pathway.

Figure 6.

Knockout of the EXO5 gene and treatment with the TOP2 inhibitor VP-16 causes a reduction in end resection, as detected by damage-induced chromatin-bound RPA. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots and the percentage of LNCaP parental, EXO5 knockout (KO), and wild-type (WT) EXO5-overexpressing EXO5 KO cells showing chromatin-bound phosphor-RPA staining left untreated or after treatment with topoisomerase I inhibitor CPT (1 μM) or VP-16 (100 μM) for 1 h. (B) The quantification of the mean percentages of cells ± standard deviation showing chromatin-bound phosphor-RPA staining in three independent treatment experiments, as represented in Figure 6A. *P < 0.05. (C) Cells were androgen deprived for 48 h and treated with DHT (100 μM, 2 h) followed by treatment with/without VP-16 (100 μM, 1 h). Shown are the mean percentages ± standard deviation of cells showing chromatin-bound phosphor-RPA staining in at least three independent treatment experiments. *P < 0.05.

Loss of the EXO5 gene promotes TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion frequency

A previous study showed that androgen signaling also promotes non-random translocation events between TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor family genes in PCa (13). Indeed, the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion is the most common gene rearrangement that occurs in PCa (39). Therefore, we assessed the role of the EXO5 gene in DHT-induced de novo TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in EXO5-deficient LNCaP cells (Fig. 7A). To detect fusion transcripts, we used a previously developed, highly sensitive RT-PCR assay using primers specific to exon 1 of TMPRSS2 and exon 6 of ERG. VCaP cells, which have a single copy of the genomic TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, were used as a positive control in this assay. DHT stimulation (100 nM, 24 h) of parental LNCaP cells led to an approximately 3-fold increase in the level of the gene fusion product, as detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 7B, C). However, combined treatment of cells with mild dose of IR (1Gy) and DHT does not show difference in gene fusion frequency compared to DHT treatment alone. Although LNCaP cells do not typically exhibit the gene fusion events, a low background level of the fusion product was observed because the cell lines were maintained in fully supplemented, androgen-containing media. This was consistent with similar phenomena that were observed in a previous study (12). DHT treatment of EXO5 knockout cells led to a greater increase in gene fusion levels, approximately 4.5-fold that observed in untreated parental LNCaP cells. The fusion product was verified by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 10). Because previous work has shown that the combined inhibition of the EXO1 gene and DHT treatment increases the frequency of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion events (13), we used EXO1 knockout LNCaP cells as positive controls in this experiment. We also assessed the effects of the EXO5 L151P mutation on gene translocation by overexpressing wild-type and L151P mutant EXO5 proteins in EXO5 knockout cells. EXO5 knockout cells that overexpressed wild-type EXO5 showed a similar gene fusion frequency as parental cells after DHT treatment, indicating that wild-type EXO5 rescued the cells from increased gene rearrangement events. However, overexpression of the L151P EXO5 did not rescue the cells, which instead showed gene fusion frequencies that were similar to those of the EXO5 knockout cells (Fig. 7D, E). Further, we also observed that knockout of EXO5 in PCa LNCaP cells increases cell proliferation rate and cellular migration (Supplementary Fig. 11). However, overexpression of wildtype Exo5 in Exo5-deficient cells rescue these phenotype.

Figure 7.

Knockout of the EXO5 gene enhances the frequency of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in LNCaP cells after DHT treatment. (A) Schematic of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion transcripts. Fusion involving exon 1 of TMPRSS2 and exon 4 of ERG is shown. (B) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR amplification of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcript in VCaP cells (fusion transcript-positive control) and IR- and/or DHT-treated LNCaP cells. RT-PCR used primers specific to exon 1 of TMPRSS2 and exon 6 of ERG. Knockout of EXO1 or EXO5 genes in LNCaP cells significantly enhanced gene fusion frequency. (C) The quantification of mean band intensity ± standard deviation of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcript in three independent experiments, as represented in Figure 7B. * P <0.05. (D) LNCaP-EXO5KO cells were transfected with vectors to overexpress wild-type EXO5 (FLAG-EXO5-wt) and L151P mutant EXO5 (flag-EXO5-mut). Gene fusion transcripts were quantified using semi-quantitative RT-PCR, as described in Figure 7B. (E) The quantification of band intensity of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcript for the experiment shown in Figure 7D

Discussion

The heritable risk of PCa has been estimated at up to 60%, suggesting a major contribution from genetic risk factors, although the genetic basis underlying this risk remains poorly understood (29,40–43). Identifying the highly penetrant genetic factors that influence PCa risk could provide information to build regimens for cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment. Recent GWAS have implicated ~100 loci as potentially contributing to PCa risk (44–50). The germline mutations of DNA repair genes, specifically those in DNA DSB repair pathway that drive prostate tumorigenesis, have been reported to be a major cause of PCa heritability (41,51). Family-based studies are also powerful approaches that may help to identify PCa susceptibility genes, under assumption that the shared PCa phenotype will be associated with a shared genotype. However, to date, few studies have been conducted using gene sequencing of families with high prevalence of particular types of cancer due to the limited source of genetic materials from the families (42,43,52).

In the current study, we used genetic data from 20 families with three or more brothers bearing metastatic PCa to identify genes that may play a role in familial susceptibility to PCa. We identified 31 rare mutations that were shared among PCa-affected individuals in one or more families. Among the 31 mutated germline genes, six (ATM, BRCA2, BRIP1, MSH6, MUTYH, and RAD51C) had been previously identified in PCa patients through case-control studies (41) and/or familial PCa samples (51). Many of the genes identified fall into functional categories related to the DSB response and repair pathways, including DNA end resection nucleases, FA pathway components, and translesion polymerases. Deficiencies in these gene functions could confer increased sensitivity to androgen hormone- and topoisomerase-mediated DSBs in prostate cells, contributing to a predisposition to PCa. However, further studies are required to validate the functions of each of these mutations.

The L151P EXO5 mutation was the most frequently observed mutation and was shared by all affected siblings in three PCa families. Interestingly, the leucine residue is conserved among EXO5 orthologs from several species, and its proline substitution was predicted by all six bioinformatics tools to be potentially deleterious to EXO5 function. The minor allele frequency of the EXO5 L151P mutation is less than 2% in the global population (based on 1000 Genomes Project data), however, in European populations, it increases to 6%, indicating increased risk. Because the L151P mutation is the less frequently occurring variant and was excluded from existing PCa case-control GWAS datasets, we could not compare its frequency in PCa patients vs. controls. Nevertheless, an association analysis on a set of GWAS data showed that other SNPs in the EXO5 gene, which are in linkage disequilibrium with the L151P mutation, are significantly associated with PCa risk. Multiple somatic mutations in EXO5 have also been previously reported in PCa and other cancers (29,30). Although these collective lines of evidence indicate that EXO5 mutations might contribute to PCa risk, the role of EXO5 and its variants in cancer have not been investigated.

EXO5 L151P mutation likely provides steric hindrance in proper protein conformation and may expose the NES or completely misfolded protein structure. Our findings established that EXO5 L151P mutation abolishes its nuclease activity and impairs its localization to the nucleus. Because both of these functions are essential for repairing damaged DNA, we proposed that loss of either may contribute to genomic instability. In our study, all affected individuals in the PCa families with the L151P EXO5 mutation were heterozygous for the mutation. Somatic loss of one wild-type allele is a frequent genetic event, also known as loss of heterozygosity that may contribute to cancer development. Indeed, loss of heterozygosity and haploinsufficiency often occur in many inherited cancer syndromes (53–55).

In cancers such as PCa, as well as ovarian and breast cancers, disregulated hormone signaling could act as a risk factor that contributes to cancer development. For example, in PCa, androgen hormone (DHT) signaling can induce DSBs, possibly due to an increased rate of collision between the androgen receptor, bound to its target gene, and the replication fork. In addition, recruitment of the DNA-cleaving complex including TOP2 and the AID/LINE-1 repeat-encoded ORF2 endonuclease by the androgen receptors to target genes results in DSB formation (12,13). Androgen response elements (AREs) are present in the promoter and enhancer regions of androgen receptor target genes, and similar AREs are present throughout the genome; therefore, androgen receptor signaling may also contribute to DSB formation throughout the genome (56). We found that loss of the EXO5 gene in PCa cells leads to increased accumulation of DNA damage after DHT treatment, which is likely due to the accumulation of unrepaired DSBs. Combined treatment of both parental LNCaP and LAPC4 cells with DHT and the TOP2 inhibitor VP-16 showed that androgen signaling promotes TOP2-mediated DSBs and that loss of EXO5 significantly enhances DNA damage. These results are consistent with a previous study (17) that showed greater genomic instability in EXO5-depleted cells compared to control cells upon treatment with inter-strand cross-link-inducing agents.

Using an in vitro biochemical assay and cellular end resection and GFP-based reporter assay, we elucidated the possible role of EXO5 in endonucleolytic end resection required for HDR. Furthermore, perhaps due to loss of HDR in EXO5 knockout LNCaP cells, we also observed an increase in gene rearrangements between TMPRSS2 and ERG loci in response to DHT treatment. These gene rearrangement events gave rise to an oncogenic fusion transcript (TMPRSS2-ERG) that is found in PCa patients and has been associated with cancer aggressiveness and PCa-specific mortality (16). Further, increase in cell proliferation rate and cellular migration observed in Exo5 knockout LNCaP cells are likely due to oncogenic fusion transcript like TMPRSS2-ERG, which is consistent to previous studies (57). We posit that the PCa tissues in patients carrying mutated EXO5 likely exhibit increased frequencies of these types of gene fusions. However, we could not estimate their frequency in our study due to a lack of PCa tissue availability. Based on our data, as well as the current literature (5,10,17), we hypothesized that EXO5 functions as an end resection nuclease that is particularly suitable for resolving the cross-linked DSBs that are induced by androgens in prostate cells. In androgen-induced DSBs, the DNA ends remain ligated within a cross-linked complex that hinders the normal end resection machinery. Therefore, at the start of end resection for DSBs with blocked ends, an incision endonuclease (MRE11) creates a nick upstream of the DSB. The DNA strands on both sides of the DSB are then displaced by 5’ and 3’ helicases and are bidirectionally excised by 5’-3’ EXO5 exonuclease and 3’-5’ EXD2 exonuclease to generate long resected ends (10). This model is supported by the results of our in vitro biochemical assay, which demonstrate that EXO5 is able to catalyze the excision of single-stranded DNA in a structure similar to that generated during end resection. The generation of long resected ends by nucleases is essential for HDR, and defects in this process likely lead to the breaks that are repaired through NHEJ, which increases genomic rearrangements and instability. Collectively, our study showed that EXO5 is likely involved in end resection and that loss of EXO5 function reduces the efficiency of HDR and increases genomic instability and the frequency of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in PCa cells.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods section is only included in the on line Supplementary Materials and Methods due to the space limit (Supplementary Materials and Methods; Supplementary Table 3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Dr. Theodore Krontiris and Dr. Ching Ouyang in City of Hope for providing the genomic DNA samples of prostate cancer families. We thank Charles Warden and Dr. Xiwei Wu for their help in genomic data deposition. Drs. Keely Walker and Kerin K. Higa for proofreading the manuscript. Research reported in this publication included work performed in the Computational Therapeutics and Integrative Genomics core facilities, which are supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA033572. The work was partially supported by City of Hope institutional Excellence Award to B.H.S.

Footnotes

Public data deposition

Genomic sequencing data are deposited to dbGaP database.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available at Oncogene Journal’s website

References

- 1.Ciccia A, and Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Molecular Cell. 2010;40:179–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, and Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, and Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussenzweig A and Nussenzweig MC (2010) Origin of chromosomal translocations in lymphoid cancer. Cell. 2010;141:27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cejka P DNA End Resection: Nucleases Team Up with the Right Partners to Initiate Homologous Recombination. J. Biol. Chem 2015;290:22931–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, and Stark JM. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genetics. 2008;4:e1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao S, Tammaro M, and Yan H. The structure of ends determines the pathway choice and Mre11 nuclease dependency of DNA double-strand break repair. Nucl. Acid. Res 2016;44:5689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, and Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia V, Phelps SE, Gray S, and Neale MJ. Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1. Nature, 2011;479:241–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broderick R, Nieminuszczy J, Baddock HT, Deshpande R, Gileadi O, Paull TT. et al. (2016) EXD2 promotes homologous recombination by facilitating DNA end resection. Nat. Cell Biol 2016;18: 271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sishc BJ, and Davis AJ. The Role of the Core Non-Homologous End Joining Factors in Carcinogenesis and Cancer. Cancers, 2017;9:81–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffner MC, Aryee MJ, Toubaji A, Esopi DM, Albadine R, Gurel B, et al. Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nat. Genet 2010;42:668–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin C, Yang L, Tanasa B, Hutt K, Ju BG, Ohgi K, et al. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell. 2009;139:1069–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez-Quilon A, Serrano-Benitez A, Lieberman JA, Quintero C, Sanchez-Gutierrez D, Escudero LM, et al. (2014) ATM specifically mediates repair of double-strand breaks with blocked DNA ends. Nat. Commun 2014;5:3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoa NN, Shimizu T, Zhou ZW, Wang ZQ, Deshpande RA, Paull TT, et al. Mre11 Is Essential for the Removal of Lethal Topoisomerase 2 Covalent Cleavage Complexes. Mol. Cell, 2016;64:580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann M. Expression of variant TMPRSS2/ERG fusion messenger RNAs is associated with aggressive prostate cancer. Can. Res 2006;66:8347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparks JL, Kumar R, Singh M, Wold MS, Pandita TK, Burgers PM. Human exonuclease 5 is a novel sliding exonuclease required for genome stability. J. Biol. Chem 2012;287:42773–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Prot 2009;4:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood RD, Mitchell M, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes. Mut. Res 2005;577, 275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milanowska K, Krwawicz J, Papaj G, Kosinski J, Poleszak K, Lesiak J, et al. (2011) REPAIRtoire--a database of DNA repair pathways. Nucl. Acid. Res 2011;39:D788–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andres-Leon E, Cases I, Arcas A, Rojas AM. DDRprot: a database of DNA damage response-related proteins. Database : the journal of biological databases and curation, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucl. Acid. Res 2003;31:3812–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Meth. 2010;7:248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res, 2009;19:1553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Meth. 2010;7:575–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucl. Acid. Res 2011;39:e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet 2014;46:310–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. AJHG. 2007;81:559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancer Genome Atlas Research. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discovery, 2012;2:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bienert S, Waterhouse A, de Beer TA, Tauriello G, Studer G, Bordoli L, et al. The SWISS-MODEL Repository-new features and functionality. Nucl. Acid Res 2017;45:D313–D319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.la Cour T, Kiemer L, Molgaard A, Gupta R, Skriver K, Brunak S. Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Protein Engineering, Design & Selection : PEDS, 2004;17:527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Prot 2013;8:2281–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunn A, Stark JM. I-SceI-based assays to examine distinct repair outcomes of mammalian chromosomal double strand breaks. Methods Mol Biol, 2012;920:379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CC, Avdievich E, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wei K, Lee K, et al. EXO1 suppresses double-strand break induced homologous recombination between diverged sequences in mammalian cells. DNA Repair. 2017;57:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature, 2008;455:770–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard SM, Yanez DA, Stark JM. DNA damage response factors from diverse pathways, including DNA crosslink repair, mediate alternative end joining. PLoS Genetics. 2015;11, e1004943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forment JV, Walker RV, Jackson SP. A high-throughput, flow cytometry-based method to quantify DNA-end resection in mammalian cells. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology, 2012;81:922–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science, 2005;310:644–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter BS, Beaty TH, Steinberg GD, Childs B, Walsh PC. Mendelian inheritance of familial prostate cancer. PNAS. 1992;89:3367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanford JL, Ostrander EA. Familial prostate cancer. Epidemiologic Reviews, 2001;23:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinberg GD, Carter BS, Beaty TH, Childs B, Walsh PC. Family history and the risk of prostate cancer. The Prostate, 1990;17:337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Berndt SI, Conti DV, Schumacher F, Han Y, et al. A meta-analysis of 87,040 individuals identifies 23 new susceptibility loci for prostate cancer. Nat. Genet 2014;46:1103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amin Al Olama A, Kote-Jarai Z, Schumacher FR, Wiklund F, Berndt SI, Benlloch S, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies to identify prostate cancer susceptibility loci associated with aggressive and non-aggressive disease. Hum. Mol. Genet 2013;22:408–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Masson G, Agnarsson BA, Benediktsdottir KR, et al. A study based on whole-genome sequencing yields a rare variant at 8q24 associated with prostate cancer. Nat. Genet 2012;44:1326–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Siddiq A, Jacobs KB, Wang Z, Lindstrom S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Hum. Mol. Genet 2011;20:3867–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeager M, Chatterjee N, Ciampa J, Jacobs KB, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Hayes RB, et al. (2009) Identification of a new prostate cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nat. Genet 2009;41:1055–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Olama AA, Guy M, Jugurnauth SK, et al. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet 2008;40:316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng SL, Liu W, Wiklund F, Dimitrov L, Balter K, Sun J, et al. A comprehensive association study for genes in inflammation pathway provides support for their roles in prostate cancer risk in the CAPS study. The Prostate. 2006;66:1556–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, Dadaev T, Tymrakiewicz M, Goh C, Jugurnauth-Little S, et al. Frequent germline deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes in familial prostate cancer cases are associated with advanced disease. Brit. J. Can 2014;110:1663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, Czene K, Havelick DJ, Scheike T, et al. Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. JAMA. 2016;315:68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merajver SD, Frank TS, Xu J, Pham TM, Calzone KA, Bennett-Baker P, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations and loss of the wild-type allele in tumors from families with early onset breast and ovarian cancer. Clin. Can. Res 1995;1:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cavenee WK, Dryja TP, Phillips RA, Benedict WF, Godbout R, Gallie BL, et al. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma. Nature, 1983;305:779–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santarosa M, Ashworth A. (2004) Haploinsufficiency for tumour suppressor genes: when you don’t need to go all the way. BBA. 2004;1654:105–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson S, Qi J, Filipp FV. Refinement of the androgen response element based on ChIP-Seq in androgen-insensitive and androgen-responsive prostate cancer cell lines. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:32611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.St John J, Powell K, Conley-Lacomb MK, Chinni SR. (2012) TMPRSS2-ERG Fusion Gene Expression in Prostate Tumor Cells and Its Clinical and Biological Significance in Prostate Cancer Progression. Journal of Cancer Science &Therapy, 2012;4:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.