Summary:

Ketogenic diets (KDs) are becoming increasingly popular with for the treatment of diabetes, yet they are associated with increased frequency of hypoglycemia. Here we report that mice fed a KD display blunted glucagon release to hypoglycemia and neuroglucopenia, suggesting that consuming a KD may increase the risk for iatrogenic hypoglycemia.

Keywords: Hypoglycemia, Ketosis, Diabetes Complications

1. Introduction

Ketogenic diets (KD), very low carbohydrate diets which evoke nutritional ketosis, have been a popular weight loss strategy for decades1. KDs are also becoming increasingly popular with diabetes patients2, 3 and healthcare professionals4, 5, due to their efficacy in reducing HbA1c and body weight, as well as improving lipid profiles 6–8. However, KDs have been associated with increased frequency of hypoglycemia in T1DM9 and T2DM7. The association between KDs and hypoglycemia has largely been attributed to the glucose lowering effects of KDs, yet there is evidence that KDs can also adversely affect hypoglycemic counter-regulation10. The present study was conducted to test the effects of consuming a KD on the physiological responses to both neuroglucopenia and insulin-induced hypoglycemia, and the results suggest that both are significantly altered in mice fed a KD.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Pennington Biomedical Research Center. Male C57BL/6J wild-type mice 8-12 weeks of age were fed a KD (Bio-Serv; F3666; 3% carbohydrate, 5% protein, 92% fat) ad lib for either 7 days (7d-KD) or 21 days (21d-KD). Littermate controls (7d-Chow; 21d-Chow) were fed Purina 5001 Rodent Laboratory Chow (58% carbohydrate, 29% protein, 13% fat).

2.2. Hormones and Metabolite Assays

Serum glucagon and corticosterone concentration were determined by ELISA (10-1281-01, Mercodia, Winston Salem, NC and K014-H1, Arbor, Ann Arbor, MI). Serum Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) concentration was determined by colorimetric assay (700190, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Blood glucose measurements were made by hand held glucometer (Contour Next, Bayer). BHB and fasting glucose levels were measured following a 4-5 hour fast, at ≈ 13:30.

2.3. Neuroglucopenia via intracerebroventricular (ICV) 2-deoxyglucose (2DG)

Following a 4-hour fast, mice were administered 2DG (1mg/mouse) or saline ICV via a surgically implanted indwelling cannula (0.3mm posterior and 1.0mm lateral to lambda, 2.5mm ventral to skull). Blood glucose was measured just prior to injection and again 30 minutes later. Trunk blood was collected 30 minutes post-injection. The response to neuroglucopenia was assessed in 4 groups of mice (saline and 2DG injected 21d-KD and 21d-Chow mice; n=9-12/group).

2.4. Hypoglycemic ITT

Following a 4-5 hour fast, 7d-KD and 7d-Chow mice (n=8-10/group) received an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of insulin, (Humulin R, Lilly USA Indianapolis, IN) at a variable dose in order to induce hypoglycemia (blood glucose: 40-60 mg/dL) for 30 minutes. Blood glucose levels were assayed at −15, 0, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes relative to insulin administration, and trunk blood was collected 60 minutes post-injection.

2.5. Data analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Group differences were determined via unpaired t-test or Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test with p-values ≤ 0.05 consider statistically significant.

3. Results

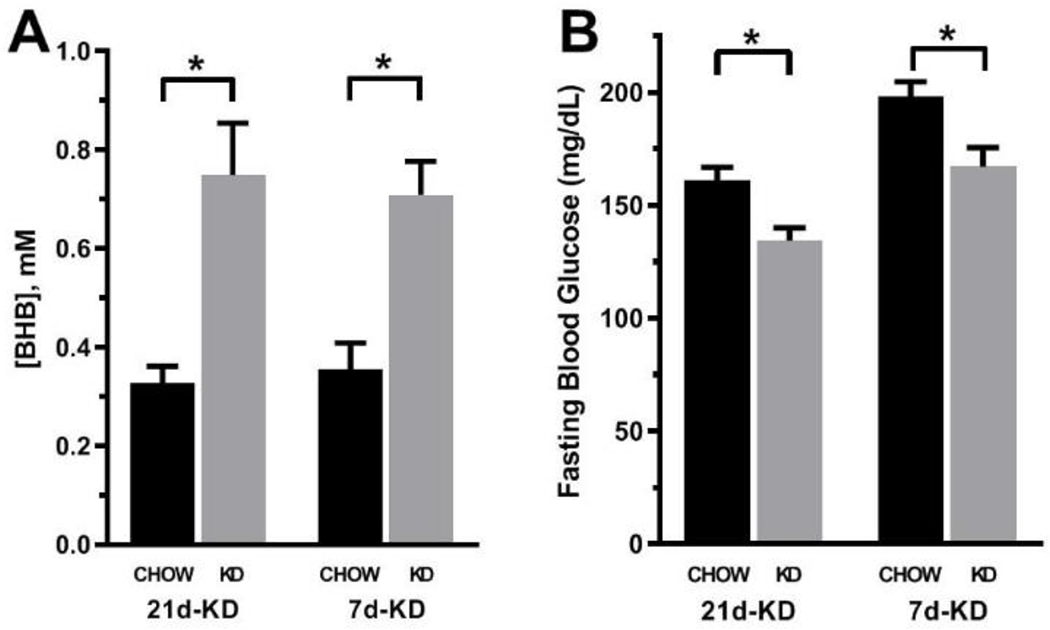

As expected, mice fed either a 7d-KD or a 21d-KD had lower fasting blood glucose levels relative to chow fed littermate controls (Figure 1A). KD fed mice also experienced ketosis as indicated by increased serum levels of BHB relative to chow fed control mice (Figure 1B). There was no difference in BHB levels between mice fed a 7d-KD versus a 21d-KD (p=0.939). 21d-KD mice experienced a 4 % weight loss compared to control mice, but this change was not statistically significant (p=0.1841). There was no appreciable difference in body weight between 7d-KD and 7d-Chow mice.

Figure 1. Feeding a ketogenic diet for either 7 or 21 days leads to similar levels of nutritional ketosis and reductions in fasting glucose levels in mice.

Mice fed a ketogenic diet (KD) for either 7 days (7d-KD) or 21 days (21d-KD) both displayed significantly elevated serum β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations [A] on the final day of the diet relative to chow fed controls (p=0.0047 and 0.0006, respectively). Concurrent with this nutritional ketosis, both 7d-KD and 21d-KD mice had significantly reduced fasting glucose concentrations [B] relative to chow fed controls (p= 0.0488 and 0.0020, respectively). Data were analyzed via two way ANOVA. Group differences were determined via Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (7d-KD: n=10-12/group, 21d-KD: n=21-23/group). *- p ≤ 0.05

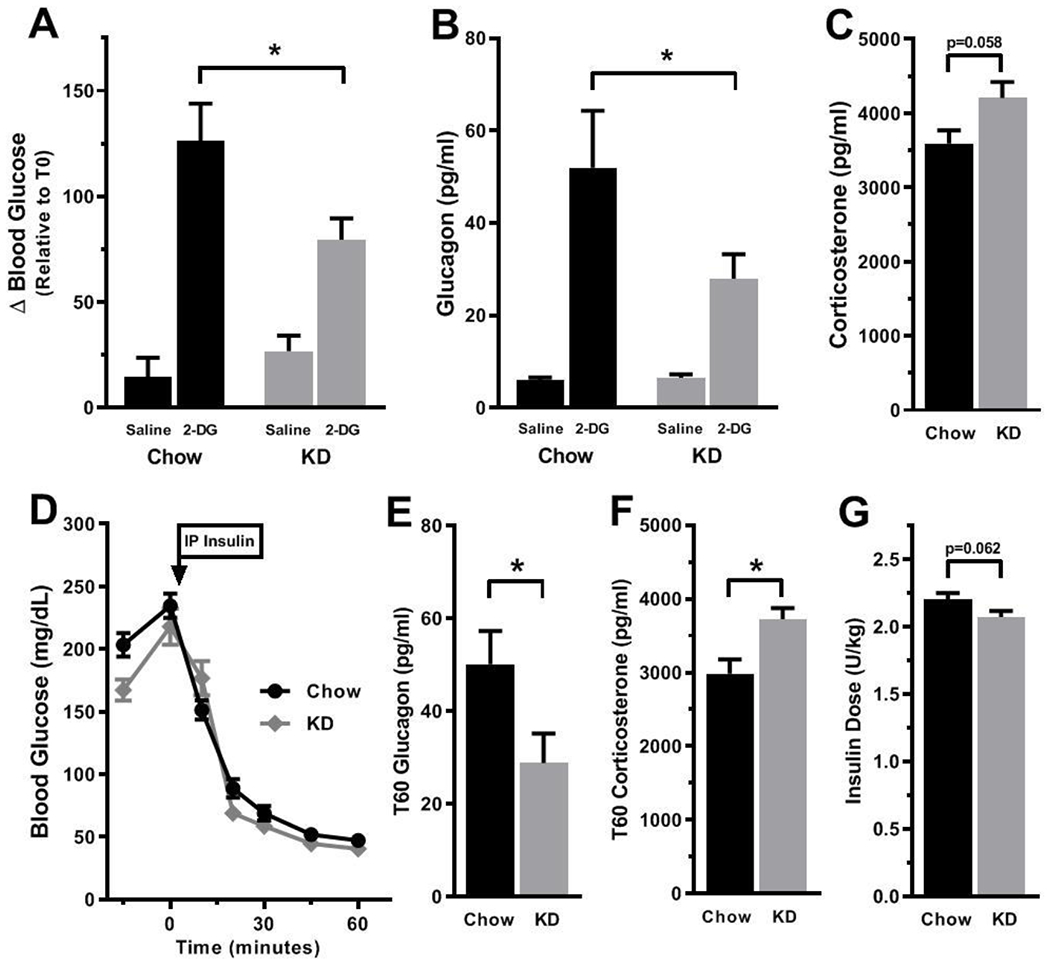

21d-KD mice experienced a significant blunting in the physiological response to 2DG induced neuroglucopenia, reflected by a 46% and 37% decrease in serum glucagon levels and blood glucose, respectively, relative to chow fed mice (Figure 2A–B; Glucagon: 27.9±5.3 and 52.0±12.3 pg/mL respectively, p=0.0123; Delta glucose relative to baseline: 79.5±10.1 and 126.50±17.4 mg/dL respectively, p=0.0111). 21d-KD mice experienced a 17% increase in 2DG induced corticosterone release, but this change was not statistically significant (Figure 2C; p=0.0584) Despite nearly identical exposure to hypoglycemia during the ITT (Figure 2D), 7d-KD mice experienced a 43% reduction in hypoglycemia-induced glucagon release relative to 7d-Chow mice (Figure 2E; 28.8±6.4 vs. 50.1±7.2 pg/mL; p=0.0438), and a 25% increase in corticosterone release relative to controls (Figure 2F; 2982±196 vs. 3723±152 pg/mL; p=0.0078). There was no significant difference in the insulin dose used to achieve hypoglycemia in 7d-KD versus 7d-Chow mice (Figure 2G).

Figure 2. Mice fed a ketogenic diet have altered neuroendocrine responses to both neuroglucopenia and insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

Mice fed a ketogenic diet for 21 days display blunted counter-regulatory responses to neuroglucopenia induced by intracerebroventricular administration of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), as indicated by a significant reduction in both 2-DG induced increases in blood glucose [A] and serum glucagon concentrations [B] relative to 2-DG treated chow fed controls (p=0.0111 and 0.0123, respectively). Concurrent with this reduction in glucagon levels, an increase in 2DG induced corticosterone release was observed, but this change was not statistically significant [C]. Similarly, mice fed a ketogenic diet for 7 days displayed altered counter-regulatory hormone release in response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Despite nearly identical exposure to hypoglycemia [D], mice fed a ketogenic diet for 7 days had significantly reduced hypoglycemia-induced glucagon levels [E] and significantly increased corticosterone levels [F] relative to chow fed controls measured 60 minutes following insulin administration (p=0.0438 and 0.0078, respectively). Although a slightly lower dose of insulin was needed to achieve appropriate levels of hypoglycemia in KD mice, this difference was not statistically significant [G]. Data were analyzed via two way ANOVA or unpaired t-tests where appropriate. Group differences were determined via Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test [A and B] n=8-10/group (7 day ketogenic diet) and 11-12/group (21 day ketogenic diet). *- p ≤ 0.05

4. Discussion

KDs are also being increasingly touted as a highly effective first line treatment for metabolic syndrome and diabetes 5,11–14. Yet concerns still remain regarding whether KDs increase the risk for hypoglycemia in both T1DM and T2DM7, 9. The major findings of our study are that mice fed a KD displayed impaired glucagon release in response to either insulin-induced hypoglycemia or neuroglucopenia. If a similar effect exists in humans, utilizing a KD to treat diabetes would blunt a hormonal response that is critical for preventing life-threating iatrogenic hypoglycemia in diabetes patients. Curiously, concurrent with the blunted glucagon response we observed an increase in hypoglycemia-induced corticosterone release in KD fed mice. Since corticosterone is not critical for acute recovery from hypoglycemia15, this may reflect an adaptation directed at prevention of long-term hypoglycemia during carbohydrate restriction.

Although the underlying mechanism driving our observed alterations in hypoglycemic counter-regulation is unclear, adaptive alterations in cerebral substrate preference could explain our results. Consuming a KD has been shown to cause shifts in cerebral metabolism that are indicative of increased capacity for the metabolism of non-glucose substrates, such as acetate and ketones, in both humans16 and rodents17. Increased cerebral acetate utilization in humans is associated with increased susceptibility to either insulin-induced hypoglycemia18 or fasting-induced hypoglycemia19. Furthermore, consuming a KD leads to a blunting of the glycemic response to glucagon administered during acute hypoglycemia10, presumably due to KD-induced reductions in hepatic glycogen content, which has been demonstrated in mice20. Thus during a ketogenic diet, as the brain adapts to utilizing alternative energy substrates as well as to reduced hepatic glycogen content, a compensatory alteration in glucose counter-regulation may occur.

In conclusion, we show that consuming a KD leads to altered hypoglycemia-induced glucagon and corticosterone release in mice. Thus, further characterization of the effects of KDs on glucose counter-regulation in humans is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported in part by ADA 1-15-JF-37 from the American Diabetes Association and U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Diabetes Association or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

References Cited:

- 1.Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. Jama. 2005;293(1): 43–53; doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers MA, Gal RL, Connor CG, et al. Eating patterns and food intake of persons with type 1 diabetes within the T1D exchange. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2018;141: 217–228; doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cresswell P, Krebs J, Gilmour J, Hanna A, Parry-Strong A. From ‘pleasure to chemistry’: the experience of carbohydrate counting with and without carbohydrate restriction for people with Type 1 diabetes. J Prim Health Care. 2015;7(4): 291–298; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base. Nutrition. 2015;31(1): 1–13; doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lennerz BS, Barton A, Bernstein RK, et al. Management of Type 1 Diabetes With a Very Low–Carbohydrate Diet. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6): e20173349; doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirk JK, Graves DE, Craven TE, Lipkin EW, Austin M, Margolis KL. Restricted-carbohydrate diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(1): 91–100; doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5): 731–754; doi: 10.2337/dci19-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turton JL, Raab R, Rooney KB. Low-carbohydrate diets for type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3): e0194987; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leow ZZX, Guelfi KJ, Davis EA, Jones TW, Fournier PA. The glycaemic benefits of a very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus may be opposed by increased hypoglycaemia risk and dyslipidaemia. Diabet Med. 2018; doi: 10.1111/dme.13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranjan A, Schmidt S, Damm-Frydenberg C, et al. Low-Carbohydrate Diet Impairs the Effect of Glucagon in the Treatment of Insulin-Induced Mild Hypoglycemia: A Randomized Crossover Study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1): 132–135; doi: 10.2337/dc16-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancy WS Jr., Foy M, Chalecki AM, Vernon MC, Westman EC. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab (Load). 2005;2: 34; doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyde PN, Sapper TN, Crabtree CD, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome independent of weight loss. JCI Insight. 2019;4(12); doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein RK. Dr. Bernstein’s diabetes solution : the complete guide to achieving normal blood sugars. [4th ed. New York: Little, Brown and Co; 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis E, Runyan K. The Ketogenic Diet for Type 1 Diabetes. Cheyenne, Wyoming: Gutsy Badger Publishing; 2017; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprague JE, Arbelaez AM. Glucose counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2011;9(1): 463–473; quiz 474–465; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bluml S, Shic F, Lai CL, Yahya K, Lin A, Ross B. Glutamate–glutamine cycling in epileptic patients on ketogenic diets In Proceedings, 10th International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2002;1: 417; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melø TM, Nehlig A, Sonnewald U. Neuronal–glial interactions in rats fed a ketogenic diet. Neurochemistry International. 2006;48(6–7): 498–507; doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulanski BI, De Feyter HM, Page KA, et al. Increased Brain Transport and Metabolism of Acetate in Hypoglycemia Unawareness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(9): 3811–3820; doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougal DH, Darpolor MM, DuVall MA, et al. Glial acetate metabolism is increased following a 72-h fast in metabolically healthy men and correlates with susceptibility to hypoglycemia. Acta diabetologica. 2018;55(10): 1029–1036; doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purhonen J, Rajendran J, Mörgelin M, et al. Ketogenic diet attenuates hepatopathy in mouse model of respiratory chain complex III deficiency caused by a Bcsll mutation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1): 957; doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]