Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether the onset of polymyositis (PM)/dermatomyositis (DM)-associated interstitial lung disease (ILD) is influenced by season and residence in the context of myositis-specific autoantibodies.

Methods

For patients with PM/DM-associated ILD enrolled in a multicentre cohort, 365 and 481 patients were eligible for seasonal and geographical analysis, respectively, based on the availability of reliable clinical information. The patients were divided into three groups: (1) anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibody-positive patients, (2) anti-aminoacyl tRNA synthetase (anti-ARS) antibody-positive patients and (3) patients negative for those antibodies. Seasonality was assessed by the Rayleigh test. Distance from residence to the nearest waterfront was measured on Google Map and was compared between groups by the exact Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Results

In anti-MDA5-positive patients, the disease developed more frequently in October–March (p=0.03), whereas a seasonal relationship was not found in the remaining two patient groups. Residence at disease onset in anti-MDA5-positive patients was significantly closer to the waterfront, especially to freshwater, compared with that in anti-ARS-positive or anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients (p=0.003 and 0.006, respectively).

Conclusions

Anti-MDA5-associated ILD occurred predominantly from October to March in individuals residing near freshwater, suggesting an environmental influence on the onset of this disease subset.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Dermatomyositis, Cytokines, Systemic sclerosis, Autoantibodies

INTRODUCTION

Polymyositis (PM) and dermatomyositis (DM) are idiopathic inflammatory myopathies that affect skeletal muscle, skin, joints and lungs to various degrees.1 Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with PM/DM.2 The aetiology of PM/DM still remains unknown, but it is believed that the disease occurs as a result of exposure to environmental factors in genetically susceptible individuals.3 The infection of microorganisms is known as an environmental trigger. For instance, a Swedish case–control study reported preceding infection as a risk factor for PM/DM.4 Another report demonstrated an increased prevalence of anti-Coxsackie B virus antibodies in patients with juvenile DM.5 In addition, there are several studies showing seasonal associations and spatial clustering of PM/DM onset in the disease subsets defined by myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs). Namely, seasonal patterns of PM/DM onset were different between patients with anti-Jo-1 antibody and those with anti-signal recognition particle antibody.6 Interestingly, the seasonal influence on disease onset in patients positive for anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (anti-ARS) antibodies, including anti-Jo-1, was different between African and non-African patients.7

Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibody is an MSA associated with rapidly progressive ILD, which often leads to fatal outcomes.8 9 Since MDA5 is a pattern recognition protein that works as a sensor for viral RNA,10 the autoimmune response to MDA5 might emerge as a consequence of the preceding infection of specific viruses. In this regard, a single-centre study reported that the majority of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive patients resided outside of urban areas and around a large river.11 To further explore the potential roles of environmental factors in the development of PM/DM-associated ILD in the context of MSAs, we examined seasonal and geographical influences on disease onset by taking advantage of the use of a multicentre retrospective Japanese Patients with Myositis-associated ILD (JAMI) cohort that involved 499 incident cases of PM-/DM-associated ILD.12

METHODS

Patients

The JAMI cohort enrolled adult incident patients with PM, classic DM or clinically amyopathic DM (CADM) who had ILD at diagnosis (UMIN000018663).12 Incident PM-/DM-associated ILD cases who visited their centres between October 2011 and October 2015 were enrolled. Forty-four JAMI participating centres are located across Japan, but there is a cluster in the Greater Tokyo region, serving about one-third of the national population (online supplemental figure 1). All centres were located in large cities, which are built around major rivers. Information on disease onset was carefully collected from individual patients by detailed history taking. The time (month, year) of onset was defined when any clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of PM/DM were first observed by the patients. Initial symptoms were classified into skin eruption (ie, specific and non-specific skin lesions with or without itch), respiratory symptoms (ie, cough and dyspnoea), fever, arthralgia, muscle symptoms (ie, weakness and myalgia) and others. Anti-MDA5 and anti-ARS antibodies were measured centrally using ELISA13 and RNA immunoprecipitation assay, respectively.

rmdopen-2020-001202s001.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

Seasonal analysis

The month of disease onset was analysed by the Rayleigh test, which handles circular data for testing uniformity.14 If the p value was <0.05, the null hypothesis where the incidence was uniform across the year was rejected, and disease onset had unimodal distribution, showing seasonality. To reduce the effects of small sample years, we included only patients who developed the disease within the last 5 years.

Geographical analysis

The JAMI database collected the postal code of the patient’s residence at the time of disease onset. We entered postal codes into the ‘My Map’ application of Google Map (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA, in collaboration with ZENRIN, Kitakyushu, Japan) and then measured the shortest straight-line distance from the postal code marker to the nearest waterfront, which was defined as any river, lake, pond or sea identifiable on Google Map on maximum enlargement. The only exclusion was small streams or ponds, which are not included in the river/lake list made by local governments. A representative map showing rivers, lakes, ponds and sea in the Tokyo–Yokohama area is shown in online supplemental figure 2. In some analyses, the water place was divided into freshwater and saltwater. The distance to the waterfront was categorised by multiplications of 1.75 km; this was based on the side length of the square when every area defined by a postal code was hypothesised to be square-shaped. The distribution of patients was compared between the groups using the exact Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Other statistical analyses

Continuous variables are shown as the median and 2.5–97.5 percentile, and were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used for survival analysis, and equality of survival curves was tested using the Breslow test. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.3.2 statistical software (http://cran.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

In this study, 365 and 481 patients were eligible for seasonal and geographical analysis, respectively. We then divided the patients into three groups: (1) anti-MDA5 antibody-positive patients, (2) anti-ARS antibody-positive patients and (3) patients negative for anti-MDA5 or anti-ARS antibody. Two patients with anti-MDA5 and anti-ARS antibodies together were excluded. As shown in table 1, anti-MDA5-positive patients were younger at disease onset, had shorter disease duration and were predominantly CADM, compared with anti-ARS-positive patients or anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients. In terms of initial symptoms, skin eruption was more frequent than respiratory symptoms in anti-MDA5-positive patients, whereas respiratory symptom was the most common initial symptom in anti-ARS-positive patients. Muscle symptom was infrequent in all three groups, and its frequency was the greatest in anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients. At diagnosis, serum creatine kinase level was lower and ferritin level was higher in anti-MDA5-positive patients than other two patient groups, while KL-6 was higher in anti-ARS-positive patients than others. Six-month survival rates were the lowest in anti-MDA5-positive patients, in whom approximately one-third died. There was no heterogeneity in demographic and clinical features, including initial symptoms as well as 6-month survival rates, between patients used for the seasonal analysis and the geographical analysis (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and 6-month survival of patients included in seasonal and geographical analysis, stratified by myositis-specific autoantibodies

| Variables | Seasonal analysis (n=365) | Geographical analysis (n=481) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-MDA5 (n=166) |

Anti-ARS (n=120) |

Anti-MDA5-/ARS- negative (n=79) |

P value | Anti-MDA5 (n=200) |

Anti-ARS (n=164) |

Anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative (n=117) |

P value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age at onset, years | 55 [29–78] | 59 [29–78] | 63 [33–84] | <0.01 | 56 [30–80] | 56 [27–78] | 61 [30–83] | 0.01 |

| Male | 64 (39%) | 35 (29%) | 30 (38%) | 0.22 | 70 (35%) | 45 (27%) | 46 (39%) | 0.10 |

| Disease duration, months | 2 [0–12] | 3 [0–23] | 3 [0–21] | <0.01 | 2 [0–21] | 3 [0–95] | 3 [0–73] | <0.01 |

| Initial symptoms | ||||||||

| Skin eruption | 93 (56%) | 16 (13%) | 36 (46%) | <0.01 | 112 (56%) | 21 (13%) | 48 (41%) | <0.01 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 34 (20%) | 62 (52%) | 15 (19%) | <0.01 | 41 (21%) | 79 (48%) | 28 (24%) | <0.01 |

| Fever | 21 (13%) | 13 (11%) | 10 (13%) | 0.91 | 24 (12%) | 19 (12%) | 12 (10%) | 0.92 |

| Arthralgia | 12 (7%) | 9 (8%) | 3 (4%) | 0.56 | 11 (6%) | 12 (7%) | 6 (5%) | 0.74 |

| Muscle symptoms | 4 (2%) | 8 (7%) | 12 (15%) | <0.01 | 6 (3%) | 15 (9%) | 16 (14%) | <0.01 |

| Others | 2 (1%) | 12 (10%) | 3 (4%) | <0.01 | 6 (3%) | 18 (11%) | 7 (6%) | 0.01 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| PM | 2 (1%) | 28 (23%) | 15 (19%) | <0.01 | 2 (1%) | 45 (27%) | 28 (24%) | <0.01 |

| Classic DM | 32 (19%) | 46 (38%) | 36 (46%) | 43 (22%) | 63 (38%) | 47 (40%) | ||

| CADM | 132 (80%) | 46 (38%) | 28 (35%) | 155 (78%) | 56 (34%) | 42 (36%) | ||

| Serum biomarkers | ||||||||

| CRP, mg/dL | 1.0 [0.0–5.6] | 0.8 [0.0–21.6] | 0.4 [0.0–26.3] | 0.08 | 0.9 [0.0–5.7] | 0.8 [0.0–20.1] | 0.4 [0.0–20.3] | 0.02 |

| CK, IU/L | 147 [33–3209] | 419 [31–4142] | 414 [48–7505] | <0.01 | 140 [25–2925] | 410 [32–4165] | 337 [36–9378] | <0.01 |

| KL-6, U/mL | 766 [284–2491] |

954 [202–5074] |

669 [207–10 257] |

0.01 | 757 [263–2402] |

947 [224–5074] |

646 [176–6587] |

<0.01 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 670 [24–6783] | 223 [10–2386] | 186 [26–4808] | <0.01 | 668 [32–6420] | 191 [11–2278] | 210 [23–3766] | <0.01 |

| 6-month survival rates | 67% | 98% | 96% | <0.01 | 68% | 99% | 97% | <0.01 |

Continuous variables are shown as the median [2.5–97.5 percentile]. Categorical variables are shown as n (%). The p-value for diagnosis was calculated by Fisher’s exact test for a 3×3 table. Disease duration means duration from symptom onset to disease diagnosis. Initial symptoms were classified into skin eruption (ie, specific and non-specific skin lesions, and itch), respiratory symptoms (ie, cough and dyspnoea), fever, joint symptoms (ie, arthritis and arthralgia), muscle symptoms (ie, weakness and myalgia) and others. Six-month survival was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method.

ARS, aminoacyl tRNA synthetase; CADM, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C reactive protein; DM, dermatomyositis; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen-6; MDA5, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; PM, polymyositis.

Seasonal analysis

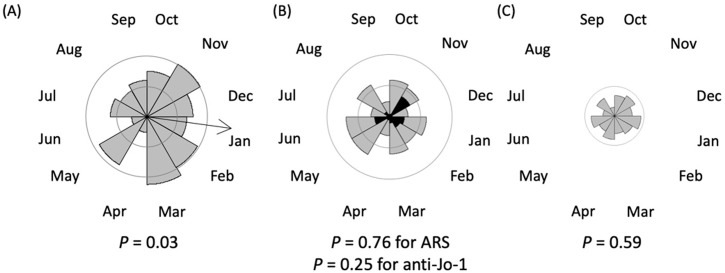

In the overall population, seasonality was not statistically significant (p=0.10). Figure 1 shows rose diagrams in individual MSA groups. In anti-MDA5-positive patients, the month of disease onset was not randomly distributed and peaked in January with an epidemic period between October and March (p=0.03). The seasonal analysis in anti-MDA5-positive patients was additionally carried out each year starting from October 2010 (online Supplemental figure 3). There were some variations in the seasonality depending on the year, but the number of patients was too small to conduct statistical analysis year by year. In contrast, seasonality was not detected in anti-ARS-positive patients or anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients. Thirty-two patients with anti-Jo-1 antibody were investigated separately, but again, there was no seasonality.

Figure 1.

Seasonality analysis. Rose diagrams of the Rayleigh test showing the number of patients categorised by months of disease onset. The radius of each sector of the circle indicates the number of patients. Inside and outside circles represent 10 and 20 cases, respectively. An arrow indicates the mean direction of the circular data for significant seasonality. (A) Anti-MDA5-positive patients. (B) Anti-ARS-positive patients. Black sectors indicate numbers of patients with anti-Jo-1 antibody. (C) Anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients.

ARS, aminoacyl tRNA synthetase; MDA5, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5.

Geographical analysis

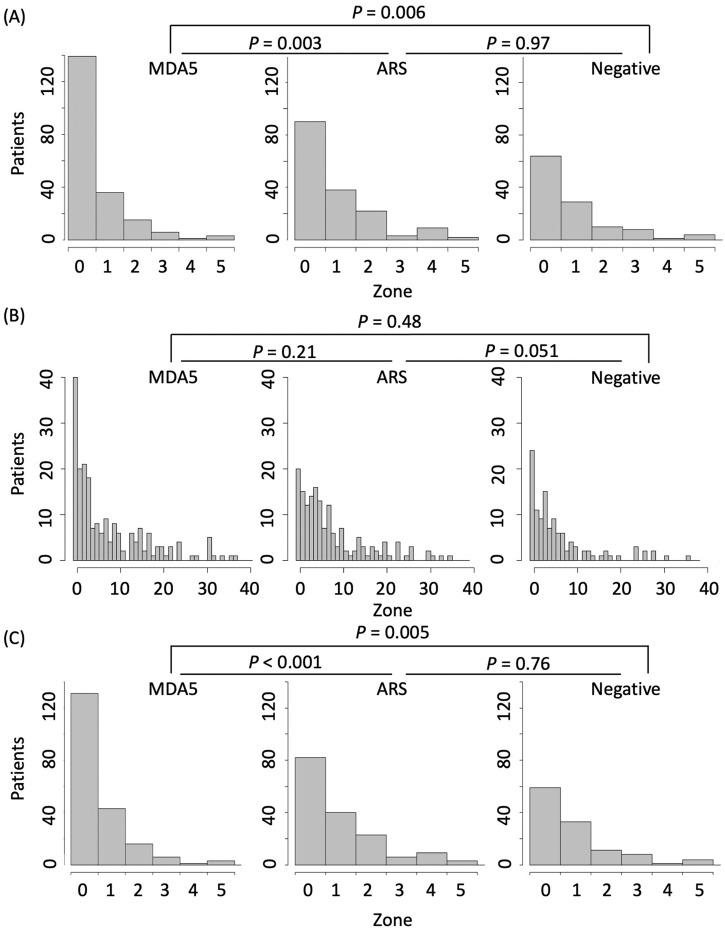

A representative Google Map image of the residence of patients with PM-/DM-associated ILD is shown in online supplemental figure 4. As shown in figure 2A, the residence of anti-MDA5-positive patients was significantly closer to any major waterfront than that of anti-ARS-positive patients or anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients (p=0.003 and 0.006, respectively). When the waterfront was restricted to seawater, a significant difference was lost (figure 2B). In contrast, the distance from patient residence to freshwater was significantly different between anti-MDA5-and anti-ARS-positive patients or anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative patients (p<0.001 and 0.005, respectively) (figure 2C). There was no difference in the distance between the anti-ARS-positive and anti-MDA5-/ARS-negative groups.

Figure 2.

Distance from residential place to the nearest waterfront. Histograms showing the number of patients hierarchised by the distance from the residential place at disease onset to the nearest waterfront. The distance was categorised by multiplication of 1.75 km. Zone 0 covers the distance from 0 to 1.75 km, while Zone 1 covers the distance from 1.75 to 3.50 km. P values were calculated by exact Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (A) Distance to any waterfront. (B) Distance to seawater. (C) Distance to freshwater (river, lake or pond).

Clinical characteristics of patients stratified by season and residence at disease onset in anti-MDA5-positive patients

We further examined potential differences in clinical presentation among four patient groups stratified by season and residence at disease onset: disease onset in either April–September or October–March and residing either close to freshwater (≤1.75 km) or far from freshwater (>1.75 km) in anti-MDA5-positive patients. When clinical characteristics were compared among the groups, there were no statistically significant differences except for fever as the initial symptom, which was more frequent in patients who developed the disease in October–March and resided in the place close to freshwater (online supplemental table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in cumulative survival rates between the four groups (online supplemental figure 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that anti-MDA5-associated ILD occurs predominantly from October to March in individuals residing near freshwater, although there was no difference in clinical presentation in patient groups stratified by season or residence at disease onset. This finding suggests that environmental triggers may play roles in eliciting anti-MDA5-associated ILD. Of the many potential environmental factors that may be associated with the onset of PM/DM, infection could be a plausible explanation for this time-space clustering at disease onset.4 5 In this regard, it has been recognised that some infectious agents can be transmitted by vectors inhabiting near freshwater, whose activity depends on the season, such as mosquitos and migratory birds,15 16 although it is just a hypothesis of potential environmental factors related to anti-MDA5-associated ILD. On the other hand, recognition of viral RNA by MDA5 initiates activation of NF-κβ and production of type I interferon (IFN) and other proinflammatory cytokines.17 In fact, several inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IFN-α, IFN-γ, TNF-α and IP-10, were upregulated in the circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-associated ILD.18 19 The simultaneous onset of DM rashes and ILD with or without skeletal muscle involvement in anti-MDA5-positive patients might be explained by triggering onset by infection through the respiratory tract. MDA5 is known to recognise RNA viruses, including picornavirus (eg, Coxsackievirus), paramyxovirus, reovirus, dengue virus and West Nile virus.20 21 Interestingly, coronaviruses that cause acute respiratory distress syndrome have mechanisms circumventing the innate antiviral response mediated by MDA5.22 In fact, high serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were detected in both anti-MDA5-associated ILD18 19 and acute respiratory insufficiency caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome/Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronaviruses23 24 and even COVID-19.25 26 It is a future task to examine whether preceding virus infection contributes to the onset of rapidly progressive anti-MDA5-associated ILD.

This study has several limitations. First, disease onset was defined by any symptom potentially related to PM/DM, while previous studies examining seasonal clustering of PM/DM onset considered muscle weakness as disease onset.6 7 This may be one of the reasons for the lack of seasonal clustering in anti-ARS-positive patients in this study. Incidentally, more than half of the patients enrolled in JAMI lacked muscle symptoms. Second, the reliability of history taking is a matter of concern. In this regard, in the JAMI cohort, the median disease duration at diagnosis was only 2 months,12 which was much shorter than other studies, resulting in an improbable role of recall bias. Finally, it was difficult to examine environmental triggers related to residence at disease onset. This is a common problem in environmental factor research.27 Detailed behaviour monitoring before disease onset might be critical but appears impractical.

In conclusion, we found seasonal and geographical clustering at the onset of anti-MDA5-associated ILD. This might promote further studies investigating environmental triggers of this devastating condition.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject

Some disease subsets of polymyositis/dermatomyositis defined by myositis-specific autoantibodies showed seasonal patterns of disease onset.

What does this study add

The onset of anti-MDA5-associated interstitial lung disease is influenced by the season and place of residence.

How might this impact clinical practice or future developments

Further studies investigating the environmental triggers of anti-MDA5-associated interstitial lung disease may provide useful clues for aetiology.

Acknowledgments

Other investigators of the JAMI: Yasushi Kawaguchi (Tokyo Women’s Medical University), Atsushi Kawakami (Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences), Kei Ikeda (Chiba University Hospital), Yohei Kirino (Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine), Yoshinori Tanino (Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine), Takahiro Nunokawa (Tokyo Metropolitan Tama Medical Center), Yuko Kaneko (Keio University School of Medicine), Katsuaki Asakawa (Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital), Taro Ukichi (Jikei University School of Medicine), Shinjiro Kaieda (Kurume University School of Medicine), Taio Naniwa (Nagoya City University School of Medicine), Yutaka Okano (Kawasaki Municipal Kawasaki Hospital), Yukie Yamaguchi (Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine), Yoshinori Taniguchi (Kochi Medical School, Kochi University), Jun Kikuchi (Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University), Makoto Kubo (Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine), Masaki Watanabe (Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University), Tatsuhiko Harada (Nagasaki University School of Medicine), Taisuke Kazuyori (The Jikei University School of Medicine Katsushika Medical Center), Hideto Kameda (Toho University Ohashi Medical Center), Makoto Kaburaki (Toho University School of Medicine), Yasuo Matsuzawa (Toho University Medical Center, Sakura Hospital), Shunji Yoshida (Fujita Health University School of Medicine), Yasuko Yoshioka (Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital), Takuya Hirai (Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital), Yoko Wada (Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences), Koji Ishii (Faculty of Medicine, Oita University), Sakuhei Fujiwara (Faculty of Medicine Oita University), Takeshi Saraya (Kyorin University), Kozo Morimoto (Fukujuji Hospital, Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association), Tetsu Hara (Hiratsuka Kyosai Hospital), Hiroki Suzuki (Saiseikai Yamagata Saisei Hospital), Hideki Shibuya (Tokyo Teishin Hospital), Yoshinao Muro (Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine), Ryoichi Aki (Kitasato University School of Medicine), Takuo Shibayama (National Hospital Organization Okayama Medical Center), Shiro Ohshima (National Hospital Organization Osaka Minami Medical Center), Yuko Yasuda (Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital), Masaki Terada (Saiseikai Niigata Daini Hospital) and Yoshie Kawahara (Keiyu Hospital).

Footnotes

Contributors: NN, SS, and MK conceived and designed the study; NN and KM analysed the data; SS, KM, TG, MK and JAMI investigators contributed data collection/analysis tools; and all authors wrote the paper.

Funding: This work was supported in part by a research grant for intractable diseases from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: SS holds the patent for the anti-MDA5 antibody measurement kit; MK holds the patent for the anti-MDA5 antibody measurement kit and has received consulting fees, speaking fees and research grants from Abbvie, Actelion, Asahi Kasei, Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Chugai, Eisai, Corbus, CSL Behring, Janssen, MBL, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida, Nippon Shinyaku, Novartis, Pfizer, Ono, Reata, Takeda, Teijin and UCB. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethical approval: JAMI was approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating centre (Nippon Medical School, Tokyo, Japan; 26-03-434) and by individual participating centres.

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tieu J, Lundberg IE, Limaye V. Idiopathic inflammatory myositis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30:149–68. 10.1016/j.berh.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson C, Pinal-Fernandez I, Parikh R, et al. Assessment of mortality in autoimmune myositis with and without associated interstitial lung disease. Lung 2016;194:733–7. 10.1007/s00408-016-9896-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller FW, Lamb JA, Schmidt J, et al. Risk factors and disease mechanisms in myositis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:255–68. 10.1038/nrrheum.2018.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svensson J, Holmqvist M, Lundberg IE, et al. Infections and respiratory tract disease as risk factors for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A population-based case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1803–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen ML, Pachman LM, Schneiderman R, et al. Prevalence of coxsackie B virus antibodies in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1365–70. 10.1002/art.1780291109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leff RL, Burgess SH, Miller FW, et al. Distinct seasonal patterns in the onset of adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathy in patients with anti-Jo-1 and anti-signal recognition particle autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:1391–6. 10.1002/art.1780341108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar K, Weinberg CR, Oddis CV, et al. Seasonal influence on the onset of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies in serologically defined groups. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2433–8. 10.1002/art.21198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1571–6. 10.1002/art.21023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Sato S, et al. Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is associated with rapidly progressive lung disease and poor survival in US patients with amyopathic and myopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:689–94. 10.1002/acr.22728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H, Takahasi K, Fujita T. RIG-I-like receptors: Cytoplasmic sensors for non-self RNA. Immunol Rev 2011;243:91–8. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muro Y, Sugiura K, Hoshino K, et al. Epidemiologic study of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis and anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies in central Japan. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R214 10.1186/ar3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato S, Masui K, Nishina N, et al. Initial predictors of poor survival in myositis-associated interstitial lung disease: A multicentre cohort of 497 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:1212–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/key060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato S, Hoshino K, Satoh T, et al. RNA helicase encoded by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is a major autoantigen in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: Association with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2193–200. 10.1002/art.24621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.13 Fischer NI. Statistical analysis of circular data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993: 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilibic-Cavlek T, Savic V, Petrovic T, et al. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of West Nile and Usutu virus infections in Southern Europe. Front Vet Sci 2019;6:437 10.3389/fvets.2019.00437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatesh D, Poen MJ, Bestebroer TM, et al. Avian influenza viruses in wild birds: Virus evolution in a multihost ecosystem. J Virol 2018;92:e00433–18. 10.1128/JVI.00433-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dias Junior AG, Sampaio NG, Rehwinkel J. A balancing act: MDA5 in antiviral immunity and autoinflammation. Trends Microbiol 2019;27:75–85. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horai Y, Koga T, Fujikawa K, et al. Serum interferon-alpha is a useful biomarker in patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol 2015;25:85–9. 10.3109/14397595.2014.900843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gono T, Kaneko H, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Cytokine profiles in polymyositis and dermatomyositis complicated by rapidly progressive or chronic interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:2196–203. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoneyama M, Onomoto K, Jogi M, et al. Viral RNA detection by RIG-I-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol 2015;32:48–53. 10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Q, Hato SV, Langereis MA, et al. MDA5 detects the double-stranded RNA replicative form in picornavirus-infected cells. Cell Rep 2012;2:1187–96. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding Z, Fang L, Yuan S, et al. The nucleocapsid proteins of mouse hepatitis virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus share the same IFN-beta antagonizing mechanism: Attenuation of PACT-mediated RIG-I/MDA5 activation. Oncotarget 2017;8:49655–70. 10.18632/oncotarget.17912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He L, Ding Y, Zhang Q, et al. Expression of elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in SARS-CoV-infected ACE2+ cells in SARS patients: Relation to the acute lung injury and pathogenesis of SARS. J Pathol 2006;210:288–9. 10.1002/path.2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faure E, Poissy J, Goffard A, et al. Distinct immune response in two MERS-CoV-infected patients: Can we go from bench to bedside? PLoS One 2014;9:e88716 10.1371/journal.pone.0088716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown N, et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet Resp Med 2020;395:1033–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah M, Targoff IN, Rice MM, et al. Ultraviolet radiation exposure is associated with clinical and autoantibody phenotypes in juvenile myositis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1934–41. 10.1002/art.37985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2020-001202s001.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)