Abstract

Background

Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is the most common extra-articular manifestation in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). C-VIEW investigates the impact of the Fc-free TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (CZP) on AAU flares in patients with active axSpA at high risk of recurrent AAU.

Methods

C-VIEW (NCT03020992) is a 96-week ongoing, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 study. Included patients had an axSpA diagnosis, a history of recurrent AAU (≥2 AAU flares, ≥1 flare in the year prior to study entry), HLA-B27 positivity, active disease, and failure of ≥2 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients received CZP 400 mg at Weeks 0/2/4, then 200 mg every 2 weeks up to 96 weeks. This 48-week pre-planned interim analysis compares AAU flare incidence in the 48 weeks before and after initiation of CZP treatment, using Poisson regression to account for possible within-patient correlations.

Results

In total, 89 patients were included (male: 63%; radiographic/non-radiographic axSpA: 85%/15%; mean axSpA disease duration: 8.6 years). During 48 weeks’ CZP treatment, 13 (15%) patients experienced 15 AAU flares, representing an 87% reduction in AAU incidence rate (146.6 per 100 patient-years (PY) in the 48 weeks pre-baseline to 18.7 per 100 PY during CZP treatment). Poisson regression analysis showed that the incidence rate of AAU per patient reduced from 1.5 to 0.2 (p<0.001). No new safety signals were identified.

Conclusions

There was a significant reduction in the AAU flare rate during 48 weeks of CZP treatment, indicating that CZP is a suitable treatment option for patients with active axSpA and a history of recurrent AAU.

Keywords: uveitis, TNF inhibitor, axial spondyloarthritis, extra-articular manifestations

INTRODUCTION

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily manifests in the axial skeleton (sacroiliac joints and spine). However, approximately 30% of patients with axSpA also have extra-articular manifestations, including psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and acute anterior uveitis (AAU).1 The overall prevalence of these extra-articular manifestations is largely similar for patients with radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA: axSpA with definitive signs of structural damage of the sacroiliac joints on X-ray, who fulfil the modified New York classification criteria)2 and non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA: axSpA without definitive signs of structural damage on X-ray), although uveitis appears to be more prevalent in r-axSpA.3–5

Key messages.

What is already known about the subject?

Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is the most common extra-articular manifestation in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and has an important influence on quality of life.

In some patients, AAU attacks recur very frequently. In these patients, it is essential that their axSpA treatment also effectively reduces the risk of recurrent AAU.

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapies are highly effective in the treatment of axSpA; however, studies exploring the impact of TNFi on AAU in patients across the full axSpA spectrum are scarce.

What does this study add?

This is the first study to report data on the impact of the PEGylated Fc-free TNFi certolizumab pegol (CZP) on the incidence of AAU flares in patients with active axSpA, including radiographic and non-radiographic axSpA, and a history of recurrent AAU.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The significant reduction in AAU flare incidence and improvement in axSpA symptoms indicates that CZP is a suitable treatment option for patients across the full axSpA spectrum with recurrent AAU.

AAU, inflammation of the anterior uveal tract, has an incidence rate of about 36.8 per 100 000 person-years in the USA.6 AAU is strongly associated with the presence of the HLA-B27 gene, and HLA-B27-positive patients have an increased risk of recurring AAU.7–10 In patients with axSpA, AAU is the most common extra-articular manifestation.11 12 The prevalence of AAU increases with disease duration and was estimated to be between 21% and 33% in patients with r-axSpA1 4 5 13 and 12% in patients with nr-axSpA.5 AAU is associated with a significant burden, including blurred vision, photophobia, pain, risk of complications, and an important decrease in quality of life.14 15 Recurrent AAU may lead to glaucoma, cataract development, and visual loss.16

Conventional treatment for AAU is aimed at controlling ocular inflammation to avoid complications and includes intensive topical treatment with corticosteroid eyedrops and mydriatics. Although most cases of AAU respond well to standard topical treatment, this therapy may be insufficient for controlling inflammation in patients with highly refractory disease. In very severe cases, subconjunctival depot corticosteroid injections and sometimes even systemic corticosteroids are needed to treat the inflammation. However, chronic administration of topical corticosteroids is associated with adverse events such as cataract formation and glaucoma, while systemic corticosteroids could lead to osteoporosis and diabetes mellitus, rendering these unsuitable as long-term treatment for reducing the flare rate in patients with frequently recurring AAU.17 18 In contrast to intermediate or posterior uveitis, which often necessitates the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), these drugs are not indicated in AAU due to limited data on their efficacy19–21; nor do they treat the underlying disease (axSpA). Therefore, in axSpA patients with high disease activity and recurrent AAU,9 treatment which is effective for axSpA and also reduces the risk of AAU would be ideal.

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapies have been proven to be highly effective in the treatment of axial symptoms of axSpA.22 Furthermore, several TNFi treatments appear to effectively reduce the occurrence of AAU flares in patients with r-axSpA. This has been extensively described for adalimumab, infliximab, and golimumab, while there is still debate about the impact of the fusion receptor protein etanercept, as some studies suggest a risk of paradoxical AAU flares during treatment with this TNFi.23–31 Data on the effect of the PEGylated Fc-free TNFi certolizumab pegol (CZP) on the incidence of AAU in axSpA are limited; previous studies have reported mostly retrospective or post hoc analyses.32–35 Moreover, studies exploring the impact of TNFi treatment on AAU in patients across the full axSpA spectrum, including both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA, are scarce.

The aim of this study is to prospectively investigate the impact of the TNFi CZP on the frequency of AAU flares in patients with active axSpA and a recent history of recurrent AAU.

METHODS

Study design

AS0007/C-VIEW (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT03020992) is a 96-week, ongoing, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 study conducted in five countries in Europe (Czech Republic, Germany, The Netherlands, Poland, and Spain).

The study aimed to evaluate the impact of CZP on the incidence of AAU flares in patients with active axSpA and a recent history of recurrent AAU, by comparing the number of flares in the 96 weeks prior to and during CZP treatment. Here, we report results from a pre-planned interim analysis on the incidence of AAU flares during the first 48 weeks of CZP treatment (the treatment period) compared with the 48 weeks before baseline (the pre-treatment period).

The study was approved by institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at participating sites and was conducted in accordance with local regulations and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice requirements, based on the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Patients were eligible for study participation if they were ≥18 years of age, HLA-B27 positive, and had a diagnosis of axSpA, fulfilling the ASAS classification criteria.36 Patients with r-axSpA must have had evidence of sacroiliitis on X-ray (evaluated by local readers) meeting the modified New York classification criteria,2 while those with nr-axSpA had to have a C-reactive protein level above the upper limit of normal and/or evidence of sacroiliitis on MRI (evaluated by local readers) within the 3 months prior to baseline.36 At study entrance, patients were required to have active axSpA, defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score ≥4 and spinal pain (BASDAI item 2) ≥4, and previous inadequate response to ≥2 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Furthermore, patients must have had a documented history of AAU, diagnosed by an ophthalmologist, with at least two AAU flares in the past, of which one had to have occurred in the 52 weeks prior to screening. Eligible patients were permitted previous exposure to up to one TNFi biologic (for infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab, use in the 3 months prior to baseline was not permitted; for etanercept, use in the 28 days prior to baseline was not permitted). All patients provided informed consent to participate.

Study procedures and endpoints

Eligible patients received subcutaneous CZP 200 mg (loading dose of CZP 400 mg at baseline, Week 2 and Week 4) every 2 weeks (Q2W) up to Week 94. After the baseline visit (Week 0), study visits were scheduled for Weeks 2, 4, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84 and 96. As the study is ongoing, only results up to the Week 48 visit are reported here.

For details of historic uveitis flares (occurring in the 12 months prior to baseline), the patient’s treating ophthalmologist was contacted for information on the start and stop dates of the flare, affected eye, location (anterior/intermediate/posterior/pan), who made the diagnosis (ophthalmologist/other), severity grading, and treatment given (including start and stop dates). Information on the family history of uveitis and any additional information of importance regarding history of uveitis, any complications, and/or any surgical procedure(s) was also documented.

During the study, patients were asked to contact their ophthalmologist when they experienced any AAU flare symptoms. The occurrence of an AAU flare was confirmed by the ophthalmologist who recorded the duration (from start date of signs of AAU to end of AAU flare treatment) and treatment of the flare. The affected eye, location (anterior/intermediate/posterior/pan) and severity grading were also recorded if available. Flares on the same eye were considered separate only if the interval between them was more than 3 months (90 days). In addition, start date, stop date, route, dosage, duration, and frequency for any medication that was administered to the patient was documented. At each visit, AAU flares that had occurred since the last visit were evaluated.

The following axSpA-specific variables were also assessed at every study visit: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), ASDAS thresholds of improvement (major improvement [MI]: decrease of ≥2.0 units from baseline; clinically important improvement [CII]: decrease of ≥1.1 units from baseline), ASDAS inactive disease (ID; ASDAS <1.3), BASDAI, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 20%/40% and partial remission responses (ASAS20/40/PR), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index (BASFI), Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGADA), Physician’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PhGADA), total spinal pain, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL), ASAS Health Index (ASAS HI), and fatigue (BASDAI Q1).

Adverse events were recorded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, Version 19.0.

Statistical analysis

Assuming an average follow-up period of 1.5 years with a two-sided alpha level of 0.049 for the primary efficacy variable, a sample size of 86 would have 80% power to detect differences for a two-group comparison (prior and during CZP treatment), assuming that CZP treatment results in a ~50% reduction in flare rate. Due to the expected increase in statistical efficiency given that each subject serves as his/her own control in the primary efficacy analysis, the actual power for this study is assumed to be >80%.

Efficacy and safety variables were analysed for the Safety Set, which consists of all subjects who received at least one dose of CZP. The primary efficacy analysis consisted of a comparison of the frequency of AAU flares in the pre-study period with that observed during the study in patients at risk for a flare. It was assumed (and confirmed) that the frequency of AAU flares would follow a Poisson distribution. The analysis was, therefore, performed as a generalised estimating equation analysis for the Poisson outcome that takes into account the possible within-patient correlation (between the retrospective and prospective AAU flare counts). Although the protocol specified that there was no intention to stop the study early due to efficacy or futility on the basis of the interim results, a statistical approach to adjust for multiplicity of testing was employed where α=0.001 (out of the overall α=0.05) was spent in conjunction with this pre-specified interim analysis. The final analysis of the primary efficacy variable will be conducted at the reduced two-sided α-level of 0.049. Rate of flare during the study was calculated based on the number of cases per patient at risk.

Continuous axSpA-specific variables were summarised using the mean and SD of observed scores at baseline and subsequent visits. Dichotomous measures were summarised using the proportion of patients meeting outcome criteria at each study visit. Observed data are presented; no adjustment was made to account for missing data.

Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed for patients who had >1 and ≤1 AAU flare during the 48-week pre-baseline period, and for patients stratified by axSpA subclassification (r- or nr-axSpA).

All statistical analyses beyond the primary efficacy analysis are exploratory only. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 or above.

RESULTS

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 115 patients from 23 sites in Europe (Czech Republic, Germany, The Netherlands, Poland and Spain) were screened between 22 December 2016 and 25 September 2017, of whom 26 failed the screening process (25 did not meet eligibility criteria and one had an adverse event; Table S1). A total of 89 enrolled patients were included, of whom 63% were male and 85% had r-axSpA. The mean axSpA disease duration was 8.6 years (table 1). Four patients (4%) had previous exposure to a TNFi (etanercept) prior to the study, of whom three (3%) had exposure during the 48-week pre-study period. Seventeen patients (19%) used systemic corticosteroids in the 48-week pre-treatment period, of whom two (2%) still had exposure at baseline (table 1). For five patients (6%), the AAU flare was still ongoing at baseline. In total, 96% (85/89) patients completed the Week 48 visit, and the primary reason for discontinuation in the four patients not completing this visit was the occurrence of adverse events (abnormal sensation in eye, sarcoidosis, nasopharyngitis, and prostate cancer).

Table 1.

Baseline and disease characteristics for the Safety Set (N=89)

| CZP 200 mg Q2 W (N=89) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46.5 (11.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 56 (63%) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.3 (5.1) |

| Racial group: Caucasian, n (%) | 87 (98%) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Radiographic axSpA | 76 (85%) |

| Non-radiographic axSpA | 13 (15%) |

| Sacroiliitis on MRI or radiographs | 86 (97%) |

| Time since axSpA diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 8.6 (8.4) |

| HLA-B27 positive, n (%) | 89 (100%) |

| Uveitis history, n (%) | 89 (100%) |

| Time since onset of first uveitis flare (years), mean (SD) | 9.9 (9.0) |

| Number of uveitis flares in 48 weeks pre-baseline, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| Number of patients with active flare at baseline | 5 (6%) |

| Psoriasis history, n (%) | 3 (3%) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease history, n (%) | 0 |

| Prior medication exposure, n (%) | |

| TNFi* | 4 (4%) |

| TNFi use in the 48-week pre-baseline period | 3 (3%) |

| NSAIDs | 88 (99%) |

| Conventional DMARDs | 31 (35%) |

| Concomitant medication use at baseline, n (%) | |

| TNFi | 0 |

| NSAIDs | 10 (11%) |

| Conventional DMARDs | 0 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 2 (2%) |

| Systemic corticosteroid use, n (%)† | |

| 48-week pre-baseline period | 17 (19%) |

| 48-week treatment period | 6 (7%) |

| Tender joint count ≥1, n (%) | 59 (66%) |

| Swollen joint count ≥1, n (%) | 33 (37%) |

| CRP, mg/L, mean (SD) | 14.8 (26.8) |

| CRP > ULN, n (%) | 30 (34%) |

Patients were enrolled from the Czech Republic (n=35), Germany (n=6), the Netherlands (n=6), Poland (n=38), and Spain (n=4).

*Etanercept in all four patients.

†In total, 20 patients had exposure to systemic corticosteroids during the 48-week pre- and post-baseline periods. Some patients used systemic corticosteroids in both the pretreatment and treatment periods.

ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; ULN, upper limit of normal.

rmdopen-2019-001161s001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

Number and incidence of anterior uveitis flares

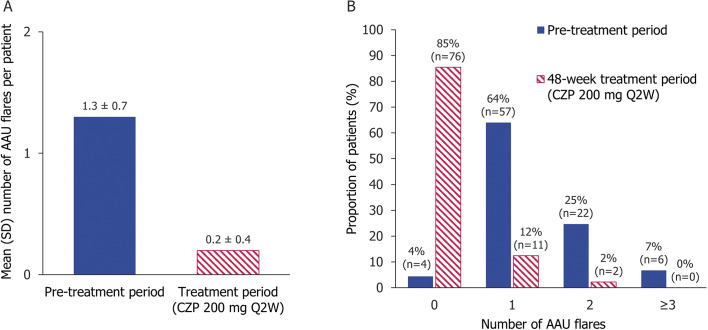

In the 48-week pretreatment period, the mean (SD) number of AAU flares across all patients was 1.3 (0.7) per patient, with no, one, two, and three or more AAU flares in 4% (4/89), 64% (57/89), 24% (22/89) and 7% (6/89) of patients, respectively. Four patients had an AAU flare before the 48-week pretreatment period but within the 52-week period.

During the first 48 weeks on CZP treatment, the mean (SD) numbers of flares per patient at risk reduced to 0.2 (0.4), with 12% (11/89) experiencing one AAU flare and only 2% (2/89) experiencing two flares (figure 1). No patient experienced more than two AAU flares during this observational period. Poisson regression analysis, accounting for within-patient correlation, showed that the incidence rate of AAU flares decreased from 1.5 (pre-study period) to 0.2 during the study (p<0.001), with a rate ratio (CZP/historical) of 0.1 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.2). Overall, during CZP treatment, the AAU incidence rate per 100 patient-years (PY) decreased from 146.6 (95% CI 121.5 to 175.3) to 18.7 per 100 PY (95% CI 10.5 to 30.9), a significant reduction of 87%.

Figure 1.

(A) Mean number of AAU flares pre- and post-baseline. (B) Proportion of patients experiencing AAU flares pre- and post-baseline. Safety Set (N=89). Four patients had an AAU flare in the 12 months prior to baseline but not during the 48-week pretreatment period. AAU, acute anterior uveitis; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

AAU flare incidence was also evaluated in subgroups of patients who had experienced ≤1 (n=61) and >1 (n=28) flares during the 48-week pre-study period. In patients who had ≤1 AAU flare in the pre-study period, AAU flare incidence decreased from 1.0 to 0.2, while in patients who had >1 AAU flare during the pre-study period, it decreased from 2.5 to 0.2 (Poisson regression analysis). The incidence rate per 100 PY decreased from 101.6 (95% CI 76.9 to 131.6) to 16.5 per 100 PY (95% CI 7.5 to 31.3) and from 244.6 (95% CI 188.0 to 312.9) to 23.5 per 100 PY (95% CI 8.6 to 51.2) in the ≤1 and >1 AAU flare subgroups, respectively.

Subgroup analysis of the AAU flare incidence for patients with r-axSpA and nr-axSpA revealed a similar reduction in incidence between the two subpopulations. In r-axSpA patients (n=76), the incidence decreased from 144.5 (95% CI 117.7 to 175.5) pre-study to 19.0 (95% CI 10.1 to 32.4) per 100 PY during the study. For nr-axSpA patients (n=13), the incidence decreased from 158.9 (95% CI 95.7 to 248.1) to 17.2 (95% CI 2.1 to 62.2) per 100 PY.

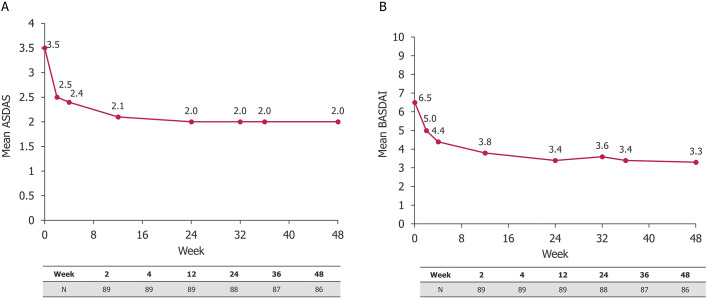

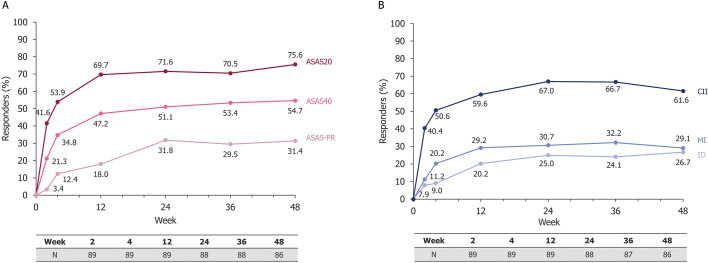

Disease activity and other outcomes

Between baseline and Week 48, axSpA disease activity improved, with ASDAS decreasing from a mean (SD) of 3.5 (0.9) at baseline to 2.0 (0.9) at Week 48, and the BASDAI from 6.5 (1.5) to 3.3 (2.1) (figure 2). The proportion of patients achieving ASAS20, ASAS40 and ASAS-PR responses at Week 48 was 76%, 55%, and 31%, respectively (figure 3A). A large proportion of patients achieved clinical remission according to ASDAS (ASDAS-ID) and reported major and clinically important improvements (figure 3B). In addition, there were improvements in other disease and patient-reported outcome measures, including BASFI, PtGADA, PhGADA, total spinal pain, ASQoL, ASAS HI, and fatigue (according to BASDAI) (table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean (A) ASDAS and (B) BASDAI up to Week 48. Safety Set (N=89). Observed data are shown. ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; AU, anterior uveitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Figure 3.

(A) ASAS20, ASAS40 and ASAS partial remission responder rates up to Week 48 in axSpA patients receiving CZP 200 mg Q2W and (B) ASDAS, CII, MI, and ID responder rates up to Week 48 in axSpA patients receiving CZP 200 mg Q2W. Safety Set (N=89). Observed data are shown; total number of patients assessed at each timepoint is shown. ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASAS20/40, ASAS 20%/40% response; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; CII, clinical important improvement; CZP, certolizumab pegol; ID, inactive disease; MI, major improvement; PR, partial remission; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Table 2.

Additional disease activity outcomes following 48 weeks of CZP 200 mg Q2W

| Disease activity measure | Week 0 (N=89) |

Week 48 (n=86) |

|---|---|---|

| ASDAS, mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.9) |

| ASDAS disease activity,* n (%) | ||

| Inactive disease | 0 (0) | 23 (27%) |

| Major improvement | – | 25 (29%) |

| Clinically important improvement | – | 53 (62%) |

| BASDAI, mean (SD) | 6.5 (1.5) | 3.3 (2.1) |

| Fatigue (BASDAI Q1), mean (SD) | 7.0 (1.8) | 4.0 (2.3) |

| BASFI, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.3) |

| Patient’s GADA, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.2) | 3.1 (2.4) |

| Physician’s GADA, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.3) |

| Total spinal pain, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.4) |

| ASQoL, mean (SD) | 10.6 (5.1) | 5.3 (4.8) |

| ASAS HI, mean (SD) | 9.3 (5.7) | 5.2 (3.8) |

Observed data are shown.

*ASDAS inactive disease: ASDAS <1.3; ASDAS major improvement: decrease of ≥2.0 units from baseline; ASDAS clinically important improvement: decrease of ≥1.1 units from baseline.

ASAS HI, Assessment of Axial Spondyloarthritis international Society Health Index; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; CZP, certolizumab pegol; GADA, Global Assessment of Disease Activity; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Safety

During the treatment period, 58 patients experienced 190 adverse events (table 3). Of these, five patients experienced nine events classed as serious by the investigator. These included two events of uveitis in a single patient; these events were classified as serious as the patient was hospitalised for further diagnosis and treatment in accordance with local treatment guidelines. Furthermore, there was one case each of vestibular disorder, incarcerated hernia, sarcoidosis, tenosynovitis, hemangioma, prostate cancer, and pregnancy (recorded as serious due to elective termination). Of the serious adverse events, three were considered by the investigator to be related to CZP (both cases of uveitis and the one case of sarcoidosis). There were no deaths or serious cardiovascular events during the study.

Table 3.

Safety outcomes

| MedDRA 19.0 Term n (%) [#] | CZP 200 mg Q2 W (N=89) |

|---|---|

| Any AE | 58 (65.2) [190] |

| Infections and infestations | 27 (30.3) [53] |

| Latent tuberculosis | 1 (1.1) [1] |

| Serious AEs* | 5 (5.6) [9] |

| Discontinuation of CZP due to AEs | 4 (4.5) [6] |

| Drug-related AEs | 14 (15.7) [37] |

| Severe AEs | 3 (3.4) [4] |

| Deaths | 0 |

Adverse events are reported using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 19.0.

*Serious AEs (recorded as such by the investigator) include vestibular disorder, two cases of uveitis, incarcerated hernia, sarcoidosis, tenosynovitis, hemangioma, prostate cancer, and pregnancy.

#, number of occurrences; AE, adverse event; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, C-VIEW is the first clinical trial to prospectively focus on the impact of CZP on the incidence of AAU flares in HLA-B27 positive patients with active axSpA and a recent history of recurrent AAU, encompassing patients with both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA. During the first 48 weeks of CZP treatment, there was a significant reduction in the number of AAU flares per person and an 87% reduction in the overall AAU flare rate per 100 PY, compared to the 48 weeks before CZP. It is important to note that these axSpA patients had a higher risk of recurrence of AAU because they had already experienced an attack of AAU, compared with an axSpA population who not yet had an attack of AAU.25 The flare rate during treatment for patients with more severe AAU (>1 flare in the 48 weeks pre-baseline) was similar to that for patients who had ≤1 flare (23.5 vs 16.5 per 100 PY, respectively), further demonstrating the impact of CZP on recurrent AAU in patients with axSpA.

To date, only a small number of studies have reported on the influence of CZP on AAU, of which two had a retrospective design.32–35 Two prospective studies reported secondary or post hoc analyses of the AAU flare incidence for CZP-treated axSpA patients, both with and without a history of uveitis, who participated in the phase 3, placebo-controlled RAPID-axSpA trial.34 35 In this trial, in the subgroup that was randomised to CZP and had a previous history of AAU, the AAU incidence rate after 24 weeks’ CZP was comparable to the present study (17.1 per 100 PY vs 18.7 per 100 PY after 48 weeks in this study),34 and was maintained up to 204 weeks (15.2 per 100 PY).35 In comparison, the AAU incidence rate after 24 weeks in the patients with a history of AAU randomised to placebo in the RAPID-axSpA study was 38.5 per 100 PY.34 Patients from RAPID-axSpA who had a history of AAU did not necessarily have a recent history of AAU and were therefore considered to have a lower risk of an AAU flare than patients with a recent attack, as in the current study.25 It is important to note that although patients in the current study were expected to be at a higher risk, the flare risk in both studies was comparable. Similar to the current study, the RAPID-axSpA population included patients across the full axSpA spectrum; however, the AAU incidence in the year before CZP treatment was not reported for these patients. The rate of AAU in the C-axSpAnd trial of CZP in nr-axSpA (including 317 patients of whom 16% had a history of AAU) was also lower in the CZP group compared to patients receiving placebo over 52 weeks (2.5 vs 7.2 per 100 PY, respectively).37

Prospective studies of other TNFi monoclonal antibodies in patients with r-axSpA have demonstrated reductions in the AAU flare incidence during treatment similar to the present study; however, differences in study design make it difficult to make comparisons.23 24 The 12-month GO-EASY study of golimumab showed that the AAU incidence rate decreased by 80% (11.1 to 2.2 per 100 PY) in r-axSpA patients both with and without a history of AAU.23 An 85% reduction (200 to 31 per 100 PY) was reported by van Denderen et al following 12 months adalimumab in 26 patients with a recent history of AAU.24 Additionally, Rudwaleit et al reported a 68% (176.9 to 56.0 per 100 PY) reduction following 20 weeks’ adalimumab treatment in 106 patients with r-axSpA who had an AAU flare in the year preceding treatment.25

The findings of the present study provide additional evidence supporting the influence of CZP on prevention of AAU flares in patients with axSpA. In line with these reports, they support the use of CZP as a treatment for patients with axSpA and recurrent AAU. This is the first trial to prospectively show the treatment benefit of CZP on AAU flares in HLA-B27 positive patients with r- and nr-axSpA. This is important, given the paucity of data on patients with nr-axSpA affected by AAU, and the fact that AAU is a prevalent extra-articular manifestation in both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA patient populations.38 Moreover, this study shows that CZP is effective in a patient population at a relatively increased risk for AAU flares (due to a recent history of recurrent AAU and HLA-B27 positivity). Although we studied a high-risk population, the AAU incidence was comparable to the AAU incidence in the general axSpA population during CZP treatment.34 The prospective nature of the study also enabled for objective evaluation of the AAU flare incidence in these patients; in previous studies, analysis of AAU flares during treatment has mostly been retrospective.25 32–34

Regarding the impact of CZP on axSpA disease activity, the improvements in axSpA observed in this study were comparable with data from previous clinical trials.35 37 In keeping with data from these previous trials, no new safety signal was identified. However, it is noteworthy that a single patient experienced two AAU flares during the CZP treatment period which were classed as treatment-related serious adverse events by the local investigator because the patient could not be treated at the outpatient clinic due to local guidelines. It is not clear whether these events were true adverse reactions induced by TNFi therapy (as previously reported)30 39 or were simply severe uveitis flares despite treatment with CZP. During the 48-week CZP treatment period, only four patients (4%) discontinued the study, indicating that CZP is well tolerated.

A potential limitation of this study is the lack of a comparator arm (eg, placebo or other agent) in the study design. However, assigning patients to placebo was considered to be unethical since all patients in the study had high axSpA disease activity requiring treatment. Since only HLA-B27-positive patients were included (who generally have more frequent, and more severe AAU recurrences), it is unclear to what extent our results are applicable to HLA-B27-negative patients. A caveat of conducting within-patient comparisons is that it may lead to statistical artefacts such as regression to the mean, as it is unlikely that all patients who had experienced a recent flare would experience another flare in the following year. However, patients with a recent history of two or more AAU flares are thought to have a significantly higher risk of new AAU flares,40 and the fact that the AAU incidence strongly decreased during CZP in this high-risk patient population, and was in accordance with the AAU risk during CZP in non-high-risk populations, is an important finding.23 24 34 41 In addition, the entire study period of 2 years will further serve to counterbalance a potential regression to the mean effect.

There are some patients with AAU in whom TNFi therapies are not effective or who develop a diminished response over time.42 However, since this study included only four patients with prior TNFi (etanercept) exposure, this could not be explored further. It is a possibility that prior biologic treatment may have reduced the post-baseline risk of a recurrence in these patients, although these patients would also potentially have had fewer AAU flares pre-baseline. Finally, a total of 20 patients used systemic corticosteroids in the pretreatment and/or treatment periods, but only two patients were still exposed at baseline, which could have been a contributing factor to the prevention of AAU flares for some time in these patients.

In summary, this is the first study to prospectively examine the impact of CZP on the incidence of AAU flares in HLA-B27-positive patients with active axSpA, including r-axSpA and nr-axSpA, and a recent history of recurrent AAU. During CZP treatment, there was a significant reduction in the number of AAU flares, while the efficacy and safety of CZP in the axSpA population were comparable to previous trials.35 37 Overall, the results from this 48-week interim analysis indicate that CZP is a suitable treatment option for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, the investigators and their teams who took part in this study. The authors also acknowledge Simone E Auteri, PhD MSc EMS, UCB Pharma, Belgium, for publication coordination and critical review, Jeffrey Stark and Victor Sloan, UCB Pharma, USA, for critical review and Madeleine Warner, PhD, and Jessica Patel, PhD, from Costello Medical, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. This study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Footnotes

Contributors: IvdHB, FDV, TR, BH, OIS, BVL, LB, and MR have substantially contributed to study conception and design; IvdHB, RvB, FDV, TR, JTR, MMS, BH, OIS, LB, and MR have substantially contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data; IvdHB, RvB, FDV, TR, JTR, MMS, BH, OIS, BVL, LB, MR were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version of the article to be published.

Funding: This study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Competing interests: Yes, there are competing interests for one or more authors and I have provided a Competing Interests statement in my manuscript.

Disclosures: IvdHB: Honoraria/consulting fees/research grants from AbbVie, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; RVB: none; FDV: Honoraria/consulting fees/research grants from Bayer, Novartis, IDxDR, UCB Pharma; TR: Honoraria/consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Chugai, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma; JTR: Consultancy fees from UCB Pharma, AbbVie, Celldex, Gilead, Novartis, Janssen, Santen, Roche, Eyevensys, Corvus, Horizon; royalties from UpToDate; clinical trial support from Pfizer; MMS: none; BH, OIS, BVL, LB: Employees of UCB Pharma; MR: Honoraria/consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Data sharing statement: Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers six months after product approval in the US and/or Europe, or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymised individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents which may include: analysis-ready data sets, study protocol, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications, and clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, et al. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:65–73 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. a proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8 10.1002/(ISSN)1529-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baraliakos X, Braun J. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: what are the similarities and differences? RMD Open 2015;1:e000053 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heijde D, et al. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:196. 10.1186/s13075-016-1093-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:717–27 10.1002/art.v60:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gritz DC, Wong IG, Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California epidemiology of uveitis study. Ophthalmology 2004;111:491–500. discussion 500 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewerton DA, Caffrey M, Nicholls A, et al. Acute anterior uveitis and HL-A 27. Lancet 1973;302:994–6 10.1016/S0140-6736(73)91090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewerton DA. The genetics of acute anterior uveitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 1985;104:248–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power WJ, Rodriguez A, Pedroza-Seres M, et al. Outcomes in anterior uveitis associated with the HLA-B27 haplotype. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1646–51 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan MA, Haroon M, Rosenbaum JT. Acute anterior uveitis and spondyloarthritis: more than meets the eye. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015;17:59. 10.1007/s11926-015-0536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essers I, Ramiro S, Stolwijk C, et al. Characteristics associated with the presence and development of extra-articular manifestations in ankylosing spondylitis: 12-year results from OASIS. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:633–40 10.1093/rheumatology/keu388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Essers I, van Tubergen A, et al. The epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based matched cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1373–8 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeboulon N, Dougados M, Gossec L. Prevalence and characteristics of uveitis in the spondyloarthropathies: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:955–9 10.1136/ard.2007.075754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacchiega ABS, Balbi GGM, Ochtrop MLG, et al. Ocular involvement in patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:2060–7 10.1093/rheumatology/kex057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Rourke M, Haroon M, Alfarasy S, et al. The effect of anterior uveitis and previously undiagnosed spondyloarthritis: results from the duet cohort. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1347–54 10.3899/jrheum.170115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCluskey PJ, Towler HM, Lightman S. Management of chronic uveitis. BMJ 2000;320:555–8 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Update on the use of systemic biologic agents in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Biologics: Targets Therapy 2014;8:67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sangwan VS. Treatment of uveitis: beyond steroids. Indian J Ophthalmol 2010;58:1–2 10.4103/0301-4738.58466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, Garcia-Sanchez J, Iradier T, et al. Sulfasalazine in the prevention of anterior uveitis associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Eye (Lond) 2000;14:340–3 10.1038/eye.2000.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz-Fernandez S, Garcia-Aparicio AM, Hidalgo MV, et al. Methotrexate: an option for preventing the recurrence of acute anterior uveitis. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1130–3 10.1038/eye.2008.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz-Fernandez S, Hidalgo V, Fernandez-Melon J, et al. Sulfasalazine reduces the number of flares of acute anterior uveitis over a one-year period. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Bentum RE, Heslinga SC, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Reduced occurrence ate of acute anterior uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis treated with golimumab: the go-easy study. J Rheumatol 2018 10.3899/jrheum.180312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Denderen JC, Visman IM, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Adalimumab significantly reduces the recurrence rate of anterior uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1843–8 10.3899/jrheum.131289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudwaleit M, Rødevand E, Holck P, et al. Adalimumab effectively reduces the rate of anterior uveitis flares in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a prospective open-label study. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;68:696–701 10.1136/ard.2008.092585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Listing J, et al. Decreased incidence of anterior uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with the anti-tumor necrosis factor agents infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galor A, Perez VL, Hammel JP, et al. Differential effectiveness of etanercept and infliximab in the treatment of ocular inflammation. Ophthalmology 2006;113:2317–23 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saurenmann RK, Levin AV, Rose JB, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors in the treatment of childhood uveitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:982–9 10.1093/rheumatology/kel030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lie E, Lindstrom U, Zverkova-Sandstrom T, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor treatment and occurrence of anterior uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Swedish biologics register. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1515–21 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim LL, Fraunfelder FW, Rosenbaum JT. Do tumor necrosis factor inhibitors cause uveitis? A registry-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raffeiner B, Ometto F, Bernardi L, et al. Inefficacy or paradoxical effect? Uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept. Case Rep Med 2014;2014:471319 10.1155/2014/471319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tosi GM, Sota J, Vitale A, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol and golimumab in the treatment of non-infectious uveitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:680–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabiani C, Vitale A, Rigante D, et al. Efficacy of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibodies in patients with non-infectious anterior uveitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudwaleit M, Rosenbaum JT, Landewé R, et al. Observed incidence of uveitis following certolizumab pegol treatment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:838–44 10.1002/acr.22848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Landewé R, et al. Sustained efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes of certolizumab pegol in axial spondyloarthritis: 4-year outcomes from RAPID-axSpA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:1498–509 10.1093/rheumatology/kex174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Kay J, et al. A fifty-two-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1101–11 10.1002/art.2019.71.issue-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallis D, Haroon N, Ayearst R, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: part of a common spectrum or distinct diseases? J Rheumatol 2013;40:2038–41 10.3899/jrheum.130588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wendling D, Paccou J, Berthelot J-M, et al. New onset of uveitis during anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment for rheumatic diseases. Seminars Arthritis Rheumatism 2011;41:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Natkunarajah M, Kaptoge S, Edelsten C. Risks of relapse in patients with acute anterior uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:330–4 10.1136/bjo.2005.083725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grunwald L, Newcomb CW, Daniel E, et al. Risk of relapse in primary acute anterior uveitis. Ophthalmology 2011;118:1911–15 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cordero-Coma M, Sobrin L. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy in uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol 2015;60:575–89 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2019-001161s001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)