Abstract

Objectives

A few studies on antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) treatments have shown the therapeutic efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). However, the therapeutic efficacy of MMF compared with that of cyclophosphamide (CYC) in patients with AAV has not been established. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of MMF as a remission induction therapy in patients with AAV comparing it with the efficacy of CYC.

Methods

We searched randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the efficacy of MMF with that of CYC in patients with AAV on three different websites: PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar. We compared the difference in the relative risk (RR) of each outcome based on a Mantel-Haenszel random-effects model.

Results

We analysed data from four RCTs with 300 patients for the study. The 6-month remission rate (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.38, p=0.48), the 6-month ANCA negativity (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.90, p=0.15) and the long-term relapse rate (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.31, p=0.26) were all similar between the two treatments. The rates of death, infection and leucopenia were also similar between the two groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.74, p=0.93; RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.01, p=0.33; RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.32, p=0.15, respectively).

Conclusions

We found no difference between the therapeutic efficacy of MMF and that of CYC in patients with AAV. MMF may be an alternative remission induction therapy in patients with non-life-threatening AAV.

Keywords: ANCA-associated vasculitis, meta-analysis, randomised control trials, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide

INTRODUCTION

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterised by multiorgan involvement affecting the ears, nose, throat (ENT), lungs, kidneys and peripheral nerves that may lead to loss of an organ or even death. The efficacy of intensive immunosuppressive therapy with agents such as cyclophosphamide (CYC) or rituximab (RTX) has been established as a remission-inducing therapy in patients with organ/life-threatening AAV1–5 and is recommended as a conventional therapy.6 However, we sometimes hesitate to use CYC in elderly individuals, women of childbearing age or individuals with renal insufficiency in clinical practice because of its cytotoxicity and possible adverse effects (infection, leucopenia and infertility). In the CYCLOPS Study, the rate of adverse events was relatively high (the percentages of leucocytopenia and infections in patients after intravenous CYC treatment were both 26% and those after oral CYC treatment were 45% and 29%, respectively).3 RTX is a complementary drug, but it induces long-lasting depletion of B cells and hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with AAV,7 which may contribute to infections that could become fatal (the severe infection rate was 15%, and 5% of deaths were due to them).8 Therefore, less toxic remission induction therapies are required.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

The therapeutic efficacy of MMF compared with that of CYC in patients with AAV has not been established.

What does this study add?

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of MMF as a remission induction therapy in patients with AAV comparing it with the efficacy of CYC.

We found no difference between the therapeutic efficacy of MMF and that of CYC on patients with AAV.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

MMF may be an alternative remission induction drug for non-life-threatening AAV.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a prodrug of mycophenolic acid, and it inhibits inosine-50-monophosphate dehydrogenase. MMF depletes guanosine nucleotides preferentially in T and B lymphocytes, inhibiting their proliferation and thereby suppressing cell-mediated immune responses and antibody formation.9 MMF has been used since the 1990s as an immunosuppressive drug to treat patients after kidney transplantation10 and more recently to treat connective tissue diseases. MMF (as well as CYC) is recommended as a first-line therapy for lupus nephritis,11 because studies have shown by meta-analysis that it has equivalent or better efficacy, and less side effects (such as amenorrhea) than CYC.12 13

Some studies have reported the therapeutic efficacy of MMF for the treatment of AAV.14–17 However, the therapeutic efficacy of MMF compared with that of CYC in patients with AAV has not been established. Some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have compared the therapeutic efficacy of MMF with that of CYC in patients with AAV; we systematically reviewed them and performed a meta-analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient and public involvement statement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Search strategy

We searched the databases at PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for RCTs comparing the therapeutic efficacy of MMF with that of CYC in patients with AAV. On PubMed and Cochrane Library, we used the terms ‘ANCA’ or ‘antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody’ or ‘MPA’ or ‘microscopic polyangiitis’ or ‘GPA’ or ‘granulomatosis with polyangiitis’ or ‘Wegener’s granulomatosis’ and ‘MMF’ or ‘mycophenolate mofetil’ and ‘CYC’ or ‘cyclophosphamide’. On Google Scholar, we used the terms ‘ANCA-associated vasculitis’, ‘mycophenolate mofetil’, ‘cyclophosphamide’, ‘randomised’, ‘–rituximab’ and ‘–TNF’. We imposed no language restrictions, but excluded data available only in abstracts or unpublished studies. The searches were performed three times to identify articles published between 1 January 1990 and 1 September 2019. Final searches were performed on 15 September 2019. We followed the guidelines in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.18

Study selection

We included original articles (excluding reviews), RCTs comparing the therapeutic efficacies between MMF and CYC, titles or abstracts containing keywords used in search engines and patients with AAV diagnosed according to definitions from the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference.19 20 We excluded studies that provided no data on the 6-month remission rates. We ensured that studies published by the same author(s) did not have duplicate patients.

Validity and quality assessment

Two authors (KK and TM) independently checked and selected all the references. We assessed the risk of bias according to RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing the risk of bias to randomised trials.21 We also assessed the symmetry of funnel plots for publication bias.22

Data extraction

We extracted data from all the studies in our systematic review, including authors, year of publication, number of patients, age, gender, myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA positivity, proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA positivity, serum creatine levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS), and organ involvement. Additionally, we extracted data on outcomes of patients with remission (BVAS=0) and ANCA negativity at 6 months, relapses, infections, malignancy, leucopenia, deaths and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) during the observation period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of MMF in AAV.

Data synthesis

We performed a meta-analysis to compare the therapeutic efficacy of MMF with that of CYC in patients with AAV. We expressed the outcomes as relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs. We calculated summarised data for the meta-analysis using a random-effects model (REM) owing to the therapeutic protocol differences among the studies (DerSimonian and Laird method).23 We set the statistical significance at p<0.05 and calculated the I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity across studies, defining I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% as low, moderate and high, respectively.24 We performed a meta-regression analysis to assess the correlation between the RRs of 6-month remission rates and MPO-ANCA positivity because the intra-study heterogeneity was relatively high (I2=60%) according to the REM results. We conducted all analyses using R version 3.6.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) and EZR version 1.40.25

RESULTS

Study characteristics

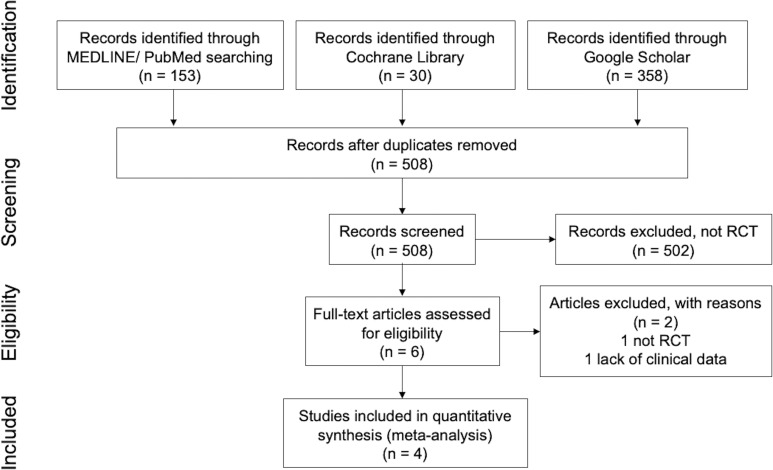

We collected a total of 541 articles from 3 websites (153 articles from PubMed, 30 articles from Cochrane Library and 358 articles from Google Scholar). After the removal of duplicates or triplicates, 508 articles were identified. After screening by title and abstract, we excluded 502 more articles because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. We assessed the full texts of the remaining six articles for eligibility and excluded two articles because one was not an RCT and the other did not include detailed clinical data. Finally, we used four studies for our analysis (figure 1).26–29

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

We extracted key clinical data and summarised them in table 1. Two studies26 27 were conducted in European countries and the others28 29 in China. Patients were diagnosed as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) according to definitions from the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference.19 20 The initial condition of the patients in the selected studies was as follows: newly diagnosed disease,27 29 relapsing disease26 and relatively early onset (the mean of disease duration was approximately 6 months).28 Observational period was 6 months, 28 29 18 months27 and 4 years26 after initial treatment. Treatment regimens of corticosteroids were the following: described as ‘prednisolone in a tapering regimen’,26 prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day initially and reduced to 5 mg/day at the end of 6 months after the initial treatment27 and oral prednisone 0.6–0.8 mg/kg/day followed by initial intravenous methylprednisolone pulse (0.5 g) and gradually tapering.28 29 Doses of MMF were 1.0 g/day26 and 2.0 g/day.27–29 CYC was introduced by oral intake26 and intravenous pulse.27–29 Remission was defined as BVAS=0 in all the studies. Patients with life-threatening diseases such as alveolar bleeding, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and ESRD were excluded in all the selected studies, according to their own exclusion criteria. Therefore, we could not evaluate the efficacy of MMF for patients with life-threatening AAV compared with CYC in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Date | Follow-up period | Patients | Intervention (MMF) | Intervention (CYC) | Definition of remission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuin J et al26 | 2019 | 4 years | MPA or GPA, relapse | 2 g/day | Oral CYC 2 mg/kg/day | BVAS=0 and CRP<10 mg/dL at 6 months |

| Jones RB et al27 | 2019 | 18 months | MPA or GPA, new diagnosis | 2 g/day (dose up to 3 g/day permitted) | Intravenous pulsed CYC 15 mg/kg every 2–3 weeks | BVAS=0 at 2 occasions apart within 6 months |

| Han F et al28 | 2011 | 6 months | MPA | 1.0 g/day (1.5 g/day if BW>70 kg) | Intravenous pulse CYC, 1.0 g/body monthly | BVAS=0 with PSL<7.5 mg/day at 6 months |

| Hu W et al29 | 2008 | 6 months | MPA or GPA, new diagnosis | 2.0 g/day (1.5 g/day if BW<50 kg) | Intravenous pulse CYC, 0.75–1.0 g/m2 body surface area monthly | BVAS=0 at 6 months |

BVAS, Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; CYC, cyclophosphamide; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; PSL, prednisolone.

Table 2 shows the baseline (at the beginning of the observation) data of the patients in each study. The age of patients was 49–61 years.27–29 The proportion of males was 39%–68%.27–29 The positive rate of MPO-ANCA was 11%–100%,27–29 whereas that of PR3-ANCA was 0%–89%.26–29 The levels of C reactive protein (CRP) were 19–36 mg/L.26–28 The levels of eGFR were 34–60 mL/min/1.73 m2.26–28 BVAS values were 15–19.26 29 Renal organ involvement was observed in 75%–100% of the patients.26–29 Lung organ involvement was observed in 46%–61% of the patients.26–28 The ENT involvements were observed in 48%–59% of the patients.26 27 We evaluated publication bias using a funnel plot (Supplemental Figure 1), which indicated that all the studies were symmetrically located. The risks of bias for the 6-month remission rates were low in three studies and somewhat concerning in one study (Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 2.

Baseline data of each study

| Study | Patients (N) | Age | Sex (male, %) | MPO-ANCA | PR3-ANCA | Scre (mg/dL) | eGFR (mL/min/ | BVAS | Organ involvement (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | 1.73 m2) | Renal | Lung | ||||||

| Tuin J et al26 | 84 | 60 | 68 | 10.7 | 89.3 | 1.2* | 57.5/60 | 15* | 75 | 50 |

| (MMF/CYC) | ||||||||||

| Jones RB et al27 | 140 | 60*/61* | 53 | 38.6* | 59.1* | NA | 51 | 19/18 | 81.4 | 46.4 |

| (MMF/CYC) | (MMF/CYC) | |||||||||

| Han F et al28 | 41 | 56 | 39 | 100 | 0 | 3.53 | 34.4 | 17.7 | 100 | 61 |

| Hu W et al29 | 35 | 49.1 | 43 | 80 | 2.9 | 3.56 | NA | 15.3 | 100 | NA |

Continuous variables are listed as means, except*, which are listed as medians.

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; BVAS, Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; CYC, cyclophosphamide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NA, not available; PR3, proteinase 3; Scre, serum creatine.

rmdopen-2020-001195s001.pdf (240.5KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001195s002.pdf (130.8KB, pdf)

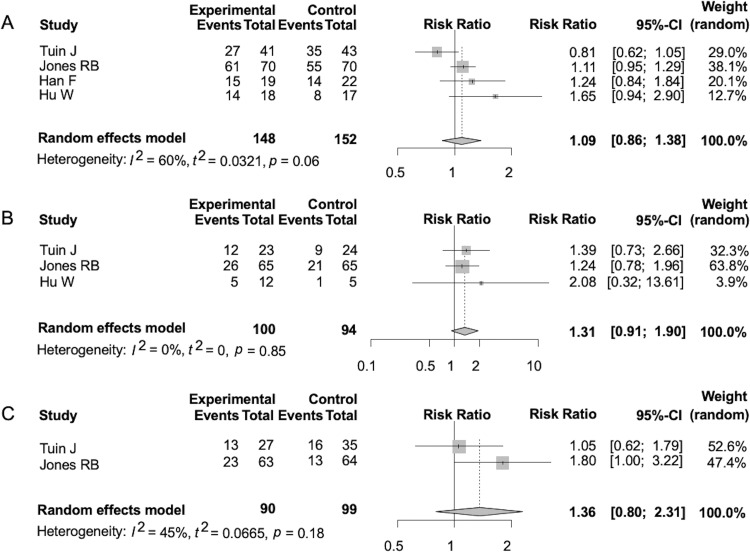

Assessment on efficacy of MMF

The 6-month remission rates were similar between patients treated with MMF and those treated with CYC (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.38, p=0.48) (figure 2A). The 6-month ANCA negativities were also similar between the two groups (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.90, p=0.15) (figure 2B). Further, the relapse rates during the observation period were similar between the two groups (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.31, p=0.26) (figure 2C). The heterogeneities for each of the former analyses (as assessed by the I2 statistic) were 60% (p=0.06), 0% (p=0.85) and 45% (p=0.18), respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of relative risk about the following outcomes. Remission rate at 6 months (A), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody negativity at 6 months (B) and relapse rate (C).

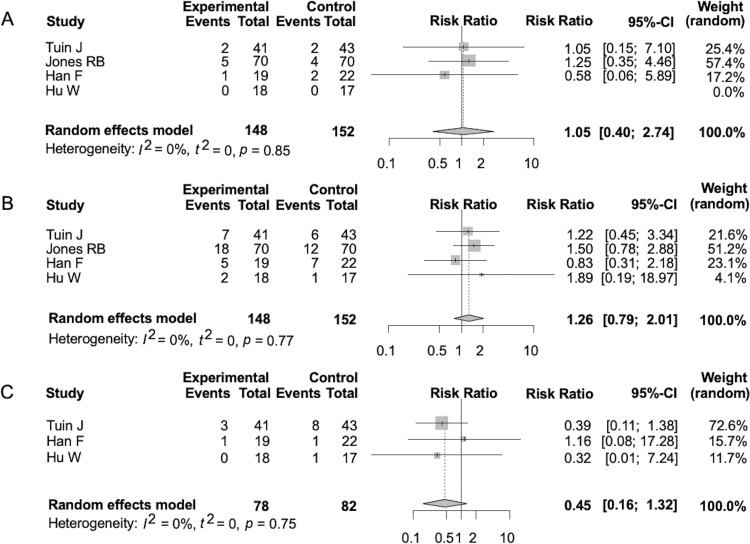

Assessment of MMF safety

The mortality rates were similar between the two groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.74, p=0.93) (figure 3A). The infection rates during the observation period were similar between the two groups (RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.01, p=0.33) (figure 3B). The rates of leucopenia during the observation period were similar between the two groups (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.32, p=0.15) (figure 3C). The rates of ESRD at the end of the observation period were similar between the two groups (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.79, p=0.57) (Supplemental Figure 3A). The rates of patients developing malignancies during the observation period were similar between the two groups (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.27 to 3.98, p=0.96) (Supplemental Figure 3B). The rates of severe infection or death due to infection were similar between the two groups (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.50, p=0.80) (Supplemental Figure 3C). The heterogeneities for each of the above analyses according to the I2 statistic were all 0% (p=0.85, p=0.77, p=0.75, p=0.52, p=0.98, and p=0.61, respectively).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of relative risk about the following outcomes. Death rate (A), infection (B) and leucocytopenia (C). See figure 2 for definitions.

rmdopen-2020-001195s003.pdf (156.5KB, pdf)

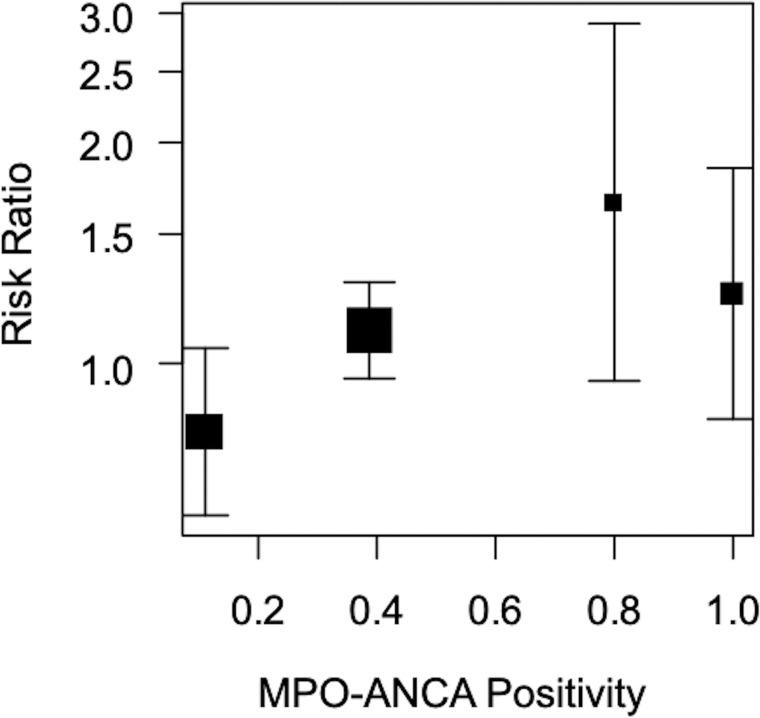

Intrastudy heterogeneity assessment

Our meta-regression analysis indicated a positive correlation between the RRs of 6-month remission rates and MPO-ANCA positivity (p=0.026) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Meta-regression analysis where the objective variable is the relative risk of remission rate at 6 months and the explanatory variable is MPO-ANCA positivity.

DISCUSSION

We found similar 6-month remission rates for patients treated with MMF and those treated with CYC. However, the heterogeneities among the studies were relatively large (I2=60%). The background patient variables (age, gender, BVAS and organ manifestations) were similar between the study groups. On the other hand, the ANCA positivity rates were heterogeneous among studies (table 2). These results are not surprising, because the ANCA profiles in patients with AAV differ between those in Western and Asian countries (PR3-ANCA positivity is more common in Western countries and MPO-ANCA positivity in Asian ones).30 Two of the studies analysed here were conducted in European countries and the others in China. Patients with PR3-ANCA-positive AAV are more likely to relapse than patients with MPO-ANCA-positive AAV.27 31 Therefore, we speculate that the treatment efficacy of MMF in patients with AAV may depend on their ANCA subtype. Our meta-regression analysis indicated a positive correlation between the RRs of 6-month remission rates and MPO-ANCA positivity (figure 4). This suggests that patients with MPO-ANCA-positive AAV are more likely to respond well to MMF than patients with PR3-ANCA-positive AAV.

The 6-month ANCA negativity, which has been reported as a predictor of remission,32 and the relapse rates after several months were similar between the groups treated with MMF and those treated with CYC. However, in a report by Jones et al, the relapse rate was significantly higher in the MMF treatment group than in the CYC group.27 We speculate that both factors of patients and treatment drug may be related to this result. Regarding the factor of patients, PR3-ANCA-positive AAV was dominant (59.1%) in their cohort. The result of meta-regression analysis in our study suggests that patients with PR3-ANCA-positive AAV are less likely to respond to treatment with MMF compared with CYC. Regarding the factor of treatment drug, CYC is an alkylating drug that cross-links DNA strands to inhibit cell division and cause cell death, whereas MMF is an antimetabolite drug that inhibits the synthesis of guanine nucleotide and suppresses the proliferation of lymphocytes. These differences of pharmacokinetics may lead to less pronounced immunosuppressive effect by MMF compared with CYC. From the above, we should not use MMF to GPA or patients with PR-3 ANCA-positive AAV enthusiastically.

The death rates in patients with AAV were similar between the treatment groups. Infections were the dominant causes of death in this study; 5 out of 7 patients (71%) in the treatment group with MMF and 3 out of 8 (38%) in the treatment group with CYC died of infections. Likewise, infections have been reported as major causes of death (50%) in patients with AAV.33 The rates of overall and severe infections were similar between the treatment groups. This tendency was also observed in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) treated with either MMF or CYC.13 The rates of leucopenia were similar between the treatment groups. Both neutropenia and lymphopenia are known risk factors for infection.34 Therefore, the leucopenia caused by MMF may influence the risk of infection in patients with AAV. On the basis of these results, patients with AAV treated with MMF or CYC should be monitored for infections. However, our results do not lead to the conclusion that the side effects of MMF and CYC are equivalent in every respect, because treatment with CYC has some major problems such as carcinogenesis. In our results, the risks of malignancy were similar between the treatment groups (Supplemental figure 3B). CYC treatment increases the rates of bladder cancer, leukaemia, lymphoma and skin malignancies in a dose/duration-dependent manner, and MMF treatment produces a lower risk of malignancy than other immunosuppressants.35 The risk of carcinogenesis in patients with AAV treated with MMF should be evaluated during long observation periods and large cohorts in the future.

Although amenorrhea and infertility are important outcomes, especially for women of childbearing age, we were not able to assess them in our meta-analysis. CYC treatment has been reported to diminish the ovarian reserve in women with GPA.36 Another meta-analysis showed that the use of MMF is related to a significant reduction in the risk of amenorrhea compared with the use of CYC in patients with lupus nephritis.12 Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels, which are sensitive ovarian damage markers, were not decreased in patients with lupus nephritis treated with MMF compared with those in the control population.37 Although AAV is less likely to occur in young women than SLE, permanent infertility should be a cause for concern when considering CYC treatment for young women with AAV. In such cases, MMF may be an attractive remission-inducing drug alternative.

For remission induction therapy in life-threatening AAV, we should initially use RTX as a complementary drug to CYC because RTX has been shown to have efficacy equivalent to CYC in severe AAV.4 5 Conversely, in case of non-life-threatening AAV, there is concern about serious infection caused by treatment with RTX, considering the relatively high rate of severe infectious events in a previous study.8 Therefore, MMF may be considered as a complementary drug to CYC for patients with non-life-threatening AAV, before the introduction of RTX.

Our study has the following limitations: (i) publication bias may have influenced our results because of the small number of studies and patients in our analysis; (ii) the assessments on MMF long-term efficacy and safety were insufficient because of the short observation periods and (iii) we did not elucidate the efficacy and safety of MMF for patients with life-threatening diseases such as alveolar bleeding because they were excluded in all the studies we synthesised. In addition, MMF doses of the treatment protocols differed among studies (table 1). The dose of MMF taken orally does not directly reflect the blood concentration of mycophenolic acid, because its pharmacokinetics are complicated by factors such as renal function, serum albumin concentration, drug interactions and genotype of the enzyme that metabolises it to an inactive compound.38 However, high blood concentrations of mycophenolic acid have been associated with stable disease in patients with AAV treated with MMF.39 Therefore, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that our outcomes were influenced by the heterogeneity of blood concentrations of mycophenolic acid. In the study by Tuin et al,26 CYC was taken orally, whereas it was administered intravenously in the other studies.27–29 We believe this difference should not influence the result of the 6-month remission rate, because the CYCLOPS Study showed that the remission rates of oral CYC and intravenous CYC were similar.3

In conclusion, we found no differences between the therapeutic efficacies of MMF and CYC on patients with AAV. MMF is recommended for patients with certain characteristics (MPO-ANCA-positive AAV, non-life-threatening state and valid reasons to avoid using the conventional drug). MMF may be an alternative remission induction drug for non-life-threatening AAV.

Footnotes

Contributors: KK, TM and AK authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. TM had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Study conception and design: KK and TM. Acquisition of data: KK and TM. Analysis and interpretation of data: KK, TM and AK.

Funding: The authors declare no financial support or other benefits from commercial sources for the work reported on in the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Data sharing statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Novack SN, Pearson CM. Cyclophosphamide therapy in Wegener’s granulomatosis. N Engl J Med 1971;284:938–42. 10.1056/NEJM197104292841703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauci AS, Wolff SM. Wegener’s granulomatosis: studies in eighteen patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1973;52:535–61. 10.1097/00005792-197311000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DR, et al. . Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:670–80. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. . Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:221–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. . Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:211–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yates M, Watts RA, Bajema IM, et al. . EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1583–94. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venhoff N, Niessen L, Kreuzaler M, et al. . Reconstitution of the peripheral B lymphocyte compartment in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitides treated with rituximab for relapsing or refractory disease. Autoimmunity 2014;47:401–8. 10.3109/08916934.2014.914174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charles P, Neel A, Tieulie N, et al. . Rituximab for induction and maintenance treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitides: a multicentre retrospective study on 80 patients. Rheumatology 2014;53:532–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison A. Mechanisms of action of mycophenolate mofetil. Lupus 2005;14:2–8. 10.1177/096120330501400102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulton B, Markham A. Mycophenolate mofetil. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy in renal transplantation. Drugs 1996;51:278–98. 10.2165/00003495-199651020-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al. . 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:736–45. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh M, James M, Jayne D, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil for induction therapy of lupus nephritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:968–5. 10.2215/CJN.01200307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Touma Z, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil for induction treatment of lupus nephritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:69–78. 10.3899/jrheum.100130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joy MS, Hogan SL, Jennette JC, et al. . A pilot study using mycophenolate mofetil in relapsing or resistant ANCA small vessel vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:2725–32. 10.1093/ndt/gfi117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koukoulaki M, Jayne DR. Mycophenolate mofetil in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated systemic vasculitis. Nephron Clin Pract 2006;102:100–7. 10.1159/000089667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stassen PM, Tervaert JW, Stegeman CA. Induction of remission in active anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis with mycophenolate mofetil in patients who cannot be treated with cyclophosphamide. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:798–802. 10.1136/ard.2006.060301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva F, Specks U, Kalra S, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil for induction and maintenance of remission in microscopic polyangiitis with mild to moderate renal involvement: a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:445–53. 10.2215/CJN.06010809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. . Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:187–92. 10.1002/art.1780370206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. . 2012 Revised international Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1–11. 10.1002/art.37715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. . RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:105–14. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl 2013;48:452–8. 10.1038/bmt.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuin J, Stassen PM, Bogdan DI, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for the induction of remission in nonlife-threatening relapses of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:1021–8. 10.2215/CJN.11801018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones RB, Hiemstra TF, Ballarin J, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for remission induction in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:399–405. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han F, Liu G, Zhang X, et al. . Effects of mycophenolate mofetil combined with corticosteroids for induction therapy of microscopic polyangiitis. Am J Nephrol 2011;33:185–92. 10.1159/000324364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W, Liu C, Xie H, et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil versus statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl 2013;48:452–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott DGI, Watts RA. Epidemiology and clinical features of systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013;17:607–10. 10.1007/s10157-013-0830-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lionaki S, Blyth ER, Hogan SL, et al. . Classification of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody vasculitides: the role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody specificity for myeloperoxidase or proteinase 3 in disease recognition and prognosis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3452–62. 10.1002/art.34562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan MD, Szeto M, Walsh M, et al. . Negative anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody at switch to maintenance therapy is associated with a reduced risk of relapse. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:129 10.1186/s13075-017-1321-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kempen JH, Gangaputra S, Daniel E, et al. . Long-term risk of malignancy among patients treated with immunosuppressive agents for ocular inflammation: a critical assessment of the evidence. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146:802–12. 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clowse ME, Copland SC, Hsieh TC, et al. . Ovarian reserve diminished by oral cyclophosphamide therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1777–81. 10.1002/acr.20605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mok CC, Chan PT, To CH. Anti-Müllerian hormone and ovarian reserve in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:206–10. 10.1002/art.37719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hesselink D, Vangelder T. Genetic and nongenetic determinants of between-patient variability in the pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:317–21. 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann I, Fuhrmann H, Fang IF, et al. . Association between mycophenolic acid 12-h trough levels and clinical endpoints in patients with autoimmune disease on mycophenolate mofetil. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:3514–20. 10.1093/ndt/gfn360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Vives E, Segarra-Medrano A, Martinez-Valle F, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for major infections in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: influence on the disease outcome. J Rheumatol 2020;47:407–11. 10.3899/jrheum.190065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warny M, Helby J, Nordestgaard BG, et al. . Lymphopenia and risk of infection and infection-related death in 98,344 individuals from a prospective danish population-based study. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002685 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2020-001195s001.pdf (240.5KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001195s002.pdf (130.8KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001195s003.pdf (156.5KB, pdf)