Abstract

Purpose

Current acceptance of the watch-and-wait (W&W) approach by surgeons in Asia-Pacific countries is unknown. An international survey was performed to determine status of the W&W approach on behalf of the Asia-Pacific Federation of Coloproctology (APFCP).

Methods

Surgeons in the APFCP completed an Institutional Review Board-approved anonymous e-survey and/or printed letters (for China) containing 19 questions regarding nonsurgical close observation in patients who achieved clinical complete response (cCR) to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT).

Results

Of the 417 responses, 80.8% (n = 337) supported the W&W approach and 65.5% (n = 273) treated patients who achieved cCR after nCRT. Importantly, 78% of participants (n = 326) preferred a selective W&W approach in patients with old age and medical comorbidities who achieved cCR. In regard to restaging methods after nCRT, the majority of respondents based their decision to use W&W on a combination of magnetic resonance imaging results (94.5%, n = 394) with other test results. For interval between nCRT completion and tumor response assessment, most participants used 8 weeks (n = 154, 36.9%), followed by 6 weeks (n = 127, 30.5%) and 4 weeks (n = 102, 24.5%). In response to the question of how often responders followed-up after W&W, the predominant period was every 3 months (209 participants, 50.1%) followed by every 2 months (75 participants, 18.0%). If local regrowth was found during follow-up, most participants (79.9%, n = 333) recommended radical surgery as an initial management.

Conclusion

The W&W approach is supported by 80% of Asia-Pacific surgeons and is practiced at 65%, although heterogeneous hospital or society protocols are also observed. These results inform oncologists of future clinical study participation.

Keywords: Rectal neoplasms, Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, Watch and wait

INTRODUCTION

The standard management for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer is neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) followed by total mesorectal excision, which can produce good local control and long-term survival [1,2]. However, radical surgical resection can be associated with postoperative morbidities, including sexual, urinary, and sphincteric dysfunction, in addition to permanent stoma formation [3,4]. A watch-and-wait (W&W) approach for select patients with rectal cancer may also allow for the achievement of a complete clinical response (cCR) to CRT [5-7].

Evidence supporting this organ-preserving W&W paradigm has been recently reported; however, a lack of evidence from randomized clinical trials may be a hurdle for the adoption of this approach in routine clinical practice.

Current attitudes toward W&W among colorectal surgeons in Asia-Pacific countries are unknown. An international survey was performed to determine the current status of W&W paradigm use on behalf of the Asia-Pacific Federation of Coloproctology (APFCP).

METHODS

This study was approved by the Samsung Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2019-08-036-001). We designed an online survey using a google survey (https://forms.gle/zuFtVjATomWz4oim9) (Appendix). The survey consisted of 19 questions pertaining to respondent characteristics, general recognition of the W&W policy, detailed methods for CRT, and follow-up after W&W. The survey was sent anonymously to APFCP members (except for those in China) from August 31, 2019 to November 16, 2019. Printed letters were sent to the participants in China (mostly Beijing area). The IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for descriptive statistical analysis. Comparison between groups was tested using the chi-square or Fisher exact test as appropriate. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 417 participants (13.3%) responded to the survey that was sent to a total of 3,125 email or mail addresses within 3 months from initial contact. Distribution of the responders according to participating country, age, specialty, and affiliation are listed in Table 1. Twenty-three responders (5.5%) were from Australia, 79 (18.9%) from Japan, 81 (19.4%) from Korea, 202 (48.4%) from China, and the remaining responders were from Bangladesh, England, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The majority of responders (407 responders, 97.6%) were colorectal surgeons, and 379 responders (90.9%) were staff of a university or tertiary hospital.

Table 1.

General characteristics (N = 417)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Participating country (n = 14) | |

| Australia | 23 (5.5) |

| Bangladesh | 1 (0.2) |

| China | 202 (48.4) |

| England | 1 (0.2) |

| India | 4 (1.0) |

| Japan | 79 (18.9) |

| Korea | 81 (19.4) |

| Malaysia | 9 (2.2) |

| Myanmar | 1 (0.2) |

| New Zealand | 2 (0.5) |

| Philippines | 7 (1.7) |

| Singapore | 2 (0.5) |

| Thailand | 2 (0.5) |

| Vietnam | 1 (0.2) |

| Not available | 2 (0.5) |

| Age (yr) | |

| 30–39 | 90 (21.6) |

| 40–49 | 179 (42.9) |

| 50–59 | 114 (27.3) |

| 60–69 | 33 (7.9) |

| 70–71 | 1 (0.2) |

| Colorectal surgeon | |

| Yes | 407 (97.6) |

| No | 10 (2.4) |

| Affiliation | |

| University or tertiary hospital | 379 (90.9) |

| Others | 38 (9.1) |

| Department of Radiation Oncology | |

| Yes | 370 (88.7) |

| No | 47 (11.3) |

General recognition

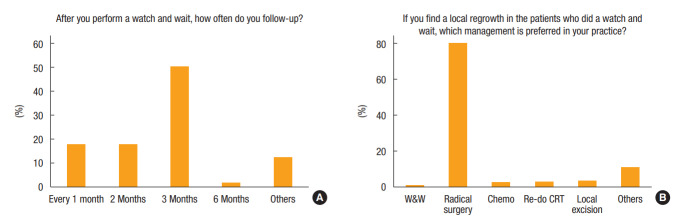

Of the 417 responders, 80.8% (n = 337) supported the W&W approach, and 65.5% (n = 273) practiced this approach in patients with cCR after nCRT (Fig. 1). Seventy-eight percent of surgeons (n = 323) explained the W&W option to patients showing cCR after nCRT. Importantly, 78% of responders (n = 326) preferred a selective W&W approach in patients with old age and medical comorbidities who achieved cCR, whereas 13% (n = 54) performed radical surgery regardless of clinical response, and 9% (n = 37) always recommended W&W.

Fig. 1.

Questions regarding general recognition for the watch-and-wait (W&W) policy: (A) acceptance of W&W, (B) experience with W&W, (C) choice in patients with clinical complete response (cCR), (D) option for cCR, (E) reasons for not performing W&W, and (F) future plans for W&W.

Responders were able to select multiple responses to questions # 5 and #7; thus, percentages do not sum to 100%. Lack of experience with this policy (n = 144, 34.5%) was mainly due to inaccuracy of current evaluation methods (n = 93), followed by lack of evidence supporting W&W (n = 87), personal memory of treatment failure (n = 17), legal issues (n = 17), failure of patient informed consent (n = 7), and lack of a radiation facility (n = 5). However, 69% of participants (71 of 103) who had not recommended W&W were willing to do so in the near future (Fig. 1).

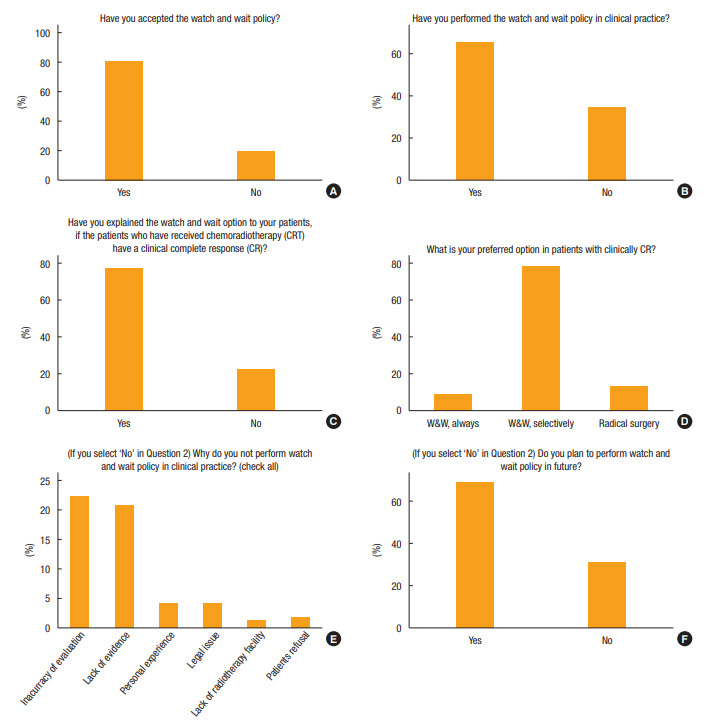

Methods for CRT

In regard to restaging methods after nCRT, the majority based their decision to use W&W on a combination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (94.5%, n = 394), sigmoidoscopy with biopsy (70.3%, n = 293), computed tomography (CT) (57.8%, n = 241), positron emission tomography (PET)-CT (27.3%, n = 114), endo-rectal ultrasound (9.1%, n = 38), and digital rectal examination (4.6%, n = 19) (Fig. 2). The predominant combination reported in this study was CT and/or PET and MRI with sigmoidoscopy and biopsy (213 responders, 51.1%), followed by CT and/or MRI (109 responders, 26.1%), CT and/or MRI with sigmoidoscopy and biopsy (77 responders, 18.5%), CT and/or PET-CT and MRI (14 responders, 3.4%), and sigmoidoscopy only (4 responders, 1%).

Fig. 2.

Methods for chemoradiotherapy: (A) restaging method, (B) radiation dose, (C) chemotherapy regimen, (D) chemotherapy during resting period, (E) chemotherapy regimen during resting period, and (F) evaluation time. CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; DRE, digital rectal examination; US, ultrasound; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Of all respondents, 53.2% (222 people) preferred a radiation dose of 5,040 cGy and 55.6% (232 people) favored capecitabine as a chemotherapy regimen. In addition, 43.4% (n = 181) maintained chemotherapy during the resting period, and 67.9% (127 of 187) repeated the same chemotherapeutic regimen if indicated. For interval between nCRT completion and tumor response assessment, most participants used 8 weeks (n = 154, 36.9%), followed by 6 weeks (n = 127, 30.5%), and 4 weeks (n = 102, 24.5%) (Fig. 2).

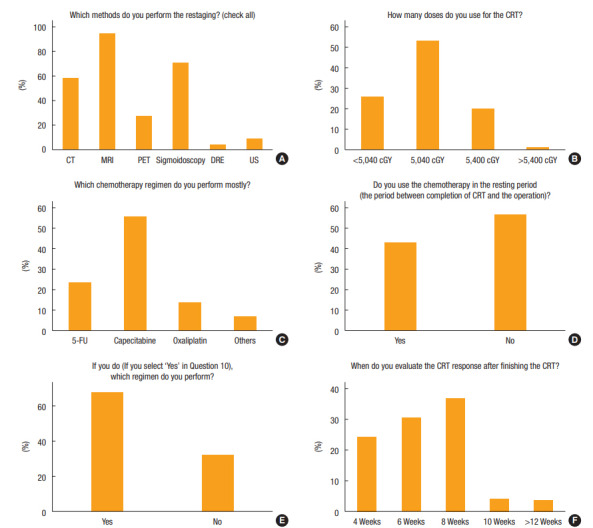

Follow-up after W&W

In response to the question of how often the responders followed-up after W&W, the predominant period was every 3 months (209 responders, 50.1%), followed by every 2 months (75 responders, 18.0%) and every month (74 responders, 17.7%) (Fig. 3). If local regrowth was found during follow-up, most responders (79.9%, n = 333) recommended radical surgery as an initial management (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Follow-up after W&W: (A) follow-up interval and (B) treatment for local regrowth. CRT, chemoradiotherapy.

Comparison between countries

Current adoption of the W&W approach between countries is compared in Table 2. Age, affiliation, acceptance of W&W, experience in clinical practice, informed consent in the case of cCR, reasons for refusal, future plans, restaging methods, radiation dose, chemotherapy regimen, interval between nCRT and evaluation, regular follow-up periods, and management of local regrowth were significantly different between countries. Participants in China favored the W&W policy in clinical practice compared to all other countries. The preferred treatment option for local regrowth was radical surgery by most surgeons from South Korea.

Table 2.

Comparison according to country

| Variable | China | Japan | Korea | Others | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | <0.001 | ||||

| 30–39 | 63 (31.2) | 0 (0) | 19 (23.5) | 8 (14.5) | |

| 40–49 | 98 (48.5) | 26 (32.9) | 33 (40.7) | 22 (40.0) | |

| 50–59 | 37 (18.3) | 40 (50.6) | 21 (25.9) | 16 (29.1) | |

| 60–69 | 4 (2.0) | 13 (16.5) | 8 (9.9) | 8 (14.5) | |

| 70–71 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Colorectal surgeon | 0.830 | ||||

| Yes | 195 (96.5) | 79 (100) | 81 (100) | 52 (94.5) | |

| No | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.5) | |

| Affiliation | 0.046 | ||||

| University or tertiary hospital | 189 (93.6) | 70 (88.6) | 75 (92.6) | 45 (81.8) | |

| Others | 13 (6.4) | 9 (11.4) | 6 (7.4) | 10 (18.2) | |

| Department of Radiation Oncology | 0.073 | ||||

| Yes | 185 (91.6) | 66 (83.5) | 74 (91.4) | 45 (81.8) | |

| No | 17 (8.4) | 13 (16.5) | 7 (8.6) | 10 (18.2) | |

| Acceptance of W&W | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 178 (88.1) | 67 (84.8) | 54 (66.7) | 38 (69.1) | |

| No | 24 (11.9) | 12 (15.2) | 27 (33.3) | 17 (30.9) | |

| Experience with W&W in clinical practice | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 160 (79.2) | 34 (43.0) | 40 (49.4) | 39 (70.9) | |

| No | 42 (20.8) | 45 (57.0) | 41 (50.6) | 16 (29.1) | |

| Informed consent in case of clinical CR | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 174 (86.1) | 48 (60.8) | 55 (67.9) | 46 (83.6) | |

| No | 28 (13.9) | 31 (39.2) | 26 (32.1) | 9 (16.4) | |

| Preferred option in clinical CR | 0.531 | ||||

| W&W, always | 16 (7.9) | 5 (6.3) | 6 (7.4) | 10 (18.2) | |

| W&W, selectively | 163 (80.7) | 62 (78.5) | 63 (77.8) | 38 (69.1) | |

| Radical surgery | 23 (11.4) | 12 (15.2) | 12 (14.8) | 7 (12.7) | |

| Reasons for refusal of W&W (multiple) | |||||

| Inaccuracy of imaging | 167 (82.7) | 57 (72.2) | 55 (67.9) | 45 (81.8) | 0.025 |

| Lack of evidence | 182 (90.1) | 49 (62.0) | 54 (66.7) | 45 (81.8) | <0.001 |

| Personal experience | 7 (3.5) | 3 (3.8) | 5 (6.2) | 2 (3.6) | 0.581 |

| Legal issue | 7 (3.5) | 1 (1.3) | 9 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0.580 |

| Lack of radiotherapy facility | 2 (1.0) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.445 |

| Patient refusal | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.5) | 0.269 |

| Plan for W&W in the future | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1 (0.5) | 38 (48.1) | 24 (39.4) | 8 (14.5) | |

| No | 2 (1.0) | 7 (8.9) | 17 (21.0) | 6 (10.9) | |

| NA | 199 (98.5) | 34 (43.0) | 40 (49.4) | 41 (74.5) | |

| Restaging methods (multiple) | |||||

| CT | 69 (34.2) | 72 (91.1) | 67 (82.7) | 33 (60.0) | <0.001 |

| MRI | 196 (97.0) | 70 (88.6) | 76 (93.8) | 52 (94.5) | 0.274 |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 122 (60.4) | 68 (86.1) | 65 (80.2) | 38 (69.1) | <0.001 |

| PET-CT | 41 (20.3) | 43 (54.4) | 5 (6.2) | 25 (45.5) | 0.089 |

| Ultrasound | 12 (5.9) | 7 (8.9) | 13 (16.0) | 6 (9.1) | 0.061 |

| Digital rectal examination | 9 (4.5) | 2 (2.5) | 4 (4.9) | 4 (7.3) | 0.455 |

| Doses for radiation | 0.003 | ||||

| <5,040 cGy | 67 (33.2) | 32 (40.5) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (9.1) | |

| 5,040 cGy | 89 (44.1) | 32 (40.5) | 68 (84.0) | 33 (60.0) | |

| 5,400 cGy | 42 (20.8) | 14 (17.7) | 10 (12.3) | 17 (30.9) | |

| >5,040 cGy | 4 (2.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen | <0.001 | ||||

| 5-Fluorouracil | 25 (12.4) | 14 (17.7) | 30 (37.0) | 29 (52.7) | |

| Capecitabine | 137 (67.8) | 33 (41.8) | 43 (53.1) | 19 (34.5) | |

| Oxaliplatin | 36 (17.8) | 10 (12.7) | 8 (9.9) | 5 (9.1) | |

| Others | 4 (2.0) | 22 (27.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Chemotherapy during the resting period | <0.001 | ||||

| Same regimen of CRT | 90 (44.6) | 19 (24.1) | 11 (13.6) | 7 (12.7) | |

| Different regimen of CRT | 36 (17.8) | 7 (8.9) | 10 (12.3) | 7 (12.7) | |

| None | 76 (37.6) | 53 (67.1) | 60 (74.1) | 41 (74.5) | |

| Interval between CRT and evaluation | 0.009 | ||||

| 4 Weeks | 42 (30.7) | 17 (21.5) | 15 (18.5) | 8 (14.5) | |

| 6 Weeks | 59 (29.2) | 17 (21.5) | 37 (45.7) | 14 (25.5) | |

| 8 Weeks | 74 (36.6) | 40 (50.6) | 28 (34.6) | 30 (54.5) | |

| 10 Weeks | 5 (2.5) | 5 (6.3) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (5.5) | |

| 12 Weeks | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| >12 Weeks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Follow-up | 0.031 | ||||

| Every month | 60 (29.7) | 4 (5.1) | 8 (9.9) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Every 2 months | 39 (19.3) | 16 (20.3) | 14 (17.3) | 6 (10.9) | |

| Every 3 months | 62 (30.7) | 56 (70.9) | 49 (60.5) | 42 (76.4) | |

| Every 6 months | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (4.9) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Others | 41 (20.3) | 2 (2.5) | 6 (7.4) | 3 (5.5) | |

| Management for local regrowth | <0.001 | ||||

| Wait and follow-up | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Radical surgery | 146 (72.3) | 64 (81.0) | 74 (91.4) | 49 (89.1) | |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (1.0) | 5 (6.3) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Repeat CRT | 9 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Proton therapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Local excision | 0 (0) | 8 (10.1) | 4 (4.9) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Others | 42 (20.8) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.8) |

Values are presented as number (%).

W&W, watch-and-wait; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; CR, complete response; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computed tomography; NA, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

Management of rectal cancer has evolved substantially over the past 2 decades. Neoadjuvant CRT followed by radical surgery remains the gold standard for locally advanced rectal cancer but is potentially associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality, sexual and urinary dysfunction, and bowel dysfunction as well as risk of permanent stoma [3,4,8]. The organ-preserving strategies including close observation following cCR to nCRT have gained attention and are supported by growing evidence [6,7,9,10]. In 2014, Habr-Gama et al. [7] reported that 31% of patients experienced local regrowth by 60 months, of whom 93% were amenable to salvage (90 of 183 patients). They reported 5-year cancer-specific overall survival and disease-free survival of 91% and 68%, respectively. Appelt et al. [6] demonstrated that 75% of patients achieved cCR, and 15% showed regrowth at 1 year after high-dose CRT for 6 weeks (60 Gy in 30 fractions) in 2015. Of note, all patients were salvageable with overall survival and disease-free survival at 2 years. In 2016, the OnCoRe project compared survival between cCR and W&W (n = 109) and surgical resection (n = 109) after CRT in a propensity-score matched cohort [10]. Local regrowth rate was 34% with a median of 33 months follow-up; 88% of patients with nonmetastatic local regrowth were salvageable. That study found no differences in 3-year nonregrowth disease-free survival and 3-year overall survival between the 2 groups. In addition, colostomy-free survival was better in the observational group (74% vs. 47%).

Despite such findings, use of the W&W protocol is undefined and uncertain. Currently, no universal guidelines on findings or methods that accurately predict cCR following nCRT are established. In addition, no randomized control trials evaluating close observation after CRT are available, probably due to logistical obstacles. Most of the published data available on W&W are from retrospective analyses with heterogeneous populations, highlighting the importance of our international survey of surgical oncologists. Habr-Gama et al. [11] performed a national survey in Brazil regarding rectal cancer management in 2011. They reported that the W&W approach in patients with cCR after nCRT was preferred by almost one-third of all participants, and surgeons showed a more favorable opinion than medical oncologists (44.7% vs. 14.2%). In 2010, a national survey in Great Britain and Ireland showed that 58% of surgeons would never consider W&W in patients with cCR, and 69% of participants would not discuss the option of nonoperative management in rectal cancer patients [12]. The 2019 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend W&W in patients who achieved cCR after nCRT in view of a clinical trial or national registry [13]. In 2018, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) conducted an international survey for global practices of W&W with members of American, European, Australian/New Zealand, and Brazilian colorectal societies [14]. They reported that 41% of ASCRS respondents trusted the W&W paradigm compared to 75% of non-ASCRS respondents. They also concluded that W&W seemed to be widely practiced throughout the world, despite the lack of a standard protocol in most institutions (ASCRS: 55% vs. non-ASCRS: 83%).

Here, we present results of an international survey about W&W in patients who achieved cCR after nCRT in Asia-Pacific countries. We found high support for the W&W approach among surgeons in the APFCP. Eighty percent of responders supported the W&W strategy, and 65.5% of responders used such a strategy for cCR after nCRT. This is the first international survey on contemporary views of the W&W approach in Asia-Pacific countries. The low response rate is the major limitation to our study. Response bias, as well as the unequal distribution of participants with up to 48% of replies from China, could have potentially influenced our results. However, we received over 400 replies, over 97% of which were from colorectal surgeons and over 90% were from a university or tertiary hospital. This critical mass indicates the validity of the results and provides a general overview about the use of the W&W strategy in clinical practice in Asia-Pacific countries and also presents opinions regarding several critical issues.

In conclusion, our survey provides current views of a W&W approach for patients who achieved clinical complete response after nCRT among specialized surgeons in Asia-Pacific countries. Our analysis suggests high support for the W&W strategy in clinical practice in our area. These results will be useful for designing future prospective clinical trials in Asia-Pacific countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the MediOffice and Dr. Xiaolong Ma for collecting survey data.

Appendix.

Questionnaire (Current Status of Watch-and-Wait Policy for Irradiated Rectal Cancer in Asia-Pacific Countries 2019 by APFCP)

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EM, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:575–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: an international multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:585–91. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paun BC, Cassie S, MacLean AR, Dixon E, Buie WD. Postoperative complications following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2010;251:807–18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dae4ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dossa F, Chesney TR, Acuna SA, Baxter NN. A watch-and-wait approach for locally advanced rectal cancer after a clinical complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:501–13. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelt AL, Pløen J, Harling H, Jensen FS, Jensen LH, Jørgensen JC, et al. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:919–27. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, São Julião GP, Proscurshim I, Sabbagh C, Lynn PB, et al. Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:822–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, Asano T, Cohen Z, Swallow CJ, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–23. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Beets GL, Figueiredo NL, et al. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2018;391:2537–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renehan AG, Malcomson L, Emsley R, Gollins S, Maw A, Myint AS, et al. Watch-and-wait approach versus surgical resection after chemoradiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer (the OnCoRe project): a propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:174–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, São Julião GP, Proscurshim I, Nahas SC, Gama-Rodrigues J. Factors affecting management decisions in rectal cancer in clinical practice: results from a national survey. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10151-010-0655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynn GR, Bhasin N, Macklin CP, George ML. Complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer: opinions of British and Irish specialists. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:327–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmar KL, Malcomson L, Renehan AG. Watch and wait or surgery for clinical complete response in rectal cancer: a need to study both sides. Colorectal Dis. 2019 Nov 21; doi: 10.1111/codi.14912. [Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartzberg DM, Grieco MJ, Timen M, Grucela AL, Bernstein MA, Wexner SD. Is the whole world watching and waiting? An International Questionnaire on the current practices of ‘Watch & Wait’ rectal cancer treatment. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:1069. doi: 10.1111/codi.14397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]