Superconducting simulators are used to investigate dynamical phase transitions, revealing their applications in quantum metrology.

Abstract

Nonequilibrium quantum many-body systems, which are difficult to study via classical computation, have attracted wide interest. Quantum simulation can provide insights into these problems. Here, using a programmable quantum simulator with 16 all-to-all connected superconducting qubits, we investigate the dynamical phase transition in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model with a quenched transverse field. Clear signatures of dynamical phase transitions, merging different concepts of dynamical criticality, are observed by measuring the nonequilibrium order parameter, nonlocal correlations, and the Loschmidt echo. Moreover, near the dynamical critical point, we obtain a spin squeezing of −7.0 ± 0.8 dB, showing multipartite entanglement, useful for measurements with precision fivefold beyond the standard quantum limit. On the basis of the capability of entangling qubits simultaneously and the accurate single-shot readout of multiqubit states, this superconducting quantum simulator can be used to study other problems in nonequilibrium quantum many-body systems, such as thermalization, many-body localization, and emergent phenomena in periodically driven systems.

INTRODUCTION

Quantum simulation uses a controllable quantum system to mimic complex systems or solve intractable problems (1, 2). Emergent phenomena in out-of-equilibrium quantum many-body systems (3), e.g., thermalization (4) versus localization (5), and time crystals (6), have all been recently studied using quantum simulation. Recently, the dynamical phase transition (DPT) and the nonequilibrium phase transition in transient time scales have been theoretically studied in the transverse-field Ising model with all-to-all interactions (7–9). These two transitions can be characterized by the nonequilibrium order parameter (7–10) and the Loschmidt echo associated with the Lee-Yang-Fisher zeros in statistical mechanics (11), respectively. Moreover, recent experimental progress has allowed the controllable simulation of these exotic phenomena with cold atoms (12, 13) and trapped ions (14, 15). Yet, experimental explorations for the dynamics of entanglement, as a valuable resource in quantum information processing, remain limited in the presence of a DPT.

In our experiments, applying a sudden change of the transverse field with a controllable strength, we drive the system, initially in its ground state, out of equilibrium. Accurate single-shot readout techniques enable us to synchronously record the dynamics of all qubits and to observe essential signatures of DPTs and spin squeezing from the dynamical criticality in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick (LMG) model. It is worth mentioning that our experimental system is a 16-qubit device featuring all-to-all connectivity, which complements the type of superconducting circuits used in other simulations of many-body physics (16–20), where neighboring couplings dominate. The presence of long-range interactions is essential for realizing the LMG model.

This work presents a systematic quantum simulation of DPTs with two different concepts, providing evidence of the relation between the nonequilibrium order parameter and the Loschmidt echo. We verify entanglement in spin-squeezed states generated from dynamical criticality, directly observing squeezing of −7.0 ± 0.8 dB for 16 qubits.

RESULTS

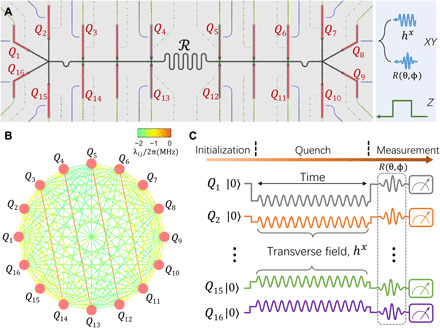

Our quantum simulator is a superconducting circuit with 20 fully controllable transmon qubits capacitively coupled to a resonator bus ℛ (Fig. 1A). Sixteen qubits (Q1 to Q16), with XY-control lines, are selected to perform experiments (see Materials and Methods). The resonant frequency of ℛ is fixed at about 5.51 GHz, while the qubit frequencies are individually tunable via their Z-control lines, enabling us to engineer the qubit-qubit interactions induced by ℛ. We detune all 16 qubits from ℛ by, e.g., Δ/2π≃ −450 MHz to switch on the resonator-mediated interactions between two arbitrary qubits (21). Simultaneously, identical resonant microwave drives, with a magnitude of hx, are imposed on all qubits to generate the local transverse fields for the control of a DPT (Fig. 1C). To ensure the uniformity of the local fields, the cross-talk effects of microwave pulses have been precisely corrected, and the microwave phase has been calibrated (see the Supplementary Materials). The effective Hamiltonian of the quenched system is

| (1) |

where N = 16, is the qubit-qubit coupling strength, gj represents the coupling strength between ℛ and Qj, and gigj/Δ is the resonator-induced virtual coupling strength, which acts as a dominant part (parameters are shown in the Supplementary Materials). Because the values of λij are nearly the same for most pairs of qubits and do not decay over distance ∣i − j∣ (Fig. 1B), the quenched system can be reasonably approximated by the LMG model, whose Hamiltonian is

with and μ = 2hx (see Materials and Methods). The LMG model was first introduced in nuclear physics (22) and then used to describe two-mode Bose-Einstein condensates (23). Recent studies (7–10, 14) have shown that HLMG has a dynamical critical point separating the dynamical paramagnetic phase (DPP) and the dynamical ferromagnetic phase (DFP) with and without a global ℤ2 symmetry, respectively.

Fig. 1. Quantum simulator and experimental pulse sequences.

(A) False-color optical micrograph of the device highlighting various circuit elements such as qubits (red), the resonator bus (black), qubit XY-control lines (blue), and Z-control lines (green). (B) Connectivity graph of the 16-qubit system when all qubits are equally detuned from the resonator bus by Δ/2π ≃ −450 MHz, with the colored straight lines representing the magnitude of the qubit-qubit couplings. Four pairs of qubits (Q3 and Q14), (Q4 and Q13), (Q5 and Q12), and (Q6 and Q11) have relatively small couplings because of their noticeable cross-talk couplings that neutralize the resonator-induced parts. (C) Experimental pulse sequences for simulating the DPT. First, the qubits are initialized in the ∣00…0〉 state at their corresponding idle frequencies. Then, the rectangular pulses and resonant microwave pulses are applied almost simultaneously to realize the quantum quench. Last, the 16-qubit joint readout is executed, yielding the probabilities {P00…0, P00…1, …, P11…1}, from which can be calculated. When necessary, single-qubit rotation pulses (in black dotted box) are applied in advance to bring the axis defined by (θj, ϕj + π/2) in the Bloch sphere of Qj to the σz direction before the readout.

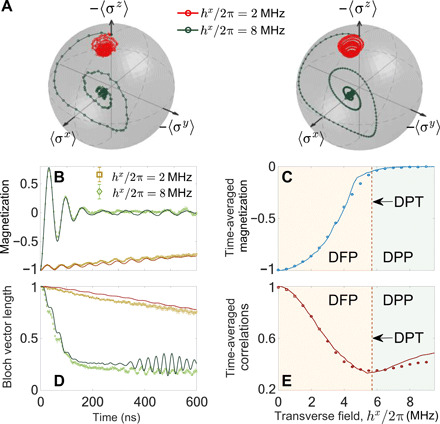

First, we show that our programmable superconducting qubits can simulate and verify the DPT by measuring the magnetization and the spin correlation. The system is initialized at the eigenstate ∣00…0〉 of H1 with hx = 0, where ∣0〉 denotes the ground state of a qubit. Then, we quench the system by suddenly adding a transverse field and monitor its dynamics from t = 0 to 600 ns. With the precise full control and the high-fidelity single-shot readout of each qubit, we are able to omnidirectionally track the evolutions of the average magnetization

along the x, y, z axes for different strengths of the quenched transverse fields, with α ∈ {x, y, z}. By depicting the trajectory of the Bloch vector , the dynamics of our quantum simulator with two distinct transverse fields is visualized in Fig. 2A. For a small transverse field, e.g., hx/2π ⋍ 2 MHz, 〈σz(t)〉 exhibits a slow relaxation (Fig. 2B). However, given a strong transverse field, e.g., hx/2π ⋍ 8 MHz, 〈σz(t)〉 exhibits a large oscillation at an early time and approaches zero in the long-time limit (Fig. 2B). In Fig. 2C, we show the behavior of the time-averaged magnetization

defined as the nonequilibrium order parameter. Figure 2C demonstrates that and in the DFP and the DPP, respectively. The experimental data of for qubits with different detunings Δ are presented in the Supplementary Materials. In addition, the Bloch vector length also depends on the strength of the transverse field hx. For large hx, decays rapidly to a small value, indicating strong quantum fluctuations in the DPP (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Magnetization and spin correlation.

(A) Experimental (left) and numerical (right) data of the time evolution of the average spin magnetization shown in the Bloch sphere for different strengths of the transverse fields. (B) Time evolution of the magnetization 〈σz(t)〉. (C) Nonequilibrium order parameter , as a function of hx/2π. (D) Dynamics of the Bloch vector length . (E) Averaged spin correlation versus hx/2π. The regions with light red and light blue in (C) and (E) show the DFP and DPP, respectively, separated by a theoretically predicted critical point . The solid curves in (B) to (E) are the numerical results using the Hamiltonian of our experimental system without considering decoherence.

Figure 2E shows the averaged spin correlation function

versus hx with a final time tf = 600 ns, where the DPT is characterized by the local minimum of two-spin correlations. We can observe the critical behaviors of and as the signatures of the DPT, when the transverse field strength is set near the theoretical prediction , with (see Materials and Methods). In the Supplementary Materials, we also present the experimental results of and for 12 and 8 qubits, clarifying finite-size effects. Experimentally, we still observe the DPT signatures down to 8 qubits.

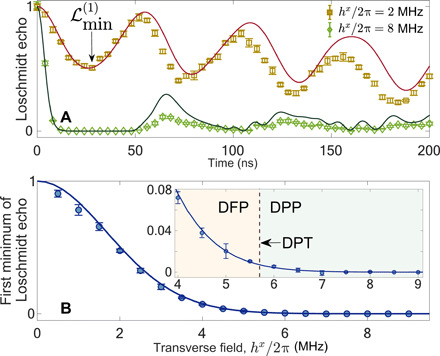

Another perspective on dynamical criticality is based on the Loschmidt echo, defined as L(t)=∣⟨00…0∣∣00…0⟩∣2, where the time t, satisfying L(t) = 0, is a Lee-Yang-Fisher zero. The zero will cause the non-analytical behavior of the rate function r(t) = − N−1 log [L(t)], regarded as the complex-plane generalization of the free-energy density (11, 24). Recent numerical studies (7, 9, 24, 25) have revealed that the existence of Lee-Yang-Fisher zeros closely relates to the DPT between the DFP and the DPP in long-range interacting systems. In Fig. 3A, we show the distinct behaviors of the Loschmidt echo in different dynamical phases. In the DPP (hx/2π ⋍ 8 MHz), the Loschmidt echo decays rapidly to a near-zero value, related to the occurrence of the non-analyticity of the rate function r(t). A clearer signature can be seen from the first minimum of the Loschmidt echo as a function of hx (Fig. 3B). In the Supplementary Materials, we clarify the reason of choosing as a circumstantial probe of the dynamical criticality, and the numerical results of the rate function r(t) using the real parameters of our quantum simulator are also presented as reference. The direct observation of the non-analytical points of the rate function r(t), as a diagnostic signature of the dynamical criticality, deserves further experimental investigations.

Fig. 3. Loschmidt echo.

(A) Time evolution of the Loschmidt echo L(t) for different transverse field strengths. (B) Earliest minimum point of L(t) during its dynamics, , as a function of hx/2π. It is shown that is close to zero in the DPP, while it becomes relatively large in the DFP. The behavior of versus hx is similar to that in the LMG model (see the Supplementary Materials). The solid curves in (A) and (B) are the numerical results using Eq. 1 without considering decoherence.

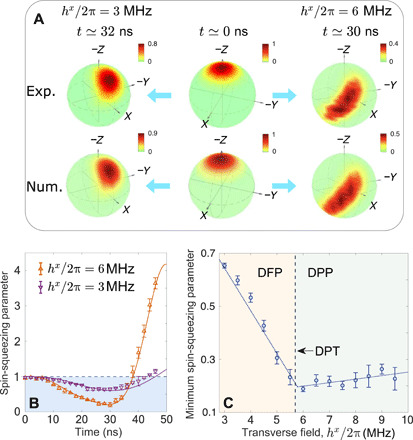

In addition to demonstrating a DPT, the LMG model is also useful for generating spin-squeezed states with twist-and-turn dynamics (26, 27). Near the equilibrium critical point, spin squeezing can be achieved, originating from quantum fluctuations, according to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (28). Similarly, we show that spin-squeezed states can also be generated from dynamical criticality. During the dynamics of the quenched Hamiltonian Eq. 1, we can visualize the spin-squeezed state by measuring the quasidistribution Q-function (29) Q(θ, ϕ) ∝ ⟨θ, ϕ∣ρ(t)∣θ, ϕ⟩, where is the spin coherent state. The measurement is realized by applying a single-qubit rotation to bring the axis defined by (θ, ϕ) in the Bloch sphere to the z axis for each qubit before the joint readout. The experimental and numerical data of Q(θ, ϕ) are compared in Fig. 4A, which show spin squeezing with a large strength of the external field, due to stronger quantum fluctuations in the DPP (see also Fig. 2C).

Fig. 4. Quasidistribution Q-function and spin-squeezing parameter.

(A) Experimental and numerical data of Q(θ, ϕ) in spherical coordinates, when the minimum values of the spin-squeezing parameters are achieved during the time evolutions with the strengths of the transverse fields hx/2π ≃ 3 and 6 MHz, respectively. (B) Time evolution of the spin-squeezing parameters with hx/2π ≃ 3 and 6 MHz, respectively. (C) Minimum spin-squeezing parameter as a function of hx. The solid lines in (B) are the numerical results using the Hamiltonian of our experimental system without considering decoherence. The blue shaded area in (B) is only accessible for entangled states. The dotted line in (C) is the piecewise linear fit, whose minimum point is close to the theoretically predicted critical point (dashed line).

We also measured the time-evolved spin-squeezing parameter (26) (see the Supplementary Materials)

| () | 2 |

where denotes an axis perpendicular to the mean spin direction, and . In Fig. 4B, we show that ξ2 < 1, as a sufficient condition for particle entanglement (30, 31), occurs in the time interval t ≲ 46 ns when hx/2π ⋍ 3 MHz, and for t ≲ 38 ns when hx/2π ⋍ 6 MHz. The minimum spin-squeezing parameter over time, , as a function of hx is shown in Fig. 4C, where the minimum value is attained very close to the critical point of the DPT. Compared with the theoretical limit, about N−2/3, of the squeezing parameter for an N-body one-axis twisting Hamiltonian (30), our 16-qubit system achieves a spin-squeezing parameter satisfying , with α ≃ 0.58. This indicates the high-efficiency generation of the spin-squeezed state from dynamical criticality and reveals a potential application of the DPT to quantum metrology.

DISCUSSION

We have presented clear signatures and entanglement behaviors of the DPT in the LMG model with a superconducting quantum simulator featuring all-to-all connectivity, including the nonequilibrium order parameter, Loschmidt echo, and spin squeezing. On the basis of its high degree of controllability, precise measurement, and long decoherence time, our platform with all-to-all connectivity is powerful for generating multipartite entanglement (29, 32) and investigating nontrivial properties of out-of-equilibrium quantum many-body systems, such as many-body localization (33, 34), quantum chaos in Floquet systems (35), and quantum annealing (36).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device information and system Hamiltonian

The device used here consists of 20 frequency-tunable superconducting qubits capacitively coupled to a central resonator bus. It is the same circuit presented in (29), where more details about the device, the qubit manipulation, and the readout can be found. In table S1, we present the characteristics for the quantum simulator involving 16 of the 20 qubits, with XY-control lines, which have been relabeled in the experiments.

The unused four qubits in this device, without XY-control lines, are detuned far off resonance from the other 16 qubits to avoid interacting with them during the experiments. Thus, they will not be included in the following descriptions. The system Hamiltonian, without applying external transverse fields, can be written as

where ωℛ and ωj represent the fixed resonant frequency and the tunable frequency of Qj, respectively, while gj is the coupling strength between the Qj and resonator bus. The magnitude of the cross-talk coupling between Qi and Qj beyond the resonator-induced virtual coupling is denoted as . When equally detuning all the 16 qubits from the resonator bus by about Δ/2π ≃ −450 MHz, and simultaneously applying resonant microwaves to each qubit, the system Hamiltonian can be transformed to

with gigj/Δ being the magnitude of the resonator-mediated coupling between Qi and Qj. It acts as a dominant part of the qubit-qubit interaction terms, because the cross-talk coupling is much smaller. In Fig. 1B, we plot the connectivity graph of the total coupling strength λij for all the combinations of pairs of qubits. The individually controllable amplitude and the phase of the microwave drive on each Qj are represented by and ϕj, respectively. In our experiments, we set the uniform amplitude and phase for all qubits, leading to the Hamiltonian in Eq. 1. To ensure this uniformity, the calibration process for the microwave drives is described in the Supplementary Materials.

Relation between the quantum simulator and the LMG model

Our device can be described by the Hamiltonian in Eq. 1. With uniform couplings , the first term of Eq. 1 can be written as

where J ≡ Nλ. The second term can be directly rewritten as , with μ = 2hx. According to [S2, Sα] = 0 (α ∈ {x, y, z}), and the fact that the initial state ∣00…0〉 is an eigenstate of S2, we have

indicating that the dynamical properties of the device H1 can be approximately expressed as the ones of the LMG model

The location of the DPT critical point of the LMG model is μc = ∣J∣/2, leading to . Note that we only roughly estimate the location of the dynamical critical point of the LMG model. The numerical simulations in the main text are based on the Hamiltonian of the quantum simulator described by Eq. 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Song, Q. Guo, Z. Wang, and X. Zhang for technical support. Devices were made at the Nanofabrication Facilities at the Institute of Physics in Beijing and National Centre for Nanoscience and Technology in Beijing. The experiment was performed on the quantum computing platform at Zhejiang University. Funding: This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant nos. 2016YFA0302104, 2016YFA0300600, and 2017YFA0304300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants nos. 11934018, 11725419, and 11904393), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB28000000), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2018 M640055), the Zhejiang Province Key Research and Development Program (grant no. 2020C01019), the ARO (grant no. W911NF-18-1-0358), the JST Q-LEAP program, the JST CREST (grant no. JPMJCR1676), the JSPS Kakenhi (grant no. JP20H00134), the JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant no. P19326), FQXi, and the NTT PHI Lab. Author contributions: D.Z., H.F., and H.W. conceived the research. K.X., Z.-H.S., Y.-R.Z., H.F., and H.W. designed the experiment. H.L. and D.Z. fabricated the device. K.X. and W.L. performed the experiment. K.X. and Z.-H.S. did numerical simulations. K.X., Z.-H.S., Y.-R.Z., and H.F. analyzed the results. K.X., Z.-H.S., Y.-R.Z., F.N., H.F., and H.W. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the experimental setup, discussions of the results, and development of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/25/eaba4935/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Feynman R. P., Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgescu I., Ashhab S., Nori F., Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisert J., Friesdorf M., Gogolin C., Quantum many-body systems out of equilibrium. Nat. Phys. 11, 124–130 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigol M., Dunjko V., Olshanii M., Thermalization and its mechanism for generic isolated quantum systems. Nature 452, 854–858 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abanin D. A., Altman E., Bloch I., Serbyn M., Colloquium: Many-body localization, thermalization, and entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 021001 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao N. Y., Potter A. C., Potirniche I.-D., Vishwanath A., Discrete time crystals: Rigidity, criticality, and realizations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 030401 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Žunkovič B., Heyl M., Knap M., Silva A., Dynamical Quantum phase transitions in spin chains with long-range interactions: Merging different concepts of nonequilibrium criticality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 130601 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lerose A., Marino J., Žunkovič B., Gambassi B., Silva A., Chaotic dynamical ferromagnetic phase induced by nonequilibrium quantum fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 130603 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homrighausen I., Abeling N. O., Zauner-Stauber V., Halimeh J. C., Anomalous dynamical phase in quantum spin chains with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. B 96, 104436 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sciolla B., Biroli G., Dynamical transitions and quantum quenches in mean-field models. J. Stat. Mech. Theor. Exp. , P11003 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyl M., Polkovnikov A., Kehrein S., Dynamical quantum phase transitions in the transverse-field Ising model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 135704 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fläschner N., Vogel D., Tarnowski M., Rem B. S., Lühmann D.-S., Heyl M., Budich J. C., Mathey L., Sengstock K., Weitenberg C., Observation of dynamical vortices after quenches in a system with topology. Nat. Phys. 14, 265–268 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernien H., Schwartz S., Keesling A., Levine H., Omran A., Pichler H., Choi S., Zibrov A. S., Endres M., Greiner M., Vuletić V., Lukin M. D., Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Pagano G., Hess P. W., Kyprianidis A., Becker P., Kaplan H., Gorshkov A. V., Gong Z.-X., Monroe C., Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator. Nature 551, 601–604 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurcevic P., Shen H., Hauke P., Maier C., Brydges T., Hempel C., Lanyon B. P., Heyl M., Blatt R., Roos C. F., Direct observation of dynamical quantum phase transitions in an interacting many-body system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 080501 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Y., Ge Z.-Y., Wu Y., Wang S., Gong M., Zhang Y.-R., Zhu Q., Yang R., Li S., Liang F., Lin J., Xu Y., Guo C., Sun L., Cheng C., Ma N., Meng Z. Y., Deng H., Rong H., Lu C.-Y., Peng C.-Z., Fan H., Zhu X., Pan J.-W., Propagation and localization of collective excitations on a 24-qubit superconducting processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 050502 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Z., Zhang Y.-R., Gong M., Wu Y., Zheng Y., Li S., Wang C., Liang F., Lin J., Xu Y., Guo C., Sun L., Peng C.-Z., Xia K., Deng H., Rong H., You J. Q., Nori F., Fan H., Zhu X., Pan J.-W., Strongly correlated quantum walks with a 12-qubit superconducting processor. Science 364, 753–756 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roushan P., Neill C., Tangpanitanon J., Bastidas V. M., Megrant A., Barends R., Chen Y., Chen Z., Chiaro B., Dunsworth A., Fowler A., Foxen B., Giustina M., Jeffrey E., Kelly J., Lucero E., Mutus J., Neeley M., Quintana C., Sank D., Vainsencher A., Wenner J., White T., Neven H., Angelakis D. G., Martinis J., Spectroscopic signatures of localization with interacting photons in superconducting qubits. Science 358, 1175–1179 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.B. Chiaro, C. Neill, A. Bohrdt, M. Filippone, F. Arute, K. Arya, R. Babbush, D. Bacon, J. Bardin, R. Barends, S. Boixo, D. Buell, B. Burkett, Y. Chen, Z. Chen, R. Collins, A. Dunsworth, E. Farhi, A. Fowler, B. Foxen, C. Gidney, M. Giustina, M. Harrigan, T. Huang, S. Isakov, E. Jeffrey, Z. Jiang, D. Kafri, K. Kechedzhi, J. Kelly, P. Klimov, A. Korotkov, F. Kostritsa, D. Landhuis, E. Lucero, J. McClean, X. Mi, A. Megrant, M. Mohseni, J. Mutus, M. McEwen, O. Naaman, M. Neeley, M. Niu, A. Petukhov, C. Quintana, N. Rubin, D. Sank, K. Satzinger, A. Vainsencher, T. White, Z. Yao, P. Yeh, A. Zalcman, V. Smelyanskiy, H. Neven, S. Gopalakrishnan, D. Abanin, M. Knap, J. Martinis, P. Roushan, Growth and preservation of entanglement in a many-body localized system. arXiv:1910.06024 [cond-mat.dis-nn] (14 October 2019).

- 20.Ma R., Saxberg B., Owens C., Leung N., Lu Y., Simon J., Schuster D. I., A dissipatively stabilized Mott insulator of photons. Nature 566, 51–57 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsomokos D. I., Ashhab S., Nori F., Fully-connected network of superconducting qubits in a cavity. New J. Phys. 10, 113020 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipkin H. J., Meshkov N., Glick A. J., Validity of many-body approximation methods for a solvable model: (I). Exact solutions and perturbation theory. Nucl. Phys. 62, 188–198 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cirac J. I., Lewenstein M., Mølmer K., Zoller P., Quantum superposition states of Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 57, 1208–1218 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zauner-Stauber V., Halimeh J. C., Probing the anomalous dynamical phase in long-range quantum chains through Fisher-zero lines. Phys. Rev. E 96, 062118 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halimeh J. C., Zauner-Stauber V., Dynamical phase diagram of quantum spin chains with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. B 96, 134427 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitagawa M., Ueda M., Squeezed spin states. Phys. Rev. A 47, 5138–5143 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J., Wang X., Sun C. P., Nori F., Quantum spin squeezing. Phys. Rep. 509, 89–165 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frérot I., Roscilde T., Quantum critical metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 020402 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song C., Xu K., Li H., Zhang Y.-R., Zhang X., Liu W., Guo Q., Wang Z., Ren W., Hao J., Feng H., Fan H., Zheng D., Wang D.-W., Wang H., Zhu S.-Y., Generation of multicomponent atomic Schrödinger cat states of up to 20 qubits. Science 365, 574–577 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pezzè L., Smerzi A., Oberthaler M. K., Schmied R., Treutlein P., Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sørensen A., Duan L.-M., Cirac J. I., Zoller P., Many-particle entanglement with Bose- Einstein condensates. Nature 409, 63–66 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song C., Xu K., Liu W., Yang C.-p., Zheng S.-B., Deng H., Xie Q., Huang K., Guo Q., Zhang L., Zhang P., Xu D., Zheng D., Zhu X., Wang H., Chen Y.-A., Lu C.-Y., Han S., Pan J.-W., 10-qubit entanglement and parallel logic operations with a superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180511 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu K., Chen J.-J., Zeng Y., Zhang Y.-R., Song C., Liu W., Guo Q., Zhang P., Xu D., Deng H., Huang K., Wang H., Zhu X., Zheng D., Fan H., Emulating many-body localization with a superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 050507 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Q. Guo, C. Cheng, Z.-H. Sun, Z. Song, H. Li, Z. Wang, W. Ren, H. Dong, D. Zheng, Y.-R. Zhang, R. Mondaini, H. Fan, H. Wang, Observation of energy resolved many-body localization. arXiv:1912.02818 [quant-ph] (5 December 2019).

- 35.Neill C., Roushan P., Fang M., Chen Y., Kolodrubetz M., Chen Z., Megrant A., Barends R., Campbell B., Chiaro B., Dunsworth A., Jeffrey E., Kelly J., Mutus J., O’Malley P. J. J., Quintana C., Sank D., Vainsencher A., Wenner J., White T. C., Polkovnikov A., Martinis J. M., Ergodic dynamics and thermalization in an isolated quantum system. Nat. Phys. 12, 1037–1041 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lechner W., Hauke P., Zoller P. A., Quantum annealing architecture with all-to-all connectivity from local interactions. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500838 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Žunkovič B., Silva A., Fabrizio M., Dynamical phase transitions and Loshmidt echo in the infinite-range XY model. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 374, 20150160 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Defenu N., Enss T., Halimeh J. C., Dynamical criticality and domain-wall coupling in long-range Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. B 100, 014434 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/25/eaba4935/DC1