Polymeric micelle formulation of an immune modulator improves survival in a highly aggressive model of non–small cell lung cancer.

Abstract

About 40% of patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have stage IV cancer at the time of diagnosis. The only viable treatment options for metastatic disease are systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Nonetheless, chemoresistance remains a major cause of chemotherapy failure. New immunotherapeutic modalities such as anti–PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade have shown promise; however, response to such strategies is highly variable across patients. Here, we show that our unique poly(2-oxazoline)–based nanomicellar formulation (PM) of Resiquimod, an imidazoquinoline Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonist, had a superior tumor inhibitory effect in a metastatic model of lung adenocarcinoma, relative to anti–PD-1 therapy or platinum-based chemotherapy. Investigation of the in vivo immune status following Resiquimod PM treatment showed that Resiquimod-based stimulation of antigen-presenting cells in the tumor microenvironment resulted in the mobilization of an antitumor CD8+ immune response. Our study demonstrates the promise of poly(2-oxazoline)-formulated Resiquimod for treating metastatic NSCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most frequently diagnosed lung malignancy (constituting 80 to 85% of lung cancers) and accounts for the majority of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). Postsurgical recurrence and metastasis is a principal cause of mortality in a substantial percentage of NSCLC cases (2). Genomic profiling of lung cancer has led to the identification of therapeutically targetable mutations, paving the way for targeted therapies. Nevertheless, the benefits of such interventions are often transient due to the development of chemoresistance, which primarily stems from tumor-host cell interactions (1). The development of systemic treatments that target the tumor microenvironment is thus crucial for managing advanced NSCLC.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of immune checkpoint blockade therapy has reshaped the landscape of NSCLC treatment. Programmed death 1, more commonly known as PD-1, is an immune checkpoint protein expressed on T cells to regulate self-tolerance by inhibiting autoimmunity. Interaction of PD-1 with its cognate ligand, PD-L1, commonly expressed on macrophages and myeloid cells, generates negative feedback to inhibit T cell activation. Certain cancers overexpress PD-L1 to benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 axis–mediated suppression of adaptive immunity (3). The use of antibodies against PD-1 has shown a favorable outcome in cancers with a high expression of PD-L1 (4). However, only a minority of PD-L1–positive patients with NSCLC respond to anti–PD-1 therapy due, in part, to intratumoral and temporal heterogeneity of pathologically regulated PD-L1 expression, underscoring the role of the pathophysiological state of the tumor microenvironment in dictating treatment response to anti–PD-1 therapy (5, 6).

Advances have been made in understanding the paradoxical role of immune cells in cancer. Signaling interactions between cancer cells and neighboring immune cells lead to the protumorigenic evolution of the latter, yielding cells that lack antitumor properties (7). For instance, a large proportion of the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) display an alternatively activated endotype, which causes a shift in the T helper 1 (TH1)/TH2 cytokine balance toward a more TH2-like (anti-inflammatory) activity, resulting in an immunosuppressive niche conducive to tumor growth (8). In addition, TAMs can dampen the adaptive immune response by impeding the tumor infiltration of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (9). Of note, cancers deficient in tumor-penetrating T lymphocytes (“cold tumors”) are refractory to immunotherapy (10). Therefore, treatment strategies aimed at stimulating the T cell immune response are essential for a durable antitumor effect.

Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists are a class of immune-stimulating agents that have shown promising immune-enhancing effects in both human and animal models of cancers (11). Expressed primarily on innate immune cells, TLRs are transmembrane proteins that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which makes them an indispensable part of the innate and adaptive immunity. To date, imiquimod (Aldara; Graceway Pharmaceuticals; TLR 7 agonist) is the only TLR agonist approved by the FDA. It is administered topically as a 5% (50 mg/g) cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma, precancerous actinic keratoses, and genital and perianal warts (12, 13). Topical administration, however, is not feasible for cancers that are not accessible from the skin. Furthermore, poor solubility of small-molecule TLR ligands prevents their systemic delivery to distal tumors and metastatic sites, and therefore, efficient delivery systems are warranted (11).

The present study investigates the immunotherapeutic potential of intravenously administered, poly(2-oxazoline) (POx)–based nanomicellar formulation of Resiquimod (Resiquimod PM), a TLR 7/8 agonist chemically related to imiquimod, in a clinically relevant mouse model of metastatic NSCLC. POx is an amphiphilic triblock copolymer composed of one hydrophobic block of poly(2-butyl-2-oxazoline) (BuOx) flanked by two hydrophilic blocks of (2-methyl-2-oxazoline) (MeOx). POx micelles exhibit an exceptionally high solubilization capacity for water-insoluble drugs in single drug– and multidrug-loaded variations (14, 15). We leveraged the characteristic sub–100-nm size of POx micelles to increase the distribution of the TLR agonist by passive targeting to the tumor. Furthermore, we also evaluated the anticancer efficacy of established frontline therapies for NSCLC, including immune checkpoint blockade therapy and platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with chemosensitizers, in the same model of NSCLC.

RESULTS

Characterization of POx formulations

Coformulation of chemosensitizers and anticancer agent

Cisplatin is a standard of care for advanced NSCLC (16). However, the initial response to cisplatin is often short-lived because of the development of drug resistance (17). We hypothesized that cancer cells could be sensitized to chemotherapy by using chemosensitizers, which are agents that harbor the potential to reverse drug resistance (18). Three different chemosensitizers were evaluated for coformulation with the alkylated prodrug of cisplatin (C6CP): (i) AZD7762—a chemosensitizer that can inhibit the DNA repair activity by checkpoint kinases following treatment with DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin and, thus, improve the therapeutic margin of chemotherapy (19); (ii) VE-822—an inhibitor of ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR), a DNA damage response pathway that is exploited by cancer cells as a rescue strategy for DNA damage (20); and (iii) AZD8055—an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase. mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase involved in the regulation of cell growth and autophagy (21). Mutation in the mTOR pathway is common in NSCLC, making it a suitable choice of a chemosensitizer (22).

The hydrophobic nature of C6CP favored the easy incorporation of cisplatin into the hydrophobic micelle core. C6CP/chemosensitizer coloaded micelles were formulated at different feeding ratios of the two drugs. Four ratios (w/w) of C6CP/chemosensitizer (4/8, 6/6, 8/4, and 9/3) were screened, keeping the polymer quantity fixed. A maximum loading capacity as high as 45 weight % was obtained with the C6CP/AZD7762 coloaded micelles at a loading ratio of 2/6 (feeding ratio of 4/8). C6CP/VE-822 coloaded micelles exhibited high loading efficiency (70 to 90%) and high loading capacity (≥49%) for all the ratios tested (Table 1). In addition, the C6CP/AZD8055 coloaded micelles also displayed a high loading capacity of more than 50% for three of the four ratios tested (table S1). Micelle sizes varied with the feeding ratios, ranging from 25 to 354 nm (Table 1; see also table S1).

Table 1. Characterization of POx micelles coloaded with anticancer agent and chemosensitizers.

LE, loading efficiency; LC, loading capacity; PDI, polydispersity index.

| Checkpoint kinase inhibitor (AZD7762) and anticancer agent (C6CP) | |||||||||

|

Feeding ratio (g/liter) |

LE (%) | LC (%) |

Drug concentration in solution (g/liter) |

Deff (nm) | PDI | ||||

|

C6CP/ AZD7762/ POx |

C6CP | AZD7762 | C6CP | AZD7762 | Tot | C6CP | AZD7762 | ||

| 8/0/10 | 71.3 | – | 36.3 | – | – | 5.7 | – | 124 ± 0.5 | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| 0/8/10 | – | 73.8 | – | 37.1 | – | – | 5.9 | 64 ± 3.6 | 0.64 ± 0.02 |

| 4/8/10 | 52.5 | 77.5 | 11.5 | 33.9 | 45.4 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 25 ± 0.8 | 0.42 ± 0.02 |

| 6/6/10 | 40.0 | 70.0 | 14.5 | 25.3 | 39.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 82 ± 4.7 | 0.45 ± 0.07 |

| 8/4/10 | 38.8 | 80.0 | 19.0 | 19.6 | 38.6 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 128 ± 0.7 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| 9/3/10 | 58.9 | 90.0 | 29.4 | 15.0 | 44.4 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 112 ± 1.1 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| ATR inhibitor (VE-822) and anticancer agent (C6CP) | |||||||||

|

Feeding ratio (g/liter) |

LE (%) | LC (%) |

Drug concentration in solution (g/liter) |

Deff (nm) | PDI | ||||

|

C6CP/VE-822/ POx |

C6CP | VE-822 | C6CP | VE-822 | Tot | C6CP | VE-822 | ||

| 8/0/10 | 98.8 | – | 44.0 | – | – | 7.9 | – | 122 ± 0.9 | 0.10 ± 0.03 |

| 0/8/10 | – | 83.8 | – | 40.0 | – | – | 6.7 | 351 ± 6.7 | 0.40 ± 0.08 |

| 4/8/10 | 92.5 | 75.0 | 18.8 | 30.5 | 49.3 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 354 ± 4.7 | 0.50 ± 0.02 |

| 6/6/10 | 91.7 | 83.3 | 26.8 | 24.4 | 51.2 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 240 ± 1.9 | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| 8/4/10 | 96.3 | 85.0 | 36.5 | 16.1 | 52.6 | 7.7 | 3.4 | 211 ± 3.8 | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| 9/3/10 | 91 | 90.0 | 39.2 | 13.0 | 52.2 | 8.2 | 2.7 | 160 ± 2.4 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

Paclitaxel (PTX) was selected as the second chemotherapeutic candidate for combination with the chemosensitizer since the POx micellar formulation of PTX has been extensively studied and shown to have a drug loading capacity superior to clinically approved Abraxane, resulting in improved anticancer efficacy when administered at the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the respective formulations (14). The PTX/VE-822 combination exhibited a high loading capacity of more than 48% for all the four ratios tested (table S1).

Resiquimod PM

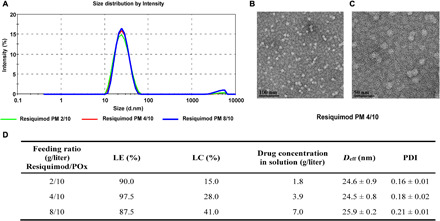

Resiquimod is an imidazoquinoline immune response modifier that stimulates TLR 7 in mice and TLR 7/8 in humans (12). We sought to formulate Resiquimod in POx micelles to improve the aqueous solubility of Resiquimod for intravenous delivery in mice. By keeping the polymer amount constant and incrementally increasing the drug amount, different feeding ratios of Resiquimod were examined. Resiquimod was well solubilized even at a high feeding ratio of 8/10, yielding a drug concentration of 7 mg/ml in saline and a loading capacity of 41% by weight. The size distribution obtained from dynamic light scattering (DLS) indicated the presence of small and monodisperse particles for feeding ratios 2/10 to 8/10 (Fig. 1, A and D). This was corroborated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which showed small and spherical particles of about 20 nm in size (Fig. 1, B and C).

Fig. 1. Physical characterization of Resiquimod PM.

(A) Particle size distribution of Resiquimod PM at different feeding ratios as a function of intensity (percentage), measured by DLS. (B and C) Transmission electron micrographs at different magnifications show the spherical morphology of Resiquimod PM particles (4/10 g/liter) and illustrate the uniformity of particle shape and size. (D) Characterization of POx micelles loaded with TLR 7/8 agonist (Resiquimod).

In vitro cytotoxicity

Anticancer agents (C6CP and PTX) and chemosensitizers (AZD7762, VE-822, and AZD8055) alone or in combination were tested for their in vitro cytotoxicity in the 344SQ lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) cell line. For the single-agent polymeric micelle controls, the drugs were tested in fivefold increments at concentrations ranging from 0.256 ng/ml to 100 μg/ml (equivalent to 0.5 nM to 188 μM for C6CP PM, 0.3 nM to 117 μM for PTX PM, 0.7 nM to 275 μM for AZD7762 PM, 0.5 nM to 215 μM for VE-822 PM, and 0.5 nM to 215 μM for AZD8055 PM). To investigate the effect of drug ratios on synergy, we tested four anticancer agent/chemosensitizer ratios (w/w) at combined concentrations of both drugs ranging from 0.256 ng/ml to 100 μg/ml. In addition, we also studied the effects of free drugs and their mixtures. The limited solubility of drugs in the absence of micelles in the cell culture medium was factored in the selection of dose range for free drugs (0.0256 ng/ml to 10 μg/ml).

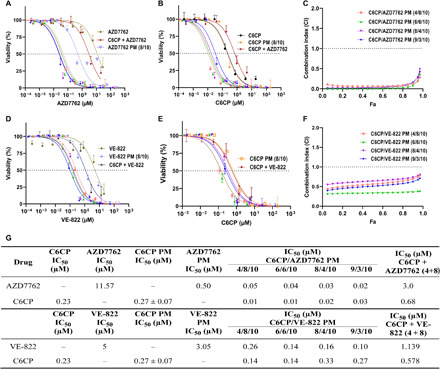

A dose-dependent decline in cell viability was observed in all treatments involving C6CP. The IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values revealed that the two-drug–loaded micelles of C6CP were generally more potent than either of the drugs used alone. Furthermore, with the exception of C6CP, the IC50 values of polymeric micelle encapsulated drugs were substantially lower than those of free drugs when compared at the same concentration range (Fig. 2, A, B, D, E, and G, and fig. S1, A, B, and G). This was also true for the mixture of two free drugs, which displayed a higher IC50 value than two-drug–loaded micelles of the same ratio. In marked contrast, PTX had minimal cytotoxic effect on this cell line. Previous research has shown that increased exposure time in conjunction with increased dose improved the cytotoxicity of PTX (23); however, following exposure to PTX for 72 hours, the cytotoxicity of PTX was found to be modest in the present study. Nonetheless, the combination of PTX and VE-822 resulted in considerably higher cytotoxicity due to the chemosensitizing activity of VE-822 (fig. S1, D, E, and G).

Fig. 2. Cytotoxicity assay of POx formulations.

In vitro cytotoxicity of anticancer agent and chemosensitizers in the 344SQ LUAD cell line (A, B, D, and E). Dose-response curves of free and micelle incorporated drugs and drug combinations in the 344SQ cell line after 72 hours of treatment. Cell viability as a function of individual drug concentrations after treatment with a combination of the drugs AZD8055 and C6CP (A and B) and VE-822 and PTX (D and E). The data were fit into sigmoidal curve using nonlinear regression. Data represent mean ± CV. n = 6. (C and F) Fa-CI plots of the C6CP/AZD7762 and C6CP/VE-822 combinations. Data represent means. n = 6. (G) Comparison of the IC50 values of POx formulations and free drugs in the 344SQ cell line.

The synergy of different drug combination ratios was studied using the combination index (CI) theorem (isobologram equation) of Chou and Talalay, which states that a CI value of less than 1 represents synergy, whereas a CI value greater than 1 indicates antagonism (24). It should be noted that the superadditive therapeutic effect of drug combinations is strongly influenced by the drug ratios (15). Every feed ratio (4/8 to 9/3) of the C6CP/AZD7762 combination yielded CI < 0.3 for cell death fraction (Fa: fraction affected) ranging from 0.1 to 0.9, suggesting a strong synergy of cotreatment. C6CP/VE-822 drug pair, too, depicted synergy for all feed ratios (CI < 1) with pronounced synergy (CI < 0.5) at the C6CP/VE-822 feed ratio of 4/8 (Fig. 1, C and F). Furthermore, C6CP/AZD8055 pair displayed maximum synergy at a feed ratio of 6:6, and while PTX/VE-822 showed synergistic effect at all feed ratios, maximum synergy was observed for the feed ratios of 8/4 and 9/3 (fig. S1, C and F). Because of the superior toxicity profile and synergistic effect of C6CP/AZD7762 and C6CP/VE-822 combinations, they were identified as lead candidates for in vivo study.

Resiquimod, on the other hand, did not exhibit any cytotoxic activity in 344SQ cells at concentrations ranging from 0.00128 to 20 μg/ml (fig. S2A). This observation is consistent with previous works that report Resiquimod as lacking a direct antineoplastic effect. However, its analog, imiquimod, has been shown to have a proapoptotic effect on a human skin cancer cell line. The distinct effects of the two TLR agonists were speculated to be due to the disparate subcellular localizations of the two compounds (25).

Characterization of Resiquimod-mediated BMDM activation in vitro

Macrophages account for a major percentage of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (26). Because of their plastic nature, TAMs are prime targets of cancer-mediated “reprogramming” to a tolerogenic (TH1/TH2 low) phenotype. Immunotherapeutic strategies aimed at resetting the TH1/TH2 ratio to restore the tumoricidal function of macrophages have shown promise in treating cancer (27). Accordingly, we sought to investigate the potential of Resiquimod PM to polarize murine bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) to an antitumor phenotype (TH1/TH2 high) via TLR stimulation.

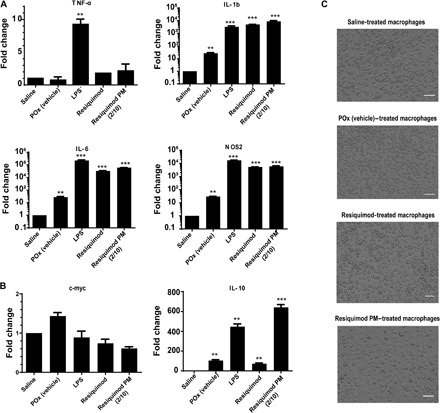

As shown previously, Resiquimod was found to lack cytotoxic effect on macrophages at the concentration used for the experiment (fig. S2B) (28). Resiquimod PM and free Resiquimod treatment of BMDM resulted in an increase in the mRNA expression of tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS2) (classical activation) in a manner similar to that of LPS (lipopolysaccharide), a TLR 4 agonist (Fig. 3A). IL-1β is an important TH1 cytokine that promotes anticancer immune response by activating and expanding CD4 and CD8 T effector cells (29). IL-6 signaling is again pivotal to the differentiation of T and B cells (30). The antitumor activity of macrophages ensues partly from NOS2 expression. NOS2 encodes inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme that catalyzes the production of tumoricidal reactive oxygen species (8). While the expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and NOS2 for the Resiquimod and LPS treatment groups were considerably enhanced, TNF-α expression was relatively modest. This could be due to the 4-hour time frame as the expression of TNF-α is reportedly low at early time points following macrophage stimulation (27).

Fig. 3. In vitro activation of BMDM.

(A) Relative mRNA expression of classically activated (M1-like) macrophage markers (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and NOS2) normalized to 18S. (B) Relative mRNA expression of M2-like macrophage markers (c-myc and IL-10) normalized to 18S. Data represent means ± SEM. n = 3. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 computed by unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. Significance level (α) was set at 0.05. (C) Cell morphology of resting macrophages and M1-polarized macrophages following Resiquimod and Resiquimod PM (2/10 g/liter) treatments (bottom). Scale bars: 50 μm.

Analysis of alternatively activated macrophage markers showed a low expression of the c-myc gene. However, treatment with Resiquimod and LPS elicited an increased expression of IL-10 (Fig. 3B). This was not unexpected because IL-10 protein expression is known to counterbalance the production of TNF-α, resulting in a low TNF-α/IL-10 ratio. The increase in TNF-α expression over time is expected to thwart the production of IL-10.

Furthermore, POx (vehicle) was found to stimulate the expression of IL-1b, IL-6, and NOS2 in BMDM, albeit to a much lower extent than Resiquimod and LPS treatments (Fig. 3A). This observation is consistent with a study by Hou-Nan Wu and co-workers that looked at macrophage stimulation by amphiphilic polymers, where polymeric micelles induced the production of TNF-α and MCP-1 from macrophages in a time-dependent manner. However, following treatment of mice with these micelles, inflammatory mediators were not detected in the plasma of these animals (31). Therefore, we believe that the macrophage stimulation effect of POx micelles is not strong enough to warrant further investigation. Following treatment with Resiquimod PM and Resiquimod, cell morphology of BMDM shifted from elongated structures in resting macrophages (saline- and POx-treated groups) to round and flattened structures, characteristic of TH1-activated macrophages (Fig. 3C) (32).

Estimation of MTD

We have previously demonstrated the hematological and immunological safety of POx by the assessment of liver and kidney function (blood chemistry panel), complement activation, and histopathology of major organs following repeated intravenous injections (q4d × 4) in mice (14). Therefore, no further toxicity analysis was performed for the polymer alone in this study. Dose-escalation study of single-agent POx micelles of C6CP, AZD7762, and VE-822 in 129/Sv mice served as a basis for the determination of doses for the combinations (fig. S3A). For both combinations, all three doses tested (2.5/5, 5/10, and 10/20 mg/kg and 10/10, 7.5/7.5, and 5/5 mg/kg for C6CP/AZD7762 PM and C6CP/VE-822 PM, respectively) were well tolerated by the mice. There was no incidence of death. Even at the highest tested dose, mice body weight did not fall below 5% of initial weight (fig. S3, C and D). Furthermore, no obvious behavioral abnormalities were observed in these mice. Accordingly, C6CP (10 mg/kg) and AZD7762 (20 mg/kg) for C6CP/AZD7762 and C6CP (10 mg/kg) and VE-822 (10 mg/kg) for C6CP/VE-822 were established as the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL).

MTD finding studies for cancer immunotherapy are confounding because, unlike chemotherapy, higher doses do not necessarily increase efficacy. The nonlinear dose-efficacy relationship of immune response modifiers makes it challenging to establish an MTD for these molecules. For this reason, most clinical studies involving immunomodulatory agents use doses below MTD (33). As for Resiquimod PM, all three tested doses were well tolerated by the mice (fig. S3B), as evidenced by the absence of any clinical signs. The body weight changes of the Resiquimod PM–treated group had a similar trend to that of the control group. Thus, 5 mg/kg was identified as a safe dose for the in vivo efficacy study.

Tumor inhibition study

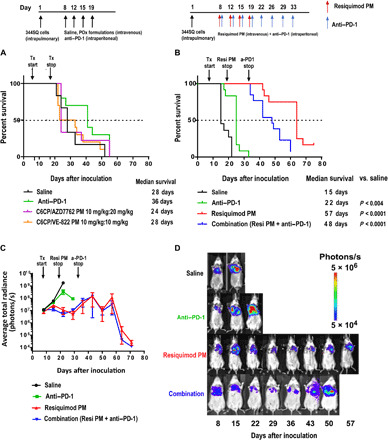

We evaluated the antitumor efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with chemosensitizers, and Resiquimod PM alone and in combination with anti–PD-1 in an immune-competent, orthotopic model of LUAD, prepared from the 344SQ LUAD cell line derived from the metastases of the genetically engineered mouse model of LUAD carrying KrasG12D and p53R172HΔG mutations. The ability to produce spontaneous metastases and, thus, recapitulate the pathophysiology of LUAD is the key strength of this model (34). The lack of any anticancer activity of POx alone has been previously demonstrated in this model (35). Unexpectedly, neither of the combination drug PMs (C6CP/AZD7762 PM and C6CP/VE-822 PM) improved survival relative to the control group despite having a strong synergistic effect in vitro. The median survival was 24 days for C6CP/AZD7762 PM and 28 days for C6CP/VE-822, which was comparable to the untreated group. Furthermore, the anti–PD-1 treatment produced a modest improvement in survival, relative to the control (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Tumor inhibition in 344SQ lung adenocarcinoma–bearing mice.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots of (A) tumor-bearing mice treated with four intravenous injections of saline, C6CP/AZD7762 PM, and C6CP/VE-822 PM. (B) Tumor-bearing mice treated with four intravenous injections of saline, Resiquimod PM, eight intraperitoneal injections of anti–PD-1 antibody, and a combination of Resiquimod PM (four intravenous injections) anti–PD-1 antibody (eight intraperitoneal injections). P values were computed by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Significance level (α) was set at 0.05. (C) Quantification of BLI signal; data represent means ± SEM. n = 13. (D) Representative IVIS images of mice from each treatment group on the days of the treatment.

Resiquimod PM monotherapy resulted in a pronounced increase in overall survival (Fig. 4B). The median survival was 57 days for this group, which was a significant improvement given the poor prognosis of this model of NSCLC. Luciferase expression of the 344SQ cell line allowed the assessment of tumor growth by bioluminescence imaging. The dose of Resiquimod PM was terminated on day 19 to assess the durability of the anticancer immune response. Despite lacking a direct anticancer effect (fig. S2A), Resiquimod PM treatment substantially suppressed tumor progression for over 20 days following the cessation of treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). Anti–PD-1 monotherapy provided a modest benefit to tumor growth. Although the combination of anti–PD-1 and Resiquimod PM performed better than anti–PD-1 alone, it did not provide any discernible benefit over Resiquimod PM monotherapy. A possible explanation for the lack of synergy between anti–PD-1 and Resiquimod PM is the development of resistance to anti–PD-1 over time due to the selection pressure on cancer cells, which drives new mutations to enable mechanisms that can suppress host immunity independently of PD-L1 (36). Chen et al. (37) have recently confirmed this by showing up-regulation of CD38 (an ectozyme shown to mediate suppression of T lymphocytes) as a mechanism for acquired resistance to anti–PD-1 in two separate lung cancer models, notably one of which included the 344SQ model. Last, the body weights of the mice from the Resiquimod PM and combination groups remained consistent when compared with mice from the saline and anti–PD-1 groups, indicating better health status (fig. S4).

Resiquimod controls LUAD growth by mediating host immune response

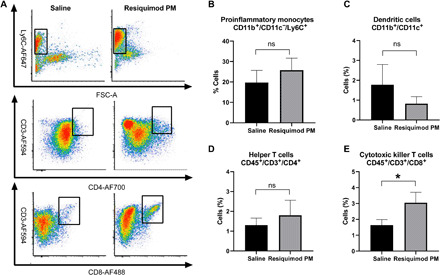

To uncover the immunomodulatory effect of Resiquimod cargo, we analyzed the immune status of the tumor microenvironment by flow cytometry at 48 hours after the second injection of Resiquimod PM in LUAD-bearing mice. Given the vital role of macrophages in regulating the inflammatory response, we sought to examine its surface profile following TLR stimulation. Tumors that received Resiquimod PM treatment showed an increased incidence of CD11b+/CD11c−/Ly6C+ monocytes (Fig. 5). Ly6C+ monocytes are prone to differentiate into inflammatory macrophages and secrete TH1 cytokines that activate adaptive immune response (38). We next investigated the influence of Resiquimod treatment on dendritic cells. The CD11b+/CD11c+-expressing dendritic cell subset was found to be reduced in the treatment group compared with the control. This observation was consistent with the finding by Decker and co-workers (39) that the CD11c marker is down-regulated upon activation of mouse dendritic cells by TLR stimulation. Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that dendritic cell activation by Resiquimod PM led to the down-regulation of the CD11c marker, yielding a low number of CD11c+ cells in the tumor. Last, we examined whether the stimulation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) led to the induction of T cell response. Flow analysis of cells triple-stained for CD45+/CD3+/CD4+ and CD45+/CD3+/CD8+ revealed an increase in the CD8+ T cell population and an upward trend in CD4+ T cell population in the tumors of the treatment group, suggesting the ability of Resiquimod monotherapy to not only mount tumor-specific immune response by CD8+ T cells but also activate the CD4+ T cell population, required for the generation of memory immune response (40).

Fig. 5. Resiquimod PM induces TH1 polarization of immune cells in the TME.

(A) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots of CD11b+/CD11c−/Ly6C+, CD45+/CD3+/CD4+, and CD45+/CD3+/CD8+ cell populations from the tumors of mice treated with saline and Resiquimod PM. FSC-A: forward scatter area. (B to E) Quantification of the indicated population of cells. Data represent means ± SEM. n = 4. *P < 0.05 computed by unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. Significance level (α) was set at 0.05. ns, not significant.

Next, we looked at serum cytokine/chemokine levels in tumor-bearing mice to assess the systemic inflammatory status at 48 hours following the second injection of Resiquimod PM. Serum titers of proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines in the Resiquimod PM–treated group did not differ significantly from the saline group (fig. S5). This was not unexpected as previous studies have shown that proinflammatory cytokines return to baseline levels approximately 24 hours after TLR agonist dosing in normal mice (41, 42). Downmodulation of systemic cytokine signaling is a widely accepted mechanism of immune system regulation involving the SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling) family of proteins to keep immune disorders caused by constitutive expression of proinflammatory proteins in check (43).

DISCUSSION

Our animal model of LUAD is developed by orthotopic injection of the Kras/p53 cell line (344SQ) into the lung of a syngeneic, immune-competent host. The 344SQ cell line is predisposed to metastasis because of loss of miR-200 family, a negative regulator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and, thus, metastasis (44). Metastatic LUADs harboring Kras/p53 mutations are associated with considerably lower numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (4). Insufficient numbers of tumor-infiltrating T cells preclude response to immunotherapeutic strategies such as anti–PD-1 therapy that primarily act on preexisting anticancer T cells (45). While this may explain the innate resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy, acquired resistance to anti–PD-1 is a consequence of evolutionary pressure on cancer cells, resulting in PD-L1–independent mechanisms of immune evasion (36, 37). An alternative approach is, therefore, necessary to treat tumors refractory to anti–PD-1.

Resiquimod is 100 times more potent (on a weight basis) as an immune response modifier than imiquimod. However, clinical trials involving topical Resiquimod have shown limited success owing to the poor systemic absorption (<1%) of local dose, resulting in suboptimal serum levels of Resiquimod (12, 46). Here, we report that our novel POx-based nanomicellar formulation of Resiquimod provides an apposite platform for the systemic administration of the TLR agonist. Resiquimod PM not only was well tolerated by mice at a dose of 5 mg/kg [intravenously (iv)] but also extended the overall survival in LUAD-bearing mice, outperforming anti–PD-1 therapy. In contrast, despite exhibiting an excellent in vitro synergistic anticancer effect, chemosensitizers and anticancer drugs coformulated in POx micelles did not display a therapeutic effect in LUAD mice compared with the control group, underscoring the insensitivity of the LUAD model to chemotherapeutic strategies.

While lacking a direct antitumor effect, Resiquimod functions by orchestrating the immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment, resulting in the mobilization of the antitumor immune response (47). Immunogenicity of Resiquimod is conferred by its close resemblance to purine bases found in RNA, which are natural ligands of TLR (12). Because TLR 7/8 are principally located intracellularly (12), encapsulation of Resiquimod in POx micelles is particularly beneficial for easy access to endosomally located TLR 7/8 following endocytic internalization of Resiquimod PM by immune cells. The association of Resiquimod and TLR 7/8 initiates the MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response 88)–dependent signaling cascade, culminating in the TH1 immune response. MyD88 is an important adaptor protein that mediates the association between TLRs and IL-1R–associated kinases (IRAKs) and thereby triggers the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and IκB kinase (IKK) complex, ultimately leading to the nuclear translocation and transcription of nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and subsequent induction of TH1 cytokines and chemokines (12, 48, 49). TH1 cytokine signaling potentiates the immune response against cancer and recruits more cells of the TH1-high endotype. Most notably, TH1 priming enhances the phagocytic activity of APCs and up-regulates the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and costimulatory molecules, resulting in the rapid phagocytosis of tumor cells and presentation of the tumor antigen to T cells in tumor-draining lymph node (TDLN), a prerequisite for the generation of tumor-specific immune response (11). Our results indicate that Resiquimod PM can effectively polarize APCs (both macrophages and dendritic cells) to an antitumor phenotype in vivo in the LUAD tumor model, corroborating our in vitro study with BMDM, and concomitantly increase the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the tumors, substantiating the potency of Resiquimod PM in generating a CTL response.

It is understood that the success of immunotherapy hinges on its ability to potentiate the immune response to cancer by acting at the right location at the right time. While POx nanoformulation of Resiquimod addresses the former requisite, the latter can be addressed by using a dosing strategy that synergizes with the natural timing of the immune response. From the recognition of tumor antigen to the infiltration of antitumor T cells, the development of immune response follows a coordinated sequence of events lasting several days (50). Accordingly, the dosing schedule in immunotherapy should be optimized to allow sufficient time for maximum APC–T cell interaction. The limitation of this study is that we do not know whether the dosing regimen chosen for the study is optimal. This will be investigated in the future with the help of suitable biomarkers that can offer a peek at the windows of opportunity for assessing the ideal time frame for dosing to amplify the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy.

Despite a promising therapeutic profile, toxicity resulting from hyperstimulation of the immune system (also known as cytokine storm) is a major bottleneck to clinical translation of TLR agonists (51). Clinical manifestations of cytokine storm range from mild (flu-like disease that is easily managed) to severe (rare but potentially life-threatening) (52). Owing to the fundamental differences in the innate immunity between mice and humans, mice do not exhibit clinical signs of cytokine storm and, therefore, may have a poor predictive value for the human disease (52, 53). Therefore, our mouse model does not allow the study of toxicities resulting from cytokine storm. Nonetheless, research on the management of the cytokine storm has demonstrated that it can be managed by blocking specific cytokines without compromising efficacy (54). A recent study by Norelli et al. (55) showed both IL-1 and IL-6 (implicated as a key driver of cytokine storm) were involved in the pathogenesis of cytokine storm in a humanized mouse model of leukemia, and because IL-1 signaling preceded IL-6, the blockade of IL-1 receptor was shown to successfully overcome the toxicities associated with the syndrome.

In summary, this study highlights the preeminent tumor inhibition activity of Resiquimod PM brought about by effective immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment and its potential to serve as an alternative to treatments that do not work on immunologically cold tumors. Although the investigation of the antitumor memory response was beyond the scope of this study, it is well recognized that activation and deployment of the adaptive immune surveillance generate long-term immunological memory that can counter cancer recurrence (56).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Triblock copolymer of P[MeOx35-b-BuOx34-b-MeOx35]-piperazine [Mn (number-average molecular weight) = 13 kDa, Mw (weight-average molecular weight)/Mn = 1.14] was synthesized by living cationic ring-opening polymerization of 2-oxazolines as described previously (57). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum was obtained using a Bruker Avance III 400-MHz spectrometer and analyzed using the MestReNova (11.0) software. The molecular weight distribution of the polymer was measured by gel permeation chromatography on a Viscotek VE2001 solvent sampling module. The alkylated prodrug of cisplatin (C6CP) was synthesized as described previously (35). Resiquimod was purchased from APExBIO (no. B1054), and Rat IgG2a, κ anti-mouse PD-1, RMP1-14 clone was purchased from BioXCell (no. BE0146). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Fisher Scientific.

POx micelle preparation and characterization

POx micelles were prepared by the thin-film hydration method. The polymer and drugs (Resiquimod, C6 cisplatin prodrug, PTX, AZD7762, VE-822, and AZD8055) were dissolved in a common solvent and subjected to mild heating (45°C) accompanied by constant nitrogen flow for complete removal of solvent to form a dried thin film. The thin film was subsequently hydrated with saline at the optimal temperature (room temperature for Resiquimod PM and 55°C for C6CP/AZD7762, C6CP/VE-822, C6CP/AZD8005, and PTX/VE-822 PMs) to get drug-loaded micelles.

The drug amount incorporated in the micelles was measured by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography on an Agilent 1200 HPLC system equipped with ChemStation software using a Nucleosil C18, 5-μm particle size column [L × inner diameter (ID) 25 cm by 4.6 mm]. The ultraviolet chromatograms of drugs were obtained using isocratic elution mode with a mobile phase of acetonitrile (ACN)/water 60/40 (v/v) and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, operated at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and a column temperature of 40°C. The micelle samples were diluted 50 times with the mobile phase, and an injection volume of 10 μl was used for all the samples. The drug loading capacity and loading efficiency of the POx micelles were calculated as described previously (14).

The size distribution of POx micelles was determined using the DLS technique on a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). Every sample was diluted 10 times with normal saline to a final polymer concentration of 1 g/liter, and the intensity-weighted Z average size was recorded for three measurements of each sample at a detection angle of 173° and a temperature of 25°C. The POx micelles were further characterized by TEM. A high-resolution JEOL 2010F FasTEM-200 kV with a Gatan charge-coupled device camera was used for image acquisition. Diluted solutions of POx micelles were dropped onto the TEM grid and allowed to dry and stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 2 min before TEM imaging.

Cell study

In vitro cytotoxicity of POx formulations on the 344SQ LUAD cell line was assessed by studying the cell viability following treatment with various concentrations of free drugs and polymeric formulations of C6CP, PTX, AZD7762, VE-822, AZD8055, C6CP/AZD7762, C6CP/VE-822, C6CP/AZD8055, PTX/VE-822, and Resiquimod, prepared by serial dilution in full medium. The 344SQ cell line was provided by J. Kurie (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). The cells were cultured in RPMI (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Five thousand cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to attach for 24 hours before treatment. Seventy-two hours following drug treatment, cell viability was measured by the Dojindo Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) using the manufacturer’s protocol. The IC50 was calculated using the GraphPad Prism 6 software. Quantification of the synergistic effect of drug combinations was done using CompuSyn software based on the CI theorem of Chou and Talalay.

In vitro activation of BMDMs

BMDMs were derived from the femur bone marrow of FVB/NJ mice per previously published protocol (58). Briefly, bone marrow cells were extracted from the bone marrow of 6- to 8-week-old mice and subjected to red blood lysis by ACK (ammonium-chloride-potassium) lysing buffer. The resulting cell suspension was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and recombinant murine macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (10 ng/ml) for 10 days. On day 11, the medium was replaced with CSF-free medium, and on the following day, the cells were treated with free and micelle-incorporated Resiquimod. For analysis of the in vitro polarization status of macrophages, total RNA was harvested from BMDM 4 hours after treatment per Qiagen RNA extraction protocol (Qiagen). RNA was then reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) using an iScript Kit (Bio-Rad). Using cDNA as a template, the gene expression of the Tnfa, il1b, il6, nos2, cmyc, il10, and mrc2 was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (relative to 18S) on QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Estimation of MTD

A dose-escalation study was used to identify the highest safe dose (MTD). Tumor-free female 8-week-old 129/Sv mice were segregated into groups of three, with each group subjected to increasing doses of drugs. Resiquimod PM (1, 3, and 5 mg/kg), C6CP/AZD7762 PM (2.5/5, 5/10, 10/20 mg/kg), and C6CP/VE-822 PM (10/10, 7.5/7.5, and 5/5 mg/kg) and normal saline (control) were injected intravenously following q4d × 4 regimen. Every mouse was assigned a unique ID. Body weight loss of 15% or greater and other signs of toxicity such as hunched posture and rough coat were set as the study endpoints. The mice were monitored every other day until the end of the study.

Animal tumor model of NSCLC

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. 344SQ murine LUAD cells expressing firefly luciferase and green fluorescent protein [in 50 μl of 1:1 mix of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) and BD Matrigel] were injected into the left lung of 8-week-old female 129/Sv mice via intrapulmonary injection as described previously (59). Briefly, mice anesthetized with ketamine + xylazine + acepromazine were laid in lateral decubitus position, and an incision was made between ribs 10 and 11 to visualize and access the lung. The cell suspension was directly injected into the lung parenchyma at the lateral dorsal axillary line, following which the incision was closed using surgical clips. The animals were monitored until full recovery.

In vivo efficacy study

Chemotherapy in conjunction with chemosensitizers

344SQ–green fluorescent protein (GFP)/fLuc cells (2.5 × 103) were orthotopically injected in the left lung of 8-week-old 129/Sv mice. Treatments were commenced a week after tumor inoculation. Baseline bioluminescence was measured using IVIS lumina optical imaging system before treatment administration. Mice randomized into groups of 10 received intravenous injections (i) normal saline, (ii) C6CP/AZD7762 PM (10/20 mg/kg), and (iii) C6CP/VE-822 PM (10/10 mg/kg), and intraperitoneal injection of anti–PD-1 antibody (250 μg per mouse) using q4d × 4 regimen. Mouse survival and body weight changes were monitored every other day. Tumor load was measured weekly by bioluminescence imaging. Mice exhibiting signs of distress such as labored breathing, restricted mobility, ruffled fur, hunched posture, weight loss of greater than 15%, and moribund state were euthanized by carbon dioxide intoxication, followed by cervical dislocation.

Immunotherapy alone and in combination with immune checkpoint blockade

A week after tumor inoculation (5 × 103 344SQ-GFP/fLuc cells in 50 μl of 1:1 mix of HBSS and BD Matrigel), the animals (n = 13) received the following injections: (i) normal saline (q4d × 4 doses, iv), (ii) Resiquimod PM (5 mg/kg; q4d × 4 doses, iv), (iii) anti–PD-1 [250 μg per mouse; q4d, intraperitoneally (ip)], and (iv) Resiquimod PM (5 mg/kg; q4d × 4 doses, iv) + anti–PD-1 (250 μg per mouse; q4d, ip). A total of four doses were administered for Resiquimod PM, whereas anti–PD-1 was continued throughout the duration of the experiment. For the combination treatment, Resiquimod PM and anti–PD-1 were administered on the same day for a total of four doses, after which anti–PD-1 was continued for an additional four doses (without Resiquimod).

Evaluation of tumor microenvironment modulation by POx/Resiquimod

Subcutaneous 344SQ LUAD (105 344SQ-GFP/fLuc cells) tumors were formed in 8-week-old 129/Sv mice. The mice were then randomly split into treatment arm [Resiquimod PM (5 mg/kg); n = 8] and control arm (normal saline; n = 8). Each group received two intravenous injections of the respective treatments on days 8 and 11 after tumor inoculation.

Flow cytometry

For examining the immune status of the tumors after treatment, the subcutaneous tumors were resected 48 hours after the second treatment. The harvested tumors were subjected to enzyme treatment [collagenase 2 mg/ml in HBSS; dispase 2.5 U/ml in HBSS; deoxyribonuclease 1 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for an hour at 37°C while shaking and digested into a single-cell suspension. The cell suspension was then passed through a 40-μm cell strainer. After the removal of red blood cells by ACK lysis buffer, the cells were resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (500 ml of 1× PBS without Ca2+ or Mg2+ + 2 mM EDTA + 2% FBS) and counted for downstream staining. Live cells (1 × 106) were stained with Zombie Violet live/dead stain (BioLegend) as per the supplier’s recommendations, and excess live/dead stain was removed by washing cells twice and resuspending in 50 μl of FACS buffer. Next, cells were incubated with 1 μg of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (TruStain FcX; BioLegend) on ice for 15 min. The cells were then mixed with 50 μl of mixture of various fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies against murine cell surface markers (table S2) and incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark. Last, cells were rinsed, resuspended in 300 μl of FACS buffer, and was immediately fluorescence activated on LSRII (BD; FACSDiva 8.0.1 software) at the UNC (University of North Carolina) Flow Cytometry Facility. Data were acquired with forward (FSC) and side (SSC) scatter on a linear scale, while fluorescent signals were collected on a five-decade log scale with a minimum of 100,000 events per sample. Nonstained harvested cells were used as universal negative control. Compensation beads (Thermo Fisher) were used for single-color control samples. Harvested spleen cells were used as positive controls for immune cell staining. Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using FCS Express (DeNovo Software). All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend.

Measurement of serum cytokines/chemokines

Analysis of serum cytokines/chemokines was performed using a high-sensitivity immunology multiplex assay kit based on the Luminex platform (Millipore Sigma) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Santos, M. Ross, and A. Valdivia from the ASC for helping with the intravenous/intraperitoneal injections. The flow analysis was performed at the UNC Flow Cytometry Facility, which is supported, in part, by P30 CA016086 Cancer Center Core Support Grant to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. TEM was performed by A. Shankar Kumbhar at the Chapel Hill Analytical and Nanofabrication Laboratory (CHANL), a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), which is supported by the NSF (grant ECCS-1542015) as part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). Multiplex assay was performed by the Animal Histopathology and Laboratory Medicine core–clinical services at the University of North Carolina, which is supported, in part, by an NCI Center Core Support Grant (5P30CA016086-41) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Alliance for Nanotechnology in Cancer (U54CA198999, Carolina Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence). Animal Studies and IVIS imaging were performed within the UNC Lineberger Animal Studies Core (ASC) Facility at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The UNC Lineberger Animal Studies Core is supported, in part, by an NCI Center Core Support Grant (CA16086) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Author contributions: Conceptualization: N.V., D.H., A.V.K., C.V.P., and M.S.-P.; methodology: C.V.P., S.H.A., A.E.D.V.S., N.V., D.H., and E.W.; investigation: N.V., D.H., S.C.F., and E.W.; formal analysis: S.H.A., A.E.D.V.S., C.V.P., N.V., and E.W.; funding acquisition: A.V.K. and C.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation: N.V.; writing—review and editing: C.V.P. and A.V.K.; supervision: C.V.P., A.V.K., and M.S.P. Competing interests: A.V.K. is a co-inventor on patents pertinent to the subject matter of the present contribution, and A.V.K. and M.S.P. have co-founders interest in DelAqua Pharmaceuticals Inc., having intent of commercial development of POx-based drug formulations. A.V.K. is a co-inventor of the U.S. Patent # 9,402,908 B2 and may have certain rights to this invention. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/25/eaba5542/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Chen Z., Fillmore C. M., Hammerman P. S., Kim C. F., Wong K. K., Non-small-cell lung cancers: A heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 535–546 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renaud S., Seitlinger J., Falcoz P. E., Schaeffer M., Voegeli A. C., Legrain M., Beau-Faller M., Massard G., Specific KRAS amino acid substitutions and EGFR mutations predict site-specific recurrence and metastasis following non-small-cell lung cancer surgery. Br. J. Cancer 115, 346–353 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardoll D. M., The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfirschke C., Engblom C., Rickelt S., Zitvogel L., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J., Pfirschke C., Engblom C., Rickelt S., Cortez-retamozo V., Garris C., Pucci F., Yamazaki T., Poirier-colame V., Newton A., Redouane Y., Lin Y., Freeman G. J., Kroemer G., Zitvogel L., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J., Immunogenic chemotherapy sensitizes tumors to article immunogenic chemotherapy sensitizes tumors to checkpoint blockade therapy. Immunity 44, 343–354 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue Y., Osman M., Suda T., Sugimura H., PD-L1 copy number gains: A predictive biomarker for PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy? Transl. Cancer Res. 5, 199–202 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lastwika K. J., Iii W. W., Li Q. K., Norris J., Xu H., Ghazarian S. R., Kitagawa H., Kawabata S., Taube J. M., Yao S., Liu L. N., Gills J. J., Dennis P. A., Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the AKT–mTOR pathway in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2, 227–239 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engblom C., Pfirschke C., Zilionis R., Da J., Martins S., Bos S. A., Courties G., Rickelt S., Severe N., Baryawno N., Faget J., Savova V., Zemmour D., Kline J., Siwicki M., Garris C., Pucci F., Liao H., Lin Y., Newton A., Yaghi O. K., Iwamoto Y., Tricot B., Wojtkiewicz G. R., Nahrendorf M., Cortez-retamozo V., Meylan E., Hynes R. O., Demay M., Klein A., Bredella M. A., Scadden D. T., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J., Osteoblasts remotely supply lung tumors with cancer-promoting SiglecFhigh neutrophils. Science 358, eaal5081 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullis J., Siolas D., Avanzi A., Barui S., Maitra A., Bar-Sagi D., Macropinocytosis of Nab-paclitaxel drives macrophage activation in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 5, 182–191 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zsiros E., Odunsi K., Tumor-associated macrophages: Co-conspirators and orchestrators of immune suppression in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 135, 173–175 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonaventura P., Shekarian T., Alcazer V., Valladeau-guilemond J., Valsesia-Wittmann S., Amigorena S., Caux C., Depil S., Cold tumors: A therapeutic challenge for immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 10, 168 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel A. L., Holt G. E., Lu H., The pharmacokinetics of Toll-like receptor agonists and the impact on the immune system. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 4, 275–289 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smits E. L. J. M., Ponsaerts P., Berneman Z. N., Van Tendeloo V. F. I., The use of TLR7 and TLR8 ligands for the enhancement of cancer immunotherapy. Oncologist 13, 859–875 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagstaff A. J., Perry C. M., Topical imiquimod: A review of its use in the management of anogenital warts, actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinoma and other skin lesions. Drugs 67, 2187–2210 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Z., Wan X., Schulz A., Bludau H., Dobrovolskaia M. A., Stern S. T., Montgomery S. A., Yuan H., Li Z., Alakhova D., Sokolsky M., Darr D. B., Perou C. M., Jordan R., Luxenhofer R., Kabanov A. V., A high capacity polymeric micelle of paclitaxel: Implication of high dose drug therapy to safety and in vivo anti-cancer activity. Biomaterials 101, 296–309 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan X., Beaudoin J. J., Vinod N., Min Y., Makita N., Bludau H., Jordan R., Wang A., Sokolsky M., Kabanov A. V., Co-delivery of paclitaxel and cisplatin in poly(2-oxazoline) polymeric micelles: Implications for drug loading, release, pharmacokinetics and outcome of ovarian and breast cancer treatments. Biomaterials 192, 1–14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi A., Di Maio M., Expert review of anticancer therapy platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: optimal number of treatment cycles. Expert. Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 16, 653–660 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galluzzi L., Senovilla L., Vitale I., Michels J., Martins I., Kepp O., Castedo M., Kroemer G., Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene 31, 1869–1883 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi C.-H., ABC transporters as multidrug resistance mechanisms and the development of chemosensitizers for their reversal. Cancer Cell Int. 5, 30 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zabludoff S. D., Deng C., Grondine M. R., Sheehy A. M., Ashwell S., Caleb B. L., Green S., Haye H. R., Horn C. L., Janetka J. W., Liu D., Mouchet E., Ready S., Rosenthal J. L., Queva C., Schwartz G. K., Taylor K. J., Tse A. N., Walker G. E., White A. M., AZD7762, a novel checkpoint kinase inhibitor, drives checkpoint abrogation and potentiates DNA-targeted therapies. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2955–2966 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang X., Yang Q., Wang W., Liu T., Hu J., VE-822 mediated inhibition of ATR signaling sensitizes chondrosarcoma to cisplatin via reversion of the DNA damage response. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 6083–6092 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chresta C. M., Davies B. R., Hickson I., Harding T., Cosulich S., Critchlow S. E., Vincent J. P., Ellston R., Jones D., Sini P., James D., Howard Z., Dudley P., Hughes G., Smith L., Maguire S., Hummersone M., Malagu K., Menear K., Jenkins R., Jacobsen M., Smith G. C. M., Guichard S., Pass M., AZD8055 is a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor with in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 70, 288–298 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng H., Shcherba M., Pendurti G., Liang Y., Piperdi B., Perez-Soler R., Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: Potential for lung cancer treatment. Lung Cancer Manag. 3, 67–75 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebmann J. E., Cook J. A., Lipschultz C., Teague D., Fisher J., Mitchell J. B., Cytotoxic studies of pacfitaxel (Taxol®) in human tumour cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 68, 1104–1109 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou T. C., Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the chou-talalay method. Cancer Res. 70, 440–446 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scho M., Bong A. B., Drewniok C., Herz J., Geilen C. C., Reifenberger J., Benninghoff B., Slade H. B., Gollnick H., Scho M. P., Tumor-selective induction of apoptosis and the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95, 1138–1149 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu W., Li X., Zhang C., Yang Y., Jiang J., Wu C., Tumor-associated macrophages in cancers. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 18, 251–258 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang Y., Hung M. E., Cangelose B. K., Leonard J. N., Regulation of the IL-10-driven macrophage phenotype under incoherent stimuli. Innate Immun. 22, 647–657 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peine K. J., Gupta G., Brackman D. J., Papenfuss T. L., Ainslie K. M., Satoskar A. R., Bachelder E. M., Liposomal resiquimod for the treatment of leishmania donovani infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 168–175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Sasson S. Z., Wang K., Cohen J., Paul W. E., IL-1β strikingly enhances antigen-driven CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 78, 117–124 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheller J., Chalaris A., Schmidt-arras D., Rose-john S., The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 878–888 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B., Wang X.-Q., Wang X.-Y., Zhang H., Dai W.-B., Wang J., Zhong Z.-L., Wu H.-N., Zhang Q., Nanotoxicity comparison of four amphiphilic polymeric micelles with similar hydrophilic or hydrophobic structure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 10, 47 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodell C. B., Arlauckas S. P., Cuccarese M. F., Garris C. S., Li R., Ahmed M. S., Kohler R. H., Pittet M. J., Weissleder R., TLR7/8-agonist-loaded nanoparticles promote the polarization of tumour-associated macrophages to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 578–588 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrissey K. M., Yuraszeck T. M., Li C. C., Zhang Y., Kasichayanula S., Immunotherapy and novel combinations in oncology: Current landscape, challenges, and opportunities. Clin. Transl. Sci. 9, 89–104 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pecot C. V., Rupaimoole R., Yang D., Akbani R., Ivan C., Lu C., Wu S., Han H., Shah M. Y., Rodriguez-Aguayo C., Bottsford-Miller J., Liu Y., Kim S. B., Unruh A., Gonzalez-Villasana V., Huang L., Zand B., Moreno-Smith M., Mangala L. S., Taylor M., Dalton H. J., Sehgal V., Wen Y., Kang Y., Baggerly K. A., Lee J., Ram P. T., Ravoori M. K., Kundra V., Zhang X., Ali-Fehmi R., Gonzalez-Angulo A.-M., Massion P. P., Calin G. A., Lopez-Berestein G., Zhang W., Sood A. K., Tumour angiogenesis regulation by the miR-200 family. Nat. Commun. 4, 2427 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan X., Min Y., Bludau H., Keith A., Sheiko S. S., Jordan R., Wang A. Z., Sokolsky-Papkov M., Kabanov A. V., Drug combination synergy in worm-like polymeric micelles improves treatment outcome for small cell and non-small cell lung cancer. ACS Nano 12, 2426–2439 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shergold A. L., Millar R., Nibbs R. J. B., Understanding and overcoming the resistance of cancer to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Pharmacol. Res. 145, 104258 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L., Diao L., Yang Y., Yi X., Rodriguez B. L., Li Y., Villalobos P. A., Cascone T., Liu X., Tan L., Lorenzi P. L., Huang A., Zhao Q., Peng D., Fradette J. J., Peng D. H., Ungewiss C., Gay C. M., Fan Y., Class C. A., Zhu J., Rodriguez-canales J., Kawakami M., Byers L. A., Woodman S. E., Vassiliki A., Dmitrovsky E., Wang J., Ullrich S. E., Ignacio I., Heymach J. V., Qin F. X., Gibbons D. L., CD38-mediated immunosuppression as a mechanism of tumor cell escape from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Discov. 8, 1156–1175 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J., Zhang L., Yu C., Yang X.-F., Wang H., Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark. Res. 2, 1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh-Jasuja H., Thiolat A., Ribon M., Boissier M. C., Bessis N., Rammensee H. G., Decker P., The mouse dendritic cell marker CD11c is down-regulated upon cell activation through Toll-like receptor triggering. Immunobiology 218, 28–39 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janssen E. M., Lemmens E. E., Wolfe T., Christen U., Von Herrath M. G., Schoenberger S. P., CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421, 852–856 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vascotto F., Petschenka J., Walzer K. C., Vormehr M., Brkic M., Strobl S., Rösemann R., Diken M., Kreiter S., Türeci Ö., Sahin U., Intravenous delivery of the toll-like receptor 7 agonist SC1 confers tumor control by inducing a CD8+ T cell response. Oncoimmunology 8, 1601480 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doxsee C. L., Riter T. R., Reiter M. J., Gibson S. J., Vasilakos J. P., Kedl R. M., The Immune Response Modifier and Toll-Like Receptor 7 Agonist S-27609 Selectively Induces IL-12 and TNF-α Production in CD11c + CD11b + CD8 − Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 171, 1156–1163 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma J., Larkin J. III, Therapeutic implication of SOCS1 modulation in the treatment of autoimmunity and cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 324 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L., Gibbons D. L., Goswami S., Cortez M. A., Ahn Y.-H., Byers L. A., Zhang X., Yi X., Dwyer D., Lin W., Diao L., Wang J., Roybal J. D., Patel M., Ungewiss C., Peng D., Antonia S., Mediavilla-Varela M., Robertson G., Jones S., Suraokar M., Welsh J. W., Erez B., Wistuba I. I., Chen L., Peng D., Wang S., Ullrich S. E., Heymach J. V., Kurie J. M., Qin F. X.-F., Metastasis is regulated via microRNA-200/ZEB1 axis control of tumour cell PD-L1 expression and intratumoral immunosuppression. Nat. Commun. 5, 5241 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Espinosa E., Márquez-Rodas I., Soria A., Berrocal A., Manzano J. L., Gonzalez-Cao M., Martin-Algarra S.; Spanish Melanoma Group (GEM) , Predictive factors of response to immunotherapy-a review from the Spanish Melanoma Group (GEM). Ann. Transl. Med. 5, 389 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauder D. N., Smith M. H., Senta-McMillian T., Soria I., Meng T. C., Randomized, Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Topical Application of the Immune Response Modulator Resiquimod in Healthy Adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 3846–3852 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dovedi S. J., Melis M. H. M., Wilkinson R. W., Adlard A. L., Stratford I. J., Honeychurch J., Illidge T. M., Systemic delivery of a TLR7 agonist in combination with radiation primes durable antitumor immune responses in mouse models of lymphoma. Blood 121, 251–259 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deguine J., Barton G. M., MyD88: A central player in innate immune signaling. F1000Prime Rep. 6, 97 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto M., Takeda K., Akira S., TIR domain-containing adaptors define the specificity of TLR signaling. Mol. Immunol. 40, 861–868 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothschilds A. M., Wittrup K. D., What, Why, Where, and When: Bringing Timing to Immuno-Oncology. Trends Immunol. 40, 12–21 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schölch S., Rauber C., Tietz A., Rahbari N. N., Bork U., Schmidt T., Kahlert C., Haberkorn U., Tomai M. A., Lipson K. E., Carretero R., Weitz J., Koch M., Huber P. E., Radiotherapy combined with TLR7/8 activation induces strong immune responses against gastrointestinal tumors. Oncotarget 6, 4663–4676 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bugelski P. J., Achuthanandam R., Capocasale R. J., Treacy G., Bouman-Thio E., Monoclonal antibody-induced cytokine-release syndrome. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 5, 499–521 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng L., Zhang Z., Li G., Li F., Wang L., Zhang L., Zurawski S. M., Zurawski G., Levy Y., Su L., Human innate responses and adjuvant activity of TLR ligands in vivo in mice reconstituted with a human immune system. Vaccine 35, 6143–6153 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bird L., Calming the cytokine storm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 417 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norelli M., Camisa B., Barbiera G., Falcone L., Purevdorj A., Genua M., Sanvito F., Ponzoni M., Doglioni C., Cristofori P., Traversari C., Bordignon C., Ciceri F., Ostuni R., Bonini C., Casucci M., Bondanza A., Monocyte-derived IL-1 and IL-6 are differentially required for cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity due to CAR T cells. Nat. Med. 24, 739–748 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natoli G., Ostuni R., Adaptation and memory in immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 20, 783–792 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luxenhofer R., Schulz A., Roques C., Li S., Bronich T. K., Batrakova E. V., Jordan R., Kabanov A. V., Doubly amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline)s as high-capacity delivery systems for hydrophobic drugs. Biomaterials 31, 4972–4979 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dou H., Destache C. J., Morehead J. R., Mosley R. L., Boska M. D., Kingsley J., Gorantla S., Poluektova L., Nelson J. A., Chaubal M., Werling J., Kipp J., Rabinow B. E., Gendelman H. E., Development of a macrophage-based nanoparticle platform for antiretroviral drug delivery. Blood 108, 2827–2835 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pecot C. V., Wu S. Y., Bellister S., Filant J., Rupaimoole R., Hisamatsu T., Bhattacharya R., Maharaj A., Azam S., Rodriguez-Aguayo C., Nagaraja A. S., Morelli M. P., Gharpure K. M., Waugh T. A., Gonzalez-Villasana V., Zand B., Dalton H. J., Kopetz S., Lopez-Berestein G., Ellis L. M., Sood A. K., Therapeutic silencing of KRAS using systemically delivered siRNAs. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 2876–2885 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/25/eaba5542/DC1