Abstract

Data on cause-specific mortality after lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) are lacking. We identified causes of death among 7,289 adults diagnosed with incident first primary LPL (n=3,108) or WM (n=4,181) during 2000–2016 in 17 US population-based cancer registries. Based on 3,132 deaths, 16-year cumulative mortality was 23.2% for lymphomas, 8.4% for non-lymphoma cancers, and 14.7% for non-cancer causes for patients aged <65 years at diagnosis of LPL/WM, versus 33.4, 11.2%, and 48.7%, respectively, for those aged ≥75 years. Compared with the general population, LPL/WM patients had 20% higher risks of death due to non-cancer causes (n=1,341 deaths, standardized mortality ratio [SMR]=1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–1.2), most commonly from infectious (n=188; SMR=1.8; 95%CI, 1.6–2.1), respiratory (n=143; SMR=1.2; 95%CI, 1.0–1.4), and digestive (n=80; SMR=1.8; 95%CI, 1.4–2.2) diseases, but no excess mortality from cardiovascular diseases (n=477, SMR=1.1; 95%CI=1.0–1.1). Risks were highest for non-cancer causes within one year of diagnosis (n=239; SMR<1year=1.3; 95%CI, 1.2–1.5), declining thereafter (n=522; SMR≥5years=1.1; 95%CI, 1.1–1.2). Myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia deaths were notably increased (n=46; SMR=4.4; 95%CI 3.2–5.9), whereas solid neoplasm deaths were only elevated among ≥5-year survivors (n=145; SMR≥5years=1.3; 95% CI=1.1–1.5). This work identifies new areas for optimizing care and reducing mortality for LPL/WM patients.

Introduction

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) are rare, indolent, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) (World Health Organization, 2017). WM, which is distinguished from LPL by the presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) gammopathy (Owen RG, 2003, Swerdlow et al., 2008), can manifest with hyperviscosity syndrome (e.g., visual changes, bleeding, and neurologic dysfunction, including cerebrovascular disease) (Mehta and Singhal, 2003) or symptomatic tissue deposition (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, amyloidosis, renal dysfunction, and gastrointestinal malabsorption) (Dimopoulos et al., 2000). Alternatively, WM/LPL may be asymptomatic or present with findings including cytopenias, B symptoms (i.e., fevers, night sweats, weight loss), or adenopathy. Symptomatic individuals are typically considered for treatment with chemotherapy (Leblond et al., 2016). Evolving treatment approaches with alkylating agents (e.g., chlorambucil), nucleoside analogs (e.g., fludarabine, cladribine), rituximab (alone or in combination), and newer targeted therapies (e.g., ibrutinib, bortezomib) (Gertz, 2015) have substantially improved survival (Olszewski et al., 2017, Castillo et al., 2014). Studying cause-specific mortality can identify high-risk patients, latency patterns, and potentially preventable causes of death, which may inform priority areas for the allocation of healthcare resources.

The current understanding of mortality among LPL/WM patients is limited, based on clinical series with small case numbers (García-Sanz et al., 2001, Kastritis et al., 2015) and/or studies with little detail about cause-specific mortality (Castillo et al., 2015b). While significant mortality is attributed to conditions other than LPL/WM, (Castillo et al., 2015b, García-Sanz et al., 2001) deaths due to non-cancer conditions and cancers other than lymphomas are poorly characterized. Cardiovascular, infectious, and neurologic conditions have been identified as the most common non-cancer causes of death, (Castillo et al., 2015b, García-Sanz et al., 2001, Kastritis et al., 2015) but these risks have not been quantified compared to the general population, and information on more specific and other causes of death is sparse. Data are lacking on mortality patterns for LPL versus WM patients, which could differ due to the presence of IgM gammopathy, and for other factors associated with developing LPL/WM, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Nipp et al., 2014, Giordano et al., 2009), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Gibson et al., 2014, Koshiol et al., 2008), or respiratory tract infections (McShane et al., 2014, Kristinsson et al., 2010).

We leveraged United States (US) population-based data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, identifying 7,289 LPL/WM patients diagnosed during 2000–2016 who had long-term, systematic follow-up, enabling us to conduct the first comprehensive investigation of cause-specific and excess mortality for LPL/WM patients compared to the general US population.

Methods

Study Population and Patient Data

All incident first primary LPL/WM cases diagnosed during 2000–2016 within 17 SEER registry areas were identified based on International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) morphology codes (LPL: 9671; WM: 9761) (Fritz et al., 2013). The study period is coincident with the expansion of SEER to include 17 SEER registry areas covering over one-quarter of the US population (Howlader et al., 2019) and the introduction of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, which classifies WM and LPL jointly as mature B-cell neoplasms versus earlier designation of WM as a non-malignant entity (Jaffe et al., 2001). SEER data include patient demographic characteristics, date and type of cancer diagnoses, and type of initial therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Detailed clinical data, names of specific chemotherapeutic agents, and receipt of subsequent therapy administered at disease progression/relapse are not available from SEER registries.

In the US, cause of death is compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) using an algorithm that identifies the underlying cause of death (the disease or injury that initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury) according to World Health Organization (WHO) regulations (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/). SEER reports this underlying cause of death information, which has been classified according to the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) since 1999. Guided by ICD-10 codes (http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2004/fr-icd.htm?kf00.htm) and the SEER Cause of Death Recode (https://seer.cancer.gov/codrecode/1969_d03012018/index.html), we categorized deaths broadly as due to lymphomas, non-lymphoma cancers, non-cancer conditions, or unknown causes if no cause of death was reported on the death certificate (Table S1). Due to possible misclassification of lymphoma-related deaths on death certificates (Mieno et al., 2016, Deckert, 2016), we broadly defined lymphoma deaths to include all lymphomas (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin), paraproteinemias (e.g., monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, amyloidosis, and plasma cell malignancies), and lymphocytic leukemias. We further subdivided non-lymphoma cancer causes of death (hereafter referred to as “non-lymphoma cancers”) into solid cancers, classified by organ system, or non-lymphoma hematologic cancers. Non-cancer causes of death (hereafter referred to as “non-cancer conditions”) were defined by organ system.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were followed from the time of LPL/WM diagnosis until death, loss to follow-up, or end of study (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. As an absolute measure of mortality, we estimated cumulative mortality for lymphomas, non-lymphoma cancers, and non-cancer conditions, accounting for competing risks of death for up to 16 years following LPL/WM diagnosis (SAS version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) (Gooley et al., 1999). We then estimated risks of death overall and due to specific causes compared with the general population. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs), calculated as the ratio of observed versus expected (O/E) number of cases for a given cause of death category, estimated the relative risk of death compared with the general population. The expected number of cases for specific causes of death were calculated using US mortality rates (Howlader et al., 2019) for the general population stratified by age (5-year groups), race (white/unknown, black, other), sex (male, female) and year of death (5-year groups), multiplied by the appropriate person-years at risk. Corresponding exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the SMRs were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution (Breslow and Day, 1987). We estimated excess absolute risk (EAR) of death per 10,000 person-years [EAR=10,000 × (observed - expected)/person-years)]. SMRs, 95%CIs, and EARs were calculated using SEER*Stat software version 8.3.5 (Surveillance Research Program).

Since LPL and WM have similar survival (Castillo et al., 2014), are often studied together, and are considered highly-related neoplasms by the WHO classification (Harris et al., 1994, Jaffe et al., 2001, Owen RG, 2003, Treon et al., 2003, Swerdlow et al., 2008), our primary analyses focused on the overall combined cohort of LPL/WM patients, with further analyses by patient subgroups defined by age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and receipt of initial chemotherapy. We conducted a secondary analysis comparing SMRs for LPL and WM separately to assess for potential differences in mortality patterns. For cause of death categories with ≥25 observed deaths in the total population, we constructed multivariable Poisson regression models stratified by sex, lymphoma subtype (LPL versus WM), receipt of initial chemotherapy, age at diagnosis, and time since diagnosis to test for statistically significant (P<0.05) heterogeneity of the SMRs between patient subgroups using the AMFIT module of Epicure (Preston et al., 2015), software version 2.0. P values were calculated using likelihood ratio tests, comparing model fit with and without the variable of interest.

Results

The study cohort of 7,289 patients with first primary LPL/WM (3,108 LPL; 4,181 WM) was predominantly male (58.5%) and white/unknown (89.4%) (Table 1), with a mean age at LPL/WM diagnosis of 69.7 years. Slightly fewer than half (44.0%) of LPL/WM patients were reported to SEER as having received initial chemotherapy, and only 2.3% of patients received any initial radiotherapy. In total, 43.0% (n=3,132) LPL/WM patients died during the study period (mean follow-up=5.2 years). Patient cases and deaths were distributed disproportionately by age, with patients ≥75 years at diagnosis accounting for 36.8% of cases but 54.8% of deaths. Most (64.5%) deaths occurred <5 years following LPL/WM diagnosis, with 23.1% occurring within one year of diagnosis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for 7,289 individuals diagnosed with LPL/WM, 17 SEER registry areas, 2000 – 2016*

| LPL and WM Combined | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons | Person-Years | Deaths | |||

| Patient Characteristics (n=7,289) | N | % | N | N | % |

| Total | 7,289 | 100.0 | 38,032 | 3,132 | 100.0 |

| LPL | 3,108 | 42.6 | 15,543 | 1,346 | 43.0 |

| WM | 4,181 | 57.4 | 22,489 | 1,786 | 57.0 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 4,266 | 58.5 | 21,936 | 1,892 | 60.4 |

| Female | 3,023 | 41.5 | 16,096 | 1,240 | 39.6 |

| Race | |||||

| White/Unknown† | 6,518 | 89.4 | 34,337 | 2,807 | 89.6 |

| Black | 385 | 5.3 | 1,888 | 174 | 5.6 |

| Other | 386 | 5.3 | 1,807 | 151 | 4.8 |

| Initial chemotherapy | |||||

| No known chemotherapy | 4,079 | 56.0 | 21,233 | 1,692 | 54.0 |

| Known chemotherapy | 3,210 | 44.0 | 16,799 | 1,440 | 46.0 |

| Age at diagnosis | |||||

| < 65 years | 2,498 | 34.3 | 16,554 | 629 | 20.1 |

| 65 to 74 years | 2,111 | 29.0 | 11,012 | 788 | 25.2 |

| ≥ 75 years | 2,680 | 36.8 | 10,466 | 1,715 | 54.8 |

| Time since LPL/WM diagnosis‡ | |||||

| < 1 year | 7,289 | 100.0 | 6,497 | 725 | 23.1 |

| 1 to < 5 years | 5,960 | 81.8 | 17,784 | 1,297 | 41.4 |

| ≥ 5 years | 3,206 | 44.0 | 13,751 | 1,110 | 35.4 |

Abbreviations: LPL: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma N: Number; SEER 17: 17 cancer registry areas of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, and Greater California; Connecticut; Detroit, Michigan; Atlanta, Greater Georgia, and Rural Georgia; Hawaii; Iowa; Kentucky; Louisiana; New Mexico; New Jersey; Seattle-Puget Sound, Washington; and Utah); WM: Waldenström macroglobulinemia; %: percentage.

Whites account for 87.6% (n=6,388) of persons, 33,699 person-years, and 89.4% (n=2,799) of deaths, whereas people of unknown race account for 1.8% (n=130) of persons, 638 person-years, and 0.3% (n=8) of deaths.

The number of individuals entering a specified period includes only those who are alive and have survived the required amount of time. Individuals are censored at the time of death (dead), or at the time when follow-up ends (alive). For example, individuals entering the <1-year interval who are alive and have survived 8 months since LPL/WM diagnosis, enter the <1-year interval but are censored at 8 months (alive), and do not enter the 1- to <5-year interval. An analogous situation occurs in the ≥5-year interval, and individuals who survive 1-year but have not yet survived 5-years, are censored (alive) within the 1- to <5-year interval and do not enter the ≥5-year interval.

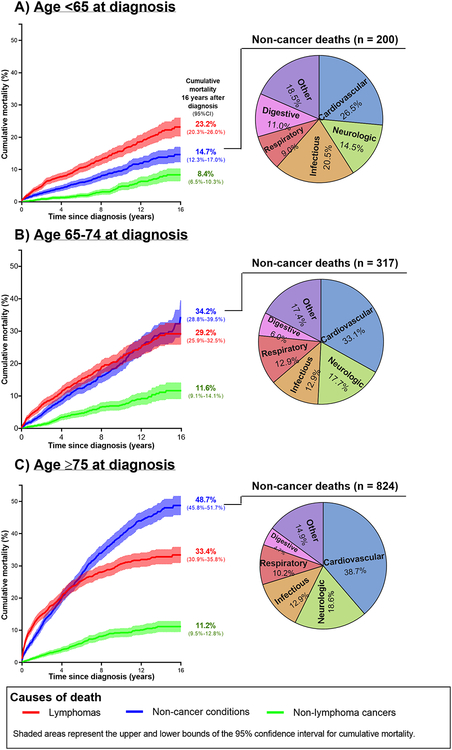

Cumulative Mortality

Most deaths were attributable to lymphomas (n=1,342, 42.8%) or non-cancer conditions (n=1,341, 42.8%), with many fewer deaths attributable to non-lymphoma cancers (n=397, 12.7%) or unknown causes (n=52, 1.7%). Patterns of cumulative mortality varied by age at diagnosis, particularly for non-cancer conditions (Figure 1). In those aged <65 years at LPL/WM diagnosis, lymphoma deaths predominated, reaching 23.2% (95%CI, 20.3%−26.0%) at 16 years after LPL/WM, compared to 14.7% (95%CI, 12.3%−17.0%) for non-cancer conditions and 8.4% (95%CI, 6.5%−10.3%) and for non-lymphoma cancers. In patients aged 65–74 at diagnosis, cumulative mortality was of comparable magnitude for lymphomas and non-cancer conditions. However, among the oldest patients (≥75 years at diagnosis), lymphoma deaths rose quickly within one year after diagnosis, while non-cancer deaths surpassed lymphoma deaths at 4.7 years after LPL/WM. By 16 years after LPL/WM, cumulative mortality for patients aged ≥75 years at diagnosis reached 33.4% (95%CI, 30.9%−35.8%) for lymphomas and 48.7% (95%CI, 45.8%−51.7%) for non-cancer conditions, whereas deaths due to non-lymphoma cancers remained relatively low, similar to other age groups. The most common non-cancer causes of death were cardiovascular (n=477), neurologic (n=238), infectious (n=188), respiratory (n=143), and digestive (n=80) diseases, with slight differences in the distribution by age at LPL/WM diagnosis. The most common non-lymphoma cancers were lung (n=92) and colorectal (n=32) cancers and myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) (n=46).

Figure 1:

Cumulative mortality for LPL/WM patients by time since diagnosis and distribution of non-cancer deaths, stratified by age

Cause-Specific Mortality Risks

Overall, LPL/WM patients had a 20% higher risk of death due to non-cancer causes compared to the general population (n=1,341, SMR=1.2; 95%CI, 1.1–1.2; EAR 46.8) (Table 2). Among the most common non-cancer causes of death, only infectious (SMR=1.8; 95%CI, 1.6–2.1), respiratory (SMR=1.2; 95%CI, 1.0–1.4), and digestive (SMR=1.8; 95%CI, 1.4–2.2) diseases occurred at a higher rate than expected in the general population, with infections accounting for the greatest excess risk of death (EAR=22.6). In contrast, neurologic deaths occurred statistically significantly less often than expected (SMR=0.9; 95%CI, 0.8–1.0), and mortality due to all types of cardiovascular disease combined was comparable with the general population (n=477; SMR=1.1; 95%CI=1.0–1.1), although risk was elevated for atherosclerosis specifically (n=15; SMR=2.5; 95%CI, 1.4–4.2). Other less common conditions with statistically significantly increased risks included benign hematologic (n=39; SMR=7.4; 95%CI, 5.2–10.1) and rheumatologic (n=8; SMR=2.5; 95%CI, 1.1–5.0) diseases, the former accounting for a higher excess absolute risk (EAR=8.9) than for respiratory diseases (EAR=6.1).

Table 2.

Cause-specific risks of death among LPL/WM patients, 17 SEER registry areas, 2000 – 2016*

| LPL and WM Combined | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of Death | N | SMR | (95% CI) | EAR |

| Non-cancer conditions | 1,341 | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.2) | 46.8 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 477 | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | 5.5 |

| Heart diseases | 430 | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) | 3.3 |

| Hypertension without heart disease | 21 | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.9) | 1.0 |

| Atherosclerosis | 15 | 2.5 | (1.4, 4.2) | 2.4 |

| Neurologic diseases | 238 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | −10.2 |

| Dementia | 105 | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | −10.3 |

| Alzheimer disease | 50 | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.0) | −3.9 |

| Vascular dementia | 6 | 0.8 | (0.3, 1.7) | −0.5 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 85 | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.2) | −1.7 |

| Infectious diseases | 188 | 1.8 | (1.6, 2.1) | 22.6 |

| Septicemia | 30 | 1.4 | (0.9, 2.0) | 2.3 |

| HIV | 11 | 11.3 | (5.7, 20.3) | 2.6 |

| Mycoses and protozoal infections | 5 | 9.3 | (3.0, 21.7) | 1.2 |

| Respiratory infections | 88 | 1.6 | (1.3, 2.0) | 8.7 |

| Pneumonia and influenza | 61 | 1.5 | (1.2, 2.0) | 5.6 |

| Pneumonitis and aspiration | 22 | 1.5 | (0.9, 2.3) | 1.9 |

| Gastrointestinal infections | 36 | 3.6 | (2.5, 5.0) | 6.8 |

| Viral hepatitis | 14 | 6.9 | (3.8, 11.7) | 3.2 |

| Intestinal infections | 22 | 2.8 | (1.7, 4.2) | 3.7 |

| Clostridium difficile enterocolitis | 15 | 3.2 | (1.8, 5.2) | 2.7 |

| Respiratory diseases | 143 | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 6.1 |

| COPD and associated pulmonary diseases | 115 | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 4.5 |

| Interstitial lung diseases | 18 | 1.4 | (0.8, 2.2) | 1.3 |

| Digestive diseases | 80 | 1.8 | (1.4, 2.2) | 9.2 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 14 | 1.9 | (1.0, 3.2) | 1.7 |

| Stomach and duodenal ulcers | 5 | 2.5 | (0.8, 5.9) | 0.8 |

| Liver diseases | 32 | 2.1 | (1.4, 2.9) | 4.4 |

| Chronic liver diseases | 26 | 2.3 | (1.5, 3.4) | 3.9 |

| Diseases of intestine or colon | 22 | 1.6 | (1.0, 2.4) | 2.2 |

| Vascular diseases of intestine or colon | 12 | 2.4 | (1.2, 4.1) | 1.8 |

| Nonvascular diseases of intestine or colon | 10 | 1.2 | (0.6, 2.1) | 0.4 |

| Accidents, falls, and adverse events | 51 | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.6) | 2.3 |

| Endocrine diseases | 50 | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.1) | −2.5 |

| Diabetes | 31 | 0.7 | (0.5, 1.1) | −2.8 |

| Renal diseases | 42 | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.7) | 2.3 |

| Nephritic/nephrotic diseases | 40 | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.8) | 2.3 |

| Benign hematologic diseases | 39 | 7.4 | (5.2, 10.1) | 8.9 |

| Non-immune cytopenias | 22 | 6.5 | (4.1, 9.8) | 4.9 |

| Immune cytopenias | 5 | 21.7 | (7.1, 50.7) | 1.3 |

| Immune dysregulation | 8 | 17.5 | (7.6, 34.5) | 2.0 |

| Rheumatologic diseases | 8 | 2.5 | (1.1, 5.0) | 1.3 |

| Non-lymphoma cancers | 397 | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.4) | 22.8 |

| Solid cancers | 313 | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) | 5.1 |

| Digestive tract | 79 | 1.0 | (0.8, 1.2) | −0.4 |

| Esophagus | 11 | 1.3 | (0.7, 2.3) | 0.7 |

| Colorectal | 32 | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.5 |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 11 | 1.0 | (0.5, 1.9) | 0.1 |

| Pancreas | 16 | 0.8 | (0.4, 1.3) | −1.3 |

| Lung | 92 | 1.0 | (0.8, 1.2) | 0.2 |

| Melanoma | 6 | 1.2 | (0.4, 2.6) | 0.2 |

| Breast | 9 | 0.6 | (0.3, 1.2) | −1.5 |

| Ovary | 10 | 1.8 | (0.9, 3.3) | 1.2 |

| Prostate | 13 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.8) | −3.6 |

| Urinary tract | 19 | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.5) | −0.3 |

| Brain and central nervous system | 15 | 2.4 | (1.3, 4.0) | 2.3 |

| MDS/AML | 46 | 4.4 | (3.2, 5.9) | 9.4 |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | 6 | 3.3 | (1.2, 7.1) | 1.1 |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Specific disease categories with at least 5 deaths are included in this table, except “all causes of death” (n=3,132), “lymphomas” (n=1,342), “non-melanoma skin cancers” (n=12), and “unknown causes” (n = 52). Non-specific categories of death are excluded from this table.

Bolded SMRs and 95% CI values indicate statistically significant (P<0.05) values, e.g., unrounded CI excludes 1.00.

Abbreviations: AML: acute myeloid leukemia; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EAR: excess absolute risk; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; LPL: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; N: observed number of deaths; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SMR: standardized mortality ratio; WM: Waldenström macroglobulinemia; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Cause of Death Categories are based on SEER Cause of Death Recode 1969+. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/codrecode/1969_d03012018/index.html.

Individuals diagnosed with LPL/WM had statistically significantly elevated risks of death due to several infections, with the highest SMRs (>5) for HIV, mycoses/protozoal infections, and viral hepatitis, albeit based on small numbers. Among deaths due to digestive diseases, SMRs were statistically significantly (>1.5) increased for gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic liver diseases, and vascular diseases of intestine/colon. For benign hematologic diseases, SMRs were more than >15-fold increased for immune cytopenias and immune dysregulation, the latter of which includes immunodeficiencies and disorders involving lymphoreticular or reticulohistiocytic tissues.

Overall, non-lymphoma cancer deaths were 30% increased compared to the general population (n=397, SMR=1.3; 95%CI, 1.2–1.4) and primarily driven by >2-fold increased SMRs for MDS/AML, myeloproliferative neoplasms, and brain and central nervous system (brain/CNS) cancers.

Patient Subgroups

Notable differences were observed by age at LPL/WM diagnosis, for which SMRs generally declined with increasing age for non-cancer conditions and non-lymphoma cancers (Table 3, Table S2). Large differences by age were observed for neurologic diseases, particularly cerebrovascular diseases (SMR<65=2.0, SMR65–74=1.2, SMR≥75=0.8), and respiratory infections, specifically pneumonia/influenza (SMR<65=4.2, SMR65–74=1.4, SMR≥75=1.3). A notable exception was for gastrointestinal infections, particularly viral hepatitis, with highest risks for older patients (SMR<65=4.4, SMR65–74=6.4, SMR≥75=14.9).

Table 3.

Cause-specific risks of death among LPL/WM patients by age at diagnosis, 17 SEER registry areas, 2000 – 2016*

| < 65 years old | 65–74 years old | ≥ 75 years old | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of Death | N | SMR | (95% CI) | N | SMR | (95% CI) | N | SMR | (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity |

| Non-cancer conditions | 200 | 1.6 | (1.4, 1.9) | 317 | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.4) | 824 | 1.0 | (1.0, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Heart diseases | 51 | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.6) | 94 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.3) | 285 | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) | 0.252 |

| Neurologic diseases | 29 | 2.0 | (1.3, 2.9) | 56 | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.5) | 153 | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 5 | 1.8 | (0.6, 4.1) | 18 | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.5) | 82 | 0.7 | (0.5, 0.8) | 0.316 |

| Alzheimer disease | <3 | ~ | ~ | 8 | 0.9 | (0.4, 1.7) | 40 | 0.7 | (0.5, 1.0) | 0.645 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 14 | 2.0 | (1.1, 3.4) | 21 | 1.2 | (0.7, 1.8) | 50 | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.0) | 0.006 |

| Infectious diseases | 41 | 3.9 | (2.8, 5.3) | 41 | 2.0 | (1.4, 2.7) | 106 | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Septicemia | 5 | 1.8 | (0.6, 4.2) | 10 | 1.9 | (0.9, 3.4) | 15 | 1.1 | (0.6, 1.9) | 0.423 |

| Respiratory infections | 15 | 4.1 | (2.3, 6.8) | 17 | 1.8 | (1.0, 2.8) | 56 | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.7) | 0.004 |

| Pneumonia and influenza | 11 | 4.2 | (2.1, 7.5) | 10 | 1.4 | (0.7, 2.6) | 40 | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.8) | 0.021 |

| Gastrointestinal infections | 7 | 3.7 | (1.5, 7.7) | 5 | 2.2 | (0.7, 5.1) | 24 | 4.1 | (2.7, 6.2) | 0.368 |

| COPD and associated pulmonary diseases | 13 | 1.2 | (0.6, 2.0) | 35 | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.7) | 67 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.5) | 0.893 |

| Digestive diseases | 22 | 2.4 | (1.5, 3.7) | 19 | 1.7 | (1.0, 2.6) | 39 | 1.6 | (1.1, 2.2) | 0.172 |

| Liver diseases | 14 | 2.3 | (1.3, 3.9) | 8 | 1.7 | (0.7, 3.3) | 10 | 2.2 | (1.1, 4.1) | 0.650 |

| Chronic liver diseases | 12 | 2.6 | (1.3, 4.5) | 8 | 2.3 | (1.0, 4.5) | 6 | 2.0 | (0.7, 4.3) | 0.675 |

| Accidents, falls, and adverse events | 12 | 1.3 | (0.7, 2.3) | 10 | 1.1 | (0.5, 2.1) | 29 | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.7) | 0.957 |

| Endocrine diseases | 5 | 0.5 | (0.2, 1.3) | 15 | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.6) | 30 | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.2) | 0.474 |

| Diabetes | <3 | ~ | ~ | 9 | 0.8 | (0.4, 1.5) | 20 | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.3) | 0.327 |

| Nephritic/nephrotic diseases | 4 | 1.3 | (0.4, 3.4) | 12 | 1.7 | (0.9, 3.0) | 24 | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.7) | 0.265 |

| Benign hematologic diseases | 9 | 13.0 | (6.0, 24.7) | 7 | 5.9 | (2.4, 12.1) | 23 | 6.8 | (4.3, 10.1) | 0.244 |

| Non-lymphoma cancers | 94 | 1.6 | (1.3, 1.9) | 116 | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 187 | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.4) | 0.291 |

| Solid cancers | 75 | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.6) | 89 | 1.0 | (0.8, 1.2) | 149 | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.2) | 0.282 |

| Digestive tract | 18 | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.7) | 21 | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.3) | 40 | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.4) | 0.639 |

| Colorectal | 3 | 0.6 | (0.1, 1.7) | 8 | 0.9 | (0.4, 1.9) | 21 | 1.3 | (0.8, 2.0) | 0.168 |

| Lung | 26 | 1.3 | (0.9, 2.0) | 28 | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.2) | 38 | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.3) | 0.337 |

| MDS/AML | 10 | 7.6 | (3.7, 14.0) | 18 | 5.9 | (3.5, 9.3) | 18 | 3.0 | (1.8, 4.7) | 0.160 |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Specific disease categories with at least 25 deaths among all individuals with LPL/WM are included in this table, except “all causes of death,” “lymphomas,” and “unknown causes.” Non-specific categories of death are excluded. Among non-cancer conditions, if a subcategory comprised >75% of total deaths of its overarching category, only the subcategory is included in this table.

Bolded SMR, 95% CI, and Pheterogeneity values indicate statistically significant (P<0.05) values, e.g., unrounded CI excludes 1.00. Pheterogeneity values are based on a multivariate Poisson regression model, stratified by sex, lymphoma subtype (LPL versus WM), receipt of initial chemotherapy, and time since diagnosis.

Abbreviations are explained in Table 2; ~: SIR and 95% CI not shown for <3 cases to protect patient confidentiality.

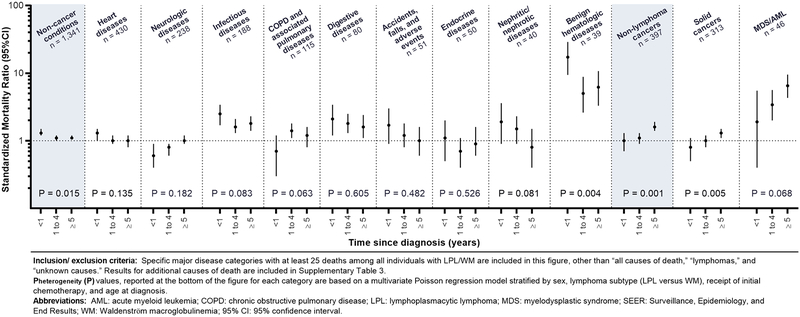

Non-cancer mortality risks were highest in the first year after LPL/WM, with 17.8% of non-cancer deaths occurring within one year (SMR<1year=1.3, SMR1–4years=1.1 SMR≥5years=1.1, Phomogeneity=0.015; Table S3). This pattern was most striking for benign hematologic diseases (SMR<1year=17.2, SMR1–4years=5.0, SMR≥5years=6.2) but was consistent among most non-cancer causes of death (Figure 2). The main exception was for dementia deaths, which occurred at lower rates than observed in the population until ≥5 years after diagnosis (SMR≥5years=1.0). SMRs for deaths due to solid cancers increased with time since diagnosis, particularly for lung (SMR<1year=0.3, SMR1–4years=1.2, SMR≥5years=1.2) and colorectal (SMR<1year=0.8, SMR1–4years=0.7, SMR≥5years=1.6) cancers. Notably, the SMR for MDS/AML was highest among ≥5-year survivors (SMR<1year=1.9, SMR1–4years=3.4, SMR≥5years=6.5), although the differences in risk by time since LPL/WM were not statistically significant.

Figure 2:

Cause-specific risks of death among LPL/WM patients by time since diagnosis, 17 SEER registries, 2000–2016

SMRs generally did not differ based on receipt of initial chemotherapy (Table S4). Exceptions to this finding included higher risks of death due to adverse events/falls/accidents or MDS/AML and lower risks of death due to diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease among those who received initial chemotherapy. Risks of death for LPL and WM patients, compared to the general population, were largely similar (Table S5).

Discussion

In the largest population-based mortality study of LPL/WM to date and the first to compare rates with the US general population, we comprehensively assessed patterns of mortality among patients diagnosed during 2000–2016. LPL/WM patients had notably elevated non-cancer mortality risks, particularly within 1 year of diagnosis. Infectious, respiratory, digestive, and benign and malignant hematologic conditions posed elevated mortality risks, whereas solid cancer and cardiovascular deaths generally occurred at similar rates to the general population during follow-up of 16 years or less. The majority of deaths were attributable to causes other than lymphoma, especially non-cancer conditions and particularly among older patients. Age at and time since diagnosis significantly impacted mortality risks, but patterns were generally similar for LPL and WM.

Prior LPL/WM mortality studies have reported the important contribution of non-lymphoma deaths, particularly among older patients, but have not quantified cause-specific risks (Kastritis et al., 2015, García-Sanz et al., 2001, Castillo et al., 2015b). Our study confirms that cardiovascular diseases, neurologic diseases, and infections were the most common non-cancer deaths in LPL/WM patients, but is the first investigation to report that infectious deaths as well as respiratory, digestive, and benign hematologic disease deaths occurred at an increased rate. However, no elevated risks of death were observed for cardiovascular and neurologic diseases. While lymphomas accounted for a substantial number of deaths, the higher proportion of lymphoma-related deaths (~43% versus ~25%) in our study compared with a previous SEER report (Castillo et al., 2015b) likely reflects our recategorization of the ICD-10 code for WM from the “unknown” category into the category of lymphoma deaths and inclusion of potentially misclassified diseases (e.g., lymphocytic leukemias) within this category.

We observed increased mortality risks for certain infections (Clostridium difficile enterocolitis, mycoses/protozoal infections, viral hepatitis, HIV, and respiratory tract infections) and specific digestive diseases (chronic liver diseases, gastrointestinal bleeding, and vascular diseases of the intestine and colon). Previous studies have reported that viral hepatitis, HIV, and respiratory tract infections are rare but important risk factors for LPL/WM, which could account for increased mortality due to these infections (Koshiol et al., 2008, Vajdic et al., 2014, Giordano et al., 2009, Nipp et al., 2014, Gibson et al., 2014, Kristinsson et al., 2010, McShane et al., 2014). Additional factors that may have contributed to increased risk of infection-related mortality include long-term disease and treatment-related immunosuppression (Karlsson et al., 2011, Olszewski et al., 2017, Caplan et al., 2017, Narum et al., 2014, Hernández-Díaz and García Rodríguez, 2001, Rao and Faso, 2012), recurrent/increased antimicrobial and corticosteroid use and/or exposure to healthcare settings (particularly for Clostridium difficile enterocolitis and mycoses/protozoal infections) (Revolinski and Munoz-Price, 2018, Varughese et al., 2018), and chemotherapy use leading to hepatitis virus reactivation (Yeo et al., 2000, European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2017). Infection-related mortality should continue to be monitored with increasing use of bendamustine and ibrutinib, which are associated with pneumonia, fungal, and other clinically significant infections (Olszewski et al., 2018, Varughese et al., 2018, Fung et al., 2019, Cheng et al., 2019, Fillatre et al., 2014).

In contrast to infections, cardiovascular and neurologic diseases—the other most common non-cancer deaths in LPL/WM patients (Castillo et al., 2015b)—posed no overall increased risk of mortality compared to the general population. The borderline but not significantly elevated mortality risk (SMR=1.1) from cardiovascular diseases after LPL/WM contrasts with strikingly increased cardiovascular mortality risks among patients with other NHLs and solid cancers, (Abuamsha et al., 2019, Sturgeon et al., 2019) possibly reflecting lower use of cardiotoxic agents and radiotherapy in LPL/WM. Decreased risks of neurologic deaths may be due to underreporting of dementia as an underlying cause of death (Macera et al., 1992, Romero et al., 2014, Ganguli and Rodriguez, 1999, Ives et al., 2009), although the novel finding of elevated risk of death due to cerebrovascular diseases exclusively in patients aged <65 at LPL/WM correlates with the higher observed rates of symptomatic hyperviscosity among younger WM patients (Bustoros et al., 2019).

This first report of mortality due to non-lymphoma cancers highlights elevated risks for MDS/AML but no overall elevations due to solid tumors combined. Increased mortality risks due to MDS/AML, particularly in patients who received initial chemotherapy, are consistent with the use of leukemogenic agents for LPL/WM (Leleu et al., 2009, Leblond et al., 2013). Some, but not all, studies evaluating second cancer incidence, including large SEER-based studies, have suggested 20–40% elevated incidence rates for solid cancers overall and specific increases for colorectal, thyroid, urinary tract, melanoma, lung, and brain/CNS cancers (Ojha and Thertulien, 2012, Castillo et al., 2015a, Morra et al., 2013, Varettoni et al., 2012, Castillo and Gertz, 2017). Differences between second cancer incidence and mortality results may reflect the favorable prognosis or early detection associated with some cancers. For example, LPL/WM staging-related imaging and greater patient interaction with the health care system may contribute to early detection and subsequently decreased lung and prostate cancer mortality observed within the first year(s) after LPL/WM diagnosis (Kastritis et al., 2018, Castillo et al., 2015c, Varettoni et al., 2012, Ojha and Thertulien, 2012, Castillo et al., 2015a, Howlader et al., 2019). Notably, deaths due to colorectal cancers were not increased, contrasting with a prior report suggesting LPL/WM patients may develop more aggressive second incident colorectal cancers or be unfit to receive appropriate colorectal cancer therapy (Castillo et al., 2015c). Brain/CNS tumors were the only solid tumors with an overall significantly elevated risk of death, possibly related to their poor prognosis (Howlader et al., 2019), though it is not known why brain/CNS tumors are more common after LPL/WM.

Strengths of our population-based study include the large number of LPL/WM patients diagnosed and treated throughout the US during a recent time period with systematic follow-up. We identified specific causes of death based on death certificates for >98% of patients. Study limitations include the lack of information on patient comorbidities, potential cause of death misclassification, underascertainment of initial chemotherapy, and lack of detailed clinical data on specific chemotherapeutic agents. Additionally, we lacked information to systematically assess mortality due to transformation events in indolent lymphomas because the majority of lymphoma deaths are coded without subtype-specific information (Castillo et al., 2015a, Morra et al., 2013).

Our study substantially furthers the understanding of specific conditions that have the greatest potential to be life-limiting for LPL/WM patients in the current era. These findings provide a framework for optimizing follow-up care strategies based on patient age and time since diagnosis. In particular, non-cancer conditions result in excess mortality, especially within the first year after diagnosis, and should be an area of increased clinical focus. Among older individuals, mortality due to non-cancer conditions and non-lymphoma cancers surpassed mortality due to lymphomas, suggesting that early recognition and interventions with therapeutic and supportive measures may favorably impact mortality risks. Furthermore, despite IgM gammopathy in WM, mortality did not vary significantly between LPL and WM patients, suggesting that interventions to reduce mortality may be implemented similarly for LPL and WM. Future research encompassing information on comorbid conditions, more specific causes of death, detailed clinical and chemotherapy data, and increased follow-up to identify longer-term risks will further our understanding of mortality after LPL/WM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH); the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF Grant # 2014194), Genentech, Elsevier, and other private donors. The authors thank Jeremy Miller (Information Management Services (IMS), Inc) for his analytical support and Ruth Pfeiffer, PhD, for helpful discussions on cumulative mortality. This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent FDA’s view or policies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to this topic.

References

- ABUAMSHA H, KADRI AN & HERNANDEZ AV 2019. Cardiovascular mortality among patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Differences according to lymphoma subtype. Hematological Oncology, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRESLOW NE & DAY NE 1987. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II - the design and analysis of cohort studies., IARC Scientific Publications. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSTOROS M, SKLAVENITIS-PISTOFIDIS R, KAPOOR P, LIU CJ, KASTRITIS E, ZANWAR S, FELL G, ABEYKOON JP, HORNBURG K, NEUSE CJ, MARINAC CR, LIU D, SOIFFER J, GAVRIATOPOULOU M, BOEHNER C, CAPPUCCIO J, DUMKE H, REYES K, SOIFFER RJ, KYLE RA, TREON SP, CASTILLO JJ, DIMOPOULOS MA, ANSELL SM, TRIPPA L & GHOBRIAL IM 2019. Progression Risk Stratification of Asymptomatic Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1403–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPLAN A, FETT N, ROSENBACH M, WERTH VP & MICHELETTI RG 2017. Prevention and management of glucocorticoid-induced side effects: A comprehensive review: Gastrointestinal and endocrinologic side effects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 76, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILLO JJ & GERTZ MA 2017. Secondary malignancies in patients with multiple myeloma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 58, 773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILLO JJ, OLSZEWSKI AJ, CRONIN AM, HUNTER ZR & TREON SP 2014. Survival trends in Waldenström macroglobulinemia: an analysis of the Surveillance,Epidemiology and End Results database. Blood. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILLO JJ, OLSZEWSKI AJ, HUNTER ZR, KANAN S, MEID K & TREON SP 2015a. Incidence of secondary malignancies among patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: An analysis of the SEER database. Cancer, 121, 2230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILLO JJ, OLSZEWSKI AJ, KANAN S, MEID K, HUNTER ZR & TREON SP 2015b. Overall survival and competing risks of death in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. British Journal of Haematology, 169, 81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILLO JJ, OLSZEWSKI AJ, KANAN S, MEID K, HUNTER ZR & TREON SP 2015c. Survival outcomes of secondary cancers in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: An analysis of the SEER database. American Journal of Hematology, 90, 696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG MP, KUSZTOS AE, GUSTINE JN, DRYDEN-PETERSON SL, DUBEAU TE, WOOLLEY AE, HAMMOND SP, BADEN LR, TREON SP, CASTILLO JJ & ISSA NC 2019. Low risk of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and invasive aspergillosis in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinaemia on ibrutinib. British Journal of Haematology, 185, 788–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DECKERT A 2016. The existence of standard-biased mortality ratios due to death certificate misclassification - a simulation study based on a true story. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology, 16, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIMOPOULOS MA, PANAYIOTIDIS P, MOULOPOULOS LA, SFIKAKIS P & DALAKAS M 2000. Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia: Clinical Features, Complications, and Management. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 18, 214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF THE LIVER 2017. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology, 67, 370–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILLATRE P, DECAUX O, JOUNEAU S, REVEST M, GACOUIN A, ROBERT-GANGNEUX F, FRESNEL A, GUIGUEN C, LE TULZO Y, JEGO P & TATTEVIN P 2014. Incidence of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia among groups at risk in HIV-negative patients. The American Journal of Medicine, 127, 1242.e11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRITZ A, PERCY C, JACK A, SHANMURGARATHAN S, SOBIN L, PARKIN DM & WHELAN S 2013. International classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O) – 3rd edition, 1st revision, Geneva, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- FUNG M, JACOBSEN E, FREEDMAN A, PRESTES D, FARMAKIOTIS D, GU X, NGUYEN PL & KOO S 2019. Increased Risk of Infectious Complications in Older Patients With Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Exposed to Bendamustine. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68, 247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANGULI M & RODRIGUEZ EG 1999. Reporting of Dementia on Death Certificates: A Community Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47, 842–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCÍA-SANZ R, MONTOTO S, TORREQUEBRADA A, GARCÍA DE COCA A, PETIT J, SUREDA A, RODRÍGUEZ-GARCIA JA, MASSÓ P, PÉREZ-ALIAGA A, DOLORES M, BESALDUCH J, JARQUE I, SALAMA P, RIVAS JAH, NAVARRO B, BLADÉ J & SAN MIGUEL JF 2001. Waldenström macroglobulinaemia: presenting features and outcome in a series with 217 cases. British Journal of Hematology, 115, 575–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERTZ MA 2015. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. American Journal of Hematology, 90, 346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON TM, MORTON LM, SHIELS MS, CLARKE CA & ENGELS EA 2014. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes in HIV-infected people during the HAART era: a population-based study. AIDS, 28, 2313–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIORDANO TP, HENDERSON L, LANDGREN O, CHIAO EY, KRAMER JR, EL-SERAG H & ENGELS EA 2009. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphoproliferative precursor diseases in US veterans with hepatitis C virus. JAMA, 297, 2010–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOOLEY TA, LEISENRING W, CROWLEY J & STORER BE 1999. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS NL, JAFFE ES, STEIN H, BANKS PM, CHAN JK, CLEARY ML, DELSOL G, DE WOLF-PEETERS C, FALINI B & GATTER KC 1994. A Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: A Proposal From the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood, 84, 1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERNÁNDEZ-DÍAZ S & GARCÍA RODRÍGUEZ LA 2001. Steroids and Risk of Upper Gastrointestinal Complications. American Journal of Epidemiology, 153, 1089–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWLADER N, NOONE AM, KRAPCHO M, MILLER D, BREST A, YU M, RUHL J, TATALOVICH Z, MARIOTTO A, LEWIS DR, CHEN HS, E.J. F & CRONIN KA 2019. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- IVES DG, SAMUEL P, PSATY BM & KULLER LH 2009. Agreement between nosologist and cardiovascular health study review of deaths: implications of coding differences. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAFFE ES, HARRIS NL, STEIN H & VARDIMAN JW 2001. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, Lyon, IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- KARLSSON J, ANDREASSON B, KONDORI N, ERMAN E, RIESBECK K, HOGEVIK H & WENNERAS C 2011. Comparative study of immune status to infectious agents in elderly patients with multiple myeloma, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology, 18, 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASTRITIS E, KYRTSONIS MC, MOREL P, GAVRIATOPOULOU M, HATJIHARISSI E, SYMEONIDIS AS, VASSOU A, REPOUSIS P, DELIMPASI S, SIONI A, MICHALIS E, MICHAEL M, VERVESSOU E, VOULGARELIS M, TSATALAS C, TERPOS E & DIMOPOULOS MA 2015. Competing risk survival analysis in patients with symptomatic Waldenström macroglobulinemia: the impact of disease unrelated mortality and of rituximab-based primary therapy. Haematologica, 100, e446–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASTRITIS E, LEBLOND V, DIMOPOULOS MA, KIMBY E, STABER P, KERSTEN MJ, TEDESCHI A, BUSKE C & COMMITTEE EG 2018. Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 29, iv41–iv50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSHIOL J, GRIDLEY G, ENGELS EA, MCMASTER ML & LANDGREN O 2008. Chronic immune stimulation and subsequent Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1903–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISTINSSON SY, KOSHIOL J, BJORKHOLM M, GOLDIN LR, MCMASTER ML, TURESSON I & LANDGREN O 2010. Immune-related and inflammatory conditions and risk of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma or Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 102, 557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEBLOND V, JOHNSON S, CHEVRET S, COPPLESTONE A, RULE S, TOURNILHAC O, SEYMOUR JF, PATMORE RD, WRIGHT D, MOREL P, DILHUYDY MS, WILLOUGHBY S, DARTIGEAS C, MALPHETTES M, ROYER B, EWINGS M, PRATT G, LEJEUNE J, NGUYEN-KHAC F, CHOQUET S & OWEN RG 2013. Results of a randomized trial of chlorambucil versus fludarabine for patients with untreated Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, or lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEBLOND V, KASTRITIS E, ADVANI R, ANSELL SM, BUSKE C, CASTILLO JJ, GARCIA-SANZ R, GERTZ M, KIMBY E, KYRIAKOU C, MERLINI G, MINNEMA MC, MOREL P, MORRA E, RUMMEL M, WECHALEKAR A, PATTERSON CJ, TREON SP & DIMOPOULOS MA 2016. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Blood, 128, 1321–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LELEU X, SOUMERAI J, ROCCARO A, HATJIHARISSI E, HUNTER ZR, MANNING R, CICCARELLI BT, SACCO A, IOAKIMIDIS L, ADAMIA S, MOREAU AS, PATTERSON CJ, GHOBRIAL IM & TREON SP 2009. Increased incidence of transformation and myelodysplasia/acute leukemia in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia treated with nucleoside analogs. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACERA CA, SUN RKP, YEAGER KK & BRANDES DA 1992. Sensitivity and Specificity of Death Certificate Diagnoses for Dementing Illnesses, 1988–1990. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCSHANE CM, MURRAY LJ, ENGELS EA & ANDERSON LA 2014. Community-acquired infections associated with increased risk of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia. British Journal of Haematology, 164, 653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEHTA J & SINGHAL S 2003. Hyperviscosity Syndrome in Plasma Cell Dyscrasias. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 29, 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIENO MN, TANAKA N, ARAI T, KAWAHARA T, KUCHIBA A, ISHIKAWA S & SAWABE M 2016. Accuracy of Death Certificates and Assessment of Factors for Misclassification of Underlying Cause of Death. Journal of Epidemiology, 26, 191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRA E, VARETTONI M, TEDESCHI A, ARCAINI L, RICCI F, PASCUTTO C, RATTOTTI S, VISMARA E, PARIS L & CAZZOLA M 2013. Associated cancers in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: clues for common genetic predisposition. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma, and Leukemia, 13, 700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARUM S, WESTERGREN T & KLEMP M 2014. Corticosteroids and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 4, e004587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIPP R, MITCHELL A, PISHKO A & METJIAN A 2014. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia in hepatitis C: case report and review of the current literature. Case Reports in Oncological Medicine, 2014, 165670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OJHA RP & THERTULIEN R 2012. Second malignancies among Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia patients: small samples and sparse data. Annals of Oncology, 23, 542–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSZEWSKI AJ, CHEN C, GUTMAN R, TREON SP & CASTILLO JJ 2017. Comparative outcomes of immunochemotherapy regimens in Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia. British Journal of Haematology, 179, 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSZEWSKI AJ, REAGAN JL & CASTILLO JJ 2018. Late infections and secondary malignancies after bendamustine/rituximab or RCHOP/RCVP chemotherapy for B-cell lymphomas. American Journal of Hematology, 93, E1–E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWEN RG, T. S, AL-KATIB A, FONSECA R, GREIPP PR, MCMASTER ML, MORRA E, PANGALIS GA, SAN MIGUEL JF, BRANAGAN AR, DIMOPOULOS MA 2003. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Seminars in Oncology, 30, 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRESTON D, LUBIN J, PIERCE D, MCCONNEY M & SHILNIKOVA N 2015. Epicure risk regression and person-year computation software: command summary and user guide. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Risk Sciences International. [Google Scholar]

- RAO KV & FASO A 2012. Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: Optimizing Prevention and Management. American Health and Drug Benefits, 5, 232–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REVOLINSKI SL & MUNOZ-PRICE LS 2018. Clostridium difficile in Immunocompromised Hosts: A Review of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Treatment, and Prevention. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2144–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMERO JP, BENITO-LEÓN J, MITCHELL AJ, TRINCADO R & BERMEJO-PAREJA F 2014. Under reporting of dementia deaths on death certificates using data from a population-based study (NEDICES). Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 39, 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STURGEON KM, DENG L, BLUETHMANN SM, ZHOU S, TRIFILETTI DM, JIANG C, KELLY SP & ZAORSKY NG 2019. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. European Heart Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SURVEILLANCE RESEARCH PROGRAM National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software. In: PROGRAM SR (ed.) 8.3.5 ed.: Surveillance Research Program. [Google Scholar]

- SWERDLOW SH, CAMPO E & HARRIS NLEA 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- TREON SP, DIMOPOULOS M & KYLE RA 2003. Defining Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Seminars in Oncology, 30, 107–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAJDIC CM, LANDGREN O, MCMASTER ML, SLAGER SL, BROOKS-WILSON A, SMITH A, STAINES A, DOGAN A, ANSELL SM, SAMPSON JN, MORTON LM & LINET MS 2014. Medical history, lifestyle, family history, and occupational risk factors for lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: the InterLymph Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes Project. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs, 2014, 87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARETTONI M, TEDESCHI A, ARCAINI L, PASCUTTO C, VISMARA E, ORLANDI E, RICCI F, CORSO A, GRECO A, MANGIACAVALLI S, LAZZARINO M & MORRA E 2012. Risk of second cancers in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Annals of Oncology, 23, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARUGHESE T, TAUR Y, COHEN N, PALOMBA ML, SEO SK, HOHL TM & REDELMAN-SIDI G 2018. Serious Infections in Patients Receiving Ibrutinib for Treatment of Lymphoid Cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 67, 687–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 2017. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. In: SWERDLOW SH, E. C, HARRIS NL, JAFFE ES, PILERI SA, STEIN H, THIELE J (ed.) 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- YEO W, CHAN PK, ZHONG S, HO WM, STEINBERG JL, TAM JS, HUI P, LEUNG NW, ZEE B & JOHNSON PJ 2000. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. Journal of Medical Virology, 62, 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.