Abstract

Background

Risk models in the private insurance setting may systematically underpredict in the socially disadvantaged. In this study, we sought to determine if US minority Medicare beneficiaries had disproportionately low costs compared to their clinical outcomes and if adding social determinants of health (SDOH) into risk prediction models improves prediction accuracy.

Methods and Results

Retrospective observational cohort study of 2016–2017 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) data (N=3,614) linked to Medicare fee-for-service claims. Logistic and linear regressions were used to determine the relationship between race/ethnicity and annual costs of care, all-cause hospitalization, CV hospitalization, and death. We calculated observed to expected (O:E) ratios for all outcomes under four risk models: 1) age + gender 2) Model 1 + clinical comorbidity adjustment, 3) Model 2 + SDOH, and 4) SDOH alone. Our sample was 44% male and 11% Black or Hispanic. Among minorities, adverse clinical outcomes were inversely related to cost. After multivariable adjustment, Blacks/Hispanics had higher rates of CV hospitalization (IRR 1.78, p=0.012), but similar annual costs ($−336, p=0.77) compared to whites. Among whites, models 1–4 all showed similar O:E ratios, suggesting high accuracy in risk prediction using current models. Among minorities, adjustment for age, gender, and comorbidities under-predicted all-cause hospitalization by 20% (O:E=1.20), CV hospitalization by 70% (O:E=1.70); and overpredicted death by 21% (O:E=0.79); adding SDOH brought O:E near 1 for all outcomes. Among both groups, the SDOH risk model alone performed with equal or superior accuracy to the model based on clinical comorbidities.

Conclusions

A paradoxical relationship was observed between clinical outcomes and costs among racial/ethnic minorities. Because of systematic differences in access to care, cost may not be an appropriate surrogate for predicting clinical risk among vulnerable populations. Adjustment for SDOH improves the accuracy of risk models among racial/ethnic minorities, and could guide use of prevention strategies.

Hospitals and clinicians are increasingly held accountable for patients’ outcomes and costs of care, as Medicare and other payers move from paying for volume to paying for value. As a result, health systems often rely on algorithms and risk-prediction models to identify high-risk patients that may benefit from interventions. Many of these models are built with costs as their primary outcome, with the idea that high-cost patients are the group that warrants the most targeted and aggressive intervention to improve outcomes.

One prior study demonstrated that uneven access to healthcare among racial and ethnic minorities may lead cost prediction models to systematically underpredict costs for high-risk groups, which could lead these groups to receive interventions to improve health outcomes at inappropriately low rates.1 Similarly, studies on two current gold standard clinical risk prediction tools used in cardiovascular medicine, the pooled cohorts equation (PCE) and the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) demonstrate that these models underestimate risk for racial and ethnic minority groups and overestimate risk for whites.2–4 If costs and clinical risk are systematically mispredicted by current models, the application of such tools to clinical practice could further widen racial and ethnic disparities by failing to match needs to interventions for at-risk groups.

Numerous studies have documented the importance of social determinants of health (SDOH), such as food insecurity, housing instability, and education level, as important drivers of health outcomes.5–9 This is highly relevant for minorities, who have higher prevalence rates of these social risk factors.10 This is due in part to the negative effects of structural racism and segregation, which have led to disproportionately higher proportions of racial and ethnic minorities living in areas of poor social and economic conditions.11 However, few studies have examined whether the addition of SDOH into risk prediction models improves risk prediction accuracy and whether these improvements differ by race. Prior studies have incorporated few indicators of social risk, or were conducted in small, single center populations.2, 12 Understanding how adding SDOH to these models impacts risk prediction for racial and ethnic minorities could allow health systems and clinicians to more accurately identify high-risk groups for targeted interventions and avoid exacerbating disparities in care.

Therefore, in this study, we sought to examine if the addition of SDOH into risk prediction models improves prediction accuracy for minorities. We used a nationally representative sample of US Medicare beneficiaries to determine 1) whether racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries had disproportionately low predicted costs compared to their clinical outcomes; 2) if current risk models differ in their accuracy in predicting risk for cardiovascular hospitalization, death, and annual cost between racial and ethnic minorities and whites; and 3) whether the addition of a robust panel of social determinant factors could improve risk prediction accuracy.

Methods

Data source and study sample

Due to the sensitive nature of the data for this study, the authors are not authorized to share the data. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provides a Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) public use file free for download on their webpage. Requests to access the full MCBS dataset must be requested through the Limited Data Set File Process at cms.gov.

This was a retrospective observational study of 2016–2017 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) data linked to fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare claims. The MCBS is a continuous, in-person survey with a 4 year longitudinal design. It is conducted annually and is a nationally representative sample of Medicare participants. Study inclusion was limited to 4,703 participants who had 12 consecutive months of enrollment in the MCBS and in FFS Medicare in the baseline year (2016), and 12 months of enrollment or death in the following year (2017). Participants institutionalized in long-term care or without a United States (US) Zip Code in the baseline year were excluded (n=561). We further excluded 528 participants for missing data on at least one key study variable of interest (Problem sleeping n=527, Angina n=133, overweight n=133, ADL n=133, IADL n=133), leaving a final study sample of 3,614 individuals (Supplemental Figure 1).

Definition of groups

Race was self-reported during survey interview and participants were classified as White (n=3,138), Black (n=281), Hispanic (n=61), Asian (n=31), Native American or Pacific Islander (n=26), and unspecified (n=67). We classified their responses into two categories: White/Other and Black/Hispanic (minority). Participants were designated as poor if they were dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. We also identified participants’ age, gender, and certain comorbidities including hypertension, dyslipidemia, disordered sleep, overweight, obesity, diabetes, coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/asthma, and heart failure. All of the above conditions were identified in the medical claims of participants with ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes according to the algorithms defined by the Medicare Chronic Condition Warehouse13, except for disordered sleep, overweight and obesity, which were identified using survey questions in the MCBS.

Selection of social determinant variables

Social determinant variables were selected in a two-step process. Firstly, variables were selected based on variables included in the CMS social determinants assessment.14 Variables identified as particularly impactful for cardiovascular outcomes by the American Heart Association were also selected.5 Secondly, these variables were then assessed according to three key factors: feasibility of collection, potential to be actionable, and potential for impact. The final list included the following variables, spanning seven core SDOH domains: 1: Neighborhood and the built environment (rural versus urban residence), 2: Behaviors and Habits (Alcohol abuse), 3: Access to care (answers to questions on whether the respondent has trouble getting care, how well patient speaks English, belief that doctor is concerned with patient’s overall health, whether patient has confidence in doctor, whether patient finds it easy to get to doctor from their home, whether patient reports there is adequate access to specialists), 4: Economic status (income, income to poverty level), 5. Financial strain (answers to questions on whether the respondent has medical bills in collection, ever delayed medical care due to costs, or ever did not seek medical care at all due to costs) 6: Social support (Marital status), and 7: Education: (Level of schooling completed). For more detailed information about these variables, please see Supplemental Table 1.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes for the study were all-cause hospitalization, CV hospitalization, death, and annual cost. All primary outcomes were ascertained during the follow up year, 2017. All cause hospitalization was defined as all inpatient hospitalizations listed in participants’ Part A claims. CV hospitalization was defined as an inpatient stay (as defined above) with a primary cardiovascular discharge diagnosis ICD-10-CM code. Annual costs were defined as the total amount reimbursed by Medicare for all Part A and Part B services. Death was measured using the date of death recorded by the MCBS using Medicare administrative records.

Analysis

First, we computed descriptive statistics for the SDOH predictor variables as well as age, gender, and comorbid conditions (as means or proportions). We also computed descriptive statistics as incidence rates per 100 population on hospitalization outcomes, means on cost outcomes, and proportions on mortality outcomes.

Next, we assessed the unadjusted association between race and the outcome variables, using univariate negative binomial regression (hospitalization outcomes), logistic regression (mortality outcome), and ordinary least squares regression (cost outcome). We reported these results as incidence rate ratios, odds ratios, and cost coefficients.

Finally, we estimated four sets of multivariable regression models for each of our four outcomes in order to predict these outcomes under each of the modeling scenarios. We modeled each outcome according to the regression methods appropriate to each outcome as specified above. For Model 1, we used age and gender to predict each of our four outcomes at the participant level. For Model 2, we added the CMS hierarchical condition categories (CMS-HCC) risk adjustment model to Model 1. The CMS hierarchical condition categories (CMS-HCC) risk adjustment model assigns “points” for age, gender, original reason for Medicare eligibility, dual Medicaid enrollment (in some cases), institutionalization in long-term care, and 83 clinical conditions identified by diagnoses in Medicare claims.15 CMS-HCC ranks diagnoses into categories representative of conditions with similar cost patterns; higher categories correlate with higher predicted costs and result in higher risk scores. For Model 3, we added SDOH risk factors to Model 2. For Model 4, we only used SDOH risk factors to predict outcomes. Each model was run independently of all of the other models in the analysis. For the cost model, we examined the residuals from the CMS-HCC and CMS-HCC plus SDOH models to examine model fit (Supplemental Figure 2).

We compared the predicted (i.e. expected) to the actual (i.e. observed) outcomes, taking the average of these across the entire population, and then using observed to expected (O:E) event ratios to compare the accuracy of each modelling scenario in our study population. An O:E ratio greater than 1 implies the model under-predicted the actual event, and less than 1 implies the model over-predicted the actual event. In this way, the O:E ratios tell us which modelling scenario provides the most accurate predictions. We further stratified our O:E ratios by the White/Other versus Black/Hispanic population in order to determine which modelling scenario generated the most accurate predictions in these at-risk sub-populations.

Statistical package used

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 and Stata 14.2. Statistical significance was defined as P-value <0.05. This study was considered to be non-human subjects research due to the de-identified nature of the data. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St Louis. All analysis was performed in compliance with the MCBS data use agreement.

Results

Study population

3,614 MCBS participants were included in our study. (Table 1). Our sample was 44% male, 11% Black/Hispanic, and 16% poor. The majority of the patients (71%) were between the ages of 65 and 84. The prevalence of comorbid conditions was high, with hypertension (61%) and dyslipidemia (54%) being the most prevalent. Other cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes and obesity were present in about a third of the beneficiaries (27% and 31%, respectively). Coronary artery disease was prevalent in 25% of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Overall | White/Other | Black/Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N Patient Years with no missing variables | 3,614 | 3,272 | 342 |

| Demographics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 56.0% | 56.0% | 56.4% |

| Male | 44.0% | 44.0% | 43.6% |

| Age | |||

| Mean age (years) | 73 | 73 | 65 |

| <65 | 15.3% | 12.9% | 38.3% |

| 65–75 | 35.4% | 36.3% | 26.6% |

| 75–84 | 35.3% | 36.5% | 24.6% |

| ≥85 | 14.0% | 14.3% | 10.5% |

| Original Reason for Medicare Eligibility | |||

| ESRD | 1.1% | 0.8% | 3.5% |

| Disability | 14.1% | 12.0% | 34.8% |

| Age ≥ 65 | 84.8% | 87.2% | 61.7% |

| Dual Enrollee in Medicaid and Medicare | 16.2% | 13.2% | 44.7% |

| HCC Risk Score (Mean) | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.26 |

| Clinical and Cardiovascular Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 61.1% | 60.5% | 66.4% |

| Dyslipidemia | 53.6% | 54.3% | 46.8% |

| Coronary artery disease | 24.8% | 25.0% | 22.8% |

| Angina | 9.2% | 9.4% | 7.3% |

| Stroke (CVA,TIA) | 3.8% | 3.6% | 5.6% |

| Heart Failure | 10.7% | 10.2% | 15.8% |

| Arrhythmia | 10.8% | 11.3% | 5.6% |

| Obesity (BMI>30) | 30.5% | 29.1% | 43.6% |

| Diabetes | 26.5% | 25.4% | 37.4% |

| Renal Insufficiency | 19.2% | 18.3% | 28.1% |

| COPD/Asthma | 15.1% | 15.2% | 14.0% |

| Disordered sleep | 35.3% | 35.0% | 37.4% |

| Dementia | 4.1% | 4.2% | 3.5% |

| Tobacco | 9.9% | 9.5% | 13.5% |

| Depression | 14.0% | 14.3% | 11.4% |

BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV: Cardiovascular disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; ESRD: End-stage renal disease; HCC: Hierarchical Condition Category; TIA: transient ischemic stroke

Compared to White/Other beneficiaries, Black and Hispanic beneficiaries were more likely to be dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare (45% vs 13%) and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, such as hypertension (66% vs 61%), heart failure (16% vs 10%), obesity (44% vs 29%), diabetes (37% vs 25%), renal insufficiency (28% vs 18%), and tobacco use (14% vs 10%).

Prevalence of social risk factors

The burden of social risk was high among beneficiaries (Table 2). Nearly half of participants had low social support (defined as not being married). Financial strain was reported in 11% of participants, 16% were living at <100% below poverty, and 17% had limited access to care. Most beneficiaries had completed high school or some college (57%), while some (15%) had no high school education or lower. Many beneficiaries (41%) were low income, reporting <$25,000/year in income.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Social Determinant Risk Factors

| Overall | White/Other | Black/Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Income | |||

| ≤25,000 | 41.2% | 38.0% | 71.9% |

| >25,000 and <50,000 | 24.8% | 25.9% | 14.6% |

| ≥ 50,000 | 34.0% | 36.2% | 13.5% |

| Education | |||

| No high school or college education | 14.7% | 12.7% | 33.6% |

| High school/Some college | 59.4% | 59.7% | 56.4% |

| College/graduate school education | 25.9% | 27.6% | 9.9% |

| Race | |||

| White | 87.1% | 96.2% | 0.0% |

| Black/Hispanic | 9.5% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Other/Unknown | 3.4% | 3.8% | 0.0% |

| Financial Strain | |||

| Yes | 11.0% | 9.4% | 26.6% |

| No | 89.0% | 90.6% | 73.4% |

| Income to Poverty Ratio | |||

| ≤100% | 15.9% | 13.3% | 41.2% |

| >100% and ≤200% | 24.4% | 23.7% | 31.0% |

| >200% | 59.7% | 63.0% | 27.8% |

| Alcohol problem | |||

| Yes | 13.8% | 13.2% | 19.0% |

| No | 86.2% | 86.8% | 81.0% |

| Social Support | |||

| Not Married | 51.6% | 49.8% | 69.0% |

| Residential environment | |||

| Urban-Rural Location | |||

| Metropolitan | 67.8% | 66.8% | 77.8% |

| Micropolitan | 17.2% | 17.5% | 14.0% |

| Rural | 15.0% | 15.7% | 8.2% |

| Access to care | |||

| Yes | 83.4% | 84.8% | 69.9% |

| No | 16.6% | 15.2% | 30.1% |

Compared to White/other beneficiaries, Black/Hispanic beneficiaries were more likely to have income <$25,000 (72% vs 38%), no high school or college education (34% vs 13%), be living at <100% below poverty (41% vs 13%), and report financial strain (27% vs 9%), lack of social support (69% vs 50%), and limited access to care (30% vs 15%).

Relationship between clinical outcomes and costs of care

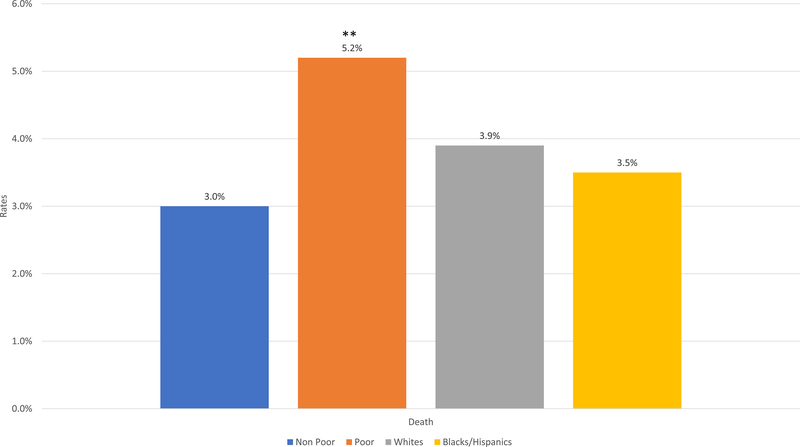

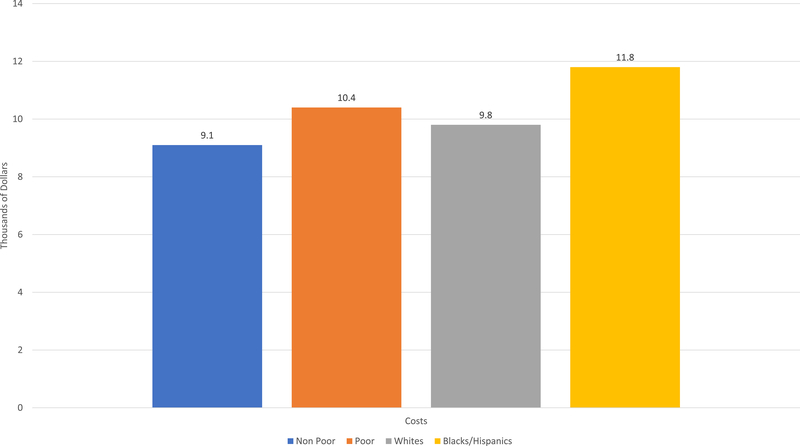

Prior to risk adjustment, compared to White/others, Black/Hispanic beneficiaries had higher rates of all-cause hospitalization (48 vs 29 per 100, p=0.004) and CV hospitalization (16 vs. 7.7 per 100, p=0.011), similar rates of death (3.4% vs 3.9%, p=0.451), and no significant difference in annual costs of care ($11,754 vs. $9,849, p=0.080) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) All-cause hospitalization and cardiovascular hospitalization; (B) Death; (C) Costs. *p<0.05; **p<0.001; CV: Cardiovascular disease

In fully adjusted models, higher age and clinical comorbidity burden correlated with higher risk for adverse events, and there was directional agreement in groups defined by these features between adverse events and annual cost (Table 3). For example, those in the highest tertile of comorbidity index had the highest rates of adverse outcomes as well as higher costs compared to those in mid and low tertiles of clinical risk (all-cause hospitalization Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) = 3.29; cardiovascular hospitalization IRR = 4.37, death odds ratio (OR) = 3.35; cost differential: $8641, p<0.001 for all).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Fully Adjusted Differential in Annual Costs of Care; Fully Adjusted Rates for All Cause Hospitalization, CV Hospitalization, and Odds of Death by Social Risk Factor

| Unadjusted | Fully Adjusted Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Annual Costs ($) | Difference in cost ($) | All Cause Hospitalization (IRR) | CV Hospitalization (IRR) | Death (OR) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||||

| Low Tertile | 5,752 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Middle Tertile | 8,505 | 2,518* | 1.63† | 2.45† | 1.53 |

| High Tertile | 16,460 | 8,641† | 3.29† | 4.37† | 3.35† |

| Age | |||||

| <65 | 9,167 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 65–75 | 8,677 | 9,970* | 1.57 | 2.98 | 4.05 |

| 75–85 | 10,033 | 9,911* | 1.83 | 3.99 | 8.41 |

| ≥85 | 13,659 | 12,966† | 2.80* | 6.39* | 26.87* |

| Annual Income | |||||

| ≤25,000 | 11,132 | −373 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.83 |

| >25,000 and <50,000 | 9,348 | −330 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.28 |

| ≥50,000 | 8,891 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Education | |||||

| No high school or college education | 11,775 | 219 | 1.17 | 1.62 | 0.83 |

| High school/some college | 9,634 | −712 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 0.66 |

| College/graduate school education | 9,549 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race | |||||

| White | 9,849 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black/Hispanic | 11,754 | −336 | 1.24 | 1.78* | 0.77 |

| Other | 6,876 | −2,712 | 0.86 | 0.42 | 0.66 |

| Financial Strain | |||||

| Yes | 11,055 | 167 | 1.18 | 1.36 | 0.92 |

| No | 9,787 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Income to Poverty Ratio | |||||

| ≤100% | 10,380 | −638 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 2.05 |

| >100% and ≤200% | 11,754 | 1,900 | 1.17 | 1.37 | 1.86 |

| >200% | 9,060 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Behavioral Factors | |||||

| Alcohol Problem | |||||

| Yes | 12,501 | 2,720* | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.41 |

| No | 9,516 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Social Support | |||||

| Not Married | 10,844 | 1,285 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.10 |

| Residential Environment | |||||

| Rurality | |||||

| Metropolitan | 10,622 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Micropolitan | 7,983 | −2,420* | 0.82 | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| Rural | 9,007 | −1,121 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 1.48 |

| Access to Care | |||||

| Yes | 9,594 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No | 11,606 | 2,001* | 1.17 | 1.09 | 1.01 |

p<0.05

p<0.001

CV: cardiovascular disease; IRR: incidence rate ratio; OR: odds ratio

However, among racial and ethnic minorities, adverse clinical outcomes were inversely related to cost. After multivariable adjustment, Blacks/Hispanics had higher rates of CV hospitalization (IRR 1.78, p=0.012), but similar annual costs (difference in cost $−336, p=0.77) compared to Whites/others. This pattern of similar annual costs, despite higher rates of adverse clinical outcomes, was also observed for those whose income was <25,000/year, those who had less than a college education, and those reporting living at an income to poverty ratio of <100% (difference in costs $−373, $−712, & $−638, respectively, p>0.05).

Accuracy of risk adjustment models

In Whites/others, after age and gender adjustment alone, all-cause hospitalization (O:E 0.94), death (O:E 1.00) and costs (O:E 0.98) all saw good agreement between observed and expected outcomes, while CV Hospitalizations were overpredicted by 11% (O:E 0.89, Table 4). Adding the CMS-HCC model elements showed similar O:E across all outcomes as the age and gender adjusted model. The addition of SDOH to the models brought O:E ratios closer to 1 for CV hospitalization and maintained good agreement across the remaining outcomes. Overall, among whites, the difference in O:E ratios across all four models was minimal.

Table 4.

Summary Observed to Expected Ratios in Sequentially Adjusted Models

| White/Other | Black/Hispanic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Model 1 Age and Gender |

Model 2 CMS-HCC Model |

Model 3 CMS-HCC +SDOH risk model |

Model 4 SDOH risk model alone |

Unadjusted | Model 1 Age and Gender |

Model 2 CMS-HCC Model |

Model 3 CMS-HCC +SDOH risk model |

Model 4 SDOH risk model alone |

|

| Annual Incidence* of All Cause Hospitalization | 29.2 | 31.0 | 30.7 | 29.8 | 29.2 | 48.0 | 31.1 | 39.9 | 47.4 | 49.0 |

| Annual Incidence* of Hospitalizations for CVD | 7.5 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 16.1 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 15.6 | 16.5 |

| Death | 3.9% | 3.9% | 3.8% | 3.9% | 3.9% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 4.4% | 3.5% | 3.5% |

| Total Annual Cost | 9,736 | 9,951 | 9,718 | 9,736 | 9,736 | 11,754 | 9,699 | 11,928 | 11,754 | 11,754 |

| Observed to Expected Ratios | Observed to Expected Ratios | |||||||||

| Any Cause Hospitalization | -- | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.00 | -- | 1.54 | 1.20 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| Hospitalizations for CVD | -- | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.99 | -- | 2.18 | 1.70 | 1.03 | 0.96 |

| Death | -- | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | 1.02 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total Annual Cost | -- | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Annual incidence per 100 population

An O:E ratio greater than 1 implies that the model under-predicted actual event rates or costs in the population of interest.

An O:E ratio less than 1 implies that the model over-predicted actual event rates of costs in the population of interest.

CMS: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HCC: Hierarchical Condition Category; SDOH: social determinants of Health

In contrast, among blacks and Hispanics, adjusting for age and gender underpredicted all-cause hospitalization (O:E 1.54), CV hospitalization (O:E 2.18), death (O:E 1.02), and costs (O:E 1.21). Including CMS-HCC to adjust for clinical comorbidities reduced O:E ratios near one for total costs, but still significantly underpredicted all-cause and CV hospitalizations, which were underpredicted by 20% (O:E 1.20) and 70% (O:E 1.70), respectively. After the inclusion of SDOH in the models, the O:E ratio for all events was brought near to one.

Predictions by social risk alone

Among both groups, the social risk model alone performed as well as the models including demographic, cost, and clinical comorbidity adjustment. For Whites/Others, the SDOH risk model alone performed most accurately among all models tested with O:E=1 for all outcomes except for CV hospitalization where O:E=0.99. Similarly for Blacks/Hispanics, the SDOH risk model showed nearly perfect agreement in observed to expected events across all outcomes (O:E=0.98 and 0.96 for all-cause and CV hospitalization respectively), and O:E=1 for death and annual costs. This model showed more accuracy than age and gender adjustment or the CMS-HCC adjustment models, and similar agreement to the CMS-HCC+SDOH risk-adjustment models.

Discussion

In this study, we found a paradoxical relationship between adverse outcomes and cost among racial/ethnic minorities. For White/Other beneficiaries, risk for all events was predicted with high accuracy in traditional clinical comorbidity based models. Among minorities, who were considerably more socioeconomically disadvantaged, risk was significantly underpredicted in these models. However, adjusting for social risk improved the predictive accuracy of models for racial/ethnic minorities. Among both groups, SDOH risk alone provided accurate prediction of risk for all outcomes studied.

Our first finding was to confirm the paradoxical relationship between clinical outcomes and costs among racial and ethnic minorities, using a nationally-representative population of older adults. This is important to consider when using cost based prediction models and suggests that cost may be an inadequate to identify high risk patients in need of interventions. As we shift from fee-for-service to value-based payment models, health care systems and hospitals are becoming increasingly interested in ways to mitigate the impact of social risk on the bottom line;16 if models fail to account for the potential distortion in cost models related to unequal access to care, interventions based on high-cost status may be inappropriately targeted for optimal effect, and may systematically under-enroll racial and ethnic minorities.

Our second finding was that current risk prediction models perform better for whites than for racial and ethnic minorities across a range of cost and clinical outcomes. Further, these data suggest that the addition of SDOH to risk models may provide an opportunity to improve the performance of these models for everyone. Our findings are consistent with previous literature on clinical comorbidity focused risk prediction tools (such as the PCE and FRS), which have been shown to overestimate risk in the affluent and underestimate risk in the socially high-risk.2, 3 One prior study demonstrated improvement in primary risk prediction models for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) after including neighborhood level social risk.12 However, to our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the influence of SDOH on risk prediction outside of primary risk prediction.

Our study supports the importance of social risk for accurate risk assessment, particularly among minorities. Race-based differences in the importance of social risk for accurate risk prediction may be in part due to unmeasured differences between black and white patients that are related to the differential lived experiences of blacks versus whites in the US. For example,17 structural racism, and the impact of discrimination and racism unique to minorities,18 are associated with both a higher burden of social risk factors and also independently associated with stress,19, 20 inflammation, and negative health outcomes.21 This supports arguments to push for integration of SDOH into risk prediction and clinical assessment where feasible, because it would allow us to better and more equitably identify at-risk patients and intervene on that risk accordingly.22

Perhaps the most striking finding in this analysis was that the SDOH risk model alone performed with near 100% precision among both minorities and non-minority patients independent of adjustment for clinical comorbidities or costs. This underscores the importance of these factors as important determinants of outcomes, as well as the need to continue to develop effective strategies to collect and utilize these data if our aim is accuracy in risk prediction. Currently, there is ongoing debate as to whether it is feasible or useful to include social risk in clinical management.23, 24 Physicians have been reluctant to screen for these factors,25 due to the sheer volume of social risk factors, lack of standardization of methods to collect them, and unclear direction as to how to address them.23 It will be important to conduct systematic study and identification of key barriers and enablers to the collection and use of these data across use cases and contexts. However, health systems and insurers have begun to think about and pilot interventions to directly impact social determinants of health, by providing housing, transportation, and other key services. Whether these interventions are best positioned in the health care delivery system or whether they should be addressed by broader strategies to improve economic opportunity remains to be seen, but represents important areas for future work for both researchers and policymakers.

Limitations

There are several limitations. First, predictor variables were collected via survey, which makes the data vulnerable to certain biases (recall bias, response bias, question order bias). Secondly, socially disadvantaged patients may have lower health literacy, which may limit the accuracy of reporting of comorbid conditions or other variables for these groups. Thirdly, although we chose variables based on previous studies on SDOH, this specific panel of social determinants has not been previously validated. Finally, our cost model was poorly predictive for the small number of individuals with extremely high costs, which is a problem with cost modeling using OLS more broadly; we elected that method because we aimed to evaluate the relationship between race, social risk factors, and costs under the models that CMS currently uses to measure costs in a number of national quality and pay-for-performance programs. Improving upon the methods of the model itself is beyond the scope of this paper but may be an important area for future work.

Conclusions

A paradoxical relationship was observed between adverse outcomes and cost among racial/ethnic minorities, and those from low socioeconomic groups. Because of systematic differences in access to care, cost may not be an appropriate surrogate for predicting clinical risk among the poor or other vulnerable populations, and algorithms that are based on cost alone may lead to inadequate risk prediction. We found that including social risk in models predicting costs and clinical outcomes improves model accuracy among racial and ethnic minorities. Outcome studies will be required to assess the efficacy of modifying treatment based on reclassification of risk using social determinants data. Further exploration of these models may improve risk prediction for overall and CV events among vulnerable populations and guide more optimal use of prevention strategies.

Supplementary Material

What is Known.

Interventions that are directed at high-cost patients may under-target racial and ethnic minorities, who were shown in one prior study to have relatively lower costs but worse clinical outcomes.

Social determinants of health are major drivers of poor health outcomes, and racial and ethnic minorities have a higher burden of these social determinants.

What the Study Adds.

Adding social determinants data to current risk prediction models improved model accuracy for hospitalization, death, and costs of care among Racial and Ethnic minorities in a large, nationally representative cohort of older US Adults.

A model based on social determinants of health alone predicted health outcomes and costs as well as one based on clinical comorbidities.

Including social determinants in prediction models could improve equity in preventive care by more accurately targeting interventions to people at the highest clinical risk.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Gmerice Hammond, MD MPH is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32HL007081.

Disclosures: Dr. Joynt Maddox receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL143421) (significant) and National Institute on Aging (R01AG060935) (significant), and previously did contract work for the US Department of Health and Human Services (significant).

References

- 1.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C and Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366:447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colantonio LD, Richman JS, Carson AP, Lloyd-Jones DM, Howard G, Deng L, Howard VJ, Safford MM, Muntner P and Goff DC Jr., Performance of the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Pooled Cohort Risk Equations by Social Deprivation Status. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005676. doi: 10.1161/jaha.117.005676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brindle PM, McConnachie A, Upton MN, Hart CL, Davey Smith G and Watt GC. The accuracy of the Framingham risk-score in different socioeconomic groups: a prospective study. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:838–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiscella K, Tancredi D and Franks P. Adding socioeconomic status to Framingham scoring to reduce disparities in coronary risk assessment. Am Heart J. 2009;157:988–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, Rosal M and Yancy CW. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–98. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR and Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: Relationships Between Determinant Factors and Health Outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohm J, Skoglund PH, Discacciati A, Sundstrom J, Hambraeus K, Jernberg T and Svensson P. Socioeconomic status predicts second cardiovascular event in 29,226 survivors of a first myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:985–993. doi: 10.1177/2047487318766646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch CG, Li L, Kaplan GA, Wachterman J, Shishehbor MH, Sabik J and Blackstone EH. Socioeconomic position, not race, is linked to death after cardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:267–76. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.109.880377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch JW, Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Salonen R and Salonen JT. Does low socioeconomic status potentiate the effects of heightened cardiovascular responses to stress on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis? Am J Public Health. 1998;88:389–94. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, Ramey CT, Martin EK, Perry C, Reyes AAL and Vedamuthu IP. Social Determinants of Health in the United States: Addressing Major Health Inequality Trends for the Nation, 1935–2016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6:139–164. doi: 10.21106/ijma.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML and Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton JE, Perzynski AT, Zidar DA, Rothberg MB, Coulton CJ, Milinovich AT, Einstadter D, Karichu JK and Dawson NV. Accuracy of Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Varies by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Position: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:456–464. doi: 10.7326/m16-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Accessed December 29, 2019.

- 14.Giuse NB, Koonce TY, Kusnoor SV, Prather AA, Gottlieb LM, Huang LC, Phillips SE, Shyr Y, Adler NE and Stead WW. Institute of Medicine Measures of Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health: A Feasibility Study. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Risk Adjustment Information, including: Evaluation of the CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model, Model diagnosis codes, Risk adjustment model softeware, Information on customer support for risk adjustment. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Risk-Adjustors. Accessed 2019.

- 16.Fraze T, Lewis VA, Rodriguez HP and Fisher ES. Housing, Transportation, And Food: How ACOs Seek To Improve Population Health By Addressing Nonmedical Needs Of Patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2109–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagiwara N, Alderson CJ and Mezuk B. Differential Effects of Personal-Level vs Group-Level Racial Discrimination on Health among Black Americans. Ethn Dis. 2016;26:453–60. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang TC and Chen D. A multi-group path analysis of the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and self-rated stress: how does it vary across racial/ethnic groups? Ethn Health. 2018;23:249–275. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1258042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tawakol A, Osborne MT, Wang Y, Hammed B, Tung B, Patrich T, Oberfeld B, Ishai A, Shin LM, Nahrendorf M, Warner ET, Wasfy J, Fayad ZA, Koenen K, Ridker PM, Pitman RK and Armstrong KA. Stress-Associated Neurobiological Pathway Linking Socioeconomic Disparities to Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3243–3255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR. Stress and the Mental Health of Populations of Color: Advancing Our Understanding of Race-related Stressors. J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59:466–485. doi: 10.1177/0022146518814251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burroughs Pena MS, Mbassa RS, Slopen NB, Williams DR, Buring JE and Albert MA. Cumulative Psychosocial Stress and Ideal Cardiovascular Health in Older Women. Circulation. 2019;139:2012–2021. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.118.033915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond G and Joynt Maddox KE. A Theoretical Framework for Clinical Implementation of Social Determinants of Health. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:1189–1190. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winfield LD, DeSalvo K, Muhlestein D. Social Determinants Matter, But Who is Responsible? 2017 Physician Survey on Social Determinants of Health 2018. https://leavittpartners.com/whitepaper/social-determinants-matter-but-who-is-responsible/. Accessed September 26, 2019.

- 24.Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D and Adler NE. Integrating Social And Medical Data To Improve Population Health: Opportunities And Barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2116–2123. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraze TK, Brewster AL, Lewis VA, Beidler LB, Murray GF and Colla CH. Prevalence of Screening for Food Insecurity, Housing Instability, Utility Needs, Transportation Needs, and Interpersonal Violence by US Physician Practices and Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1911514. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.