We read with interest the study in the Journal by Chen and colleagues from Nanjing, China that demonstrated a high positivity rate (17%) in healthcare workers (HCWs),1 but did not attempt to breakdown which type of HCWs working in which specialties had the highest infection rates. Similarly, another study from Leicester, UK compared hospitalised and community patient SARS-CoV-2 PCR (polymerase chain reaction) positivity rates with that of staff,2 but again, did not assess which staff groups or clinical specialties were at most risk of acquiring COVID-19. Finally, one other study from Wuhan, China described the clinical features of HCWs infected with COVID-19, but again did not analyze the staff most infected by role or specialty.3

Here we present an analysis by role and specialty of symptomatic HCWs and their household contacts (total n = 207) that presented for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing, during the early part of the UK COVID-19 epidemic, between 17 March and 4 May 2020. During this period, the recommendations from Public Health England (PHE) were for any symptomatic HCW to self-isolate for at least 7 days, or for any individual (including HCWs) with symptomatic household contacts to self-quarantine for 14 days.4 To give some additional context, the UK went into lockdown on 23 March 2020,5 and all HCWs were required to wear some form of surgical mask or better in clinical areas on 26 March 2020.6

Healthcare workers (mean age: 38.2 years, s.d. 9.2, range 17–60 years) also presented with symptomatic household family members (mean age: 23.8 years, s.d. 16.5, range 2–45 years) for swabbing. The rationale for this at the time was that if neither the family contacts, nor the HCW were SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive, then the HCW could return to work earlier without being a SARS-CoV-2 risk to other HCWs or patients.

During this 7 week period, a total of 152 symptomatic and/or self-isolating HCWs (54 male: 98 female) with 55 home contacts (including spouses and children) presented for swabbing (a single combined nasal/throat swab). Of the 152 HCWs, 6 were Black, 99 were Asian, and 47 were of White ethnicity. The Ausdiagnostics SARS-CoV-2 PCR assay was used for this testing. This kit has a manufacturer's reported sensitivity of 97–98% and a specificity of 99–100%, which has been confirmed elsewhere.7

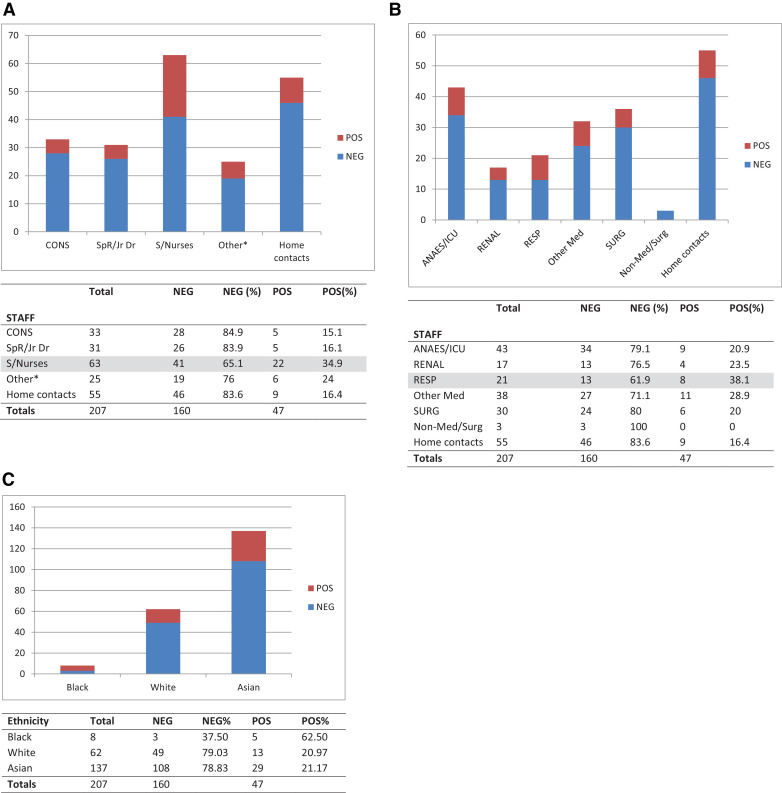

The results (Fig. 1 A) showed that the highest SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive rate (34.9%) was found in staff nurses compared to those (15–16%) for junior doctors, consultants and other support staff (24%, including healthcare assistants and those based in operating theatres, administration and estates). Of note, in this cohort, the home contact SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity rate (16.4%) was very similar to those in the non-staff nurse HCWs, at this stage of the COVID-19 epidemic in this cohort.

Fig. 1.

(A) Comparing positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR results in frontline staff by role. (B) Comparing positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR results in frontline staff by clinical specialty. (C) Comparing positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR results in HCWs and household contacts by ethnicity.

Fig. 1B illustrates the SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate in HCWs working in different clinical specialties, with those working in respiratory wards showing the highest positive rate (38.1%), followed by other medical specialties (28.9%), particularly the renal dialysis wards (23.5%), the adult intensive care unit (ICU) and anaesthetics (20.9%). The latter two specialties had a lot of overlap, with many anaesthetists also covering ICU, so these HCW totals were combined and plotted together.

These findings may not be entirely surprising as most suspected COVID-19 patients would be referred initially to the respiratory teams for assessment, and staff nurses are likely to spend more time with the patients on a more frequent basis, taking and recording bedside observations, administering drugs, and being the first HCWs on-site for any patient complications.

In addition, we compared the SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity rate against ethnicity for both the HCW and household contacts combined (Fig. 1C). This showed a high 62.5% (n = 8) positivity rate for Black individuals, though there were very few cases; and a similar 21.2% (n = 137) and 21.0% (n = 62) SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity rate for Asian and White individuals, respectively. These numbers are small and were obtained from the early part of the COVID-19 epidemic in the UK so it is not possible to recognize any specifically higher incidence of SARS-COV-2 infection in any of these BAME (Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic) groups.8

We then compared the SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity rates against various demographic parameters, ethnicity and symptom patterns in both the HCWs and household contacts (n = 47, Table 1 ). This showed that most of these positive cases were female (n = 29, 61.7%), Asian (n = 29, 61.7%), and aged 35 years or above (n = 31, 66.0%), with at least 1 systemic symptom (i.e. any of: fever, headache, myalgia or fatigue; n = 37, 78.7%); and at least 1 respiratory symptom (i.e. any of: cough, sore throat, shortness of breath or chest tightness/pain, n = 41, 87.2%). The mean duration from illness onset to specimen collection in these 47 SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive cases was 6.13 (s.d. 5.28) days.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 207 subjects stratified by SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results.

| Number of PCR POS cases (%) N = 47 | Number of PCR NEG cases (%) N = 160 | p-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 0–18 | 2 (4.3) | 27 (16.9) | 0.07 |

| 19–34 | 14 (29.8) | 56 (35.0) | |

| 35–44 | 18 (38.3) | 49 (30.7) | |

| 45 or above | 13 (27.7) | 28 (17.5) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 29 (61.7) | 92 (57.5) | 0.73 |

| Male | 18 (38.3) | 68 (42.5) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 13 (27.7) | 49 (30.7) | 0.02 |

| Asian | 29 (61.7) | 108 (67.5) | |

| Black | 5 (10.6) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Number of systemic symptomsa | |||

| 0 | 10 (21.3) | 65 (40.6) | 0.36 |

| 1 | 13 (27.7) | 43 (26.9) | |

| 2 | 6 (12.8) | 36 (22.5) | |

| 3–4 | 18 (38.3) | 16 (10.0) | |

| Number of respiratory symptomsb | |||

| 0 | 6 (12.8) | 45 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 21 (44.7) | 59 (36.9) | |

| 2 | 13 (27.6) | 39 (24.4) | |

| 3–5 | 7 (14.9) | 17 (10.6) | |

| Duration from symptom onset to specimen collection (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.13 (5.28) | NA | NA |

Systemic symptoms refer to any of: fever, headache, myalgia or fatigue.

Respiratory symptoms refer to any of: cough, sore throat, shortness of breath or chest tightness/pain.

Chi-squared test to test the null hypothesis of independence between two categorical variables.

An additional analysis was performed on the PCR positive cases where their sample Ct (cycle threshold) values were available (n = 39), using the same parameter categories as Table 1. This compared the Ct value (a relative indicator of viral load) against presenting symptom patterns. After adjusting for age, ethnicity, sex and time from symptom onset to specimen collection, it was found that the number of respiratory symptoms were positively associated with greater Ct values (i.e. lower viral loads, p< 0.01), while an increasing number of systemic symptoms was associated significantly with smaller Ct values (i.e. higher viral loads, p< 0.01) (Table S1). The mean duration from illness onset to specimen collection in these 39 SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive cases was 5.67 (s.d. 4.58) days.

This suggests that in this cohort, systemic symptoms may be more closely associated with the presence of higher viral loads, whereas respiratory symptoms may be more immune-mediated and can continue to persist during viral clearance. Other studies have found varying associations between symptom patterns, illness severity and viral loads,9 , 10 so additional studies are needed to understand better these host-virus interactions.

In summary, we have compared the SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity rates in this HCW and household contact cohort, across different clinical roles and specialties, ethnic groups, and explored the correlation between their symptom patterns and swab viral loads. Additional work is required to clarify further the relationships between these various parameters, such that dose-response monitoring can be applied in a rational manner when proven antiviral therapies for COVID-19 eventually become available.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.035.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Chen Y., Tong X., Wang J. High SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence among healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.067. in press. June 03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang J.W., Young S., May S., et al. Comparing hospitalised, community and staff COVID-19 infection rates during the early phase of the evolving COVID-19 epidemic. DOI: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chu J., Yang N., Wei Y. Clinical characteristics of 54 medical staff with COVID-19: a retrospective study in a single center in Wuhan. China J Med Virol. Jul 2020;92(7):807–813. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health England UK. Stay at Home guidance for households: current guidelines illustrated. 17 March 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/874011/Stay_at_home_guidance_diagram.pdf(Accessed 11 June 2020).

- 5.Public Health England UK. PM address to the nation on coronavirus: 23 March 2020. 23 March 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020(Accessed 11 June 2020).

- 6.Public Health England UK. Recommended PPE for healthcare workers by secondary care inpatient clinical setting, NHS and independent sector. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886707/T1_poster_Recommended_PPE_for_healthcare_workers_by_secondary_care_clinical_context.pdf(Accessed 11 June 2020).

- 7.Attwood L.O., Francis M.J., Hamblin J., Korman T.M., Druce J., Graham M. Clinical evaluation of AusDiagnostics SARS-CoV-2 multiplex tandem PCR assay. J Clin Virol. May 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khunti K., Singh A.K., Pareek M., Hanif W. Is ethnicity linked to incidence or outcomes of COVID-19? BMJ. Apr 2020;369:m1548. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. Mar 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu F., Yan L., Wang N. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. Mar 2020:ciaa345. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.