Abstract

Background

We present a case of pancreatic and splenic metastases following alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS), which was successfully treated by surgery.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old male was referred to our hospital in 2012. Computed tomography (CT) showed the presence of a pancreatic tumor. In 2002, the patient had undergone surgical resection of an ASPS of the anal region. In 2009, during follow-up, CT revealed lung metastases, which prompted surgical resection of the lung, followed by resection of the head skin in 2011. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed the presence of isodense masses sized 34 mm in the pancreatic head and 60 mm within the spleen. The contrast-enhanced US revealed a solitary lesion with enhancement. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed solitary lesions with enhancement within the pancreatic head, spleen, and liver. The patient underwent metastasectomies from the pancreas, spleen, and liver. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 22 without recurrence for 18 months after metastasectomy. Twelve years after primary resection and 2 years after metastasectomy, the patient died as a consequence of multiple metastases.

Conclusions

We have presented a rare case of pancreatic and spleen metastases from ASPS. Resection by radical metastasectomy was successful without morbidity. Thus, for improved survival of patients with multiple metastases from ASPS, metastasectomy may be indicated. If multiple metastases are resectable, surgical approaches may be the preferred treatment.

Keywords: Metastases, Pancreatic tumor, Metastasectomy, Alveolar soft part sarcoma

Background

In 1952, alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) was reported for the first time by Christopherson, Foote, and Stwart [1]. ASPS is a rare tumor, which accounts for 0.5–1% of soft tissue sarcomas [2]. ASPS has been characterized as growing more slowly than other types of sarcoma, with a peak incidence around 30 years of age [2]. Occurrence sites are mostly in the extremities, thighs (41%), pelvis/iliac fossa (10%), and upper limbs (9%) [3]. Metastasis occurs in about 15–30% of cases, mainly at sites in the lungs, bones, and lymph nodes [3]. Metastases located elsewhere are rare, and to our knowledge, cases of ASPS with pancreatic and splenic metastases have thus far not been reported. Here, we present a case of ASPS that was successfully treated by resection of pancreatic and splenic metastases performed as elective procedures.

Case presentation

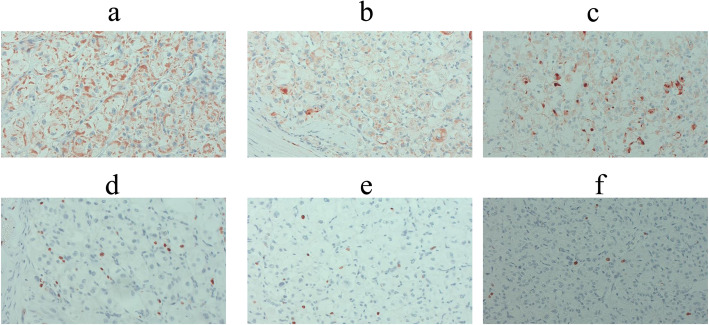

A 41-year-old man who had undergone surgical resection of an ASPS of the anal region 10 years earlier presented to our hospital in 2012 because of a tumor of the pancreatic head detected via computed tomography (CT) during follow-up. In 2009, during follow-up, CT indicated lung metastasis. The patient underwent surgical resection of the lung, and in 2011, resection of the head skin was related to the metastasis. The abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed the presence of isodense masses of 34 mm in the pancreatic head and 60 mm in the spleen. US with contrast revealed solitary lesions with enhancement (Fig. 1a, b). Contrast-enhanced CT revealed solitary lesions with enhancement located in the pancreatic head, spleen, and liver (Fig. 2a–c). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed no stenosis of the pancreatic duct. Blood examinations revealed low hemoglobin (Hb) (12.3 g/dl), low hematocrit (Ht) (24.3%), and low total protein levels (6.6 g/dl). No further laboratory tests, including those for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), showed abnormal values. The patient was diagnosed with a neuroendocrine tumor or pancreatic metastasis of ASPS. Subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (SSPPD) of the pancreatic head mass, resection of the spleen, and partial hepatectomy were performed. The operative time was 616 min, and the blood loss was approximately 1070 g. Gross examination revealed that the excision cut of the tumor was gray, and 40 mm in size, with a clear border between the tumor and pancreas. The excision margin of the spleen tumor was gray, 60 mm in size, and showed a clear border between the tumor and spleen. The excision cut of the liver tumor was yellow, 10 mm in size, and showed an unclear border between the tumor and liver. The pathological examination showed that atypical cells with eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules proliferated to form solid alveolar nests in both pancreas and spleen (Fig. 3a–h). Further examination showed focal nodular hyperplasia in the liver; immunohistochemistry analysis in primary ASPS and pancreatic and splenic metastases (Fig. 4a–f). Primary ASPS, pancreatic, and splenic metastases had Desmin-positive foci. The antigen Ki-67 proliferation index was < 10% in primary ASPS, pancreatic, and splenic metastases. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 22. However, the patient showed recurrence of multiple lung metastases at 18 months after metastasectomy. Twelve years after primary resection and 2 years after metastasectomy, the patient died as a consequence of multiple metastases.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) with and without contrast. Abdominal US with and without contrast revealed the presence of isodense masses of 34 mm (a) in the pancreatic head and 60 mm and in the spleen (b) (arrows)

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (horizontal slice). Contrast-enhanced CT revealed solitary lesions with enhancement in the liver (a), spleen (b), and pancreatic head (c) (arrow)

Fig. 3.

Findings of the resected specimen. The macroscopic and microscopic findings of the cut specimen revealed gray and clear borders between the tumor and pancreas (a, b) and spleen (c, d), and yellow and unclear border between the tumor and liver. Pathological examination showed that atypical cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm had proliferated to form alveolar solid nests in the pancreas (e, f) and spleen (g, h). The pathological examination further showed focal nodular hyperplasia at the liver

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry analysis in primary ASPS, and pancreatic and splenic metastases (Desmin and Ki-67 original magnification x 200). Primary ASPS (a), pancreatic metastases (b), and splenic metastases (c) had Desmin-positive foci. The antigen Ki-67 proliferation index was < 10% in primary ASPS (d), pancreatic metastases (e), and splenic metastases (f)

Conclusions

Overall, the patient survived primary resection of ASPS for 12 years, primary metastases for 8 years, and pancreatic and splenic metastases resection for 2 years. This noteworthy outcome of this case of metastatic ASPS was obtained by virtue of repeated operations on metastases that emerged over time.

A prior study of autopsied cases showed a prevalence of pancreatic metastases of 11.6% [4]. Pancreatic metastasis accounts for less than 2% of all pancreatic malignancies [5]. Specifically, the primary diseases of patients undergoing pancreatic metastasectomy were renal cell cancer in 61.7%, colon cancer in 7.8%, melanoma in 4.9%, and sarcoma in 4.9% of cases [5]. Pancreatic metastasis usually exhibits few symptoms and are often discovered by chance during follow-up examinations. However, their characterization is usually poorly defined, often reflecting the characteristic of the primary disease. Contrast-enhanced CT scans are required to distinguish the metastases from diseases such as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, acinar cell tumors, and others. It is necessary to confirm the clinical course, including the history and dynamics of the pancreatic hormones. EUS-FNAB is useful to establish a differential diagnosis, however should be used with caution because of the risk of bleeding, infection, pancreatitis, and dissemination. In this case, EUS-FNAB was not performed, because the clinical course of the patient suggested a metastatic lesion. At the time of metastatic pancreatic tumor detection, lymph node metastases have been reported in 33–38% of cases [6]. The metastatic forms of ASPS show hematogenous, lymphatic, and peritoneal dissemination. The frequency is often hematogenous metastasis, lung (63%), brain (19%), and bone (6%) [3]. Lymphatic metastasis is 2–7% [3, 7]. Common surgical procedures to treat pancreatic metastatic tumors include pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), distal and middle pancreatectomy, total resection, and enucleation. However, the recurrence rate after atypical resection, such as enucleation, middle pancreatectomy, and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection, of pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma is 50% [8]. It is generally assumed that a typical operation, such as PD and distal pancreatectomy, provides better treatment outcomes for pancreatic metastases [5]. The prognosis depends on the primary disease type. The average survival is about 4 months without surgical resection of ASPS, and the 5-year survival rate was about 20% [3]. Indications for resection of pancreatic metastases include their originating from primary renal cell carcinoma, a prolonged disease-free interval, and the absence of extra-pancreatic metastases [9]. We think, however, that surgical procedures could be selected whenever resection is possible and when the performance status of the patient was good after undergoing resection.

Pazopanib is an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor signaling [10]. In a study examining the efficacy of pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE) study in metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 4.6 months, compared to 1.6 months in the placebo group [11]. In a phase 2 trial in patients with metastatic ASPS, the partial response rate following pazopanib was 16.7%, whereas the median PFS was 5.5 months [12]. Thus, because there no established chemotherapy that exists for these cases yet, surgical procedures are still the mainstay of treatment providing the best chance for long-term survival [13, 14]. Many metastases of ASPS occur in the lungs. The overall survival (OS) with resected lung metastases of ASPS amounts to 218 months, compared to about 63.5 months without resection [15]. However, it is not a statistical proof as it is a study of five patients resected and twelve patients unresected [15]. In 2015, median survival after the diagnosis of lung metastases was 34 months, and a 5-year survival rate was 64.1% for patients with lung metastases [16]. However, complete pulmonary metastasectomy has better survival than unresectable (3 years OS 32% vs. < 20%) [17]. Also, wide resection for local recurrence has better survival than unresectable (3 years OS 86% vs. 67%) [18]. In the literature in English, metastasectomies of the lung, brain, and local have shown favorable results with prolonged survival in selected patients [3, 14, 19–31] (Table 1). The pulmonary metastasectomy cases survived 60–132 months [3, 14, 19–22]. The local resection cases survived 6–300 months [14, 23, 24]. The brain metastasectomy cases survived 6–142 months [27–31]. Among the cases performed after metastasectomy, recurrence was found 2–240 months later. Long-term recurrence was 96 months at local [19] and 240 months at distant metastases [27]. The progression of ASPS is more slowly than other types of sarcoma [2]. Although pazopanib was not administered during the treatment of the present case, surgical procedures may be more effective if metastases can be removed. Here, we first report on the effect of metastasectomy of pancreatic and splenic metastases of ASPS.

Table 1.

Characteristic of metastasectomy in case reports

| author | Age | Sex | Primary site | Metastases at present | Metastases resection | Local therapy (Primary site) |

RT | CT | Periods until recurrence (months) |

Site of metastasis | Laterality | single / multiple | metastasectomy | RT | CT | Survival postmetastasectomy (month) |

status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baum ES [19] | 14 | M | Upper extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | 96 | Lung | bilateral | multiple | Pulmonectomy | No | Yes | 60 | NED |

| Evans HL [20] | 7 | F | Scapula | - | - | Exision | Yes | No | 40 | Lung | bilateral | multiple | Pulmonectomy | No | Yes | 69 | NED |

| Kodama K [21] | 23 | F | Lower extremity | Lung | resection | Exision | No | Yes | - | Lung | bilateral | multiple | Pulmonectomy | No | No | 98 | NED |

| Portera CA [3] | - | - | unknown | Lung | resection | Exision | No | Yes | - | Lung | unknown | multiple | Pulmonectomy | No | Yes | 132 | NED |

| Sidi V [22] | 11 | M | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | Yes | Yes | 8 | Lung | bilateral | multiple | Pulmonectomy | Yes | Yes | 60 | NED |

| van Ruth S [14] | 22 | F | Lower extremity | Lung | unknown | unknown | unknown | Yes | - | Lung | bilateral | multiple | Hepatectomy and nephrectomy | No | Yes | 111 | DOD |

| 18 | F | Head and neck region (left temple) | - | - | Exision | Yes | No | 36 | Local | - | single | Exision | No | No | 300 | NED | |

| Emmez H [23] | 11 | F | Head and neck region (left frontal lobe) | - | - | Exision | No | No | 6 | Local | - | single | Exision | Yes | Yes | 6 | NED |

| Wang Y [24] | 9 | F | Head and neck region (left eye) | - | - | Exision | Yes | No | 84 | Local | - | single | Exision | Yes | No | 131 | DOD |

| 12 | F | Head and neck region (left eye) | - | - | Exision | No | No | 2 | Local | - | single | Exision | Yes | No | 36 | NED | |

| 1 | M | Head and neck region (left eye) | - | - | Exision | No | No | 96 | Local | - | single | Exision | Yes | No | - | NED | |

| Wang M [25] | 39 | F | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | 120 | Lung+brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | Yes | Yes | 8 | AWD |

| Daigeler A [26] | 40 | M | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | 9 | Lung+brain | unknown | unknown | Exision | Yes | Yes | 48 | DOD |

| 21 | M | Upper extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | 12 | Lung+brain | unknown | unknown | Exision | Yes | Yes | 79 | DOD | |

| 48 | M | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | 7 | Lung+brain+local | unknown | unknown | Exision | Yes | Yes | 97 | DOD | |

| Ohashi H [27] | 25 | F | Buttock | - | - | Exision | No | No | 240 | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 142 | DOD |

| Wronski M [28] | 14 | F | Lower extremity | Lung | resection | Exision | No | unknown | 23 | Brain | - | unknown | Craniotomy | No | No | 73 | DOD |

| 7 | M | Head and neck region (tongue) | Lung | resection | Exision | No | unknown | 23 | Brain | - | unknown | Craniotomy | No | No | 23 | DOD | |

| Ogose A [29] | 61 | M | Lower extremity | Lung, bone, bowel | unknown | Exision | No | unknown | 84 | Brain | - | unknown | Craniotomy | No | No | 24 | DOD |

| Tao X [30] | 22 | M | Upper extremity | Lung | unknown | Exision | No | Yes | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 69 | AWD |

| 15 | F | Chest | Lung | unknown | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 35 | AWD | |

| 26 | F | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | Yes | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 32 | NED | |

| 32 | M | Lower extremity | Lung | unknown | Exision | Yes | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 31 | NED | |

| 25 | M | Crus | Lung | unknown | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 20 | DOD | |

| 33 | M | Lower extremity | Lung | unknown | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 25 | AWD | |

| 26 | M | Lower extremity | - | - | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 14 | NED | |

| 23 | M | Trunk/retroperitoneal/abdomen | - | - | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | unilateral | single | Craniotomy | No | No | 6 | NED | |

| Kaushal-Deep SM [31] | 20 | M | Lower extremity | Brain | resection | Exision | No | No | - | Brain | bilateral | multiple | Craniotomy | Yes | Yes | 12 | AWD |

CT chemotherapy, RT radiotherapy, DOD dead of disease, NED no evidence of disease, AWD alive with disease

In conclusion, we have presented a rare case of pancreatic and splenic metastases originating from ASPS. Radical metastasectomy by resection was performed successfully. Multiple metastases related to ASPS support the possibility that metastasectomy is associated with improved overall survival. If multiple metastases are found to be resectable, this procedure may be favorable candidates as part of surgical treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that this study was not funded externally. The authors would like to thank MARUZEN-YUSHODO Co., Ltd. (https://kw.maruzen.co.jp/kousei-honyaku/) for the English language editing.

Abbreviations

- ASPS

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

- CA19-9

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CT

Computed tomography

- EUS-FNAB

Endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration biopsy

- MRCP

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- PD

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- SSPPD

Subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy

- US

Ultrasonography

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

SA wrote the manuscript. The remaining authors contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the study’s concept, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The patient data for this case report will not be shared to ensure patient confidentiality.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complied the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. IRB approval was exempted because this was only a case report. Parental consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of the case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Christopherson WM, Foote FW, Jr, Stewart FW. Alveolar soft part sarcomas: structurally characteristic tumors of uncertain histogenesis. Cancer. 1952;5:100–111. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195201)5:1<100::AID-CNCR2820050112>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Malignant tumors uncertain type. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Soft tissue tumors. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 1067–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portera CA, Ho V, Patel SR, Hunt KK, Feig BW, Respondek PM, et al. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: clinical course and patterns of metastasis in 70 patients treated. Cancer. 2001;91:585–591. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010201)91:3<585::AID-CNCR1038>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams HL, Spiro R, Goldstein N. Metastasis in carcinoma. Analysis of 1000 autopsied cases. Cancer. 1950;3:74–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<74::AID-CNCR2820030111>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:287–293. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Berselli M, Frison L, Vicario G, Pedrazzoli S. Metastasis to the pancreas from colorectal cancer: is there a place for pancreatic resection? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1154–1159. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819f7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieberman PH, Foote FW, Jr, Stewart FW, Berg JW. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma. JAMA. 1966;198:1047–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.1966.03110230063012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassi C, Butturini G, Falconi M, Sargenti M, Mantovani W, Pederzoli P. High recurrence rate after atypical resection pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:555–559. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strobel O, Hackert T, Hartwig W, Bergmann F, Hinz U, Wente MN, et al. Survival data justifies resection for pancreatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3340–3349. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schutz FA, Choueiri TK, Sternberg CN. Pazopanib: clinical development of a potent anti-angiogenic drug. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim M, Kim TM, Keam B, Kim YJ, Paeng JC, Moon KC, et al. A phase II trial of pazopanib in patients with metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma. Oncologist. 2019;24:20–29. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappo AS, Parham DM, Cain A, Luo X, Bowman LC, Furman WL, et al. Alveolar soft part sarcoma in children and adolescents: clinical features and outcome of 11 patients. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;26:81–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199602)26:2<81::AID-MPO2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Ruth S, van Coevorden F, Peterse JL, Kroon BB. Alveolar soft part sarcoma. A report of 15 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1324–1328. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberman PH, Brenann MF, Kimmel M, Erlandson RA, Garin-Chesa P, Flehinger BY. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma. A clinico-pathologic study of half a century. Cancer. 1989;63:1–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<1::AID-CNCR2820630102>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu YP, Wang WH, Wang SL, Song YW, Fang H, Ren H, Liu XF, Yu ZH, Li YX. A retrospective analysis of lung metastasis in 64 patients with alveolar soft part sarcoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:803–809. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putnam JB, Roth JA, Wesley MN, Johnston MR, Rosenberg SA. Analysis of prognostic factors in patients undergoing resection of pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;87:260–268. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)37420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennacchioli E, Fiore M, Collini P, Radaelli S, Dileo P, Stacchiotti S, Casali PG, Gronchi A. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in a series of 33 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:322–333. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baum ES, Fickenscher L, Nachman JB, Idriss F. Pulmonary resection and chemotherapy for metastatic alveolar soft-part sarcoma. Cancer. 1981;47:1946–1948. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810415)47:8<1946::AID-CNCR2820470805>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans HL. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma. Cancer. 1985;55:912–917. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<912::AID-CNCR2820550434>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama K, Doi O, Higashiyama M, Yokouchi H, Kuriyama K, Ueda T, Yoshikawa H. Surgery for multiple lung metastases from alveolar soft-part sarcoma. Surg Today. 1997;27:806–811. doi: 10.1007/BF02385270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidi V, Fragandrea I, Hatzipantelis E, Kyriakopoulos C, Papanikolaou A, Bandouraki M, Koliouskas DE. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the extremity: a case report. Hippokaratia. 2008;12:251–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emmez H, Kale A, Celik S, Borcek AO, Yilmaz G, Kaymaz M, Uluoglu O, Pasaoglu A. Primary intracerebral alveolar soft part sarcoma in an 11-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. NMC Case Rep J. 2015;1:31–35. doi: 10.2176/nmccrj.2014-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Du B, Yang M, He W. Paediatric orbital alveolar soft part sarcoma recurrence during long-term follow-up: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20:60. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-1312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Li J, Huan L, Meng F, Pang Q. Alveolar soft part sarcoma associated with lung and brain metastases: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:956–958. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daigeler A, Kuhnen C, Hauser J, Goertz O, Tilkorn D, Steinstraesser L, Steinau HU, Lehnhardt M. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: clinicopathological findings in a series of II cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohashi H, Sakata K, Ueda S, Sakamoto T, Miwa M. Cerebral metastasis of alveolar soft-part sarcoma report of a case of long postoperative survival. Arch Jap Chir. 1974;43:379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wronski M, Arbit E, Burt M, Perino G, Galicich JH, Brennan MF. Resection of brain metastases from sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:392–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02306371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogose A, Morita T, Hotta T, Kobayashi H, Otsuka H, Hirata Y, Yoshida S. Brain metastases in musculoskeletal sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:245–247. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.5.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao X, Hou Z, Wu Z, Hao S, Liu B. Brain metastatic alveolar soft-part sarcoma: clinicopathological profiles, management and outcomes. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:5779–5784. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaushal-Deep SM, Raswan US, Kirmani AR, Bhat AR, Bhat IH. Alveolar soft part sarcoma metastasizing to the brain: a rare entity revisited with review of resent literature. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2019;14:158–161. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_52_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The patient data for this case report will not be shared to ensure patient confidentiality.