Abstract

Damage to joints through injury or disease can result in cartilage loss, which if left untreated can lead to inflammation and ultimately osteoarthritis. There is currently no cure for osteoarthritis and management focusses on symptom control. End-stage osteoarthritis can be debilitating and ultimately requires joint replacement in order to maintain function. Therefore, there is growing interest in innovative therapies for cartilage repair. In this systematic literature review, we sought to explore the in vivo evidence for the use of human Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived Extracellular Vesicles (MSC-EVs) for treating cartilage damage. We conducted a systematic literature review in accordance with the PRISMA protocol on the evidence for the treatment of cartilage damage using human MSC-EVs. Studies examining in vivo models of cartilage damage were included. A risk of bias analysis of the studies was conducted using the SYRCLE tool. Ten case-control studies were identified in our review, including a total of 159 murine subjects. MSC-EVs were harvested from a variety of human tissues. Five studies induced osteoarthritis, including cartilage loss through surgical joint destabilization, two studies directly created osteochondral lesions and three studies used collagenase to cause cartilage loss. All studies in this review reported reduced cartilage loss following treatment with MSC-EVs, and without significant complications. We conclude that transplantation of MSC-derived EVs into damaged cartilage can effectively reduce cartilage loss in murine models of cartilage injury. Additional randomized studies in animal models that recapitulates human osteoarthritis will be necessary in order to establish findings that inform clinical safety in humans.

Keywords: extracellular vesicle, mesenchymal stem cell, cartilage, tissue engineering, osteoarthritis

Introduction

Damage to joints through injury or disease can result in cartilage loss, which if left untreated can lead to inflammation and ultimately osteoarthritis (OA) (Davies-Tuck et al., 2008). OA affects up to three out of 10 people over the age of 60 years (Woolf and Pfleger, 2003), and this is projected to increase substantially (Turkiewicz et al., 2014). There is currently no cure for OA and management is focused on symptom control (Mcalindon et al., 2014). Furthermore, the search for Disease Modifying Osteoarthritis Drugs (DMOAD) has not been fruitful, and there are no approved DMOADs. End-stage OA can be severely debilitating and ultimately requires joint replacement in order to maintain function (Gillam et al., 2013). Joint replacement is costly and carries perioperative morbidity (Berstock et al., 2014) as well as unsatisfactory outcomes (Nilsdotter et al., 2003). Therefore, there is a need for innovative therapies to treat cartilage defects and in doing so, prevent OA.

The established treatment of microfracture for focal cartilage defects aims to encourage endogenous cells to repopulate areas of cartilage loss, but this has demonstrated limited effectiveness (Weber et al., 2018). A large number of studies have investigated tissue engineering and cellular regenerative approaches to treating cartilage defects (Negoro et al., 2018). Acellular biomaterial scaffolds are costly to develop and implantation of these scaffolds into cartilage defects exhibits a high failure rate (Vindas Bolaños et al., 2017). Certain cell-based approaches such as Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) can be effective but cause donor-site morbidity (Reddy et al., 2007; Bexkens et al., 2017). Recently, there has been an increasing body of evidence to support the use of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in cartilage repair (Borakati et al., 2018).

MSCs are multipotent adult stromal cells that may be derived from a number of tissues including bone marrow, synovium, adipose, umbilical cord and dental pulp, and so are readily available for autologous harvest (Fernandes et al., 2018; Fabre et al., 2019). Ease of extraction and the potential for ex vivo expansion make MSCs an attractive option for tissue repair. To this end, studies have shown the therapeutic potential of MSC transplantation in promoting regeneration of tissues such as bone, cartilage, and nerve (Katagiri et al., 2017; Freitag et al., 2019; Masgutov et al., 2019). However, MSC transplantation is not without risks. Certain studies have revealed potential immunogenic complications related to repeated allogenic transplantation of MSCs (Cho et al., 2008) and others have reported possible tumorigenic properties (Beckermann et al., 2008). There is also in vivo evidence to suggest that, when transplanted in the presence of malignancy, MSCs may increase the risk of metastasis (Karnoub et al., 2007). Suboptimal engraftment and delocalization from the target site create difficulty in maintaining sustained benefit following transplantation, and suggest that observed long-term benefits may not result from MSC differentiation alone (Zwolanek et al., 2017).

Increasingly so, studies are focussing on the paracrine function of MSCs as the predominant mechanism of their regenerative effects (Linero and Chaparro, 2014; Xu et al., 2016). MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) are gaining interest as a cell-free therapeutic option for cartilage repair. As part of MSC secretome, EVs are nanovesicles ranging from 10 nm to several micrometers that contain various components including genetic material in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), lipids and bioactive proteins (Di Vizio et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2017; Théry et al., 2018). MSC-EVs are characterized by cell-surface expression of generic EV markers such as CD9, CD81, CD82, TSG101, and Alix. Transplantation of MSC-EVs may carry certain advantages over cell-based therapies. Firstly, accurate quantification of number of transplanted MSCs may be difficult and their effects could also be less predictable than that of EVs within the recipient site, potentially making outcomes of clinical trials less reproducible. Production costs of EVs at a large scale could be lower than that of MSCs (Cha et al., 2018). Furthermore, EVs exert low potential for toxicity and immunogenicity with repeated transplantation (Zhu X. et al., 2017; Saleh et al., 2019), and therefore avoid the undesired immunogenic properties of MSCs (Gu et al., 2015). As a cell-free therapy, MSC-EVs can be stored by cryopreservation whereas MSCs cannot, and therefore have greater potential as an off-the-shelf treatment option (Vlassov et al., 2012).

Through mechanisms including direct receptor interaction, membrane fusion, and internalization, EVs are able to influence recipient cell behavior to promote a variety of effects relevant to cartilage repair. In vitro evidence shows that MSC-EVs exert anti-inflammatory effects through influencing IL-6 and TGF-β secretion by dendritic cells. Furthermore, MSC-EVs are found to contain miRNAs such as miR-21-5p which target the CCR7 gene for degradation (Reis et al., 2018) and non-coding RNA that mediate an anti-inflammatory response (Fatima et al., 2017). Co-culture of MSCs with chondrocytes is found to promote matrix production and chondrocyte chondrogenesis in vitro, and these effects appear to be EV-dependent (Kim et al., 2019). In vitro studies also suggest that chondrocytes take-up MSC-EVs that upregulate type II collagen production (Vonk et al., 2018). Finally, results of recent ex vivo studies have suggested that MSC-conditioned media is able to downregulate the expression of genes that promote extra-cellular matrix degradation such as MMP1, MMP13, and IL-1β in synovial explants (van Buul et al., 2012) facilitating cartilage repair, suggesting a role for EVs (Nawaz et al., 2018).

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the use of MSC-EVs in cartilage repair and some systematic reviews have examined the in vitro evidence for animal MSC-EVs. In this systematic literature review, we sought to explore the in vivo evidence for the use of human-derived MSC-EVs in murine models of cartilage repair.

Materials and Methods

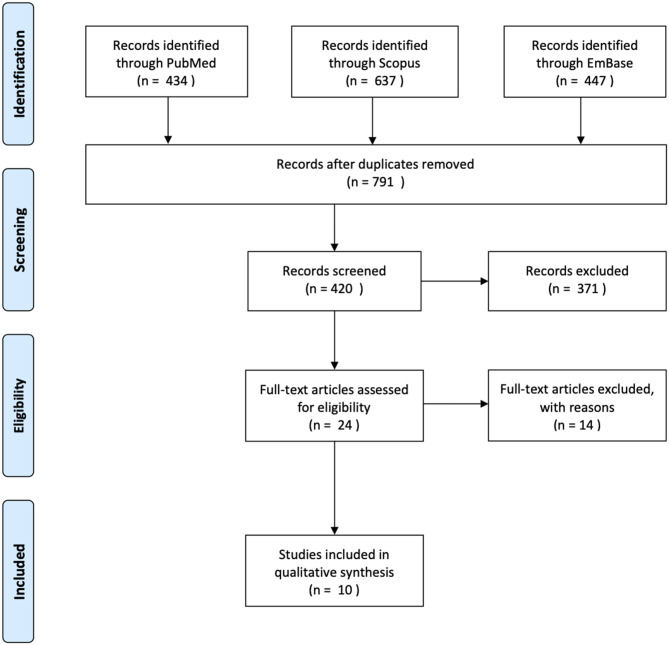

The methods used to conduct this review were according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement protocol (Moher et al., 2015). We carried out a literature search on PubMed, Scopus, and EmBase databases in January 2020, capturing articles starting from conception. The following search strategy was applied: (Mesenchymal stem cell OR MSC* OR Multipotent stromal cell OR Multipotent stem cell OR Mesenchymal stromal cell) AND (Extra-cellular vesicle OR extracellular vesicle OR EV* OR exosomal OR exosome) AND (osteoarthritis OR OA* OR osteochondral OR Cartilage). Following de-duplication, exclusion criteria was applied to studies not written in or translated into the English language. We excluded studies that only performed in vitro experiments. Studies that did not characterize or validate the cell populations as per the recommendations of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) for MSC were excluded (Witwer et al., 2019). We included studies that examined the effects of human MSC-derived exosomes, studies examining animal MSC-derived exosomes were excluded. Studies that conducted characterization of EVs in accordance with The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) standards were included (Théry et al., 2018). We included case-control studies, randomized control trials, case series, and case reports with two or more subjects. After removing duplicates, a total of 727 studies underwent title screening (Figure 1). A total of 24 studies were examined in full text. Ten studies were included in our review.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Quality assessment was carried out independently KR and CM using the SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool (Hooijmans et al., 2014), discrepancies in results were resolved by discussion.

Results

MSC Characteristics

We identified 10 studies in our review, all of which were case-control studies with murine subjects. MSCs were derived from a variety of human tissue sources (Table 1). Four studies (Wang et al., 2017), three by the same group, used MSCs derived from embryonic stem cells (Zhang et al., 2016, 2018, 2019). Three studies obtained MSCs from bone marrow aspirate (Khatab et al., 2018; Mao et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2020), one from infrapatellar fat pad (Wu et al., 2019) and one from synovial tissue (Tao et al., 2017). One study compared EVs from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPS)-derived MSCs with synovium-derived MSCs (Zhu Y. et al., 2017). All MSCs were characterized using flow cytometry and trilineage differentiation. All MSCs expressed either CD44, CD90 or CD105, and most expressed low levels of HLA-DR.

Table 1.

Method of MSC harvest and characterization.

| References | Source | Cell harvest | Cell treatment | MSC characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khatab et al. (2018) | Human | Heparinised femoral shaft bone marrow aspirate | Cultured in minimal essential medium alpha (α MEM), Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) and Invitrogen to third passage | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD73, CD90, CD105, CD166 +ve |

| Mao et al. (2018) | Human | Bone marrow aspirate from iliac crest | Cultured in astandard Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) media and changed to chondrogenic media from third passage onwards. miR-92a-3p overexpressed in one group | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD11b, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD73, CD90, CD105, and HLA-DR –ve |

| Tao et al. (2017) | Human | Synovial membrane tissue | Cultured in standard MSC media to fifth passage. miR-140-5p overexpressed in one group | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD151 +ve |

| Wang et al. (2017) | Human | Embryonic stem cell-derived MSCs (obtained from third party) | Cultured in standard MSC media and cells between fourth and seventh passage were utilized | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD73, CD90, CD105 +ve |

| Wu et al. (2019) | Human | Infrapatellar fat pad obtained following total knee arthroplasty | Cultured in standard MSC media to confluence and used at first passage | Flow Cytometry: CD44, CD73, CD90 +ve. CD34, CD11b, CD19, CD45, HLA-DR present at low levels |

| Zhang et al. (2016) | Human | Cleavage and blastocyst- stage embryonic stem cells from in vitro fertilization | Cultured in standard MSC media. Further details not stated | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD105, CD24 +ve |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Human | Immortalized E1-Myc 16.3 embryonic stem cell-derived MSC | Cultured in standard MSC media and passaged at 80% confluence until use. Grown in defined media for 3 days prior to exosome extraction | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105 +ve, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR –ve |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | Human | Immortalized E1-Myc 16.3 embryonic stem cell-derived MSC | Cultured in standard MSC media and passaged at 80% confluence until use. Grown in defined media for 3 days prior to exosome extraction | Trilineage differentiation, Flow cytometry: CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105 +ve, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR –ve |

| Zhu Y. et al. (2017) | Human | Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSC (iMSC) induced from human umbilical cord iPS Synovial MSC (sMSC) from humans undergoing Anterior crucial efforts ligament (ACL) reconstruction |

iMSC: iPS cultured for 5 days in mTESR1 (Stemcell) and then cultured in standard MSC media for 2 weeks. The cells were then passaged every 5–7 days until a fibroblastic morphology was adopted sMSC: cultured in standard MSC media, with media changed every 4 days |

Trilineage differentiation Flow cytometry: iMSC: CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90 +ve. CD34, CD45, HLA-DR –ve sMSC: CD44, CD73, CD90, CD166 +ve. CD34, CD4, HLA-DR –ve |

| Jin et al. (2020) | Human | MSCs derived from bone marrow aspirate from the ilium of healthy subjects | Cultured to third to fifth passage with media changed every 48 h | Trilineage differentiation. Flow cytometry: CD29, CD44, CD71 +ve. CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR -ve |

refers to individual culture condition protocol without addition of stimulating factors.

EV Characteristics

Ultracentrifugation and ultrafiltration were the two most common methods for isolation of exosomes (Table 2). One study used polyethylene glycol precipitation as part of the purification process (Wu et al., 2019), and several used tangential flow filtration (TFF). EV dimensions were determined using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) in all but one study (Khatab et al., 2018). EV size ranged from 30 to 200 nm, with a modal mean size of around 100 nm. Flow cytometry and western blotting were standard methods for characterizing EVs. CD9, CD63, CD81, and ALIX were the most common EV markers identified. Five out of 10 studies that determined the bioactive component of the EVs used with Reverse Transcriptase quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) or Western blot analysis. Three studies attributed the effects of EVs to various miRNA. Two studies determined that CD73-mediated protein kinase activation was responsible for the in vivo effects of EV transplantation (Zhang et al., 2018, 2019).

Table 2.

Method of EV purification and characterization.

| References | Purification process | EV dimensions | EV marker | Imaging | Active component |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khatab et al. (2018) | Ultracentrifugation | Not determined | Not determined | Not utilized | Not determined |

| Mao et al. (2018) | Ultracentrifugation | 50–150 nm | CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70 | Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) | miR-92a-3p |

| Tao et al. (2017) | Not specified | 30–150 nm | CD63, CD9, CD81, ALIX | TEM, DLS | Not determined |

| Wang et al. (2017) | Ultracentrifugation | 30–200 nm | CD63, CD9 | TEM | Not determined |

| Wu et al. (2019) | Ultrafiltration and polyethylene glycol precipitation | 30–150 nm, main peak at 125.9 nm | CD9, CD63, CD81 | TEM | miR-199-3p, miR-99-5p, MiR-100-5p (targeting 3'UTR of mTOR) |

| Zhang et al. (2016) | Culture media concentrated by Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) sequentially through membranes (1,000 kDa, 500 kDa, 300 kDa, and 100 kDa) then filtered through 0.2 um filter | Homogenously sized particles; modal size of 100 nm | CD81, TSG101, ALIX | TEM | Not determined |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Conditioned medium was size fractionated and concentrated by TFF | Homogenously sized particles; modal size of 100 nm | CD81, TSG101, ALIX | TEM | CD73-mediated adenosine activation of MAPK signaling |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | Conditioned medium was sized fractionated and concentrated by TFF | Particles between 100 and 200 nm | CD81, TSG101, ALIX | TEM | CD73 mediated activation of MAPK signaling |

| Zhu X. et al. (2017) | Conditioned media concentrated by centrifugation and ultrafiltration | Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS): 50–150 nm TEM: 50–200 nm |

CD9, CD63, TSG101 | TEM, TRPS | Not determined |

| Jin et al. (2020) | Conditioned media extracted using size fractionation and filtration | 50–100 nm | CD63, CD9, Hsp70 | TEM | miR-26a-5p |

Animal Models

All studies used murine models; five studies induced osteoarthritis, including cartilage loss through surgical joint destabilization, two studies directly created osteochondral lesions and three studies used collagenase to cause cartilage loss. All but one study, which examined the TMJ, studied the knee joint. Follow-up duration ranged from 3 to 12 weeks after induction of cartilage injury. All studies delivered EVs via intra-articular injection. No significant side-effects were reported in any subjects. Varying amounts of EVs were used between studies, and the amount was quantified using different measures (Table 3). Some studies injected a given volume with a known concentration of EVs, whereas others determined the mass of EVs delivered.

Table 3.

Summary of findings from in vivo experiments.

| References | Method of delivery | Injury model | Duration of follow up | Macroscopic appearance/functional studies | Imaging and histology | Biochemical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khatab et al. (2018) | Intra-articular injection of secretome (Derived from 20,000 third passage MSCs suspended in 6 μl medium) on day 7, 9, and 11 after OA induction | Murine, Collagenase Induced Osteoarthritis (CIOA) | 21 days | Greater pain reduction in OA-affected limb from day 7 in treated groups | Histological assessment revealed improved cartilage thickness but no treatment effect on subchondral bone volume | Immunostaining of iNOS, CD163, and CD206 did not demonstrate a difference between treated and untreated groups |

| Mao et al. (2018) | Intra-articular injection of 15 μl of MSC-derived exosomes or MSC-derived exosomes from a group pre-treated with miR-92a-3p-Exos On days 7, 14, and 21 | Murine, CIOA | 28 days | Improved cartilage appearance in treated groups | Improved microscopic cartilage matrix appearance | Greater COL2a1 and aggrecan staining in treated lesions. Increased regulation of WNT5A, COL2A1, and aggrecan mRNA expression |

| Tao et al. (2017) | Intra-articular injection of 100 μl of 1011 exosome particles/mL weekly from week 5 to 8 post-surgery | Murine, medial meniscus, and medial collateral ligament transection | 12 weeks | Not undertaken | Histology: Less joint wear and cartilage matrix loss in the treated group undertaken. Improved Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) score | Immunostaining: greater type II collagen (Col II), aggrecan, and type I collagen expression |

| Wang et al. (2017) | Intra-articular injection of 5 μl of exosomes into Knee joint at week 4 and every 3 days thereafter | Murine, destabilization of medial meniscus (DMM) | 8 weeks | Not undertaken | Improved OARSI score in treated group. Reduced microscopic appearance of OA in treated group | Greater Col II staining and weaker ADAMTS5 staining in the treated group |

| Wu et al. (2019) | Intra-articular injection of 10 μl of exosome (1010 particles/ml) weekly or biweekly | Murine, DMM | 8 weeks | Improved gait; increased weight bearing on OA knee, swing speed and intensity in treated groups | Improved OARSI score in the treated group | Immunohistology showed increased Col II expression, decreased ADAMTS5 and MMP13 expression. |

| Zhang et al. (2016) | Intra-articular injection of 100 μg of exosomes weekly from surgery | Murine, surgically induced osteochondral defects on trochlear grooves of distal femur | 12 weeks | Macroscopic: Moderate improvement at 6 weeks, near-complete neotissue coverage and integration with surrounding cartilage at 12 weeks in treated groups. Improved International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) score at 12 vs. 6 weeks | Histology: smooth cartilage in five out of six treated defects at 12 weeks | Immunohistochemistry: intense GAG staining (>80%), high level of T2Col and low level of T1Col in treated lesions. Lubricin +ve cells found in superficial and middle zones of neo-cartilage |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Intra-articular injection of 100 μg of exosomes weekly from surgery | Murine, Surgically induced osteochondral defects on trochlear grooves of distal femur | 12 Weeks | Improved Wakitani macroscopic score at 2, 6, and 12 weeks compared to controls | More neotissue formation compared to control | Increased GAG and T2Col staining in treated groups. Increased Proliferative Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and decreased Cleaved Caspase-3 (CCP3) at 12 weeks in treated groups |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | Intra-articular injection of 100 μg of exosomes at weekly intervals starting from 2 weeks following OA induction | Murine, monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) induced cartilage loss in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) by inject of Monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) into upper compartment of the joint bilaterally | 12 weeks | Reduced Pain behavior in exosome treated rats from 2 weeks onwards as indicated by higher Head Withdrawal Threshold (HWT) as stimulated by Von Frey fibers | Micro-CT: Improved condylar height, cartilage thickness, matrix deposition and subchondral bone integrity from 8 weeks post treatment Histology: Improved Mankin score in treated groups at 4 weeks onwards |

Immunohistochemistry: Increased GAG and T2Col staining in treated groups. Increased Proliferative Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and decreased Cleaved Caspase-3 (CCP3) at 12 weeks in treated groups. PCR: reduced expression of IL-1B, BAX, alpha-SMA) and Substance P, Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), Tyrosine receptor Kinase A (TrkA). Increased TIMP2 expression. Decreased ADAMTS5 expression |

| Zhu X. et al. (2017) | Intra-articular injection with 8 μl (1010/ml) of exosomes on day 7,14, and 21 following OA induction | Murine, CIOA | 4 weeks | Improved ICRS score in both iMSC and sMSC group compared with OA group at endpoint | Improved OARSI score in all groups compared to untreated control. iMSC showed a greater improvement in OARSI score than sMSC | Greater Col II staining in treated groups. Greater Col II staining in iMSC compared to sMSC groups |

| Jin et al. (2020) | Intra-articular injection of 250 ng of exosomes in 5 μl | Murine, anterior crucial ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, medial cruciate ligament, lateral cruciate ligament, medial and lateral meniscus transection | 8 weeks | Not undertaken | Improved microscopic appearance, greater synovial cell infiltration and fibrous tissue formation in treated groups | Reduced MMP-3 and MMP-13 expression in treated group. Reduced synovial cell apoptosis in treated group. Decreased IL-1B in treated groups. Downregulation of PTGS2 |

In vivo Findings

Two studies measured pain scores and one conducted gait analysis following treatment with EVs, and all three showed improved functional scores. Zhang et al. (2019) used Micro-Computed Tomography (micro-CT) to assess cartilage morphology and found improved bone integrity from 8 weeks onwards. Gene-expression analysis undertaken in several studies. Mao et al. reported increased chondrogenic gene regulation after EV treatment. Using PCR, Zhang et al. (2019) and Jin et al. detected reduced regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in their studies.

Joint appearance was interrogated macroscopically, microscopically or using both approaches. All studies reported a reduction in cartilage loss after treatment with EVs. Microscopic histological analysis focused on assessing cartilage thickness and cartilage matrix appearance. Four studies conducted subjective quantification of appearance using the OARSI score. All studies found improved cartilage appearance or OARSI score in the treated groups, although Khatab et al. reported no treatment effect on subchondral bone volume at 3 weeks. Immunohistology was utilized in all studies and all reported increased collagen type II staining with several groups reporting reduced MMP3 immunostaining. Three studies reported reduced staining of apoptotic markers.

Quality of Studies

The SYRCLE tool was used to grade each study using 15 different parameters. Seven out of the 10 studies had a low level of concern overall and three studies had some concern toward risk of bias (Table 4). Blinding and detection bias constituted the main contributors to bias in the studies. There was little selection and reporting bias among the studies, but randomization of subjects were not mentioned in most studies. Overall, the studies included in this review were of high quality and low risk of bias.

Table 4.

Summary of risk of bias analysis.

| References | Selection bias in sequence generation | Selection bias in baseline characteristics | Selection bias in allocation concealment | Performance bias in random housing | Performance bias in blinding | Detected bias in random outcome assessment | Detected bias in blinding | Attrition bias in incomplete outcome data | Reportingbias | Number of Subjects (n =) | Number of Controls (n =) | Selectionbias | Performancebias | Detectionbias | Attritionbias | Reportingbias | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khatab et al. (2018) | Mice | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 11 | 11 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Mao et al. (2018) | Mice | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | yes | No | No | 10 | 10 | No | Unclear | yes | No | No | Some concerns |

| Tao et al. (2017) | rat | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 10 | 10 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wang et al. (2017) | Mice | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 20 | 12 | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Wu et al. (2019) | Mice | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | yes | No | No | 8 | 8 | No | Unclear | yes | No | No | Some concerns |

| Zhang et al. (2016) | rat | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 12 | 12 | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | rat | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 36 | 36 | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | rat | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | yes | No | No | 32 | 14 | No | Unclear | yes | No | No | Some concerns |

| Zhu X. et al. (2017) | Mice | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 10 | 5 | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Jin et al. (2020) | Mice | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | 10 | 10 | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

Discussion

All 10 studies in this review reported reduced cartilage loss following treatment with MSC-EVs. A variety of outcome measures were employed in each study to examine the impact of EVs on cartilage loss, but not all studies found improvements in every parameter measured. A total of 159 subjects were treated with MSC-EVs without significant or immunogenic complications. While all the MSC-EVs were derived from human MSCs, the subjects were all animal models of cartilage injury, and therefore only indirectly inform safety and effectiveness in human subjects.

The capacity for MSCs to expand ex vivo varies with cell source (Fazzina et al., 2016) and anatomical site (Davies et al., 2017). The ability of MSCs to undergo chondrogenic differentiation also appears to differ between cell source (Bernardo et al., 2007). The source of EVs varied significantly between studies as the MSCs were harvested from different tissues and anatomical donor sites. The influence of MSC source on the chondrogenic potential of EVs remains unclear, with some studies suggesting that certain MSC-EVs reduce type I and III collagen production (Li et al., 2013). There is evidence that the biological properties of EVs are dependent on MSC source (Kehl et al., 2019) and it is also apparent that certain MSCs, for example those derived from amniotic fluid, may produce a greater number of EVs than bone marrow-derived MSCs when controlled for cell number (Tracy et al., 2019). In this review, two studies used MSCs from immortalized cell lines (Zhang et al., 2018, 2019) this provides an advantage over autologous harvest as it is not invasive. Zhu et al. compared iPS-derived MSC-EVs with sMSC-derived EVs and found the former to be superior in cartilage repair. Relative cost and convenience of production will dictate which of these is favorable. These are important considerations in tissue engineering as the optimal source cell should achieve a balance between ease of harvest and acceptable EV production. MSC-EV bioactivity also appear to depend on cell-culture conditions, for example, the anti-apoptotic effects of adipose-derived MSC secretome can be affected by oxygen tension (An et al., 2015). Therefore, future studies will be required to delineate the relationship between MSC cell source and secretome in order to select the best source for optimal large-scale EV production.

Most studies in the literature examining EV function, in line with our findings, use ultracentrifugation as the main component of the isolation procedure (Gardiner et al., 2016). There is evidence that suggests that ultracentrifugation could increase the amount of contamination by macromolecules within the MSC culture media (Webber and Clayton, 2013). This may be of relevance in our interpretation as MSC-conditioned media is known to contain non-vesicular bioactive components that may promote chondrogenesis (Chen et al., 2018) and lead to an overestimation of EV effectiveness in cartilage repair. While this may make comparisons difficult, the augmented repair is not necessarily an undesired effect. Furthermore, while the effect of multiple washing stages that form part of the centrifugation process improves purity, it may decrease the total number of EVs obtained (Webber and Clayton, 2013) TFF was the next most commonly used method of concentrating EVs. Compared to ultracentrifugation, TFF achieves a greater EV yield, with a reduced amount of non-vesicular macromolecules contamination (Busatto et al., 2018). Other forms of flow-based purification such as Cross-flow isolation are also favorable over ultracentrifugation in terms of rate of production at large scale (McNamara et al., 2018). Ultimately, robust cost-effectiveness studies may be required to determine the optimal method of purification. The transferability of this review may also be limited by the inconsistent methodologies used by the studies to characterize the EVs used. Apart from one study that did not report on any EV markers (Khatab et al., 2018), all other studies identified markers recognized by the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) criteria (Théry et al., 2018). EV dimensions were found to range from 30 to 200 nm. The range of 50–150 nm was most commonly reported and may reflect the bias of measurement devices. Future studies should attempt to ascertain the main peak value within the detected range as Wu et al. (2019) did in their study.

Whilst all studies directly injected EVs intra-articularly, the dose delivered was highly varied. Although EV transplantation is yet to be tested in clinical studies, proof-of-concept human clinical trials of intra-articular injection of MSCs to treat cartilage lesions demonstrate a dose-dependent effect without increased risk of adverse effects (Jo et al., 2014). Similar studies will be required to establish such a relationship for EV transplantation. In MSC treatment of cartilage lesions, intra-articular injection appear to promote good engraftment rates with minimal off-site engraftment (Satué et al., 2019). In in vivo studies of anterior cruciate ligament repair, intravenous injection of MSCs concomitantly with intra-articular injection produced improved outcomes (Muir et al., 2016). Likewise, intravenous EV injection appear to produce a dose-dependent immunosuppressive effect that may be beneficial for treating arthritis (Cosenza et al., 2018), but the effect on cartilage repair remains unknown, and the potential for off-site engraftment of EVs is not yet characterized.

All animal studies to date on human-derived MSC-EVs have focussed on murine models. Articular cartilage repair can be studied in murine models in several ways. Firstly, the joint may be surgically destabilized such as in destabilization of medial meniscus (DMM) models, leading to altered weight-bearing and subsequently generalized OA changes, which includes cartilage loss. These models are reliable, reproducible, and have high disease penetrance. The time-course over which cartilage changes develop is delayed and therefore recapitulates the nature of human disease (Glasson et al., 2007). Cartilage can also be excised surgically through induction of an osteochondral defect. These defects may progress at different rates depending on the operative site (Haase et al., 2019), and so makes for difficulty in determining the optimal timing of EV treatment. In contrast, DMM models may progress to display cartilage loss at time points later than direct osteochondral injury and therefore may not benefit from EV treatment in the acute post-injury phase. The amount of lesion healing however appeared to be similar when comparing findings from Zhang et al. (2016) and Zhang et al. (2018), where the same treatment was given after DMM and direct osteochondral injury, respectively. Cartilage loss may also be induced using enzymes or chemicals that degrade the cartilage. Three studies induced chondral injury in murine models using collagenase and one study used monosodium iodoacetate (MIA). Chemical induction is less predictable and may also attenuate the effects of cell-based therapies mimicking its effects on tissue-native cells (Taghizadeh et al., 2018). One study focused on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). As the pathoaetiology and epidemiology of these non-weight bearing joints typically differ, with radiographic TMJ cartilage loss often being asymptomatic (Schmitter et al., 2010), it may not be relevant to compare functional outcomes following treatment.

It is important to determine standardized methods of assessing outcomes relevant to cartilage repair. Several studies reported improvements in the macroscopic appearance of cartilage; while macroscopic appearance scoring is predictive of histological scoring (Goebel et al., 2017), it is unclear how this correlates with functional improvements. The three studies that used collagenase to induce cartilage loss, often termed collagenase induced OA (CIOA) models, assessed the highly clinically relevant outcomes of pain behavior, with both reporting reduction from early stages. It is difficult to draw conclusions from these results as cartilage loss and eventual OA in the murine model is typically late in onset and appears over 10 weeks following injury (Inglis et al., 2008). It is encouraging however, that all studies reported improved microscopic cartilage repair, with several studies employing various subjective quantitative scoring systems (Tao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Zhu Y. et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019). It may be informative to conduct a pooled analysis of such outcomes, but it is unlikely to be meaningful in this study owing to the heterogeneity in scores used. Not all studies reported favorable outcomes when assessing markers of cartilage repair. Khatab et al. conducted an immunohistochemical analysis of iNOS and CD206 expression which are markers of inflammation and M2 macrophage, respectively (Fahy et al., 2014), and found no difference between the groups at the end of the study. Inflammation probably attenuates cartilage repair by interfering with chondrocyte activity and so could be of greater relevance in the acute stage (Tung et al., 2002). The majority of studies showed improved collagen immunostaining, and greater expression of chondrogenic genes in tissue samples. Several groups evaluated cell apoptosis as an outcome and found decreased expression of markers of apoptosis following treatment (Zhang et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2020). Indeed, chondrocyte apoptosis may be reflective of matrix depletion in the cartilage (Kim et al., 2001).

In addition to promoting chondrogenesis in chondrocytes, it is likely that EVs contribute to cartilage repair via effects on other cell types. Macrophages are postulated to be a key target for MSC-EVs, with evidence suggesting that EVs cause an M2 phenotype polarization that promotes resolution of inflammation and so promotes cartilage repair (Chen et al., 2019). This notion is supported by the fact that macrophages pre-conditioned with MSC-EVs, termed EV-educated macrophages (EEMs) support tendon healing in vivo to a greater extent than treatment with MSC-EVs alone (Chamberlain et al., 2019). Others suggest that MSC-EV secretome actually augments the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs via autocrine action. It appears that IL-1β-pretreated MSCs induce macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype only when in the presence of EVs containing miR-146a (Song et al., 2017). Transplantation of circulating EVs from septic mice however, appear to encourage neutrophil migration and macrophage inflammation; this is attributed to certain miRNAs including miR-126-3p, miR-222-3p, and miR-181a-5p, suggesting that EV-dependent modulation of inflammation is content and context dependent (Xu et al., 2018). Further to this, caution should be exercised with MSC-EV transplantation in certain patient cohorts, as MSC-EV have been shown to attenuate the ability of macrophages to suppress cancer cells, and in doing so promotes tumorigenicity (Ren et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Due to the plethora of pathways through which MSC-EVs can promote cartilage repair, a key step to studying their effects in animal models is to establish the roles of the different bioactive components within EVs. Similarly, outcome measures utilized in studies should complement this. We recommend that cartilage appearance and chondrogenic gene expression should be primary outcomes in addition to quantifiable and clinically relevant functional outcomes such as pain reduction or animal gait analysis. Likewise, it would be beneficial to establish a link between functional and histological outcomes, as the value of assessing histology may otherwise be minimal. In order to establish the optimal way to deliver clinical benefit using MSC-EVs, the most efficient MSC cell source, methodology of cell culture and EV purification should be investigated for the purposes of cartilage repair. Finally, randomized studies in animal models that recapitulates the human disease will be necessary in order to establish a dose-response relationship and therefore clinical safety before we proceed to human trials.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

KT and WK conceptualized the review manuscript. KT wrote the manuscript under the supervision of FH and WK. KT and AK assembled study data and conducted literature searches. KR and CM conducted data analysis and risk of bias analysis. All authors contributed to editing and approving the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Versus Arthritis (Formerly Arthritis Research UK) through Versus Arthritis Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Therapies Center (Grant 21156).

References

- An H. Y., Shin H. S., Choi J. S., Kim H. J., Lim J. Y., Kim Y. M. (2015). Adipose mesenchymal stem cell secretome modulated in hypoxia for remodeling of radiation-induced salivary gland damage. PLoS ONE 10:e0141862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckermann B. M., Kallifatidis G., Groth A., Frommhold D., Apel A., Mattern J., et al. (2008). VEGF expression by mesenchymal stem cells contributes to angiogenesis in pancreatic carcinoma. Br. Cancer J. 99, 622–631. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo M. E., Emons J. A. M., Karperien M., Nauta A. J., Willemze R., Roelofs H., et al. (2007). Human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow display a better chondrogenic differentiation compared with other sources. Connect. Tissue Res. 48, 132–140. 10.1080/03008200701228464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berstock J. R., Beswick A. D., Lenguerrand E., Whitehouse M. R., Blom A. W. (2014). Mortality after total hip replacement surgery: a systematic review. Bone Joint Res. 3, 175–182. 10.1302/2046-3758.36.2000239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bexkens R., Ogink P. T., Doornberg J. N., Kerkhoffs G. M. M. J., Eygendaal D., Oh L. S., et al. (2017). Donor-site morbidity after osteochondral autologous transplantation for osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 25, 2237–2246. 10.1007/s00167-017-4516-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borakati A., Mafi R., Mafi P., Khan W. S. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for cartilage repair. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 13, 215–225. 10.2174/1574888X12666170915120620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busatto S., Vilanilam G., Ticer T., Lin W.-L., Dickson D., Shapiro S., et al. (2018). Tangential flow filtration for highly efficient concentration of extracellular vesicles from large volumes of fluid. Cells 7:273. 10.3390/cells7120273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J. M., Shin E. K., Sung J. H., Moon G. J., Kim E. H., Cho Y. H., et al. (2018). Efficient scalable production of therapeutic microvesicles derived from human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 8:1171. 10.1038/s41598-018-19211-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain C. S., Clements A. E. B., Kink J. A., Choi U., Baer G. S., Halanski M. A., et al. (2019). Extracellular vesicle-educated macrophages promote early achilles tendon healing. Stem Cells 37, 652–662. 10.1002/stem.2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Zheng L., Wang Y., Tao M., Xie Z., Xia C., et al. (2019). Desktop-stereolithography 3D printing of a radially oriented extracellular matrix/mesenchymal stem cell exosome bioink for osteochondral defect regeneration. Theranostics 9, 2439–2459. 10.7150/thno.31017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C., Chang Y. W., Tan K. P., Shen Y. S., Wang Y. H., Chang C. H. (2018). Can mesenchymal stem cells and their conditioned medium assist inflammatory chondrocytes recovery? PLoS ONE 13:e0205563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho P. S., Messina D. J., Hirsh E. L., Chi N., Goldman S. N., Lo D. P., et al. (2008). Immunogenicity of umbilical cord tissue-derived cells. Blood 111, 430–438. 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza S., Toupet K., Maumus M., Luz-Crawford P., Blanc-Brude O., Jorgensen C., et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes are more immunosuppressive than microparticles in inflammatory arthritis. Theranostics 8, 1399–1410. 10.7150/thno.21072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B. M., Snelling S. J. B., Quek L., Hakimi O., Ye H., Carr A., et al. (2017). Identifying the optimum source of mesenchymal stem cells for use in knee surgery. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 1868–1875. 10.1002/jor.23501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies-Tuck M. L., Wluka A. E., Wang Y., Teichtahl A. J., Jones G., Ding C., et al. (2008). The natural history of cartilage defects in people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16, 337–342. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Vizio D., Morello M., Dudley A. C., Schow P. W., Adam R. M., Morley S., et al. (2012). Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 1573–1584. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre H., Ducret M., Degoul O., Rodriguez J., Perrier-Groult E., Aubert-Foucher E., et al. (2019). Characterization of different sources of human MSCs expanded in serum-free conditions with quantification of chondrogenic induction in 3D. Stem Cells Int. 2019:2186728. 10.1155/2019/2186728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy N., de Vries-van Melle M. L., Lehmann J., Wei W., Grotenhuis N., Farrell E., et al. (2014). Human osteoarthritic synovium impacts chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via macrophage polarisation state. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 1167–1175. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima F., Ekstrom K., Nazarenko I., Maugeri M., Valadi H., Hill A. F., et al. (2017). Non-coding RNAs in mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: deciphering regulatory roles in stem cell potency, inflammatory resolve, and tissue regeneration. Front. Genet. 8:161. 10.3389/fgene.2017.00161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzina R., Iudicone P., Fioravanti D., Bonanno G., Totta P., Zizzari I. G., et al. (2016). Potency testing of mesenchymal stromal cell growth expanded in human platelet lysate from different human tissues. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 7:122. 10.1186/s13287-016-0383-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes T. L., Kimura H. A., Pinheiro C. C. G., Shimomura K., Nakamura N., Ferreira J. R., et al. (2018). Human synovial mesenchymal stem cells good manufacturing practices for articular cartilage regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 24, 709–716. 10.1089/ten.tec.2018.0219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag J., Bates D., Wickham J., Shah K., Huguenin L., Tenen A., et al. (2019). Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Regen. Med. 14, 213–230. 10.2217/rme-2018-0161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C., Di Vizio D., Sahoo S., Théry C., Witwer K. W., Wauben M., et al. (2016). Techniques used for the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles: results of a worldwide survey. J. Extracell. Vesicles 5:32945. 10.3402/jev.v5.32945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam M. H., Lie S. A., Salter A., Furnes O., Graves S. E., Havelin L. I., et al. (2013). The progression of end-stage osteoarthritis: analysis of data from the Australian and Norwegian joint replacement registries using a multi-state model. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 21, 405–412. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasson S. S., Blanchet T. J., Morris E. A. (2007). The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 1061–1069. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel L., Orth P., Cucchiarini M., Pape D., Madry H. (2017). Macroscopic cartilage repair scoring of defect fill, integration and total points correlate with corresponding items in histological scoring systems – a study in adult sheep. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25, 581–588. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L.-H., Zhang T.-T., Li Y., Yan H.-J., Qi H., Li F.-R. (2015). Immunogenicity of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells transplanted via different routes in diabetic rats. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 12, 444–455. 10.1038/cmi.2014.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase T., Sunkara V., Kohl B., Meier C., Bußmann P., Becker J., et al. (2019). Discerning the spatio-temporal disease patterns of surgically induced OA mouse models. PLoS ONE 14:e0213734. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooijmans C. R., Rovers M. M., De Vries R. B. M., Leenaars M., Ritskes-Hoitinga M., Langendam M. W. (2014). SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14:43. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Quinn D., Sadovsky Y., Suresh S., Hsia K. J. (2017). Formation and size distribution of self-assembled vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 2910–2915. 10.1073/pnas.1702065114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis J. J., McNamee K. E., Chia S. L., Essex D., Feldmann M., Williams R. O., et al. (2008). Regulation of pain sensitivity in experimental osteoarthritis by the endogenous peripheral opioid system. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 3110–3119. 10.1002/art.23870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Ren J., Qi S. (2020). Human bone mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes overexpressing microRNA-26a-5p alleviate osteoarthritis via down-regulation of PTGS2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 78:105946. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo C. H., Lee Y. G., Shin W. H., Kim H., Chai J. W., Jeong E. C., et al. (2014). Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells 32, 1254–1266. 10.1002/stem.1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnoub A. E., Dash A. B., Vo A. P., Sullivan A., Brooks M. W., Bell G. W., et al. (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 449, 557–563. 10.1038/nature06188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri W., Watanabe J., Toyama N., Osugi M., Sakaguchi K., Hibi H. (2017). Clinical study of bone regeneration by conditioned medium from mesenchymal stem cells after maxillary sinus floor elevation. Implant Dent. 26, 607–612. 10.1097/ID.0000000000000618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl D., Generali M., Mallone A., Heller M., Uldry A.-C., Cheng P., et al. (2019). Proteomic analysis of human mesenchymal stromal cell secretomes: a systematic comparison of the angiogenic potential. NPJ Regen. Med. 4, 1–13. 10.1038/s41536-019-0070-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatab S., van Osch G. J. V. M., Kops N., Bastiaansen-Jenniskens Y. M., Bos P. K., Verhaar J. A. N., et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stem cell secretome reduces pain and prevents carti lage damage in a muri ne osteoarthri ti s model. Eur. Cells Mater. 36, 218–230. 10.22203/eCM.v036a16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. A., Suh D. I., Song Y. W. (2001). Relationship between chondrocyte apoptosis and matrix depletion in human articular cartilage. J. Rheumatol. 28, 2038–2045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Steinberg D. R., Burdick J. A., Mauck R. L. (2019). Extracellular vesicles mediate improved functional outcomes in engineered cartilage produced from MSC/chondrocyte cocultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 1569–1578. 10.1073/pnas.1815447116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Yan Y., Wang B., Qian H., Zhang X., Shen L., et al. (2013). Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 845–854. 10.1089/scd.2012.0395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linero I., Chaparro O. (2014). Paracrine effect of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue in bone regeneration. PLoS ONE 9:e107001. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao G., Zhang Z., Hu S., Zhang Z., Chang Z., Huang Z., et al. (2018). Exosomes derived from miR-92a-3poverexpressing human mesenchymal stem cells enhance chondrogenesis and suppress cartilage degradation via targeting WNT5A. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9:247. 10.1186/s13287-018-1004-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masgutov R., Masgutova G., Mullakhmetova A., Zhuravleva M., Shulman A., Rogozhin A., et al. (2019). Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells applied in fibrin glue stimulate peripheral nerve regeneration. Front. Med. 6:68. 10.3389/fmed.2019.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcalindon T. E., Bannuru R. R., Sullivan M. C., Arden N. K., Berenbaum F., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M., et al. (2014). OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 363–388. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R. P., Caro-Vegas C. P., Costantini L. M., Landis J. T., Griffith J. D., Damania B. A., et al. (2018). Large-scale, cross-flow based isolation of highly pure and endocytosis-competent extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7:1541396. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1541396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir P., Hans E. C., Racette M., Volstad N., Sample S. J., Heaton C., et al. (2016). Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells modulate molecular markers of inflammation in dogs with cruciate ligament rupture. PLoS ONE 11:e0159095. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz M., Shah N., Zanetti B., Maugeri M., Silvestre R., Fatima F., et al. (2018). Extracellular vesicles and matrix remodeling enzymes: the emerging roles in extracellular matrix remodeling, progression of diseases and tissue repair. Cells 7:167. 10.3390/cells7100167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoro T., Takagaki Y., Okura H., Matsuyama A. (2018). Trends in clinical trials for articular cartilage repair by cell therapy. NPJ Regen. Med. 3:17. 10.1038/s41536-018-0055-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsdotter A. K., Petersson I. F., Roos E. M., Lohmander L. S. (2003). Predictors of patient relevant outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a prospective study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62, 923–930. 10.1136/ard.62.10.923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S., Pedowitz D. I., Parekh S. G., Sennett B. J., Okereke E. (2007). The morbidity associated with osteochondral harvest from asymptomatic knees for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am. J. Sports Med. 35, 80–85. 10.1177/0363546506290986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis M., Mavin E., Nicholson L., Green K., Dickinson A. M., Wang X. (2018). Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate dendritic cell maturation and function. Front. Immunol. 9:2538. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W., Hou J., Yang C., Wang H., Wu S., Wu Y., et al. (2019). Extracellular vesicles secreted by hypoxia pre-challenged mesenchymal stem cells promote non-small cell lung cancer cell growth and mobility as well as macrophage M2 polarization via miR-21-5p delivery. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38:62. 10.1186/s13046-019-1027-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A. F., Lázaro-Ibáñez E., Forsgard M. A. M., Shatnyeva O., Osteikoetxea X., Karlsson F., et al. (2019). Extracellular vesicles induce minimal hepatotoxicity and immunogenicity. Nanoscale 11, 6990–7001. 10.1039/C8NR08720B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satué M., Schüler C., Ginner N., Erben R. G. (2019). Intra-articularly injected mesenchymal stem cells promote cartilage regeneration, but do not permanently engraft in distant organs. Sci. Rep. 9:10153. 10.1038/s41598-019-46554-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter M., Essig M., Seneadza V., Balke Z., Schröder J., Rammelsberg P. (2010). Prevalence of clinical and radiographic signs of osteoarthrosis of the temporomandibular joint in an older persons community. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 39, 231–234. 10.1259/dmfr/16270943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Dou H., Li X., Zhao X., Li Y., Liu D., et al. (2017). Exosomal miR-146a contributes to the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of interleukin-1β-primed mesenchymal stem cells against sepsis. Stem Cells 35, 1208–1221. 10.1002/stem.2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh R. R., Cetrulo K. J., Cetrulo C. L. (2018). Collagenase impacts the quantity and quality of native mesenchymal stem/stromal cells derived during processing of umbilical cord tissue. Cell Transplant. 27, 181–193. 10.1177/0963689717744787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao S.-C., Yuan T., Zhang Y.-L., Yin W.-J., Guo S.-C., Zhang C.-Q. (2017). Exosomes derived from miR-140-5p-overexpressing human synovial mesenchymal stem cells enhance cartilage tissue regeneration and prevent osteoarthritis of the knee in a rat model. Theranostics 7, 180–195. 10.7150/thno.17133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C., Witwer K. W., Aikawa E., Alcaraz M. J., Anderson J. D., Andriantsitohaina R., et al. (2018). Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7:1535750. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy S. A., Ahmed A., Tigges J. C., Ericsson M., Pal A. K., Zurakowski D., et al. (2019). A comparison of clinically relevant sources of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: bone marrow and amniotic fluid. J. Pediatr. Surg. 54, 86–90. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung J. T., Arnold C. E., Alexander L. H., Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V., Venta P. J., Richardson D. W., et al. (2002). Evaluation of the influence of prostaglandin E2 on recombinant equine interleukin-1 β-stimulated matrix metalloproteinases 1, 3, and 13 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 expression in equine chondrocyte cultures. Am. J. Vet. Res. 63, 987–993. 10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiewicz A., Petersson I. F., Björk J., Hawker G., Dahlberg L. E., Lohmander L. S., et al. (2014). Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: a population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 1826–1832. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buul G. M., Villafuertes E., Bos P. K., Waarsing J. H., Kops N., Narcisi R., et al. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells secrete factors that inhibit inflammatory processes in short-term osteoarthritic synovium and cartilage explant culture. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 20, 1186–1196. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindas Bolaños R. A., Cokelaere S. M., Estrada McDermott J. M., Benders K. E. M., Gbureck U., Plomp S. G. M., et al. (2017). The use of a cartilage decellularized matrix scaffold for the repair of osteochondral defects: the importance of long-term studies in a large animal model. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25, 413–420. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassov A. V., Magdaleno S., Setterquist R., Conrad R. (2012). Exosomes: current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochimica Biophys. Acta 1820, 940–948. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk L. A., van Dooremalen S. F. J., Liv N., Klumperman J., Coffer P. J., Saris D. B. F., et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote human cartilage regeneration in vitro. Theranostics 8, 906–920. 10.7150/thno.20746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yu D., Liu Z., Zhou F., Dai J., Wu B., et al. (2017). Exosomes from embryonic mesenchymal stem cells alleviate osteoarthritis through balancing synthesis and degradation of cartilage extracellular matrix. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8:189. 10.1186/s13287-017-0632-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber J., Clayton A. (2013). How pure are your vesicles? J. Extracell. Vesicles 2:19861. 10.3402/jev.v2i0.19861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A. E., Locker P. H., Mayer E. N., Cvetanovich G. L., Tilton A. K., Erickson B. J., et al. (2018). Clinical outcomes after microfracture of the knee: midterm follow-up. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 6:2325967117753572. 10.1177/2325967117753572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer K. W., Van Balkom B. W. M., Bruno S., Choo A., Dominici M., Gimona M., et al. (2019). Defining mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived small extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 8:1609206. 10.1080/20013078.2019.1609206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf A. D., Pfleger B. (2003). Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull. World Health Organ. 81, 646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Kuang L., Chen C., Yang J., Zeng W. N., Li T., et al. (2019). miR-100-5p-abundant exosomes derived from infrapatellar fat pad MSCs protect articular cartilage and ameliorate gait abnormalities via inhibition of mTOR in osteoarthritis. Biomaterials 206, 87–100. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Feng Y., Jeyaram A., Jay S. M., Zou L., Chao W. (2018). Circulating plasma extracellular vesicles from septic mice induce inflammation via MicroRNA- and TLR7-dependent mechanisms. J. Immunol. 201, 3392–3400. 10.4049/jimmunol.1801008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Wu Y., Xiong Z., Zhou Y., Ye Z., Tan W. S. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cells reshape and provoke proliferation of articular chondrocytes by paracrine secretion. Sci. Rep. 6:32705. 10.1038/srep32705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Chu W. C., Lai R. C., Lim S. K., Hui J. H. P., Toh W. S. (2016). Exosomes derived from human embryonic mesenchymal stem cells promote osteochondral regeneration. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24, 2135–2140. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Chuah S. J., Lai R. C., Hui J. H. P., Lim S. K., Toh W. S. (2018). MSC exosomes mediate cartilage repair by enhancing proliferation, attenuating apoptosis and modulating immune reactivity. Biomaterials 156, 16–27. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Teo K. Y. W., Chuah S. J., Lai R. C., Lim S. K., Toh W. S. (2019). MSC exosomes alleviate temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis by attenuating inflammation and restoring matrix homeostasis. Biomaterials 200, 35–47. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Badawi M., Pomeroy S., Sutaria D. S., Xie Z., Baek A., et al. (2017). Comprehensive toxicity and immunogenicity studies reveal minimal effects in mice following sustained dosing of extracellular vesicles derived from HEK293T cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 6:1324730. 10.1080/20013078.2017.1324730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Wang Y., Zhao B., Niu X., Hu B., Li Q., et al. (2017). Comparison of exosomes secreted by induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells and synovial membrane-derived mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8:64. 10.1186/s13287-017-0510-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwolanek D., Satué M., Proell V., Godoy J. R., Odörfer K. I., Flicker M., et al. (2017). Tracking mesenchymal stem cell contributions to regeneration in an immunocompetent cartilage regeneration model. JCI Insight 2:e87322. 10.1172/jci.insight.87322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.