Abstract

We propose a simple model for chromatin organization based on the interaction of the chromatin fibers with lamin proteins along the nuclear membrane. Lamin proteins are known to be a major factor that influences chromatin organization and hence gene expression in the cells. We provide a quantitative understanding of lamin-associated chromatin organization in a crowded macromolecular environment by systematically varying the heteropolymer segment distribution and the strength of the lamin-chromatin attractive interaction. Our minimal polymer model reproduces the formation of lamin-associated-domains and provides an in silico tool for quantifying domain length distributions for different distributions of heteropolymer segments. We show that a Gaussian distribution of heteropolymer segments, coupled with strong lamin-chromatin interactions, can qualitatively reproduce observed length distributions of lamin-associated-domains. Further, lamin-mediated interaction can enhance the formation of chromosome territories as well as the organization of chromatin into tightly packed heterochromatin and the loosely packed gene-rich euchromatin regions.

Significance

The physical principles that underlie the organization of interphase chromosomes inside the nucleus remain an important open question in biology, and lamin proteins that are mostly found along the inner surface of the nucleus play an important role in chromosome organization. We show how sequence heterogeneity of chromatin, coupled with a strong lamin-chromatin interaction, translates to a specific pattern of lamin-binding domains that mimics the experimental observations. Our work shows the importance of these lamin-chromatin interactions in understanding the large-scale genome organization.

Introduction

The link between microscopic and macroscopic descriptions of genome structure and function is one of the key questions of present-day biology (1, 2, 3). In particular, the structure and folding principles of the interphase chromosomes have been the subject of much debate over the last decade (4, 5, 6). Although the structure of DNA double helix and histone proteins that form the nucleosome is well understood (7, 8, 9), how the nucleosomes finally organize to form the interphase chromosomes still remains an open question (10, 11, 12). The organization of the chromatin determines the function of the cell type, with the epigenetic state of a differentiated cell correlated with differential packaging of the chromosome. Understanding the principle behind the chromatin organization thus has important implications for the proper functioning of the cell as misfolding errors lead to several human pathologies.

The advent of experimental techniques such as chromosome conformation capture (2C/3C/5C/Hi-C) (13, 14, 15, 16) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (17,18) has provided a wealth of information on the large-scale structure of the chromosome. A key experimental observation has been that different chromosomes segregate into different territories with minimal contact between them (19, 20, 21). Additionally, the chromatin can also be classified into transcriptionally silent heterochromatin and gene expression active euchromatin, with heterochromatin regions being more tightly packed and located preferentially in the nuclear periphery. The euchromatin, in contrast, is relatively loosely packed and located in the interior (22, 23, 24, 25).

One of the key mediators in the organization of the genome are interactions between the nuclear lamina (NL) and chromatin. The NL is a complex structure that acts as a scaffold for various proteins that regulate nuclear structure and function (26,27). Mammalian cells contain two B-type lamins, B1 and B2, and two A-type lamins, lamins A and C. In most cells, lamins B1 and B2 are concentrated along the NL in the nuclear periphery, whereas A-type lamins are also found in the nuclear interior (28,29). The lamin proteins in the NL play an important role in the organization of the chromosomes within the nucleus. Experimental studies have shown that certain regions of the chromosomes lie in close proximity to the lamina, and DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID) experiments have been used to build a map of chromosome lamin interactions (26,27,30,31). These experiments reveal that there are large domains of chromosomal regions that have a high degree of affinity for nuclear lamins (called lamina-associated-domains [LADs]), alternating with regions of very low affinity. The LADs in the human genome can be very large, ranging from 0.1 to 10 Mb in length (30,31). The LADs are associated with gene poor regions of the chromosome, with the mean gene density being around half of that in the non-LAD regions. Additionally, other gene activity markers, such as PolII and the histone mark H3K4me2 are also repressed within LADs, indicating that LADs represent a strongly repressive chromatin environment (26,27,30). A large fraction of the human chromosome (∼40%) consists of LADs (30).

Subsequent experiments have also shown that the interaction between LADs and lamin proteins are stochastic in nature, with only a fraction of the total LADs being in contact with the NL in a given cell (31). After the cell division process, a new subset of LADs can be in contact with the NL. Chromatin immunoprecipitation DamID experiments have shown that only those LADs that interact with the lamin proteins have enhanced levels of H3K9me2, which implies that this methylation mark status is also stochastic and directly correlated with the LAD position (31). These experiments conclusively show that LADs are positioned stochastically within the nucleus.

There has been a considerable body of theoretical work in understanding spatial organization of chromatin using polymer models (32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53). Two major classes of models have been studied so far: 1) the dynamic loop and associated models (34, 35, 36) and 2) binder switch and associated models (38, 39, 40). The dynamic loop model associates chromosome compaction via diffusional motion of polymer segments. Accounting for the excluded-volume interactions, they showed how repulsion between two looping chromosomes induce entropy-driven segregation of the chromosomes (34, 35, 36). In contrast, the binder-switch model assigns attractive interactions between transcription factors as the dominant mechanism of large-scale genome organization. A polymer with excluded-volume interactions among segments and attractive interactions between monomers and spherical particles mimics the chromatin and the transcription factors, respectively, in this model. A phase transition between an extended coil and compact phase was observed as a function of the fraction of attractive sites, the interaction strength, and concentration of mobile binders that may associate with the polymer (38,39). The formation of topologically associated domains seen in contact maps measured by Hi-C experiments can be explained using heteropolymer sequence (40). Further models allow for incorporation of epigenetic state-dependent interactions among compact polymer segments, which provide a way to explain multistability in epigenome folding (42).

An important missing ingredient in the proposed models has been the effect of the NL-chromatin interactions. Inspired by experiments, in this article, we propose a simple polymer model that incorporates confinement as well as the attractive interactions between the chromosomes and the lamin proteins. The main results are as follows: 1) for a homopolymer, we reproduce experimentally observed scaling of chromatin size as a function of basepairs and their associated contact probabilities; 2) for a heteropolymer with sequence control, we obtain length distributions of LADs; and 3) for a mixture of homo- and heteropolymers, we observe phase separation of chromosomes and formation of distinct territories. Our work provides a minimal phenomenological model, with a small number of coarse-grained parameters, aimed at quantifying observable genome organization through lamin-chromatin interactions.

Materials and Methods

We model the chromatin as a self-avoiding polymer chain of N beads, each of diameter b0, connected by harmonic springs. The polymer is confined within a sphere of radius R. The polymer consists of two types of beads, type A and type B (see Fig. 1). The inner surface of the sphere attracts beads of type A, mimicking lamin-chromatin interactions. The fraction of type A beads is denoted by f. The lamin interactions occur if a bead of type A lies within a cut-off distance Rc = b0 from the inner wall of the sphere. The energy of the polymer chain is thus given by the Hamiltonian

| (1) |

where the first term models the usual bead-spring interaction, the second term incorporates the self-avoidance constraint, and the third term models the lamin-chromatin interactions. The index tj denotes the type of bead (0 for A-type beads and 1 for B-type beads). The beads are chosen to have hard-core excluded volume, i.e., u → ∞. The lamin-chromatin binding energy is given by EB. Equilibrium conformations of this confined polymer system in the presence of an attractive boundary is then simulated following the Metropolis Monte Carlo (MC) scheme.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of a bead-spring polymer model with type-A and type-B beads confined within a sphere (see text). To see this figure in color, go online.

The radius R of the nucleus and the polymer volume fraction is chosen in our model to conform to a biologically relevant scenario. Human nuclei sizes can range between diameters of 6 and 11 μm (54,55), although the total number of basepairs in the human genome is of the order of 6 billion (6 × 109 bp) (54). Assuming that a 30-nm chromatin bead has 3000 bp (56,57), the chromatin volume fraction of the human nuclei ranges from 0.004 to ∼0.25. For our simulated confined polymer with N = 512 monomers, the radius of the confining sphere then corresponds to for a volume fraction of 0.004 and R = 7 for a volume fraction of 0.25. We look at physical quantities of interest for these two values of the radius R = 12 and R = 7 in this article. k = 30 kBT denotes the spring constant of the bead-spring polymer and is taken to be in the same range as previous studies (34,46).

The equilibrium conformations of this confined polymer system is simulated using the Metropolis MC scheme. A monomer is selected at random and given an infinitesimal displacement in a random direction. If the new configuration does not violate self-avoidance, it is accepted with a Boltzmann probability , where is the energy difference between the states, and β = 1/kBT, where T is the temperature of the system, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. We have ensured that the system is equilibrated by computing the total energy as a function of MC steps. The energy saturates after τeq ∼ N2 ∼ 105 MC steps. Statistical averages of quantities reported are calculated after τ = 10τeq for a duration of τMC = 109 steps. This ensures that the results are independent of the choice of initial conditions.

Results

Homopolymer

We first consider a homopolymer with all type-A beads that can bind to the lamin proteins, i.e., . This is done for both values of the nuclear radii used in our investigations, R = 7 and R = 12, for a range of binding energies .

As shown in Fig. 2 a, the mean-square displacement as a function of contour length of the polymer s scales as <R2(s)>∼s2ν, with an exponent ν between 0.4 and 0.7 for short genomic distances, saturates for higher values. The saturation of the mean-square separation is a simple consequence of the confinement of the polymer. For R = 12, ν ≈ 0.5–0.7, whereas for R = 7, ν ≈ 0.4–0.6, which corresponds extremely well with measured values from FISH data (58, 59, 60). We note that recent experiments have indicated smaller values of ν at higher spatial resolutions (61, 62, 63). Polymer models at finer scales of resolution may be needed to obtain smaller values of the exponent. Apart from lamin-mediated interactions, chromatin can also interact with various proteins in the bulk. These protein-mediated interactions can serve to decrease the ν value reported here.

Figure 2.

(a) Mean-square-distance as a function of the separation s for different binding energies and different volume fractions. (b) The contact probability (pc(s)) as a function of the separation s for different binding energies and different volume fractions. (c) The volume fraction within spherical shells as a function of the normalized radial distance is shown. (d) The (normalized) number of monomers within a spherical shell as a function of the normalized radial distance is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also compute the contact probability for two monomers separated by s basepairs to approach within a certain cut-off distance rcut of each other. Consistent with previous studies, we choose rcut = 2.5b0 (39). For small basepair separations, the contact probability decreases before tapering off at large values (see Fig. 2 b). The contact probability decreases following a power law of the form pc(s) = s−β for small values of s. The exponent β ≈ 1.5–1.6 for R = 12 and β ≈ 0.9–1.0 for R = 7, consistent with Hi-C experiments (64,65).

Further, we compute volume fraction of monomers as a function of the radial distance from the center, i.e., we count the number of monomers nr in a thin shell r → r + Δr, with Δr = 1, and compute the volume occupied by these nr monomers normalized by the volume of the shell. This is shown in Fig. 2 c. The corresponding number of monomers (normalized by the total number N) in each shell is shown in Fig. 2 d. Entropic confinement, in the absence of lamin-protein interactions (i.e., EB = 0), leads to a low volume fraction near the surface and a constant value throughout the rest of the nucleus. For EB ≥ 2 kBT, the chromatin volume fraction at the nuclear periphery increases such that the outermost shell is more densely packed than the inner ones. This is consistent with observations of tighter chromatin packing in heterochromatin regions (22, 23, 24, 25) and also correlates with the hypothesis that lamin-protein-chromatin interactions are more prominent in heterochromatin regions, which explains their tighter packing and consequently, higher volume fractions.

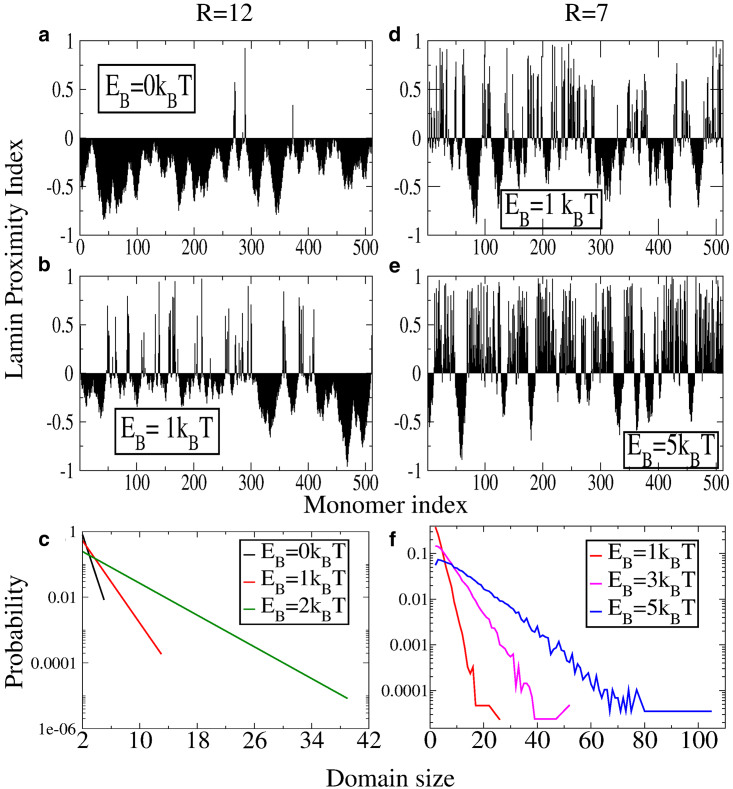

Next, we investigate domain formation within our model to compare against DamID experimental data. We define the lamin proximity index (LPI) for the ith monomer as, , which determines the position of the center of a monomer with respect to the distance Rc, beyond which it interacts with the lamin. The LPI value ranges from [−1:1], with positive values indicating bond formation with the lamin. Fig. 3, a, b, d, and e show the variation of LPI as a function of the binding energy EB for both spheres of radii R = 12 and R = 7, respectively.

Figure 3.

Lamin proximity indices for R = 12 and binding energies (a) EB = 0 kBT and (b) EB = 1 kBT. Shown are the proximity indices for R = 7 and binding energies (d) EB = 1 kBT and (e) EB = 5 kBT. (c) and (f) Shown are domain size distributions for different binding energies for R = 12 and R = 7, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

The lamin-associated chromatin domains for the homopolymer have a size distribution peaked around , with the characteristic length scale monotonically increasing as a function of the binding energy EB (Fig. 3, c and f). In contrast, the size distribution obtained from DamID data is peaked around a nonzero value of . This arises because of the fact that for chromatin, roughly 40% of the human genome can associate with the lamin (30). This necessitates a heteropolymer model of chromatin in which only a fraction f of the beads (type A) can associate with the lamin proteins.

Polymer adsorption on flat and curved surfaces have been studied (66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71). These studies explore the interplay of chain flexibility and attractive interactions on conformational properties of adsorbed chains. Consequently, for curved surfaces, another length scale associated with the radius of the sphere plays an important role in dictating these properties (70,72). In a different vein, sequence heterogeneity of a polymer plays a role in governing its organization in different types of solvents. Minimal hydrophobic/hydrophilic polymers have therefore been used to explore the coil-globule transition to probe native conformations of proteins (73,74). It was shown (75,76) that in addition to the fraction of the hydrophobic beads, their arrangement on the chain backbone influences their spatial organization. Further, adsorption of such heteropolymers on patterned substrates with attractive patches has been studied (77). We would like to highlight that the coupled effects of sequence heterogeneity, attractive interactions, and confinement in curved geometries has not been considered before.

Because our homopolymer model does not reproduce experimental data of domain size distributions, it motivates the need for a heteropolymer model to capture chromatin conformational properties. It is worth noting though that the exponents ν and β for mean-square displacement and contact probabilities for a homopolymer are in the same range as that of a heteropolymer. Thus, the homopolymer model serves as a benchmark against which more complex heteropolymer sequences can be compared.

Heteropolymer

A heteropolymer model for chromatin assumes NA beads of type A and NB beads of type B, such that NA/(NA + NB) = f. We consider three heteropolymer models: 1) random heteropolymer, in which the NA number of A-type beads are chosen randomly; 2) uniform block copolymer, in which the NA beads are divided into uniform patches of size p = N/4; and 3) Gaussian block copolymer, in which the NA beads are divided into patches with patch sizes chosen from a Gaussian distribution (μ = 20, σ = 5). For polymers with quenched randomness of the type studied here, the fraction f as well as the disorder correlation length plays a role in dictating their equilibrium properties. We investigate the statistical properties of the confined polymer both as a function of the lamin-binding energy as well the fraction f of binding monomers.

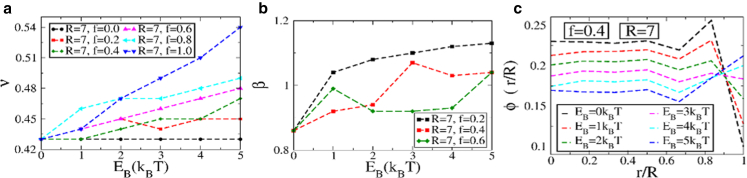

The mean-square displacement between any two monomers has the same statistical features as a homopolymer, with for small separations, followed by a saturation at larger values. The exponent ν increases as a function of EB for all fractions considered, as shown in Fig. 4 a. Increasing the binding energy EB allows the monomers to spread out on the surface as lamin attachments become more favorable, leading to an increase in the exponent ν. As expected, ν also increases while increasing the fraction f of binding monomers. A similar behavior is observed for the contact probability exponent β (Fig. 4 b). The values of the exponents ν and β are similar for the different disorder realizations studied.

Figure 4.

(a)The mean-square displacement exponent ν as a function of EB for a different fraction of binding monomers f. (b) Shown is the contact probability exponent β as a function of EB for different f. (c) Plots of the radial volume fraction are shown. All results are shown for the random heteropolymer model in a spherical cavity of R = 7. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also plot the volume fraction (Fig. 4 c) as a function of the normalized distance from the center of the sphere for a binding fraction of f = 0.4 corresponding to the biologically relevant situation (30). For small binding energies, the volume fraction drops close to the surface of the nucleus. With increasing binding energy, the volume fraction shows a maxima near the lamina, indicating an increased density of monomers there. Note that this increased volume fraction and hence tighter packing of monomers near the periphery is reminiscent of highly packed heterochromatin, as discussed earlier. For heteropolymers, this arises at high values of the binding energy, indicating that strong lamin-chromatin interactions are necessary to reproduce tighter packaging at the nuclear periphery.

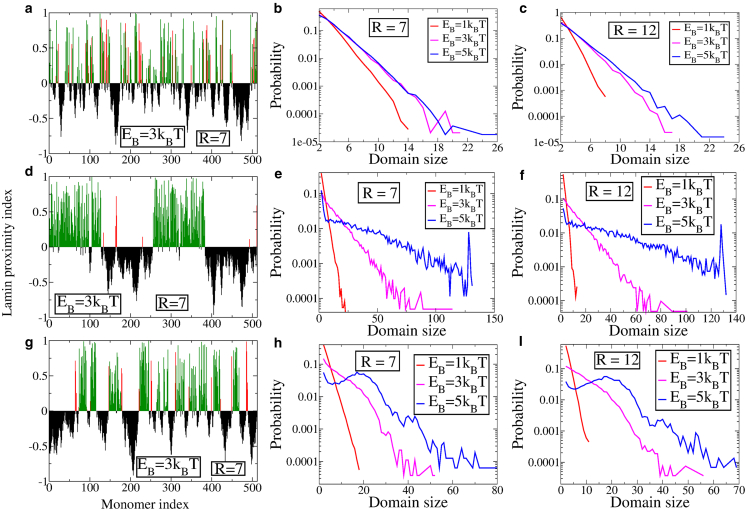

We now turn to the lamin contact maps to investigate domain formation for the heteropolymer case. A representative plot for the LPI for a random heteropolymer with f = 0.4 is shown in Fig. 5 a for R = 7 and EB = 3 kBT. Domains of lamin-associated chromatin alternate with ones that do not come in contact with the NL. The length distribution of the domains for R = 7 and R = 12 are shown in Fig. 5, b and c, respectively. The domain sizes are distributed exponentially for both values of the nuclear size, indicating that a random heteropolymer model does not reproduce the characteristic distributions of LADs observed in experiments (30). Fig. 5 d shows the LPI for the uniform block copolymer with f = 0.5 having four equal length alternating blocks of attractive and inert domains that interact with the lamin. The block copolymeric nature is reflected in the LPI plots (Fig. 5 d) with larger domain sizes in comparison to those formed in the case of the random heteropolymer. The associated domain length distributions for R = 7 and R = 12 are shown in Fig. 5, e and f, respectively. In contrast to the single exponential fit for both the homopolymer and the random heteropolymer, the domain size distribution in this case is a double exponential, with an enhanced probability for larger domains. For high enough binding energies, additionally, there is a peak corresponding to the domain size as well. Finally, we consider the case of Gaussian block heteropolymer with f = 0.4, with the corresponding LPI shown in Fig. 5 g. The distributions of the LAD sizes reflect the Gaussian nature of the block copolymer for higher values of the binding energy , as can be seen from Fig. 5, h and i for both values of the radius. This qualitatively agrees with the domain size distribution observed in DamID measurements (30). The heteropolymer model thus illustrates that the observed domain length distributions in experimental studies must necessarily correlate with the distribution of chromatin regions that can interact with lamin proteins as well as setting a scale for the strength of the lamin-chromatin interactions. Weak interactions give rise to exponential domain length distributions, and hence, the interaction energies must be beyond a certain strength to explain the experimental observations. This is also consistent with the observation that tighter packing at the nuclear periphery is observed beyond a critical lamin-chromatin interaction strength.

Figure 5.

LPI for EB = 3 kBT for a sphere with R = 7 for the three heteropolymer models: (a) random heteropolymer, (d) uniform block copolymer, and (g) Gaussian block copolymer. The red lines indicate type-B monomers that are in proximity to the NL, whereas green lines indicate bond-forming type-A monomers. The corresponding distributions of domain sizes is shown for R = 7 in (b, e, and h) and for R = 12 in (c, f, and i). To see this figure in color, go online.

Multiple polymers

We explore the formation of chromatin territories within our model. In the absence of any lamin interactions (EB = 0), the lamin contact maps (Fig. 6 a) show negligible territory formation. A sample equilibrium configuration, shown in Fig. 6 c, illustrates that there is significant interpenetration between the four polymer strands. If we allow two of the four polymers to interact with the lamin, these two polymers show extremely low levels of interpenetration. This can be seen from the contact map shown in Fig. 6 b, in which the first polymer (monomers 0–127) and the third polymer (monomers 256–383) interacts with the lamin (EB ≠ 0), whereas the other two do not. The regions of the contact map corresponding to overlaps between the first and third polymers clearly show a reduced intensity, indicating that the two polymers seldom approach each other. This is also clear in the sample equilibrium configuration shown in Fig. 6 d, in which the first (brown) and third (red) polymers stay close to the attractive surface on the two distal sides of the sphere. The two noninteracting polymers (shown here in cyan and blue), on the other hand, occupy the central region of the sphere and have increased interpenetration.

Figure 6.

(a) Contact maps and (c) sample configuration for a system of four polymers, none of which interact with lamin proteins. (b) Shown are contact maps and (d) sample configuration for a system of four polymers of which two interact with lamin proteins, whereas the other two do not. To see this figure in color, go online.

The interactions of the lamin proteins with the chromatin thus enhances the ability of the chromatin to segregate into individual territories. The attractive surface interaction makes it energetically favorable for the chromatin polymers to occupy different regions of the nucleus, leading to the formation of territories. This provides a candidate mechanism by which chromosome territories form within the eukaryotic cell nucleus.

Discussion

We model chromatin packing in the cell nucleus as a polymer confined in a spherical cavity having an attractive interaction with the inner walls. We compute statistically measurable quantities such as mean-square displacement as a function of basepair separation , the LPI, and contact map for homo- and heteropolymers with different disorder realizations and different nuclear radii. Our computational results explain the data observed in DamID and FISH experiments.

A complete map of chromatin-NL interactions generated by DamID experiments have identified a large number of LADs in the human chromosome, and understanding the origin of the observed distribution of LADs is thus important to understand the three-dimensional (3D) organization of the genome. Our work shows that a heteropolymeric chromatin, with domains of lamin-binding regions with sizes drawn from a distribution, reflects this structural heterogeneity. We show, for example, that for Gaussian distributed domains, the lengths of lamin-associated regions also follow a Gaussian distribution. Further, for low binding energies, the distribution of lengths follows a single exponential. Thus, our analysis shows that lamin-chromatin interactions need to be beyond a certain critical strength (few kBTs), such that thermal energies can compete with the interaction energy, leading to dynamic chromosomes, and also reflect the underlying domain structure.

For the case of multiple polymers, although it is known that confinement can introduce territory formation (78), we show that lamin-mediated interactions can effectively strengthen the formation of chromosome territories, even at densities in which territory formation would not be expected from simple confinement.

Although our model shows several interesting features, a quantitative understanding of genome organization is far from complete. We assumed a uniformly attractive surface, corresponding to a uniform distribution of lamin proteins. In reality, there is a complex and heterogeneous distribution of lamin filaments on the nuclear envelope, and this would lead to tighter heterochromatin packaging at regions of high lamin concentration (79). Further, A-type lamins are known to be present on the nucleolus as well (28,29). Thus, LADs on chromatin can interact with the nucleolus surface in the interior of the nucleus. The effect of this attractive surface in the nuclear interior can compete with the attractive interaction at the nuclear periphery to give rise to nontrivial structures. The current model focuses solely on the effect of nuclear lamin interactions. However, it is known that various other proteins such as CTCF (80,81), cohesins, and condensins (82, 83, 84) play a role in the large-scale organization of the genome. An open question is how protein-mediated interactions in the bulk compete with lamin interactions on the surface to determine 3D organization. These bulk interactions will also affect tighter heterochromatin packaging near the nuclear periphery. Nonequilibrium active forces may also play a role, although their role in large-scale organization remains open.

While preparing this manuscript for publication, we became aware of a similar model by Chiang et al. (85). Although our model does not include sequence-specific data as an input into hetero/euchromatin track lengths, it is more generic, allowing for systematically tuning the disorder correlation length of heterochromatin tracks along the backbone. Despite its conceptual simplicity, our model captures features of conformational statistics of the chromatin. This calls for a systematic study of specific interactions among beads and lamin to understand the robustness of the genetic landscape on changes in mesoscale parameters. We hope that our simple theoretical model will encourage experimental work in this direction. Our study predicts that tuning the strength of lamin-chromatin interactions can change the distributions of LAD lengths. If the interactions can be made sufficiently weak, the theory predicts a transition to a single exponential distribution of domain sizes. Further, tuning the interaction strength will also change the radial volume fraction, with the volume fraction at the nuclear periphery increasing monotonically with increasing interaction strength. These specific predictions can be tested against experimental data.

In summary, our work highlights the importance of a phenomenological model with a minimal number of tractable parameters that can be used to quantify lamin-associated chromatin organization. It is worth noting that the domain size distributions obtained from our model arise as a consequence of different patch sequence guided by “intuition” and are not inputs for our polymer model guided by experiments. Our study emphasizes how sequence heterogeneity in the genome affects the 3D genome organization. In particular, this heterogeneity is crucial to a complete understanding of the chromosome packaging problem. We hope that our minimal theoretical model will inspire experiments in this direction across cell types and organisms at different stages of development.

Author Contributions

M.K.M. and B.C. designed the research. A.M. carried out all simulations and analyzed the data. Preliminary simulations and analysis were carried out by J.A.A. and S.R. M.K.M., A.M., and B.C. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

Financial support is acknowledged by M.K.M. for Ramanujan Fellowship (13DST052), Department of Science and Technology, and Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (14IRCCSG009).

Editor: Tom Misteli.

References

- 1.Fraser P., Bickmore W. Nuclear organization of the genome and the potential for gene regulation. Nature. 2007;447:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature05916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanctôt C., Cheutin T., Cremer T. Dynamic genome architecture in the nuclear space: regulation of gene expression in three dimensions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:104–115. doi: 10.1038/nrg2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horowitz-Scherer R.A., Woodcock C.L. Organization of interphase chromatin. Chromosoma. 2006;115:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bystricky K., Heun P., Gasser S.M. Long-range compaction and flexibility of interphase chromatin in budding yeast analyzed by high-resolution imaging techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16495–16500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402766101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cremer T., Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:292–301. doi: 10.1038/35066075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiessel H., Gelbart W.M., Bruinsma R. DNA folding: structural and mechanical properties of the two-angle model for chromatin. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1940–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annunziato A. DNA packaging: nucleosomes and chromatin. Nat. Educ. 2008;1:26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariño-Ramírez L., Kann M.G., Landsman D. Histone structure and nucleosome stability. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2005;2:719–729. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.5.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Holde K.E., Allen J.R., Lohr D. DNA-histone interactions in nucleosomes. Biophys. J. 1980;32:271–282. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)84956-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finch J.T., Klug A. Solenoidal model for superstructure in chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:1897–1901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodcock C.L., Frado L.L., Rattner J.B. The higher-order structure of chromatin: evidence for a helical ribbon arrangement. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:42–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker J., Rippe K., Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekker J. The three ‘C’ s of chromosome conformation capture: controls, controls, controls. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:17–21. doi: 10.1038/nmeth823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oluwadare O., Highsmith M., Cheng J. An overview of methods for reconstructing 3-D chromosome and genome structures from Hi-C data. Biol. Proced. Online. 2019;21:7. doi: 10.1186/s12575-019-0094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J., Zhang Z., Wang K. 3C and 3C-based techniques: the powerful tools for spatial genome organization deciphering. Mol. Cytogenet. 2018;11:21. doi: 10.1186/s13039-018-0368-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levsky J.M., Singer R.H. Fluorescence in situ hybridization: past, present and future. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2833–2838. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giorgetti L., Heard E. Closing the loop: 3C versus DNA FISH. Genome Biol. 2016;17:215. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cremer T., Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a003889. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meaburn K.J., Misteli T. Cell biology: chromosome territories. Nature. 2007;445:379–781. doi: 10.1038/445379a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bickmore W.A. The spatial organization of the human genome. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2013;14:67–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosak S.T., Groudine M. Form follows function: the genomic organization of cellular differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1371–1384. doi: 10.1101/gad.1209304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meister P., Towbin B.D., Gasser S.M. The spatial dynamics of tissue-specific promoters during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 2010;24:766–782. doi: 10.1101/gad.559610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geyer P.K., Vitalini M.W., Wallrath L.L. Nuclear organization: taking a position on gene expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011;23:354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorova E., Zink D. Nuclear architecture and gene regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:2174–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Steensel B., Belmont A.S. Lamina-associated domains: links with chromosome architecture, heterochromatin, and gene repression. Cell. 2017;169:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solovei I., Thanisch K., Feodorova Y. How to rule the nucleus: divide et impera. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016;40:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dechat T., Gajewski A., Foisner R. LAP2alpha and BAF transiently localize to telomeres and specific regions on chromatin during nuclear assembly. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:6117–6128. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moir R.D., Yoon M., Goldman R.D. Nuclear lamins A and B1: different pathways of assembly during nuclear envelope formation in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1155–1168. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guelen L., Pagie L., van Steensel B. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kind J., van Steensel B. Stochastic genome-nuclear lamina interactions: modulating roles of Lamin A and BAF. Nucleus. 2014;5:124–130. doi: 10.4161/nucl.28825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marko J.F., Siggia E.D. Polymer models of meiotic and mitotic chromosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:2217–2231. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.11.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosa A., Everaers R. Structure and dynamics of interphase chromosomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mateos-Langerak J., Bohn M., Goetze S. Spatially confined folding of chromatin in the interphase nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3812–3817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809501106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bohn M., Heermann D.W. Diffusion-driven looping provides a consistent framework for chromatin organization. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohn M., Heermann D.W. Repulsive forces between looping chromosomes induce entropy-driven segregation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirny L.A. The fractal globule as a model of chromatin architecture in the cell. Chromosome Res. 2011;19:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10577-010-9177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicodemi M., Prisco A. Thermodynamic pathways to genome spatial organization in the cell nucleus. Biophys. J. 2009;96:2168–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbieri M., Chotalia M., Nicodemi M. Complexity of chromatin folding is captured by the strings and binders switch model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16173–16178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204799109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiariello A.M., Annunziatella C., Nicodemi M. Polymer physics of chromosome large-scale 3D organisation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29775. doi: 10.1038/srep29775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brackley C.A., Taylor S., Marenduzzo D. Nonspecific bridging-induced attraction drives clustering of DNA-binding proteins and genome organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3605–E3611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302950110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jost D., Carrivain P., Vaillant C. Modeling epigenome folding: formation and dynamics of topologically associated chromatin domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9553–9561. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Pierro M., Zhang B., Onuchic J.N. Transferable model for chromosome architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12168–12173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613607113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganai N., Sengupta S., Menon G.I. Chromosome positioning from activity-based segregation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:4145–4159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gürsoy G., Xu Y., Liang J. Spatial confinement is a major determinant of the folding landscape of human chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8223–8230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang H., Yoon Y.-G., Hyeon C. Confinement-induced glassy dynamics in a model for chromosome organization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;115:198102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.198102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang B., Wolynes P.G. Topology, structures, and energy landscapes of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506257112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brackley C.A., Johnson J., Marenduzzo D. Simulated binding of transcription factors to active and inactive regions folds human chromosomes into loops, rosettes and topological domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:3503–3512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fudenberg G., Imakaev M., Mirny L.A. Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2038–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michieletto D., Orlandini E., Marenduzzo D. Polymer model with epigenetic recoloring reveals a pathway for the de novo establishment and 3D organization of chromatin domains. Phys. Rev. X. 2016;6:041047. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shukron O., Holcman D. Statistics of randomly cross-linked polymer models to interpret chromatin conformation capture data. Phys. Rev. E. 2017;96:012503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.96.012503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banigan E.J., van den Berg A.A., Mirny L.A. Chromosome organization by one-sided and two-sided loop extrusion. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/815340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knoch T.A. Simulation of different three-dimensional polymer models of interphase chromosomes compared to experiments-an evaluation and review framework of the 3D genome organization. Semin. Cell Dev. Bio. 2019;90:19–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alberts B., Johnson A., Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Fifth Edition. Garland Science; 2008. Chapter 18 apoptosis: programmed cell death eliminates unwanted cells; p. 1115. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun H.B., Shen J., Yokota H. Size-dependent positioning of human chromosomes in interphase nuclei. Biophys. J. 2000;79:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wedemann G., Langowski J. Computer simulation of the 30-nanometer chromatin fiber. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2847–2859. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75627-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerchman S.E., Ramakrishnan V. Chromatin higher-order structure studied by neutron scattering and scanning transmission electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7802–7806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jhunjhunwala S., van Zelm M.C., Murre C. The 3D structure of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus: implications for long-range genomic interactions. Cell. 2008;133:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shopland L.S., Lynch C.R., O’Brien T.P. Folding and organization of a contiguous chromosome region according to the gene distribution pattern in primary genomic sequence. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:27–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Münkel C., Eils R., Langowski J. Compartmentalization of interphase chromosomes observed in simulation and experiment. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1053–1065. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boettiger A.N., Bintu B., Zhuang X. Super-resolution imaging reveals distinct chromatin folding for different epigenetic states. Nature. 2016;529:418–422. doi: 10.1038/nature16496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang S., Su J.-H., Zhuang X. Spatial organization of chromatin domains and compartments in single chromosomes. Science. 2016;353:598–602. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi G., Liu L., Thirumalai D. Interphase human chromosome exhibits out of equilibrium glassy dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3161. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05606-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bantignies F., Cavalli G. Polycomb group proteins: repression in 3D. Trends Genet. 2011;27:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalhor R., Tjong H., Chen L. Genome architectures revealed by tethered chromosome conformation capture and population-based modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;30:90–98. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Gennes P. Scaling theory of polymer adsorption. J. Phys. (Paris) 1976;37:1445–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eisenriegler E., Kremer K., Binder K. Adsorption of polymer chains at surfaces: scaling and Monte Carlo analyses. J. Chem. Phys. 1982;77:6296–6320. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bachmann M., Janke W. Conformational transitions of nongrafted polymers near an absorbing substrate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:058102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.058102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Birshtein T.M., Borisov O.V. Theory of adsorption of polymer chains at spherical surfaces: 2. Conformation of macromolecule in different regions of the diagram of states. Polymer (Guildf.) 1991;32:923–929. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arkin H., Janke W. Polymer adsorption on curved surfaces. Phys. Rev. E. 2017;96:062504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.96.062504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chertovich A.V., Ivanov V.A., Khokhlov A.R. Sequence design of biomimetic copolymers: modeling of membrane proteins and globular proteins with active enzymatic center. Macromol. Symp. 2001;160:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Odijk T. Physics of tightly curved semiflexible polymer chains. Macromolecules. 1993;26:6897–6902. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murnen H.K., Khokhlov A.R., Zuckermann R.N. Impact of hydrophobic sequence patterning on the coil-to-globule transition of protein-like polymers. Macromolecules. 2012;45:5229–5236. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luo M.-B., Ziebarth J.D., Wang Y. Interplay of coil-globule transition and surface adsorption of a lattice HP protein model. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:14913–14921. doi: 10.1021/jp506126d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mishra A., Panwar A.S., Chakrabarti B. Equilibrium morphologies and force extension behavior for polymers with hydrophobic patches: role of quenched disorder. Macromol. Theory Simul. 2014;23:266–278. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheligovskaya E.A., Khalatur P.G., Khokhlov A.R. Properties of AB copolymers with a special adsorption-tuned primary structure. Phys. Rev. E. 1999;59:3071. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kriksin Y.A., Khalatur P.G., Khokhlov A.R. Recognition of complex patterned substrates by heteropolymer chains consisting of multiple monomer types. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:174904. doi: 10.1063/1.2191849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jun S., Arnold A., Ha B.-Y. Confined space and effective interactions of multiple self-avoiding chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:128303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.128303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Belmont A.S., Zhai Y., Thilenius A. Lamin B distribution and association with peripheral chromatin revealed by optical sectioning and electron microscopy tomography. J. Cell Biol. 1993;123:1671–1685. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dixon J.R., Selvaraj S., Ren B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rao S.S., Huntley M.H., Aiden E.L. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee J. Roles of cohesin and condensin in chromosome dynamics during mammalian meiosis. J. Reprod. Dev. 2013;59:431–436. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2013-068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuen K.C., Gerton J.L. Taking cohesin and condensin in context. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Uhlmann F. SMC complexes: from DNA to chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiang M., Michieletto D., Chandra T. Polymer modeling predicts chromosome reorganization in senescence. Cell Rep. 2019;28:3212–3223.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]