All countries must increase medical capabilities and adopt a concerted whole‐of‐government approach to combat COVID‐19

Singapore is a densely populated city‐state of 5.7 million and a global travel hub. These characteristics make it particularly susceptible to the importation of communicable diseases and consequent outbreaks. The 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak challenged the nation's public health system and now the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic is presenting a greater challenge.

Since December 2019, the virus responsible for COVID‐19, SARS‐CoV‐2, has spread to more than 200 countries and over 4 million cases have been reported.1 Singapore diagnosed its first case on 23 January 2020.

Translating lessons from SARS to COVID‐19

In 2003, SARS infected 238 people and killed 33 in Singapore, exposing the weaknesses of the epidemiological surveillance and health care system for emerging infectious diseases.2 Learning from the outbreak, Singapore introduced several key measures to strengthen its pandemic management capabilities.

The Disease Outbreak Response System Condition framework was established. This framework serves as the foundation for the national responses to any outbreak and is divided into four levels of incremental severity (green, yellow, orange and red), based on risk assessment of the public health impact of the disease and the current disease situation in Singapore (Box 1). The goal and extent of public health response measures are in response to the level of threat.2, 3

Box 1. Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) matrix and response measures.

| Possible scenarios | Applicable response phases | Border control | Public health measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature screening in institutions | Social distancing | School closures | Contact tracing | Phone surveillance or quarantine | Antivirals | Vaccination | |||

| Green (negligible to low public health impact) | |||||||||

|

High virulence No or limited human‐to‐human transmission Disease mainly overseas |

Alert with containment of imported cases | HAN | No | No | No | Yes, if imported cases | To implement depending on risk | Treatment of cases where necessary | No |

| Similar or lower virulence and transmissibility as seasonal influenza | Mitigation | No | Consider for implementation | No | No | No | No | Treatment of cases where necessary | Vaccination for high risk groups if available |

| Yellow (low to moderate public health impact) | |||||||||

|

High virulence but low transmissibility Disease mainly overseas |

Alert with containment of imported cases |

HAN HDC Temperature screening of inbound passengers |

No | No | No | Yes, if imported cases | To implement depending on risk | Treatment of cases where necessary | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

| Local epidemic with low virulence but high transmissibility | Mitigation | HAN | Consider for implementation | No | No | No | No | Treatment of cases where necessary | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

| High virulence and transmissibility but vaccine available | Mitigation | HAN | No | No | No | No | No | Treatment of cases where necessary | Distribute vaccine to mitigate impact |

| Orange (moderate to high public health impact) | |||||||||

|

High virulence and transmissibility Disease mainly overseas |

Alert |

HAN HDC Temperature screening of inbound passengers |

No | No | No | Yes, if imported cases | Quarantine | Treatment of cases, consider limited prophylaxis of personnel providing essential services | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

|

High virulence and transmissibility Disease in Singapore |

Containment |

HAN HDC Temperature screening of inbound passengers |

Yes, depending on risk | Yes, depending on risk | Yes, selective closure if cases or clusters detected in schools | Yes, as far as operationally feasible | Quarantine, as far as operationally feasible | Treatment of cases, consider limited prophylaxis of personnel providing essential services | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

|

High virulence and transmissibility More cases in Singapore |

Limited mitigation |

HAN HDC Temperature screening of all passengers |

Yes, depending on risk | Yes, depending on risk | Yes, selective closure if cases or clusters detected in schools | No | No | Treatment of cases, consider limited prophylaxis of personnel providing essential services | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

| Red (high public health impact, widespread local transmission) | |||||||||

|

High virulence and transmissibility Widespread transmission |

Mitigation | Temperature screening of all passengers | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Treatment of cases and prophylaxis of personnel providing essential services | Procure and offer vaccines when available |

HAN = Health Advisory Notice; HDC = health declaration card.

Adapted from Singapore Ministry of Health pandemic readiness and response plan.3

Infrastructure for outbreak management was significantly augmented. Isolation facilities in public hospitals have been increased. The National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), a 330‐bed purpose‐built infectious disease management facility with integrated clinical, laboratory and epidemiological functions has replaced the 39 isolation‐bed Communicable Disease Centre as the centrepiece of pandemic management in Singapore.2, 4 National stockpiles of personal protective equipment (PPE), critical medications and vaccines for up to 6 months were established.2

Professional personnel and training of health care workers in outbreak response were expanded, with the number of infectious disease physicians rising from 11 in 2003 to 73 in 2020. Since 2006, the Singapore Ministry of Health has conducted regular 4‐yearly scenario‐based simulation exercises at all public hospitals to evaluate and provide feedback on their pandemic response plans.5

Public engagement and education were crucial components in the public health response to outbreaks. Consistent public communication was effected through press releases and media coverage of the epidemic, while an education campaign was mounted to educate Singaporeans on the disease and appropriate behaviour to prevent transmission.6

It was apparent from SARS that clear leadership and direction was essential for a government‐wide, coordinated response towards the outbreak. A ministerial committee, first established during the SARS outbreak to provide guidance and decisions on strategies for containment of the outbreak, was convened in the COVID‐19 pandemic as a multi‐ministry taskforce co‐chaired by the Minister for Health and the Minister for National Development.2, 4 This taskforce has the ability to recommend and implement whole‐of‐government policies to deal with issues related to COVID‐19.

Singapore's COVID‐19 response

To reduce the transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2, Singapore has adopted a strategy of active case detection and containment through several means.

Surveillance and containment

With the goal of identifying every case of COVID‐19, several complementary detection methods were employed. A local case definition for suspect cases of COVID‐19 was first established on 2 January 2020 based on clinical and epidemiological criteria.4, 7 This definition was constantly updated to adapt to the evolving global and local situation (Supporting Information).7 Dissemination of the criteria to all physicians in Singapore was via text messages and emails, and criteria‐based screening was implemented at all clinics and hospitals nationally. Patients fulfilling criteria were referred from primary care clinics to the NCID, while those presenting to hospital emergency departments were isolated in airborne infection isolation rooms and tested.

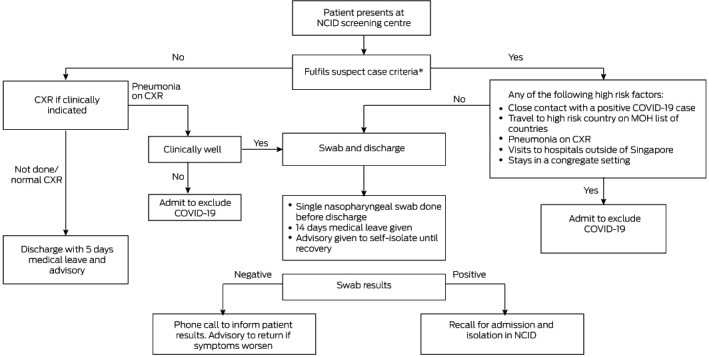

At the NCID, a purpose‐built outbreak screening centre was activated to evaluate suspect cases. Suspect cases were stratified into low and high risk groups (Box 2). High risk suspect cases were admitted, isolated and tested for SARS‐CoV‐2. Low risk suspect cases had a single nasopharyngeal swab test and were discharged with a written advisory to self‐isolate at home. Phone surveillance for symptom progression was performed and patients with persistent symptoms or positive swab results were recalled for further evaluation or isolation. On 16 March 2020, a total of 4721 low risk suspect cases had been evaluated, of whom 63 were recalled for positive test results.

Box 2. National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID) screening centre workflow.

CXR = chest x‐ray; MOH = Ministry of Health. * See Supporting Information.

Patients with confirmed COVID‐19 underwent detailed interviews for activity mapping to guide contact tracing and cluster investigations. A mobile phone application (app) was also developed by the Ministry of Health and the Government Technology Agency to facilitate contact tracing in the community. Devices with the app installed exchange anonymised proximity information by means of bluetooth relative signal strength indicator readings across time to approximate the proximity and duration of an encounter between two users. This information is then obtained by the Ministry of Health from the device of a patient, reducing the time and effort required for contact tracing.8 On 20 April, the app had achieved a 20% population adoption rate, with 1.1 million users in Singapore.9

Identified close contacts were placed in quarantine either at home or government quarantine facilities while casual contacts were placed on phone surveillance (Supporting Information).7, 10 The Infectious Diseases Act was applied to enforce epidemiological investigations and containment measures.11 On 9 March, over 4000 contacts had been placed under quarantine.4

Beyond case definition, an enhanced surveillance system was implemented to test for SARS‐CoV‐2 among all cases of community‐acquired pneumonia, severely ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs) with possible infectious disease, deaths from possible infectious aetiology, and influenza‐like illness in sentinel primary care clinics.4, 7 Doctors have the liberty to test patients based on clinical or epidemiological suspicion. At 29 February 2020, 16% of the first 100 COVID‐19 cases were detected by enhanced surveillance (15 from pneumonia surveillance and one from the ICU), while clinician‐guided testing accounted for an additional 11% of cases.7

To support multiple testing sites, SARS‐CoV‐2 reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) laboratory testing capability was expanded from the National Public Health Laboratory to all public hospitals in Singapore, allowing more than 8000 tests to be performed daily.12

Border control measures

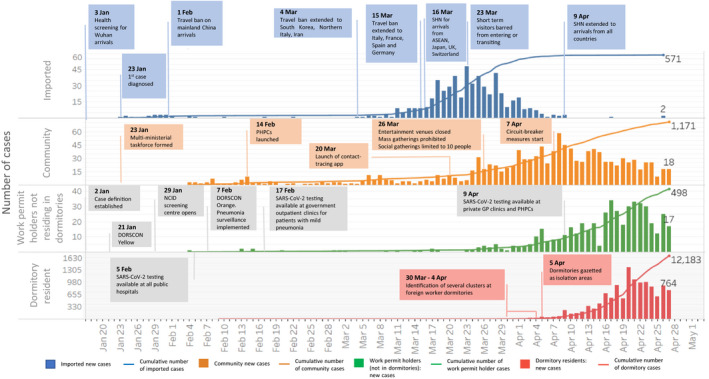

Singapore implemented border control measures to prevent importation of cases and consequent forward local transmission.4 The earliest of these measures involved temperature and health screening for arrivals from Wuhan since 3 January 2020. Measures were progressively escalated in response to the global situation, with screening measures extended to all travellers at all ports of entry since 29 January, and a travel ban for all visitors with recent travel to China from 1 February, which was extended to South Korea, Iran and Northern Italy on 4 March, and the whole of Italy, France, Spain and Germany from 15 March.

Despite these measures, the continued increase in imported cases necessitated the introduction of further measures. A mandatory 14‐day stay‐home notice at dedicated facilities was enforced on all arrivals from ASEAN countries, Japan, Switzerland and the United Kingdom from 16 March. This was further extended to arrivals from the United States on 25 March, and subsequently to all returning travellers from 9 April. All short term travellers have also been banned from entering or transiting in Singapore since 23 March, and Singapore residents have been advised to defer all non‐essential travel.

With the above measures, the daily incidence of imported cases steadily decreased from a peak of 48 cases per day on 23 March to zero cases per day since 10 April13 (Box 3).

Box 3. Epidemiological timeline of COVID‐19 in Singapore, and major public health measures.

DORSCON = Disease Outbreak Response System Condition; PHPC = Public Health Preparedness Clinic; SHN = stay‐home notice. Adapted from Ministry of Health Singapore. Situation report – 27 April 2020: coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/2019-ncov/situation-report—27-apr-2020.pdf (viewed Apr 2020).

Community and social measures

Drawing from the public engagement efforts in SARS, public education efforts in Singapore emphasised social responsibility and appropriate behaviour. Messages on regular handwashing, appropriate use of masks when unwell, seeking medical treatment early and staying home when unwell were conveyed through print and broadcast media as well as social media platforms.4 The public was advised to obtain accurate and factual information from reliable sources including government websites, Facebook and Instagram.4

Daily updates on the COVID‐19 situation with anonymised information on positive cases were shared publicly though the Ministry of Health website while misinformation was quickly dispelled to prevent public anxiety and speculation.4

Singaporeans with respiratory symptoms were encouraged to seek treatment at Public Health Preparedness Clinics, a network of over 800 primary health clinics that provide subsidised care and extended medical leave of up to 5 days. This allowed possible mild COVID‐19 cases to self‐isolate at home and reduce community transmission. Those with progressive symptoms were advised to return to the same doctor for evaluation and further testing.4

At the workplace, employers were encouraged to conduct regular temperature and health monitoring for employees, as well as to implement business continuity plans, such as working from home or segregated teams to reduce mixing of workers. Fever screening through thermal scanners was implemented at points of entry of most buildings and facilities.4 From 26 March, entertainment venues were closed and large scale gatherings were cancelled.

However, with the rising number of locally acquired cases in the community as well as the emergence of large clusters within foreign worker dormitories in early April, a set of “circuit‐breaker” measures was implemented from 7 April. All non‐essential workplaces were closed, schools were physically closed but moved to home‐based learning, and food establishments were only allowed to provide take‐away and delivery services.14

There are about 1 million lower wage foreign workers on work permit in Singapore. About 300 000 live at close quarters in densely populated dormitories. Specific measures were needed to curtail the spread of disease within these dormitories. Movement of workers in and out of the dormitories was prohibited and these dormitories were gazetted as isolation facilities. Asymptomatic workers were relocated to other facilities for quarantine, while medical facilities and triage clinics were set up within the dormitories to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic workers. Workers who tested positive were transferred to community isolation facilities if they had mild symptoms, or to the NCID and public hospitals for further treatment and isolation. To limit transmission within the dormitories, safe distancing measures were implemented to prevent intermingling of workers, including regulating access to common areas and recreation facilities, limiting workers to their rooms, and delivering meals to the rooms. Cleaning and sanitation regimes were also intensified.15, 16

Management of COVID‐19 in the National Centre for Infectious Diseases

Patients in the NCID were placed in individual negative pressure isolation rooms and reviewed daily by medical teams. The workforce was augmented by trained staff deployed from Tan Tock Seng Hospital, a university teaching hospital. Business‐as‐usual operations at the hospital were scaled down to provide both clinical and non‐clinical staff for national outbreak response.

A structured just‐in‐time training program was rolled out by the infection prevention and control department to train newly deployed staff in PPE use. To standardise the collection of clinical and epidemiological data, and guide clinical management, COVID‐19 clinical pathways were implemented.

All admitted suspect cases received an initial chest x‐ray and were tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 by means of RT‐PCR from respiratory specimens over two consecutive days.17 Clinicians were given the liberty to perform additional tests based on clinical or epidemiological grounds. Suspect cases were de‐isolated or discharged if they fulfilled the in‐house discharge criteria.18

Patients who tested positive were managed as inpatients until their symptoms had resolved and they had one negative nasopharyngeal swab result per day on two consecutive days. A wearable continuous patient monitoring system was used to monitor patient parameters to reduce health care worker exposure and PPE use. As standard of care, complete blood counts and kidney and liver function tests were performed, and C‐reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase levels were measured. Respiratory samples were tested for influenza and other respiratory viruses with a multiplex PCR assay. All patients received supportive therapy, including supplemental oxygen when needed. Patients clinically suspected of having community‐acquired pneumonia received empirical antibiotics and oral oseltamivir.19 Agents with possible antiviral effect on SARS‐CoV‐2 were offered to patients meeting in‐house guidelines. Co‐formulated lopinavir–ritonavir (200 mg/100 mg twice daily orally for up to 14 days) with or without interferon beta‐1b (8 million units every other day for 14 days) was prescribed to selected patients who required oxygen supplementation or had pneumonia, after shared decision making and provision of verbal informed consent.

Patients with risk factors for severe disease and requiring supplementary oxygen were referred to a multidisciplinary ICU team, comprising critical care and infectious disease specialists.20, 21 Patients expected to deteriorate were pre‐emptively transferred to the dedicated outbreak ICU for monitoring. Intubation, if required, was performed electively in full PPE. Non‐invasive ventilation was disallowed to reduce generation of aerosol. On‐site extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support was available for patients assessed to be suitable.22

To cope with the emergence of large number of foreign worker dormitory cases, the NCID ramped up its bed capacity to 586 beds, beyond the predetermined number of 330, through cohorting of positive cases. Patients assessed as having mild symptoms and no risk factors for disease progression were transferred to community isolation facilities until they could be de‐isolated and discharged, while those with risk factors or moderate to severe disease continued to be managed in the NCID. As of 27 April, 11 863 of 13 314 patients had been transferred to the community isolation facility.13 ICU facilities have been ramped up in anticipation of an increase of severe cases; however, the current proportion of patients requiring ICU care remains low. For instance, on 27 April, 20 of 13 314 (0.15%) positive patients were in ICUs. This is likely due to the majority of foreign workers being under 30 years of age and having mild disease.13

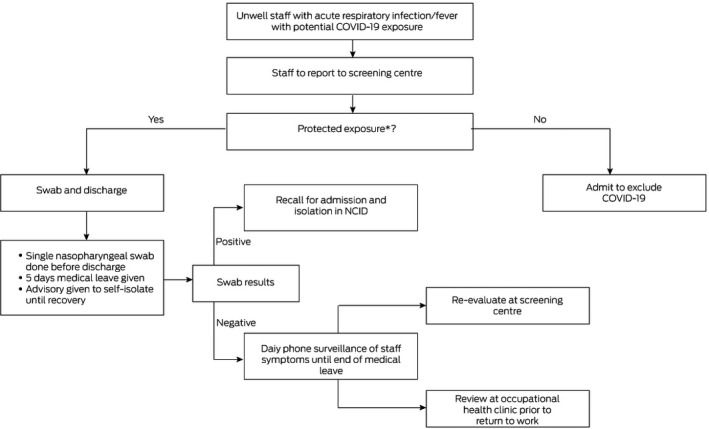

Managing sick health care workers

Since the transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 to health care workers was reported on 20 January 2020,23 twice‐daily temperature monitoring was mandated for all frontline health care workers in all public hospitals. Health care workers in direct contact with COVID‐19 patients who developed fever or symptoms of acute respiratory infection were encouraged to declare their symptoms to their superiors and present themselves to the screening centre, to be managed based on their exposure risk (Box 4). A health care worker with protected exposure was defined as one who was, at least, wearing a surgical mask. If symptomatic, the health care worker was tested, given 5 days of medical leave and placed under phone surveillance for symptom progression. Those with unprotected exposure were quarantined if asymptomatic, while those with symptoms were managed as high risk suspect cases. Before returning to work, health care workers who tested negative and had completed the duration of medical leave, were assessed at the occupational health clinic for resolution of symptoms. As of 30 April, a total of 1309 health care workers had been evaluated, of whom 69 had been admitted and 8 (0.8%) had tested positive.

Box 4. National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID): unwell health care worker workflow.

* Protected exposure: at least, wearing a surgical mask.

Beyond COVID‐19

These strategies aimed to delay the peak in number of COVID‐19 cases in Singapore and avoid overwhelming the health care system, which may have contributed to high case fatality rates in Hubei, China and Italy.24 Flattening the curve buys time for additional measures to be put in place. Adequate time is needed for purchase of equipment, health care worker deployment, logistical arrangement and operational planning. In our experience, about 10% of patients are admitted to the ICU. Increase in requirement for ICU beds is anticipated. Planning for such additional resources should be guided by experience and evidence, and adjustments must be made in an agile manner. To deal with the numbers of positive cases admitted under current policy, those with low risk and mild disease should be identified using predictive scores for subsequent safe transition of care to the outpatient setting to free up hospital resources to manage patients with severe disease.

As valuable medical resources are diverted to manage the pandemic, it is important to maintain an acceptable level of care for patients with other medical conditions. Clinic sessions that were disrupted and elective surgeries that were delayed should be ramped up to clear the backlog of patients requiring care.25 COVID‐19 impacted the training of medical students and junior doctors as cross‐institutional staff movement was restricted and lectures and bedside tutorials were cancelled.26, 27, 28 These were somewhat mitigated by online learning.

With no signs of the pandemic abating, all countries must increase medical capabilities to deal with the surge in patients. A concerted whole‐of‐government approach is paramount to combat COVID‐19, as its impact is not just on human health. Social unrest, political instability, economic depression and food security are potential issues that may further threaten our wellbeing.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supporting information

Supplementary table

The unedited version of this article was published as a preprint on mja.com.au on 6 April 2020

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐2019): situation report – 99 (28 April 2020). https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200428-sitrep-99-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=119fc381_2 (viewed Apr 2020).

- 2. Goh KT, Cutter J, Heng BH, Ma S, et al. Epidemiology and control of SARS in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006; 35: 301–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ministry of Health Singapore . MOH pandemic readiness and response plan for influenza and other acute respiratory diseases (revised April 2014). Singapore: MOH, 2014. https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/diseases-updates/interim-pandemic-plan-public-ver-_april-2014.pdf (viewed May 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee VJ, Chiew CJ, Khong WX. Interrupting transmission of COVID‐19: lessons from containment efforts in Singapore. J Travel Med 2020; 27: taaa039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lum LHW, Badaruddin H, Salmon S, et al. Pandemic preparedness: Nationally‐led simulation to test hospital systems. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2016; 45: 332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deurenberg‐Yap M, Foo LL, Low YY, et al. The Singaporean response to the SARS outbreak: knowledge sufficiency versus public trust. Health Promot Int 2005; 20: 320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ng Y, Li Z, Chua YX, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of surveillance and containment measures for the first 100 patients with COVID‐19 in Singapore – January 2‐February 29, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69: 307–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Team TraceTogether . How does TraceTogether work? https://tracetogether.zendesk.com/hc/en-sg/articles/360043543473-How-does-TraceTogether-work‐ (viewed Apr 2020).

- 9. Team TraceTogether . 20 April 2020 – one month on. https://tracetogether.zendesk.com/hc/en-sg/articles/360046475654-20-April-2020-One-Month-On (viewed Apr 2020).

- 10. Pung R, Chiew CJ, Young BE, et al. Investigation of three clusters of COVID‐19 in Singapore: implications for surveillance and response measures. Lancet 2020; 395: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Government of Singapore . Infectious Diseases Act (Chapter 137). https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/IDA1976 (viewed May 2020).

- 12. Ministry of Health Singapore . Scaling up of COVID‐19 testing. 27 Apr 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/scaling-up-of-covid-19-testing (viewed Apr 2020).

- 13. Ministry of Health Singapore . Situation report – 27 April 2020: coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/2019-ncov/situation-report—27-apr-2020.pdf (viewed Apr 2020).

- 14. Ministry of Health Singapore . Circuit breaker to minimise further spread of COVID‐19. 3 Apr 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19 (viewed Apr 2020).

- 15. Government of Singapore . Containing COVID‐19 spread at foreign worker dormitories. 14 Apr 2020. https://www.gov.sg/article/containing-covid-19-spread-at-foreign-worker-dormitories (viewed Apr 2020).

- 16. Government of Singapore . Tackling transmissions in migrant worker clusters 22 Apr 2020. https://www.gov.sg/article/tackling-transmissions-in-migrant-worker-clusters (viewed Apr 2020).

- 17. Lee TH, Lin RJ, Lin RTP, et al. Testing for SARS‐CoV‐2: can we stop at two? Clin Infect Dis 2020; 10.1093/cid/ciaa459 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tay JY, Lim PL, Marimuthu K, et al. De‐isolating COVID‐19 suspect cases: a continuing challenge. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 10.1093/cid/ciaa179 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Singapore. JAMA 2020; 10.1001/jama.2020.3204 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maclaren G, Fisher D, Brodie D. Preparing for the most critically ill patients with COVID‐19: the potential role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. JAMA 2020; 323: 1245–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid‐19 in Italy – ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic's front line. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1873–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee ZD, Chyi Yeu DL, et al. COVID‐19 and its impact on neurosurgery: our early experience in Singapore. J Neurosurg 2020; 10.3171/2020.4.jns201026 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wong C, Tay W, Hap X, Chia F. Love in the time of coronavirus: training and service during COVID‐19. Singapore Med J 2020; 10.11622/smedj.2020053 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans DJR, Bay BH, Wilson TD, et al. Going virtual to support anatomy education: a STOP GAP in the midst of the Covid‐19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ 2020; 10.1002/ase.1963 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liang ZC, Ooi SBS, Wang W. Pandemics and their impact on medical training: lessons from Singapore. Acad Med 2020; 10.1097/acm.0000000000003441 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table