To the Editor,

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and diseases (STDs) affect millions of people every year worldwide. 1 In Italy, data are provided by the Italian National Institute of Health (INIH) and reported to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). 2 , 3 In 1991 and 2009, the Italian sentinel surveillance system was established, consisting in 25 public centres (12 clinical, 13 laboratories) on the national field for diagnosis, treatment and data transmission to the INIH. 4 The STDs service of Dermatology, Bologna belongs to it and is a free‐access service (7.30–11 am) from Monday to Friday, with a patient flow of 50 patients/day.

As consequence of the COVID‐19 emergency, the Ministerial Decree limited the circulation in Italy from 9 March 2020 to 3 April 2020. 5 Thus, after the lockdown, the number of accesses was reduced to a maximum of 30 accesses/day.

We conducted a prospective observational study collecting age, sex, type of sexual relationship and diagnostic question for each patient referring to the service. Then, we compared data with those of the 4 weeks before the lockdown (20 February to 6 March 2020). We used the chi‐square test for categorical variables (gender, diagnostic question and sexual orientation) and the t‐test for continuous variables (age).

After the lockdown, 200 patients attended the service, with an average flow of 10 patients/day. Patients' age ranged from 18 to 77 years. Concerning sexual orientation, 122 (61%) were heterosexual, 75 (37.5%) homosexual and 3 (1.5%) bisexual. Compared with the patients before the lockdown, they were more likely to be male (75.5% vs. 64.6, χ2 = 14.8, P < 0.001), MSM (37.5% vs. 28.8%, χ2 = 22.6, P < 0.001) and significantly older (35.4 vs. 33.1 years, t‐test = 2.47, P = 0.018; Table 1). Before and after the lockdown patients from 15 to 49 years accounted for 88.6% and 85% but, among them, those from 15 to 24 years declined from 27.3 to 15.5% (χ2 = 12.3, P < 0.001) and, after the lockdown, the youngest patient was 18‐year‐old, while before he/she was 15‐year‐old.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics and medical provisions before and after the lockdown

| Patients' characteristics | Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the lockdown | After the lockdown | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| F | 374 | 35.4 | 48 | 24.0 |

| M | 682 | 64.6 | 151 | 75.5 |

| M/F | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Type of sexual relationship | ||||

| MSM | 297 | 28.1 | 75 | 37.5 |

| MSW | 381 | 36.1 | 77 | 38.5 |

| MSW/MSM | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| WSM | 371 | 35.1 | 45 | 22.5 |

| WSW | 7 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| WSW/WSM | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Homosexual | 304 | 28.8 | 75 | 37.5 |

| Heterosexual | 752 | 71.2 | 122 | 61.0 |

| Bisexual | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Total | 1056 | 100.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| Medical provisions | ||||

| Prophylaxis | 362 | 33.5 | 28 | 13.1 |

| Lab tests withdrawal | 274 | 25.3 | 52 | 24.3 |

| Syphylis (diagnosis, therapies, follow‐ups) | 43 | 4.0 | 18 | 8.4 |

| Chlamydia (urethritis and cervico‐vaginitis) | 21 | 1.9 | 8 | 3.7 |

| Chlamydia (proctitis) | 15 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Chlamydia (pharyngitis) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Neisseria (urethritis and cervico‐vaginitis) | 18 | 1.7 | 7 | 3.3 |

| Neisseria (proctitis) | 8 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Neisseria (pharyngitis) | 4 | 0.4 | 6 | 2.8 |

| Unspecified urethitis | 34 | 3.1 | 9 | 4.2 |

| Molluscum contagiosum | 10 | 0.9 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Genital warts | 101 | 9.3 | 22 | 10.3 |

| Candida balano‐posthites | 32 | 3.0 | 9 | 4.2 |

| Vulvo‐vaginitis | 37 | 3.4 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Genital herpes | 23 | 2.1 | 9 | 4.2 |

| Other | 99 | 9.2 | 33 | 15.4 |

| Total | 1081 | 100.0 | 214 | 100.0 |

Prophylaxis, includes blood test examination for HIV, HBV, HCV, syphilis and/or urine PCR analysis for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. WSM, Women who have sex with men.

A total of 214 medical provisions were recorded after the lockdown: 13 patients required more than one healthcare service. The most common were prophylaxis (N = 28) and medical reports withdrawal (N = 52), accounting for 37.4%. Furthermore, consultations were for genital warts (N = 22, 10.3%), syphilis‐related issues (N = 18, 8.4%), Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections (N = 17, 8%), Chlamydia thrachomatis (N = 13, 6.1%), non‐Neisseria and non‐Chlamydia urethritis (N = 9, 4.2%), Candida balano‐posthites (N = 9, 4.2%), genital herpes (N = 9, 4.2%), molluscum contagiosum (N = 3, 1.4%), Candida vulvo‐vaginitis (N = 2, 0.9%; Table 1). The remaining 33 medical provisions (15.4%) not included in the former categories, and defined as Other, encompass STIs‐related and non‐STIs‐related issues, as therapeutic counselling and pathologies involving genital area (inflammatory diseases, or diagnostic workup).

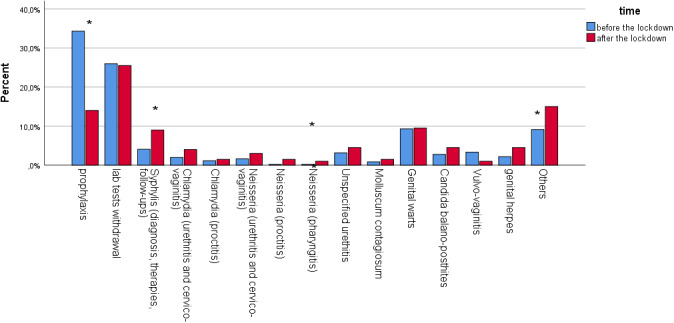

Before the lockdown, a total of 1081 medical provisions were delivered. The percentage of visits for prophylaxis declined after the lockdown, while visits for syphilis, gonococcal pharyngitis and inflammatory genital diseases increased significantly (Fig. 1). The percentage of patients requiring more than one provision increased from 2.1 to 6.5%, after the lockdown.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of the type of service delivered in the two time periods: before and after the lockdown. (Asterisks denote significant differences).

Patients characteristics and medical provisions before and after the lockdown were consistent with the literature. 3 , 6 , 7 However, the percentage of men who have sex with men (MSM) recorded remained higher than the national trends, (28.8% vs. <20%). 2 , 4 Moreover, the profile of patients and the type of medical provisions required changed. Whether this is due to a real decline of sex‐related risk or if it is only a consequence of the fear of referring to hospitals, is unknown. Some Italian cardiologists, indeed, showed that during the lockdown the diagnostic delay of myocardial infarctions and cardio‐vascular emergencies increased, leading to higher mortality/morbidity, especially when a timely intervention would have led to better outcomes. 8 This is an open scenario and further information is required.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding sources

None declared.

References

- 1. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64(RR‐03): 1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salfa MC, Ferri M, Suligoi B. Rete Sentinella dei Centri clinici, Laboratori di microbiologia clinica per le Infezioni Sessualmente Trasmesse. Not Ist Super Sanità 2019; 32: 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Long‐term Surveillance Strategy 2014–2020, ECDC, Stockholm, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salfa MC, Regine V, Giuliani M, et al. La Sorveglianza delle Infezioni Sessualmente Trasmesse basata su una Rete di Laboratori: 16 mesi di attività. Not Ist Super Sanità 2010; 23:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2020/03/08/59/sg/pdf (last accessed: 08 March 2020).

- 6. World Health Organization . Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections: Overview and Estimates. Geneva, 2001. URL http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/who_hiv_aids_2001.02.pdf (last accessed: November 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tarantini L, Navazio A, Cioffi G, Turiano G, Colivicchi F, Gabrielli D. Being a cardiologist at the time of SARS‐COVID‐19: is it time to reconsider our way of working? G Ital Cardiol 2020; 21: 354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgement

None.