Abstract

Introduction

Covid‐19 has ushered in drastic changes to the healthcare system in order to “flatten the curve”; in particular, surgical operations that can consume vital, limited resources, not to mention the risk to staff, anesthesiologists, and surgeons. However, under unique circumstances with diligent preparation, vital oncologic operations can be performed safely.

Methods

Prospective comparison of surgical cases during the pandemic from December 2019 to May 2020 to the correlating time frame from December 2018 to May 2019.

Results

A significant decline in case volume was not appreciated until the United States declared a national state of emergency, allowing patients with cancer to continue to undergo curative tumor resection until then (428.3 ± 51.5 vs 166.6 ± 59.8 cases/week; P < .001). The decrease was consistent with the mean case volume during the holidays (213.8 ± 76.8 vs 166.6 ± 59.8 case/week; P = .648). Evaluation of surgical subspecialties demonstrated a significant decrease for all subspecialties with the greatest decline in sarcoma (P = .002) and endocrine (P = .001) surgeries, while vascular (P = .004) and thoracic (P = .011) surgeries had the least.

Conclusions

The novel coronavirus has drastically reduced oncologic operations, but with proper evaluation of patients and allocation of resources, surgery can be performed safely without compromising the aim to flatten the curve and control the coronavirus pandemic.

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, Covid‐19 and oncologic surgery

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus (Covid‐19) was first documented on 31 December 2019 in Wuhan, China with its initial index cases, followed by the first death on 11 January 2020. From there, the virus quickly engulfed the province and spread at unprecedented rates across the globe. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The family of coronaviruses has a predilection for cross infection between humans and other zoonotic species, in this case bats, which culminated in viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome, which humanity has never encountered in the past. 5 , 6 Covid‐19 presents with a cluster of pneumonia‐like symptoms, often nonspecific including fever, malaise, nonproductive cough, and dyspnea, but can progress rapidly, in approximately 5.3 days, to acute respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation with a high mortality rate. 7 , 8

On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global state of emergency and named the novel coronavirus Covid‐19 on 11 February as the virus spread across the world from China to South Korea and Iran, and then Italy and eventually to the United States with the first case documented in Seattle, Washington on 20 January 2020. 9 With the massive outbreak that then ensued, the United States quickly surpassed other nations becoming the country with the most confirmed cases leading to restrictions and mandates from the Surgeon General and the American College of Surgeons canceling nonemergent surgeries and social distancing even in the hospital setting. 10 , 11 With increasing data showing risks of patients undergoing surgery during the pandemic, potentially operating on infected patients, serious consideration was necessary to determine which operations are nonelective and justify the potential risks to patients, surgeons, anesthesiologists, nursing staff, and also taking into account the limited protective equipment and proper allocation of those resources.

In light of these serious considerations, difficult decisions are necessary at an institution that exclusively cares for patients with cancer. While there are recommendations for proper precautions, implementation of such protocols is hospital‐dependent and based on the available protective equipment and also the patient population. 12 There is a relative paucity of studies examining the impact of Covid‐19 on surgical treatment of malignancy. 13 The authors report on the effects of Covid‐19 on surgical procedures at a tertiary care cancer center, and demonstrate that oncologic surgery can be performed safely for patients needing surgical extirpation for treatment of their malignancies.

2. METHODS

A prospective log was compiled of cases on a weekly basis since the WHO declared a global state of emergency secondary to the novel coronavirus, and a retrospective review was performed of all surgical cases dating to first documented case of Covid‐19. To correct for the impact of the holidays on operative volume, the review was performed at the start of December 2019 since the first Covid‐19 cases were reported toward the end of the month during the holiday season. For comparison, analysis of the same correlating weeks 1 year ago was also performed to serve as a control.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations were used to summarize the volumes of surgical cases for different time periods. One‐way analysis of variance has been used to compare the surgical case volumes among normal time, holidays, and Covid‐19 pandemic. Pairwise comparisons were performed to identify the difference in surgical volumes between holidays and Covid‐19 pandemic. The Bonferroni method is used to adjust the multiple comparisons. Box–whisker plot and bar plot were applied to visualize the trend of surgical case volumes alone with timeline. All tests are two‐sided and P < .05 is considered statistically significant. All analysis were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

2.2. Timeline

With the Surgeon General's announcement, along with recommendations from national societies, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center commenced reducing operative procedures and eliminated all elective cases on 16 March 2020. The initiative to conserve resources and reduce operative volume was further enforced with Texas Executive Order GA‐09 on 24 March that prohibited all operations “not immediately medically necessary to correct a serious medical condition of, or to preserve the life of, a patient who without immediate performance of the surgery or procedure would be at risk for serious adverse medical consequences or death, as determined by the patient's physician.”

As a precaution, a number of regulations were implemented to minimize risks to patients and staff being cognizant of limited resources. All cases were reviewed by departmental oversight committees to determine the validity of scheduled cases to remain in compliance with federal, Texas state, and institution mandates. Patients presenting to the institution for consultation were seen alone to minimize traffic through the outpatient clinics, and all patients presenting for routine follow‐up appointments were rescheduled. While not endorsed by the United States Center for Disease Control, the institution implemented temperature screening of all persons entering the institution, and also required wearing of masks for everyone on campus starting on 26 March. To conserve protective N95 masks, only personnel participating in high‐risk operations involving the airway and pulmonary tract, oropharynx, and requiring tracheostomies were issued proper protective equipment, and all patients undergoing those operations were tested. However, starting 6 April, all patients undergoing surgery were tested for Covid‐19. Any patient who traveled to the institution beyond 150 miles was also required to concede to a 14‐day quarantine before entering the institution.

3. RESULTS

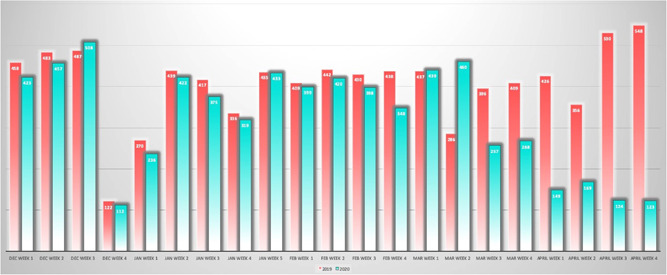

Comparison of operative volume demonstrated a dramatic decrease in the total number of cases over time since the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic. However, during the initial phases of Covid‐19, there was no change until the WHO declared the novel coronavirus a pandemic. The initial decline in surgeries coincided with spring break (16‐20 March 2020) when the case volume was typically lower than usual and was concurrent with the Surgeon General's declaration to limit elective operations. While the number of operations were lower during the pandemic, they were not statistically different than average case volume during the holidays (213.8 ± 76.8 cases/week vs 166.6 ± 59.8 cases/week; P = .648). The difference became more pronounced in the weeks after spring break through the end of April. The trend and comparison of total case volume is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction on the trend of operative cases from December to the end of April for 2018 to 2019 (red) and 2019 to 2020 (blue) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

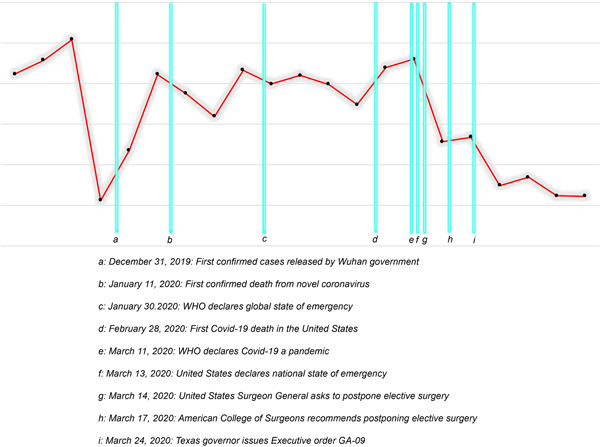

Analysis performed comparing the case volume based on specific time points in the development of the coronavirus pandemic (Figure 2) demonstrated significant decline in case volume only after the national state of emergency was declared. Landmark time points were selected for comparison including the first confirmed death from Covid‐19 (b), WHO declaration of global state of emergency (c), WHO declares Covid‐19 a pandemic (e), and following United States declaration of national state of emergency and restrictions on elective surgery (f‐g). After the declaration of a national state of emergency, the decline in cases per week was significantly lower than baseline and the previous year (428.3 ± 51.5 vs 166.6 ± 59.8 cases/week; P < .001).

Figure 2.

Landmark time points were selected for comparison including the first confirmed death from Covid‐19 (b), World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of global state of emergency (c), WHO declares Covid‐19 a pandemic (e), and following United States declaration of national state of emergency and restrictions on elective surgery (f‐g). A statistically significant decrease in total case volume only occurred following timepoint (f) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Subgroup analysis of the different surgical specialties also saw a global decrease in the number of cases performed by each service mirroring the findings in the total number of cases performed each week (Table 1). There was no surgical subspecialty that did not demonstrate a significant decrease in case volume. The service that demonstrated the most drastic reduction in cases was sarcoma (2.5 ± 1.6 vs 0.2 ± 0.4 cases/week; P = .002) followed by endocrine (9.8 ± 4.2 vs 1.6 ± 1.9 cases/week; P = .001) surgery. Of note, the volume of sarcoma cases at baseline are relatively lower given the rarity of disease, but other higher volume services were also found to have a drastic reduction in case volume such as hepatobiliary cases (10.8 ± 4.1 vs 2.4 ± 2.2 cases/week; P = .001) and liver (7.6 ± 2.4 vs 1.8 ± 0.8 cases/week; P = .001). The service that was the least affected was vascular surgery (33.5 ± 7 vs 22.2 ± 4.5 cases/week; P = .004) and thoracic surgery (20.4 ± 5.6 vs 12.0 ± 4.5 cases/week; P = .011).

Table 1.

Comparison of mean case volume from normal baseline number of cases between 2018 and 2019 and normal 2019 to 2020 to coronavirus pandemic timeframe (landmark f‐g: after 13 March 2020)

| Variable | Landmark f‐g | Mean ± STD | Median (range) | IQR | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Normal | 428.3 ± 51.5 | 430 (319‐548) | 399‐457 | <.001 |

| Covid‐19 | 166.6 ± 59.8 | 149 (123‐268) | 124‐169 | … | |

| Sarcoma | Normal | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 3 (0‐7) | 1‐4 | .002 |

| Covid‐19 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0 (0‐1) | 0‐0 | … | |

| Endocrine | Normal | 9.8 ± 4.2 | 10 (2‐22) | 7‐13 | .001 |

| Covid‐19 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1 (0‐5) | 1‐1 | … | |

| Hepatobiliary | Normal | 10.8 ± 4.1 | 11 (1‐19) | 9‐14 | .001 |

| Covid‐19 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 1 (1‐6) | 1‐3 | … | |

| Liver | Normal | 7.6 ± 2.4 | 8 (2‐12) | 6‐10 | .001 |

| Covid‐19 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2 (1‐3) | 1‐2 | … | |

| Dental | Normal | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2 (1‐17) | 1‐4 | .012 |

| Covid‐19 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0 (0‐3) | 0‐1 | … | |

| Plastic_Surgery | Normal | 42.2 ± 17.3 | 37 (22‐96) | 29‐50 | .001 |

| Covid‐19 | 11.8 ± 9.9 | 10 (4‐28) | 4‐13 | … | |

| Gyn | Normal | 25.7 ± 6.2 | 25 (14‐40) | 21‐29 | <.001 |

| Covid‐19 | 7.8 ± 4.9 | 7 (4‐16) | 4‐8 | … | |

| Pedi | Normal | 3.8 ± 2.1 | 4 (0‐8) | 2‐5 | .013 |

| Covid‐19 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1 (0‐3) | 0‐2 | … | |

| Surg_Onc | Normal | 9.2 ± 3.2 | 10 (4‐16) | 7‐11 | <.001 |

| Covid‐19 | 3 ± 1 | 3 (2‐4) | 2‐4 | … | |

| Urology | Normal | 81.3 ± 13.9 | 80 (46‐109) | 73‐94 | <.001 |

| Covid‐19 | 26.6 ± 10.7 | 21 (19‐44) | 19‐30 | … | |

| Neurosurgery | Normal | 23.4 ± 5 | 23 (12‐35) | 21‐27 | .002 |

| Covid‐19 | 7.8 ± 8.7 | 4 (1‐22) | 2‐10 | … | |

| Head_and_Neck | Normal | 47.7 ± 9.4 | 48 (31‐70) | 41‐53 | <.001 |

| Covid‐19 | 17 ± 7 | 14 (11‐29) | 14‐17 | … | |

| Breast | Normal | 41.6 ± 8.6 | 40 (26‐67) | 34‐45 | .010 |

| Covid‐19 | 17.8 ± 14.7 | 11 (10‐44) | 11‐13 | … | |

| Colorectal | Normal | 21.6 ± 5.9 | 22 (11‐32) | 18‐27 | .001 |

| Covid‐19 | 10.2 ± 2.5 | 10 (8‐14) | 8‐11 | … | |

| Orthopedic | Normal | 15.2 ± 4.6 | 16 (2‐22) | 13‐18 | .002 |

| Covid‐19 | 7.4 ± 2.1 | 7 (5‐10) | 6‐9 | … | |

| Ophthalmology | Normal | 10.8 ± 4.2 | 12 (2‐16) | 9‐14 | .026 |

| Covid‐19 | 5.6 ± 4.3 | 6 (0‐11) | 3‐8 | … | |

| Melanoma | Normal | 17.8 ± 6.1 | 18 (1‐30) | 15‐22 | .005 |

| Covid‐19 | 9.4 ± 2.9 | 9 (6‐14) | 9‐9 | … | |

| Thoracic | Normal | 20.4 ± 5.6 | 21 (7‐30) | 18‐25 | .011 |

| Covid‐19 | 12 ± 4.5 | 10 (9‐20) | 10‐11 | … | |

| Vascular | Normal | 33.5 ± 7 | 34 (19‐48) | 29‐39 | .004 |

| Covid‐19 | 22.2 ± 4.5 | 24 (16‐26) | 19‐26 | … |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

4. DISCUSSION

The novel coronavirus has forced the United States and all nations around the world to adapt their healthcare system and strategies to care for patients undergoing surgery as well as the potential threat of patients with Covid‐19. With cases reported abroad during the initial outbreak, the case volume was not affected and remained stable until just before federal restrictions were passed. However, despite mandates to reduce operative volume to conserve resources, there are clearly surgeries that cannot be postponed or delayed without compromising patient care. In the setting of cancer, our institution is in a unique circumstance where many operations are coordinated with induction or neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, and delaying surgery can have catastrophic consequences. The preliminary review of operative volume demonstrates a significant reduction in the number of total operations performed when federal policies mandated restrictions allowing us to continue care for patients. However, to provide care for patients who are typically older, with multiple comorbidities, and may be immunocompromised from radiation or chemotherapy, more stringent regulations were necessary and enforced to maintain the safety to patients and providers. As such restrictions were placed to limit visitors in the clinic as well as inpatient wards, masks were mandated for everyone, and temperature screening was performed everyone upon entry to the institution. Travel was restricted for all employees including faculty, and patients were quarantined if they traveled more than 150 miles to the hospital again to limit risks of spreading the coronavirus. With these measures, critical surgeries were performed safely without subjecting patients or staff to risks or jeopardizing patients' cancer care, but also preserving resources in anticipation of a surge of Covid‐19 cases.

Fortunately, the initial mandates to cancel elective operations coincided with school holidays, and during the week of spring break, the case volume is typically lower. However, the week after spring break, the operating room census typically returns to the baseline volumes which did not happen this year. In the ensuing weeks, a global decline in cases across all surgical subspecialties occurred demonstrating a team effort to minimize risks to patients, healthcare employees, and to conserve resources. While sarcoma demonstrated the greatest reduction in case volume, their case volume is relatively low compared to other specialties such as breast surgery and head and neck surgery. Conversely, the service with the lowest decrease in the number of cases was vascular surgery which represents in part the urgency of these operations, but also because placement of chemotherapy ports was necessary for patients to receive chemotherapy amidst the pandemic.

All operations were reviewed not only to determine which patients' surgeries were deemed life‐saving and nonelective, but also to ascertain which patients could be safely delayed without compromising their cancer care. Patients were evaluated in a multidisciplinary manner, taking into consideration patients' chemotherapy regimens and radiation as well their cancer stage and risk of progression. While some have proposed scoring systems that can provide objective guidance for whether a case should proceed amidst the pandemic, 14 our protocol allows discussion and consideration by one's peers to decipher whether or not an operation is considered urgent or emergent and warrants more expeditious surgery with input from the operating surgeon. Future studies will be necessary to determine whether the precautions and multidisciplinary review were successful in selectively rescheduling cases that were deemed elective. With the unpredictable behavior of Covid‐19, constant adjustments are necessary to ensure patients are treated appropriately without compromising their care, but also taking into account the availability of resources to ensure the highest degree of safety for other patients, faculty, and staff.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Covid‐19 has had a dramatic impact on all aspects of human life, particularly in terms of healthcare forcing medical professionals to make difficult decisions. However, when treating cancer, careful planning, exercising judicious precautions, and multidisciplinary strategies hopefully allow continued high‐level treatment without jeopardizing patients' care.

SYNOPSIS

The novel coronavirus has forced the world to make unheard of adjustments to the care of patients; however, for patients with cancer, many of the restrictions that were implemented can have a detrimental impact on cancer care. Despite federal and state mandates, surgical care was drastically reduced but was still provided for patients during the pandemic. Important changes in scheduling, allocation of resources, and an institutional wide effort were necessary to perform surgeries safely without jeopardizing staff, healthcare providers, and other patients.

Chang EI, Liu JJ. Flattening the curve in oncologic surgery: Impact of Covid‐19 on surgery at tertiary care cancer center. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:602–607. 10.1002/jso.26056

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, van Riel D, de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China—key questions for impact assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:692‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team . A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323:709. 10.1001/jama.2020.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199‐1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929‐936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cabrini L, Landoni G, Zangrillo A. Minimise nosocomial spread of 2019‐nCoV when treating acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2020;395:685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forrester JD, Nassar AK, Maggio PM, Hawn MT. Precautions for operating room team members during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1098‐1101. pii: S1072‐7515(20)30303‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prachand VN, Milner R, Angelos P, et al. Medically‐necessary, time‐sensitive procedures: a scoring system to ethically and efficiently manage resource scarcity and provider risk during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. pii: S1072‐7515(20)30317‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.