Sir,

We read with great interest the Special Editorial by Dr Thapa and co‐authors on the importance of not neglecting emotions of pregnant women during the COVID‐19 pandemic 1 as maternal mental health can be associated with short‐ and long‐term risks for their and their children’s physical and psychological health. Most studies on COVID‐19 in pregnancy have focused on physical effects of the pandemic on infected mothers as well as the possibility of vertical transmission: these tend to eclipse the equally relevant maternal mental health needs during these unprecedented times.

One of the practical difficulties that clinicians face is how objectively to measure mental health during pregnancy. In the UK, the Generalised Anxiety Score 7 (GAD‐7) 2 and Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) 3 are often used to screen for maternal anxiety and depression. It is unclear whether the pandemic has caused much depression in the pregnant population; however, Corbett and her colleagues from Dublin reported that pregnant women in general (without COVID‐19) have voiced heightened concerns about health of their family and unborn children as well as anxiety regarding compulsory behavioural changes such as social isolation, working remotely, transport difficulties, childcare and stockpiling (especially of food, hand sanitisers and toiletries). 4

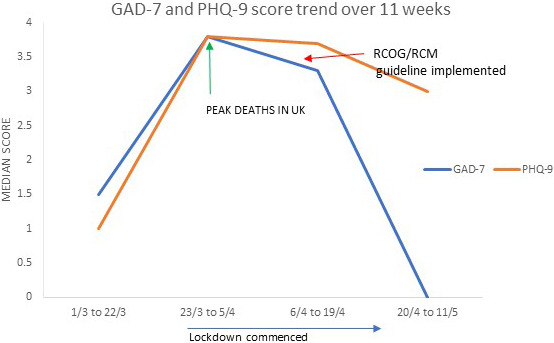

We recently published a small case series assessing maternal and fetal outcomes of the first COVID‐19 pregnancies in an inner city London hospital 5 and would like to share some pilot data on their anxiety and depression levels over the past 11 weeks of the pandemic. Eleven COVID‐19‐positive mothers completed the cross‐sectional survey, which were collected within 1 week of diagnosis by the first author (P.K.). The median age and gestation at delivery were 31 years (range 18‐39) and 39 weeks (range 27‐39), respectively. The median GAD‐7 score throughout the 11‐week period was 3 (scores of 5, 10 and 15 are taken as the cut‐off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety) and of note is the observation that median score rose to a maximum at the height of the pandemic deaths in the UK when “lockdown” rules were instituted amid great uncertainty about National Health Service capacity and COVID outcomes (Figure 1). The scores declined in the third quarter of the 11 weeks as more data from maternal cases were available, especially after Royal Colleges of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Midwifery jointly issued an informative guideline on management of COVID‐19 mothers and their babies on 17 April 2020. 6 The median PHQ‐9 score through the 11‐week period was 2 (scores of 5, 10, 15 and 20 represent boundaries for mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression) and followed a similar trajectory to that of GAD‐7 in the last few weeks of the lockdown.

Figure 1.

GAD‐7 (anxiety) and PHQ‐9 (depression) scores in COVID‐19 mothers over 11 weeks of the pandemic [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our pilot data suggest that maternal levels of anxiety at the tail end of the pandemic in the UK appear low, with depression levels following a similar pattern. This is likely to be due to increased available information and reassurance through social media, healthcare professionals and primary care. Nevertheless, despite these reassuring findings, we agree with Dr Thapa and colleagues that maternal mental health should not be overlooked at the expense of the more obvious physical effects of COVID‐19 illness during this period.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thapa SB, Mainali A, Schwank SE, Acharya G. Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:817‐818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalised anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092‐1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Hehir MP, Lindow SW, O'Connell MP. Health anxiety and behavioural changes of pregnant women during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;249:96‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Govind A, Essien S, Kartikeyan A, et al. Re: Novel Coronavirus COVID‐19 in late pregnancy: Outcomes of first nine cases in an inner city London hospital. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;S0301–2115(20)30257–8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.05.004. Online ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royal College of Midwives . Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Corona Virus Infection in Pregnancy. Information for healthcare professionals. V8 17/4/2020. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020‐04‐17‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐infection‐in‐pregnancy.pdf