Abstract

Clinical decision-making in kidney transplant (KT) during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is understandably a conundrum: both candidates and recipients may face increased acquisition risks and case fatality rates (CFRs). Given our poor understanding of these risks, many centers have paused or reduced KT activity, yet data to inform such decisions are lacking. To quantify the benefit/harm of KT in this context, we conducted a simulation study of immediate-KT vs delay-until-after-pandemic for different patient phenotypes under a variety of potential COVID-19 scenarios. A calculator was implemented (http://www.transplantmodels.com/covid_sim), and machine learning approaches were used to evaluate the important aspects of our modeling. Characteristics of the pandemic (acquisition risk, CFR) and length of delay (length of pandemic, waitlist priority when modeling deceased donor KT) had greatest influence on benefit/harm. In most scenarios of COVID-19 dynamics and patient characteristics, immediate KT provided survival benefit; KT only began showing evidence of harm in scenarios where CFRs were substantially higher for KT recipients (eg, ≥50% fatality) than for waitlist registrants. Our simulations suggest that KT could be beneficial in many centers if local resources allow, and our calculator can help identify patients who would benefit most. Furthermore, as the pandemic evolves, our calculator can update these predictions.

KEYWORDS: clinical research/practice, infection and infectious agents, kidney transplantation/nephrology, Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients (SRTR)

Abbreviations: CART, classification and regression tree; CFR, case fatality rate; KT, kidney transplant; LMG5, life-months gained over the first 5 years; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; SS-DMF, Social Security Death Master File

1. INTRODUCTION

The first case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was reported on January 20, 2020.1 Since then, there has been widespread nationwide transmission of SARS-CoV-2, with >550 000 cases and 20 000 deaths in the United States as of April 12, 2020.2 Case fatality rates (CFRs), ranging from 0.06% to 13.4%,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 remain poorly quantified, but seem highest among the elderly, comorbid, and immunocompromised.4 , 8, 9, 10 This introduces major considerations and uncertainty for both kidney transplant (KT) candidates and recipients during the pandemic.8 , 11 , 12 As such, most centers across the country have either paused or reduced both living donor (LDKT) and deceased donor (DDKT) activity. While centers in areas with the highest COVID-19 incidence have tended to be more restrictive in KT practice, many centers in areas with lower COVID-19 incidence have also followed suit.13

Decision-making in the setting of this pandemic is understandably a conundrum. Transplanting a patient puts them at risk of COVID-19 during a time of high immunosuppression, with potentially higher fatality from the disease. On the other hand, leaving a patient on dialysis puts them at risk of the usual dialysis mortality. Moreover, both waitlist patients and transplant recipients may have unique risks of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition; in particular, some dialysis recipients may face additional risk due to the need to obtain dialysis, while some transplant recipients may face additional risk due to nosocomial transmission at the time of surgery or immunosuppression posttransplant. Furthermore, a patient who is 3 years from the top of the waiting list might experience an extra benefit by receiving a transplant at a riskier time, such as this pandemic, which might offset the risk of waiting 3 more years once the pandemic has settled, whenever that might occur.

Making decision-making even more difficult is the rapidly evolving landscape of COVID-19 transmission, detection, disease course, and treatment as we learn about the disease in real-time and as the pandemic shifts. With no evidence-based algorithms to guide practice, transplant centers are left to independently assess and mitigate risk on their own for their vulnerable patient population. In the face of a rapidly changing epidemic, observational data cannot provide information about long-term implications of decisions being made in real-time. However, a simulation capable of accounting for varying patient and disease parameters can inform understanding of the effect of a delay in KT on patient survival.

To address this need, we built a flexible simulation to model waitlist and post-KT mortality in the United States in the context of COVID-19, under a variety of hypothetical scenarios. The advantages of our flexible simulation are the following: (1) it can consider patient characteristics including priority on the waiting list; (2) it can consider aspects of the pandemic specific to the geographic location of the transplant center making the decision; and (3) it allows a wide range of inputs (including acquisition risks and CFRs specific to candidates and recipients) that can evolve as we learn more about the disease, or as the geographic landscape of the disease changes. Our findings can help to inform decision-making for transplant providers and patients during these uncertain times.

2. METHODS

2.1. DATA source

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere.14 The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. The SRTR data system includes a linkage to the Social Security Death Master File (SS-DMF) for mortality ascertainment.

2.2. Waitlist mortality in the absence of COVID-19

To model waitlist mortality in the absence of COVID-19, we studied 300 441 adult and pediatric kidney waitlist registrants prevalently listed any time between January 1, 2013 and June 30, 2019 using SRTR data. Non-US residents (N = 3513) were excluded due to potentially unreliable mortality ascertainment using SS-DMF data. Individuals were followed from the later of first active listing date or January 1, 2013 until death, waitlist removal, or administrative censorship on June 30, 2019. Removal from the waitlist due to deteriorating condition was treated as equivalent to mortality. Waitlist mortality was modeled using Poisson regression, as a function of age at listing (categorized as 0-11, 12-17, 18-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, or ≥70); history of prior transplant; history of diabetes; time on dialysis at listing (categorized as non/preemptive, <1, 1-3, 3-5, or >5 years); race/ethnicity (categorized as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, or other); sex (categorized as male or female); and primary payer (categorized as private, Medicaid, Medicare, other public insurance, or all others). This model was used to calculate patient-specific probability of waitlist mortality per month. We used these models and the model of waitlist mortality to calculate overall predicted waitlist and posttransplant mortality in the absence of COVID-19, to illustrate predicted risk as used for input into the Markov model.

2.3. Posttransplant mortality in the absence of COVID-19

To model posttransplant mortality in the absence of COVID-19, we studied 121,641 adult and pediatric living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) and deceased-donor kidney transplant (DDKT) recipients between January 1, 2013 and June 30, 2019 using SRTR data. Non-US residents (N = 1624) were excluded as explained above. Individuals were followed from date of transplant to death or administrative censorship on June 30, 2019. Separately for LDKT and DDKT recipients, posttransplant mortality was modeled using Poisson regression, as a function of time since transplant (categorized as 0-30, 31-91, 91-182, 182-365 days, 1-3, or 3-5 years) and age at listing, history of prior transplant, history of diabetes, time on dialysis at listing, race/ethnicity, and primary payer (all categorized as above). These models were used to calculate patient-specific probability of posttransplant mortality per month.

2.4. Parameters of the COVID-19 pandemic

Potential parameters that might affect the survival benefit of immediate transplant vs delayed transplant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic include the expected length of delay (if transplant is postponed), community risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition over time, additional risk in waitlist candidates receiving in-center dialysis, nosocomial risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition at transplant (from the donor or from the hospitalization); and the CFRs of SARS-CoV-2 among waitlist registrants and transplant recipients. We tested multiple values for these parameters in the simulation ( Table 1). In particular, the length of delay could range from 0 to 60 months. We selected 9 different scenarios of community SARS-CoV-2 acquisition risk, from “1” to “high-sustained” (10% risk per month over the first 12 months, and 3% per month thereafter). We selected 3 options for additional acquisition risk for waitlist registrants: none above community risk, 1.5× community risk, or 2× community risk. We selected 3 options for nosocomial risk at transplant: none, 10% added to community risk, or 20% added to community risk. We selected 5 options for waitlist CFRs, ranging from “low” (comparable to age-specific case fatality rates observed in Wuhan, China)15 to “lethal” (100%), and the same 5 options for posttransplant CFRs.

TABLE 1.

COVID-19 epidemic parameters in the simulation model. All 20 250 permutations of these parameters were modeled

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Community CoV acquisition risk |

|

| Additional risk on waitlist | None, 1.5× community risk, or 2× community risk |

| Nosocomial risk at transplant | None, 10% added to community risk (eg, 1% to >11%), or 20% added to community risk. If community risk is zero, nosocomial risk at transplant is also zero |

| Delay of transplant | 3, 6, 12, 24 mo, or never |

| Case fatality rates (waitlist) |

|

| Case fatality rates (posttransplant). COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019 | Same values as case fatality rates (waitlist) |

2.5. Simulation of outcomes in the context of COVID-19

To quantify the survival benefit or harm of immediate KT vs delay in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic, we simulated immediate-transplant and delayed-transplant outcomes using a Markov decision process model and probabilities from the models described above, for each unique patient phenotype that occurred in the 2019 prevalent waitlist population ( Figure 1). The simulation was run with a 5-year time horizon and 1-month step time. Designate survival at month m after transplant as STm (with ST0 = 1), survival at month m after delay as SDm (with SD0 = 1), probability of waitlist mortality at month m (in absence of COVID-19) as Wm, probability of posttransplant mortality in absence of COVID-19 at month m posttransplant as Tm, community probability of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition as Cm, additional risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition for waitlist registrants as Cw, nosocomial risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition through transplantation as Ct, the CFR among waitlist registrants as CFRw, and the CFR among transplant recipients as CFRt. We calculated

FIGURE 1.

State diagram of the Markov model. Patients who select “delay” and survive through n months after the delay transition from a “Waitlist” state to a "KT" state. Other state transition probabilities are determined by Markov model parameters and/or Poisson models of waitlist and post-KT mortality. CoV, coronavirus 2; KT, kidney transplant [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

when m exceeded the delay of transplant d, we calculated SDm based on posttransplant mortality Tm−d instead of waitlist mortality Wm. Using SD and ST, separately for each combination of patient covariates and COVID-19 epidemic parameters we calculated life-months gained due to transplantation over the first 5 years (LMG5). LMG5 in principle can vary from −60 to 60; a positive value indicates survival benefit from immediate KT while a negative value indicates harm.

2.6. Determining parameters that drive benefit or harm of KT

To characterize the clinical and epidemic scenarios where immediate KT would confer benefit vs harm, we quantified the association of the simulation parameters with the estimated survival benefit, as measured in LMG5, using 2 machine learning algorithms. First, to produce a high-level, human-readable summary of model output, we created a decision tree using the classification and regression trees (CART).16 Briefly, CART splits the study population into 2 subgroups at a threshold value of a predictor. The threshold value and the predictor are selected such that the difference in LMG5 between the 2 subgroups would be maximized. This process is continued recursively, creating a decision tree, until a predefined stopping rule is met. The decision tree illustrates what clinical or epidemical factor drives benefit or harm of KT in an intuitive way.

In addition, to identify the relative importance of different patient characteristics and epidemic parameters in determining benefit/harm of KT, we used random forests.17 In random forests, multiple independent decision trees (ie, a "forest") are created, with each tree using a random bootstrap-resample of the dataset and on a random subset of the predictor variables. Each variable’s importance is evaluated by randomly permuting the values of the variable (hence rendering the variable uninformative) and evaluating the decrease in predictive performance compared to that from the original dataset. Variable importance is presented in relative terms since its scale is irrelevant.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Confidence intervals are presented as per the method of Louis and Zeger.18 Waitlist and posttransplant mortality models and the simulation were constructed using Stata/MP 16.1 (College Station, TX). CART and random forests analyses were performed using rpart (Minneapolis, MN; v.4.1-15) and ranger (Berlin, Germany; v.0.12.1) on R (v.3.6.3).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Waitlist mortality in the absence of COVID-19

Waitlist mortality for a reference waitlist patient (age 50-59, not on dialysis, no history of diabetes or prior transplant, white, private insurance, male) in the absence of COVID-19 was 0.37% per month or 4.4% per year ( Table 2). Older age, time on dialysis, history of diabetes, prior transplant, and public insurance were associated with greater risk (all P < .001, Table 2). Nonwhite race/ethnicity was associated with decreased risk after adjusting for other candidate characteristics (all P < .01, Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Waitlist mortality in absence of COVID-19

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio |

|---|---|

| Baseline mortality risk per person-mo | 0.360.370.38% |

| Age (y) | |

| 0-11 | 0.340.450.60 |

| 12-19 | 0.160.230.32 |

| 20-29 | 0.350.380.40 |

| 30-39 | 0.470.490.52 |

| 40-49 | 0.660.680.70 |

| 50-59 | Reference |

| 60-69 | 1.471.501.53 |

| 70+ | 2.192.262.33 |

| Dialysis time | |

| None | Reference |

| <1 y | 1.221.261.30 |

| 1-2 y | 1.481.531.57 |

| 3-4 y | 1.962.022.09 |

| 5+ y | 2.652.742.82 |

| History of diabetes | 1.741.771.80 |

| Prior transplant | 1.281.321.35 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | Reference |

| Asian | 0.590.620.64 |

| Black | 0.710.720.74 |

| Hispanic | 0.670.690.71 |

| Other | 0.710.760.81 |

| Payor | |

| Private | Reference |

| Medicare | 1.181.231.28 |

| Medicaid | 1.111.131.16 |

| Other public | 1.121.191.27 |

| Other | 1.041.141.25 |

| Sex: female | 0.980.991.01 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019.

3.2. Posttransplant mortality in the absence of COVID-19

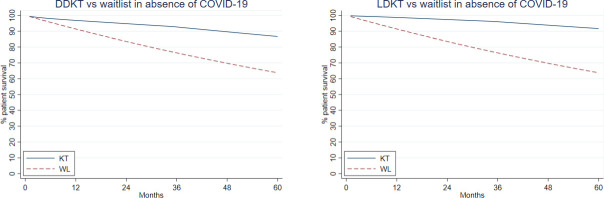

For a reference patient, mortality risk in the 30 days posttransplant was 0.11% (LDKT)/0.41% (DDKT) and declined in subsequent months ( Table 3). Older age, longer time on dialysis, history of diabetes, and prior transplant were all associated with greater post-LDKT and post-DDKT mortality risk (all P < .01) (Table 3). Medicare and Medicaid as primary payer were associated with greater post-KT mortality risk (all P < .02) (Table 3). Nonwhite race/ethnicity was associated with decreased risk after adjusting for other candidate characteristics (Table 3). Overall predicted mortality in absence of COVID-19, based on the waitlist and post-DDKT/post-LDKT models, appears in Figure 2.

TABLE 3.

Posttransplant mortality in absence of COVID-19

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio (LDKT) | Hazard ratio (DDKT) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality risk per mo | ||

| 0-30 d post-KT | 0.080.110.14% | 0.360.410.47% |

| 31-90 d post-KT | 0.030.040.05% | 0.190.210.24% |

| 91-182 d post-KT | 0.020.030.04% | 0.140.160.18% |

| 183-365 d post-KT | 0.030.040.05% | 0.110.130.14% |

| 1-3 y post-KT | 0.040.040.05% | 0.100.110.13% |

| 3-5 y post-KT | 0.060.070.09% | 0.160.180.20% |

| Age (y) | ||

| 0-11 | 0.210.390.73 | 0.290.410.59 |

| 12-19 | 0.160.340.71 | 0.140.210.32 |

| 20-29 | 0.230.320.45 | 0.240.290.36 |

| 30-39 | 0.450.570.71 | 0.350.400.46 |

| 40-49 | 0.450.540.65 | 0.590.640.70 |

| 50-59 | Reference | Reference |

| 60-69 | 1.551.772.03 | 1.531.621.72 |

| 70+ | 2.002.402.87 | 2.212.382.57 |

| Dialysis time | ||

| None | Reference | Reference |

| <1 y | 1.221.421.65 | 1.071.191.32 |

| 1-2 y | 1.431.651.91 | 0.971.061.17 |

| 3-4 y | 1.672.032.47 | 1.111.221.33 |

| 5+ y | 2.182.733.42 | 1.381.511.65 |

| History of diabetes | 1.781.992.22 | 1.641.721.80 |

| Prior transplant | 1.371.581.82 | 1.181.271.36 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Asian | 0.270.380.53 | 0.530.590.66 |

| Black | 0.700.830.97 | 0.780.830.88 |

| Hispanic | 0.420.510.61 | 0.590.640.69 |

| Other | 0.570.891.41 | 0.710.830.98 |

| Payor | ||

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Medicare | 1.091.512.08 | 1.101.251.42 |

| Medicaid | 1.221.381.56 | 1.131.211.29 |

| Other public | 0.340.821.98 | 0.650.811.01 |

| Other | 0.450.911.84 | 0.590.831.18 |

| Sex: female | 0.860.961.07 | 0.810.850.90 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019.

FIGURE 2.

Overall predicted waitlist and post-DDKT/post-LDKT mortality in absence of COVID-19, based on Poisson regressions used for input to the Markov model. COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplant; LDKT, living donor kidney transplant [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3. Outcomes in the context of COVID-19

Across all patient phenotypes and simulation parameters, LMG5 ranged from −48.4 (KT exceptionally harmful) to 55.0 (KT exceptionally beneficial), with median (interquartile range) of 3.8 (0.1-13.4). LMG5 exceeded 0 (at least some benefit from KT) in 72.1% of simulations, including 97.4% of simulations in which the COVID-19 CFR for KT recipients was less than or equal to the CFR for waitlist registrants, and 34.2% of simulations in which the COVID-19 CFR for KT recipients was greater than the CFR for waitlist registrants. Representative immediate-KT and delayed-KT survival curves appear in Figure 3; changing a single parameter may be sufficient to change inference from the model. Survival benefit of immediate KT was greater when the COVID-19 CFR was increased in waitlist registrants ( Figure 4A), and less when the COVID-19 CFR was increased in transplant recipients (Figure 4B). Increasing the community risk of COVID-19 acquisition increased the variance in survival benefit (Figure 4C). Changing the additional risk of COVID-19 for dialysis patients had relatively little effect on survival benefit (Figure 4D). The survival benefit was greater when the length of delay was increased; that is, the longer a patient would wait (due to factors such as program closure, lack of hospital resources, or in the case of DDKT, likely additional wait for another suitable organ offer), the more benefit of immediate KT (Figure 4E). The survival benefit was slightly higher for older patients (Figure 4F).

FIGURE 3.

Examples of simulated survival curves for immediate DDKT vs delay. A, White male patient, private insurance, age 20-29, 1-2 y on dialysis, no DM, no prior KT. Community COVID-19 acquisition risk is “medium-lingering,” acquisition risk is 50% higher for dialysis patients, and probability of nosocomial acquisition at KT is 10%; “medium” waitlist and post-KT CFR; 6-mo delay. A, “Medium” waitlist and post-KT CFR, 6-mo delay. B, Like (A) except 24-mo delay. C, Like (A) except “high” waitlist CFR. D, Like (A) except “very high” post-KT CFR. E, Like (A) except community COVID-19 acquisition risk is “high-lingering.” F, Like (A) except age 70+. CFR, case fatality rate; COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplant; DM, diabetes mellitus; KT, kidney transplant [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of life-months gained over 5 years from immediate vs delayed KT: effect of varying a single parameter. All distributions are for a white male patient with private insurance and no prior KT. CoV, coronavirus 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; KT, kidney transplant [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. Determining parameters that drive benefit or harm of KT

Our CART analysis suggested that immediate KT continues to provide survival benefit in most cases ( Figure 5). KT provides the greatest survival benefit when the waitlist CFR is “lethal”; community COVID-19 acquisition risk is “medium” or “high”; the delay would last 24 months or more; and the post-KT CFR is “low,” “medium,” or “high” (LMG = 30.1) (CFR/COVID-19 risk parameters in Table 1). On the other hand, KT will result in harm only when CFRs are substantially higher for KT recipients (eg, 50% or greater) than for waitlist registrants (eg, 30% or lower), and community risk of COVID-19 acquisition is “medium” or “high.” In this case, KT will reduce life-months, either by 5.3 or 12.3 over the 5 years after KT, depending on the CFR for KT recipients. Similar to our findings from the CART decision tree, our random forests analysis showed that waitlist CFR, post-KT CFR, community COVID-19 risk, and length of delay had substantially larger variable importance compared to all other variables, which had only minimal importance ( Table 4).

FIGURE 5.

CART summarizing estimated LMG5 from immediate transplant vs delay, based on epidemic characteristics and length of delay. Details of CFRs and COVID-19 risk parameters appear in Table 1. CART, classification and regression tree; CFRs, case fatality rates; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; KT, kidney transplant; LMG5, life-months gained over the first 5 years

TABLE 4.

Variable importance of the simulation parameters estimated via random forests

| Parameter | Variable importance |

|---|---|

| Waitlist COVID-19 CFR | 1 (Reference) |

| Post-KT COVID-19 CFR | 0.933 |

| Community COVID-19 risk | 0.529 |

| Length of delay | 0.309 |

| Additional COVID-19 risk on waitlist | 0.087 |

| Age | 0.086 |

| Time on dialysis | 0.033 |

| Nosocomial COVID-19 risk at KT | 0.024 |

| History of diabetes | 0.017 |

| LDKT vs DDKT | 0.003 |

| History of prior transplant | 0.002 |

| Race/ethnicity: Asian | 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity: black | 0.001 |

| Insurance type | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity: Hispanic | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity: other nonwhite | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CFR, case fatality rate; COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplant; KT, kidney transplant; LDKT, living donor kidney transplant.

4. DISCUSSION

In this simulation based on national data and a variety of scenarios of COVID-19 including differences in incidence of the disease, KT provided survival benefit in most simulated scenarios with the exception of those in which the CFR of COVID-19 in KT recipients substantially exceeded the CFR for waitlist candidates. Even many scenarios of LDKT during the pandemic proved beneficial. Individual risk/benefit estimations for patients of different phenotypes in geographies with different COVID-19 incidence can be obtained using our risk calculator at http://www.transplantmodels.com/covid_sim. Furthermore, as the pandemic evolves in the United States, new estimates can be obtained by varying these parameters in our calculator.

Key parameters of our model include community SARS-CoV-2 acquisition risk, additional risk to waitlist registrants, nosocomial risk at time of KT, and CFRs. The true values of these parameters will vary substantially over time and place. Unfortunately, in the absence of adequate community testing and testing of waitlist and transplant populations in particular, these parameters will remain unknown. Research is urgently needed to quantify COVID 19–related risk in transplant populations. However, our models suggest that under a wide range of assumptions, KT continues to provide survival benefit unless CFRs for transplant recipients are unrealistically high (generally, above 50%). Moreover, as new research emerges, the flexibility of our model allows researchers to select parameter values accordingly.

Our model estimates benefit or harm of LDKT and DDKT to KT candidates in the context of COVID-19. Under most scenarios, we demonstrate substantial benefit to the recipient following LDKT. Our model does not account for risk to living kidney donors, who may also be at increased risk due to COVID-19. Providers and patients should carefully consider the potential risks, while acknowledging that living organ donors already voluntarily accept increased risk in hopes of providing a benefit to the transplant recipients.

Our study must be understood in the context of its limitations. A simulation study relies on accurate inputs for accurate inference. We developed our waitlist and posttransplant mortality models using national registry data, and overall event rates and risk factors are consistent with numerous prior reports.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Nevertheless, any estimation error from these models will influence our inferences. It is also possible that hospitals overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients will be less able to evaluate and treat post-KT complications; while we could not model this directly, parameters in our calculator can be varied to account for potentially increased mortality resulting from this secondary effect. Similarly, while we did not directly model nuances such as how well the recipient has been practicing social distancing, these can also be accounted for by varying parameters in our calculator.

Finally, our model strongly depends on parameters of the COVID-19 pandemic about which very little is currently known: CFRs of COVID-19 acquisition in waitlist registrants and KT recipients, and future risk of COVID-19 transmission. Our ability to quantify these will no doubt evolve, particularly as testing becomes more widespread. To address this, we developed our model to accommodate a wide variety of possible scenarios, and we will continue to update the online calculator if future research indicates scenarios beyond the range that we considered. Nevertheless, the fact that in our simulations KT quite reliably provides survival benefit except in the case of fairly drastic assumptions (generally, 50% or higher mortality risk for KT recipients exposed to COVID-19, which is much higher than has been described in current case series) suggests that closure of transplant programs in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic comes at a cost to KT waitlist registrants, and such drastic action may not be necessary.

It is critically important to note that, while this simulation study provides real-time assessment of the risk-benefit profile for specific KT candidates at centers with specific COVID-19 risk, it cannot account for local resource availability. In some areas, there is significant concern regarding the availability of hospital beds, ventilators, blood, personal protective equipment, and a healthy workforce.24, 25, 26, 27 The results of our simulation must be taken in the context of local resources when determining center-specific courses of action. Even in scenarios where KT provides substantial survival benefit, cessation of transplantation may be unavoidable to preserve resources and workforce. In that setting, our study helps to quantify the effect of delay on KT candidate survival. The landscape of COVID-19 is evolving rapidly and it is impossible to forecast what the risk-benefit profile will be in the next weeks to months. For that reason, we designed our simulation to be flexible and modifiable.

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic introduces uncertain risks to transplant candidates and recipients; however, simulation suggests that even after weighing the potential risks of COVID-19 infection, KT still provides survival benefit to transplant candidates in most scenarios. If local resources allow, it might be reasonable to continue KT unless evidence emerges of extremely high CFRs of COVID-19 among recipients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant number K01KD101677 (Massie), K23DK115908 (Garonzik-Wang), and K24DK101828 (Segev) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (HHRI) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the US Government.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

Funding information National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: K01DK101677, K23DK115908 and K24DK101828

REFERENCES

- 1.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burki T. Outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(3):292–293. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizumoto K, Chowell G. Estimating risk for death from 2019 novel coronavirus disease, China, January-February 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1251–1256. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T, Jung S-M, Linton NM, et al. Communicating the risk of death from novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):580. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung S-M, Akhmetzhanov AR, Hayashi K, et al. Real-time estimation of the risk of death from novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: inference using exported cases. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):523. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DH, Choe YJ, Jeong JY. Understanding and interpretation of case fatality rate of coronavirus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(12):e137. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishman JA, Grossi PA. Novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) in the immunocompromised transplant recipient: #Flatteningthecurve. Am J Transplant. 2020. [Published online ahead of print]. 10.1111/ajt.15890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandolfini I, Delsante M, Fiaccadori E, et al. COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020. 10.1111/ajt.15891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kumar D, Manuel O, Natori Y, et al. COVID-19: a global transplant perspective on successfully navigating a pandemic. Am J Transplant. 2020. [Published online ahead of print]. 10.1111/ajt.15876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Boyarsky BJ, Po-Yu Chiang T, Werbel WA, et al. Early impact of COVID-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2020. [Published online ahead of print]. 10.1111/ajt.15915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Segev DL. Big data in organ transplantation: registries and administrative claims. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1723–1730. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JT, Leung K, Bushman M, et al. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat Med. 2020;26:506–510. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1984. Classification and regression trees. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals. Biostatistics. 2009;10(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, et al. Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA. 2011;306(6):620–626. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. SRTR program specific reports. https://www.srtr.org/about-the-data/technical-methods-for-the-program-specific-reports/. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- 21.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(Suppl S1):20–130. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelton BA, Sawinski D, Mehta S, Reed RD, MacLennan PA, Locke JE. Kidney transplantation and waitlist mortality rates among candidates registered as willing to accept a hepatitis C infected kidney. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(2):e12829. doi: 10.1111/tid.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawinski D, Forde KA, Lo Re V, et al. Mortality and kidney transplantation outcomes among hepatitis C virus-seropositive maintenance dialysis patients: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(6):815–826. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgner A, Ikizler TA, Dwyer JP. COVID-19 and the inpatient dialysis unit: managing resources during contingency planning pre-crisis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(5):720–722. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03750320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell R, Banks C, Authoring Working Party Emergency departments and the COVID-19 pandemic: making the most of limited resources. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(5):258–259. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Yao W, Wang Y, Long C, Fu X. Wuhan and Hubei COVID-19 mortality analysis reveals the critical role of timely supply of medical resources. J Infect. 2020;81(1):147–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.