1.

The new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection, has become a pandemic. Here, we report a patient with Guillain‐Barré syndrome (GBS) who had evidence of a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection, but was otherwise asymptomatic for COVID‐19 except for a low‐grade fever.

A 53‐year‐old previously healthy woman presented with a 3‐day history of dysarthria associated with progressive weakness and numbness of the lower extremities. She had no history of recent infection or vaccination. Vital signs were normal. A neurologic examination revealed mild dysarthria due to jaw weakness and bilateral, predominantly lower limb weakness, with 4−/5 strength in knee and ankle flexor and extensor muscles, and 4−/5 in the left and 4+/5 in right hip flexor muscles by the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. She could walk only with assistance. There was slight weakness in her hand muscles. Reduced sensation to pinprick was found distally to the upper thighs. Tendon reflexes were absent in the lower extremities. GBS was considered to be the most likely diagnosis.

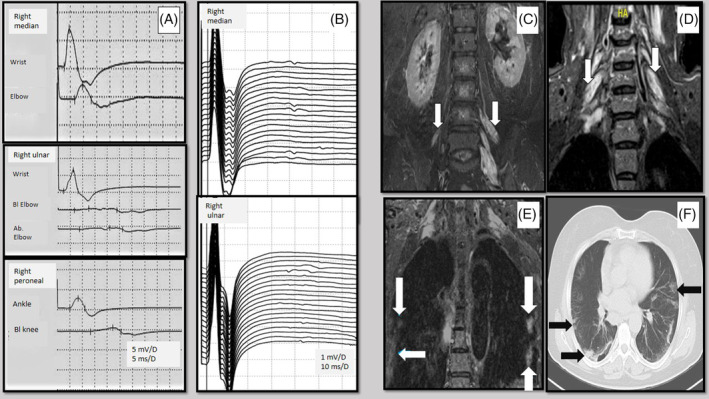

Biochemical screening (electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, C‐reactive protein) and HIV test were normal other than mild neutropenia (1.49 cells/μL) and a high monocyte percentage (19.77; normal 4–12) in the complete blood count. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) confirmed a demyelinating pattern with conduction blocks and temporal dispersion in motor nerves (Figure 1A, Table 1). Ulnar and median nerves demonstrated normal minimal F‐wave latencies with decreased persistence (median 55%; ulnar 65%) and increased chronodispersion (median 22.1 ms; ulnar 18.0 ms) (Table 1; Figure 1B). Plasma exchange (five sessions; one every other day) was performed 5 days after the onset of neurologic symptoms.

FIGURE 1.

Electrodiagnostic and radiologic findings of the patient. (A) Motor nerve conduction studies showing conduction blocks and temporal dispersion. (B) F‐waves recorded from abductor pollicis brevis and abductor digiti minimi muscles. (C) Coronal STIR image from lumbar spine MRI, asymmetric thickened and hyperintense nerve roots of lumbar plexus (arrows). (D) Coronal STIR image from cervical spine MRI, thickened and hyperintense nerve roots of the brachial plexus (arrows). (E) Coronal STIR image from brachial plexus MRI, focal intensities in peripheral areas of the lungs (arrows). (F) Axial chest CT image, bilateral peripheral ground‐glass and consolidative pulmonary opacities (arrows)

TABLE 1.

Nerve conduction studies of the patient

| Motor Nerve Conduction Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Latency | Amplitude | CV | F Latency |

| ms | mV | m/s | ms | |

| Right Median | ||||

| Wrist | 2.8 (<4) | 6.6 (>5) | 26.6 | |

| Elbow | 6.7 | 2.5 | 55.8 (>50) | |

| Right Ulnar | ||||

| Wrist | 2.7 (<3.4) | 6.1 (>5) | 29.2 | |

| Bl. elbow | 7.1 | 0.5 | 49.2 (>50) | |

| Ab. elbow | 9.8 | 0.5 | 40.8 (>50) | |

| Right Peroneal | ||||

| Ankle | 4.5 (<5) | 2.5 (>2) | ||

| Bl. knee | 13.3 | 1 | 38.4 (>40) | |

| Right Tibial | ||||

| Ankle | 5.7 (<6) | 3.1 (>4) | 43.6 | |

| Knee | 13.1 | 2.6 | 47.3 (>40) | |

| Sensory Nerve Conduction Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Peak Latency | Amplitude | CV | |

| ms | uV | m/s | ||

| Right Median | 2.4 (<2.8) | 22.4 (>12) | 63.3 (>50) | |

| Right Ulnar | 1.6 (<2.5) | 15.8 (>10) | 73.2 (>50) | |

| Right Sural | 2.8 (<3.8) | 21.4 (>10) | 73.7 (>40) | |

Ab:Above; Bl: Below; CV: conduction velocity.

Normal values are in parentheses.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar and cervical spines revealed asymmetrical thickening and hyperintensity of postganglionic roots supplying the brachial and lumbar plexuses in short‐tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences (Figure 1C,D). Focal intensities suspicious for COVID‐19 pneumonia were incidentally identified in peripheral areas of lungs on STIR sequence of the brachial plexus MRI (Figure 1E). She had a mild fever (37.5°C) but no cough, dyspnea, anosmia, or ageusia. Chest computed tomography showed bilateral peripheral ground‐glass opacities and consolidations on both lungs (Figure 1F); the patient was placed in isolation. She had mild lymphopenia (1.042/mm3) and high C‐reactive protein level (33.2 mg/L; normal 0–5 mg/L). Nasopharyngeal swab for real‐time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) SARS‐CoV‐2 was positive. She was treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis on day 7 of admission showed a protein level of 32.6 mg/dL with no leucocytes and a CSF test for SARS‐CoV‐2 was negative. Two weeks after the onset of symptoms, the neurologic findings had improved markedly; MRC scores were 4+/5 in lower limb muscle groups, and she was able to walk without assistance.

Neurologic manifestations during the course of COVID‐19 infection have been described. 1 Previous reports of GBS and COVID‐19 demonstrated marked respiratory symptoms before or concurrent with the onset of neurologic symptoms. 2 , 3 , 4 In contrast, our patient with GBS had evidence of a COVID‐19 infection, but was otherwise asymptomatic for COVID‐19 except for a low‐grade fever.

We speculate that the pathophysiologic mechanism of GBS in COVID‐19 may be para‐infectious rather post‐infectious, likely due to “molecular mimicry” that preferentially affects the nervous system before the respiratory system. Another explanation could be direct viral neuropathogenic effects on the nervous system. 5

This possibility that this patient acquired the virus nosocomially cannot be ruled out, because we did not perform microbiologic testing at the time of admission. In the neurology clinic, during the hospitalization period, none of the other patients or staff had symptoms, and none of the contacts had positive PCR results for SARS‐CoV‐2. The initial laboratory test demonstrating a high monocyte percentage might also support an infection before hospital admission. 6

The diagnosis of acute‐onset chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) cannot be excluded. Nearly 16% of patients with CIDP show an acute onset, and plasma exchange might have prevented progression. Motor weakness with less prominent sensory signs at presentation support the diagnosis of GBS. 7

In conclusion, our findings highlight the importance of attention to the subtle clinical findings of COVID‐19 infection in newly diagnosed GBS.

Abbreviations

- CIDP

chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- GBS

Guillain‐Barré syndrome

- MRC

Medical Research Council

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NCS

nerve conduction studies

- RT‐PCR

real‐time polymerase chain reaction

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- STIR

short‐tau inversion recovery

2. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL PUBLICATION STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, et al. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. JAMA Neurol. 2020;2020:1127. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2574‐2576. 10.1056/NEJMc2009191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Virani A, Rabold E, Hanson T, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. IDCases. 2020;20:e00771. 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain‐Barré syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):383‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hadden RD, Karch H, Hartung HP, et al. Preceding infections, immune factors, and outcome in Guillain‐Barré syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56(6):758‐765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jin Y‐H, Cai L, Cheng Z‐S, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dionne A, Nicolle MW, Hahn AF. Clinical and electrophysiological parameters distinguishing acute‐onset chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy from acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(2):202‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]