Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic poses unprecedented challenges to public health care systems and demands intergovernmental coordination to cope with the resulting medical surge. This essay analyzes the operation of Paired Assistance Programs (PAPs) in China, offering a timely comparative case for researchers and practitioners to examine when reflecting on the classic debate over the hierarchical versus network approaches to coordination in emergency management. PAPs highlight the importance of network management and necessity of institutionalizing mechanisms of governance to facilitate coordination within multilevel response systems.

The combined effects of the COVID‐19 outbreak—its historic scale, uncertain epidemiology, and exponential transmission speed—have posed severe and unprecedented challenges to public health care systems around the globe. Health care delivery systems have been overwhelmed by mounting shortages of medical professionals and supplies. With the substantial influx of patients into hospitals, governments need to increase surge capacity by assessing the scope of the crisis, mobilizing personnel, and matching resources to the scale of the emergency (Ansell, Boin, and Keller 2010).

As a result of the outbreak of COVID‐19, China faced a medical surge in Hubei Province, the traffic hub of nine neighboring provinces in central China. In January, its capital city, Wuhan, became the epicenter of the virus in China, and a mandatory lockdown was issued on January 23, 2020 (Xinhua News Agency 2020d). Wuhan's medical capacity is above average among cities at the same administrative level (Wuhan Health Commission 2019). However, demand for medical personnel and hospital beds increased dramatically, paralyzing the medical system within a few days. Most cities in Hubei Province did not have the capacity to provide medical treatment to the rapidly growing number of patients. Therefore, China's central government implemented a series of Paired Assistance Programs (PAPs), calling for assistance from other provinces and cities. Cities 1 in Hubei Province received help from 19 provinces, gradually slowing the spread of COVID‐19 by late February (Xinhua News Agency 2020d).

The primary question explored in this article is, how did PAPs in China function to increase medical surge capacity in response to COVID‐19? The initiation, function, and management of PAPs touches on a key coordination issue in emergency management. Their operation during the COVID‐19 crisis offers a comparative case for researchers and practitioners to examine when reflecting on the classic debate regarding a hierarchical versus a network approach to emergency management. This example of PAP implementation by a centralized government system offers timely support for applying both hierarchical and network structures of coordination in response to COVID‐19. Furthermore, administration of these PAPs offers support for institutionalizing or strengthening mechanisms of governance to facilitate coordination for multilevel crisis response, topics that have crucial implications for improving emergency management.

Crisis Coordination in Multilevel Response Systems

The COVID‐19 pandemic has crossed political, jurisdictional, and national boundaries. Responding to such a transboundary crisis requires the engagement of government agencies at all levels, as well as a wide range of organizations from the nonprofit and private sectors. This section briefly reviews the literature discussing modes of coordination and governance structures.

Hybrid Modes of Coordination

There is an ongoing debate over the most effective approaches to coordinating crisis response. One school of thought stresses a preestablished hierarchical command and control system that uses authority to synchronize efforts across organizational and jurisdictional boundaries (e.g., Hunt et al. 2014). The other school argues that the hierarchical approach to coordination lacks flexibility and limits the timely exchange of information and resources (Waugh and Streib 2006). A network approach facilitates the development of horizontal interorganizational and cross‐sector relationships and provides flexible and adaptable structures for coordination (Boin and ’t Hart 2003; Comfort 2007).

Many scholars have noted that it is necessary to move beyond this debate, emphasizing hybrid modes of coordination to increase the response capacity for complex disasters (Christensen, Lægreid, and Rykkja 2015; Nowell and Steelman 2019). An effective coordination structure should build on “an intricate mix of limited (but effective) central governance and a high level of self‐organization” (Ansell, Boin, and Keller 2010, 203). Yet both vertical and horizontal coordination can encounter hurdles. When to step in and what actions to take can be complicated decisions for a central government to make (Boin and ’t Hart 2012).

Governance Structure for Crisis Coordination

A network approach cannot replace a clear hierarchy or exclude the important role of government (Boin and ’t Hart 2003). Different from managing a single organization, governing a complex system requires network management to gather member organizations, define rules and processes for coordination, mediate differences and conflicts, and bridge connections across political and jurisdictional boundaries (Agranoff and McGuire 2001).

Given the large number and diverse range of organizations involved in crisis response, identifying the most effective governance structure has been a major concern and challenge (Kapucu and Hu 2020; Provan and Kenis 2008). The governance mode of one lead agency may work well in a small‐scale crisis in which a single organization (such as a local county emergency management office) can coordinate preparedness and response efforts. However, in response to large‐scale transboundary crises, multilevel response networks are needed. Their complex and dynamic nature is best suited to uncertain and constantly evolving circumstances and managing the wide range of actors required for effective response (Comfort 2019). The governance capacity of a single lead agency often constrains its ability to coordinate multiplex networks (Kapucu and Hu 2016). A core group of organizations, rather than a single lead agency, often must take responsibility for coordinating resource allocation, information sharing, and timely decision‐making.

Paired Assistance Programs for Increasing Medical Surge Capacity

To improve the medical surge capacity of Wuhan, China's National Health Commission (NHC) 2 required provincial health commissions to organize special medical teams to assist the city. As the situation worsened, the Central Leadership Group for the COVID‐19 response decided to reinitiate PAPs to avoid the emergence of a second epicenter.

Originating in the 1960s, PAPs are institutionalized as mechanisms for transferring resources from provinces in relatively developed regions to provinces or cities in less developed areas, under the coordination of a central government. PAPs have mainly been implemented to assist with reducing poverty, increasing industrial development, improving education, and providing disaster relief (Li 2015). This assistance has taken the form of financial investments in public infrastructure construction, dispatching of professional personnel, and provision of training in the areas of education, public health, and economic development (Li 2015). After the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China, affected rural counties in Sichuan Province received a variety of assistance from 19 provinces, including infrastructure and facilities restoration, medical support, job training, and rebuilding of residential communities (Zhong and Lu 2018). In return, affected counties offered favorable tax incentives and land use policies to enterprises in provinces offering aid. Assisted counties and assisting provinces established long‐term cooperation through joint investment in industrial parks and state‐owned enterprises, as well as other types of economic development related to agriculture and tourism. Teams and personnel offering assistance received nationwide recognition and opportunities for career advancement (Zhang and Tang 2020).

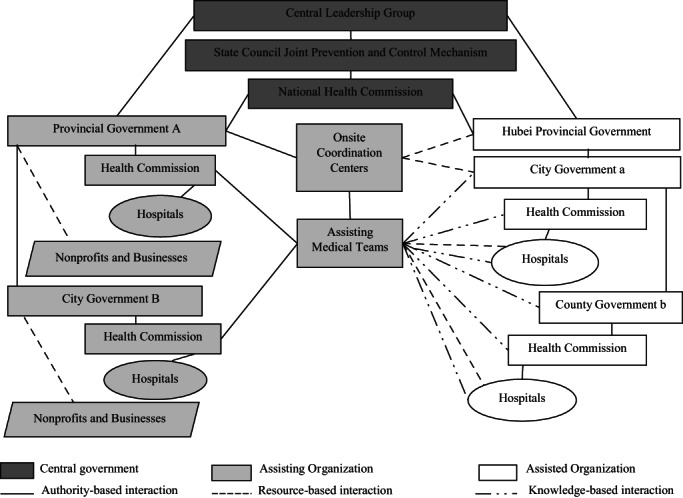

The NHC modified the model of “one province assisting one county” and requested that 19 provinces assist 16 severely impacted cities in Hubei. This decision was based on the evolving epidemic, medical personnel reserves of the provinces providing assistance, and shortages of medical resources for the cities in need (Xinhua News Agency 2020d). Figure 1 depicts the operation of PAP programs in China in response to COVID‐19. At first glance, they may appear to reflect the use of a centralized coordination model. However, a close examination of the operation of these PAPs reveals a hybrid mode of coordination. Central, provincial, and city governments all played different roles in PAP initiation, operation, and management. A variety of interactions occurred among a wide range of organizations, including authority compliance, resource coordination, and knowledge sharing.

Figure 1.

Illustration of PAP Operation in China in Response to COVID‐19

PAP Initiation, Operation, and Governance Structures

In China, PAPs function based on multilevel networks consisting of central, provincial, and city governments, as well as hospitals and various types of health care service providers and nonprofits (Zhang and Tang 2020). Multiple agencies have coordinated the initiation and management of PAPs in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Polycentric structures have been operationalized across all levels through various types of interactions among government entities, facilitated by mechanisms ensuring timely communication and joint decision‐making.

Leadership has consisted of the Central Leadership Group, State Council for Joint Prevention and Control, NHC, provincial health commissions, and provincial and city governments. All of these groups have played a part in leading different tiers of coordination at different stages of PAP development. At the initiation stage, the Central Leadership Group, with Premier Keqiang Li as the appointed group leader, utilized it administrative authority to motivate provinces to comply with the policy and offer assistance. The State Council for Joint Prevention and Control served as an interagency connective network. The NHC acted as the lead agency, coordinating with the other 31 member ministries, such as the Ministry of Emergency Management (MEM), Ministry of Public Security, and National Development and Reform Commission. The MEM was established as a cabinet agency in 2018 to manage natural hazards and technological disasters. The NHC has the authority, given by the Central Leadership Group, to create assistance pairs and coordinate efforts among provincial governments (Xinhua News Agency 2020b).

Provincial governments providing assistance served as coordinators of resources within their respective provinces. The Hubei provincial government collected and aggregated demands for medical resources, which were then used to configure paired relationships. Called on by the NHC, provincial health commissions in provinces providing assistance took immediate action to collect resources and enlist volunteer medical professionals. These provincial governments directed their health commissions to organize medical teams to provide specialized assistance, and affiliated hospitals mobilized medical personnel to join those teams on a voluntary basis. Cities within these provinces also worked with their own health commissions and hospitals to mobilize medical personnel and supplies (Xinhua News Agency 2020b). Prior to PAP initiation, many nonprofit organizations had already spontaneously mobilized, collected, and transported medical resources to Hubei (Xinhua News Agency 2020c). Their efforts were later incorporated into PAP operations through the coordination of the provincial and city governments offering assistance.

On‐site coordination centers were established in Hubei cities to facilitate communication with provinces providing assistance and coordinate the dispatching of medical teams and transfer of resources to Hubei. These coordination centers consisted of working groups and expert commissions. Their members were selected from provincial government personnel of the provinces providing assistance. Coordination centers worked with assisted city governments and health commissions to reallocate medical resources to hospitals. On‐site coordination centers were able to help medical teams from outside Hubei settle into affected cities and reorganize into effective task groups in designated hospitals. On‐site coordination centers also provided logistical support to visiting medical teams so that they could concentrate on patient treatment (Xinhua News Agency 2020a). For instance, on‐site coordination centers communicated directly with local jurisdictions to authorize the transportation of medical resources in cities on lockdown.

Hybrid Coordination of Medical Personnel and Resources

These PAPs sought to achieve collaborative performance through both vertical and horizontal coordination of medical resources. Interactions between the assisting and assisted organizations were frequent and many were self‐organized, though they were all subject to the unified coordination structure established by the central government. Provinces provided different types of assistance to meet the various demands of cities in need.

As shown in table 1, authority‐based interactions occurred between higher and lower levels of government and affiliated agencies and organizations. For example, provincial governments complied with the command of the Central Leadership Group, and hospitals reacted to the mobilization of health commissions. Horizontal coordination of medical personnel and resources occurred within the assisting provinces and between assisting and assisted parties. Medical professionals, personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, and other supplies were dispatched from provinces and cities providing assistance to Hubei Province.

Table 1.

Critical Interactions among Key PAP Actors

| Interaction Type | Stage | Actors and Their Interactions | Outputs and Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authority compliance | PAP initiation | Vertical interactions

|

|

| Resource coordination | PAP operation | Horizontal interactions

|

|

| Knowledge sharing | PAP operation | Horizontal interactions

|

|

Self‐organized knowledge sharing frequently occurred among visiting medical teams, hospitals treating the infected, city governments, and their health commissions. Medical teams not only provided urgent treatment to patients at affected hospitals, but also offered suggestions for community prevention and epidemiological surveillance to city governments and health commissions. Furthermore, visiting medical teams offered training to hospital staff and shared best practices for treating patients and preventing infection.

PAP Assessment

The PAP programs used hybrid coordination to rapidly mobilize and reallocate medical personnel and other resources and assist severely impacted provinces in a timely manner. The centralized political‐administrative system enabled rapid coordination across different levels of government. More importantly, hybrid structures and coordination facilitated timely information exchange, efficient resource mobilization, and allocation. The operation of PAPs reinforced the essential role of hybrid coordination for increasing the disaster response capacity (Christensen, Lægreid, and Rykkja 2015; Nowell and Steelman 2019). It also highlights the importance of governance mechanisms to facilitate coordination for multilevel crisis response (Kapucu and Hu 2020).

From late January to early February, more than 30,000 medical staff were sent to Wuhan and 11,225 doctors and nurses dispatched from 19 assisting provinces and cities to other areas in Hubei (Sina News 2020). Additional assistance included ambulances, hundreds of ventilators, PPE, more than 1 billion renminbi (RMB) in financial donations, and countless daily essential supplies. 3 The medical assistance alleviated pressure on Hubei's public health care system, decreased the death toll, and slowed down the spread of the disease (Xinhua News Agency 2020a).

There were some challenges to efficient PAP implementation in the early stages. Interagency coordination was not smooth at the central level. Although charged by the State Council, the NHC's coordination capacity was constrained by a lack of strong collaborative relationships and mutual trust prior to the COVID‐19 outbreak (Tong 2020). For example, the NHC needed to coordinate with the Ministry of Public Security to regulate transportation and population flow, but the agencies had seldom worked together prior to the outbreak of COVID‐19.

In addition, city governments’ coordination with nonprofit organizations and businesses was not well‐organized in the early stages of the response. China's government still dominates all aspects of emergency management, though the role of civil society is being increasingly recognized, especially since the Wenchuan earthquake of 2008 (Hu and Zhang 2020). Seeking coordination from the nonprofit sector, the Wuhan city government designated the Wuhan Red Cross and Wuhan Charity Foundation for donation reception and distribution. However, because of a lack of guidance, prior coordination, and limited capacity, these two nonprofit organizations were not able to handle the enormous influx of medical resources and donations (Xinhua News Agency 2020c). The capacity of these PAPs could be further strengthened by building systematic platforms and processes to better engage the nonprofit and private sectors when responding to catastrophic events.

Implications for Coping with the Medical Surge in the United States

Because of differences in government systems and health care infrastructure, PAP implementation in China may not be directly applicable to the United States and other countries facing medical surges in response to COVID‐19. However, PAP operation speaks to a classic debate regarding coordination and carries important implications for crisis response. Furthermore, PAPs establish multiplex governance systems to facilitate timely knowledge sharing and coordination of resources among a wide range of organizations in complex response networks. As such, they highlight the importance of network management in governing multilevel networks when dealing with public health crises.

Hybrid Coordination in a Decentralized Governance System

Regardless of the government system in place, the response to COVID‐19 demands a hybrid mode of coordination across political and jurisdictional boundaries. As the pandemic continues to worsen in the United States, medical surge capacity has become a crucial aspect of the response to COVID‐19. City, county, and state governments have been overwhelmed by its rapid spread and requested assistance from higher levels of government. The U.S. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability (MSCC) management system was built on the principles of emergency management and the Incident Command System (ICS). 4 The MSCC management system serves to guide the public health system in preparing for and responding to health emergencies. It includes six layers of coordination within and across government jurisdictions. This multitiered system stresses interstate regional coordination and federal support to state and local governments in the face of a major public health crisis (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] 2007).

At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is the lead agency in the U.S. response to COVID‐19, with federal coordination and support provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established a COVID‐19 incident management system and activated pandemic preparedness and response plans, providing guidance, specific measures, and technical assistance to state and local governments U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] 2020). State health departments are the principal government entities developing state policies and standards, implementing national mandates, and generally responding to COVID‐19 (HHS 2020). Approximately 3,000 local health departments are the front line of the government's public health care infrastructure (Institute of Medicine 2002).

After President Donald Trump declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020, FEMA took a more substantial role in coordinating with state and local governments to mount a COVID‐19 crisis response. To increase the availability of medical resources, FEMA established a supply chain stabilization task force, procured medical supplies from the global market, and leveraged the capacity of the commercial industry (including major vendors such as General Electric and Philips) to produce ventilators. FEMA allocated critical resources such as ventilators to the highly impacted areas in greatest need (FEMA 2020a, 2020b). The HHS has enacted the National Disaster Medical System and deployed teams to provide medical care and behavioral health services and assist with operational mortuary responses in the hardest‐hit states (Dawson 2020).

To solve the shortage of medical professionals, state governments have sought help from society. For instance, more than 90,000 retired and active health care professionals signed up online to volunteer to work in hospitals in New York, including 25,000 from outside the state (Hong 2020). However, the severe shortage of ventilators and PPE remained unresolved as of early April. The federal government has only a limited stockpile of ventilators and PPE that can be allocated to severely impacted states (Weixel 2020). At the interstate coordination level, states have been hesitant to share medical personnel, PPE, and other supplies because they seek to keep these critical medical resources immediately available for their own residents. Therefore, the use of interstate mutual aid agreements such as the emergency management assistance compact (EMAC) has been limited (NEMA 2020), despite FEMA's guidance that states with excess resources should “consider using EMAC to offer resources” to other states in urgent need (FEMA 2020b, 1).

PAP operation in China in response to catastrophic events highlights the necessity of horizontal regional coordination with facilitation by a central government. In the United States, individual states are expected to share important data, communicate safety information, plan incident action, and assist other states in need of medical personnel and resources (HHS 2007). The EMAC and other mutual aid agreements provide guidance for states seeking to facilitate and streamline coordination of critically needed resources. 5 EMAC has been effective in response to natural disasters such as hurricanes (Kapucu, Augustin, and Garayev 2009) because these types of events tend to impact only a few states in a region within a limited time frame. Since COVID‐19 has impacted all 50 states, its ability to facilitate interstate coordination remains limited (NEMA 2020). In contrast to what was seen in China, hard‐hit states such as New York reached out to other states for ventilator donations, but because there was little facilitation by the federal government, weeks passed before there was a response (NEMA 2020). Better coordination is needed to operationalize existing mechanisms such as EMAC at the interstate level to cope with this type of medical surge in a timely manner.

Governance Mechanisms in Multilevel Response Networks

In addition to its centralized political‐administrative system, the success of PAPs in China can be attributed to multilevel governance mechanisms that facilitate communication and coordination across government levels. The U.S. system of federalism concentrates only limited power in the federal government and empowers each state to operate their own public health care infrastructure. State governments are independent decision‐making centers with high levels of autonomy regarding how to mobilize and allocate state resources to respond to COVID‐19 and work with other state governments in disaster response. Although the declaration of a national emergency empowers the federal government to concentrate formal decision‐making power, preexisting distrust in the federal government and bureaucratic politics have prevented smooth coordination among federal, state, and local governments (Weixel 2020). The lack of coordination between the federal government and states in bidding for critical medical equipment such as ventilators and PPE have been particularly criticized (Weixel 2020).

With such a decentralized government system, it is unrealistic to attempt to replicate the Chinese PAP model and expect timely support for reallocating medical resources at the national level. However, governance mechanisms can be better utilized to ensure effective communication and coordination among FEMA, HHS/CDC, and state and local governments, as well as among the various state government entities. Therefore, beyond mutual aid agreements such as EMAC, other types of platforms and mechanisms are needed to stimulate greater resource coordination among state governments and ensure cross‐state linkages for deliberation, knowledge sharing, and the distribution of medical resources. Clear coordination is needed to orchestrate action by connecting public health and emergency management agencies and health care delivery systems.

The National Emergency Management Association is a nonprofit organization that manages the daily operations of the EMAC and provides training and resources to state emergency management agencies regarding its operation and reimbursement process. It does not have authority over state governments to guide their level of involvement in resource allocation. As the pandemic continues to develop, the need for network management will grow ever‐more prominent; this situation should motivate greater guidance from the federal government to state and local governments and facilitate interstate coordination. Agencies with response capacity and legitimacy such as FEMA need to convene platforms for state governments to initiate collaboration, coordinate purchasing orders, and bridge communication among the states to avoid unnecessary competition for resources.

Conclusion

This article reveals important implications for crisis coordination. It is beyond the scope of this study to compare the two countries’ overall response to COVID‐19. Rather, this article is a concerted effort to analyze the initiation, operation, and function of PAPs in China to improve medical surge capacity in the hardest‐hit Hubei Province. It is crucial to apply hybrid modes of coordination that build upon the strengths of a hierarchical structure and existing horizontal relationships. Second, the response to COVID‐19 requires the engagement of government agencies at all levels, as well as a wide range of organizations from the nonprofit and private sectors. Governing such multilevel, multiscale response networks demands the institutionalization of governance mechanisms and processes to ensure effective communication and coordination at different levels of government and across political jurisdictions. Government agencies with legitimacy and response capacity need to serve as network managers to connect actors involved and solve any potential conflicts during crisis response.

Biographies

Qian Hu is associate professor in the School of Public Administration at the University of Central Florida. Her current research interests include emergency management, collaborative governance, organizational networks, and scholarship of teaching and learning. Her work has been published in journals such as Public Administration Review, the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Public Management Review, the American Review of Public Administration, and Administration & Society.

Email: qian.Hu@ucf.edu

Haibo Zhang is professor and director of the Center for Risk, Disaster and Crisis Management in the School of Government at Nanjing University, China. His research interests include emergency management networks, social media and crisis communication, organizational and policy learning, and social risk governance in China. His work has been published in journals such as Safety Science, Disasters, Risk Analysis, the Journal of Public Affairs Education, and the Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis.

Email: zhb@nju.edu.cn

Naim Kapucu is Pegasus Professor of Public Administration and Policy and director of the School of Public Administration at the University of Central Florida. His main research interests are emergency and crisis management, decision‐making in complex environments, network governance, leadership, and social inquiry and public policy. He has published 10 books and more than 100 journal articles. His most recent book is Network Governance: Concepts, Theories, and Applications (Routledge, 2020), coauthored with Qian Hu.

Email: kapucu@ucf.edu

Wu Chen is a doctoral candidate and research associate in the Center on Risk, Disaster and Crisis Management in the School of Government at Nanjing University. He was a visiting scholar in the School of Public Administration at the University of Central Florida. His most recent publication appeared in the journal of Safety Science.

Email: dg1606017@smail.nju.edu.cn

Notes

The City of Wuhan is not included in these cities, as Wuhan received national‐level assistance from all provinces.

The NHC is a cabinet‐level executive department of the State Council in China. Like the Department of Health and Human Services in the United States, it has authority and responsibility for disease prevention and control at the national level.

These numbers were aggregated by the authors after collecting information from various newspaper articles and government reports.

The ICS is the underlying governance structure of the U.S. National Incident Management Systems. ICS creates centralized planning and hierarchy of command through establishing a single incident commander in charge, with the support from the staff, including a public information officer, a safety officer, and a liaison officer. The ICS also includes other sets of policy tools to guide joint decision‐making and coordination among government agencies (Moynihan, 2009; Nowell and Steelman 2019). More information can be found at https://www.fema.gov/incident‐command‐system‐resources.

For a detailed discussion of EMAC and its operation, see https://www.emacweb.org/.

References

- Agranoff, Robert , and McGuire Michael. 2001. Big Questions in Public Network Management Research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11(3): 295–326. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, Chris , Boin Arjen, and Keller Ann. 2010. Managing Transboundary Crisis: Identifying the Building Blocks of an Effective Response System. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 18(4): 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, Arjen , and Hart Paul ’t. 2003. Public Leadership in Times of Crisis: Mission Impossible. Public Administration Review 63(5): 544–53. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, Arjen , and Hart Paul ‘t. 2012. Aligning Executive Action in Times of Adversity: The Politics of Crisis Coordination. In Executive Politics in Times of Crises, edited by Lodge Martin and Wegrich Kai, 179–96. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Tom , Lægreid Per, and Rykkja Lisa H.. 2015. Organizing for Crisis Management: Building Governance Capacity and Legitimacy. Public Administration Review 76(6): 887–97. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, Louise K. 2007. Crisis Management in Hindsight: Cognition, Communication, Coordination, and Control. Special issue, Public Administration Review 67: 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, Louise K. 2019. The Dynamics of Risk.: Changing Technologies and Collective Action in Seismic Events. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Linsey . 2020. The National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) and the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Issue Brief, Kaiser Family Foundation, April 22. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus‐covid‐19/issue‐brief/the‐national‐disaster‐medical‐system‐ndms‐and‐the‐covid‐19‐pandemic/ [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 2020a. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic: Supply Chain Stabilization Task Force. March 30. https://www.fema.gov/fema‐supply‐chain‐stabilization‐task‐force [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) . 2020b. Letter to Emergency Managers Requesting Action on Critical Steps. March 27. https://www.fema.gov/news‐release/2020/03/27/fema‐administrator‐march‐27‐2020‐letter‐emergency‐managers‐requesting‐action [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Hong, Nicole . 2020. Volunteers Rushed to Help New York Hospitals. They Found a Bottleneck. New York Times, April 8. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/nyregion/coronavirus‐new‐york‐volunteers.html [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Hu, Qian , and Zhang Haibo. 2020. Incorporating Emergency Management into Public Administration Education: The Case of China. Journal of Public Affairs Education 26(2): 1–22. 10.1080/15236803.2019.1702364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Sonya , Smith Kelly, Hamerton Heather, and Sargisson Rebecca.J.. 2014. An Incident Control Centre in Action: Response to the Rena Oil Spill in New Zealand. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 22(1): 63–6. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . 2002. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed]

- Kapucu, Naim , Augustin Maria‐Elena, and Garayev Vener. 2009. Interstate Partnerships in Emergency Management: Emergency Management Assistance Compact in Response to Catastrophic Disasters. Public Administration Review 69(2): 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, Naim , and Hu Qian. 2016. Understanding Multiplexity of Collaborative Emergency Management Networks. American Review of Public Administration 46(4): 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, Naim , and Hu Qian. 2020. Network Governance: Concepts, Theories, and Applications. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. 2015. Defining the Paired‐Assistance Policy (PAP): A Perspective of Political Gifts. [In Chinese]. Comparative Economics and Social Systems 30(6): 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, Donald P. 2009. The Network Governance of Crisis Response: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19(4): 895–915. [Google Scholar]

- National Emergency Management Association (NEMA) . 2020. California Shares Lifesaving Ventilators with Hard Hit States through EMAC. News release, April 9. https://www.nga.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/04/CA‐EMAC‐Announcement.pdf [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Nowell, Brenda , and Steelman Toddi. 2019. Beyond ICS: How Should We Govern Complex Disasters in the United States? Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 16(2). 10.1515/jhsem-2018-0067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Provan, Keith G. , and Kenis Patrick. 2008. Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management and Effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(2): 229–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sina News . 2020. National Health Commission Has Sent 344 Medical Teams and 42,332 Doctors and Nurses to Support Wuhan. March 3. http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2020‐03‐03/doc‐iimxxstf6071691.shtml [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Tong, Xing . 2020. Routine and Nonroutine Emergency Management. Journal of Guangzhou University 19(2): 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) . 2007. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability: A Management System for Integrating Medical and Health Resources During Large‐Scale Emergencies. 2nd ed. September. https://www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/documents/mscc080626.pdf [accessed July 14, 2020].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) . 2020. PanCAP Adapted U.S. Government COVID‐19 Response Plan. March 13. https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6819‐covid‐19‐response‐plan/d367f758bec47cad361f/optimized/full.pdf [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Waugh, William L., Jr. , and Streib Gregory. 2006. Collaboration and Leadership for Effective Emergency Management. Special issue, Public Administration Review 66: 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Weixel, Nathaniel . 2020. Shortage of Medical Gear Sparks Bidding War among States. The Hill, March 30. https://thehill.com/homenews/state‐watch/490263‐shortage‐of‐medical‐gear‐sparks‐bidding‐war‐among‐states [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Wuhan Health Commission . 2019. Brief Report of Wuhan Healthcare Development in the Year of 2018. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/upload/file/20191205/1575536693972018707.pdf [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Xinhua News Agency . 2020a. Documentary of the Paired Assistance Program in Response to COVID‐19. Xinhua Net. February 17. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020‐02/17/c_1125588620.htm [accessed February 17, 2020].

- Xinhua News Agency . 2020b. National Health Commission Led Joint Efforts to Combat COVID‐19 the Crisis. January 22. http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2020‐01/22/content_5471437.htm [accessed July 14, 2020].

- Xinhua News Agency . 2020c. Red Cross Has Exceeded 600 Million but Resources Relocation Is Problematic. January 31. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020‐01/31/c_1125517347.htm [accessed January 31, 2020].

- Xinhua News Agency . 2020d. Reinitiating the Paired Assistance Programs (PAPs) to Coordinate All Activities to Fight against the COVID‐19. February 12. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020‐02/12/c_1125561937.htm [accessed February 12, 2020].

- Zhang, Haibo , and Tang Guijuan. 2020. Paired Assistance Policy and Recovery from the Wenchuan Earthquake: A Network Perspective. Disasters. Published online October 10. 10.1111/disa.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Kaibin , and Lu Xiaoli. 2018. Exploring the Administrative Mechanism of China's Paired Assistance to Disaster Affected Areas Programme. Disasters 42(3): 590–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]