Abstract

Objective

Emerging evidence suggests that the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic may be negatively impacting mental health. The impact on eating and exercise behaviors is, however, currently unknown. This study aimed to identify changes in eating and exercise behaviors in an Australian sample among individuals with an eating disorder, and the general population, amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic outbreak.

Method

A total of 5,469 participants, 180 of whom self‐reported an eating disorder history, completed questions relating to changes in eating and exercise behaviors since the emergence of the pandemic, as part of the COLLATE (COvid‐19 and you: mentaL heaLth in AusTralia now survEy) project; a national survey launched in Australia on April 1, 2020.

Results

In the eating disorders group, increased restricting, binge eating, purging, and exercise behaviors were found. In the general population, both increased restricting and binge eating behaviors were reported; however, respondents reported less exercise relative to before the pandemic.

Discussion

The findings have important implications for providing greater monitoring and support for eating disorder patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In addition, the mental and physical health impacts of changed eating and exercise behaviors in the general population need to be acknowledged and monitored for potential long‐term consequences.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, Australia, coronavirus, COVID‐19, eating disorder, national survey, pandemic

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) is an infectious respiratory illness that first affected individuals in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, and was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). Since the emergence of the virus, countries around the world have implemented various levels of preventative measures and restrictions to slow or stop its spread, including “social distancing” or “physical distancing,” which has resulted in unprecedented impacts on social interactions, employment, and the world economy. The subsequent effects on mental health are beginning to emerge, with increased levels of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety reported among the general population (Li, Wang, Xue, Zhao, & Zhu, 2020; Rossell et al., under review; Wang et al., 2020). In addition, past research has shown that disordered eating behaviors in the general population can be triggered by feelings of boredom and loneliness (Bruce & Agras, 1992), as well as feelings of distress following a disaster (Kuijer & Boyce, 2012).

Relatedly, individuals with an existing eating disorder may be at increased risk of an exacerbation of illness symptoms during the current COVID‐19 pandemic and may be vulnerable to greater levels of anxiety and stress due to increased social isolation as a result of social distancing (Touyz, Lacey, & Hay, 2020). Furthermore, anxieties around access to specific foods and/or medications, changes to routine, social support, and treatment for their illness may be triggering to their symptoms (Abbate‐Daga, Amianto, Delsedime, De‐Bacco, & Fassino, 2013; Levine, 2012; Schebendach et al., 2011; Steinglass et al., 2018; Tiller et al., 1997; Touyz et al., 2020). It is therefore critical to assess changes to disordered eating behaviors that have arisen following the COVID‐19 pandemic.

This article aimed to characterize changes in eating and exercise behaviors in Australia following the official announcement of the COVID‐10 pandemic (i.e., data collected from April 1–4, 2020). The specific aims of the article were twofold: (1) to determine changes in eating and exercise behaviors among those with a history of an eating disorder; and (2) to identify changes in eating and exercise behaviors among the general population. It was hypothesized that individuals with a self‐reported eating disorder would report increased levels of four behaviors compared to before the pandemic: restricting, binge eating, purging, and exercising. Increases in these behaviors were also expected in the general population, relative to before the pandemic. Patterns between the different types of eating and exercise behaviors were also examined for each of the groups.

1. METHOD

The study received ethical approval from the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (SUHREC) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

1.1. Design and measures

Initial findings of the COLLATE (COvid‐19 and you: mentaL heaLth in AusTralia now survEy) project in relation to changes in eating and exercise behaviors are reported here. These cross‐sectional data were collected during the first COLLATE survey in April 2020. Members of the general public residing in Australia and aged 18 years or older were invited to complete the survey, which is described in detail elsewhere (Rossell et al., under review; Tan et al., under review). Briefly, the project includes a series of anonymous online surveys, open for 72 hr from the first to fourth of each month (for 12 months). After the initial 12 monthly surveys, annual surveys will be completed until 2024. Respondents were recruited through social media and other advertisements, participant registries and non‐discriminative snowball sampling. All respondents were asked to self‐identify whether they had a lived experience of a mental illness. If they responded yes to this question, they were asked to specify the mental illness/es they had or were recovering from (with free text thereby allowing the participant to specify their mental illness unrestricted).

The first COLLATE survey included a broad range of measures aimed at assessing the mental health impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the Australian population and will be reported in detail elsewhere (for details, see Rossell et al., under review; Tan et al., under review). Briefly, the survey was composed of a range of quantitative and qualitative questions devised by the researchers regarding the effects of the pandemic (including the eating and exercise behaviors presented here), as well as the inclusion of a battery of standard self‐report psychosocial assessments to answer research questions of the broader COLLATE project. The entire survey took approximately 20 min to complete.

Only the relevant measures that are the focus of the current paper are described in detail here. Demographic and other relevant information was collected from participants, including whether they currently have or have had COVID‐19, and if they are currently in social isolation/quarantine because of potential exposure to the virus through travel or contact with a confirmed case. Current negative mood states (over the past week) were assessed with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS‐21) which allows categorical characterisation of severity ratings of depression, anxiety, and stress ranging from normal, mild, moderate, severe to extremely severe (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1996). Four questions specifically relating to eating and exercise behaviors were also included in the survey, adapted from the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE‐Q). Participants responded on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = A lot more, 2 = A little more, 3 = No difference, 4 = A little less, and 5 = A lot less). The questions were:

In the past week, have you been deliberately trying to limit the amount of food you eat or exclude any foods from your diet to influence your shape or weight ‐ more so than before the COVID‐19 pandemic? [“Restricting”]

In the past week, have you had episodes of binge eating (eating an unusually large amount of food given the circumstances) ‐ more so than before the COVID‐19 pandemic? [“Binge eating”]

In the past week, have you made yourself sick (vomit) or taken laxatives as a means of controlling your shape or weight ‐ more so than before the COVID‐19 pandemic? [“Purging”]

In the past week, have you experienced any significant changes in your exercise behaviors ‐ more so than before the COVID‐19 pandemic? [“Exercising”]

1.2. Statistical analysis

Respondents who self‐identified as having an eating disorder were analyzed separately to the rest of the sample to address the two aims of the study. As the questions asked about changes in eating and exercise behaviors compared to before the COVID‐19 pandemic (and the behaviors between groups likely differed before the pandemic), it was deemed most appropriate to conduct within‐group rather than between‐group comparisons (i.e., to identify changes in behavior for two distinct groups, not changes in behavior between groups). Therefore, descriptive statistics are presented for the eating disorder group and general population separately. To explore rank correlations between each of the different eating and exercise behavior variables for each group, Goodman‐Kruskal gamma (γ) was used, with an alpha of p = .008 (p = .05/6) to account for multiple comparisons (i.e., each of the four variables correlated with one another resulted in a total of six correlation analyses).

2. RESULTS

A total of 8,014 individuals started the first COLLATE survey. Of this, data from 5,469 respondents who completed the eating and exercise behaviors section of the survey are presented (2,545 participants dropped out by this stage of the survey (n = 2,542) or chose to not complete this section (n = 3)).

2.1. Eating disorder group

One hundred and eighty respondents reported that they currently have or have had an eating disorder. Of these respondents, one reported having a current COVID‐19 diagnosis and 11 reported being in social‐isolation or quarantine because of recent travel or contact with a confirmed COVID‐19 case. No respondents reported that they had recovered from COVID‐19. The majority self‐identified that they had a history of anorexia nervosa (n = 88), followed by bulimia nervosa (n = 23), binge‐eating disorder (n = 6), eating disorder not otherwise specified or other specified feeding or eating disorder (EDNOS or OSFED; n = 4), whereas n = 68 respondents did not specify the type of eating disorder. Of the eating disorder respondents, n = 10 reported that they were recovering or in recovery. 95.6% of the sample were female (1.7% male, 2.8% preferred to self‐describe), with a mean age of 30.47 (SD = 8.19). Reported comorbidities are presented in Table 1. Over 50% of respondents reported comorbid anxiety and mood disorders. Referring to the DASS‐21 severity ratings, over 50% of respondents in the eating disorder group showed moderate to extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (see Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Reported comorbidities in the eating disorder group and anorexia nervosa sub‐group

| Eating disorder (%) | Anorexia nervosa (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/anxiety disorder | 60.0 | 62.5 |

| Depression/depressive disorder | 50.6 | 53.4 |

| Trauma/post‐traumatic stress disorder | 15.0 | 15.9 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 8.3 | 12.5 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Dissociative identity disorder | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Psychosis | 1.1 | 1.1 |

Note: The eating disorder group contains all respondents who self‐identified as having an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa.

TABLE 2.

Severity level of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS‐21) scores

| General population (%) | Eating disorder (%) | Anorexia nervosa (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | |

| Normal | 49.9 | 59.7 | 57.5 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 34.5 | 22.1 | 33.3 | 31.0 |

| Mild | 15.8 | 8.5 | 14.7 | 11.4 | 9.0 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 4.6 | 11.5 |

| Moderate | 19.8 | 17.0 | 13.8 | 27.8 | 24.3 | 18.6 | 30.2 | 26.4 | 23.0 |

| Severe | 7.0 | 6.0 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 8.5 | 19.8 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 17.2 |

| Extremely severe | 7.4 | 8.8 | 4.0 | 27.3 | 24.9 | 15.8 | 25.6 | 28.7 | 17.2 |

| Mean (SD) score | 11.1 (9.1) | 7.2 (7.3) | 14.5 (8.8) | 18.7 (11.7) | 12.2 (9.3) | 21.0 (10.5) | 18.7 (11.9) | 13.3 (10.1) | 21.8 (10.7) |

Note: The eating disorder group contains all respondents who self‐identified as having an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa; Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS‐21) severity scores are as follows: Depression: normal (0–9), mild (10–13), moderate (14–20), severe (21–27), extremely severe (28–42); anxiety: normal (0–7), mild (8–9), moderate (10–14), severe (15–19), extremely severe (20–42); and stress: normal (0–14), mild (15–18), moderate (19–25), severe (26–33), extremely severe (34–42) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1996).

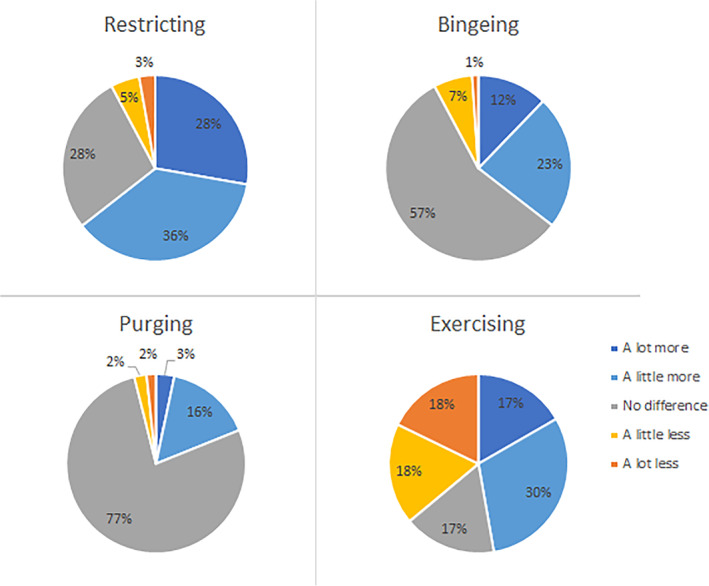

As seen in Figure 1, the majority of eating disorder respondents (64.5%) reported a little or a lot more food restriction. Of note, 35.5% reported increased binge eating behaviors, whereas 18.9% reported increased purging behaviors. Almost half of all eating disorder respondents (47.3%) reported increased exercising since the COVID‐19 pandemic. These percentages have associated standard errors of between 2.9 and 3.7%.

FIGURE 1.

Eating and exercise behaviors in the eating disorder group (n = 180) in the past week compared to before the COVID‐19 pandemic [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Only one significant correlation was observed between the different variables; a relatively strong positive relationship between changes in self‐reported binge eating and purging behaviors in the eating disorder group (γ = 0.440, p = 0.004). No other significant correlations were apparent between the different eating or exercise behavior variables.

2.2. Anorexia nervosa sub‐group

Given the high rate of anorexia nervosa reported among the eating disorder sample, further analyses were conducted on these participants separately. Of the 88 respondents reporting a history of anorexia nervosa, none currently had or had recovered from COVID‐19; however, four were self‐isolating. 97.7% of the anorexia nervosa group were female (n = 1 male, n = 1 preferred to self‐describe), and the mean age of the sample was 29.74 (7.25). Similarly to the larger eating disorder group, over 50% of the anorexia nervosa group reported comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders, and over 50% showed moderate to extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (see Tables 1 and 2).

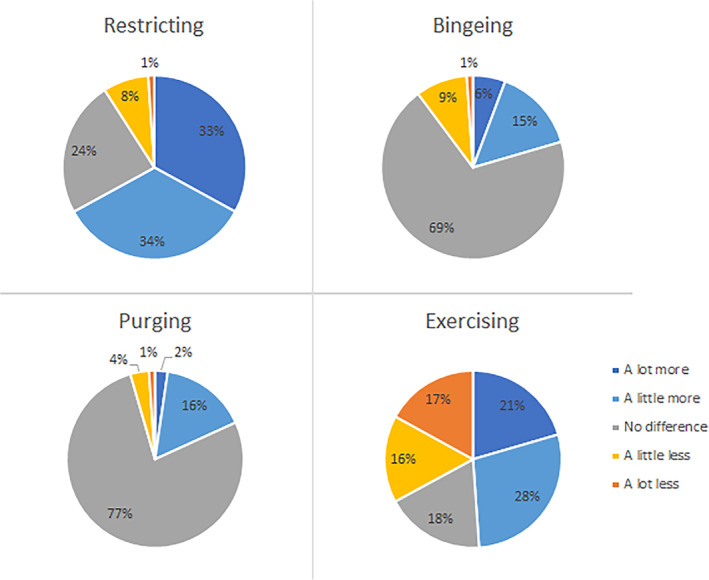

Changes to eating and exercise behaviors in the anorexia nervosa group are presented in Figure 2. Increased restricting behaviors were observed in 67.1% of this sub‐group, whereas 20.5% reported increased binge eating and 18.2% reported increased purging. Almost half of the anorexia nervosa group (48.9%) reported increased exercise. These percentages have associated standard errors of between 4.1 and 5.0%.

FIGURE 2.

Eating and exercise behaviors in the anorexia nervosa sub‐group (n = 88) in the past week compared to before the COVID‐19 pandemic [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

No significant correlations were found among the different eating or exercise behavior variables in the anorexia nervosa sub‐group.

2.3. General population

5,289 respondents who did not report a history of an eating disorder were included in the general population analyses. Of this sample, 80.0% were female (17.9% male, 2.1% preferred to self‐describe or missing), with a mean age of 40.62 (SD = 13.67). Nine respondents reported currently having COVID‐19, one reported that they had recovered from the virus, and 119 reported that they were in social isolation or quarantine following recent travel or contact with a confirmed COVID‐19 case. Most respondents in the general population sample showed “normal” levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (see Table 2).

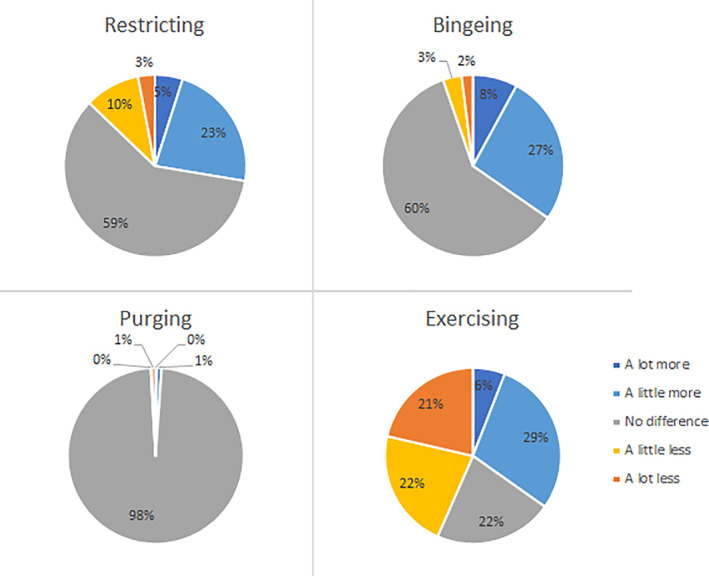

The majority of the general population reported no change in the amount of food they restricted, or their binge eating or purging behaviors. However, 27.6% of the general population reported a greater level of food restriction than before COVID‐19, and 34.6% reported increased binge eating behaviors. Exercise behaviors varied within the group, with 34.8% reporting more exercise than before the COVID‐19 pandemic, but almost half (43.4%) reporting less exercise (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Eating and exercise behaviors in the general population (n = 5,289) in the past week compared to before the COVID‐19 pandemic [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A number of significant correlations between these behavioral changes were found, including a moderate positive relationship between self‐reported binge eating and purging (γ = 0.273, p < 0.003), and a weak positive relationship between restricting and exercising (γ = 0.136, p < 0.001). There were also weak negative relationships between binge eating and exercising (γ = −0.112, p < 0.001), and restricting and binge eating (γ = −0.086, p < 0.001).

3. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify changes in eating and exercise behaviors among individuals with and without eating disorders in Australia during the early stages of the COVID‐19 pandemic. The study findings have a number of important implications.

A significant proportion of the eating disorder group reported an exacerbation of restricting, binge eating, purging, and exercise behaviors relative to before the pandemic, particularly increased restriction and exercising. While self‐reported binge eating and purging behaviors were associated with 35.5% and 18.9% increases (and were also the only correlation apparent in this group), 64.5% of the sample reported increased restricting. In addition, exercise behaviors were either increased (47.3%) or decreased (36%) in this sample, with only 17% reporting no change in this behavior. A similar pattern of results was observed for the anorexia nervosa‐specific sub‐group (but no significant correlations were found for this sample). These findings are particularly important as they suggests that even in the early stages of the pandemic (i.e., approximately 3 weeks after the official announcement by the WHO), people with an existing eating disorder were already reporting changes in eating and exercise behaviors that may be reflective of an exacerbation of disordered eating symptoms. This may be due to a number of factors, including the availability of specific foods, as well as increased stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms as a result of social distancing measures. Although levels of depression, anxiety and stress were high in the eating disorder group, and were comparable to other reported statistics in Australian eating disorder samples (Linardon et al., 2018; Phillipou, Rossell, Castle, Gurvich, & Abel, 2014), because the DASS‐21 assesses current negative mood states, it could not be used to determine whether the findings were in relation to worsening of these symptoms (as we did not have pre‐pandemic data in this cohort). However, whether these patterns in eating and exercise behaviors continue will be evaluated through the longitudinal component of the COLLATE project, which will allow detailed statistical analyses in relation to changes in depression, stress, and anxiety. It is also, however, important to note that a small portion of the sample also reported decreased restricting (8%) and binge eating (8%) and may reflect a different trajectory of symptoms in some individuals with an eating disorder. Similarly, a small number of participants in the general population sample also showed reduced restricting (13%) and binge eating (5%) behaviors.

Although the general population were found to restrict and binge eat more often than before the pandemic, no changes in purging behaviors were found. Twenty‐eight percent of the sample reported increased food restriction to influence their body weight or shape, and 35% of the sample reported increased rates of binge eating since the COVID‐19 pandemic. Changes in binge eating and restricting were negatively correlated, whereas binge eating and purging behaviors were positively correlated, as were changes in restricting and exercising. Changes to exercise varied substantially, with large proportions of the general population reporting either more or less exercise. However, almost half of respondents reported undertaking less exercise than before the COVID‐19 pandemic; though, 36% reported a greater level of exercise which may reflect positive health‐related behavior in these individuals. A negative relationship between changes in self‐reported binge eating and exercising was also found, suggesting that individuals who were binge eating more were also more likely to be exercising less. These findings may be related to a number of factors, including government restrictions which have resulted in most individuals working from home, as well as the closure of gyms and sporting clubs. These findings suggest increased rates of disordered eating behaviors and changes to exercise behaviors among the general population in the early stages of the pandemic, which may lead to important negative physical health implications if these behaviors continue through the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess changes in eating and exercise behaviors in relation to the COVID‐19 pandemic, among individuals with eating disorders as well as the general population. Limitations of the study should be noted, however, including asking participants to self‐report eating disorder history. Given the online nature of this study, diagnoses could not be independently confirmed. Although measures such as the EDE‐Q do not provide cut‐off scores for an eating disorder diagnosis, future research would benefit from its inclusion to identify probable diagnoses (see Berg et al., 2012). It should also be noted that the general population sample represented respondents without an eating disorder history and therefore will have included individuals with other mental health or medical conditions. The generalizability of findings in the general population sample is also a potential limitation. Adjusting weightings to the data in terms of age and gender based on population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics was considered, but was deemed to be inappropriate as it would have resulted in an unrepresentative eating disorder sample which was made up of mostly young females. Furthermore, limitations of the study exist in terms of the self‐selective nature of participation in this cross‐sectional online study, the short time period (1 week) asking about behavior changes, as well as the use of self‐report and retrospective assessments. In particular, the wording of the questions—i.e., asking participants how their behaviors have changed since before the pandemic—has its limitations as we are not aware of what behaviors were before the pandemic to establish whether they are indeed maladaptive, or perhaps constitute positive health‐promoting behaviors, and no specific timeframe was stated for when “before” was. The authors, however, intentionally worded the questions in this way so that participants could reflect on how their behaviors have changed since they perceived the pandemic to have begun. Furthermore, as the question regarding binge eating did not also include a sense of loss of control over eating, the question likely instead enquired about overeating. Finally, future research would benefit from expanding the time period for measuring symptom change (i.e., longer than one week) to more accurately capture the often episodic nature of disordered eating symptoms.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that there is potential for adverse psychological and health consequences in the general population because of potentially reduced exercising and increased binge eating and restricting behaviors since the COVID‐19 pandemic. Critically, an exacerbation of illness symptoms was reported in individuals with eating disorders within the initial stages of the pandemic. It is therefore crucial that we provide greater psychological support to individuals with eating disorders during this time. Given the uncertainty regarding the length of this pandemic and its rapidly evolving nature, it is essential that we continue to closely monitor these patients and provide greater support to attenuate increasing disordered eating symptoms.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AP and WLT are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Project Grants (CIA‐GNT1159953, CIA‐GNT1161609, respectively). SLR holds a Senior NHMRC Fellowship (GNT1154651), EJT (GNT1142424), and TVR (GNT1088785) hold Early Career NHMRC Fellowships. The authors would also like to thank all the participants who took the time to participate in this study.

Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1158–1165. 10.1002/eat.23317

Action Editor: Ruth Weissman

Funding information National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Grant/Award Numbers: GNT1088785, GNT1142424, GNT1154651, GNT1161609, GNT1159953

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Abbate‐Daga, G. , Amianto, F. , Delsedime, N. , De‐Bacco, C. , & Fassino, S. (2013). Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: A clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K. C. , Stiles‐Shields, E. C. , Swanson, S. A. , Peterson, C. B. , Lebow, J. , & Le Grange, D. (2012). Diagnostic concordance of the interview and questionnaire versions of the eating disorder examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(7), 850–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, B. , & Agras, W. S. (1992). Binge eating in females: A population‐based investigation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 12(4), 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijer, R. G. , & Boyce, J. A. (2012). Emotional eating and its effect on eating behaviour after a natural disaster. Appetite, 58(3), 936–939. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M. P. (2012). Loneliness and eating disorders. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Wang, Y. , Xue, J. , Zhao, N. , & Zhu, T. (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon, J. , Phillipou, A. , Newton, R. , Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M. , Jenkins, Z. , Cistullo, L. L. , & Castle, D. (2018). Testing the relative associations of different components of dietary restraint on psychological functioning in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Appetite, 128, 1–6. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S. H. , & Lovibond, P. F. (1996). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Sydney, NSW: Psychology Foundation of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipou, A. , Rossell, S. L. , Castle, D. J. , Gurvich, C. , & Abel, L. A. (2014). Square wave jerks and anxiety as distinctive biomarkers for anorexia nervosa. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 55(12), 8366–8370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossell, S. L. , Neill, E. , Phillipou, A. , Tan, E. J. , Toh, W. L. , Van Rheenen, T. , & Meyer, D. (under review). An overview of current mental health in Australia during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from the COLLATE project. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schebendach, J. E. , Mayer, L. E. , Devlin, M. J. , Attia, E. , Contento, I. R. , Wolf, R. L. , & Walsh, B. T. (2011). Food choice and diet variety in weight‐restored patients with anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(5), 732–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass, J. E. , Glasofer, D. R. , Walsh, E. , Guzman, G. , Peterson, C. B. , Walsh, B. T. , … Wonderlich, S. A. (2018). Targeting habits in anorexia nervosa: A proof‐of‐concept randomized trial. Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2584–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E. J. , Meyer, D. , Neill, E. , Phillipou, A. , Toh, W. L. , Van Rheenen, T. , & Rossell, S. L. (under review). Considerations for assessing the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health in Australia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tiller, J. M. , Sloane, G. , Schmidt, U. , Troop, N. , Power, M. , & Treasure, J. L. (1997). Social support in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 21(1), 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz, S. , Lacey, H. , & Hay, P. (2020). Eating disorders in the time of COVID‐19. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 19. 10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (2020). WHO Director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19. . Retrieved on March 11, 2020 from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.