Some diseases can be cured by medical interventions, others not. When not, are there other approaches to control or cure? One possibility is to try to publish a disease to death, a therapy strategy first proposed by my late colleague Prof. David Golde from UCLA (see below). Here I consider whether this strategy is working in the fight against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) pandemic and the associated coronavirus infectious disease‐2019 (COVID‐19).

To test this hypothesis I queried PubMed on 16 May, 2020 for citations using the search terms SARS‐CoV‐2 and/or COVID‐19. There were 12, 959 hits since January, 2020 or roughly 162 citations per day. I confirmed this by comparing this number with a PubMed search I did on 14 May, 2020. The difference of 484 citations is consistent with a recent publication rate of 220 per day. This number equates to numbers of deaths from COVID‐19 in the UK in that time. This is only for citations covered by PubMed. The figures from the World Health Organization which tracks every typescript on the virus and its disease submitted in their journals irrespective of publication would be much greater. 1

How to explain this burst of publications? Can so many high‐quality studies be done so quickly? Unlikely. In fact, of 1 556 studies of COVID‐19 listed in Clinicaltrials.gov, 1 only 249 (16%) were phase‐3 trials and fewer than 100 included more than 100 subjects. Given the baseline estimate 85% of clinical research is not useful or wrong, we may be pushing this estimate to 90 or 95% this year. 2 , 3

One explanation of this publication deluge is the opportunity the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic offers authors and journals. Some journals (but not BJH) have lowered criteria for acceptance. Publications of series of two or five subjects are appearing in high impact factor journals which would otherwise have appeared, if at all, in the Journal of Plant Biology. Although this change may be motivated by the goal to rapidly disseminate information about SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19, it is also possible some journals and authors are jumping on the SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19 bandwagons. [I am also guilty of publishing several typescripts on this subject; εκπειραζοντες αυτον οι ιερεις ινα εχωσιν κατηγοριαν αυτου (The saints have been accused of this accusation).] My mentor, Prof. Martin Cline cautioned: No data is better than bad data. 4

Other forces may be operating. Submissions to scientific and medical journals increase dramatically over the Christmas and New Year holidays and on weekends. 5 Most scientists’ laboratories are closed and clinicians not directly involved in treating persons with COVID‐19 have reduced clinical responsibilities and work from home via telemedicine. Their options: (1) help with online schooling; (2) cook dinner; (3), vacuum (Dyson V7 highly recommended); or (4) hide in your (newly designated) home office and complete a long‐delayed typescript. The choice between publish or perish has never been starker.

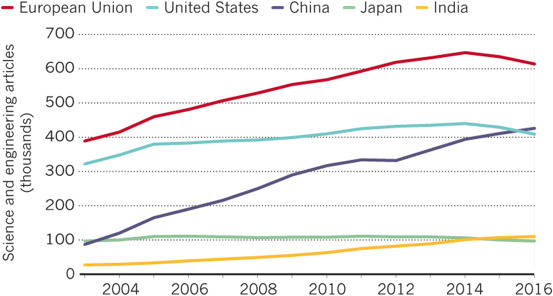

I also considered that many if not most of this surge of publications are from Chinese authors. (Fig 1) shows data on numbers of publication by geographic region and country. 6 Although China surpassed the US in 2015 they trailed the EU in 2016. This is likely to change in 2020.

Fig 1.

Scientific publications by geographic region and country. 22

Another growth industry is publication of management guidelines for SARS‐CoV‐2 and/or COVID‐19. A PubMed search on 16 May, 2020 found 599 SARS‐CoV‐2 and/or COVID‐19 guidelines. For the BJH I list only guidelines directed towards persons with haematological disorders including haematopoietic cell transplant recipients and recipients of cell therapies such as chimaeric antigen receptor (CAR)‐T cells. These include one from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 7 one from an international expert panel; 8 one from the European Bone Marrow Transplant Group (EBMT) 9 and one from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT). 10 There were 52 authors of the international expert panel guidelines making me suspicious so many physicians could agree on anything save authorship on a publication. I contacted six co‐authors I know, none \ had cared for someone with COVID‐19. Furthermore, none of these four guidelines is listed in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse. 11

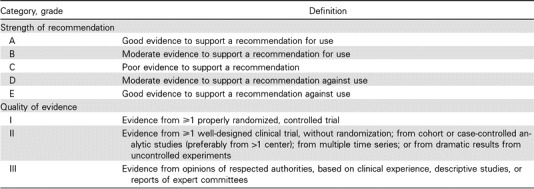

My next step was to evaluate the quality of these guidelines using criteria of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (Fig 2). 12 Readers will not be surprised the four guidelines received a C for Strength of Recommendation (Poor evidence) and a III for Quality of Evidence (Evidence from opinions of respected authorities… without clinical trials data). Nevertheless, recommendations in these guidelines, although not evidence‐based, seem sensible and may be useful. The risk is that they will be awarded the imprimatur of delivering quality health care absent anything better. Wiser people than me have commented on the value of consensus in decision making. For example, Abba Eban, a former Foreign Minister of Israel, noted: Consensus means that lots of people say collectively what nobody believes individually.

Fig 2.

Criteria of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 12

Michael Crichton, physician and author commented: Historically, the claim of consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels; it is a way to avoid debate by claiming that the matter is already settled. Whenever you hear the consensus of scientists agrees on something or other, reach for your wallet, because you're being had. Limitations of consensus guidelines and their detrimental effect on critical thinking are discussed by others, by Profs. Gianni Barosi and me and by Shaun McCann (who also evaluates guidelines on wine making). 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18

What proof have I my criticism of these guidelines is valid? Might I be biased? As a test I performed a series of controlled experiments in mice. Animals were divided into two cohorts; one was fed shredded versions of the four guidelines and the other, shredded blank paper (placebo). After a week I combined mice within each cohort and placed them in a large cage into which I put a block of cheese labelled Conquer COVID‐19 with a marker pen (sound like The Patchwork Mouse? 19 ). My initial experiments failed for two reasons: (1) the first cheese I tried was Époisses de Bourgogne. Because it has a soft rind the Conquer COVID‐19 quickly became invisible; and (2) even without the writing the mice were quickly asphyxiated (think Stinking Bishop, Pont L'Evequ or Petit Muenster). To appreciate the magnitude of this danger be advised it is illegal in France to open an Époisses de Bourgogne on a public transport. My second attempt, using Shropshire Blue, was more successful even though it was challenging to read Conquer COVID‐19 between the veins. The bottom line, however, is there was no statistically significant difference in the time it took the mice in either cohort to consume the Shropshire Blue whether they were fed shredded guidelines or placebo.

Other innovative strategies to conquer SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19 have also been tried such as having interminable meetings, perhaps a way of talking a disease to death. A bonus of these remote audio‐only meetings during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, is one can, in your sleeping costume, finish breakfast, check e‐mails and complete typescripts on SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19 to submit (see above). Unfortunately, it seems the talking cure will not cure COVID‐19. 20 (Apologies to Josef Brueur and Anna O.)

Coming back to the strategy of publishing a disease to death, we have been there before with hairy cell leukaemia. in the 1970s many people with this disease were referred to Profs. Golde and me at UCLA or Prof. Harvey Golumb at the Univ. Chicago. We were in a vigorous academic competition but the only intervention we had was splenectomy, effective in some people but not a cure in most. What to do? Golde suggested: If we can't cure hairy cell leukaemia perhaps we can publish it to death. Can it work? Who knows? We tried. Fortunately, for hairy cell leukaemia we now have cladribine, pentostatin, rituximab and interferon amongst others. For SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19 we await a vaccine and safe and effective therapies.

Lastly, we may never know if the strategy of publishing COVID‐19 to death worked because the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic may subside during or soon after this deluge of publications. Was this merely an association, correlation corelations or cause‐and‐effect? Many associations, regardless of how strong, are not cause‐and‐effect. Take, for example, the correlation between per capita cheese consumption (not only Époisses de Bourgogne) and likelihood of dying by becoming tangled in one's bedsheets. 21 Causal inference is tricky. Perhaps when the dust settles we will have time for a rigorous evaluation of what is effective (and, perhaps more importantly, what is not) and we can be better prepared for the next coronavirus pandemic.

Conflict of Interest

I have no fiscal interest in makers of Époisses de Bourgogne, Stinking Bishop, Pont L'Eveque nor Petit Muenster. However, during the lockdown shipments of these would be greatly appreciated and can be sent to 11693 San Vincente Blvd, Los Angeles, CA USA 90049‐1533.

Acknowledgement

RPG acknowledges support from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

References

- 1. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=covid&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist.

- 2. Glasziou PP, Sanders S, Hoffman T. Waste in COVID‐19 research. BMJ. 2020;369:m1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ioannis J. Why most clinical research is not useful. PLoS Medicine. 2016;13:e1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. https://www.financialpolicycouncil.org/blog/garbage-in-garbage-out-why-bad-data-is-worse-than-no-data/

- 5. Barnett A, Newburn I, Schroter S. Working 9 to 5, not the way to make an academic living: observational analysis of manuscript and peer review submission over time. BMJ. 2019;367:l6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/assets/1387/overview.pdf.

- 7. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng164.

- 8. Zeidan AM, Boddu PC, Patnaik MM. Special considerations in the management of adult patients with acute leukaemias and myeloid neoplasms in the COVID‐19 Era: Recommendations by an International Expert Panel. Lancet Haematol. 2020;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.ebmt.org/ebmt/news/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-ebmt-recommendations-update-march-23-2020.

- 10. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/ASBMT/a1e2ac9a-36d2-4e23-945c-45118b667268/UploadedImages/COVID-19_Interim_Patient_Guidelines_4_20_20.pdf).

- 11. https://health.gov/node/160.

- 12. Khan AR, Khan S, Zimmerman V, Baddour LM, Tleyjeh IM. Quality and strength of evidence of the Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and quality clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. 1996. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE. Falck‐Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Metlay JP, Armstrong KA. Annals clinical decision making: weighing evidence to inform clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barosi G, Gale RP. Is there expert consensus on expert consensus?Bone Marrow. Transplant. 2018;53:1055–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCann SR, COVID‐19, HCT and wine. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hixson, J The Patchwork Mouse. 1976; Anchor Press, New York, NY, USA; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 20. http://commentary-gonzalo86.blogspot.com/2020/04/interminable-meetings-found-ineffective.html

- 21. Zheng C, Dai R, Gale RP, Zhang MJ. Causal interference in randomized clinical trials. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/assets/1387/overview.pdf