FOR MANY STATES AND COUNTRIES, MOST COVID‐19 DEATHS OCCUR IN LTCFs

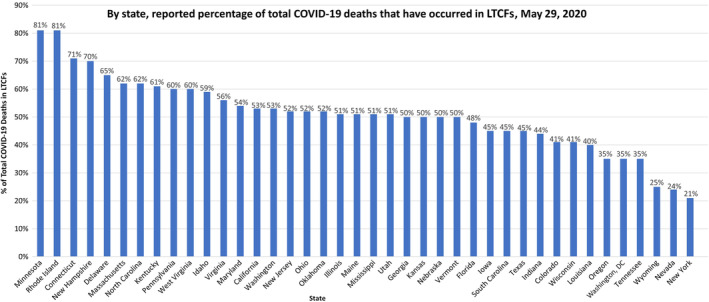

As of May 28, 2020, 26 states had 50% or more of their coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) deaths occur in long‐term care facilities (LTCFs), with Minnesota and Rhode Island at 81%, Connecticut at 71%, and New Hampshire at 70%. Among the 40 states providing LTCF death data (including Washington, DC), an average 43% of their total deaths occurred in LTCFs (n = 39,039) (Figure 1). 1 The definition of LTCF differs by state but generally includes nursing home, group home, and intermediate care facilities. Some states more recently have included assisted living facilities. Despite such alarming reports, the remaining 11 states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, and North and South Dakota) still do not report their LTCF COVID‐19 deaths.

Figure 1.

The proportions of statesʼ total coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) deaths occurring in long‐term care facilities (LTCFs) among the 40 states (including Washington, DC) reporting LTCF COVID‐19 fatalities in their tallies (11 states do not provide reports). The lower estimates may be artificially low due to numerous sources of undercounting. Original figure derived from data provided by the Kaiser Family Foundation, May 28, 2020. 1

The lowest reported frequency of total deaths of 21%, reported by New York, is most certainly a gross underestimate in light of other northeastern state reports of LTCF death counts that are three to four times higher and where, during the surge, COVID‐19–positive patients were transferred from New York 2 and New Jersey hospitals to LTCFs. Further contributing to the underestimation of LTCF deaths is that in March and part of April, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) testing was largely unavailable to LTCFs and COVID‐19 deaths were only counted as such if backed by a positive test. 3

At the national level, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relies on state as well as death certificate data to report the number of COVID‐19 deaths. With the gross undercounting of deaths in some states and the usual significant delay in the receipt of death certificates 4 (now made even worse by overwhelmed funeral homes and morgues), the current reported total number of deaths in the United States must be severely underestimated. On May 6, 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) directed LTCFs to report their confirmed or probable COVID‐19 cases to the CDC. 5 Accurate accounting of all COVID‐19 deaths (as well as cases) will allow states and the federal government to recognize that LTCFs are a major driver of total COVID‐19 deaths.

Most other countries with large numbers of LTCFs are likely also experiencing a greater than 50% rate of their COVID‐19 deaths within LTCFs. The World Health Organization estimates that half of COVID‐19 deaths in Europe and the Baltics are among their 4.1 million LTCF residents. 6 Once France began to include LTCF deaths in its count, the countryʼs death rate nearly doubled. 7 Canadaʼs National Institute on Aging indicated on May 6, 2020, that 82% of the countryʼs COVID‐19 deaths had been in long‐term care settings. 8

Belgium has the highest per capita COVID‐19 death rate in the world, at 82 per 100,000 population (compared with 31 per 100,000 in the United States). 9 Aware of COVID‐19 nursing home outbreaks, Belgium authorities included COVID‐19 cases and deaths in hospitals, nursing homes, and other congregate living settings early on, and therefore, Belgiumʼs rate is the highest likely because it does the best job of any in counting COVID‐19 probable and test‐proven cases and deaths, including those in LTCFs. 7 Without accurate counts of where cases and deaths are occurring, we will be disadvantaged in creating our management strategy.

THE PROPORTION OF COVID‐19 DEATHS IN LTCFs CONTINUES TO INCREASE ON THE DOWNSIDE OF THE SURGE

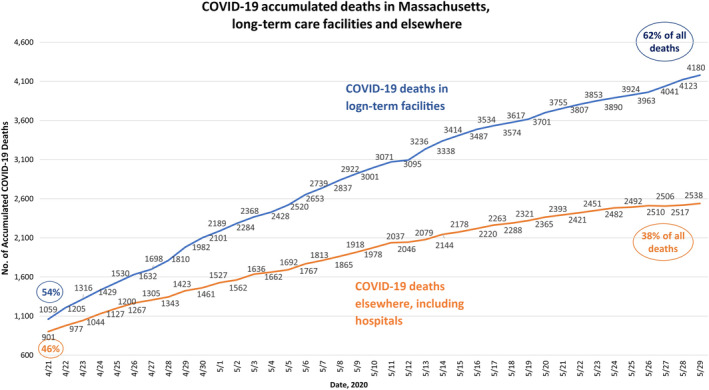

Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID‐19 Dashboard data afford additional insights into the frequency of COVID‐19 deaths over time inside and outside of LTCFs during the peak of the surge and currently when state‐wide cases and deaths are quickly declining. Since April 21, 2020, the dashboard reports mandated daily case and death data provided by LTCFs (389 nursing homes and group homes). 10 Figure 2 shows that over the past month, the proportion of deaths in Massachusetts that occur in LTCFs has steadily increased from 54% to 62%, which could indicate that the state is doing a better job of counting deaths in LTCFs or that the death rate in hospitals is decelerating relative to the rate in nursing homes or a combination of the two.

Figure 2.

The number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) deaths in long‐term care facilities versus elsewhere, including hospitals, from April 21 to May 29, 2020. Original figure derived from data provided by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID‐19 dashboards, April 21 through May 29, 2020. 10

As states begin to open up their communities and economies, LTCFs will need to be treated differently as COVID‐19 appears to have a much stronger hold on these facilities than elsewhere. LTCFs have a high density of people with a combination of the strongest risk factors for COVID‐19–associated severe illness and death: old age and multiple morbidities. The CDC indicates that 39% of the 1.3 million nursing home residents in the United States are 85 years and older. 11 According to the Massachusetts dashboard, from April 21 to May 29, 2020, people aged 80 years and older consistently constitute 63% of COVID‐19 deaths, and 98% of the deaths were associated with multiple comorbidities.

WHY LTCFs ARE SO VULNERABLE TO COVID‐19

There are also structural, care, and social characteristics that make LTCFs vulnerable to the spread of COVID‐19 and other viruses, like influenza. CMS mandates that LTCFs have infection control programs in place, including isolation measures, hygiene, laundry, food‐handling requirements, and many other specific measures. However, for most LTCFs in the United States, these measures have proved ineffective in keeping COVID‐19 out. As of May 29, 2020, 349 of the 389 Massachusetts LTCFs, or 90%, had at least one case of COVID‐19. The “Achilles heel” of these and other defenses is the high prevalence of asymptomatic transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2. 12 Asymptomatic carriers include social visitors, as well as laboratory phlebotomists, intravenous line nurses, and radiology technicians, who travel from nursing home to nursing home and have direct contact with residents. Fomites, such as a technicianʼs clothing or X‐ray equipment, can be potential vectors for SARS‐CoV‐2. 13

A second LTCF‐specific cause of spread includes dementia units, designed to allow for wandering but which facilitate viral transmission to others. Third, due to their low pay, certified nursing assistants, who constitute 64% of LTCF staff 11 (median annual salary is $27,950 14 ), often hold double‐ or triple‐duty caregiving roles. 15 Working at more than one LTCF further enables spread of COVID‐19. Such conditions place these and other staff at significant risk of infection and significant stress.

SOME EXCEPTIONS

There are countries that are exceptions to the rule that LTCFs are the sites of so many COVID‐19 outbreaks and deaths. Hong Kong 16 has had no COVID‐19 LTCF deaths, and Singapore 17 and South Korea 18 report less than 20 each. According to Terry Lum, the Director of the University of Hong Kongʼs Sau Po Centre on Aging, key reasons for COVID‐19 not infiltrating Hong Kongʼs LTCFs include 16 :

To prevent spread of COVID‐19 from hospitals, all cases are quarantined until proved multiple times to no longer be viremic.

Careful tracking of contacts is performed, and these are isolated at a separate quarantine center for 14 days, during which time frequent nasopharyngeal swab tests are performed.

All nursing homes have trained infection controllers, and emergency drills simulating influenza or SARS outbreaks are performed four times a year.

In South Korea, an additional measure includes inspections of all LTCFs. A key point for all three countries is that they enacted their emergency measures in early to late February. There are, of course, some countries, like New Zealand, that report only 20 deaths because of early and strict lockdown policies and the closing of their borders. 19

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL TOLL

Beyond the untenable death toll, COVID‐19 has caused LTCF staff, residents, and their families to endure huge stress. The usual socializing among residents no longer exists. As physical distancing practices are instituted in LTCFs and communal dining and recreational activities are canceled, LTCF residents are at greater risk of loneliness. Families and residents have become heartbroken with their inability to visit in person with one another. Family members experience significant anxiety knowing their loved ones are living in settings where there is a high risk of infection. In LTCFs where gerontologists and geriatricians aim to make residents feel like they are living more in their home and where socializing is the norm, 20 the pandemic has brought such aspirations to a halt.

As LTCFs continue their lockdowns while communities open up, we must devise thoughtful approaches to preserving quality of life and important relationships. In the absence of family and friends, already stretched‐thin nursing staff and aides do what they can to visit with residents and provide emotional care and reassurance. This is not trivial as loneliness and anxiety have been associated with depression, frailty, and progression of cognitive decline. 21 Just as virtual classrooms and meetings have become the norm for businesses, LTCFs could consider installing computer screens in residentsʼ rooms, allowing for communication between residents and their loved ones and participation in activities.

THE NEED TO MATCH THE REGULATIONS WITH THE SCIENCE

Looking forward, we must address the consequences of ongoing careful isolation and other protective measures for these vulnerable older adults. LTCFs and public health officials must determine what can be done to reduce the stress and enhance the quality of life for residents, staff, and families while keeping everyone safe. As resources become available, public health policies and state and federal regulations must match the science. For example, ubiquitous testing should replace taking temperatures, because we know that carriers can be asymptomatic. When a vaccine becomes available, anyone working at or visiting an LTCF should be among the first to be vaccinated.

Media focus on problems that LTCFs face is warranted; however, the narrative of blame and public shaming is not helpful for the residents, their families, or those who work in these healthcare settings. Instead, we need to identify the pitfalls in our interacting systems, and ways the multiple stakeholders can find common ground to support older adults in LTCFs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the conceptualization, review, and interpretation of the data and writing of the article.

Sponsorʼs Role

There was no sponsor for the production of this work.

Twitter handles of authors: @thperls, @RLauNgMD, @LisaCarusoMD

Contributor Information

Rossana Lau‐Ng, @RLauNgMDD.

Lisa B. Caruso, @LisaCarusoMD

Thomas T. Perls, Email: thperls@bu.edu, @thperls.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaiser Family Foundation . State data and policy actions to address coronavirus May 28 2020: state reports of long‐term care facility cases and deaths related to COVID‐19. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 2. Mustian J, Peltz J, Condon D. NYʼs Cuomo criticized over highest nursing home death toll. AP News. May 10, 2020. https://apnews.com/4042f05613ee4259b7a44d4466a0a02a. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 3. Clukey K, Young E. Nursing homesʼ unclear death toll has states testing corpses. Bloomberg Law; 2020https://newsbloomberglawcom/coronavirus/sleuthing-at-funeral-parlors-to-track-nursing-homes-true-toll. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 4. National Center for Health Statistics . Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease (Covid‐19): technical notes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/tech_notes.htm. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 5. National Healthcare Safety Network of the Centers for Dease Control and Prevention . LTCF COVID‐19 module. 2020. https://www.bloombergquint.com/politics/why‐the‐world‐s‐highest‐virus‐death‐rate‐is‐in‐europe‐s‐capital. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 6. Associated Press . WHO Europe: up to half of deaths in care homes. 2019. https://www.voanews.com/Covid-19-pandemic/who-europe-half-deaths-care-homes. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 7. Ainger J. Why the worldʼs highest virus death rate is in Europeʼs capital. Bloomberg News. April 25, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020‐2004‐2025/why‐the‐world‐s‐highest‐virus‐death‐rate‐is‐in‐europe‐s‐capital. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 8. MacCharles T. 82% of Canadaʼs COVID‐19 deaths have been in long‐term care, new data reveals. The Star. May 7, 2020. https://wwwthestarcom/politics/federal/2020/05/07/82‐of‐canadas‐covid‐19‐deaths‐have‐been‐in‐long‐term‐carehtml. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- 9. Johns Hopkins University of Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center . Mortality analyses. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 10. Massachusetts Department of Public Health . COVID‐19 dashboard. 2020. https://www.mass.gov/doc/covid‐19‐dashboard‐may‐29‐2020/download. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 11. Harris‐Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Lendon JP, Rome V, Valverde R, Caffrey C. Long‐term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016: data from the National Study of Long‐Term Care Providers. Vital Health Stat 3. 2016;3(43):1‐105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gandhi M, Yokoe DS, Havlir DV. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achillesʼ heel of current strategies to control Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2158‐2160. 10.1056/NEJMe2009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Beusekom M. US studies offer clues to COVID‐19 swift spread, severity. Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy News; 2020. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news‐perspective/2020/2003/us‐studies‐offer‐clues‐covid‐2019‐swift‐spread‐severity. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- 14. Salary.com . Certified nursing assistant – nursing home: salary. https://www.salary.com/tools/salary‐calculator/certified‐nursing‐assistant‐nursing‐home. Accessed May 10, 2020.

- 15. Van Houtven CH, DePasquale N, Coe NB. Essential long‐term care workers commonly hold second jobs and double‐ or triple‐duty caregiving roles. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [Epub ahead of print] https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news‐perspective/2020/03/us‐studies‐offer‐clues‐covid‐19‐swift‐spread‐severity. Accessed May 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Both R. MPs hear why Hong Kong had no Covid‐19 care home deaths. The Guardian. May 19, 2020. https://wwwtheguardiancom/world/2020/may/19/mps-hear-why-hong-kong-had-no-covid-19-care-home-deaths. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- 17. Geddie J. Eyeing lockdown exit, Singapore to test all nursing homes. Reuters; 2020. https://wwwusnewscom/news/world/articles/2020-05-08/singapore-records-768-new-covid-19-cases-total-now-21-707. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- 18. Kim H. The impact of COVID‐19 on long‐term care in South Korea and measures to address it. LTCcovidorg, International Long Term Care Policy Network; 2020. https://ltccovidorg/wp‐content/uploads/2020/05/The‐Long‐Term‐Care‐COVID19‐situation‐in‐South‐Korea‐7‐May‐2020pdf. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- 19. Cousins S. New Zealand eliminates COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1474. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koren MJ. Person‐centered care for nursing home residents: the culture‐change movement. Health Aff. 2010;29(2):312‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simard J, Volicer L. Loneliness and isolation in long‐term care and the Covid‐19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.006 [Epub ahead of print] https://www.jamda.com/article/S1525-8610(20)30373-X/fulltext. Accessed May 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]