Tribal communities across the United States face significant health and mental health disparities, including rates of suicide that far exceed those of nontribal communities. 1 Timely access to health care is limited across most rural areas in the United States, particularly in remote tribal communities. 2 , 3 It is likely that the COVID‐19 pandemic will exacerbate disparities among American Indian tribes, particularly when coupled with existing barriers to access health services. 4

In their commentary, Kakol et al (18 April 2020) 5 summarized historical and ongoing ramifications of colonization on Southwestern American Indian tribes from an infectious disease perspective, including challenges confronting those communities amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic. They comment on the need to expand telehealth to rural Southwest American Indian communities, adding to the burgeoning literature on COVID‐19 that emphasizes telehealth approaches, namely telemedicine, as a means of improving access to physical and mental health care, while maintaining social distancing. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Yet, Kakol et al omit the important consideration that broadband Internet access—required to deliver care to patients from a distance—is a barrier to rural patients, no matter how quickly providers are upskilled to deliver it. This is of particular concern in tribal communities.

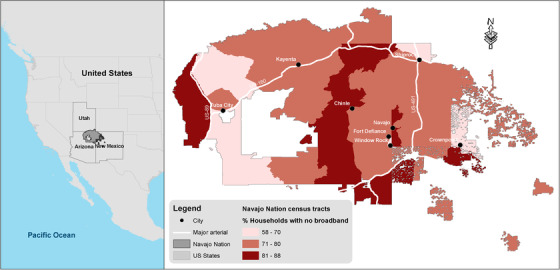

To illustrate this concern, we summarized broadband Internet service data from the 2018 American Community Survey estimates 11 for census tracts within the Navajo Nation, the largest American Indian tribe in the United States. We found that 58.1%‐87.7% of households in Navajo Nation census tracts reported not having broadband Internet service, compared to 19.6% nationally (Figure 1). Access to broadband Internet service is not only a concern for the Navajo Nation; it is a challenge facing most tribal communities in the United States. 12 , 13 Even if tribal members can access the Internet at public spaces (eg, local library or school), these locations are far from ideal for telemedicine visits, especially telemental health.

Figure 1.

The Navajo Nation spans approximately 17,544,500 acres, occupying portions of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico in the United States (left); and percent of households in Navajo census tracts reporting no access to broadband Internet service (right).

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from 2018 American Community Survey 5‐year estimates.

Without access to technology needed for telemedicine, members of rural American Indian communities are distinctly disadvantaged. Aside from barriers to access, the acceptability and effectiveness of telemedicine among tribal communities must be considered. 14 With this in mind, we agree with Kakol et al that telehealth expansion has the potential to improve access to care. However, substantial progress must be made toward increasing broadband Internet service on tribal lands before the potential of telemedicine to serve geographically dispersed but tightly woven communities, such as the Navajo Nation, can be realized.

Funding: Janessa Graves was supported in part by the Health Equity Research Center, a strategic research initiative of Washington State University. Dr Demetrius Abshire was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MD013899. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Leavitt RA, Ertl A, Sheats K, Petrosky E, Ivey‐Stephenson A, Fowler KA. Suicides among American Indian/Alaska Natives—National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 States, 2003‐2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(8):237‐242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine . Chapter 4. Addressing quality and access: promoting behavioral health in rural communities. In: Achieving Behavioral Health Equity for Children, Families, and Communities: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019: 27‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sidhu SS, Fore C, Shore JH, Tansey E. Chapter 11. Telemental health delivery for rural Native American populations in the United States. In: Jefee‐Bahloul H, Barkil‐Oteo A, Augusterfer EF, eds. Telemental Health in Resource‐limited Global Settings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2017:161‐180. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Av Dorn, RE Cooney, Sabin ML. COVID‐19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. The Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243‐1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kakol M, Upson D, Sood A. Susceptibility of Southwestern American Indian tribes to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 18]. J Rural Health. 2020. 10.1111/jrh.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wright JH, Caudill R. Remote treatment delivery in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(3):130‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and mental health for children and adolescents [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 14]. JAMA Pediatr. 2020. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rockwell KL, Gilroy AS. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID‐19 outbreak response systems. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(4):147‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chauhan V, Galwankar S, Arquilla B, et al. Novel coronavirus (COVID‐19): leveraging telemedicine to optimize care while minimizing exposures and viral transmission. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020;13(1):20‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagata JM. Rapid Scale‐up of telehealth during the COVID‐19 pandemic and implications for subspecialty care in rural areas [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 3]. J Rural Health. 2020. 10.1111/jrh.12433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. U.S. Census Bureau . American Community Survey, 2018 American Community Survey 5‐Year Estimates (2014‐2018), Table S2801. Available at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=2018%20broadband&hidePreview=true&tid=ACSST5Y2018.S2801&y=2018&vintage=2018/. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 12. Wang HL. Native Americans on Tribal Land Are “The Least Connected” to High‐Speed Internet. National Public Radio. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2018/12/06/673364305/native-americans-on-tribal-land-are-the-least-connected-to-high-speed-internet. Accessed May 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Federal Communications Commission , Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau , Wireless Telecommunications Bureau , Wireline Competition Bureau . Report on Broadband Deployment in Indian Country, Pursuant to the Repack Airwaves Yielding Better Access for Users of Modern Services Act of 2018. Federal Communications Commission; 2019. Available at: https://www.fcc.gov/document/report-broadband-deployment-indian-country. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- 14. Fraser S, Mackean T, Grant J, Hunter K, Towers K, Ivers R. Use of telehealth for health care of Indigenous peoples with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(3):4205. 10.22605/RRH4205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]