Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic is expected to last for an extended time, making strict safety precautions for office procedures unavoidable. The lockdown is going to be lifted in many areas, and strict guidelines detailing the infection control measures for aesthetic clinics are going to be of particular importance.

Methods

A virtual meeting was conducted with the members (n = 12) of the European Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery Focus Group to outline the safety protocol for the nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures for aesthetic practices in order to protect the clinic staff and the patients from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The data analysis was undertaken by thematic and iterative approach.

Results

Consensus guidelines for nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures based on current knowledge are provided for three levels: precautions before visiting the clinic, precautions during the clinic visit, and precautions after the clinic visit.

Conclusions

Sound infection control measures are mandatory for nonsurgical aesthetic practices all around the world. These may vary from country to country, but this logical approach can be customized according to the respective country laws and guidelines.

Keywords: aesthetic clinic, aesthetic medicine, consensus guidelines, coronavirus, COVID‐19

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 outbreak, caused by the SARS‐Cov2 virus, has had an unprecedented impact on global health systems. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 The economic burden induced by lockdowns will need to be carefully mitigated by “next phase” responses, which will vary with country and viral burden. While many medical practices are being run with online consultations, 10 some countries have recently decided to allow the opening of practices requiring one‐on‐one contact like dental, physiotherapy, for emergencies provided they strictly follow the guidelines detailing the infection control measures. 12 , 13

Facial aesthetic nonsurgical procedures, although having a well‐documented impact on quality of life, are not considered essential medical services and conscious efforts should made to minimize infection in this sector. The nature of our work carries a very high inherent risk of contagion for both patient and practitioner.

Due to the primary involvement of the face and neck, specifically the perioral and nasal regions, and our field is at a particular occupational hazard due to the risk of aerosol generating procedures. 13 , 14 Strict global measures are constantly evolving, and discrete guidelines need to be instituted and kept current. In our largely elective field, both staff and resources should ideally be allocated through careful protocols in order to prevent COVID‐19 infection.

2. METHOD

2.1. Focus group composition

The International European Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery (EAFPS) focus group (FG) is composed of 12 facial plastic surgeons and dermatologists from Germany, India, Italy, Lebanon, Netherlands, South Africa, Turkey, and the UK.

2.2. Focus group methods

The FG members have discussed recommendations for resuming elective nonsurgical facial aesthetic work using a topic guide. The virtual meeting was led by a facilitator (DB) and contemporaneous notes were recorded by another author (ER). The facilitator used a topic guide to ask the group members to explore the problem in question and factors for mitigation.

The topic guide was developed by the lead author after thorough literature review and cross‐checking with available guidelines in different specialties.

To minimize the number of the prompts and equal participation, the facilitator used an open questioning style.

2.3. Analysis

The transcriptions of the discussion were subsequently analyzed by a multidisciplinary research team in form of iterative and thematic approach. During this process, data were verified systematically, discussion was made around the interpretive analysis and exploring the potential research bias.

3. RESULT

Various steps were recommended in order to deliver a safe elective service, with inputs from the public and private health systems of many countries. In addition to the respective country recommendations, these guidelines hope to guide the “next phase” after the lockdown ends. The recommendation was divided into three phases for both the patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Level 1. Guidelines “before” the visit to the clinic.

Level 2. Guidelines “during” the visit to the clinic.

Level 3. Guidelines “after” the visit to the clinic.

3.1. Level 1: Guidelines “before” the visit to the clinic

3.1.1. Patient

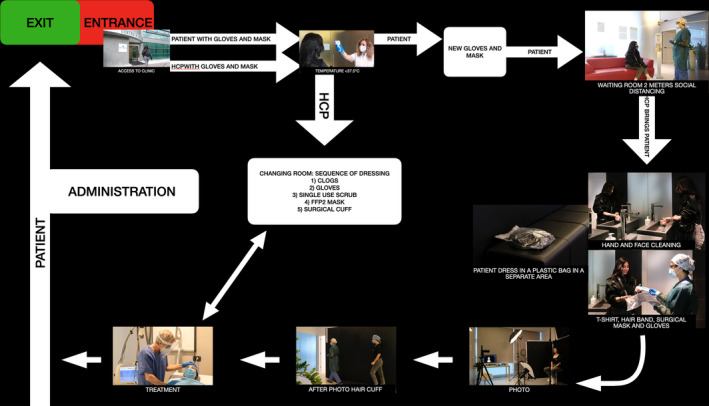

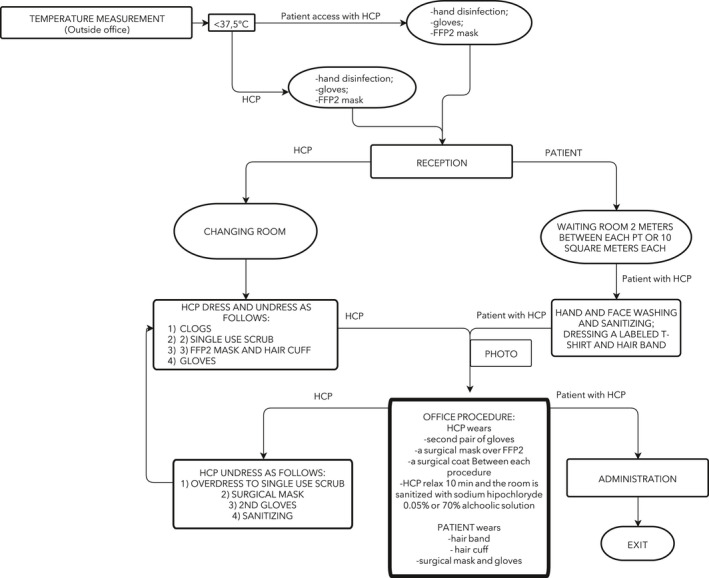

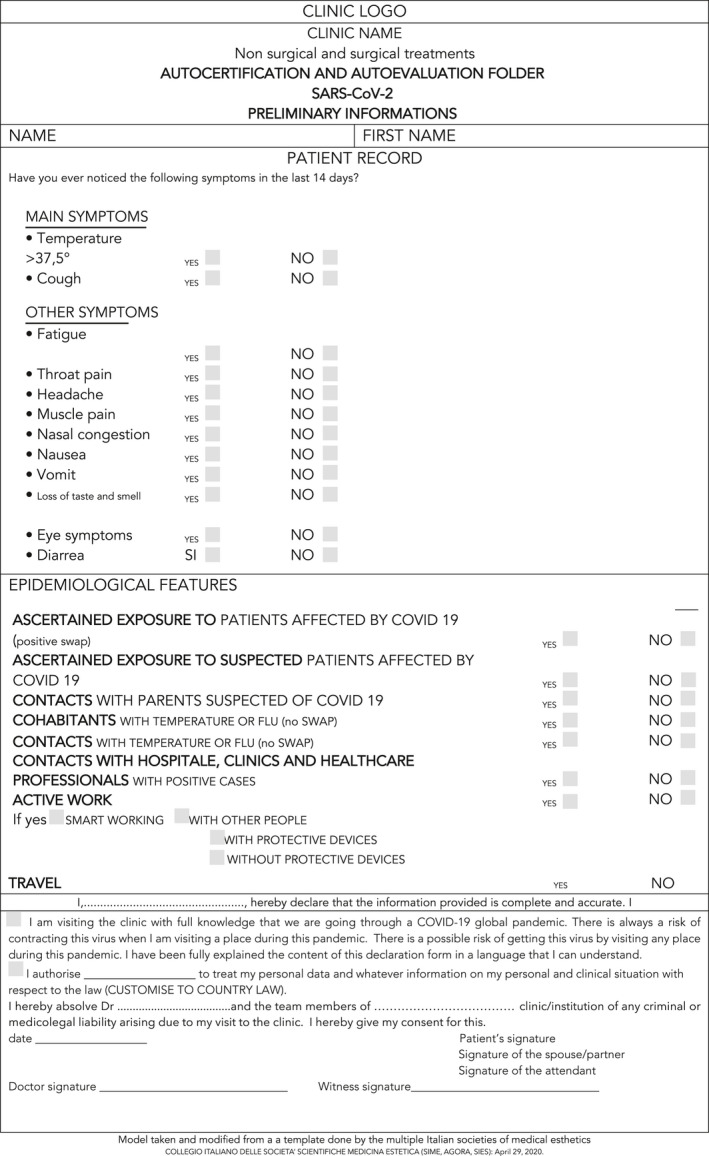

Patients should be furnished with concise, simple information regarding household behavior and the risk of contagion and transmission. It is crucial to provide patients with straightforward and clear information for precautions at home regarding coronavirus infection prevention. The SARS‐CoV‐2 virus is transmitted primarily via large droplet spread with a range of approximately 2 m, and the infection rate is known to decrease with social distancing and the wearing at least surgical masks 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 . The appointment should thus be scheduled well in advance with the recommendation of social distancing and avoidance of hospital visits or contact with COVID‐19 positive cases. Two days before the appointment, patients should receive an e‐mail with a protocol on the office routes, they will have to follow (Schemes 1 and 2) and some forms to be filled and returned 12 hours before the appointment (Scheme 3). Vital information relates to COVID‐19 contact, quarantine or symptoms during the preceding 15 days. One primary information that is essential to obtain is a declaration that the patient has not been in quarantine and has not had coronavirus symptoms in the last 15 days. If the answer to any of this is definite, the doctor must order a COVID‐19 test for the patient. Another option is to postpone the procedure for at least 2 weeks.

3.1.2. HCP and STAFF

The enclosed brochure (Scheme 4) may be distributed via e‐mail, WhatsApp, we chat or any other encrypted electronic means. A virtual appointment or telemedicine is alternative for scheduling a screening appointment upfront, with form regarding epidemiological and clinical questions to be sent to the patient that must be filled and re‐submitted 2 days prior to the appointment (Scheme 3). Patients with positive answers or suspected of infection need to undergo ELISA tests (blood samples) and swabs the 24 hours before scheduled appointment in order to get approval. Despite negative results, these patients are requested to self‐quarantine and practise social distancing because of their suspicions symptoms.

3.2. Level 2: Guidelines “during” the visit to the clinic

3.2.1. Patient

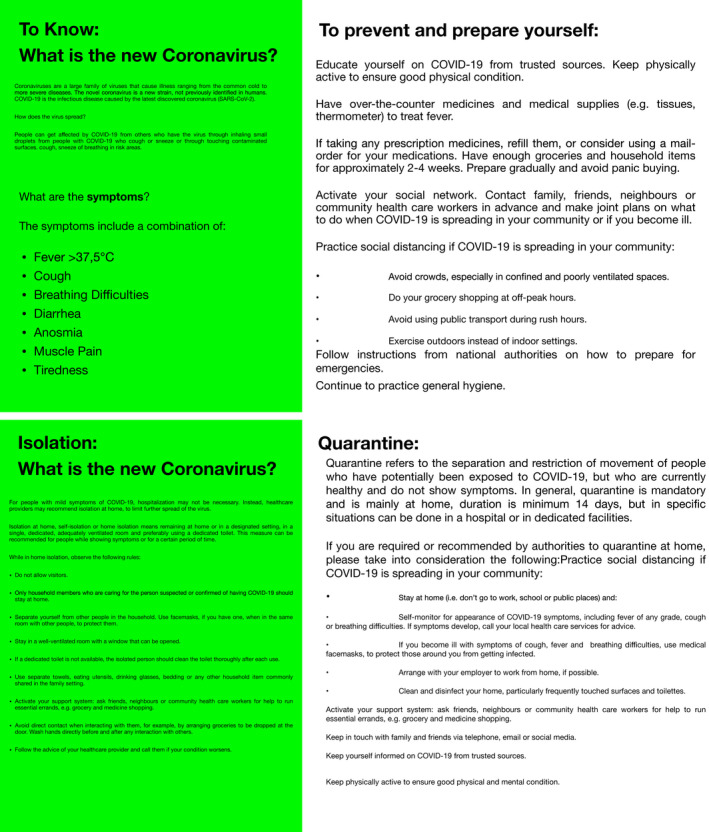

Patients are requested to attend alone, without accompanying persons or family members or pets. They must attend wearing surgical masks and gloves, are requested to respect scheduled appointment times and (Figure 1A) asked to wait outside the office when not (Figure 1B). Absolute respect for the schedule is a requirement, and patient turnaround time must be planned. People coming before or after a given time will be asked to wait outside the office or in their cars. A series of predetermined in‐office routes must be decided, and patients should get access only by following these routes. These predetermined in‐office routes must be decided with patients having access to only these. Temperature testing (Tympanic or infrared device) (Figure 1C) should be completed before access to waiting areas where a minimum of 2 m between patients and 10 m2 per person, should be maintained (Figure 2A). As soon they get to the waiting area, they will be then requested to follow a HCP who guides them to a room where they wash their hands and face (Figure 2B), they may be supplied with a labeled t‐shirt (cost is 10 euros or 12 US dollars which we give them as a gift) which they may keep after the treatment (Figure 6). After disinfecting hands and applying a headband, they progress to photography (Figure 2C). If the toilet is used, it should be flushed while the seats are covered by the lid to prevent any aerosolization. 20 Following that, they wear a hairband, disinfect their hands, and are guided to see the photographer where appropriate (Figure 3A). Meanwhile, we store their clothes and personal belongings if any, in a designated box or a plastic bag (Figure 3B) After the photograph session, an additional hair cuff is supplied and patient is directed to the treatment room. (Figure 3C). One hour per appointment is allocated to each procedure, irrespective of whether for consultation or facial treatment (injection, laser or medication) (Figure 4). The face is disinfected with sodium hypochlorite 1% solution. At the end of their session, the patient exits the office, will collect the plastic bag with their belongings from a separate room, and go to administration before leaving the clinic. It is strongly recommended that all financial transaction is carried out by electronic means avoiding physical handling of money or payment cards.

Figure 1.

A, Patient entering the clinic; (B): patient waiting outside the clinic; (C): Patient's temperature is going to be measured

Figure 2.

A, Patient waiting in the opportune area; (B): patient washing face and hands; (C): patient receive t‐shirt, hair band and a surgical mask

Figure 3.

A, Patient taking pictures; (B): patient dress in the plastic bag in the dress deposit; (C): patient going to office after photo wearing hair cap

Figure 4.

Patient treatment with Doctor

3.2.2. HCP and STAFF

Healthcare professionals follow preferably a different in‐practice route, and, at the beginning of the working day, changing into single use scrubs, FFP2 (N95) masks and additional surgical masks over them (which, along with gloves and hair cuff, has to be changed for every patient). Eye shields or protective glasses are recommended to be cleaned with sodium hypochlorite 1% after every patient consultation. If a nasal or intraoral procedure is requested (filler or medication) 0.23% povidone‐iodine solution, which is virucide, may be used in a dosage of two sprays per nostril before entering the office. 21 Oral rinse with the same solution may be used, as may eye drops of 1 drop diluted 1:100 (povidone‐iodine 10%).

Plastic/Acrylic windows panels or glass partitions should be used to decrease staff and HCP exposure. 22 In order to avoid contamination in any area of the office, all unnecessary material should be removed (leaflets, magazines, covers, water fountains, dresses, etc). In order to avoid contamination by walking frequently between different areas, it is recommended that hand sanitizers and hand‐washing facilities are readily available in all patient and staff areas and clinic staff which is encouraged to use it with high frequency making the rule of 1 glove which is the “new skin” and a second glove which is patient related and is going to be changed at every procedure. The same rule applies to water bottles and disposable glasses.

3.3. Level 3: Guidelines “after” the visit to the clinic

3.3.1. Patient

Limiting face‐to‐face interaction with nonfamily members will remain a challenge in the immediate postoperative period and should be clarified upfront in the pre‐ and postoperative procedure form. Compliance in this regard remains the responsibility of the patient (Scheme 3). A reduced frequency of posttreatment visits is recommended, with avoidance of unnecessary hospital encounters. The day after procedure, patients may send a photograph via WhatsApp or any other encrypted electronic method and communicate with an assistant regarding body temperature and clinical conditions. This is assessed in a week again, and further follow‐up is arranged as appropriate.

3.3.2. HCP and STAFF

Following every procedure, the HCP removes her/his shield, surgical masks and double gloves. Whenever possible, the window is opened for 10 minutes while a professional cleans and disinfects all devices and room with 1% sodium hypochlorite or a phenolic detergent three to four times a day. They should be well trained in hand hygiene protocols. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 This is ideally done while another patient is having photographs taken. Air disinfection can be further achieved with UV or O3 devices. 41

A minimum of 10 minutes for HCP to relax is recommended. All routine postoperative care ought to be completed via video consultation which is done between noon and 1 pm or 7 pm to 8 pm at scheduled days.

4. DISCUSSION

During the current COVID‐19 pandemic, at the very first weeks, all nonessential procedures were provisionally suspended worldwide, with re‐allocation of resources in many public and private hospitals. In‐office consultations and procedures were thus not possible. Closure of surgical theaters constituted a further preventive measure for the wide viral spread and peak particularly in China, Europe, and the USA. Currently, preliminary epidemiological experience even in high‐risk areas shows that spread is mitigated by wearing appropriate mask as a personal preventive device as well as correct hand sanitizing. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Furthermore, every medical specialty has started to develop protocols to protect staff and patients.

In response to this pandemic, our FG has developed a process to stratify procedures and clinical levels with protocols that aim to minimize the risk of contagion and the diffusion of COVID‐19 infection.

5. LIMITATION

The present study has several limitations. Although the author has utilized widely accepted method of Expert FG discussion, it is often mentioned that they act as “Expert and Judge”. 42 Also, because of the qualitative nature of the interpretation, to address the reflexivity and Hawthorne effect, the analysis was based strictly on the transcription, critical appraisal of the literature and multidisciplinary research analysis 43 to minimize bias.

6. CONCLUSION

Although, finding an optimal guideline in limited timeframe remains elusive, Nonetheless, the present first ever clinical safety guideline for the nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures can help designing conceptual framework for the COVID‐19 safety guidelines in aesthetic practices across the globe.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

7.

Scheme 1.

entering exiting the clinic

Scheme 2.

entering exiting the clinic

Scheme 3.

pre test for the patient access to the clinic

Scheme 4.

informations for the patient

Bertossi D, Mohsahebi A, Philipp‐Dormston WG, et al. Safety guidelines for nonsurgical facial procedures during COVID‐19 outbreak. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1829–1837. 10.1111/jocd.13530

Funding Information

The authors whose names are listed above certify that they have no affiliations with, or involvement in, any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent‐licensing arrangements) or nonfinancial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge, or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dario Bertossi, Email: dario.bertossi@univr.it.

Wolfgang G Philipp‐Dormston, Email: w_dormston@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/events‐as‐they‐happen. Accessed March 29, 2020

- 2. Italian Ministry of Health , Updates on coronavirus infection. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?area=nuovoCoronavirus&id=5351&lingua=italiano&menu=vuoto. Accessed April 22, 2020

- 3. Lai C‐C, Shih T‐P, Ko W‐C, Tang H‐J, Hsueh P‐R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) and coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO . Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Situation Reports. April 1 2020. WHO Situat Rep. 2020;2019(72):1‐19.

- 5. Kapoor KM, Kapoor A. Role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID‐19 infection – a systematic literature review. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.03.24.20042366.1:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rana M, Kundapur R, Maroof A, et al. Way ahead – post Covid‐19 lockdown in India. Indian J Community Heal. 2020;32(2 Special SE‐Advisory):175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gilbert M, Dewatripont M, Muraille E, Platteau J‐P, Goldman M. Preparing for a responsible lockdown exit strategy. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):643‐644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawton G. How do we leave lockdown? New Sci. 2020;246(3277):10‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen W, To HY. To protect healthcare workers better, to save more lives. Anesth Analg. March 2020. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun S, Yu K, Xie Z, Pan X. China empowers Internet hospital to fight against COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020. S0163‐4453(20)30183‐3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Der Sarkissian SA, Kim L, Veness M, Yiasemides E, Sebaratnam DF. Recommendations on dermatologic surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. April. 2020;S0190‐9622(20)30610‐1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher D, Heymann D. Q&A: the novel coronavirus outbreak causing COVID‐19. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang Z, Zhao S, Li Z, et al. The battle against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): emergency management and infection control in a radiology department. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):710‐716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Udwadia ZF, Raju RS. How to protect the protectors: 10 lessons to learn for doctors fighting the COVID‐19 coronavirus. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76(2):128‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emadi S‐N, Abtahi‐Naeini B. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and dermatologists: potential biological hazards of laser surgery in epidemic area. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;198:110598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freeman EE, McMahon DE. Creating dermatology guidelines for Covid‐19: the pitfalls of applying evidence based medicine to an emerging infectious disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):e231‐e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ienca M, Vayena E. On the responsible use of digital data to tackle the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):463‐464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Ning Z, Chen Y, et al. Aerodynamic characteristics and RNA concentration of SARS‐CoV‐2 aerosol in Wuhan Hospitals during COVID‐19 Outbreak. bioRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirk‐Bayley J, Combes J, Sunkaraneni V, Challacombe S.The Use of Povidone Iodine Nasal Spray and Mouthwash During the Current COVID‐19 Pandemic May Reduce Cross Infection and Protect Healthcare Workers (March 28, 2020). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3563092

- 22. U.S. Department of Labor : Occupational Safety and Health Administration . Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID‐19. Saf Heal. 2020.

- 23. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv. January 2020:2020.02.06.20020974. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khurana A, Sharma KA, Bachani S, et al. SFM India oriented guidelines for ultrasound establishments during the COVID 19 pandemic. J Fetal Med. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177‐1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARSCoV‐2 as compared with SARS‐CoV‐1. N Engl J Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Institute of Medicine . The Use and Effectiveness of Powered Air Purifying Respirators in Health Care: Workshop Summary. USA: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stone DN, Deci EL, Ryan RM. Beyond talk: creating autonomous motivation through self‐determination theory. J Gen Manag. 2009;34(3):75‐91. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan Y, Chen H, Chen L, et al. Consensus of Chinese experts on protection of skin and mucous membrane barrier for health‐care workers fighting against coronavirus disease 2019. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10 1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng Y, Lai W. Dermatology staff participate in fight against Covid‐19 in China. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2020;34(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen Y, Pradhan S, Xue S. What are we doing in the dermatology outpatient department amidst the raging of the 2019 novel coronavirus? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmed F, Zviedrite N, Uzicanin A. Effectiveness of workplace social distancing measures in reducing influenza transmission: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qian H, Zheng X. Ventilation control for airborne transmission of human exhaled bio‐aerosols in buildings. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 19):S2295‐S2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministry of Health S . Environmental Cleaning Guidelines for Healthcare Settings (Summary Document) Summary of Recommendations. 2013.

- 36. Geller C, Varbanov M, Duval RE. Human coronaviruses: insights into environmental resistance and its influence on the development of new antiseptic strategies. Viruses. 2012;4(11):3044‐3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rabenau HF, Cinatl J, Morgenstern B, Bauer G, Preiser W, Doerr HW. Stability and inactivation of SARS coronavirus. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2005;194(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities. Bennett & Brachman’s Hospital Infections. 6th edn. 2019;(May). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS‐CoV‐2 as compared with SARS‐CoV‐1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564‐1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(3):246‐251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beck SE, Wright HB, Hargy TM, Larason TC, Linden KG. Action spectra for validation of pathogen disinfection in medium‐pressure ultraviolet (UV) systems. Water Res. 2015;1(70):27‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chew‐Graham CA, May CR, Perry MS. Qualitative research and problems of judgement: lessons from interviewing fellow professionals. Fam Pract. 2002;19(3):285‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Holden JD. Hawthorne effects and research into professional practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7(1):65‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]