Background

Since the first cases were reported in China in December 2019 [1], Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by a novel Coronavirus, now referred to as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has become a pandemic, raising a great deal of concern about control [2]. At the time of preparing this manuscript (17 April 2020), the World Health Organisation reported that the number of confirmed cases had reached almost two million globally, accounting for 123,000 deaths so far [3]. Therefore, cardiovascular care departments worldwide, including nuclear cardiology units, are confronted with facing the COVID-19 biological risk [4]. This editorial aims to gather the key points regarding protection of patients and nuclear cardiology staff against COVID-19.

Patient management

The fast spread of the COVID-19 outbreak led multiple governments to establish a lockdown. Therefore, many nuclear medicine departments, including nuclear cardiology units, were advised to postpone all non-urgent examinations [5], [6]. The use of nuclear cardiology should be approved only for selected cases according to a priority scale (e.g. perfusion single photon emission tomography in symptomatic and high-risk patients or viability scan in the acute or sub-acute phase of myocardial infarction), and the decision to perform the imaging procedure must be discussed with the referring cardiologist. This decision relies on a trade-off between the infection exposure risk for the patient (who is often susceptible to a severe form of COVID-19) and for staff, and the risk associated with delaying or cancelling the diagnostic test.

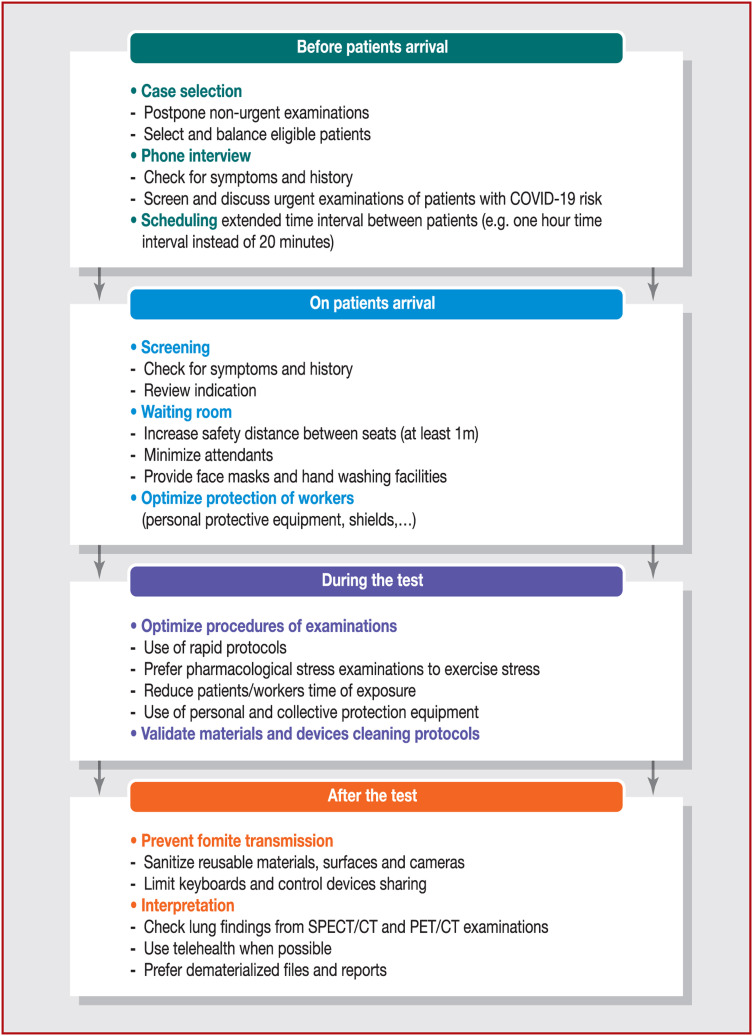

The different steps to consider, from scheduling to interpretation of nuclear cardiology tests, are summarised in Fig. 1 . In practical terms, once an eligible patient arrives at the department, mandatory information about hydroalcoholic friction or hand-washing facilities equipped with soap must be provided, together with access to medical masks (also known as surgical masks); a specific notice outlining good hygiene practice, especially with regard to appropriate gestural behaviour, must also be displayed. An illustrated protocol for effective hand washing and adjustment of masks may be pertinent to prevent surface contamination and aerosols in the waiting area. Signage, (e.g. duct tape on the floor) indicating the security distances that must be respected, should be placed in the waiting room. If necessary, physicians may refer some patients to an appropriate infectious disease consultation. In the case of patients with confirmed COVID-19, the indication to carry out the procedure must be weighed up following a discussion between the nuclear cardiologist and the referring physician. If possible, patients who are COVID-19 positive should be scheduled at the end of the day, to limit their contact with other patients, and the usual biodecontamination protocol should be performed after their scan. If a patient who is COVID-19 positive needs an urgent examination, a 15-minute drying time after all handled areas have been disinfected is necessary before the next patient is taken.

Figure 1.

Implementation of protection for patients and healthcare workers to minimise Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) exposure in nuclear cardiology units. CT: computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography.

Recent data suggest that not only aerosol transmission, but also fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is plausible, as the virus can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours and on surfaces for days [7]; these findings call for rigorous monitoring of hygiene procedures in the unit. Therefore, close collaboration between the nuclear medicine and hygiene departments is critical in each structure. Procedures may vary from one institution to another, but hygiene rules are mainly based on spatial distancing, hydroalcoholic friction, generalised mask wearing and classical biocleaning (SARS-CoV-2 is a fragile enveloped virus) using wet disinfectant wipes on handled areas after each passage.

Protection of nuclear cardiology staff

Management of human resources in the nuclear cardiology unit is key. It is critical to reduce the number of people working at the same time, enabling backup to ensure efficient turnover in case of infection within the team. Importantly, workers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection must not be present in the department. Current guidance recommends a return to work for healthcare personnel with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection, if at least 72 hours have passed since recovery [defined as resolution of fever without the use of fever-reducing medications and improvement in respiratory symptoms (e.g. cough and shortness of breath)] and at least 10 days have passed since the symptoms first appeared [8]. Close management of the team is critical to allow continuity of healthcare, such as turnover of both cardiologists and nuclear medicine physicians.

Personal protective equipment will play a critical role in limiting nosocomial spreading of the virus and protecting healthcare professionals. Usually, healthcare practitioners are advised to use surgical masks or FFP2 respirators (or N95 respirators) depending on the mode of pathogen transmission and/or the type of medical activity. However, in the specific context of the COVID-19 pandemic, given that we need better knowledge about its mode of transmission and the important role of asymptomatic transmission, supplies of personal protective equipment are lacking [9] and access to FFP2 respirators may be restricted to medical staff who practice invasive respiratory procedures in intensive care units (and are therefore the most exposed), the consensus today seems to be clearly in favour of universal masking of both patients and workers. Interestingly, studies have confirmed that the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza in healthcare personnel taking care of outpatients wearing either medical masks or N95 respirators resulted in no significant difference between the two groups [10]. Therefore, the wearing of medical masks should be considered for all nuclear cardiology personnel, including cleaning staff, and patients. Also, working clothes, protective coveralls, hoods, face shields and other protective equipment may be used to optimise protection. However, these materials will have to be cleaned or changed regularly. Practically, personal protective equipment mainly relies on generalised mask wearing (caregiver/caretaker). FFP2 respirators are limited to invasive procedures with risk of aerosols or when the patient cannot wear a mask (the operator then wears an FFP2 respirator and glasses or a face shield). Camera surfaces and non-disposable materials used for patient examinations should be disinfected with the appropriate product after each scan [11].

Effort stress test procedures are not fully compatible with the wearing of masks by patients, and potentially result in exposure to droplet projections; they should be limited in intensity and combined with a vasodilator or, preferably, switched to just a pharmacological stress test, as recommended by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging [5]. Finally, optimisation of nuclear cardiology procedures will often be superimposed with the three principles of external radiological protection (time of exposure, distance from the source and shielding) that are well mastered by nuclear cardiology staff [12]. Hygiene advice from the field included in this paper should be balanced with new insights into managing the pandemic that will be gathered in the near future, particularly SARS-CoV-2 detection in the nose for each patient before any nuclear cardiology examination.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic situation is changing rapidly, and further studies are needed to efficiently manage the protection of patients and healthcare workers. Implementation of a simple and robust hygiene plan based on spatial distancing, frequent hand washing and universal masking of all personnel in nuclear cardiology units is required to prevent further nosocomial spread of the outbreak.

Sources of funding

None.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel Coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedford J., Enria D., Giesecke J., et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 2020. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the Mission briefing on COVID-19 – 16 April. [Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mission-briefing-on-covid-19---16-april-2020 (accessed date: 17th April 2020)] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driggin E., Madhavan M.V., Bikdeli B., et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health-care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skali H., Murthy V.L., Al-Mallah M.H., et al. Guidance and best practices for nuclear cardiology laboratories during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an Information Statement from ASNC and SNMMI. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12350-020-02123-2. [Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12350-020-02123-2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skulstad H., Cosyns B., Popescu B.A., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritisation, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21:592–598. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention . Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/return-to-work.html (accessed 14th May 2020)] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. 2020. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 27 March. [Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---27-march-2020 (accessed date: 28th March 2020)] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radonovich L.J., Jr., Simberkoff M.S., Bessesen M.T., et al. N95 respirators vs. medical masks for preventing influenza among health care personnel: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:824–833. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigne J., Aide N., Peyronnet D., Nganoa C., Agostini D., Barbey P. When nuclear medicine radiological protection meets biological COVID-19 protection. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04806-x. [Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00259-020-04806-x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]