Abstract

Objectives

To compare the clinical and laboratory features of severe acute respiratory syndrome 2003 (SARS) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2 Chinese pediatric cohorts, given that the causative pathogens and are biologically similar.

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study reviewing pediatric patients with SARS (n = 43) and COVID-19 (n = 244) who were admitted to the Princess Margaret Hospital in Hong Kong and Wuhan Children's Hospital in Wuhan, respectively. Demographics, hospital length of stay, and clinical and laboratory features were compared.

Results

Overall, 97.7% of patients with SARS and 85.2% of patients with COVID-19 had epidemiologic associations with known cases. Significantly more patients with SARS developed fever, chills, myalgia, malaise, coryza, sore throat, sputum production, nausea, headache, and dizziness than patients with COVID-19. No patients with SARS were asymptomatic at the time of admission, whereas 29.1% and 20.9% of patients with COVID-19 were asymptomatic on admission and throughout their hospital stay, respectively. More patients with SARS required oxygen supplementation than patients with COVID-19 (18.6 vs 4.7%; P = .004). Only 1.6% of patients with COVID-19 and 2.3% of patients with SARS required mechanical ventilation. Leukopenia (37.2% vs 18.6%; P = .008), lymphopenia (95.4% vs 32.6%; P < .01), and thrombocytopenia (41.9% vs 3.8%; P < .001) were significantly more common in patients with SARS than in patients with COVID-19. The duration between positive and negative nasopharyngeal aspirate and the length in hospital stay were similar in patients with COVID-19, regardless of whether they were asymptomatic or symptomatic, suggesting a similar duration of viral shedding.

Conclusions

Children with COVID-19 were less symptomatic and had more favorable hematologic findings than children with SARS.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS, Chinese, children

Abbreviations: ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CT, Computed tomography; LOS, Length of stay; NPA, Nasopharyngeal aspirate; SARS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Subsequently, more patients with COVID-19 were diagnosed in other parts of Mainland China, nearby regions and countries in Asia, and beyond. It was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.1 The first patient with SARS was reported in Mainland China in 2003, and subsequently other patients with COVID-19 were diagnosed in other parts of the world. Significantly fewer people were affected by SARS-CoV within the 6-month epidemic, and only 8096 cases and 774 deaths were reported worldwide.2 There have been no known reported cases of SARS since 2004.

Both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 belong to the betacoronavirus genus and are phylogenetically related to bat SARS-like coronavirus, but relatively more distantly to Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome-CoV. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 share 79% genetic similarity.3 They also share similar infection pathophysiology in humans, because they both bind to the same human receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), for entry into host cells. However, SARS-CoV-2 has higher transmissibility, with a higher reproductive number of 2.0-2.5 compared with 1.7-1.9 for SARS-CoV.4 Studies from Wuhan describing the clinical characteristics of 171 children with COVID-19 showed that 15.8% of patients in their cohort were asymptomatic carriers, and only 1 patient required intensive care with ventilator support.5 In contrast, previous studies summarizing the clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with SARS showed they were almost all symptomatic.4 A serologic study showed that asymptomatic SARS cases in children was rare.6 Furthermore, compared with other coronavirus infections that cause milder diseases, both SARS and COVID-19 have significantly greater morbidity and mortality.7 Nevertheless, studies providing a direct comparison of clinical and laboratory features between children infected with SARS and COVID-19 are lacking. In this study, we investigated the clinical and laboratory features in 2 representative Chinese pediatric cohorts with SARS and COVID-19. Understanding the differences and similarities in the clinical phenotypes and laboratory measures in pediatric patients with SARS and COVID-19 will guide us in the identification, quarantine, and management of infected children in a timely manner.

Methods

This was a comparative study examining the clinical and laboratory features of Chinese children (aged ≤18 years at admission) with SARS in Hong Kong and COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. In Hong Kong, pediatric patients diagnosed with SARS and admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital from March 1 to April 30, 2003, were included in the study. Princess Margaret Hospital is a key public hospital that served as the major center for managing patients with SARS in Hong Kong at the beginning of the SARS-CoV outbreak in 2003. More than one-third (36%) of pediatric patients with SARS in Hong Kong were admitted to and managed in Princess Margaret Hospital. The case definitions and clinical characteristics have been previously published in a peer-reviewed journal.8 In Wuhan, pediatric patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, as confirmed by nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) specimen using a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test and who were admitted to the Wuhan Children's Hospital between January 21 and March 20, 2020, were included in this study. The Wuhan Children's Hospital is the main center assigned by the central government for treating children diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Wuhan.5 Children in both cohorts were tested if symptomatic or if in contact with a confirmed case of SARS or COVID-19. Those with a positive test were hospitalized regardless of symptoms. Those with SARS or SARS-CoV-2 infection are referred to as SARS or COVID-19 cases, respectively, regardless of symptoms. Hospital records and laboratory results from both SARS and COVID-19 cohorts were retrieved and analyzed. Demographics, clinical symptoms, days between positive and negative NPA, length of stay (LOS) in hospital, need for oxygen and mechanical ventilation, and laboratory tests were compared between the 2 cohorts. The duration between positive and negative NPA was defined as the time between the first SARS-CoV-2 positive NPA specimen and the first of 2 consecutive NPA negative specimens. Asymptomatic patients were defined in Wuhan as no clinical symptoms and no abnormal computed tomography (CT) findings, as all patients with COVID-19 received a CT scan of the thorax before transfer or after admission to the Wuhan Children's Hospital.9 Both patients with COVID-19 and patients with SARS were discharged after resolution of the clinical symptoms and after receiving 2 consecutive negative NPA tests for SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, respectively. Patients with SARS were also mandated to stay in the hospital for 21 days from symptom onset.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR) and analyzed by the independent t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Categorical variables for SARS, symptomatic COVID-19, and asymptomatic COVID-19 groups were expressed as number (%) and analyzed by a χ2 test, Fisher exact test, or ANOVA. Age- and sex-matched references from Chinese children were used for comparing blood measures. A 2-sided α of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Patients with missing data will not be analyzed for the particular variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 19 (IBM, Armonk, New York, NY), Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington), and Statistical Analysis System v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster Institutional Review Board (Reference number: UW 20-292) and the Research Ethics Board of the Wuhan Children's Hospital (Reference number: WHCH 2020022).

Results

Patient Demographics

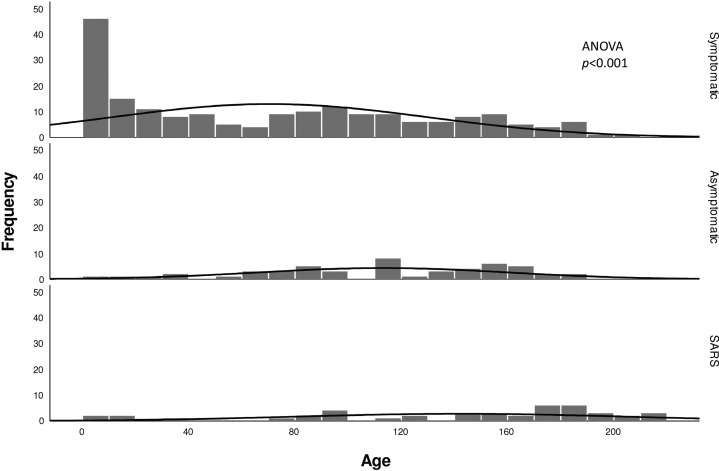

A total of 43 pediatric patients with SARS and 244 pediatric patients with COVID-19 were recruited into the study. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table I . The median age of the COVID-19 cohort was 82 months and the SARS cohort was 160.8 months (Figure 1 ). There were a total of 85 (34.8%) asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 compared with no asymptomatic patients with SARS at presentation (P < .001). Among asymptomatic patients with COVID-19, 94.1% (48/51) had family members with COVID-19 and were identified by screening after family members had been confirmed positive. Among the 85 clinically asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 at presentation, 34 were considered symptomatic by definition after admission. Among them, 26.5% (9/34) developed clinical symptoms including cough, nasal congestion, vomiting, diarrhea, poor feeding. Among the symptomatic patients, 73.5% (25/34) were found to have mild abnormalities on CT imaging, including ground glass opacities and pneumonic changes; only 1 patient had both clinical symptoms and CT abnormalities.

Table I.

Characteristics and symptoms in pediatric patients with COVID-19 and SARS-CoV

| Characteristics | Wuhan COVID-19 2020 (n = 244) |

Hong Kong SARS-CoV 2003 (n = 43) | P value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic (n = 193) | Asymptomatic (n = 51) | P value∗ | |||

| Demographics and epidemiology | |||||

| Age, mo | 67.0 (106) | 116.0 (71) | <.001 | 160.8 (90) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 120 (62.2) | 30 (58.8) | .746 | 20 (46.5) | .0852 |

| Epidemiologic link identified | 160 (82.9) | 48 (94.1) | .047 | 42 (97.7) | .0083 |

| Duration of NPA turning negative, d | 8.2 ± 5.8 | 8.9 ± 5.1 | .434 | – | – |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 13.0 ± 6.0 | 11.4 ± 5.2 | .066 | 20.6 ± 3.6 | <.001 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fever | 99 (51.3) | – | – | 42 (97.7) | <.001 |

| Chills | 2 (1.0) | – | – | 14 (32.6) | <.001 |

| Myalgia | 9 (4.7) | – | – | 16 (37.2) | <.001 |

| Malaise | 9 (6.5) | – | – | 25 (58.1) | <.001 |

| Poor feeding | 8 (4.1) | – | – | 3 (7.0) | .426 |

| Coryza | 24 (12.4) | – | – | 17 (39.5) | <.001 |

| Sore throat | 10 (5.2) | – | – | 7 (16.3) | .019 |

| Cough | 120 (62.2) | – | – | 28 (65.1) | .862 |

| Sputum | 25 (13.0) | – | – | 17 (39.5) | <.001 |

| Diarrhea | 15 (7.8) | – | – | 7 (16.3) | .141 |

| Nausea | 23 (11.9) | – | – | 12 (27.9) | .015 |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (2.1) | – | – | 3 (7.0) | .116 |

| Headache | 10 (5.2) | – | – | 15 (34.9) | <.001 |

| Dizziness | 3 (1.6) | – | – | 5 (11.6) | .006 |

| Supportive care | |||||

| Oxygen supplementation | 9 (4.7) | – | – | 8 (18.6) | .004 |

| Mechanical ventilation support | 3 (1.6) | – | – | 1 (2.3) | .559 |

Data are median (IQR), number (%), or mean ± SD.

Comparison between the COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic groups.

Comparison between the COVID-19 symptomatic and SARS groups.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of patients with COVID-19 and patients with SARS.

Overall, 97.7% of patients with SARS (42/43) and 85.2% of patients with COVID-19 (208/242) had identifiable epidemiologic links in known cases. In the COVID-19 cohort, a 10-month-old boy died of intussusception and multiorgan failure, which has been reported elsewhere.5 No mortality was reported in the SARS cohort. There were no significant differences in the time from positive to negative NPA between the symptomatic and asymptomatic COVID-19 groups (mean of 8.2 days vs 8.9 days; P = .434). There were also no significant differences in the LOS in hospital between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 (mean 13.0 days vs 11.4 days; P = .066), but the LOS in the SARS cohort (all symptomatic) was significantly longer than in the symptomatic COVID-19 cohort (mean 20.6 days vs 12.9 days; P < .001).

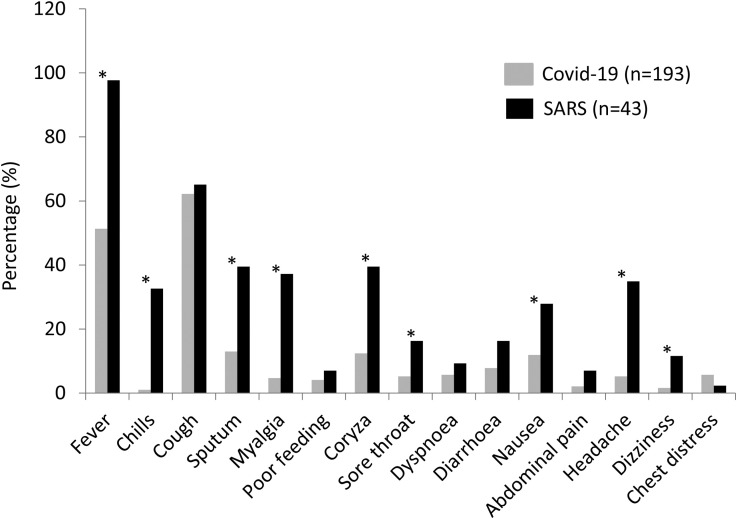

Clinical Symptoms

A comparison of symptoms between the SARS and COVID-19 cohorts are presented in Table I and Figure 2 . Compared with patients with COVID-19, significantly more patients with SARS developed fever (P < .001), chills (P < .001), myalgia (P < .001), malaise (P < .001), coryza (P < .001), sore throat (P = .019), sputum production (P < .001), nausea (P = .015), headache (P < .001), and dizziness (P = .006). Almost all patients with SARS developed fever, compared with only 51.3% of patients with COVID-19. Cough symptoms occurred similarly in both cohorts. More patients with SARS required oxygen supplementation than patients with COVID-19 (18.6% vs 4.7%; P = .004), whereas only 1.6% and 2.3% of patients with COVID-19 and patients with SARS required mechanical ventilatory support, respectively.

Figure 2.

COVID-19 and SARS symptoms comparison. ∗P < .05.

Laboratory Test Results

Laboratory testing results for SARS and symptomatic patients with COVID-19 are presented in Table II . Patients with SARS had a significantly lower total white blood cell count (P = .043), lymphocyte count (P < .001), and platelet (P < .001) count, and lower albumin (P < .001), higher globulin (P < .001), higher alanine aminotransferase (P = .01), and lower d-dimer (P < .001) levels. We further explored the number of children with leukopenia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia using age- and sex-matched reference ranges for Chinese and Asian children.10, 11, 12 Leukopenia (37.2% vs 18.6%; P = .008), lymphopenia (95.4% vs 32.6%; P < .01), and thrombocytopenia (41.9% vs 3.8%; P < .001) were significantly more common in patients with SARS than in patients with COVID-19. The laboratory test results for asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 were normal.

Table II.

Laboratory test results in pediatric patients with COVID-19 (symptomatic cases) and SARS

| Laboratory tests | Wuhan, COVID-19 2020 (n = 193) |

Hong Kong, SARS-CoV 2003 (n = 43) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Median | SD/IQR | Range | No. | Mean/Median | SD/IQR | Range | No. | P value | |

| White cell count, ×109/L | 7.1 | 2.7 | 0.75-13.8 | 183 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 2.2-23.2 | 43 | .043 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.4 | 1.5 | 6.7-18.3 | 183 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 7.6-131.0 | 43 | .193 |

| Platelet, ×109/L | 291.5 | 128.8 | 14.0-751.0 | 183 | 212.0 | 76.5 | 168.0-580.0 | 43 | <.001∗ |

| Lymphocyte, ×109/L | 3.4 | 1.9 | 0.2-11.7 | 184 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 0.6-9.4 | 43 | <.001 |

| Albumin, g/L | 45.0 | 3.5 | 34.7-55.9 | 192 | 43.4 | 6.5 | 29.0-52.0 | 40 | <.001 |

| Globulin, g/L | 22.8 | 5.0 | 11.1-32.2 | 187 | 34.0 | 5.5 | 23.0-44.0 | 40 | <.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 16.0 | 17.0 | 4.0-596.0 | 193 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 12.0-80.0 | 41 | .010∗ |

| LDH, U/L | 239.0 | 94.2 | 142.0-656.0 | 189 | 262.0 | 168.5 | 147.0-1143.0 | 36 | .285∗ |

| DD, mg/L FEU | 1.2 | 8.9 | 0.01-100.8 | 140 | −0.11 | 0.18 | −0.2 to 0.2 | 11 | <.001∗ |

| APTT, sec | 34.3 | 28.6 | 23.4-353.0 | 169 | 32.0 | 4.2 | 25.9-37.3 | 29 | .827 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; DD, d-dimer; FEU, fibrinogen equivalent units; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Mann-Whitney U test, results presented as median (IQR).

Discussion

In our study of Chinese children infected with COVID-19 and SARS in representative pediatric cohorts from Wuhan and Hong Kong, patients with COVID-19 experienced fewer symptoms than patients with SARS. Almost all patients with SARS presented with fever compared with only one-half of patients with COVID-19, which suggests screening by body temperature will potentially miss one-half of the children infected with COVID-19. Although a similar percentage of patients in both cohorts had a cough, significantly more patients with SARS had other symptoms, including fever and respiratory difficulties.8 , 13 A study comparing the replication, cell tropism, and immune activation profile of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections in human lung tissue showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection generated 3.2 times more virus particles, yet induced significantly less type I, II, and III interferons and other proinflammatory cytokines, which might explain the relatively milder phenotype in COVID-19.14

Only a few children in both cohorts required oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation. In contrast with adult patients, our results echo that children infected by either SARS-CoV-2 or SARS-CoV had a good prognosis.15 , 16 Indeed, studies have shown that a higher percentage of older adults with COVID-19 develop complications, including pneumonia, acute myocardial injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, with an overall mortality of ≤11% in some populations.17 Similar observations were reported during the SARS-CoV epidemic in 2003, which had 7% and 17% mortality in Mainland China and Hong Kong, respectively.2 The majority of the patients who died from SARS and COVID-19 were older patients with underlying chronic illnesses or who were immunocompromised.18 A study comparing published data in the literature also concurred with our findings that children with SARS and COVID-19 infection had favorable outcomes.19 One possible explanation why children are less affected by both SARS and COVID-19 is the different expressions of ACE2 in children and adults. The ACE2 receptor is crucial for both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 to enter into host cells.20 It has been demonstrated that ACE2 expression can influence the infectivity of SARS-CoV in vitro.21 Nevertheless, studies demonstrating age variation of ACE2 expression currently are lacking.

Our study also showed there were significantly more asymptomatic carriers in the pediatric group with COVID-19; there were none in the pediatric SARS group. This finding was consistent with studies in adults with SARS, which found only a few asymptomatic adults or healthcare workers who tested antibody positive after the epidemic or had only mild and self-limiting symptoms.22 , 23 To the contrary, asymptomatic COVID-19 infections were reported to be common among adults and younger adults without comorbidities.24 Asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 may be one of the key factors leading to the pandemic.25 In our study, the average time to achieve a negative NPA and hospital LOS were similar for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with COVID-19, which indicates that clearance of COVID-19 virus may be similar for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. A difficulty in concluding this is that dating of the first specimen at the onset in symptomatic patients cannot be replicated in asymptomatic patients. Although we found the LOS in hospital for the SARS cohort was significantly longer than that for the symptomatic COVID-19 cohort (20.6 days vs 11.4 days; P < .001), a difference in the isolation policy between the 2 outbreaks likely confounded this observation. In the SARS outbreak in 2003, the mandatory hospitalization for patients was 21 days from symptoms onset in addition to a negative NPA and resolution of symptoms. More important, our study also revealed that 35.6% of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic on admission and 14.9% subsequently became symptomatic. These asymptomatic patients are still carriers of the virus and have the potential to spread the disease to others, leading to further burdens on public health systems. Public health measures such as the universal use of facemasks, social distancing, early quarantine, and identification and tracing of asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 have already been widely adopted in places with less severe outbreak such as Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Studies have shown that frequent and proper use of facemasks in public areas was associated with a 60% lower risk of contracting SARS-CoV compared with infrequent use during the SARS outbreak in 2003.26 Repeated reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction testing for SARS-CoV-2 should also be performed in those highly suspected of infection where there is an initial possible false-negative result. Given the evidence of a significant proportion of asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers and experience from Asia, strict preventive measures should be enacted to control the spread of COVID-19.

We found that the COVID-19 cohort had more favorable hematologic and biochemical findings, with fewer patients with COVID-19 having abnormal test results compared with patients with SARS. The mean total white blood cell, lymphocyte, and median platelet counts in patients with SARS were all significantly lower than in patients with COVID-19. Potential mechanisms include direct infection of hematopoietic progenitor cells via cell surface CD13 or CD66a that possibly induces growth inhibition and apoptosis.27 Although the COVID-19 cohort was significantly younger than the SARS cohort, significantly fewer children in the COVID-19 cohort had hematologic abnormalities when using age- and sex-matched references. Lymphopenia was observed during the early phase of the SARS epidemic, predominantly CD4+ and CD8+ lymphopenia, and adult patients with SARS-CoV who were clinically more severe or died had significantly more severe CD4+ and CD8+ lymphopenia.28 , 29 In COVID-19 infection, the degree of lymphopenia was reported to be a prognostic indicator for older patients.30 The significantly lower proportion of pediatric patients with COVID-19 with lymphopenia may explain the milder phenotype compared with the SARS group.

This study had several limitations. First, this was retrospective observational study design, which may have potential recall or sampling bias. Nevertheless, the majority of children with COVID-19 under the age of 18 years in Wuhan were admitted to the Wuhan Children's Hospital, and the majority of pediatric patients with SARS in Hong Kong were admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital. Wuhan and Hong Kong were among the most seriously affected cities in the COVID-19 and SARS outbreaks, respectively. Therefore, they are representative pediatric cohorts for these 2 infections. Second, not all family contacts of SARS cases were tested in 2003. Nevertheless, in the study conducted by Lee et al, only 0.57% of asymptomatic children from the Amoy Garden were positive for SARS-CoV antibody.6 None of the 14 asymptomatic children who had contacts with patients with SARS were seropositive.6 The Amoy Garden was one of the housing estates in Hong Kong with major community outbreak. It was also where the majority of the SARS-infected children in this cohort were recruited. Therefore, despite the lack of close contact screening in 2003, SARS asymptomatic carriage was considered to be rare. Third, younger patients with COVID-19 may not be able to describe their subjective symptoms, such as anosmia, which is considered a novel symptom of COVID-19, which may lead to under-reporting of these symptoms.31 Fourth, CT and other radiologic findings were not reported in details as the majority of the patients with SARS did not have a CT scan performed and therefore was considered out of the scope of this manuscript. Radiologic findings of some of the patients from Wuhan's Children Hospital have been reported elsewhere.9 Fifth, a recent phylogenetic network study showed that the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant (type B) in East Asia is genetically different from the variants in Europe and America (types A and C). Whether such differences lead to different clinical characteristics between Asia and the West remains uncertain, and one must be cautious in extrapolating clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in Asia to other geographic areas.32 Finally, we did not observe any children developing Kawasaki-like hyperinflammatory shock that was reported in European children with COVID-19 in our Chinese cohort.33 , 34 Future studies combining and comparing data from international clinical centers will be meaningful to examine the demographics and clinical spectrum of pediatric patients with COVID-19 on a global perspective, and to further identify the risk factors for these severe diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff members of the Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, the Princess Margaret Hospital, and Wuhan Children's Hospital for their dedication in caring for sick children, which can be a very difficult time for both patients and their families.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2.Summary table of SARS cases by country, 1 November 2002 - 7 August 2003: World Health Organization; 2003. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/country2003_08_15.pdf?ua=1

- 3.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrosillo N., Viceconte G., Ergonul O., Ippolito G., Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu X., Zhang L., Du H., Zhang J., Li Y.Y., Qu J. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee P.P., Wong W.H., Leung G.M., Chiu S.S., Chan K.H., Peiris J.S. Risk-stratified seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus among children in Hong Kong. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1156–e1162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau S.K.P., Woo P.C.Y., Yip C.C.Y., Tse H., Tsoi H.W., Cheng V.C. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2063–2071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02614-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung C.-w., Kwan Y.-w., Ko P.-w., Chiu S.S., Loung P.Y., Fong N.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome among children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e535. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma H., Hu J., Tian J., Zhou X., Li H., Laws M.T. A single-center, retrospective study of COVID-19 features in children: a descriptive investigation. BMC Med. 2020;18:123. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding Y., Zhou L., Xia Y., Wang W., Wang Y., Li L. Reference values for peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets of healthy children in China. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:970–973.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Ding Y., Zhang Y., Xing J., Dai Y., Yuan E. Age- and sex-specific reference intervals for hematologic analytes in Chinese children. Int J Lab Hematol. 2019;41:331–337. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nah E.H., Kim S., Cho S., Cho H.I. Complete blood count reference intervals and patterns of changes across pediatric, adult, and geriatric ages in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2018;38:503–511. doi: 10.3343/alm.2018.38.6.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockman L.J., Massoudi M.S., Helfand R., Erdman D., Siwek A.M., Anderson L.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:68–74. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000247136.28950.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu H., Chan J.F.-W., Wang Y., Yuen T.T., Chai Y., Hou Y. Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in human lungs: an ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 9 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa410. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu W.K., Cheung P.C., Ng K.L., Ip P.L., Sugunan V.K., Luk D.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome in children: experience in a regional hospital in Hong Kong. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4:279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000077079.42302.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajgor D.D., Lee M.H., Archuleta S., Bagdasarian N., Quek S.C. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:776–777. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan R.E., Adab P., Cheng K.K. Covid-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S., Malhotra N., Gupta N., Agrawal S., Ish P. The curious case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children. J Pediatr. 2020;222:258–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J., Huang Z., Lin L., Lv J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular disease: a viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016219. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia H.P., Look D.C., Shi L., Hickey M., Pewe L., Netland J. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2005;79:14614–14621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Che X.-y., Di B., Zhao G.-p., Alizadeh B.Z., Wijmenga C., Witt M. A patient with asymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and antigenemia from the 2003–2004 community outbreak of SARS in Guangzhou, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:e1–e5. doi: 10.1086/504943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwan M.Y., Chan W.M., Ko P.W., Leung C.W., Chiu M.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome can be mild in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:1172–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He G., Sun W., Fang P., Huang J., Gamber M., Cai J. The clinical feature of silent infections of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in Wenzhou. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr 10 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25861. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., Tian F., Jin D.Y., Chen L. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan K.H., Yuen K.-Y. COVID-19 epidemic: disentangling the re-emerging controversy about medical facemasks from an epidemiological perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Mar 31 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa044. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang M., Li C.K., Li K., Hon K.L., Ng M.H., Chan P.K. Hematological findings in SARS patients and possible mechanisms (review) Int J Mol Med. 2004;14:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panesar N.S. Lymphopenia in SARS. Lancet. 2003;361:1985. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13557-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui W., Fan Y., Wu W., Zhang F., Wang J.Y., Ni A.P. Expression of lymphocytes and lymphocyte subsets in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:857–859. doi: 10.1086/378587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan L., Wang Q., Zhang D., Ding J., Huang Q., Tang Y.Q. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:33. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gane S.B., Kelly C., Hopkins C. Isolated sudden onset anosmia in COVID-19 infection. A novel syndrome? Rhinology. 2020;58:229–301. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forster P., Forster L., Renfrew C., Forster M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:9241–9243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004999117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riphagen S., Gomez X., Gonzalez-Martinez C., Wilkinson N., Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones V.G., Mills M., Suarez D., Hogan C.A., Yeh D., Segal J.B. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:537–540. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]