Abstract

Robotic surgery has been used for a long time; it is earning space and its use is expanding in daily medical practice in several surgical specialties, with advantages over traditional surgical methods. This Technical Note presents an endoscopic robotic posterior shoulder approach that allows the surgeon to perform latissimus dorsi transfer endoscopically. This Technical Note describes the use of the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) for transfers related to rotator cuff tears.

Robotic surgery has been used for a long time1,2; it is earning space and its use is expanding in daily medical practice in several surgical specialties, with advantages over traditional surgical methods.3,4 Within orthopaedics, we highlight the use of robotics in brachial plexus treatment5,6 and neurologic releases.7, 8, 9

The association of robotic technology with endoscopy further allowed a faster recovery for the patient with many applications, with a shorter time of hospitalization and minimally invasive approach.10 The advantages of this method include movement accuracy, high-resolution imaging with 3-dimensional vision, gas infusion rather than saline solution (better visualization), filtering of the surgeon's tremor when manipulating objects, movement scaling, and hands-free camera manipulation.11, 12, 13, 14 In addition, in the future, there is the possibility of remote surgery (telesurgery) in which a surgical team can treat a patient far away1,2 or a surgical team may be composed of professionals located in different cities or countries, treating the same patient simultaneously.

Some shoulder pathologies that require a posterior shoulder approach may need aggressive and traumatic exposure with extensive manipulation of soft tissues. The possibility of using a minimally invasive approach can potentially be important for both the timing of rehabilitation and avoidance of local soft-tissue adhesions. In addition, when performing a large posterior open approach, one needs to use tensioned retractors to properly maintain the surgical field. The use of these tensioned retractors can eventually damage the deeper muscle layer as well as other neurovascular structures.15,16

Minimally invasive procedures have shown a decrease in adhesions, avoiding reoperation and physical therapy over a long period. Indeed, this advantage makes these procedures cost-effective.10

Literature regarding robotic assisted orthopedic surgery is scarce, as opposed to other surgical specialties.17, 18, 19 The use of robotic-assisted surgery for better identification of the quadrangular space of the shoulder, identification of the axillary and radial nerves, and better identification of the latissimus dorsi muscle was described previously in a cadaveric trial on shoulder surgery.20

The visualization and partial manipulation of the latissimus dorsi muscle have already been reported to aid the transportation of the muscular pedicle, with a technique that we used as a reference for our study.19 Axillary nerve identification has also been described,9 making a contribution to our study and confirming the viability of the method. Regarding bleeding, studies in live patients have shown that air insufflation was effective at avoiding it.8 This Technical Note is based on a previous cadaveric trial20 and aims to present the use of the da Vinci robot for transfers of the latissimus dorsi tendon to the humeral head; we have performed this technique to treat massive rotator cuff tears in 4 live patients.

Indications, Preoperative Evaluation, and Imaging

This procedure has the same indications as traditional open transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon: patients with massive rotator cuff tears with poor biological characteristics of the tendon. The ideal surgical indications are grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration according to the Goutallier classification with retraction of more than 4 cm in a patient younger than 60 years presenting with a functional subscapularis tendon. The patient will present with pain, and shoulder elevation and abduction will be difficult or impossible to perform. The younger the patient is, the better the results tend to be.

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed in the ventral decubitus position; the arm is maintained in a position similar to 90° of elevation. The inferior border of the latissimus dorsi can be localized by palpation. A drawing of the muscle is made on the skin based on its inferior border and its known anatomy. The central line of the latissimus dorsi is also drawn. A 1-cm incision is made in the skin, 10 to 15 cm from the axilla, to establish the central portal. Two other portals are made 5 to 7 cm perpendicular medial and lateral to the central line. These portals are located 7 to 10 cm from the axilla. The central portal is used to insert the optics, and through the other 2 portals, the robotic hands are introduced to access the muscular fascia, where a cavity is formed through blunt dissection. This space is made for triangulation as an initial working cavity once there are no natural cavities in this region.

A trocar and cannula are introduced into each incision in a common direction in the cavity the surgeon created (Fig 1). The camera of the da Vinci SI or Xi robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA), with an optic of 30° (Fig 2), is introduced in the first portal on the trapezius.

Fig 1.

Patient in ventral decubitus position. Right shoulder and thorax. (A, B) Robotic hand trocars. (C) Optics trocar. (D) Shoulder. (E) Robotic exterior hand. (F) Robotic exterior hand for optics.

Fig 2.

A robotic optic of 30° with 2 cameras allows a stereoscopic view.

Carbon dioxide is inflated at a constant pressure of 8 to 14 mm Hg through the chamber portal into the working cavity, stretching the soft tissues and opening the cavity. The robotic arms use Cadiere Forceps (8 mm; Intuitive Surgical) and Hot Shears Monopolar Curved Scissors (8 mm; Intuitive Surgical).

The first objective is to clean the area around the camera so that the best dissection and identification of the initial working cavity are achieved. After this first stage, we search for the superior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle and its division with the teres major. Dissection using this muscular plane is performed until its entrance deep into the medial border of the long head of the triceps (Fig 3).

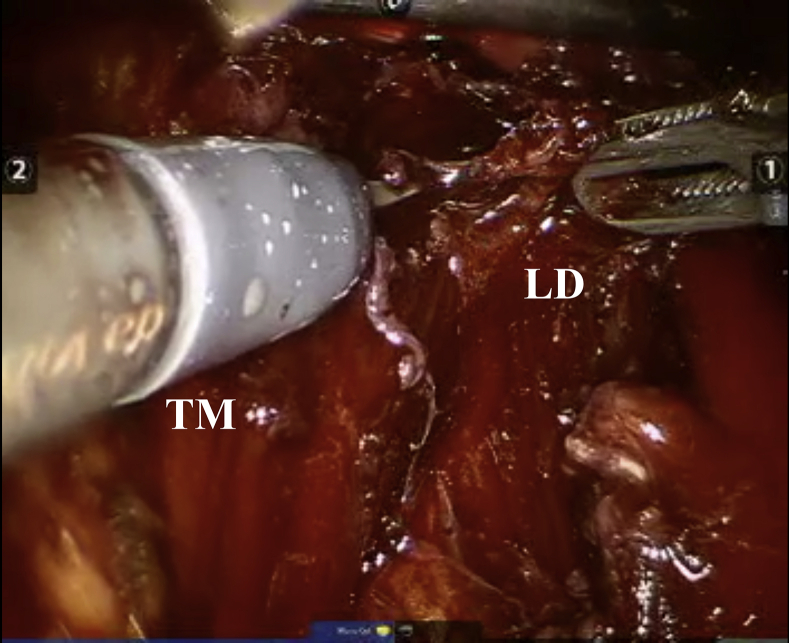

Fig 3.

Optics are placed in the central portal. (LD, latissimus dorsi; TM, teres major.)

The latissimus is released and separated from the teres major (Fig 4); the radial nerve is just below the latissimus, and it is possible to visualize it but not required (Fig 5). Care must be taken to avoid damaging the neurovascular pedicle. A No. 0 Vicryl (J318; Johnson & Johnson, São Paulo, Brazil) is inserted by the cephalic robotic hand’s portal. The latissimus dorsi tendon is sutured by using Cadiere and DeBakey Forceps (Intuitive Surgical) (Fig 6, Video 1). The sutured tendon is pulled out of the body through the central portal of the optics using a gastric forceps.

Fig 4.

With optics within the central portal, the latissimus dorsi (LD) is released. (TM, teres major.)

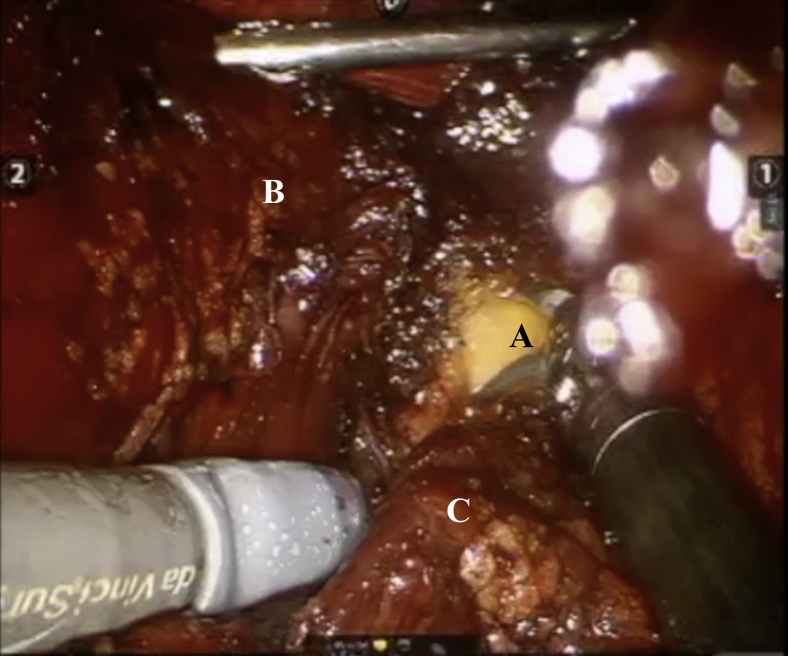

Fig 5.

Optics within central portal showing radial nerve (A), teres major insertion (B), and retracted latissimus dorsi (C).

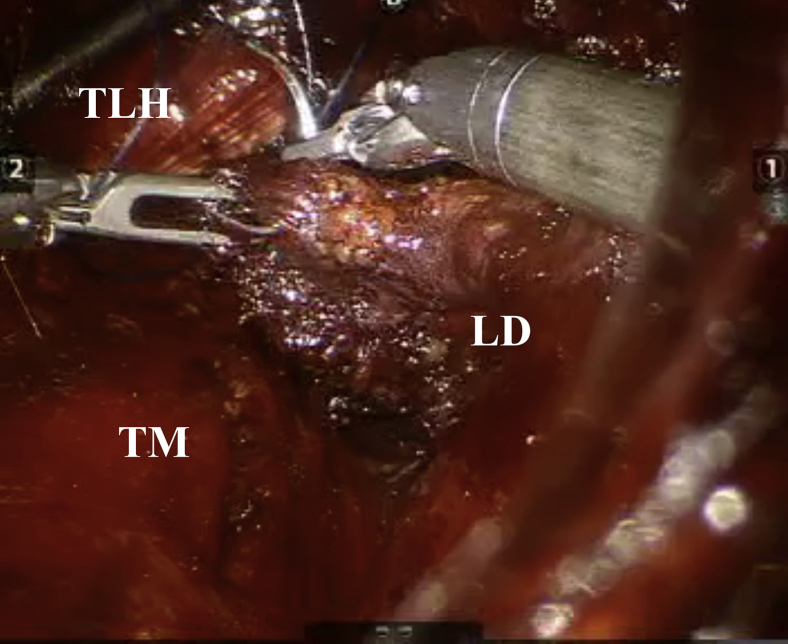

Fig 6.

Optics within central portal showing latissimus dorsi (LD), long head of triceps (TLH), and teres major (TM).

A small 3- to 5-cm incision is made on the lateral deltoid, and by use of a finger, dissection of the subdeltoid space is performed until the cavity created by the robot is reached. A long gastric grasper is inserted through the cephalic robotic hand’s portal until it reaches the subdeltoid space. A guide polyester No. 5 wire is passed by using this grasper, leaving the optics portal (Fig 7).

Fig 7.

The patient is in the ventral decubitus position; the shoulder and scapular area are exposed. (A) Polyester guidewire through deltoid approach. (B) Gastric forceps. (C) Wires where latissimus dorsi was sutured. (D) Polyester guidewire exit.

The humeral head is drilled, and 2 anchors are inserted. The anchor wires are passed, through the deltoid approach, to the optics portal using the No. 5 polyester wire as a guide. The tendon is sutured to the anchor wires using Krackow stitches (Fig 8) and is passed to the subacromial space pulled by the anchor wires, and standard tendon-to-bone suturing is performed. More anchors and sutures can be placed after the tendon lies on the humerus’ greater tuberosity. The portals and deltoid lateral approach are sutured.

Fig 8.

The patient is in the ventral decubitus position; the shoulder and scapular area are exposed. (A) The latissimus dorsi is sutured with suture anchor wires. (B) The other parts of the suture anchor wires are shown; these will pull the tendon to the humeral head.

Rehabilitation

A sling is used for 5 weeks. Pendular movements and passive elevation until 90° are allowed 2 weeks after surgery. After this period, active exercises with isometric external rotation and elevation begin. Two weeks thereafter, isokinetic and proprioception movements begin. Scapular retraction and shoulder extension need to be stimulated in the initial movements, once the latissimus dorsi can also be activated during these movements. Better evolution is present in patients with better active movements before surgery.

Pearls and pitfalls of the described technique are summarized in Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Pearls and Pitfalls

| Pearls and Pitfalls | |

| Robot docking | The da Vinci robot is designed for abdominal exploration; the robot will need to be cephalic with the optics pointed to the central line drawn on the patient’s skin. |

| Movements and subcutaneous dissection | The movements in robotic surgery are different from those in regular endoscopy. Subcutaneous can be better dissected by using horizontal movements of both robotic hands, as usual in robotic surgery, just above the superior portion of the latissimus dorsi and teres major. |

| Triceps tendon | The triceps tendon tends to be close to the working space; the assistant surgeon within the surgical field can insert the aspirator through the triceps to aspirate blood and help the surgeon open the working space. The best location is chosen by an endoscopic view with a needle. |

| Radial nerve | The radial nerve is just a few centimeters under the latissimus dorsi; anatomic knowledge of this area and training on a cadaveric model are strongly recommended to avoid neurologic complications. |

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages Comparing Robotic, Arthroscopic, and Open Surgical Procedures for Latissimus Dorsi Transfer

| Robotic | Arthroscopic | Open | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scarring | Low | Intermediate | High |

| Tendon visualization | Good | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Movement precision | High | Low | Intermediate |

| Surgical time | Longer | Intermediate | Faster |

| Cost | Intermediate | More Expensive | Less Expensive |

| Minimal invasiveness | Less Invasive | Intermediate | Open |

Discussion

Traditional approaches for the latissimus dorsi are wide, requiring large posterior incisions with cosmetic and scar-formation implications. Previous cadaveric and live-patient studies were used to establish the principles for the robotic latissimus dorsi transfer presented in this Technical Note. We aim to present a surgical technique that can be improved on and can even be used for other orthopaedic applications with the future introduction of robots, robotic arms, and smaller optics.

Few studies have assessed the latissimus dorsi using the aid of robotics; all of them accessed the muscle and the origin of the latissimus for free flaps.17, 18, 19, 20 We describe the first in vivo robotic-assisted shoulder surgical procedure performed for transfer of the latissimus dorsi insertion to improve function after a rotator cuff tear. We previously robotically identified the tendon, neurovascular structures, and quadrangular space in cadaveric trials in other trials; thus, the surgical viability and safety of the procedure were previously examined.9,20 In addition, other robotic orthopaedic applications in live patients have shown the effectiveness of air insufflation in achieving better bleeding control.8

We have shown the viability of the introduction of robotics in shoulder surgery in the hope of encouraging further studies in the area. The limitations of this technique are the cost of the robot, robotic hands, and scissors. The necessity for specific training on robotic surgery, which is currently costly and not available in many hospitals, can also limit its current use. The surgical time is currently longer than that of the open procedure; however, this situation tends to improve in time.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: J.C.G. receives personal fees as a Latin America consultant for Zimmer-Biomet and a consultant for Razek, outside the submitted work. E.F.C. receives personal fees as a consultant for Razek, outside the submitted work. M.d.P.R. receives personal fees as a consultant for Razek and Smith & Nephew, outside the submitted work. M.B.D.M. receives personal fees as a consultant for Razek, outside the submitted work. M.E.K. receives personal fees as a consultant for Razek, outside the submitted work. Á.d.M.C. receives personal fees as a consultant for Razek, outside the submitted work. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Robotic transfer of latissimus dorsi tendon. Portals are created 10 to 15 cm from the latissimus dorsi insertion: 1 central, 1 superior, and 1 inferior. Because no natural cavities are present in this area, one can gently create a subcutaneous cavity. The optics trocar is the central portal; the superior and inferior portals are dedicated to the robotic hands. An external view of the initial subcutaneous and muscular dissection is shown. The surgical site is shown as presented by the robot but in 3 dimensions. After a wide dissection, the teres major on the left is separated from the latissimus dorsi on the right. The tendon is cut from its humeral insertion. The latissimus is mobilized and separated from the teres major. Care must be taken because, as can be seen, the radial nerve lies just under the tendon. Knowing where the nerve is makes it easier to release the muscular part of the latissimus dorsi. The released tendon is sutured. The needle and the wire pass through the optics portal. The deltoid approach is created, and a polyester guidewire is inserted from the subdeltoid to the optics portal. Anchors are inserted in the humeral head through the same deltoid approach, and their wires are passed to the optics portal by use of the polyester guidewire. The wires of the suture anchors are sutured on the tendon, and the tendon is pulled through the cavity until the subdeltoid space is reached and the final fixation in bone is achieved.

References

- 1.Ballantyne G.H., Moll F. The da Vinci telerobotic surgical system: The virtual operative field and telepresence surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavoussi L.R., Moore R.G., Partin A.W., Bender J.S., Zenilman M.E., Satava R.M. Telerobotic assisted laparoscopic surgery: Initial laboratory and clinical experience. Urology. 1994;44:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldani A., Bellora P., Monni M., Amato B., Gentilli S. Colorectal surgery in elderly patients: Our experience with DaVinci Xi system. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0670-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallotta V., Cicero C., Conte C. Robotic versus laparoscopic staging for early ovarian cancer: A case matched control study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani G., Liverneaux P.A., Garcia J.C., Berner S.H., Bednar M.S., Mohr C.J. Endoscopic exploration and repair of brachial plexus with telerobotic manipulation: A cadaver trial. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:659–664. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.JNS10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia J.C., Lebailly F., Mantovani G., Mendonça L.A., Garcia J.M., Liverneaux P.A. Telerobotic manipulation of the brachial plexus. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28:491–494. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1313761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia J.C., Mantovani G., Gouzou S., Liverneaux P. Telerobotic anterior translocation of the ulnar nerve. J Robot Surg. 2011;5:153–156. doi: 10.1007/s11701-010-0226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia J.C., Montero E.F.S. Endoscopic robotic decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porto de Melo P.M., Garcia J.C., Montero E.F.S. Feasibility of an endoscopic approach to the axillary nerve and the nerve to the long head of the triceps brachii with the help of the Da Vinci robot. Chir Main. 2013;32:206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan J.A., Thornton B.A., Peacock J.C. Does robotic technology make minimally invasive cardiac surgery too expensive? A hospital cost analysis of robotic and conventional techniques. J Card Surg. 2005;20:246–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2005.200385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrn J.C., Schluender S., Divino C.M. Three-dimensional imaging improves surgical performance for both novice and experienced operators using the da Vinci robot system. Am J Surg. 2007;193:519–522. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solis M. New frontiers in robotic surgery: The latest high-tech surgical tools allow for superhuman sensing and more. IEEE Pulse. 2016;7:51–55. doi: 10.1109/MPUL.2016.2606470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willems J.I.P., Shin A.M., Shin D.M., Bishop A.T., Shin A.Y. A comparison of robotically assisted microsurgery versus manual microsurgery in challenging situations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1317–1324. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shademan A., Decker R.S., Opfermann J.D., Leonard S.K., Axel K., Peter C.W. Supervised autonomous robotic soft tissue surgery. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:337ra64. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijdicks C.A., Armitage B.M., Anavian J., Schroder L.K., Cole P.A. Vulnerable neurovasculature with a posterior approach to the scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2011–2017. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalmers P.N., Van Thiel G.S., Trenhaile S.W. Surgical exposures of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:250–258. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selber J.C., Baumann D.P., Holsinger F.C. Robotic latissimus dorsi muscle harvest: A case series. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824ecc0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung J.-H., You H.J., Kim H.S., Lee B.I., Park S.H., Yoon E.S. A novel technique for robot assisted latissimus dorsi flap harvest. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichihara S., Bodin F., Pedersen J.C. Robotically assisted harvest of the latissimus dorsi muscle: A cadaver feasibility study and clinical test case. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2016;35:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia J.C., Gomes R.V.F., Kozonara M.E., Steffen A.M. Posterior endoscopy of the shoulder with the aid of the Da Vinci SI robot—A cadaveric feasibility study. Acta Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;2:36–39. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Robotic transfer of latissimus dorsi tendon. Portals are created 10 to 15 cm from the latissimus dorsi insertion: 1 central, 1 superior, and 1 inferior. Because no natural cavities are present in this area, one can gently create a subcutaneous cavity. The optics trocar is the central portal; the superior and inferior portals are dedicated to the robotic hands. An external view of the initial subcutaneous and muscular dissection is shown. The surgical site is shown as presented by the robot but in 3 dimensions. After a wide dissection, the teres major on the left is separated from the latissimus dorsi on the right. The tendon is cut from its humeral insertion. The latissimus is mobilized and separated from the teres major. Care must be taken because, as can be seen, the radial nerve lies just under the tendon. Knowing where the nerve is makes it easier to release the muscular part of the latissimus dorsi. The released tendon is sutured. The needle and the wire pass through the optics portal. The deltoid approach is created, and a polyester guidewire is inserted from the subdeltoid to the optics portal. Anchors are inserted in the humeral head through the same deltoid approach, and their wires are passed to the optics portal by use of the polyester guidewire. The wires of the suture anchors are sutured on the tendon, and the tendon is pulled through the cavity until the subdeltoid space is reached and the final fixation in bone is achieved.