Key Points

Question

Can ursodeoxycholic acid administration prevent gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 521 adults, the use of 300 mg or 600 mg of ursodeoxycholic acid, compared with placebo, resulted in a significantly decreased proportion of patients developing gallstones within 12 months after gastrectomy (5.3% in the 300-mg group, 4.3% in the 600-mg group, and 16.7% in the placebo group).

Meaning

Ursodeoxycholic acid administration may prevent gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer.

Abstract

Importance

The incidence of gallstones has been reported to increase after gastrectomy. However, few studies have been conducted on the prevention of gallstone formation in patients who have undergone gastrectomy.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in preventing gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The PEGASUS-D study (Efficacy and Safety of DWJ1319 in the Prevention of Gallstone Formation after Gastrectomy in Patient with Gastric Cancer: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted at 12 institutions in the Republic of Korea. Adults (aged ≥19 years) with a diagnosis of gastric cancer who underwent total, distal, or proximal gastrectomy were enrolled between May 26, 2015, and January 9, 2017; follow-up ended January 8, 2018. Efficacy was evaluated by both the full analysis set, based on the intention-to-treat principle, and the per-protocol set; full analysis set findings were interpreted as the main results.

Interventions

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to receive 300 mg of UDCA, 600 mg of UDCA, or placebo at a ratio of 1:1:1. Ursodeoxycholic acid and placebo were administered daily for 52 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Gallstone formation was assessed with abdominal ultrasonography every 3 months for 12 months. Randomization and allocation to trial groups were carried out by an interactive web-response system. The primary end point was the proportion of patients developing gallstones within 12 months after gastrectomy.

Results

A total of 521 patients (175 received 300 mg of UDCA, 178 received 600 mg of UDCA, and 168 received placebo) were randomized. The full analysis set included 465 patients (311 men; median age, 56.0 years [interquartile range, 48.0-64.0 years]), with 151 patients in the 300-mg group, 164 patients in the 600-mg group, and 150 patients in the placebo group. The proportion of patients developing gallstones within 12 months after gastrectomy was 8 of 151 (5.3%) in the 300-mg group, 7 of 164 (4.3%) in the 600-mg group, and 25 of 150 (16.7%) in the placebo group. Compared with the placebo group, odds ratios for gallstone formation were 0.27 (95% CI, 0.12-0.62; P = .002) in the 300-mg group and 0.20 (95% CI, 0.08-0.50; P < .001) in the 600-mg group. No significant adverse drug reactions were detected among the enrolled patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

Administration of UDCA for 12 months significantly reduced the incidence of gallstones after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. These findings suggest that UDCA administration prevents gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02490111

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in preventing gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer.

Introduction

The incidence of gallstones, which has been reported to be higher in patients who have undergone gastrectomy than in the general population, varies from 6.1% to 25.7% depending on the report.1,2,3,4 Symptomatic gallstone disease accounts for approximately 5% of gallstone cases.2,3,5 Despite the small fraction of symptomatic gallstones, cholecystectomy is more challenging after gastrectomy because of an increased risk of conversion, bile duct injuries, and longer operating times.6,7 An endoscopic approach is also more challenging owing to difficult intubation and cannulation associated with altered anatomy and a high failure rate.8 Therefore, preventing gallstone formation after gastrectomy is needed to avoid burdensome surgical procedures.

Gallstones after bariatric surgery are mainly caused by rapid weight loss,9 whereas gallstones after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer arise from various mechanisms. Vagal nerve resection during gastrectomy has a major influence on the gallbladder’s contractile ability. Previous studies have shown that gastrectomy abolishes phasic contraction of the gallbladder, increasing the propensity for bile salt precipitation and gallstone formation.10,11 Another proposed mechanism is lymph node dissection, specifically in the hepatoduodenal ligament, which results in the dissection of nerve fibers near the gallbladder.12 In addition, nonphysiological reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract13,14 and an altered response to and secretion of cholecystokinin15 are possible mechanisms of gallstone formation. Cholestasis due to decreased gallbladder contraction16 for various reasons can be summarized as the main mechanism of gallstone formation after gastrectomy.

There have been several studies of prophylactic cholecystectomy during gastrectomy owing to the high incidence of gallstone formation, especially in patients with obesity undergoing bariatric surgery. However, the benefit of concomitant prophylactic cholecystectomy remains unclear because most patients with gallstones are asymptomatic.4,17,18,19 Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that cholecystectomy has abnormal metabolic consequences, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,20 and concomitant cholecystectomy during bariatric surgery can be more difficult and may be associated with a higher incidence of complications.21 Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy for future gallstones is not justified. However, some studies have revealed that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) administration can prevent gallstone formation after bariatric surgery.22,23,24,25,26,27 Ursodeoxycholic acid can improve gallbladder contractility28 by decreasing cholesterol content in the plasma membrane of muscle cells29 and can stimulate biliary secretion, leading to relieved cholestasis.30 Moreover, other mechanisms of action, such as protection of damaged cholangiocytes and stimulation of detoxification of hydrophobic bile acids, may contribute to UDCA’s effect.31 Therefore, UDCA can be a good and safe alternative to prophylactic cholecystectomy.

Thus, it is necessary to verify the efficacy of UDCA for patients who have undergone gastrectomy owing to gastric cancer. However, to our knowledge, there have been few studies of UDCA regarding the prevention of gallstone formation after gastrectomy. This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of UDCA in preventing gallstone formation after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer.

Methods

Study Design

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted in 12 institutions in Korea. Participants were enrolled between May 26, 2015, and January 9, 2017; follow-up ended January 8, 2018. All participants, including those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at all of the participating institutions (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Asan Medical Center, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, Kyoungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, Ajou University Hospital, National Cancer Center, Boramae Medical Center, Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Catholic University Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Samsung Medical Center, and Chungnam National University Hospital; trial protocol in Supplement 1) and was conducted in accordance with provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.32 An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed the progress of the study.

Study Population

Patients 19 years of age or older, with a diagnosis of gastric cancer, who underwent total, distal, or proximal gastrectomy were eligible to participate. Before taking part in the trial, all of the surgeons had performed more than 200 gastrectomies, and their respective hospitals regularly performed at least 100 gastrectomies per year. The hepatic branch of the vagus nerve was routinely removed during full lymph node dissection. Patients with pathological stage II or higher gastric cancer received adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were thoroughly monitored for the administration of chemotherapeutic agents to assess any safety issues. Major inclusion criteria included D1+ or D2 lymph node dissection, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 or lower,33 and a patient life expectancy of at least 3 months. Major exclusion criteria were biliary infection or obstruction, a previous cholecystectomy, preexisting gallstones, pylorus-preserving gastrectomy, active gastrointestinal inflammation (ulcer, pancreatitis, colitis, or enteritis), liver dysfunction, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) greater than 37, uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, hypersensitivity to bile acid or UDCA, and cancers of another organ within 5 years prior to enrollment.

Randomization

Individuals who met all inclusion criteria and who had no exclusion criteria at screening were randomly assigned (by the investigators) to receive 300 mg of UDCA, 600 mg of UDCA, or placebo at a ratio of 1:1:1, after written informed consent (from participants) within 2 weeks after gastrectomy. An independent statistician generated a random allocation sequence based on stratification factors; thus, a stratified block randomization method was used to randomly assign participants at each study site. The proc plan procedure in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) (stratification factors were lymph node dissection range and type of gastrectomy) was used for randomization at each site, and participants were assigned by the investigators via an interactive web-response system. Neither participants nor relevant investigators were aware of these assignments.

Interventions

After randomization, 300 mg of UDCA, 600 mg of UDCA, and placebo were administered daily for 52 weeks. To maintain blindness, all capsules were made in the same shape and administered twice daily after breakfast and dinner (one 300-mg capsule once daily and 1 placebo capsule once daily for the 300-mg group, one 300-mg capsule twice daily for the 600-mg group, and 1 placebo capsule twice daily for the placebo group). Drug adherence was checked at every visit. If adherence was 85% or less, the investigator retrained the participant.

At screening, all participants underwent abdominal ultrasonography to discover preexisting gallstones, if results were not available from the previous 6 weeks. Abdominal ultrasonography was then performed every 3 months up to 12 months to confirm gallstone formation. At each visit, participants were evaluated for drug adherence. Any participant with confirmed gallstone formation during treatment was removed from the study at the time of confirmation. Safety assessments were based on adverse events, laboratory test results (hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis), physical examinations, and vital signs at each visit.

Confirmation of gallstone formation was based primarily on ultrasonography results, supplemented by abdominal computed tomography scans. Criteria for gallstone diagnosis by abdominal ultrasonography were as follows: highly reflective echo, posterior acoustic shadowing, and gravitational dependence.34 To ensure reliability of the results of abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography scans, all images obtained were reevaluated by 3 independent blinded evaluators. The presence of gallstones not visible on computed tomography scans but visible on ultrasonographic images was also determined by these evaluators. Only diagnoses agreed on by 2 or more evaluators were accepted. Biliary sludge visible on computed tomography scans or ultrasonographic images was not regarded as gallstones.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the proportion of patients developing gallstones within 12 months after gastrectomy. Adverse drug reactions during the study period were evaluated as the secondary end point.

Statistical Analysis

The study was designed to demonstrate that 300 mg or 600 mg of UDCA was superior to placebo regarding gallstone prevention. Assuming that the primary end point was 7% in the UDCA groups35 and 18% in the placebo group,3,36 the minimum sample size necessary to detect a difference with 80% statistical power (α = .05; 2-sided test) was 138 per group (not considering the multiplicity adjustment of α using a fixed-sequence method: 600 mg of UDCA vs placebo, and 300 mg of UDCA vs placebo).37

Efficacy was evaluated by both the full analysis set (FAS, based on the intention-to-treat principle) and the per-protocol set (PPS); FAS findings were interpreted as the main results. The FAS comprised participants who underwent at least 1 evaluation of gallstone formation after randomization and did not violate the inclusion or exclusion criteria. The PPS comprised participants who completed the trial without any significant protocol deviations that could affect efficacy. Observed-case analysis included those with missing data, which were not imputed for missing values. To determine the superiority of UDCA vs placebo in preventing gallstone formation, sequential multiple testing was performed for each dose group according to the fixed-sequence method: step 1, superiority testing for 600 mg of UDCA vs placebo (5% significance level); step 2, superiority testing for 300 mg of UDCA vs placebo (5% significance level). The step 2 test was performed only if results of the step 1 test were statistically significant. The test in each step used the logistic regression model with treatment group as a factor and with range of lymph node dissections and type of gastrectomy as covariates; test results were presented (by treatment group) as odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs for participants who developed gallstones within 12 months.

Data on time to gallstone formation after administration of the study product were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier plots and the Cox proportional hazards regression model, with treatment groups as the factor and with range of lymph node dissections and type of gastrectomy as covariates. Clinical data were collected and validated using the Rave Electronic Data Capture system (Medidata Institute). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4.

Results

Study Participants

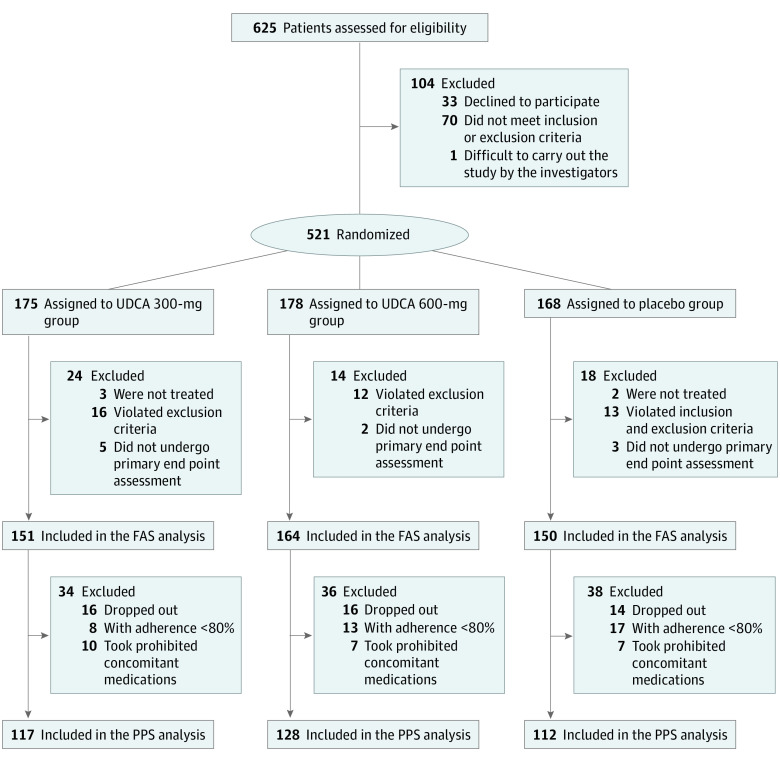

A total of 625 patients were identified as eligible for the study from 12 institutions in the Republic of Korea between May 4, 2015, and January 9, 2017; follow-up ended January 8, 2018. After exclusion of 104 patients, including 33 who declined to participate, 521 were randomized (175 received 300 mg of UDCA, 178 received 600 mg of UDCA, and 168 received placebo) (Figure 1). After follow-up, the FAS comprised 151 patients in the 300-mg group, 164 patients in the 600-mg group, and 150 patients in the placebo group. The baseline characteristics for the 3 groups are shown in Table 1 (the results of PPS analysis are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The 3 groups were equally randomized and did not show any significant differences regarding age, sex, body mass index, smoking, drinking, stage of gastric cancer, and surgical factors.

Figure 1. Flow of Patient Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

FAS indicates full analysis set; PPS, per-protocol set, and UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patientsa.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| UDCA, 300 mg (n = 151) | UDCA, 600 mg (n = 164) | Placebo (n = 150) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 56.0 (47.0-64.0) | 57.0 (50.0-64.0) | 56.0 (48.0-65.0) |

| Male sex | 99 (65.6) | 110 (67.1) | 102 (68.0) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 23.4 (21.3-25.3) | 23.2 (21.4-25.1) | 23.6 (21.9-25.7) |

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 30 (19.9) | 38 (23.2) | 34 (22.7) |

| No | 76 (50.3) | 74 (45.1) | 67 (44.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 45 (29.8) | 52 (31.7) | 49 (32.7) |

| Alcohol drinker | |||

| Yes | 47 (31.1) | 64 (39.0) | 48 (32.0) |

| No | 70 (46.4) | 68 (41.5) | 67 (44.7) |

| Former drinker | 34 (22.5) | 32 (19.5) | 35 (23.3) |

| T stage | |||

| 1 | 112 (74.2) | 125 (76.2) | 113 (75.3) |

| 2 | 20 (13.2) | 17 (10.4) | 16 (10.7) |

| 3 | 10 (6.6) | 11 (6.7) | 8 (5.3) |

| 4 | 8 (5.3) | 11 (6.7) | 12 (8.0) |

| N stage | |||

| 0 | 131 (86.8) | 133 (81.1) | 120 (80.0) |

| 1 | 2 (1.3) | 14 (8.5) | 14 (9.3) |

| 2 | 8 (5.3) | 11 (6.7) | 8 (5.3) |

| 3 | 10 (6.6) | 6 (3.7) | 8 (5.3) |

| M stage | |||

| 0 | 149 (98.7) | 162 (98.8) | 149 (99.3) |

| 1 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Stage | |||

| IA | 109 (72.2) | 117 (71.3) | 102 (68.0) |

| IB | 16 (10.6) | 16 (9.8) | 21 (14.0) |

| IIA | 8 (5.3) | 5 (3.1) | 7 (4.7) |

| IIB | 6 (4.0) | 14 (8.5) | 7 (4.7) |

| IIIA | 3 (2.0) | 3 (1.8) | 4 (2.7) |

| IIIB | 4 (2.7) | 6 (3.7) | 4 (2.7) |

| IIIC | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.7) |

| IV | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Gastrectomy type | |||

| Total | 16 (10.6) | 18 (11.0) | 13 (8.7) |

| Distal | 127 (84.1) | 138 (84.2) | 127 (84.7) |

| Proximal | 8 (5.3) | 8 (4.9) | 10 (6.7) |

| Gastrectomy method | |||

| Open | 22 (14.6) | 19 (11.6) | 13 (8.7) |

| Laparoscopy | 129 (85.4) | 145 (88.4) | 137 (91.3) |

| Lymph node resection range | |||

| D1+ | 66 (43.7) | 67 (40.9) | 64 (42.7) |

| D2 | 85 (56.3) | 97 (59.1) | 86 (57.3) |

| Stomach reconstruction type | |||

| Billroth | |||

| I | 30 (19.9) | 34 (20.7) | 26 (17.3) |

| II | 32 (21.2) | 47 (28.7) | 43 (28.7) |

| Roux-en-Y | 58 (38.4) | 52 (31.7) | 53 (35.3) |

| Other | 31 (20.5) | 31 (18.9) | 28 (18.7) |

| ECOG performance status, No. | |||

| 0 | 77 (51.0) | 82 (50.0) | 71 (47.3) |

| 1 | 74 (49.0) | 82 (50.0) | 79 (52.7) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy after gastrectomy | 24 (15.9) | 30 (18.3) | 24 (16.0) |

| 95% CI for differenceb | –0.11 (–8.38 to 8.17) | 2.29 (–6.04 to 10.63) | [Reference] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IQR, interquartile range; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

No significant differences were identified between the treatment groups in any baseline variables.

Calculated with the χ2 test.

Outcomes

In the FAS (311 men; median age, 56.0 years [interquartile range, 48.0-64.0 years]), the proportions of patients developing gallstones within 12 months after gastrectomy were 8 of 151 (5.3%) in the 300-mg group, 7 of 164 (4.3%) in the 600-mg group, and 25 of 150 (16.7%) in the placebo group. The odds ratios (vs placebo) for gallstone formation were 0.27 (95% CI, 0.12-0.62; P = .002) in the 300-mg group and 0.20 (95% CI, 0.08-0.50; P < .001) in the 600-mg group (Table 2). The differences in proportions between the 2 UDCA groups compared with the placebo group were significant at −11.4% (95% CI, −18.3% to −4.4%) for the 300-mg group and −12.4% (95% CI, −19.1% to −5.7%) for the 600-mg group (results for the PPS are shown in eTable 2 in Supplement 2). All of the gallstones detected were gallbladder stones. No bile duct or intrahepatic duct stones were detected during the study period.

Table 2. Primary Outcome: Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 12 Months After Gastrectomy.

| Outcome | UDCA, 300 mg (n = 151) | UDCA, 600 mg (n = 164) | Placebo (n = 150), No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), % | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), % | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | ||

| Incidence of gallstones | 8 (5.3) | –11.4 (–18.3 to –4.4) | 0.27 (0.12 to 0.62) | .002 | 7 (4.3) | –12.4 (–19.1 to –5.7) | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.50) | <.001 | 25 (16.7) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

For superiority compared with the placebo group (reference).

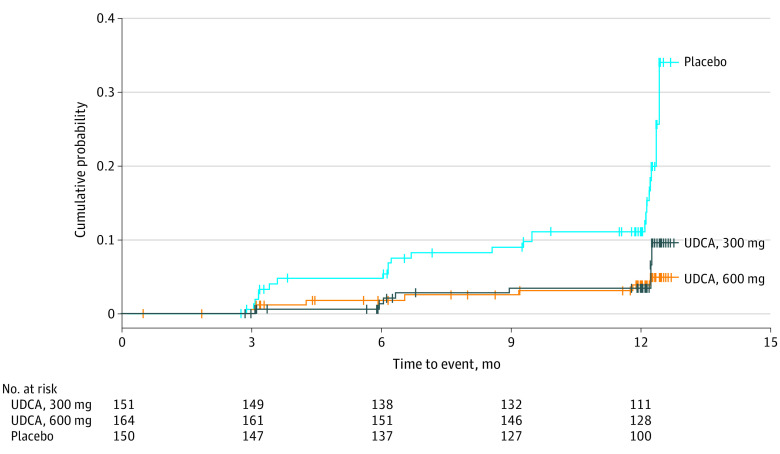

The proportions of patients developing gallstones at each time point (3, 6, and 9 months after gastrectomy) are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 2 (results for the PPS are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 2). The preventive effects of UDCA on gallstone formation were observed 3 months after administration. Figure 2 indicates the time to gallstone formation after administration of the investigational product and the cumulative probability of gallstone formation with a Kaplan-Meier plot. A Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed hazard ratios (vs placebo) of 0.3 (95% CI, 0.1-0.7) in the 300-mg group and 0.2 (95% CI, 0.1-0.5) in the 600-mg group. In subgroup analysis of patients with a D2 lymph node dissection, the proportions of patients developing gallstones within 12 months were significantly lower in the treatment groups vs placebo group (6 of 85 [7.1%] in the 300-mg group, 4 of 97 [4.1%] in the 600-mg group, and 13 of 86 [15.1%] in the placebo group). Compared with the placebo group, odds ratios for gallstone formation were 0.39 (95% CI, 0.14-1.10; P = .07) in the 300-mg group and 0.23 (95% CI, 0.07-0.74; P = .01) in the 600-mg group. Gallstone complications occurred in 4 patients (1 case of acute cholangitis and 3 of cholecystitis) during the study period, all of whom were in the placebo group.

Figure 2. Cumulative Probability of Gallstone Formation According to Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA) Dosage (Full Analysis Set).

Tic marks indicate censored data.

Adverse Drug Reactions

The safety set included 516 patients who received at least 1 dose of investigational product after randomization. No statistically significant differences in the incidence of adverse drug reactions were noted among the 3 groups (Table 3). The most common symptom was nausea (4 of 516 [0.8%]), followed by skin rash (3 of 516 [0.6%]). No serious adverse drug reactions were reported during the study period. Two patients died during the study period: one in the 600-mg group and the other in the placebo group. Both deaths were associated with cancer recurrence, regardless of adverse drug reactions.

Table 3. Adverse Drug Reactionsa.

| Adverse drug reactions | UDCA, 300 mg (n = 172) | UDCA, 600 mg (n = 178) | Placebo (n = 166) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Exact 95% CI | No. (%) | Exact 95% CI | No. (%) | Exact 95% CI | ||

| Participants with ADRs | 8 (4.7) | 2.03-8.96 | 3 (1.7) | 0.35-4.85 | 3 (1.8) | 0.37-5.19 | .18 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 3 (1.7) | NA | 2 (1.1) | NA | 2 (1.2) | NA | NA |

| Nausea | 2 (1.2) | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | NA |

| Diarrhea | 0 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | NA |

| Vomiting | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Skin or subcutaneous symptoms | 4 (2.3) | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | NA |

| Rash | 2 (1.2) | NA | 0 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | NA |

| Alopecia | 2 (1.2) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Pruritus | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Urticaria | 0 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Others | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Chest discomfort | 1 (0.6) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| Participants with serious ADRs | 0 | 0.00-2.12 | 0 | 0.00-2.05 | 0 | 0.00-2.20 | NA |

| Participants with ADRs leading to death | 0 | 0.00-2.12 | 0 | 0.00-2.05 | 0 | 0.00-2.20 | NA |

Abbreviations: ADR, adverse drug reaction; NA, not applicable; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Patients analyzed who had received at least 1 dose of trial medication after randomization.

Discussion

Previous research on UDCA for the prevention of gallstone formation after gastric surgery was performed mostly for patients with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery. There were several randomized clinical trials from the 1990s to 2000s, and results showed that gallstone formation was significantly reduced in the UDCA vs placebo groups.24,25,26,35 Taken together, these studies indicate that UDCA administration after bariatric surgery can significantly reduce the risk of gallstone formation by approximately 57%.23 However, these studies were limited by small sample sizes and short durations of UDCA administration (mostly 6 months). Two recent studies also revealed the protective effect of UDCA, but both studies had the disadvantage of being retrospective.22,27 To demonstrate the effectiveness of UDCA more clearly, a large-scale randomized clinical trial on the use of UDCA for preventing symptomatic gallstone disease after bariatric surgery has been under way in recent years.38 To our knowledge, our study is the first large-scale randomized clinical study for patients with gastric cancer, and it differs from previous studies in that rapid weight loss is not the main mechanism of gallstone formation. Cholestasis due to decreased gallbladder contraction is considered to be the major mechanism of gallstone formation after gastric cancer surgery.10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Therefore, we excluded patients with a body mass index greater than 37 because of the rapid weight loss expected after surgery. Although bariatric surgical procedures include several other types of surgery (ie, vertical banded gastroplasty and gastric bypass surgery) besides gastrectomy, all surgical procedures for patients with gastric cancer are gastrectomies. Therefore, the patients in our study were more uniform. In addition, our study revealed the effectiveness of UDCA by introducing 2 different UDCA dose groups and a longer duration of administration (12 months).

In our study, gallstone formation was observed in 40 (8.6%) of the 465 patients in the FAS. The age of these patients was similar to that of a previous Korean study,39 but the proportion of male participants in our study was higher (28 of 40 [70.0%]), which is owing to a greater participation by men in our study. Fukagawa et al3 reported that formation of gallstones was observed in 25.7% (173 of 672) of patients who underwent gastrectomy, and 64.7% (112 of 173) developed gallstones within 1 year after gastrectomy. Thus, we planned to administer the trial drug for 1 year, while assuming that most gallstones occur during the early postoperative period. In our study, the incidence of gallstones within 1 year after gastrectomy in the placebo group was 16.7% (25 of 150), which was relatively higher than in previous studies. This result indicates that most gallstones are likely to develop at an early stage after gastrectomy, considering the high incidence in 1 year. Therefore, the planned UDCA treatment duration of 1 year in this study is considered an appropriate design. In addition, we administered UDCA for a longer period than in previous studies,22,23,24,25,26,27 which typically administered the drug for only 6 months. After gastrectomy, anemia, weight loss, and malnutrition occur most frequently within 1 year after surgery.40 In advanced gastric cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy is performed within 1 year after surgery. Therefore, it is important to prevent gallstones and associated complications for 1 year after surgery.

Not all gallstones need to be surgically treated. Gallstones requiring surgical treatment are those in patients with symptoms or complications (ie, acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, or gallstone pancreatitis).41 Previous studies have reported that only 4% to 7% of patients with gallstones require treatment.2,3,5 Therefore, it has been suggested that prophylactic cholecystectomy is unnecessary because of the low incidence of complications.4,17 However, despite this low incidence, once gallstone complications occur, there are difficulties with subsequent treatments, such as cholecystectomy6 and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.8 Thus, it is necessary to actively consider simple preventive measures, such as UDCA administration, especially for patients with early gastric cancer who are expected to be long-term survivors. In our study, gallstone complications occurred in only 4 patients in the placebo group. Ursodeoxycholic acid may reduce not only the incidence of gallstones but also the number of gallstone complications.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, because of the short study period, we could not confirm how many cholecystectomies were prevented by UDCA therapy; for such confirmation, larger sample sizes and longer observation periods are needed. In addition, it has not been evaluated whether taking UDCA for 1 year affects gallstone formation after 1 year. Our primary end point was the incidence of gallstones within 1 year, but some complications were reported during the short study period. Therefore, further analysis of long-term follow-up data, including the occurrence of gallstones or acute cholecystitis after stopping UDCA treatment, as well as the cost-effectiveness of treatment, may be meaningful. The administration of UDCA may actually reduce the number gallstone complications, such as biliary pain and acute cholecystitis,42 although an investigation of this possibility was not a principal feature of our study design. As a second limitation, this study was conducted in the Republic of Korea, where the incidence of gastric cancer is relatively high, so it may be difficult to generalize the study findings to other regions of the world. However, the mechanism involved in gallstone development after gastrectomy is no different for other racial/ethnic groups, and the efficacy of UDCA in preventing gallstones had already been proven, regardless of race/ethnicity.23 Despite these limitations, our study showed statistically significant efficacy for UDCA against the primary end point in an adequate number of patients.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial showed that 12 months of UDCA administration significantly reduced the incidence of gallstones after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. All reported adverse reactions were mild and tolerable, as reported in the previous literature.43 Although it is difficult to make any definitive conclusions, we suggest that gallstone formation and its complications may be prevented by the use of UDCA rather than prophylactic cholecystectomy. In the future, studies comprising a larger number of patients with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm whether the use of UDCA can reduce the number of patients undergoing subsequent cholecystectomy.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics (Per-Protocol Set)

eTable 2. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 12 Months After Gastrectomy (Per-Protocol Set)

eTable 3. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 3, 6, 9 Months After Gastrectomy (Full-Analysis Set)

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 3, 6, 9 Months After Gastrectomy (Per-Protocol Set)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Park DJ, Kim KH, Park YS, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Risk factors for gallstone formation after surgery for gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16(2):98-104. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2016.16.2.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi T, Hisanaga M, Kanehiro H, Yamada Y, Ko S, Nakajima Y. Analysis of risk factors for the development of gallstones after gastrectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92(11):1399-1403. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukagawa T, Katai H, Saka M, Morita S, Sano T, Sasako M. Gallstone formation after gastric cancer surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(5):886-889. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0832-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura J, Kunisaki C, Takagawa R, et al. Is routine prophylactic cholecystectomy necessary during gastrectomy for gastric cancer? World J Surg. 2017;41(4):1047-1053. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3831-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li VK, Pulido N, Martinez-Suartez P, et al. Symptomatic gallstones after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(11):2488-2492. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0422-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser SA, Sigman H. Conversion in laparoscopic cholecystectomy after gastric resection: a 15-year review. Can J Surg. 2009;52(6):463-466. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki A, Nakajima J, Nitta H, Obuchi T, Baba S, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with a history of gastrectomy. Surg Today. 2008;38(9):790-794. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3726-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreels TG. ERCP in the patient with surgically altered anatomy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(9):343. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0343-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iglézias Brandão de Oliveira C, Adami Chaim E, da Silva BB. Impact of rapid weight reduction on risk of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2003;13(4):625-628. doi: 10.1381/096089203322190862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ura K, Sarna SK, Condon RE. Antral control of gallbladder cyclic motor activity in the fasting state. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):295-302. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91813-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehnberg O, Haglund U. Gallstone disease following antrectomy and gastroduodenostomy with or without vagotomy. Ann Surg. 1985;201(3):315-318. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198503000-00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi SQ, Ohta T, Tsuchida A, et al. Surgical anatomy of innervation of the gallbladder in humans and Suncus murinus with special reference to morphological understanding of gallstone formation after gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(14):2066-2071. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pezzolla F, Lantone G, Guerra V, et al. Influence of the method of digestive tract reconstruction on gallstone development after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 1993;166(1):6-10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80573-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi T, Yamamura T, Yokoyama E, et al. Impaired contractile motility of the gallbladder after gastrectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81(8):672-677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue K, Fuchigami A, Hosotani R, et al. Release of cholecystokinin and gallbladder contraction before and after gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1987;205(1):27-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portincasa P, Altomare DF, Moschetta A, et al. The effect of acute oral erythromycin on gallbladder motility and on upper gastrointestinal symptoms in gastrectomized patients with and without gallstones: a randomized, placebo-controlled ultrasonographic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3444-3451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bencini L, Marchet A, Alfieri S, et al. ; Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) . The Cholegas trial: long-term results of prophylactic cholecystectomy during gastrectomy for cancer—a randomized-controlled trial. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22(3):632-639. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0879-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dakour-Aridi HN, El-Rayess HM, Abou-Abbass H, Abu-Gheida I, Habib RH, Safadi BY. Safety of concomitant cholecystectomy at the time of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(6):934-941. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yardimci S, Coskun M, Demircioglu S, Erdim A, Cingi A. Is concomitant cholecystectomy necessary for asymptomatic cholelithiasis during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? Obes Surg. 2018;28(2):469-473. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2867-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Relationship of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with cholecystectomy in the US population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):952-958. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ammori BJ, Vezakis A, Davides D, Martin IG, Larvin M, McMahon MJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in morbidly obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(11):1336-1339. doi: 10.1007/s004640000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coupaye M, Calabrese D, Sami O, Msika S, Ledoux S. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-685. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uy MC, Talingdan-Te MC, Espinosa WZ, Daez ML, Ong JP. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the prevention of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2008;18(12):1532-1538. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9587-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller K, Hell E, Lang B, Lengauer E. Gallstone formation prophylaxis after gastric restrictive procedures for weight loss: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238(5):697-702. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094305.77843.cf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wudel LJ Jr, Wright JK, Debelak JP, Allos TM, Shyr Y, Chapman WC. Prevention of gallstone formation in morbidly obese patients undergoing rapid weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. J Surg Res. 2002;102(1):50-56. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams C, Gowan R, Perey BJ. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid in the prevention of gallstones during weight loss after vertical banded gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 1993;3(3):257-259. doi: 10.1381/096089293765559278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdallah E, Emile SH, Elfeki H, et al. Role of ursodeoxycholic acid in the prevention of gallstone formation after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Today. 2017;47(7):844-850. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1446-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Heijning BJ, van de Meeberg PC, Portincasa P, et al. Effects of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on in vitro gallbladder contractility in patients with cholesterol gallstones. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(1):190-196. doi: 10.1023/A:1026635124115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guarino MP, Cong P, Cicala M, Alloni R, Carotti S, Behar J. Ursodeoxycholic acid improves muscle contractility and inflammation in symptomatic gallbladders with cholesterol gallstones. Gut. 2007;56(6):815-820. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.109934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jazrawi RP, de Caestecker JS, Goggin PM, et al. Kinetics of hepatic bile acid handling in cholestatic liver disease: effect of ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(1):134-142. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(94)94899-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paumgartner G, Beuers U. Ursodeoxycholic acid in cholestatic liver disease: mechanisms of action and therapeutic use revisited. Hepatology. 2002;36(3):525-531. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bortoff GA, Chen MY, Ott DJ, Wolfman NT, Routh WD. Gallbladder stones: imaging and intervention. Radiographics. 2000;20(3):751-766. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma16751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugerman HJ, Brewer WH, Shiffman ML, et al. A multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, prospective trial of prophylactic ursodiol for the prevention of gallstone formation following gastric-bypass–induced rapid weight loss. Am J Surg. 1995;169(1):91-96. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80115-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue K, Fuchigami A, Higashide S, et al. Gallbladder sludge and stone formation in relation to contractile function after gastrectomy: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 1992;215(1):19-26. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakamaki K, Kamiura T, Morita Y, et al. Current practice on multiplicity adjustment and sample size calculation in multi-arm clinical trials: an industry survey in Japan. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50(6):846-852. doi: 10.1177/2168479016651660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boerlage TCC, Haal S, Maurits de Brauw L, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid for the prevention of symptomatic gallstone disease after bariatric surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (UPGRADE trial). BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0674-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park YH, Park SJ, Jang JY, et al. Changing patterns of gallstone disease in Korea. World J Surg. 2004;28(2):206-210. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6879-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim KH, Park DJ, Park YS, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Actual 5-year nutritional outcomes of patients with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2017;17(2):99-109. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2017.17.e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warttig S, Ward S, Rogers G; Guideline Development Group . Diagnosis and management of gallstone disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g6241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomida S, Abei M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Long-term ursodeoxycholic acid therapy is associated with reduced risk of biliary pain and acute cholecystitis in patients with gallbladder stones: a cohort analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30(1):6-13. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hempfling W, Dilger K, Beuers U. Systematic review: ursodeoxycholic acid—adverse effects and drug interactions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(10):963-972. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics (Per-Protocol Set)

eTable 2. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 12 Months After Gastrectomy (Per-Protocol Set)

eTable 3. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 3, 6, 9 Months After Gastrectomy (Full-Analysis Set)

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients Developing Gallstones Within 3, 6, 9 Months After Gastrectomy (Per-Protocol Set)

Data Sharing Statement