Key Points

Question

What proportion of opioid-naive patients who undergo cardiac surgery have new persistent opioid use 90 days after surgery and is there an association with the amount of opioids prescribed at discharge?

Findings

In this cohort study that used data from a large, national administrative database for patients with privately managed health insurance, 9.8% of patients developed new persistent opioid use after cardiac surgery. Patients were at increased risk when prescribed greater than the 300 oral morphine equivalents (mg) or approximately 40 tablets of oxycodone, 5 mg.

Meaning

Decreasing the amount of opioids prescribed at discharge may lower the likelihood for persistent use.

Abstract

Importance

The overuse of opioids for acute pain management has led to an epidemic of persistent opioid use.

Objective

To determine the proportion of opioid-naive patients who develop persistent opioid use after cardiac surgery and investigate the association between the initial amount of opioids prescribed at discharge and the likelihood of developing new persistent opioid use.

Design, Setting, and Participants

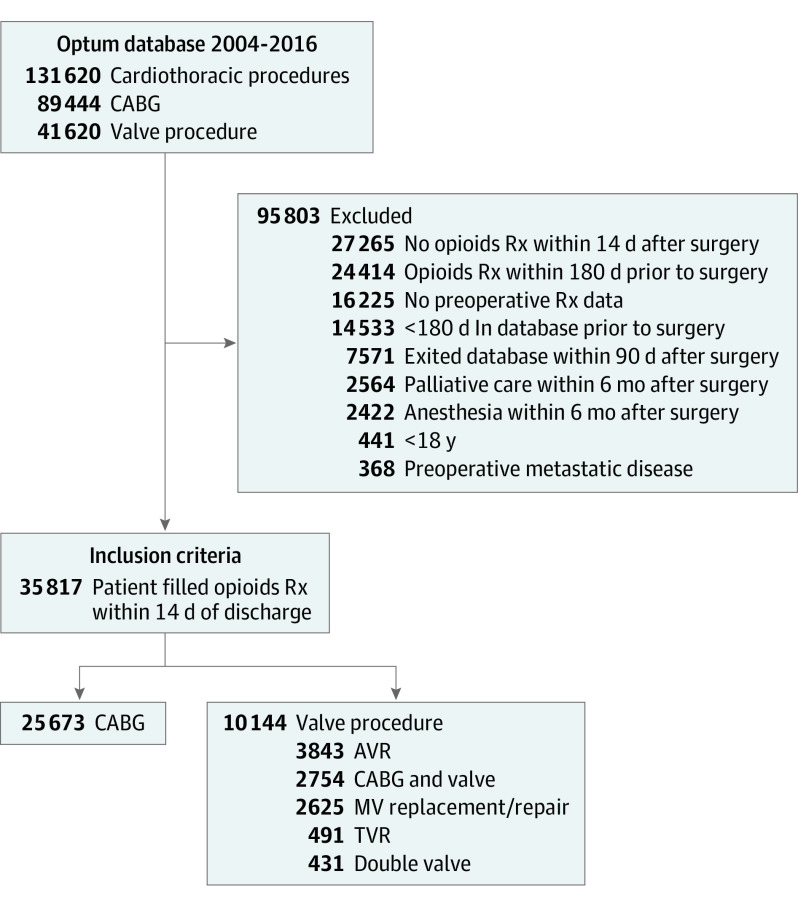

This retrospective cohort study used data from a national administrative claims database from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2016 and included 35 817 patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (25 673 [71.7%]) and heart valve (10 144 [28.3%]) procedures. All patients were opioid-naive within 180 days before the index procedure and filled an opioid prescription within 14 days after surgery.

Exposures

Opioid medications after cardiac surgery.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of opioid-naive patients who developed new persistent opioid use within 90 to 180 days after surgery was determined. Oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) were calculated for the first opioid prescription filled after discharge. A multivariable logistic regression with cubic splines was used to analyze the association among the OMEs at discharge and likelihood of developing persistent opioid use.

Results

Of the 25 673 patients who underwent CABG, the mean (SD) age for those without (n = 23 064) vs with (n = 2609) persistent opioid use was 62.9 (9.8) years vs 61.6 (9.7) years, respectively, and the number who were men were 18 758 (81.3%) vs 1998 (76.6%). Of the 10 144 patients who underwent heart valve surgery, the mean (SD) age for those without (n = 9343) vs with (n = 821) persistent opioid use was 63.2 (12.4) years vs 61.2 (12.5) years, respectively, and the number who were men were 6378 (68.3%) vs 511 (62.2%). Persistent opioid use is a substantial concern after cardiac surgery and occurred in 2609 patients undergoing CABG (10.2%) and 821 valve surgery patients (8.1%; P = .001). The likelihood for developing persistent opioid use was decreased among heart valve surgery recipients (odds ratio [OR], 0.78; P < .001) and increased for patients who were women; younger; with preoperative congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes, kidney failure, chronic pain, and alcoholism; and those taking preoperative benzodiazepines and muscle relaxants (women: OR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.03-1.26]; younger age: OR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.01-1.02]; congestive heart failure: OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.06-1.30]; chronic lung disease: OR, 1.32 [95% CI, 1.19-1.45]; diabetes: OR, 1.27 [95% CI, 1.15-1.40]; kidney failure: OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.00-1.37]; chronic pain: OR, 2.71 [95% CI, 2.10-3.56]; alcoholism: OR, 1.56 [95% CI, 1.23-2.00]; benzodiazepines: OR, 1.71 [95% CI, 1.52-1.91]; muscle relaxants: OR, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.51-2.02]; all P < .001). Furthermore, we found that when patients were prescribed more than approximately 300 mg of OMEs at discharge, they had a significantly increased risk of new persistent opioid use than with lower opioid prescriptions.

Conclusions and Relevance

Opioids are used extensively after cardiothoracic surgery and nearly 1 of 10 patients will continue to use opioids over 90 days after surgery. Furthermore, higher OMEs prescribed at discharge were significantly associated with developing persistent use. Centers must adopt protocols to increase patient education and limit opioid prescriptions after discharge.

This cohort study examines the proportion of opioid-naive patients who develop persistent opioid use after cardiac surgery.

Introduction

Opioid use in the US has been declared a public health emergency, with opioid-related deaths increasing to 47 600 in 2017 and accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdoses.1 This accounts for more deaths each year than motor vehicle collisions or breast cancer, respectively. In addition to overdose and death, opioid use and dependence produces a substantial economic burden to the health care system and increased morbidity among those affected.2,3,4

The causes for the opioid crisis are complex and multifactorial, but it is known that surgery is a risk factor for new persistent opioid use.5,6,7,8,9 Additionally, opioids are frequently overprescribed during the postoperative period, which leads to increased consumption regardless of postoperative pain.10,11,12,13 Recent studies have demonstrated that new persistent opioid use occurs in 3% to 10% of patients after minor and major general surgery procedures5,7,9 and, in smaller series, occurs in similar rates among patients undergoing cardiac surgery.6,9 However, large population studies that examine this risk after cardiac surgery in the US are lacking. These data are crucial as opioids are used extensively after cardiac surgery for postoperative pain control.

The objective of this study was to evaluate patients who underwent cardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass and heart valve surgery) surgery using a large, national administrative database to evaluate the following: (1) percentage of opioid-naive patients who fill an opioid prescription postoperatively, (2) the proportion of patients who have opioid dependence 90 to 180 days after surgery, and (3) the association between the amount of initial opioids prescribed at discharge (oral morphine equivalents [OMEs]) and the risk for persistent opioid use.

Methods

Study Design

We examined data from patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or heart valve repair or replacement from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2016, using the OptumInsights Informatics Data Mart (Optum), a large, private-payer administrative claims database. We had 3 main objectives: (1) determine the number of opioid-naive patients who fill opioid prescriptions after cardiothoracic surgery (CABG, valve surgery), (2) determine the proportion of opioid-naive patients who undergo cardiothoracic surgery and are new persistent opioid users within 90 to 180 days after surgery, and (3) evaluate the association between total OMEs from the first opioid prescription that is filled after surgery and the risk for persistent opioid use 90 to 180 days after surgery. The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania approved this research and no informed consent was required because the patient data were deidentified.

Study Population

Patients who underwent cardiac surgery were included in the study if they underwent CABG, aortic valve replacement, mitral valve repair, mitral valve replacement, tricuspid valve repair, or tricuspid valve replacement and were identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for the respective operations. All patients were identified from the Optum database, which contains deidentified claims and prescription data for commercially insured and Medicare-managed care enrollees. If patients had multiple cardiac operations while in the Optum database, only the first procedure was analyzed. The Optum database comprises a geographically diverse population (24% West, 24% Midwest, 42% South, and 10% Northeast) and contains approximately 12 to 15 million covered patients per year.

Patients were then stratified as undergoing CABG or heart valve surgery. The goal of the inclusion and exclusion criteria was to create a patient cohort that was opioid naive (no opioids within 180 days before the index operation) and was prescribed opioids within the first 14 days after the index operation (Figure 1). Patients were excluded if they were not present in the Optum database for at least 180 days preoperatively or lacked prescription data from the Optum database. We required all patients to have a minimum of 90 days of postoperative enrollment in the database. Patients were excluded if they did not fill an opioid prescription within 14 days after surgery, entered palliative care within 1 year after surgery, or had a preoperative diagnosis of metastatic disease. Furthermore, we excluded patients who underwent any anesthesia procedure during the first 180 days postoperatively, as these procedures could be causes for new opioid prescriptions rather than persistent use after the initial index operation. Anesthesia procedures were identified during inpatient or outpatient visits based on all available anesthesia CPT codes.

Figure 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MV, mitral valve; Rx, prescription; TVR, tricuspid valve replacement.

Types of Opioids

Prescription data in Optum are based on prescriptions filled at a pharmacy. A patient was classified as taking an opioid if they were prescribed drugs containing hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, hydromorphone, morphine, transdermal fentanyl, tapentadol, or oxymorphone. Only tablet medications were studied, with the exception for transdermal fentanyl.

Definitions

An opioid-naive patient was defined as never filling an opioid prescription within 180 days of the index surgery. Opioid dependence was defined as a patient who filled an opioid prescription within the first 14 days after surgery and refilled an opioid prescription again after 90 to 180 days from the index procedure. The first opioid prescription prescribed for each patient was converted to an OME, which standardizes each opioid drug to an equianalgesic dosage. This allows for the comparison of different opioid medications using morphine as a reference. The initial OMEs at discharge were calculated by multiplying the number of tablets prescribed by the tablet dosage and then multiplying by a morphine equivalent conversion factor. Patient race was identified as white and nonwhite and categorized by the medical coders.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in this study was the percentage of patients who had opioid dependence at 90 to 180 days after the index cardiac (CABG or valve surgery) procedure. The secondary outcomes were the percentage of patients who had opioid dependence at 180 to 270 days after the index cardiac (CABG or valve surgery) procedure and the association of the initial opioid amount (total OME) prescribed at discharge with the likelihood for persistent opioid use within 90 to 180 days after surgery.

Patient Variables

Preoperative comorbidities were acquired from inpatient and outpatient records using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes and categorized based on the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.14,15 Patient education and income levels were extracted for each patient from the patient demographic files from the Optum database. We also determined the use of preoperative benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and antipsychotic medications for patients within 180 days before surgery.

Statistical Analysis

We determined the percentage of patients who filled opioid prescriptions for each surgery type within the first 14 days after surgery (numerator) and included all patients who underwent the respective surgery and had at least 30 days of follow-up after discharge (denominator). We determined the percentage of patients who had opioid dependence at 90 to 180 days and 180 to 270 days after each surgery type by dividing the number of patients who filled an opioid prescription during that time by the total number of patients available in each respective surgery category after meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patient demographic characteristics were stratified based on having opioid dependence at 90 to 180 days after surgery for CABG and heart valve surgery separately. Continuous variables are presented as means (SDs) and categorical variables are presented as the number of patients and the percentage. The t test was used to determine statistical significance between continuous variables and the χ2 test was used for categorical variables.

We performed an adjusted logistic regression to determine patient factors that were associated with persistent opioid use within 90 to 180 days after discharge. Patient characteristics from Table 1 were used in the adjusted logistic regression model and are presented in Table 2. Using this adjusted logistic model, we used cubic splines to determine the nonlinear association of OMEs prescribed at discharge with the odds of persistent opioid use at 90 to 180 days after surgery. For the cubic splines, the knots were determined using the quartiles of the OMEs prescribed at discharge. All tests were 2-tailed with an α set at .05. Statistical analyses were completed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and Stata, version 15 (StataCorp).

Table 1. Patient Demographic Data and Characteristics of Cardiac Surgery Patients Stratified by Persistent Opioid Use.

| Characteristics | Persistent opioid usea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG (N = 25 673) | Heart valve surgery (N = 10 144) | |||||

| No (n = 23 064) | Yes (n = 2609) | P value | No (n = 9343) | Yes (n = 821) | P value | |

| Demographics, No. (%) | ||||||

| Age | 62.9 (9.8) | 61.6 (9.7) | .02 | 63.2 (12.4) | 61.2 (12.5) | .01 |

| Men | 18 758 (81.3) | 1998 (76.6) | .02 | 6378 (68.3) | 511 (62.2) | .02 |

| White | 1 8199 (78.9) | 2012 (77.1) | .06 | 7554 (80.9) | 650 (79.2) | .26 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||||

| <12th Grade | 115 (0.5) | 15 (.6) | .01 | 30 (0.3) | 5 (0.6) | .01 |

| High school diploma | 7899 (34.2) | 1001 (38.4) | .01 | 2564 (27.4) | 276 (33.6) | .01 |

| <Bachelor’s degree | 11 514 (49.9) | 1282 (49.1) | 4933 (52.8) | 420 (51.2) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree plus | 2668 (11.6) | 228 (8.7) | 1476 (15.8) | 96 (11.7) | ||

| Income, No. (%), $ | ||||||

| <40 000 | 4632 (20.1) | 598 (22.9) | .02 | 1563 (16.7) | 139 (16.9) | .18 |

| 40 000-49 000 | 1654 (7.2) | 182 (7.0) | 691 (7.4) | 73 (8.9) | ||

| 50 000-59 000 | 1743 (7.6) | 198 (7.6) | 661 (7.1) | 66 (8.0) | ||

| 60 000-74 000 | 2323 (10.1) | 256 (9.8) | 917 (9.8) | 77 (9.4) | ||

| 75 000-99 000 | 3081 (13.4) | 332 (12.7) | 1186 (12.7) | 88 (10.7) | ||

| >100 000 | 5610 (24.3) | 517 (19.8) | 2652 (28.4) | 209 (25.5) | ||

| Year, No. (%) | ||||||

| 2004-2008 | 8156 (35.4) | 1005 (38.5) | .01 | 2414 (25.8) | 236 (28.7) | .02 |

| 2009-2012 | 7853 (34.0) | 1016 (38.9) | .02 | 3385 (36.2) | 327 (39.8) | .02 |

| 2013-2016 | 7055 (30.6) | 588 (22.5) | .01 | 3544 (37.9) | 258 (31.4) | .03 |

| Preoperative comorbidities, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 18 804 (81.5) | 2194 (84.1) | .01 | 6484 (69.4) | 599 (73.0) | .03 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4037 (17.5) | 533 (2.4) | .02 | 3086 (33.0) | 352 (42.9) | .01 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 803 (3.5) | 92 (3.5) | .91 | 1885 (20.2) | 170 (20.7) | .72 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4455 (19.3) | 676 (25.9) | .01 | 1973 (21.1) | 240 (29.2) | .01 |

| Diabetes | 6527 (28.3) | 898 (34.4) | .01 | 1551 (16.6) | 184 (22.4) | .02 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4972 (21.6) | 651 (25.0) | .01 | 2571 (27.5) | 237 (28.9) | .41 |

| Kidney failure | 1781 (7.7) | 248 (9.5) | .02 | 709 (7.6) | 83 (10.1) | .02 |

| Liver disease | 491 (2.1) | 75 (2.9) | .01 | 235 (2.5) | 34 (4.1) | .01 |

| Obesity | 3767 (16.3) | 477 (18.3) | .01 | 1001 (10.7) | 122 (14.9) | .01 |

| Weight loss | 378 (1.6) | 53 (2.0) | .14 | 226 (2.4) | 30 (3.7) | .03 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 304 (1.3) | 37 (1.4) | .67 | 141 (1.5) | 15 (1.8) | .48 |

| Paralysis | 157 (0.7) | 21 (.8) | .47 | 60 (0.6) | 8 (1.0) | .26 |

| Neurological disorders | 832 (3.6) | 128 (4.9) | .01 | 444 (4.8) | 47 (5.7) | .21 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 496 (2.2) | 90 (3.4) | .02 | 294 (3.1) | 49 (6.0) | .01 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 3444 (14.9) | 426 (16.3) | .06 | 1171 (12.5) | 133 (16.2) | .02 |

| Deficiency anemias | 3172 (13.8) | 414 (15.9) | .02 | 1419 (15.2) | 160 (19.5) | .02 |

| Depression | 1360 (5.9) | 228 (8.7) | .02 | 580 (6.2) | 76 (9.3) | .01 |

| Alcoholism | 459 (2.0) | 83 (3.2) | .02 | 135 (1.4) | 23 (2.8) | .01 |

| Chronic pain | 267 (1.2) | 89 (3.4) | .02 | 91 (1.0) | 24 (2.9) | .01 |

| Drug use | 145 (0.6) | 28 (1.1) | .02 | 64 (0.7) | 11 (1.3) | .047 |

| Psychoses | 580 (2.5) | 92 (3.5) | .01 | 249 (2.7) | 32 (3.9) | .04 |

| Preoperative medications, No. (%) | ||||||

| Muscle relaxants | 1175 (5.1) | 264 (1.1) | .01 | 426 (4.6) | 79 (9.6) | .01 |

| Benzodiazepine | 2086 (9.0) | 388 (14.9) | .02 | 1047 (11.2) | 175 (21.3) | .01 |

| Antipsychotics | 141 (0.6) | 32 (1.2) | .01 | 70 (0.7) | 10 (1.2) | .15 |

| Discharge location, No. (%) | ||||||

| Home | 17 500 (90.0) | 1951 (1.0) | .02 | 6530 (91.9) | 578 (8.1) | .03 |

| Home with home health | 3490 (90.1) | 382 (9.9) | 1880 (93.0) | 142 (7.0) | ||

| Facility | 2091 (88.2) | 279 (11.8) | 933 (90.2) | 101 (9.8) | ||

| Length of stay, mean (SD), d | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.3 (2.4) | .01 | 5.8 (2.7) | 6.1 (2.8) | .01 |

Abbreviation: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Persistent opioid use is defined as an opioid-naive patient who fills an opioid prescription within 14 days after surgery and refills a prescription within 90 to 180 days after surgery.

Table 2. Risk Factors for New Persistent Opioid Use 90 to 180 Days After Cardiac Surgery.

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Surgery type | ||

| CABG | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Valve surgery | 0.78 (0.70-0.86) | <.001 |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | <.001 |

| Men | 0.87 (0.79-0.97) | .01 |

| White | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | .49 |

| Year of surgery | 0.96 (0.95-0.98) | <.001 |

| Education | ||

| <High school diploma | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| High school diploma | 1.37 (0.70-2.71) | .36 |

| <Bachelor’s degree | 1.32 (0.67-2.60) | .43 |

| More bachelor’s degree | 1.10 (0.55-2.19) | .78 |

| Income, $ | ||

| <40 000 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 40 000-49 000 | 0.98 (0.84-1.16) | .87 |

| 50 000-59 000 | 1.00 (0.86-1.18) | .93 |

| 60 000-74 000 | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | .43 |

| 75 000-99 000 | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) | .14 |

| >100 000 | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | .04 |

| Preoperative comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | .30 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.17 (1.06-1.30) | .002 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 0.91 (0.77-1.07) | .29 |

| Diabetes | 1.27 (1.15-1.40) | <.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1.31 (1.19-1.45) | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.57 (1.25-1.96) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.11 (1.01-1.23) | .03 |

| Kidney failure | 1.17 (1.00-1.37) | .048 |

| Liver disease | 1.29 (1.02-1.64) | .03 |

| Obesity | 1.08 (0.96-1.21) | .18 |

| Weight loss | 1.14 (0.86-1.51) | .36 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 0.97 (0.68-1.39) | .87 |

| Paralysis | 0.92 (0.56-1.48) | .72 |

| Neurological disorders | 1.10 (0.90-1.35) | .32 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) | .50 |

| Deficiency anemias | 1.02 (0.90-1.15) | .70 |

| Psychoses | 0.99 (0.77-1.26) | .95 |

| Depression | 1.07 (0.91-1.25) | .41 |

| Chronic pain | 2.73 (2.10-3.56) | <.001 |

| Alcoholism | 1.56 (1.23-2.00) | <.001 |

| Drug use | 1.06 (0.70-1.60) | .78 |

| Psychoses | 1.00 (0.78-1.27) | .95 |

| Preoperative medications | ||

| Muscle relaxants | 1.74 (1.51-2.02) | <.001 |

| Benzodiazepine | 1.71 (1.52-1.91) | <.001 |

| Antipsychotics | 0.83 (0.53-1.32) | .44 |

| Discharge status | ||

| Home | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Home with home health | 0.99 (0.86-1.14) | .91 |

| Facility | 1.35 (1.12-1.56) | <.001 |

| Length of stay | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | .002 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; NA, not applicable.

Results

Patients

Of 131 620 patients who underwent cardiothoracic surgery during the study period, 35 817 patients were eligible to be included in the study. We identified 25 673 patients who underwent CABG (71.7%) and 10 144 who underwent a valve surgery procedure (28.3%). Table 1 presents the patient characteristics and demographic data of CABG and heart valve surgery patients stratified by new persistent opioid use. Cardiac surgery patients with new persistent opioid use were more likely women, had less advanced degrees, and a greater burden of preoperative comorbidities. Additionally, patients with persistent opioid use had increased proportions of chronic pain, depression, alcoholism, drug use, and preoperative benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and antipsychotic medications.

Postoperative Opioid Prescriptions

Most opioid-naive cardiothoracic surgery patients filled an opioid prescription within the first 14 days after surgery. Among all cardiac surgery patients in the Optum database from 2004 to 2016 who had Optum prescription data and at least 30 days of follow up, we found that 15 558 CABG patients (60.6%) and 5447 valve surgery patients (53.7%; P < .001) filled an opioid prescription within 14 days after the surgery.

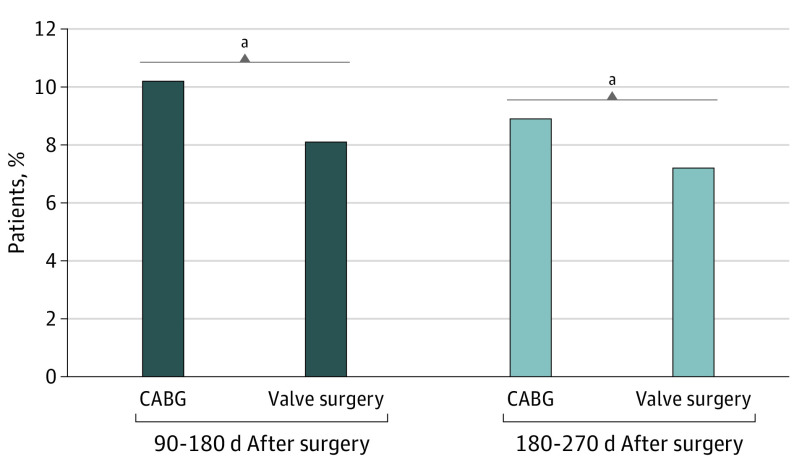

New Persistent Opioid Use After Cardiac Surgery

We determined the proportion of patients who had new persistent opioid use at 90 to 180 days and 180 to 270 days after the index cardiac procedure (Figure 2). Overall, 3430 cardiac surgery patients (9.6%) had new persistent opioid use within 90 to 180 days. Figure 2 presents the proportions of new persistent opioid use for each surgery type and we found that 2609 CABG patients (10.2%) and 821 valve surgery patients (8.1%) continued to fill an opioid prescription within 90 to 180 days postoperatively (P < .001) and 2285 CABG (8.9%) and 730 valve surgery patients (7.2%) continued to fill an opioid prescription within 180 to 270 days postoperatively (P < .001).

Figure 2. Proportion of Patients With Persistent Opioid Use After Cardiac Surgery.

Persistent opioid use is defined as a patient filling an opioid prescription within 90 to 180 days after surgery. Also included is the proportion of patients that have persistent opioid use at 180 to 280 days after surgery. On univariate analysis, the type of cardiac surgery was statistically significant during both periods. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting.

aP < .001.

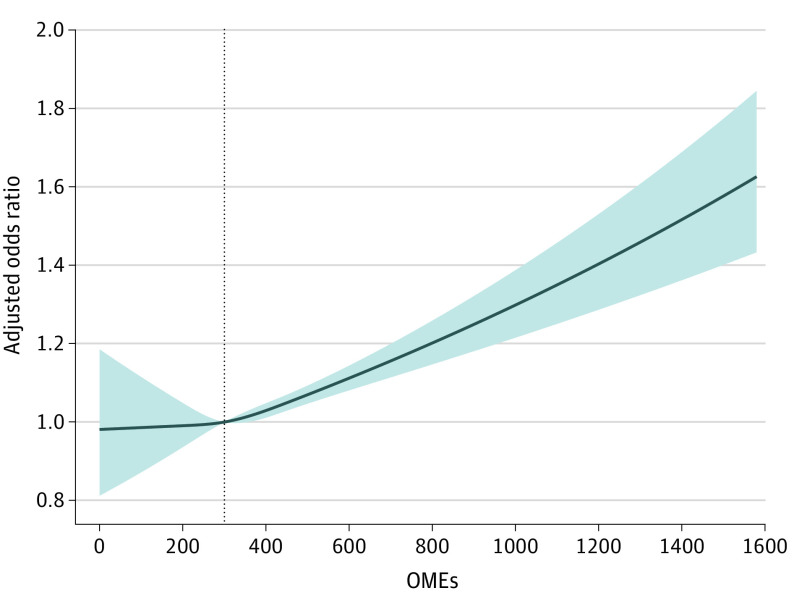

Risk Factors for Opioid Dependence After Cardiac Surgery

We found a direct, nonlinear association of the amount of opioids (total OME) from the first prescription at discharge with the likelihood of new persistent opioid use 90 to 180 days after surgery (Figure 3). The median OME at discharge of 300 mg (interquartile range, 200-450 mg) was used as a reference. Patients who were prescribed more than 300 mg at discharge had a significantly increased risk for developing persistent opioid use than compared with patients prescribed fewer OMEs. Furthermore, we found that patients who underwent valve surgery (odds ratio [OR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.86; P < .001) compared with CABG were less likely to become persistent opioid users after surgery. Additionally, those who were older (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < .001), men (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97; P < .01), and had a yearly income greater than $100 000 (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99; P = .04) were less likely to become persistent users. However, patients with congestive heart failure (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30; P = .002), chronic lung disease (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.19-1.45; P < .001), diabetes (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.40; P < .001), kidney failure (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.00-1.37; P = .048), liver disease (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.02-1.64; P = .03), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.25-1.96; P < .001) had an increased risk for persistent use. Additionally, patients with chronic pain (OR, 2.73; 95% CI, 2.10-3.56; P < .001), alcoholism (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.23-2.00; P < .001), use of preoperative muscle relaxants (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.51-2.02; P < .001), and use of preoperative benzodiazepines (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.52-1.91; P < .001), increased length of stay (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P < .002), and discharge to a facility compared with home (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.12-1.56; P < .001) had an increased risk for persistent opioid use.

Figure 3. Association of the Oral Morphine Equivalents (OMEs) of the First Prescription After Cardiac Surgery and the Likelihood of Developing New Persistent Opioid Use.

An OME of 300 mg (the median OME prescribed) was used as the reference point. Patients who were prescribed more than 300-mg OME (approximately 40 tablets of oxycodone, 5 mg) had an increased likelihood of developing persistent opioid use 90 days after surgery. Patients who were prescribed between 5- to 299-mg OME had the same odds of becoming persistent users. Oral morphine equivalents are defined as the total number of opioid tablets dispensed multiplied by the dosage and the morphine conversion factor. Persistent opioid use is defined as a patient filling an opioid prescription within 90 to 180 days after surgery. The shaded area of the figure represents the 95% CI of the odds ratio interval.

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine if the results of this study would apply to low-risk patients after cardiac surgery, we calculated the incidence of persistent opioid use after cardiac surgery and excluded patients at high risk for new persistent opioid use. We excluded patients who had preoperative use of benzodiazepines (4517 [12.6%]), muscle relaxants (1691 [4.7%]), alcoholism (659 [1.8%]), chronic pain (476 [1.3%]), drug use (155 [0.43%]), and those discharged to a facility (3402 [9.5%]) after surgery. Among the residual low-risk cohort (26 716 [74.6%]), we found a similar overall incidence of opioid dependence within 90 to 180 days after discharge at for 2191 (8.2%) (8.9% for CABG and 6.5% for valve patients) (eTable and eFigure in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this large study cohort of privately managed health insurance patients, we found that opioids are extensively used after cardiac surgery and that new persistent opioid use within 90 to 180 days from surgery is a substantial concern, occurring in approximately 1 in 10 patients (CABG, 10.2%; valve surgery, 8.1%). We determined that the initial amount of opioids prescribed to a patient at discharge is associated with the likelihood of developing persistent use. We found that prescriptions of approximately 300-mg OMEs or more at discharge significantly increases the risk that a patient becomes a persistent user after surgery. Additionally, we found several other factors of new opioid dependence. Patients who underwent CABG; those who were younger, female, with preoperative chronic pain, alcoholism, and taking preoperative benzodiazepines or muscle relaxants; and those discharged to a facility instead of home were all associated with increased risk of persistent opioid use.

In this study, prolonged opioid use was found in 10.2% of CABG patients and 8.1% of heart valve surgeries. We defined new persistent opioid use as an opioid-naive patient filling an opioid prescription within 14 days after surgery and filling another opioid prescription within 90 to 180 days after surgery, similarly to other studies that have investigated this topic for other surgeries.7,9,16 Using similar methods, Clarke et al9 performed a population-based cohort study from 2008 to 2010 among patients in Ontario, Canada, and found that new persistent opioid use 90 to 180 days after surgery occurred in approximately 3.3% of CABG patients. Plausible reasons for the lower proportion of persistent opioid use may be that the previous study was completed before the opioid crisis reached peak intensity or intrinsic differences in practice and prescribing patterns between Canada and the US. Recently, Brescia et al16 performed an analysis of persistent opioid use after cardiac surgery in the Medicare population. In this elderly population, they found similar rates of new persistent opioid use after heart surgery, transcatheter valve, esophagectomy, or lung resection. Our study confirms these findings while focusing on key index open cardiac surgical cases using a database that includes a younger patient cohort that is geographically diverse and does not include patients who may be undergoing percutaneous surgeries or chemotherapy. The mean age of patients in our study was approximately 10 years younger and the incidence of opioid dependency persists even when patients with high-risk features are excluded, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously shown in this population.

In this study, we have demonstrated a direct association between the amount of opioids (total OMEs) prescribed at discharge and the likelihood of persistent opioid use 90 days after cardiac surgery. We found that patients who were prescribed more than approximately 300-mg OME at discharge (approximately 40 tablets of oxycodone, 5 mg) had a significantly increased likelihood of persistent use. This reference of 300-mg OME was also the median OME prescribed at discharge, indicating that 50% of all patients who received opioids after cardiac surgery obtained an amount that is associated with increased risk for persistent use after 90 days. In the study by Brummett et al7 that examined the incidence of new persistent opioid use after minor and major general surgery procedures using the Optum database, it was also found that OMEs greater than 300 mg were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of opioid dependence after 90 days from general surgery procedures. Studies have demonstrated that the more opioids a patient is prescribed, the more opioids the patient consumes, regardless of postoperative pain.10,11,12,13,17 In a study by Howard et al,13 the investigators studied 2392 patients from a clinical registry in Michigan who underwent general surgery procedures and found that the more opioid pills prescribed (increased OME) at discharge, the more patients reported consuming, even after adjusting for procedure type, age, and comorbidities. This provides a plausible mechanism for why patients in our study who were prescribed increased amounts of opioids at discharge had a higher risk for persistent opioid use. Concerningly, it has been shown that increased opioid doses are associated with increased risk for overdose and death.17 Taken together, these results, in addition to our own, support decreasing opioid dosages at discharge (lower OMEs) and using alternative modalities, such as enhanced recovery after surgery protocols, to prevent overprescribing, decrease the risk for persistent opioid use, and prevent opioid overdose.

In addition to the amount of opioids prescribed at discharge, we found several other risk factors for persistent opioid use among cardiac surgery patients. Patients who are younger, with increased preoperative comorbidities (eg, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, liver disease, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis), preoperative chronic pain and alcoholism, taking preoperative benzodiazepines and muscle relaxants, and those discharged to a facility vs home were all at increased risk for persistent opioid use after 90 days. Identifying these high-risk patients before surgery who may be at increased risk for persistent opioid use is critical. However, when we performed the analysis after excluding these high-risk patients, we found the incidence of persistent opioid use was 8.2%. This illustrates the multifactorial causes of the opioid crisis and that persistent opioid use after surgery may be associated with other unmeasurable factors, such as opioid marketing and cultural factors.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this is an observational study that used an administrative database and is subject to coding errors and misclassification. Second, our study consisted of adults with private insurance or Medicare-managed coverage and may not be generalizable to patients younger than 18 years or patients without private insurance. While we attempted to exclude patients who had additional anesthesia and surgery, it is not possible to know with certainty if an opioid prescription that was prescribed within 90 to 180 days after surgery is because of the prolonged opioid use or an acute pain issue. However, not every patient with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code with new acute pain is prescribed opioids. We also were unable to investigate commonly used analgesic medications, such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or aspirin, as they are over the counter and not present in the Optum insurance prescription database. While we analyzed the opioid prescriptions that patients received through a pharmacy, we do not have data that the patient used all the opioids prescribed. Additionally, it is likely that psychiatric illnesses, such as alcoholism and others that may be risk factors for persistent opioid use, are underreported in electronic medical records and administrative databases. We did not explore if the indication of surgery is associated with persistent opioid use and there are no CPT or ICD codes to determine the association with the type of incision (sternotomy vs thoracotomy). Lastly, it is possible that this study may underestimate the risk of persistent opioid use, as patients may have acquired opioids by alternative sources not captured within this database.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that approximately 1 of 10 opioid-naive cardiac surgery patients will continue to use opioids 90 days after surgery. However, the most notable finding from our study is that patients who were prescribed approximately 300-mg OMEs (or approximately 40 tablets of oxycodone, 5 mg) at discharge were at increased risk for developing new persistent opioid use with 90 to 180 days from discharge. Cardiothoracic surgeons, cardiologists, primary care clinicians, and advanced practitioners should all enact evidence-based protocols to identify high-risk patients for persistent use and minimize opioid prescriptions postoperatively with multimodal analgesia techniques.

eTable. Risk Factors for New Persistent Opioid Use 90-180 Days After Cardiac Surgery in Low Risk Patients for New Persistent Opioid Use

eFigure. Association of the Oral Morphine Equivalents of the First Prescription after Cardiac Surgery and the Likelihood of Developing New Persistent Opioid Use Among Low Risk Patients for New Persistent Opioid Use

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER. Accessed December 11, 2019. https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

- 2.Leider HL, Dhaliwal J, Davis EJ, Kulakodlu M, Buikema AR. Healthcare costs and nonadherence among chronic opioid users. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):32-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-430. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):1979-1986. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brescia AA, Waljee JF, Hu HM, et al. Impact of prescribing on new persistent opioid use after cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108(4):1107-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirji SA, Landino S, Cote C, et al. Chronic opioid use after coronary bypass surgery. J Card Surg. 2019;34(2):67-73. doi: 10.1111/jocs.13981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066-1071. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, Bullard KJ, Hopfer CJ, Binswanger IA. Opioid use and storage patterns by patients after hospital discharge following surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. 2011;185(2):551-555. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):e184234. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B, Evans D, Faris P, Dean S, Quan H. Risk adjustment performance of Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidities in ICD-9 and ICD-10 administrative databases. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brescia AA, Harrington CA, Mazurek AA, et al. Factors associated with new persistent opioid usage after lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(2):363-368. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Risk Factors for New Persistent Opioid Use 90-180 Days After Cardiac Surgery in Low Risk Patients for New Persistent Opioid Use

eFigure. Association of the Oral Morphine Equivalents of the First Prescription after Cardiac Surgery and the Likelihood of Developing New Persistent Opioid Use Among Low Risk Patients for New Persistent Opioid Use