Abstract

Background: We conducted a randomized controlled trial of EpxDiabetes, a novel digital health intervention as an adjunct therapy to reduce HbA1c and fasting blood glucose (FBG) among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In addition, we examined the effect of social determinants of health on our system.

Methods: Sixty-five (n = 65) patients were randomized at a primary care clinic. Self-reported FBG data were collected by EpxDiabetes automated phone calls or text messages. Only intervention group responses were shared with providers, facilitating follow-up and bidirectional communication. ΔHbA1c and ΔFBG were analyzed after 6 months.

Results: There was an absolute HbA1c reduction of 0.69% in the intervention group (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.41 to 0.02) and an absolute reduction of 0.03% in the control group (95% CI, −0.88 to 0.82). For those with baseline HbA1c >8%, HbA1c decreased significantly by 1.17% in the intervention group (95% CI, −1.90 to −0.44), and decreased by 0.02% in the control group (95% CI, −0.99 to 0.94). FBG decreased in the intervention group by 21.6 mg/dL (95% CI, −37.56 to −5.639), and increased 13.0 mg/dL in the control group (95% CI, −47.67 to 73.69). Engagement (proportion responding to ≥25% of texts or calls over 4 weeks) was 58% for the intervention group (95% CI, 0.373–0.627) and 48% for the control group (95% CI, 0.296–0.621). Smoking, number of comorbidities, and response rate were significant predictors of ΔHbA1c.

Conclusions: EpxDiabetes helps to reduce HbA1c in patients with uncontrolled T2DM and fosters patient–provider communication; it has definite merit as an adjunct therapy in diabetes management. Future work will focus on improving the acceptability of the system and implementation on a larger scale trial.

Keywords: telemedicine, diabetes, glycemic control, self-monitoring, digital health, e-health

Introduction

Diabetes is estimated to affect 30.3 million people (9.4% of the population) in the United States.1 Long-term glycemic control can decrease the incidence of organ damage from microvascular and macrovascular complications.2 The 2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimates that 30% of adults with diabetes have not met target HbA1c levels.3 In addition, 63.9% of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) do not meet American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended self-monitoring frequencies.4 Generating new methods to promote self-blood glucose measurements and facilitate patient–provider assessment has the potential to positively impact blood glucose control in large populations.

Previous studies indicate that telemedicine interventions can improve patient outcomes by facilitating remote glycemic monitoring, patient–provider communication, and glycemic control.5–9 However, multiple factors can influence the success of telemedicine interventions. The use of specialized telemedicine devices shows high attrition rates due to user frustration and high device costs.10,11 Advancing age, low socioeconomic status, and low health literacy impair the ability to use new technology effectively, resulting in overall lower usage.12–18 Telemedicine modalities using short messaging service (SMS) and phone calls are particularly appealing due to their ubiquity and standard integration into cellular phones, with findings that 92% of those making less than $30,000 own a cellular phone.10

EpxDiabetes is a SMS and phone call-based intervention that allows for bidirectional patient–provider communication. This closed-loop communication is important for achieving glycemic control since many patients do not take action in response to high or low readings19 and may experience anxiety from uncontrolled blood glucose readings and infrequent physician feedback.20 Barriers faced by other telemedicine interventions include response burden for patients and effort burden for physicians to provide real-time feedback.21 EpxDiabetes reduces these particular barriers by utilizing a simple, widely used system, and triaging patient data to prioritize physician action. Upon detecting a dysglycemic event or trend from self-reported fasting blood glucose (FBG), EpxDiabetes prompts the patient's provider to follow-up with the patient, allowing for concerted provider detection and early intervention.

We previously demonstrated the real-world effectiveness of EpxDiabetes in lowering FBG and HbA1c in a community health care system implementation.5 We have now conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to assess the efficacy of EpxDiabetes in lowering FBG and HbA1c in patients with poor glycemic control (HbA1c > 7%), comparing the intervention group to our practice standard of care. In addition, we assessed the impact of social determinants of health on the efficacy of our system.

Methods

Participant Selection, Recruitment, and Enrollment

The IRB-approved 6-month RCT was conducted at a primary care clinic in St. Louis, Missouri. Standard of care consists of quarterly clinic visits and monthly provider calls from pharmacists to assess and modify patients' diabetes management plan.

We queried the clinic's electronic medical record (EMR) using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (250.x) and medication lists for patients with noninsulin-dependent T2DM seen within 18 months before the trial start date. Eligible patients were older than the age of 18 years and had a most recent HbA1c value of >7%. Patients were excluded from the trial if they did not have access to a mobile phone or landline, participated in previous implementations of EpxDiabetes, or were not currently monitored by the pharmacists.

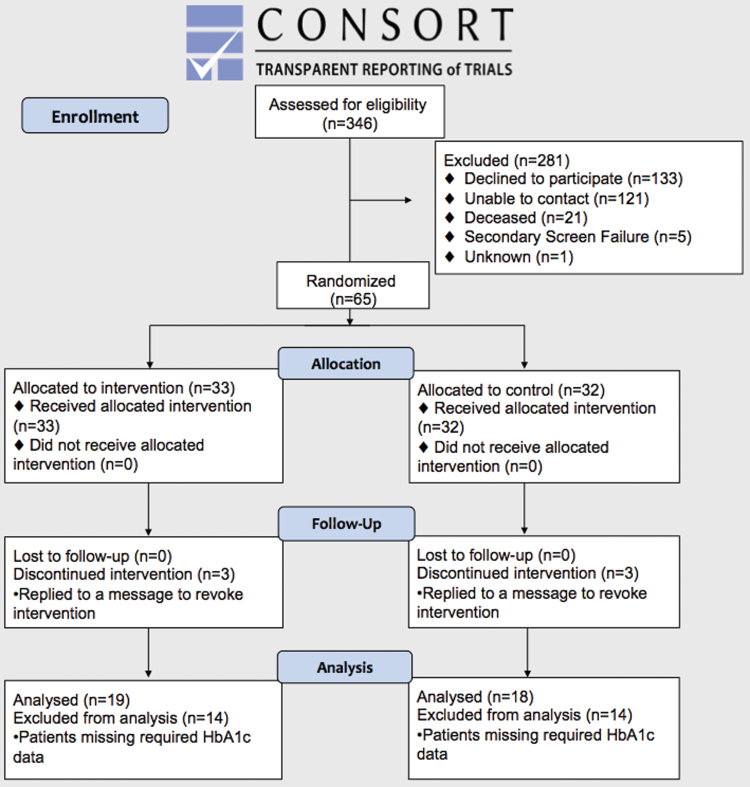

Subjects meeting selection criteria were consented and recruited via phone from March to June 2016 on a rolling basis by independent research staff. Three hundred twenty-five (325) out of 346 eligible patients met enrollment criteria, 203 were successfully contacted, and 65 consented. Participants were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to intervention and control arms using simple randomization via the integrated function within the epx.wustl.edu platform. For each patient, a random IEEE754 float point value in the interval of [0, 1] was generated via the “Math.random” function from JavaScript. If the value was >0.5, then the patient was added to the control group; otherwise, the patient was added to the intervention group. Simple randomization assigned 33 subjects to the intervention group, and 32 subjects to the control group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. Color images are available online.

Study Design and Intervention

EpxDiabetes is based on an existing telemedicine platform, Epharmix, and customized for diabetes care as outlined in Peters et al.5 by allowing for collection of FBG. Being mindful of limited health literacy requiring interventions with simple, easy-to-read instructions, all EpxDiabetes messages are designed at a fourth grade level as determined by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula and calculated on the Readable.io website. Text messages and phone calls were provided free of charge (excluding standard messaging rates) to patients on any network to further promote accessibility among low socioeconomic populations.

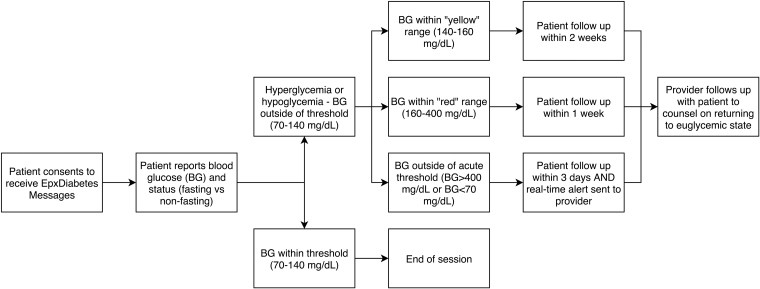

Patients self-report FBG values by responding to automated phone calls or SMS messages (Fig. 2). FBG values >400 or <70 mg/dL trigger an automated alert via text or phone call to the provider for a possible acute event, and the platform issues an automated instruction directly to patients to contact their providers and/or call 911 in an emergency. The algorithm recognizes hyperglycemic trends and notifies providers if bimonthly average FBG exceeds 160 mg/dL. The Smart Scheduler modifies message frequency based on FBG to minimize message fatigue; patients reporting euglycemia receive messages less frequently.

Fig. 2.

EpxDiabetes intervention design and Alert protocol. Adapted from Peters et al.,5 a concomitant quality improvement trial using EpxDiabetes.

The intervention group received messages an average of three times per week (twice a week to three times a day), depending on FBG stability. The control group received messages three times during the first week to establish a FBG baseline and once weekly thereafter without modifications from the Smart Scheduler. The control group did not receive any provider-initiated follow-up based on the self-reported FBG data, however, they were instructed to call their provider or 911 if severely dysglycemic and continue to receive standard of care.

Data Gathering and Analysis

Demographic data were obtained from patients at the time of enrollment. Group differences were evaluated with a two-tailed t-test (α = 0.05).

Pretrial, our primary outcomes were change in HbA1c and change in FBG. Secondary outcomes were response rate and engagement rate. Details on how each of these were calculated can be found below.

We included only those patients who had obtained a baseline HbA1c (within 3 months before enrolment into the trial) and a posttrial HbA1c (within 4–8 months after enrolment into the trial) in our analysis for HbA1c to evaluate a direct glycemic effects of SMS intervention. HbA1c values were extracted from the EMR 6 months after trial start date for each patient. ΔHbA1c from baseline to posttrial was calculated. An intention to treat analysis was performed for patients who did not respond through 6 months, but who did have HbA1c measurements. A subgroup analysis was performed for patients with baseline HbA1c >8%.

Baseline FBG for each patient was calculated by averaging the first three patient-reported FBG values. To account for the variable weekly message frequency, monthly FBG was determined for each patient by averaging four consecutive weekly FBG averages. The group average monthly ΔFBG was calculated for the two groups.

Deidentified patient engagement data and response rates were obtained from the Epharmix database. Patient monthly engagement rate was defined as the proportion of patients responding to at least 25% of texts or calls over 4 weeks. Average group monthly engagement was calculated. Patient response rate was the proportion of sent SMS messages or phone calls responded to.

Multiple linear regressions predicting ΔHbA1c and ΔFBG after 6 months was found using backward elimination and interpreted using adjusted R2. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (2016; Microsoft, Redmond, WA), PRISM (2016; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), and SPSS (2016; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

African Americans represent the majority in both groups. The median income was $14,440 for the intervention group and $12,600 for the control group. The demographic differences between intervention and control groups were nonsignificant (p > 0.05) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the distribution of specific comorbidities, other than lung disease, nor in number of comorbidities between the intervention group and control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| INTERVENTION GROUP | CONTROL GROUP | |

|---|---|---|

| 33 | 32 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 (37.5%) | 8 (25%) |

| Female | 20 (62.5%) | 24 (75%) |

| Age | ||

| Average ± SEM | 54.6 ± 1.82 | 55.34 ± 1.94 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 6 (18%) | 2 (7%) |

| African American | 27 (82%) | 29 (93%) |

| Disability status | ||

| Disableda | 19 (58%) | 20 (63%) |

| Nondisabled | 14 (42%) | 12 (37%) |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Grade school | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Some high school | 4 (12%) | 10 (31%) |

| High school graduate | 11 (33%) | 10 (31%) |

| Some college | 13 (39%) | 7 (22%) |

| College graduate or beyond | 4 (12%) | 4 (13%) |

| Income | ||

| Mean ± SEM | $18,993 ± 3,843 | $16,525 ± 2,125 |

| Median | $14,440 | $12,600 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 26 (79%) | 25 (78%) |

| Lung diseaseb | 6 (18%) | 14 (44%) |

| Heart disease | 2 (6%) | 6 (19%) |

| Thyroid disease | 2 (6%) | 5 (16%) |

| Neurological disease | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) |

| Cancer | 3 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Other | 9 (27%) | 10 (31%) |

| No. of comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 5 (15%) | 4 (13%) |

| 1 | 15 (45%) | 11 (34%) |

| 2 | 5 (15%) | 7 (21%) |

| 3 | 6 (19%) | 4 (13%) |

| 4 | 1 (3%) | 4 (13%) |

| 5+ | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

Receiving disability pay.

p < 0.05 between groups.

SEM, standard error of the mean.

HbA1C and FBG Analysis

Pretrial and posttrial HbA1c were available for 19 patients in the intervention group and 18 patients in the control group due to missing the appointment within 4–8 months after enrollment into the trial; 29 out of 37 patients had a baseline HbA1c >8%. On average, patients obtained their posttrial HbA1c values 6 months after start of messages (181 days for intervention, 186 days for control). Patients were enrolled with an indefinite endpoint, outcomes were assessed at 6 months after enrolment.

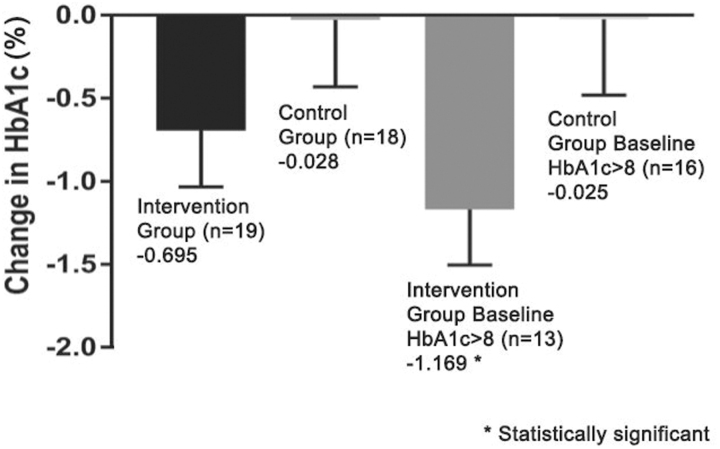

Average HbA1c in the intervention group was 9.80% (standard error of the mean [SEM] = 0.45%, n = 19) at baseline and decreased to 9.11% (ΔHbA1c = −0.69%, SEM = 0.34%, p = 0.055) posttrial. Average HbA1c in the control group was 9.23% (SEM = 0.32, n = 18) at baseline and barely decreased posttrial to 9.20% (ΔHbA1c = −0.03%, SEM = 0.40, p = 0.946). Baseline HbA1c was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.31).

Patients in the intervention group with baseline HbA1c >8% (n = 13) had a statistically significant decrease in HbA1c from 10.92% at baseline to 9.75% posttrial (ΔHbA1c = −1.17%, SEM = 0.33, p = 0.004), while those in the control group with baseline HbA1c >8% (n = 16) had a nonsignificant decrease from 9.46% at baseline to 9.44% posttrial (ΔHbA1c = −0.02%, SEM = 0.46, p = 0.957) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of intervention and control group ΔHbA1c after 6 months.

Patient-reported FBG was retrieved from the Epharmix system and only patients who responded throughout 6 months were analyzed. Average FBG in the intervention group was 172.5 mg/dL (SEM = 12.3 mg/dL, n = 17) at baseline and decreased to 150.9 mg/dL (ΔFBG −21.6 mg/dL, SEM = 7.5 mg/dL, p = 0.01) posttrial. Average FBG in the control group was 191.1 mg/dL (SEM = 17.1 mg/dL, n = 16) at baseline and increased posttrial to 204.1 mg/dL (ΔFBG +13.0 mg/dL, SEM = 28.5 mg/dL, p = 0.65). Baseline FBG was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.38). These results are consistent with our HbA1c changes from baseline in the intervention group.

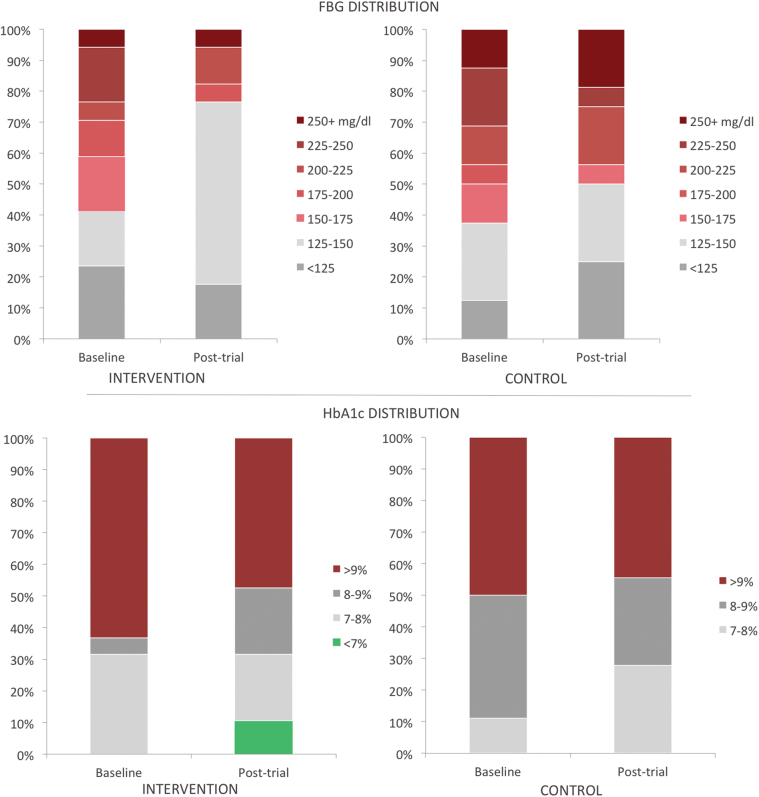

At baseline, all patients in the study had HbA1c >7%. Posttrial, 11% of patients in the intervention group had HbA1c <7%, while none did in the control group (Fig. 4). In the intervention group, 63% of patients had HbA1c >9%, which decreased to 47% posttrial (Fig. 4). Changes of this magnitude were not seen in the control group (50–44% with HbA1c >9%). Correspondingly, at baseline, 63% of the intervention group had FBG above 150 mg/dL, which reduced to 32% posttrial (Fig. 4). The control group had 67% with FBG above 150 mg/dL at baseline, which decreased slightly to 56% posttrial (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of the intervention and control groups across HbA1c values and FBG values from baseline to posttrial. FBG, fasting blood glucose. Color images are available online.

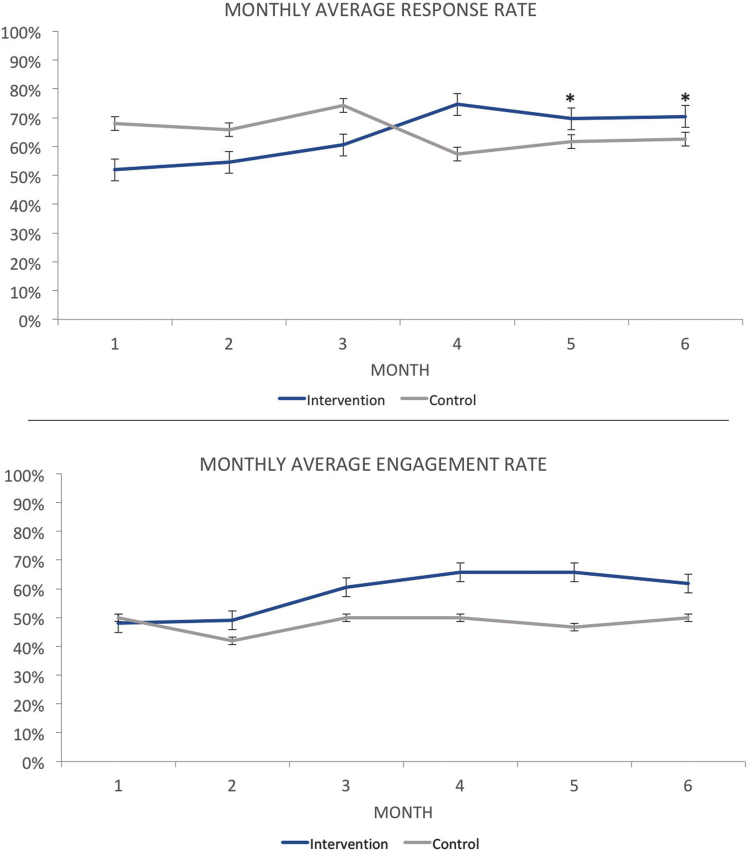

Response Rate

Response rate was defined as the absolute proportion of total text messages or calls responded to. The overall average response rate for the entire duration of the trial was 64.9% for the control group and 63.6% for the intervention group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The average response rates and average engagement rates for each month of intervention. Standard error bars are displayed. *Response rates were significantly different during months 5 and 6. Color images are available online.

Engagement Rate

Engagement rate was defined as the proportion of participants who responded to at least 25% of SMS or phone calls over 4 weeks. The average engagement rate was 48% for the control group (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.296–0.621) and 58% for the intervention group (95% CI, 0.373–0.627) (Fig. 5).

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis: Demographic Factors Predicting Changes in ΔHbA1C

Multiple linear regressions were calculated to predict ΔHbA1c at the end of the 6-month trial based on baseline ΔHbA1c, education, smoking status, income, age, number of comorbidities, and response rate (Table 2). Significant predictors of intervention ΔHbA1c were smoking status, number of comorbidities, and response rate. In contrast, the only significant predictor of control ΔHbA1c was baseline HbA1c. Significant predictors of intervention ΔFBG were baseline FBG and smoking status. There were no significant predictors of control ΔFBG.

Table 2.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors Predicting Changes in HbA1c

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLE | INTERVENTION ΔHbA1C |

CONTROL ΔHbA1C |

INTERVENTION FBG |

CONTROL FBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COEFFICIENT | COEFFICIENT | COEFFICIENT | COEFFICIENT | |

| Baseline HbA1c | −0.756a | — | — | |

| Baseline FBG | — | — | −0.265a | −0.378 |

| Education | −0.649 | |||

| Smoking status | −0.929a | −28.920a | ||

| Income (thousands) | 0.004 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | −0.066 | |||

| No. of comorbidities | −0.635a | |||

| Response rate | −2.595a | 31.205 | 245.878 | |

| Constant | 2.551 | 9.918 | 24.883 | −113.875 |

| R2adj | 0.669 | 0.302 | 0.598 | 0.248 |

| F-ratio | 7.062a | 2.512 | 5.459a | 2.207 |

| n | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 |

A higher value for smoking status indicates less smoking.

p < 0.05.

FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Discussion

As the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, it is essential to develop and implement cost-effective therapeutic strategies to achieve glycemic control. Current methods are less effective for the 30.9–33.4% of adults in the United States who are above target HbA1c levels.3,22 Our study shows a statistically significant HbA1c reduction of 1.17% for patients in the intervention group with baseline HbA1c >8% by using SMS and phone-based interventions that allow for bidirectional patient–provider communication. This change in HbA1c was supported by a significant decrease in self-reported average FBG, half of patients with baseline FBG >150 mg/dL getting below 150 mg/dL posttrial, and a 11% increase in the amount of patients with well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c <7%) in the intervention group. This is clinically significant because standard therapies for T2DM, which include oral antihyperglycemic agents, are known to lower HbA1c by 0.5–1.25%.23 Our nonpharmacologic, low-cost, and low-risk intervention complements standard pharmacologic therapies by further reducing HbA1c by a comparable amount. While it has been demonstrated that the lowest risk of complications is achieved when patients can lower their HbA1c to <6%, it is also clear that any reduction from baseline HbA1c can be beneficial in risk reduction.24

Smoking status was a significant predictor of HbA1c and FBG changes. Those who never smoked saw greater decreases in HbA1c and FBG than former and current smokers. These findings correlate with previous studies demonstrating that smoking exacerbates insulin resistance and the micro- and macrovascular complications of T2DM.25 Response rate was a significant predictor of HbA1c in the intervention group, but not in the control group. This difference is likely due to the greater messaging frequency and the bidirectional communication between patients and providers experienced by the intervention group. Greater response rate to the intervention was associated with decreases in HbA1c.

The engagement rate was high for both the intervention group (58%) and control group (48%). While definitions of engagement vary, in similar studies, the proportion of people ever using an intervention ranged from 28% to 53%.26,27 Interestingly, the intervention group, which received more messages relative to the control group, showed higher response and engagement rates after 6 months of intervention. However, the response rate was a nonsignificant predictor of changes in FBG. Higher response rates were correlated with increases in FBG. This may seem to contradict the effectiveness of EpxDiabetes, but patients with FBG instability receive additional messages by platform design, and higher FBG may trigger increased engagement with the system due to concerns about glycemic control. Patients are more likely to enroll in and engage with telemedicine interventions when it is perceived to be beneficial.28–30 Patients are less likely to consider an intervention beneficial when their blood glucose seems to be in control.30,31

At baseline, the intervention group had a lower response rate. This may reflect the heavier message burden before the Smart Scheduler reduced the frequency of messages based on FBG stability. We believe that the bidirectional patient–provider communication the intervention group received encourages greater response and engagement rates compared to the control group without physician feedback. Macdonald et al.12 noted that diabetes telemedicine interventions allow for timely physician feedback, which increases patient perceptions of intervention usefulness, increasing usage, and engagement. Bidirectional communication can encourage engagement by increasing feelings of connectivity between patients and their health care providers.32,33 The higher engagement rate of the intervention group demonstrates the ability of EpxDiabetes to facilitate high engagement over long periods of time.

This intervention is a scalable and effective way of managing large numbers of patients and optimizing response to patient needs. In a previous study, EpxDiabetes was implemented as a single-arm quality improvement project across community clinics in St. Louis, Missouri, and managed 314 patients.5 EpxDiabetes gives actionable data to providers, enabling providers to follow-up and adjust treatment plans, and then to receive real-time feedback on those changes. We believe that this RCT is an appropriate ancillary study to follow up implementation of EpxDiabetes in a community setting in a more rigorous research setting.

Limitations to this study relate to sample size and scheduling for follow-up. As a result of low sample size, the trial had low power to detect significant changes in the intervention arm. In addition, a larger, more diverse study sample is needed to better understand differences in intervention effectiveness. Our study population reflected the patient population of our city, so generalizability would improve with a larger national or global trial.

We did not track the antihyperglycemic therapies or lifestyle interventions that the patient groups were given since it was assumed that they were on optimal medical therapy and care plan. In addition, since there were no differences in characteristics between the intervention and control groups at baseline, we are reasonably confident that any changes in FBG or HbA1c as a result of lifestyle or medication adherence changes can be attributed to aspects of our intervention. However, we acknowledge that it is important to identify which, if any, standard medical therapies or lifestyle interventions, such as diet or exercise, may have better complementarity to telemedicine. This will enable us to further tailor and individualize EpxDiabetes to patients on particular therapy plans. We will make every effort to include collection and analysis of these data in future studies.

Finally, not every patient was able to obtain HbA1c measurements that corresponded to an end-of-trial measurement, which results in a limitation to our sample size and a possible bias from self-selection of patients who prioritized management of their T2DM. We believe that this highlights the disparities in access to care and transportation barriers in our community, further emphasizing the need for a telemedicine tool in communities such as ours. In future studies, it will be beneficial to schedule both pretrial and posttrial measurements to ensure more patients meet the criteria for analysis. Finally, we recommend examining patient satisfaction to address barriers to engaging with the system.

Conclusion

EpxDiabetes is an effective telemedicine intervention that facilitates glycemic control for patients with T2DM, especially with baseline HbA1c >8%. It is low-cost, accessible, and facilitates high engagement for patients of different ages, health literacy, and socioeconomic levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Avik Som, Tonya An, and the entire Epharmix team for help with development and implementation of EpxDiabetes. We also thank Dr. Melvin Blanchard and Dr. Gregory Polites for their valuable input regarding the article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Epharmix, Inc. has provided in kind services (the text messages and phone call platform) for free. Additional research support from grants National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01HL094818 and Veterans Affairs (VA) merit award I01BX003648.

References

- 1. CDC diabetes. Available at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf (last accessed November30, 2017)

- 2. Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000 among U.S. adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: A preliminary report. Diabetes Care 2004;27:17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of Goals in U.S. Diabetes Care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1613–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vincze G, Barner JC, Lopez D. Factors associated with adherence to self-monitoring of blood glucose among persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2004;30:112–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peters RM, Lui M, Patel K, et al. Improving glycemic control with a standardized text-message and phone-based intervention: A community implementation. JMIR Diabetes 2017;2:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar VS, Wentzell KJ, Mikkelsen T, Pentland A, Laffel LM. The DAILY (Daily Automated Intensive Log for Youth) trial: A wireless, portable system to improve adherence and glycemic control in youth with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2004;6:445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, Goland R, et al. Glycemic control and health disparities in older ethnically diverse underserved adults with diabetes: Five-year results from the Informatics for Diabetes Education and Telemedicine (IDEATel) study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:274–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, et al. Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J 2009;181:37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shea S, Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus: 5 year results of the IDEATel study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:446–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mobile fact sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Technology. January 12, 2017. Available at www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile (last accessed November30, 2017)

- 11. Effects of telemedicine on the management of diabetes. HIMSS. November 1, 2015. Available at www.himss.org/effects-telemedicine-management-diabetes (last accessed November30, 2017)

- 12. Macdonald EM, Perrin BM, Kingsley MI. Enablers and barriers to using two-way information technology in the management of adults with diabetes: A descriptive systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:319–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaufman DR, Patel VL, Hilliman C, et al. Usability in the real world: Assessing medical information technologies in patients' homes. J Biomed Inform 2003;36:45–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaufman DR, Pevzner J, Hilliman C, et al. Redesigning a telehealth diabetes management program for a digital divide seniors population. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2006;18:223–234 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon ACR, Holleman F, Gude WT, et al. Safety and usability evaluation of a web-based insulin self-titration system for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Artif Intell Med 2013;59:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osborn CY, Mayberry LS, Wallston KA, Johnson KB, Elasy TA. Understanding patient portal use: Implications for medication management. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Kurz D, et al. Recruitment for an internet-based diabetes self-management program: Scientific and ethical implications. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Homko CJ, Deeb LC, Rohrbacher K, et al. Impact of a telemedicine system with automated reminders on outcomes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther 2012;14:624–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang J, Zgibor J, Matthews JT, Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika SM, Siminerio L. Self-monitoring of blood glucose is associated with problem-solving skills in hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Diabetes Educ 2012;38:207–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peel E, Parry O, Douglas M, Lawton J. Blood glucose self-monitoring in non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study of patients' perspectives. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54:183–188 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mulvaney SA, Ritterband LM, Bosslet L. Mobile intervention design in diabetes: Review and recommendations. Curr Diab Rep 2011;11:486–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015: Summary of revisions. Diabetes Care 2015;38(Supplement 1):S4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Sherifali D, Nerenberg K, Pullenayegum E, Cheng JE, Gernstein HC. The effect of oral antidiabetic agents on A1C levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1859–1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): Prospective observational study BMJ 2000;321:405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Chang SA. Smoking and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 2012;36:399–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, Laffel LM. Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS): E-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther 2009;11:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Faridi Z, Liberti L, Shuval K, Northrup V, Ali A, Katz DL. Evaluating the impact of mobile telephone technology on type 2 diabetic patients' self-management: The NICHE pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palmas W, Teresi J, Morin P, et al. Recruitment and enrollment of rural and urban medically underserved elderly into a randomized trial of telemedicine case management for diabetes care. Telemed J E Health 2006;12:601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turner J, Larsen M, Tarassenko L, Neil A, Farmer A. Implementation of telehealth support for patients with type 2 diabetes using insulin treatment: An exploratory study. Inform Prim Care 2009;17:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Kelders SM, Brandenburg BJ, Seydel ER. Factors influencing the use of a web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waki K, Aizawa K, Kato S, et al. DialBetics with a multimedia food recording tool, FoodLog: Smartphone-based self-management for type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:534–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaufman ND, Woodley PDP. Self-management support interventions that are clinically linked and technology enabled: Can they successfully prevent and treat diabetes? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011;5:798–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bull SS, Gaglio B, Garth Mckay H, Glasgow RE. Harnessing the potential of the Internet to promote chronic illness self-management: Diabetes as an example of how well we are doing. Chronic Illn 2005;1:143–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]